Abstract

In vivo mouse models have indicated that the intrinsic coagulation pathway, initiated by factor XII, contributes to thrombus formation in response to major vascular damage. Here, we show that fibrillar type I collagen provoked a dose-dependent shortening of the clotting time of human plasma via activation of factor XII. This activation was mediated by factor XII binding to collagen. Factor XII activation also contributed to the stimulating effect of collagen on thrombin generation in plasma, and increased the effect of platelets via glycoprotein VI activation. Furthermore, in flow-dependent thrombus formation under coagulant conditions, collagen promoted the appearance of phosphatidylserine-exposing platelets and the formation of fibrin. Defective glycoprotein VI signaling (with platelets deficient in LAT or phospholipase Cγ2) delayed and suppressed phosphatidylserine exposure and thrombus formation. Markedly, these processes were also suppressed by absence of factor XII or XI, whereas blocking of tissue factor/factor VIIa was of little effect. Together, these results point to a dual role of collagen in thrombus formation: stimulation of glycoprotein VI signaling via LAT and PLCγ2 to form procoagulant platelets; and activation of factor XII to stimulate thrombin generation and potentiate the formation of platelet-fibrin thrombi.

Introduction

Vascular injury leads to exposure of hemostatically active components, such as tissue factor and collagen, to the bloodstream. For a long time, it has been considered that exposed tissue factor is the main vascular activator of the coagulation cascade. In the extrinsic pathway of coagulation, de-encrypted tissue factor complexes with circulating factor (F)VII(a), which activates a multistep cascade of serine proteases to form thrombin and fibrin.1 The exposed collagen is thought to function as a substrate for the adhesion and activation of platelets via the glycoprotein VI (GPVI) receptor, which evokes an important signal transduction pathway in platelets.2

Independently of tissue factor, the second intrinsic coagulation pathway is initiated by activation of plasma FXII (Hageman factor). Proteolytically active FXIIa mediates the sequential activation of the serine proteases, FXI and FIX, which also lead to thrombin generation. Until recently, the physiologic relevance of this pathway has remained obscure, as the initial trigger in vivo was not known. On the other hand, in vitro the intrinsic system is easily triggered in plasma using negatively charged materials, such as kaolin, glass, and ellagic acid. Common clotting tests, such as the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), rely on activation of the intrinsic coagulation pathway. In the 1980s, it was proposed that polyanionic vascular components, such as cerebroside sulfates and glycosaminoglycans, function to stimulate FXII activation.3,4 A similar role for collagen was suggested,5,6 but this was refuted by other authors.7-9

Recent studies with mice have greatly increased the interest in the FXII pathway of coagulation. In various in vivo murine models, where thrombus formation was induced by exposure of vascular collagen, it was shown that the absence or inhibition of FXII had a marked suppressive effect on the thrombotic process.10 In addition, in a cerebral artery model of ischemia-reperfusion injury, deficiency in FXII diminished the thrombus formation and reduced the infarction volume in brain vessels.11 Interestingly, in these models, FXI deficiency led to a similar protection of thrombosis.11,12 It was therefore suggested that activated platelets are implicated in the FXII-dependent thrombus formation, but the mechanism was not resolved.10

Platelets become activated by collagen via their immunoglobulin receptor, GPVI. The GPVI-induced signaling pathway involves the ITAM-containing FcR γ-chain coreceptor, and activation of multiple protein tyrosine kinases of the Src and Syk families. Downstream events are the phosphorylation and activation of the adapter protein, LAT, and of a key effector enzyme, phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2).2,13 Both in vivo and in vitro it has been established that collagen-induced signaling from GPVI to PLCγ2 plays a controlling role in flow-mediated thrombus formation.14-16 This signaling causes platelet aggregation and, in addition, leads to platelet procoagulant activity by the surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS), which provides assembly sites for coagulation factors and mediates thrombin generation.15,17

Here, we hypothesized that collagen has a second role in thrombus and clot formation next to stimulating GPVI (ie, by triggering the intrinsic pathway of coagulation via FXII). This hypothesis is tested in the present paper.

Methods

Materials

Standard collagen, equine fibrillar type I Horm (type I/H), came from Nycomed. Other tendon collagens came from Merck: fibrillar type I equine (type I/E); from Sigma-Aldrich: fibrillar type I bovine (type I/B); or was purified as described18 : bovine type I purified (type I/P). Collagen preparations were checked for protein contamination by gel electrophoresis, and dialyzed before use. Collagens were diluted in SKF solution (isotonic glucose solution, pH 2.7-2.9), which also served as solvent control, from Nycomed. Prekallikrein and high-molecular-weight kininogen came from Enzyme Research Laboratories; corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI) and recombinant human FXII, from Haematologic Technologies; recombinant human tissue factor, from Dade Behring; and human FXII-deficient plasma, from George King Bio-Medical. Active-site inactivated FVIIa (FVIIai) was kindly provided by Novo Nordisk; Oregon Green (OG) 488–labeled annexin A5, Alexa Fluor (AF) 546–labeled fibrinogen, and AF633-labeled streptavidin were from Molecular Probes. Thrombin substrate, Z-Gly-Gly-Arg aminomethyl coumarin (Z-GGR-AMC), was from Bachem; and FXIIa substrate Pefachrome 5963, from Pentapharm. Procoagulant phospholipids (PS-phosphatidylcholine-phosphatidylethanolamine, 1:3:1, mol/mol/mol)19 and biotin-labeled anti–human/mouse FXII F3 mAb, raised against the FXII(a) light chain,20,21 were prepared as described. Anti-PLCγ2 mAb DN84 was from DNAX Research Institute; antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 mAb, from Upstate Biotechnology; and FITC–anti-GPIbβ Xia.C3 mAb, from Emfret. Anti-GPVI mAb JAQ1 was a kind gift of Dr B. Nieswandt (Virchow Research Center, Würzburg, Germany). Human α-thrombin calibrator came from Thrombinoscope; d-phenylalanyl-l-prolyl-l-arginine chloromethylketone (PPACK), from Calbiochem. FITC-labeled avidin was from Vector Laboratories. Other materials, including collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum, were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Animals

Animal experiments were approved by the local animal experimental committee at the Universities of Birmingham and Würzburg. Control C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Charles River. Mice homozygously deficient in LAT or PLCγ2 were bred from heterozygotes with a C57Bl/6 background.22,23 Mice homozygous for null mutations in the FXI or FXII gene were generated, as described.24,25 The animals were crossbred for more than 10 generations at a C57Bl/6J background. Per experimental set, wild types, heterozygotes, and homozygotes were used from the same breeding; all animals were genotyped. Blood cell counts of all mouse types were in the normal range.

Blood collection

Blood was freshly taken from healthy volunteers after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was received from Maastricht and Birmingham Universities medical ethical committee; subjects were free from medication for at least 2 weeks. The blood was collected by freely dripping into 1/10 vol 129 mM trisodium citrate (first 2 mL removed). Mouse blood, drawn from animals under anesthesia, was also collected in this citrate solution.15 Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was freshly prepared, as described for human and mouse systems.26,27 Platelet-poor plasma (PPP, 0.5-mL samples) was centrifuged twice at 1500g for 10 minutes, resulting in a platelet count of less than 2 × 106/mL. Platelets were counted with a thrombocounter (Coulter Electronics).

Clotting times and factor levels

Clotting times were measured with a KC-4A coagulometer at 37°C. Tubes were prerinsed with saline containing 1% BSA. Clotting was monitored in human citrate-anticoagulated PRP (2 × 108 platelets/mL) or in PPP supplemented with 10 μM procoagulant phospholipids. Samples were preincubated with collagen or tissue factor for 10 minutes, after which coagulation was triggered by addition of CaCl2 (16.6 mM).

Coagulation times (aPTT, PT) were determined in mouse plasma, as described.10 Plasma levels of coagulation factors in wild-type, FXI−/−, and FXII−/− mice were measured with an automated Blood Coagulation System (Dade Behring), using the reagents for human plasma. Factor levels were similar in wild-type and factor-deficient mice, except for the factor that was knocked out. Plasmas from mice deficient in LAT or PLCγ2 had normal coagulation profiles.

Thrombin generation

Thrombin generation was quantified in citrate-anticoagulated human or mouse PRP (108 platelets/mL), or in PPP supplemented with phospholipids (4 μM), as described.28 Single-donor human plasmas were used. Mouse PRP preparations were pooled from 3 animals with the same genotype. Plasmas were preincubated for 10 minutes with selected inhibitor, after which collagen or vehicle solvent was added. Samples (4 vol) were pipetted into a polystyrene 96-wells plate (Immulon 2HB; Dynex Technologies), already containing 1 vol buffer A (20 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 0.5% BSA). These well plates were selected, as they showed minimal contact activation. Coagulation was started by adding 1 vol buffer B (2.5 mM Z-GGR-AMC, 20 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 100 mM CaCl2, and 6% BSA). Tissue factor was added only if indicated. For human plasma, first-derivative curves of substrate accumulation were converted into nanomolar concentrations using a calibrator for human α-thrombin.28 Thrombin levels in mouse plasma were expressed as arbitrary activity units (AAU), because no calibrator for murine thrombin was available. Samples were run in triplicate (human) or duplicate (mouse).

Collagen binding and activation of FXII

Coverslips were coated with fibrillar type I collagen (1 μg), washed, and blocked with 1% BSA buffer. The collagen-coated coverslips were incubated for 10 minutes with FXII in the presence or absence of prekallikrein/high-molecular-weight kininogen. After triple wash with PBS, coverslips were stained with biotin-labeled anti-FXII(a) mAb (1:50) or biotinylated control IgG, followed by AF633-labeled streptavidin (1:200) or FITC-labeled avidin (1:200). Negative controls were run without anti-FXII(a) mAb. Fluorescence images were recorded by 2-photon laser scanning microscopy at fixed settings of laser power, gain, and pinhole.29

Enzymatic FXIIa activity was determined from the cleavage of Pefachrome FXIIa substrate at 37°C. Incubations contained purified FXII (95 nM), prekallikrein (30 nM), and high-molecular-weight kininogen (30 nM) in Hepes buffer pH 7.45 (136 mM NaCl, 5 mM Hepes, 2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.42 mM NaH2PO4, and 1% BSA). Preincubation was with collagen and/or platelets for 10 to 30 minutes. After addition of 0.8 mM Pefachrome FXIIa substrate, the increase in absorption at 405 nm was determined (linear in time).

Thrombus and clot formation under flow

Coverslips were coated with fibrillar type I collagen (25 μL of 50 μg/mL solution applied at 10 mm2) and blocked with BSA-containing Hepes buffer, pH 7.45. Uncoated coverslips were blocked with the same buffer. Coverslips were placed on a transparent, 50-μm-deep parallel-plate poly(methyl) methacrylate flow chamber, and inserted into a leak-tight chamber holder.30 The chamber was prerinsed with BSA-containing Hepes buffer. Two 1-mL syringes were filled with citrate-anticoagulated blood or isotonic CaCl2/MgCl2 buffer (110 mM NaCl, 5 mM Hepes, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.42 mM NaH2PO4, 13.3 mM CaCl2, and 6.7 mM MgCl2, pH 7.45). Both syringes were connected to the flow chamber via a V-shaped inlet, designed to give optimal fluid mixing. Pumping into the chamber was at equal flow rates, using 2 pulse-free perfusion pumps (WPI), resulting in a final shear rate of 1000 s−1, unless indicated otherwise. This mixing resulted in blood samples with physiologic free Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations of approximately 2 mM. After 4 to 6 minutes of blood flow, the chamber was rinsed with Hepes buffer, pH 7.45, containing 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 U/mL heparin. Fluorescent probe (0.5 μg/mL OG488-annexin A5, 200 μg/mL AF546-fibrinogen) was present in either blood or rinse buffer. Bright-field phase contrast and nonconfocal fluorescent images were recorded, as described.15 Frequency distribution of platelet aggregate sizes was assessed by morphometric analysis of phase-contrast images.31 Confocal fluorescence images were scanned using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a C1 confocal head. Scanning was at 50 lines per second and 2 × Kalman averaging. The images were processed with ImagePro software.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Cleavage of FXII into FXIIa was detected by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under reduced conditions, and subsequent Western blotting.32 Citrated PRP (108 platelets/mL) was activated with CaCl2 with or without collagen (40 μg/mL) or kaolin (50 μg/mL) for more than 10 minutes. After centrifugation to remove clots, the plasma samples were either diluted (1:10) in sample buffer and directly applied to gel, or used for immunoprecipitation with anti-FXII(a) F3 mAb. Western blots were stained for FXII(a) with F3 mAb, and visualized with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

For probing PLCγ2 activation, platelets (5 × 108/mL) from wild-type mice and mice heterozygously or homozygously deficient in LAT or PLCγ2 were stimulated with type I/H collagen (10 μg/mL) for 90 seconds in the presence of EGTA to prevent aggregation. Activated platelets were lysed, and PLCγ2 was immunoprecipitated using anti-PLCγ2 mAb.33 Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by gel electrophoresis and subjected to Western blotting. Blots were probed for phosphotyrosine and reprobed for PLCγ2.34

Statistics

Significance of differences was determined with the Mann-Whitney U test or the independent samples t test, as appropriate, using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS 11.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Size distribution of platelet thrombi was evaluated using the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at P value less than .05.

Results

Collagen enhances clotting and thrombin generation in a FXII-dependent way

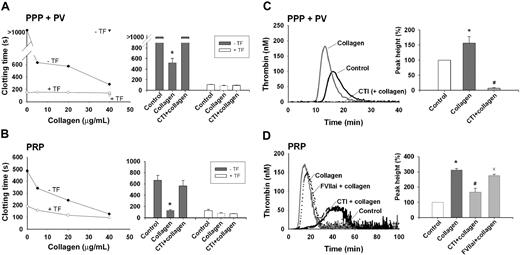

The effect of collagen on coagulation was studied in human plasma triggered with CaCl2 (no tissue factor). In a dose-dependent way, type I (Horm, I/H) collagen fibers markedly shortened the time to clot formation. At a concentration of 40 μg/mL, the clotting time reduced from more than 500 to approximately 200 seconds, regardless of whether phospholipids or platelets were present as procoagulant lipid surface (Figure 1A-B). Type I collagens from other sources (designated as I/E, I/B, and I/P) were similarly effective (compare next paragraph). Prolongation of the incubation time with collagen from 10 to 30 minutes further shortened the clotting time (not shown). Treatment with collagenase from C histolyticum abolished this reduction, thus precluding effect of impurities in the collagen preparation. In normal human plasma, the faster clotting by collagen was prevented with the FXII inhibitor, CTI, at an IC50 of 1.2 μM (Figure 1A-B). Markedly, no collagen effect was observed in FXII-deficient plasma. Plasma treatment with tissue factor/CaCl2 also resulted in considerable shortening of the clotting time, but this effect was insensitive to CTI.

Collagen enhances coagulation in the absence of tissue factor. Human citrate-anticoagulated plasma with phospholipid vesicles (PPP + PV) or platelets (PRP) was pretreated with 4 μM CTI or 100 nM FVIIai, as indicated. Preparations were then incubated with collagen type I Horm (type I/H) or vehicle solvent (control) for 10 minutes. Activation was with 16.6 mM CaCl2; tissue factor (1 pM) was present only if indicated. (A,B) Collagen shortens the clotting time when using normal plasma (circles), but not FXII-deficient plasma (triangles). Bar graphs represent clotting times obtained with normal plasma and 40 μg/mL collagen. Note the potent collagen effect without tissue factor (gray), but not with tissue factor present (white). (C,D) Collagen (5 μg/mL) potentiates thrombin generation in the presence of phospholipids and platelets. Shown are representative thrombin generation curves, and bar graphs of thrombin peak height (relative to the control condition of vehicle solvent). Mean ± SEM; n = 3-5 donors; *P < .05 vs control; #P < .05 vs condition with collagen.

Collagen enhances coagulation in the absence of tissue factor. Human citrate-anticoagulated plasma with phospholipid vesicles (PPP + PV) or platelets (PRP) was pretreated with 4 μM CTI or 100 nM FVIIai, as indicated. Preparations were then incubated with collagen type I Horm (type I/H) or vehicle solvent (control) for 10 minutes. Activation was with 16.6 mM CaCl2; tissue factor (1 pM) was present only if indicated. (A,B) Collagen shortens the clotting time when using normal plasma (circles), but not FXII-deficient plasma (triangles). Bar graphs represent clotting times obtained with normal plasma and 40 μg/mL collagen. Note the potent collagen effect without tissue factor (gray), but not with tissue factor present (white). (C,D) Collagen (5 μg/mL) potentiates thrombin generation in the presence of phospholipids and platelets. Shown are representative thrombin generation curves, and bar graphs of thrombin peak height (relative to the control condition of vehicle solvent). Mean ± SEM; n = 3-5 donors; *P < .05 vs control; #P < .05 vs condition with collagen.

Thrombin generation experiments were carried out to study the mechanism of collagen-enhanced coagulation. In the absence of tissue factor, type I/H collagen fibers (EC50 2 μg/mL) reduced the lag time to thrombin generation and increased the thrombin peak height with phospholipids present as lipid surface (Figure 1C). CTI was completely inhibitory here. Collagen furthermore increased the thrombin generation with platelets present (Figure 1D). Here, the collagen effect was significantly but incompletely antagonized by CTI, and only little influenced by FVIIai (100 nM), a tissue factor inhibitor. Thrombin activity measurements, performed in PPP and PRP incubated with various doses of collagen, indicated a dose-dependent accumulation of thrombin that was greatly increased in the presence of platelets (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Together, these data demonstrate that type I collagen enhances the thrombin generation process, likely via activation of FXII, in a way potentiated by platelets or procoagulant phospholipids, providing a procoagulant membrane surface.

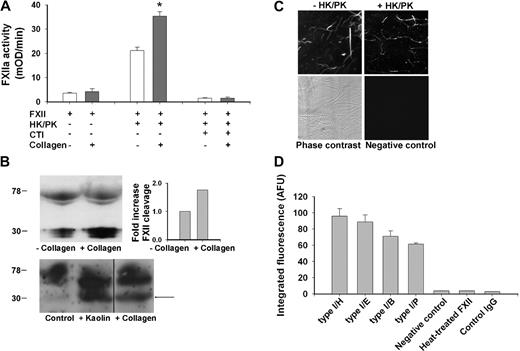

Collagen binds and activates factor XII

The activating effect of collagen on FXII was directly measured in a plasma-free test system with purified coagulation factors. When incubated with high-molecular-weight kininogen and prekallikrein, recombinant FXII showed limited proteolytic activity to a chromogenic FXIIa substrate, most likely due to kallikrein-mediated autoactivation of FXII (Figure 2A). Addition of type I collagen substantially increased the chromogenic activity, whereas CTI was completely inhibitory, demonstrating specificity for FXIIa. Prolonged incubation with collagen from 10 to 30 minutes resulted in an additional, 2.5-fold increase in FXIIa activity.

Collagen enhances conversion of FXII into active FXIIa. (A) Collagen-induced FXII activation in plasma-free system. Assay samples contained 95 nM FXII, 30 nM prekallikrein (PK), 30 nM high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK), 5 μg/mL collagen type I/H, and 4 μM CTI, as indicated. Chromogenic FXIIa activity was determined at 37°C from the cleavage of Pefachrome FXIIa substrate. (B) Collagen-induced activation of FXII in coagulating plasma. PRP (108 platelets/mL) was activated with 16.6 mM CaCl2 in the presence of 40 μg/mL collagen type I/H or vehicle solvent (top panel). Shown is representative Western blot of plasma immunoprecipitates stained for FXII(a); bars give increased ratio of cleaved FXIIa light chain (28-30 kDa) to uncleaved FXII (78-80 kDa) normalized to the condition without collagen (n = 2). In addition, PRP was activated similarly but also with kaolin (50 μg/mL) present (bottom panel). Given is representative Western blot of diluted plasma stained for FXII(a). Vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (C,D) Binding of FXII to collagen. Coverslips with immobilized type I collagen were incubated for 10 minutes with FXII plus or minus PK/HK (concentrations as in panel A), then rinsed and stained with biotin-labeled anti-FXII(a) mAb and FITC-avidin. (C) Two-photon laser scanning images (180 × 180 μm) of fibers of FXII-stained collagen type I/H. Negative control represents condition where primary anti-FXII(a) mAb was omitted. (D) Integrated fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) of immunostaining for FXII with various type I collagens. Controls were incubations with heat-treated FXII (5 minutes at 56°C) or biotin-labeled IgG. Mean ± SEM; n = 3-4; *P < .05 vs condition without collagen.

Collagen enhances conversion of FXII into active FXIIa. (A) Collagen-induced FXII activation in plasma-free system. Assay samples contained 95 nM FXII, 30 nM prekallikrein (PK), 30 nM high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK), 5 μg/mL collagen type I/H, and 4 μM CTI, as indicated. Chromogenic FXIIa activity was determined at 37°C from the cleavage of Pefachrome FXIIa substrate. (B) Collagen-induced activation of FXII in coagulating plasma. PRP (108 platelets/mL) was activated with 16.6 mM CaCl2 in the presence of 40 μg/mL collagen type I/H or vehicle solvent (top panel). Shown is representative Western blot of plasma immunoprecipitates stained for FXII(a); bars give increased ratio of cleaved FXIIa light chain (28-30 kDa) to uncleaved FXII (78-80 kDa) normalized to the condition without collagen (n = 2). In addition, PRP was activated similarly but also with kaolin (50 μg/mL) present (bottom panel). Given is representative Western blot of diluted plasma stained for FXII(a). Vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. (C,D) Binding of FXII to collagen. Coverslips with immobilized type I collagen were incubated for 10 minutes with FXII plus or minus PK/HK (concentrations as in panel A), then rinsed and stained with biotin-labeled anti-FXII(a) mAb and FITC-avidin. (C) Two-photon laser scanning images (180 × 180 μm) of fibers of FXII-stained collagen type I/H. Negative control represents condition where primary anti-FXII(a) mAb was omitted. (D) Integrated fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) of immunostaining for FXII with various type I collagens. Controls were incubations with heat-treated FXII (5 minutes at 56°C) or biotin-labeled IgG. Mean ± SEM; n = 3-4; *P < .05 vs condition without collagen.

Because the chromogenic substrate is also cleaved by thrombin, it could not be used to detect active FXII in coagulating plasma. Hence, another approach was followed. The activation and cleavage of FXII was examined by incubating PRP with CaCl2 and collagen, and analyzing the plasma products by Western blot analysis using an anti-FXII(a) mAb (Figure 2B). Western blots from plasma immunoprecipitates showed that the presence of collagen increased the ratio of cleaved FXIIa light chain (28-30 kDa) to full-length FXII (78 kDa) by approximately 1.7-fold. Blots from total plasma indicated that collagen had a similar but less strong effect as kaolin on FXII cleavage, as indicated by appearance of the 28- to 30-kDa band (Figure 2B arrow).

The results suggested that FXII can be activated by binding to collagen. At first, this was studied by Biacore experiments using collagen-coated microchips. This gave a dose-dependent, reversible binding of FXII that, however, partly consisted of binding to the chip material rather than to the collagen (P.E.J.M., unpublished data, 2008). As an alternative approach, FXII-collagen binding was determined by immunofluorescence. Coverslips with immobilized collagen type I/H were incubated with recombinant FXII and then immunostained for this factor. Two-photon laser scanning microscopy showed that FXII was present only at the sites of collagen fibers; this binding was not affected by addition of prekallikrein/kininogen (Figure 2C). Type I collagens fibers from other sources (types I/E, I/B, and I/P) gave a similar staining pattern for FXII (Figure 2D). On the other hand, no staining was detectable, when anti-FXII(a) mAb was omitted or when FXII was heat-treated before incubation with collagen. Together, these results point to binding of FXII to collagen fibers, resulting in increased activation of FXII with kininogen/prekallikrein.

FXII contributes to collagen-dependent thrombus formation under conditions of flow and coagulation

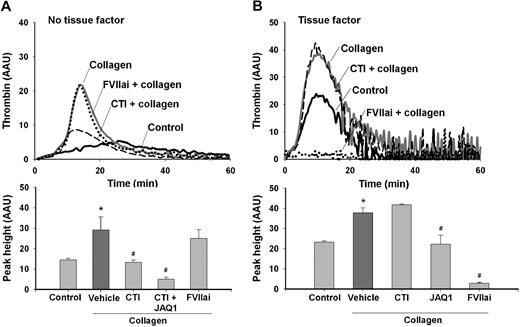

Mouse plasmas were used for additional thrombin generation experiments. In CaCl2-activated PRP from wild-type mice, type I/H collagen (5 μg/mL) markedly increased the thrombin peak height (Figure 3A). Other collagens (type I/B and I/P, 5 μg/mL) had a similar increasing effect, amounting to approximately 225%. The collagen effect was partly inhibited by CTI (IC50 0.8 μM), whereas FVIIai was not effective (Figure 3A). In combination with anti-GPVI mAb, JAQ1, thrombin generation was almost completely suppressed. This agreed with previous experiments, showing that JAQ1 antibody fully inhibits GPVI-dependent platelet procoagulant activity.15 Platelet exposure of PS was required, because preincubation with 5 μg/mL annexin A5 also abrogated all thrombin generation (not shown). Upon stimulation with tissue factor, JAQ1 but not CTI suppressed the enhancing effect of collagen on thrombin generation (Figure 3B). Together, these experiments suggested the presence of 2 different mechanisms of collagen-stimulated PS exposure and thrombin generation (without tissue factor), one involving platelet activation via GPVI and the other one by FXII.

Platelet GPVI and FXII activation contribute to collagen-promoted thrombin generation in mouse plasma. Thrombin generation was measured in PRP from wild-type mice that was treated with vehicle solvent (control) or collagen type I/H (5 μg/mL) and activated with CaCl2. Plasma samples were preincubated with FVIIai (100 nM), CTI (4 μM), and/or JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL). Thrombin generation was determined in the absence (A) or presence (B) of tissue factor (1 pM). Thrombin levels are given as arbitrary activity units (AAU). Note the suppression of collagen-dependent thrombin generation by JAQ1 mAb and CTI. Mean ± SEM; n = 4; *P < .05 vs control; #P < .05 vs condition with collagen.

Platelet GPVI and FXII activation contribute to collagen-promoted thrombin generation in mouse plasma. Thrombin generation was measured in PRP from wild-type mice that was treated with vehicle solvent (control) or collagen type I/H (5 μg/mL) and activated with CaCl2. Plasma samples were preincubated with FVIIai (100 nM), CTI (4 μM), and/or JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL). Thrombin generation was determined in the absence (A) or presence (B) of tissue factor (1 pM). Thrombin levels are given as arbitrary activity units (AAU). Note the suppression of collagen-dependent thrombin generation by JAQ1 mAb and CTI. Mean ± SEM; n = 4; *P < .05 vs control; #P < .05 vs condition with collagen.

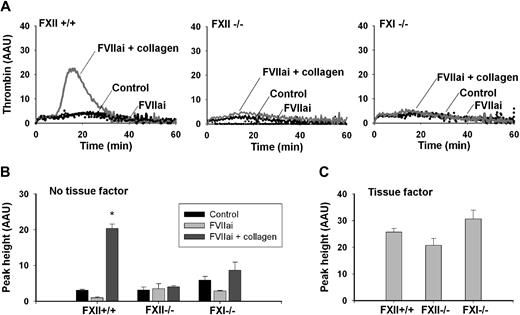

To monitor contribution of the intrinsic pathway to thrombin generation, we examined the effects of deficiency in FXII or FXI. To avoid variation in platelet responsiveness, plasmas from wild-type, FXII−/−, and FXI−/− mice were reconstituted with pooled wild-type platelets. Strikingly, in reconstituted PRP from FXII−/− or FXI−/− animals, the collagen effect on thrombin peak height was abolished (Figure 4A-B). Yet, when stimulated with tissue factor, the knockout and wild-type plasmas showed similar thrombin generation profiles, implicating normal activity of the extrinsic coagulation system (Figure 4C).

Deficiency in FXII or FXI abrogates collagen enhancement of thrombin generation. Plasma (PPP) from wild-type, FXII−/−, or FXI−/− mice was supplemented with washed platelets, which were pooled from wild types (108 platelets/mL, fc). Samples were pretreated with collagen type I/H (5 μg/mL), vehicle solvent (control), and/or FVIIai (100 nM), as indicated. Thrombin generation was triggered by CaCl2 without (A-B) or with (C) tissue factor (1 pM). Shown are representative thrombin generation curves (A) and thrombin peak height (B,C); thrombin is expressed as arbitrary activity units. Note the impairment of collagen effects with FXII−/− or FXI−/− plasma. Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs control.

Deficiency in FXII or FXI abrogates collagen enhancement of thrombin generation. Plasma (PPP) from wild-type, FXII−/−, or FXI−/− mice was supplemented with washed platelets, which were pooled from wild types (108 platelets/mL, fc). Samples were pretreated with collagen type I/H (5 μg/mL), vehicle solvent (control), and/or FVIIai (100 nM), as indicated. Thrombin generation was triggered by CaCl2 without (A-B) or with (C) tissue factor (1 pM). Shown are representative thrombin generation curves (A) and thrombin peak height (B,C); thrombin is expressed as arbitrary activity units. Note the impairment of collagen effects with FXII−/− or FXI−/− plasma. Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs control.

Blood flow over a collagen surface, under conditions of coagulation with tissue factor, is known to lead to rapid formation of thrombi with procoagulant platelets and fibrin clots.29 We performed similar flow experiments in the absence of tissue factor, to study the contribution of FXII to collagen-dependent coagulation and thrombus formation. Citrate-anticoagulated blood from wild-type mice was mixed with a CaCl2/MgCl2 buffer, and perfused over immobilized type I collagen fibers at a moderate shear rate of 1000 s−1. Trace amounts of OG488-annexin A5 were added to the blood to monitor the formation of PS-exposing platelets. During the flow, collagen-adhered platelets formed aggregates, whereas some of the single platelets bound annexin A5. After several minutes of flow, once fibrin fibers were formed, the aggregates also started to bind annexin A5, which resulted in a strong overall increase in fluorescence (Figure 5A). The accumulation of fluorescence was suppressed in the presence of CTI, but only slightly reduced with FVIIai. Markedly, combined treatment of the blood with CTI and anti-GPVI mAb JAQ1 resulted in virtual absence of annexin fluorescence. Addition of CTI had similar effects at a reduced shear rate of 500 s−1 (not shown).

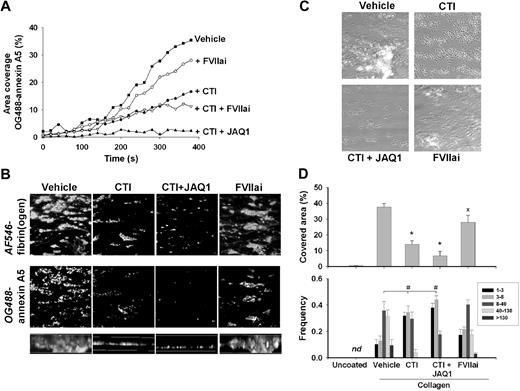

Inhibition of GPVI or FXII suppresses collagen-dependent thrombus formation and platelet procoagulant activity. Blood from wild-type mice was flowed for 4 minutes over type I/H collagen under coagulant condition by coperfusion with CaCl2/MgCl2 buffer at a shear rate of 1000 s−1. Blood was pretreated with saline vehicle (control), CTI (4 μM), JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL), and FVIIai (100 nM), as indicated. No tissue factor was added. (A) Accumulation of PS-exposing platelets during perfusion (OG488-annexin A5 added to the blood). Representative experiment of 3 performed. (B) Projected confocal stacks (180 × 180 μm; height, 50 μm) of thrombi costained with AF546-fibrinogen and OG488-annexin A5. Bottom panels (side views) represent thrombus height. (C) Representative phase-contrast images (120 × 120 μm) of thrombi after perfusion. (D top panel) Surface area covered by all thrombi. (Bottom panel) Frequency distribution of small and large platelet thrombi (estimated number of platelets per feature indicated in box). Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs vehicle control; #P < .05, χ2 test.

Inhibition of GPVI or FXII suppresses collagen-dependent thrombus formation and platelet procoagulant activity. Blood from wild-type mice was flowed for 4 minutes over type I/H collagen under coagulant condition by coperfusion with CaCl2/MgCl2 buffer at a shear rate of 1000 s−1. Blood was pretreated with saline vehicle (control), CTI (4 μM), JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL), and FVIIai (100 nM), as indicated. No tissue factor was added. (A) Accumulation of PS-exposing platelets during perfusion (OG488-annexin A5 added to the blood). Representative experiment of 3 performed. (B) Projected confocal stacks (180 × 180 μm; height, 50 μm) of thrombi costained with AF546-fibrinogen and OG488-annexin A5. Bottom panels (side views) represent thrombus height. (C) Representative phase-contrast images (120 × 120 μm) of thrombi after perfusion. (D top panel) Surface area covered by all thrombi. (Bottom panel) Frequency distribution of small and large platelet thrombi (estimated number of platelets per feature indicated in box). Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs vehicle control; #P < .05, χ2 test.

Two-color confocal images of wild-type thrombi that were formed in the presence of AF546-fibrinogen and OG488-annexin A5 showed massive staining of the platelet aggregates for fibrin(ogen) and annexin A5 (Figure 5B). Blood treatment with CTI, but not FVIIai, resulted in smaller aggregates with reduced labeling of fibrin(ogen) and annexin A5. Combined treatment with CTI and JAQ1 mAb left only single platelets and small platelet clusters at the collagen surface, which mostly did not bind annexin A5. With CTI or CTI/JAQ1 present, mean thrombus volume (per 1000 μm3), as measured from fibrin(ogen) staining, reduced from 287 (± 33) to 26 (± 1.0) or 7.1 (± 1.8) μm3, respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 4). FVIIai only slightly reduced thrombus volume to 223 (± 38) μm3.

Phase-contrast images taken at the end of the perfusions confirmed that CTI or CTI/JAQ1 reduced the surface area coverage of thrombi from 39% to 13% or 7%, respectively (Figure 5C-D top panels). Morphometric analysis of these images showed that CTI, especially with JAQ1 present as well, eliminated the formation of large (fibrin-containing) aggregates, leaving only single platelets and small platelet clusters on the collagen surface (Figure 5D bottom panel). The thrombi on collagen were also immunostained for FXII. This resulted in staining of the collagen fibers, but not of the platelet aggregates (supplemental Figure 2). Importantly, with uncoated coverslips, no platelets were deposited and no fibrin was formed.

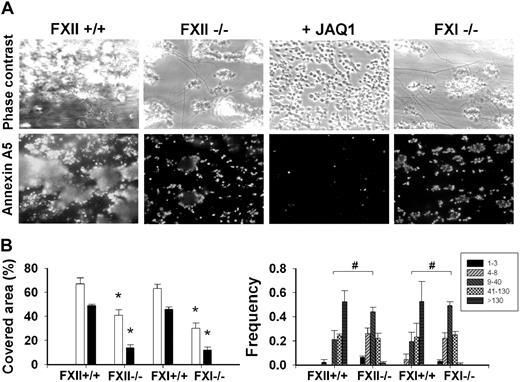

Flow chamber studies were also carried out with blood from factor-deficient mice. In comparison with wild type, thrombus formation and platelet PS exposure (OG488–annexin A5 fluorescence) were significantly reduced in FXII−/− blood (Figure 6A). Only small aggregates were present, which stained for annexin A5 at sites of contact with collagen (Figure 6B). Fibrin formation was reduced, thus pointing to diminished thrombin activity. In case of FXI−/− blood, thrombus formation and PS exposure diminished similarly as with FXII−/− blood (Figure 6).

Deficiency in FXII or FXI impairs collagen-dependent thrombus and platelet procoagulant activity. Blood from FXII−/− or FXI−/− mice or corresponding wild types was flowed over collagen under coagulant condition for 4 minutes (Figure 5). Blood was pretreated with JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL), as indicated. Thrombi were poststained with OG488-annexin A5. (A) Representative phase-contrast and fluorescent images (175 × 225 μm). (B left panel) Surface area covered by thrombi (□) and annexin A5 fluorescence (■). (Right panel) Frequency distribution of small and large platelet thrombi (estimated number of platelets per feature indicated in box). Mean ± SEM; n = 5-7; *P < .05 vs corresponding wild type; #P < .05, χ2 test.

Deficiency in FXII or FXI impairs collagen-dependent thrombus and platelet procoagulant activity. Blood from FXII−/− or FXI−/− mice or corresponding wild types was flowed over collagen under coagulant condition for 4 minutes (Figure 5). Blood was pretreated with JAQ1 mAb (40 μg/mL), as indicated. Thrombi were poststained with OG488-annexin A5. (A) Representative phase-contrast and fluorescent images (175 × 225 μm). (B left panel) Surface area covered by thrombi (□) and annexin A5 fluorescence (■). (Right panel) Frequency distribution of small and large platelet thrombi (estimated number of platelets per feature indicated in box). Mean ± SEM; n = 5-7; *P < .05 vs corresponding wild type; #P < .05, χ2 test.

Control experiments showed that CTI or FVIIai did not further affect thrombus formation with FXII−/− blood. Addition of CTI or FVIIai insignificantly changed the surface area coverage of thrombi from 40.7% (± 4.5%) to 40.5% (± 1.6%) or 38.5% (± 3.8%), respectively; and changed surface area coverage by PS-exposing platelets from 12.2% (± 4.6%) to 9.6% (± 4.6%) or 8.3% (± 0.7%), respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 3-5). To determine whether the remaining PS exposure was due to GPVI-induced platelet activation, FXII−/− blood was treated with JAQ1 mAb. This further abolished the formation of platelet aggregates, and it almost completely eliminated PS exposure (Figure 6A). Together, these results suggest that flow of coagulating blood over collagen (in the absence of tissue factor) triggers GPVI-induced platelet activation as well as FXII-driven thrombin generation, both of which pathways contribute to both thrombus formation and PS exposure.

Platelet signaling via LAT and PLCγ2 contributes to collagen-dependent thrombus formation under conditions of flow and coagulation

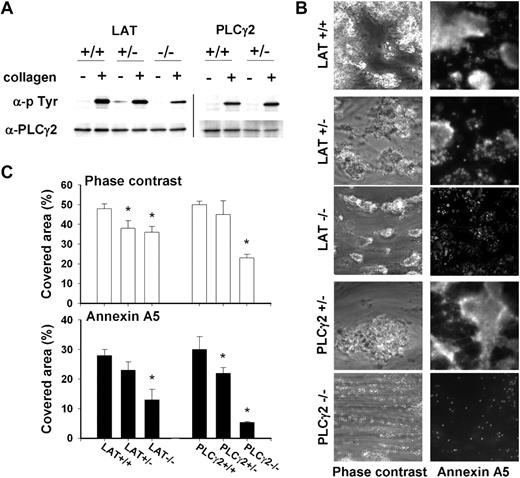

To confirm that GPVI-induced platelet activation contributes to the collagen effects on coagulation, we used mice (partly) deficient in the adapter protein LAT or the effector protein PLCγ2, which are key signaling components downstream of GPVI. Platelets from these mice show impaired activation by collagen, but not by thrombin or ADP.35,36 Control experiments indicated that, in comparison with wild type, platelets from LAT−/− mice were strongly but not completely decreased in collagen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 (Figure 7A). Platelets from heterozygous LAT+/− or PLCγ2+/− mice, though, did not show marked changes in PLCγ2 phosphorylation. This was confirmed by analysis of total collagen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation, giving a reduction in LAT−/− and PLCγ2−/− platelets, but not in LAT+/− and PLCγ2+/− platelets (not shown).

Deficiency in LAT or PLCγ2 impairs collagen-dependent thrombus formation and platelet procoagulant activity on collagen under coagulant condition. (A) Effect of collagen type I/H (10 μg/mL) on tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 in platelets from wild types or mice (heterozygously) deficient in LAT or PLCγ2. Western blots of PLCγ2 immunoprecipitates were stained for antiphosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), then reprobed with anti-PLCγ2 mAb (representative for 3 sample sets). Vertical line has been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. (B) Blood from wild-type or deficient mice was flowed over collagen under coagulant condition (Figure 5). Platelet-fibrin thrombi were poststained with OG488-annexin A5. Shown are representative phase-contrast and fluorescent images (180 × 180 μm). (C) Surface area covered by thrombi (□) and annexin A5 fluorescence (■). Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs corresponding wild type.

Deficiency in LAT or PLCγ2 impairs collagen-dependent thrombus formation and platelet procoagulant activity on collagen under coagulant condition. (A) Effect of collagen type I/H (10 μg/mL) on tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ2 in platelets from wild types or mice (heterozygously) deficient in LAT or PLCγ2. Western blots of PLCγ2 immunoprecipitates were stained for antiphosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), then reprobed with anti-PLCγ2 mAb (representative for 3 sample sets). Vertical line has been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. (B) Blood from wild-type or deficient mice was flowed over collagen under coagulant condition (Figure 5). Platelet-fibrin thrombi were poststained with OG488-annexin A5. Shown are representative phase-contrast and fluorescent images (180 × 180 μm). (C) Surface area covered by thrombi (□) and annexin A5 fluorescence (■). Mean ± SEM; n = 4-5; *P < .05 vs corresponding wild type.

Thrombin generation measurements were performed with PRP from LAT−/− and PLCγ2−/− mice. In the absence of collagen, either type of PRP had a normal thrombin generation profile, when triggered with tissue factor (not shown, but see Munnix et al29 ). In the absence of tissue factor, collagen (5 μg/mL type I/H) increased the thrombin peak height in wild-type PRP to 209% (± 34%). In LAT−/− or PLCγ2−/− PRP, this collagen effect was significantly reduced to 114% (± 9%) or 127 (± 7%), respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 4). In PLCγ2−/− PRP, CTI further reduced the stimulation by collagen of thrombin generation by 17%. Together, this pointed to a contribution of the platelet signaling proteins, jointly with the FXII pathway, to collagen-dependent thrombin generation.

Earlier, it was reported that, with tissue factor present, LAT and PLCγ2 play a role in GPVI-dependent PS exposure and fibrin clot formation.29 We used blood from the deficient mice to study thrombus formation on collagen in the absence of tissue factor. In comparison with wild-type blood, formation of large thrombi with fibrin was suppressed in case of heterozygous LAT+/− blood, whereas platelet PS exposure (annexin A5 fluorescence) was decreased in heterozygous PLCγ2+/− blood (Figure 7B-C). Homozygous deficiency in LAT gave a marked reduction in thrombus formation, leaving only medium-sized thrombi with limited PS exposure. Complete deficiency in PLCγ2 had an even stronger effect, with only small platelet aggregates and few PS-exposing platelets left on the collagen surface.

The role of GPVI-induced platelet activation in this flow model was substantiated by treatment of the blood from deficient mice with the active-site thrombin inhibitor, PPACK, to suppress coagulation. In case of wild-type blood, both aggregated and PS-exposing platelets formed at the collagen surface (no fibrin clots). Heterozygous and homozygous deficiency in LAT or PLCγ2 significantly reduced PS exposure, whereas homozygous deficiency was needed to suppress platelet aggregate formation (Figure S3). Hence, both signaling proteins are implicated in collagen-dependent PS exposure, also in the absence of thrombin.

Discussion

In this paper, we have defined a novel role for vascular type I collagen fibers, by triggering the intrinsic pathway of coagulation via FXII and FXI activation. Evidence for such a role comes from the findings that collagen fibers (1) shorten plasma clotting times in a FXII-dependent way; (2) enhance thrombin generation via FXII, and (3) stimulate flow-dependent thrombus and fibrin formation and platelet procoagulant activity. Collagen-induced stimulation of the intrinsic coagulation system was detected in the absence of platelets, but was enhanced in the presence of platelets both in humans and mice. The contribution of platelets, in particular, involved collagen-induced stimulation of procoagulant activity via GPVI signaling to LAT and PLCγ2. Earlier work has shown that GPVI causes a potent rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which is a prerequisite for surface exposure of procoagulant PS.15,37 The present data hence point to a dual role of collagen in thrombus formation: it stimulates platelet activation via GPVI and facilitates FXII activation to produce thrombin. This dual thrombogenic effect of collagen may explain why vascular collagen is effective in triggering thrombus formation in animal thrombosis models.2,14

The dose-dependent stimulating effects of collagen fibers on FXII-dependent clotting time and thrombin generation suggested that FXII can bind to the collagen and becomes activated. Type I collagens purified from different sources were similarly effective, suggesting this is a general collagen property. By immunostaining, we could confirm that these collagens bind FXII, but the extent of binding was not increased with kininogen/prekallikrein. Yet, in vitro measurements of FXIIa chromogenic activity showed that these cofactors were required for the collagen enhancement of FXII activation. The binding site for FXII within the collagen triple-helical structure still needs to be identified.

Recent work showed that FXII and FXI significantly contribute to the thrombotic process in several mouse models of experimental arterial thrombosis.10,11,38 The present results provide a mechanistic explanation for this finding. Thrombin generation experiments with control and FXII−/− and FXI−/− plasmas pointed to a collagen-induced effect on FXII and FXI activation, which results in sufficient amounts of activated coagulation factors to start thrombin generation. Platelets exposing PS, also activated by collagen, most likely provide the necessary membrane surface for propagation of the coagulation process. The importance of PS exposure was apparent from the complete abolition of thrombin generation in the presence of blocking annexin A5.

A similar interaction mechanism may operate under flow conditions. We found that the formation of thrombi composed of fibrin-binding and PS-exposing platelets under flow was highly sensitive to blockage/absence of FXII or FXI as well as by blockage/absence of platelet GPVI activation. Furthermore, the stimulation of PS exposure by GPVI was detected not only under coagulant conditions, but also when thrombin was blocked with PPACK. This confirmed the importance of platelet activation for the establishment of fibrin thrombi. The marked similarity in effects of FXII and FXI deficiency was in agreement with the similar reductions, earlier seen in FXII−/− and FXI−/− mice for thrombus formation in vivo.39 In line with this is a recent study using human plasma, indicating that FXII is the main activator of FXI.40

Isolated blood contains trace amounts of (blood-borne) tissue factor, which have been detected on leukocytes, (activated) platelets, and microparticles.41,42 In the present experiments, blocking of tissue factor activity with FVIIai had a slight inhibitory effect on collagen-induced thrombin generation and thrombus formation, although this contrasted to the much larger inhibition by CTI or the absence of FXII. Hence, these data stipulate a clear role of collagen in stimulation of the intrinsic coagulation pathway that is independent of tissue factor and FVIIa. Conversely, the FXII-dependent effect of collagen on thrombin generation (ie, independent of GPVI-induced platelet activation) disappeared in the presence of picomolar concentrations of tissue factor. The physiologic implication may be that FXII stimulation by collagen is most relevant under conditions where local tissue factor activity is limited. As platelets do not seem to bind FXII, their role in coagulation is most prominent by providing a procoagulant membrane surface for activation of factor X and prothrombin. However, our results do not exclude that platelets can also contribute in a different way to the thrombus-forming process (eg, by production of polyphosphates).43

Despite the recognized role of FXII in mouse thrombosis models, the function of human FXII in plasma is still a matter of debate. Several clinical studies with healthy subjects reported that low plasma levels of FXII are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.20,44-46 However, this association was absent in subjects with FXII levels below 10% of normal.45 This has led to the question whether low FXII levels may be a cause or in fact a consequence of cardiovascular disease.47 Yet, FXII is dispensable for normal hemostasis. It remains to be established how the thromboprotective effect of FXII deficiency in mice translates to the human situation. On the other hand, the similarity in functions in vitro of human and mouse FXII suggests a common contribution to in vivo thrombus formation as well.

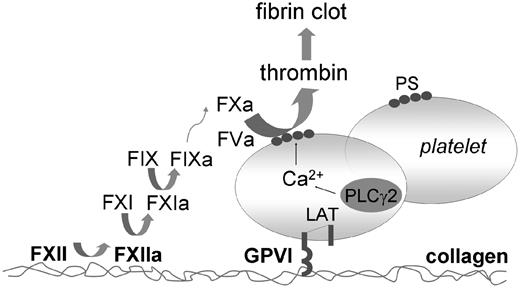

In summary, the present results point to a dual role of exposed collagen in thrombus and fibrin clot formation under conditions where tissue factor is limited (Figure 8). Exposed collagen fibers activate platelets via the GPVI-LAT-PLCγ2 signaling pathway, causing platelet aggregation and exposure of procoagulant PS. In addition, collagen binds FXII and causes its activation. The result is activation of FXI and other coagulation factors, the process of which is facilitated at the membrane of PS-exposing platelets. Positive feedback by formed thrombin enhances these reactions to produce a stable fibrin thrombus.

Scheme of dual role of collagen in thrombus formation. Collagen binds and facilitates FXII activation, which results in sequential activation of FXI and FIX, and subsequent coagulation. Collagen-adhered platelets become activated via their GPVI receptors. Platelet signaling via LAT and PLCγ2 results in potent Ca2+ rises and surface exposure of PS. This procoagulant surface mediates the formation of coagulation factor complexes that causes generation of FXa and thrombin. The formed thrombin in turn feeds back to increase PS exposure. Jointly, these pathways lead to massive formation of platelet-fibrin clots, even under conditions where tissue factor is limitedly available.

Scheme of dual role of collagen in thrombus formation. Collagen binds and facilitates FXII activation, which results in sequential activation of FXI and FIX, and subsequent coagulation. Collagen-adhered platelets become activated via their GPVI receptors. Platelet signaling via LAT and PLCγ2 results in potent Ca2+ rises and surface exposure of PS. This procoagulant surface mediates the formation of coagulation factor complexes that causes generation of FXa and thrombin. The formed thrombin in turn feeds back to increase PS exposure. Jointly, these pathways lead to massive formation of platelet-fibrin clots, even under conditions where tissue factor is limitedly available.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO 11.400.0076), the Netherlands Heart Foundation (2005B079), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and the British Heart Foundation (S.P.W.).

Authorship

Contribution: P.E.J.v.d.M. performed experiments, analyzed data, designed research, and finalized the paper; I.C.A.M., J.M.A., J.M.E.M.C., and M.J.E.K. performed experiments and analyzed data; J.W.P.G.-R. and H.M.S. performed experiments, interpreted data, and contributed analytical tools; S.P.W. contributed analytical tools, designed research, and drafted the paper; T.R. contributed analytical tools, designed research, and drafted and finalized the paper; and J.W.M.H. designed research and finalized the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Johan W. M. Heemskerk, Department of Biochemistry (CARIM), Maastricht University, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands; e-mail: jwm.heemskerk@bioch.unimaas.nl.

References

Author notes

*T.R. and J.W.M.H. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal