Abstract

Therapeutic options for multiple myeloma (MM) patients have changed quickly in recent years and uncertainty has arisen about optimal approaches to therapy. A reasonable goal of MM treatment in younger “transplant eligible” patients is to initiate therapy with a target goal of durable complete remission, and the anticipated consequence of long-term disease control. To achieve this goal we recommend induction therapy with multi-agent combination chemotherapies (usually selected from bortezomib, lenalidomide, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and corticosteriods) which when employed together elicit frequent, rapid, and deep responses. We recommend consolidation with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation in the majority of patients willing and able to undergo this procedure and subsequent maintenance therapy, especially in those failing to achieve a complete response or at high risk for early relapse based on prognostic, genetically defined risk factors. Defining genetic risk for early relapse is therefore an important aspect of early diagnostic testing and attention to minimizing expected toxicities once therapy begins is critical in ensuring the efficacy of modern combination therapy approaches. When access to newer drugs is restricted participation in clinical trials should be pursued.

Introduction

Therapy for multiple myeloma (MM) has advanced with gratifying speed over the past 5\tto 7 years1 and, with this progress, a degree of uncertainty has arisen about optimal approaches to therapy, particularly in the newly diagnosed patient. Indeed, using modern therapeutic strategies, living with MM for a decade or longer has now become a reality for a significant proportion of patients.2 Nevertheless, in many instances, randomized trial data that provide definitive evidence-based guidance on how best to achieve this goal is lacking. This article therefore seeks to offer practical guidance in a rapidly changing landscape and outlines our current belief about the goals of therapy and our personal approach to treating the younger myeloma patient.

Our approach to treatment in younger “transplantation eligible” patients today is to use combination induction therapies that offer a high percentage likelihood of rapid and deep response. Although still controversial, we thus concur with the belief that maximizing initial response will for the majority of patients translate into better long-term disease control and survival. Treatment should therefore, in our opinion, use all available drugs of known effectiveness during initial therapy with careful attention to management of toxicities in a manner that ensures planned delivery of the intended therapeutics. In other words, we do not favor therapeutic rationing (ie, saving drugs for later).

Although early clinical trial data are supportive of our opinion,3-8 confirmatory clinical trials using the best novel agents are not yet available. Ongoing randomized trials comparing lenalidomide/dexamethasone or bortezomib/dexamathasone versus bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in combination are ongoing and will directly address the value of combination therapies versus therapeutic rationing. Until such trial results become available, our recommendations to use combination therapies outside of clinical trials represent interpretation of available trial data, some unpublished, and our own clinical experience.

In patients with comorbidities who are ineligible for, or unwilling to, pursue multidrug combination therapies and/or high-dose therapy, a reasonable alternate goal of treatment is to seek the best continuous disease control with less emphasis on depth of response and more emphasis on obtaining adequate symptom relief while maintaining quality of life. In this situation, therapeutic layering (adding new drugs in patients not responding to initial therapy) may be more logical. We further think that treatment should be individualized both in respect to prognostic risk profile9 and adapted to meet the competing demands of comorbidities and age.

Although the reality of today\'s global economic climate dictates that a balance between benefit and costs will be required, we present here therapeutic strategies independent of pharmacoeconomic considerations, as the latter are often country-specific, variable, and likely to change as clinical trial data mature. Finally, given the continuous and rapid advances being obtained through active collaboration between academia, industry, foundations, and government agencies, it is strongly recommended that eligible patients be offered participation in clinical trials whenever feasible. Indeed, today in many countries where newer therapies are not yet approved, this may provide the only means of access to state-of-the-art regimens described in “Choice of inital drug therapy.”

When to treat

Although the activity of novel agents has advanced to the point that early interventions are now being explored in clinical trials for smoldering myeloma, there is still no evidence that early treatment will improve survival in asymptomatic and biochemically stable patients. A critical point is that up to 25% of smoldering myeloma patients will not require active treatment for 10 to 15 years, although the majority will indeed progress during that time.10 The clinician should therefore avoid treating asymptomatic and biochemically stable patients with active therapy, allowing current drug development efforts to mature to their maximal efficacy at a time when systemic treatment does become a necessity. Indeed, some data suggest that early intervention may only serve to identify those patients at early risk for progression,11 or worse, theoretically to select out more aggressive genetic subclones of myeloma.

Once diagnosed, however, we emphasize that smoldering myeloma patients require frequent monitoring to allow treatment to begin before end-organ damage is evident, with the use of certain supportive therapies, such as bisphosphonates for osteopenia, justified in selected patients.

What investigations should be performed at diagnosis

The tests that guide a decision to start and define treatment paths are those that contribute to an unequivocal diagnosis of symptomatic MM and can afford important prognostic information. The essential tests diagnostic of myeloma are well established. We recommend that, in addition to the classic CRAB measurements of calcium, renal function, hemoglobin level, and skeletal survey, the β2-microglobulin, albumin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be measured, as these latter tests impart prognostic significance.12-14 Investigations for the monoclonal protein (M) require both serum and urine (24-hour) samples, and today should include the serum-free light chain assay, which has become mandatory in nonsecretory or oligosecretory MM and is often the first marker of response and progression.15 Serum-free light chain is also of value in solitary plasmacytoma, amyloidosis, and initial evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance to predict risk of progression to symptomatic MM.16

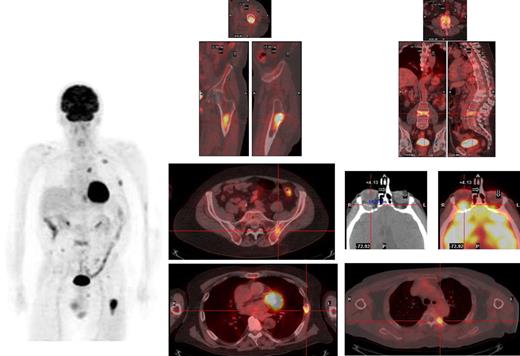

Sufficient (usually at least 5 mL) bone marrow (BM) should be obtained, not only for morphology but also for fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of key genetic events; this latter technique must be performed either in purified plasma cells or in combination with immunofluorescent detection of light chain restricted plasma cells (cIg-FISH) for t(4;14), t(14;16) and deletion of 17p, as these abnormalities identify high-risk disease.17 Metaphase cytogenetics should also be garnered when possible; the use of standard metaphase cytogenetics is often of low yield, but when positive for hypodiploidy, deletion of chromosome 13 or complex karyotype, with the exception of hyperdiploidy, imparts a particularly poor prognosis.18 Suggested genetic testing of patients is highlighted in Table 1. Finally, although the conventional skeletal survey remains the standard method for evaluation of bone lesions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive and is recommended to exclude spinal cord compression, soft tissue mass in a localized painful area or for assessing BM involvement in patients with solitary plasmacytoma and smoldering myeloma.19 The role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is less well defined in MM but can be useful for detecting extramedullary disease, unsuspected bone lesions, and evaluating patients with plasmacytoma as well as nonsecretory or oligosecretory MM.20-22 We have in our early experience found PET-CT to be of significant interest in many patients, providing reassurance when negative in smoldering disease and often revealing a previously unappreciated extent of disease in higher-risk patients (Figure 1).

Genetic tests to be performed in myeloma patients at diagnosis

| Essential tests for all patients . | Desirable tests . | Investigational tests for trials . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Essential tests for all patients . | Desirable tests . | Investigational tests for trials . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

FISH indicates fluorescent in situ hybridizaton; and aCGH/SNP, array comparative genomic hybridization/single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Myeloma deposits are identified by PET-CT in a relapsing patient in the left femur, ribs, thoracic and lumbar spine, and left iliac crest, and a previously unsuspected extramedullary lesion is identified behind the left orbit.

Myeloma deposits are identified by PET-CT in a relapsing patient in the left femur, ribs, thoracic and lumbar spine, and left iliac crest, and a previously unsuspected extramedullary lesion is identified behind the left orbit.

Durable complete response is a desirable endpoint

There is a growing body of evidence showing an association between depth of response to therapy and improved long-term outcomes, including progressive-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), in MM patients.3,5,8,23-27 Using conventional chemotherapy, it has been shown that there is a correlation between response before and after transplantation and that the quality of response after transplantation has a marked impact on outcome.8,27 Importantly, however, studies suggest that if a patient achieves a complete response (CR), this must be durable and that the duration of CR (rather than obtaining CR per se) is the best predictor of OS.28 Furthermore, although obtaining a durable CR is of apparent statistical value for the majority of MM patients, there are some subgroups (usually identifiable only after initial therapy has been completed) in which the value of initially obtaining a CR in predicting long-term outcome is more questionable. These subgroups include the high-risk group of rapidly responding, but early relapsing patients (typically defined by poor risk genetics), those more indolent myelomas that revert to an “monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance like” profile after therapy and those myeloma patients (increasingly uncommon) with stable nonprogressive disease after induction therapy. At present, our ability to accurately predict who these persons are a priori and before treatment is initiated remains limited. Pragmatically then, one must still start with maximal response, including a high expectancy of CR, as a goal.

Trial data and our recommendations in the next section use current definitions of CR, but an important caveat for consideration is that these definitions are suboptimal because a CR is currently based on the relatively insensitive criteria of the disappearance of the M-protein by immunofixation, the presence of less than 5% plasma cells in the BM and complete disappearance of any extra-osseous plasmacytoma.29 Even with the incorporation of new criteria such as the absence of clonal plasma cells by immunohistochemistry to define stringent complete remission, experience suggests that these tests may still have low relative sensitivity. To further improve the assessment of treatment efficacy, more sensitive tools are required going forward and will be explored in clinical trials both at the BM level (such as multiparametric flow cytometry26 ) and outside of the BM (eg, imaging techniques, such as MRI or PET-CT30 ). In addition, when assessing CR, MRI defined lesions may take as many as 18 to 24 months to normalize.

Choice of initial drug therapy

Although success and long-term remission have been achieved in many transplantation-eligible patients using limited treatment regimens, such as thalidomide/dexamethasone,31 bortezomib/dexamethasone,32,33 and lenalidomide/dexamethasone,34 complete and very good partial response (VGPR) rates can be substantially increased by combining these various drugs in triplets or even using 4 drugs together. Preliminary results from ongoing phase 3 randomized trials show improved initial response rates and increased frequency of CR after induction therapy in patients randomized to bortezomib and dexamethasone versus VAD chemotherapy, and in patients randomized to bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone versus thalidomide and dexamethasone alone. These initial higher quality responses translate into a higher frequency of CR after transplantation and at least in preliminary reports improved PFS. Because durable CR and PFS appear to be valuable surrogates for long-term outcome and an important platform for better disease control, we therefore favor multiple drug, combination therapies be applied in younger patients able to tolerate potential toxicities and pursue high-dose therapy approaches.

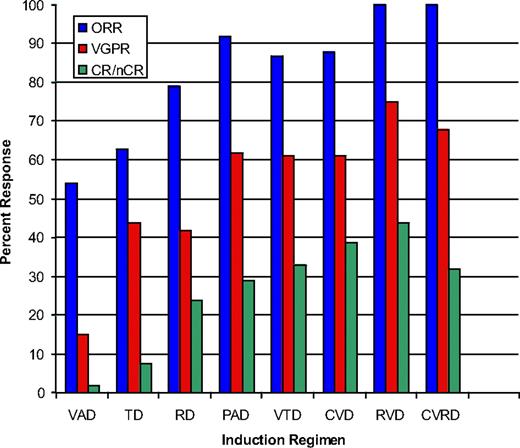

The earliest reports of triplet therapies came from the combination of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD),35 and the encouraging results have now been replicated using lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD),36 liposomal doxorubicin, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVD),37 and cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CVD)38 as examples. Response rates to these regimens are highlighted in Figure 2. A note of caution is that many of these studies are based on relatively small numbers of patients at single, or limited numbers, of centers, but cumulatively the message is consistent, with frequent, rapid, and deep responses seen. Although each of these regimens has shown high activity, it seems probable that combining all active drug classes will prove of value; thus, current clinical trials exploring 4-drug combinations (CVRD,41 VRDD, CVDD) are under way, although the impact of toxicity is a key consideration.

The overall, more than VGPR and nCR/CR rates for a selection of phase 2 and phase 3 trials incorporating novel agents. A continuous improvement in response is seen with the combination of newer agents. A cautionary note is that many of these are small single-center experiences, and evidence that early responses translate into longer-term survival is not yet available. References for these trials are as follows: VAD,39 TD,31 RD,40 PAD,37 VTD,6 CVD,38 RVD,36 and CVRD.39

The overall, more than VGPR and nCR/CR rates for a selection of phase 2 and phase 3 trials incorporating novel agents. A continuous improvement in response is seen with the combination of newer agents. A cautionary note is that many of these are small single-center experiences, and evidence that early responses translate into longer-term survival is not yet available. References for these trials are as follows: VAD,39 TD,31 RD,40 PAD,37 VTD,6 CVD,38 RVD,36 and CVRD.39

Although final randomized trial data are still awaited using these regimens, the success of PAD,42 VTD,6 of melphalan, prednisone, and bortezomib in elderly patients,7 and the promising results of Total Therapy 3 (TT3),4 using all active agents early in treatment, bode well and we think are probably reproduced using the 3- or 4-drug cocktails described above. The TT34 program based on VDT-PACE induction has in particular shown impressive results with 4-year event-free survival of 78% and sustained CR at 4 years in 87% of patients initially achieving a CR. Nevertheless, use of conventional chemotherapy drugs, including etoposide and cisplatinum, as part of an induction platform does not seem to have produced a significant response or survival advantage based on recent phase 3 trial data,32 and we think that the benefits of a second transplantation may only be evident in a subset of patients (see sections on transplantation below). Thus, while final reports from trials are still pending, we do not currently use etoposide and cisplatinum and routine tandem transplantation in our own practices, preferring a more individualized approach based on genetic risk balanced with patient tolerance of therapy and initial response to induction.

Although response rates are clearly improved with new drug cocktails, proving a consequent OS advantage is difficult and especially challenging given the large numbers of patients and the long duration of follow-up required.43 Clinical studies with OS as an endpoint are further complicated by the availability and constantly changing nature of effective salvage therapies. Thus, based upon response rates, depth of response achieved, and PFS as surrogates 3-drug cocktails are currently the modality of choice in our practices, with use of RVD, CVD, or VTD as the most commonly chosen regimens outside of clinical trials. In many countries, similar regimens are available only in a clinical trial setting; thus, early referral to a specialized center able to deliver novel drugs in combination may be desirable. Care must be taken to carefully manage the supportive care elements that go with such regimens to minimize side effects and ensure durable benefit. Finally, there appears to be no future role for the continued use of VAD-based regimens or single-agent dexamethasone, and arguably even thalidomide and dexamethasone, which may be inadequate as these regimens have been shown to be suboptimal therapies as emphasized in recent trials.6,31,32,37 Refractory or progressive disease is now uncommon when using multidrug combinations with overall response rates (more than partial response) exceeding 90% in almost all current studies. However, when presented with a truly refractory patient, timely referral for high-dose melphalan should be considered, as this group of patients may benefit from this approach.

An area of uncertainty is the dose of corticosteroids to use in induction. Although responses are faster and deeper with more dose-intense steroid use, OS does not seem improved by earlier introduction of high-dose dexamethasone, and such an approach may be inferior as it has a significantly higher risk of toxicity.40 Thus, we suggest using higher doses of dexamethasone only in patients in whom a rapid response is needed. We recommend higher-dose dexamethasone (such as 40 mg, days 1-4, 9-12, and 17-20) in those with life-threatening hypercalcemia, spinal cord compression, incipient renal failure, or extensive pain, but lower weekly dosing should be pursued in patients who do not require rapid tumor reduction, and particularly those in whom multidrug cocktails are being used, which allows a “steroid-sparing” approach to be used.

How much treatment before stem cell transplantation

For the patient eligible for transplantation, our practice is usually to proceed to autologous stem cell collection and transplantation after 4 to 6 cycles of induction therapy. However, because our stated goal of therapy is to maximize the depth and duration of remission, induction therapy can be continued in some patients for as long as the patient is responding and tolerating therapy. We view the optimal contribution of high-dose melphalan and stem cell transplantation to be as a consolidation of remission after obtaining the best possible response to frontline treatment.

One controversial area is what to do if the patient has already achieved a CR before transplantation. In this decision, the role of continued chemotherapy treatment versus proceeding to transplantation is less clear and an area of active research. For now, and until clinical trials prove otherwise, we generally prefer to proceed to transplantation in most patients and even if conventional CR is achieved by induction therapy, but the option to defer can be discussed with the patient. This reflects our belief that current measures of CR are insufficiently sensitive and residual disease is in many, if not all, patients present but below the level of detection.26 If the patient is still not in a CR or near CR after transplantation, additional consolidation/maintenance therapy, including, but not restricted to a second autologous transplantation can be considered.

The role of transplantation

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has been shown in randomized trials to be of value to patients in helping achieve or consolidating CR44-46 and is thus used in the majority of our patients eligible and willing to undergo this procedure. New trials will address whether or not transplantation remains useful in the era of novel drugs; but until proven otherwise, we think it is likely to still be of value in achieving a higher frequency and depth of CR in patients, and thus contribute to prolonged survival. Upper age limits vary widely from center to center and country to country, but in general the overall health of the patient rather than a specific chronologic age is probably most relevant. Earlier studies demonstrated an advantage to a second or tandem transplantation only in patients who do not obtain at least a VGPR after the first procedure.45,47 However, because CR rates are now achieved more than 50% to 70% of the time with effective induction therapies combined with single ASCT,6,32,38 and because responses may be further enhanced by posttransplantation consolidation/maintenance therapies, there is less frequently the need to perform a second (or tandem) transplantation early in the disease course. The choice for maintenance therapies that can be used after transplantation48,49 will be discussed in the next section.

The timing of ASCT is also an area of active research. Patients are usually more fit for intensive therapy early in the course of the disease, but prior studies using conventional chemotherapy as induction demonstrated that a delayed ASCT had no adverse impact on OS and is feasible as part of salvage therapy in first relapse.50,51 Randomized trials to better define populations served by this approach are planned, and a delayed transplantation may be considered in some patients doing well on induction drugs, obtaining an excellent response and who are not inclined to pursue the social and quality of life disruptions entailed by high-dose melphalan-based therapy.

Allogeneic transplantation should infrequently be performed outside of clinical trials, as the risk of morbidity and early mortality of even nonmyeloablative transplantations is considerable and thus not acceptable for most patients in the current era of longer survival.51-53 In very young patients, particularly those who experience early relapse or with very high risk features at diagnosis, this therapeutic strategy may, however, offer some hope of long-term disease control and can be considered. Suffice it to say that the number of patients undergoing allogeneic transplantation at our centers remains low and it is not often performed outside of the clinical trial setting.

Consolidation and maintenance therapy after transplantation

Three separate phase 3 studies found thalidomide maintenance to improve overall survival (Table 2).3,48,49 Despite these findings, thalidomide is not being routinely used for maintenance in many centers, presumably reflecting concerns about cumulative toxicity. Lenalidomide may offer the same advantages with less toxicity, and large randomized trials are now addressing its role in the posttransplantation setting. It has become our practice to use maintenance routinely when patients have not achieved a CR after stem cell transplantation or when genetic risk markers suggest a very high risk of early relapse.9 In our opinion, either thalidomide or lenalidomide probably proves suitable. There are insufficient data on bortezomib maintenance on which to form an opinion although trials are under way.42 It is not known how long maintenance should be continued, but we generally use it indefinitely and taper dosing for tolerance. Anticoagulation is not a requirement in the maintenance setting, but is recommended.

Phase 3 trials of thalidomide containing maintenance after ASCT

| Study . | Group . | PFS . | OS . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spencer et al48 | Control | 23 | 75 | At 3 years |

| Thalidomide Prednisone | 42 | 86 | ||

| Barlogie et al3 | Control | 20 | 44 | At 8 years |

| Thalidomide | 45 | 57 | ||

| Attal et al49 | Control | 36 | 77 | At 3 years after randomization for EFS, 4 years after diagnosis for OS |

| Thalidomide | 52 | 87 |

| Study . | Group . | PFS . | OS . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spencer et al48 | Control | 23 | 75 | At 3 years |

| Thalidomide Prednisone | 42 | 86 | ||

| Barlogie et al3 | Control | 20 | 44 | At 8 years |

| Thalidomide | 45 | 57 | ||

| Attal et al49 | Control | 36 | 77 | At 3 years after randomization for EFS, 4 years after diagnosis for OS |

| Thalidomide | 52 | 87 |

EFS indicates event-free survival, and OS, overall survival.

Prognosis and genetics

Extremes of genetic subtypes of MM require special attention. Genetically high-risk patients, defined by the presence by FISH of t(4;14) with an associated high β-2-microglobulin, a t(14;16), a deletion of p53 on chromosome 17, by the presence of deletion of chromosome 13 or hypodiploidy by conventional cytogenetics are one such class (Table 3).9 In such patients, bortezomib-based treatments appear to be of some value in ameliorating genetic risk,4,7,56 although long-term follow-up is still required before a firm conclusion can be drawn on this topic. The value added by high-dose melphalan and transplantation is much less certain in these patients, as event-free survival in high genetic risk patients were very short after transplantation in the era before novel drugs became available.57,58 Indeed, very-high-risk patients continue to do poorly compared with those with low-risk genetics even with tandem transplantation procedures.2 Of some encouragement, a significant improvement in survival for high-risk patients has been seen when novel drugs, such as thalidomide and bortezomib, are added to tandem transplantation as reported in the Total Therapy 2 successor TT3.4 Despite this, high-risk patients remain substantially challenging, and longer-term induction therapy to maximal response followed by indefinite maintenance could be used as an alternative to early transplantation.59 In contrast, patients with hyperdiploid myeloma and absence of other poor prognosis factors, such as elevated LDH or β-2 microglobulin, appear to have a generally good prognosis and seem to do well on relatively simple regimens, such as lenalidomide and dexamethasone, and this approach may be suitable for those standard-risk patients who do not wish more aggressive therapy.59

Patients not wishing or not suitable for high-dose melphalan and transplantation

In the patient who does not want transplantation through choice, then induction therapy (such as VTD, RVD, or CVD) can be prolonged to maximal response as an alternative to transplantation with maintenance considered, particularly in those not achieving CR or at high risk for early relapse. Alternative regimens in younger patients who do not plan to receive a transplantation could use alkylating agents in combinations, such as melphalan, prednisone, and bortezomib or cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone,60 either of which could also be considered based on the availability of drugs. Less aggressive treatment with, for example, lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, may be appropriate for patients not requiring a very rapid response to initial therapy and who are at reduced risk of early relapse based on standard-risk clinical features (eg, low β-2 microgloblin, low LDH, absence of high-risk genetic features).

In patients with significant comorbidities precluding transplantation, combination therapies may be challenging to administer, and in such patients we more often opt for an initially less toxic and invasive approach to treatment with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone being one suitable regimen.34 In these cases, the goal would be to obtain the best possible response while managing toxicities. The optimal longevity of therapy under these conditions is not known, so generally we treat until intolerance of therapy for any reason, or progression.

Issues around mobilization of stem cells

After current induction therapies, stem cells can be collected in numbers adequate to perform up to 2 ASCTs. Nevertheless, in patients who have received prior melphalan61 or prolonged treatment with lenalidomide,62,63 failure to collect has emerged as a concern, and in such patients alternative collection strategies can be considered. We therefore avoid melphalan and usually limit the number of prior cycles with lenalidomide-based therapy (eg, up to 4 cycles) before collection, and use mobilization regimens in those patients who have received more than 4 cycles that incorporate cyclophosphamide64 or plerixafor.65 With such measures, the success of collection is higher and almost all patients receiving prior lenalidomide can collect sufficient cells in support of at least one single intensification with ASCT using high-dose melphalan.39

Supportive care

Although easy to overlook during a busy clinic, modern MM therapy requires expert attention to supportive care. This involves careful patient education about the probable side effects of each drug and the drug combinations being used, and the supportive care adjustments required. Supportive care can be categorized into those measures required for all patients and those that address specific drugs.

For every patient, an emphasis on adequate hydration, low impact exercise, avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs, pain control, and chemotherapy education should be accompanied by use of a bisphosphonate and other measures appropriate for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis or osteolytic disease, when present. Consideration of the long-term consequences of bisphosphonate use should be made,66 with appropriate and frequent dental evaluation and care recommended. Hematopoietic growth factors can, and should, be used in anemic or neutropenic patients. Attention regarding infection and infection prophylaxis is critical. The use of a quinolone or other prophylactic antibiotic during the first few months of therapy seems to be important in patients receiving higher doses of corticosteroids. Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination is appropriate, even if unlikely to provide complete humoral immunity. Herpes zoster prophylaxis with acyclovir should be used in all patients receiving a proteasome inhibitor and in the post-ASCT setting. Antifungal prophylaxis can be used in more intensive approaches and especially with steroids, in particular high-dose dexamethasone, with prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii also prudent.

Other specific measures include the risks and management of neuropathy,67 low blood counts, and diarrhea common to the proteasome inhibitors and long-term lenalidomide use. The cornerstone of managing neuropathy associated with bortezomib is dose-reduction and schedule change, as severe neuropathy is potentially avoidable and most neuropathies partially reversible with careful attention to dose, schedule, and therapy change where required.68 Recent evidence suggests that once weekly dosing may be helpful in this regard, although efficacy may be compromised.69

Neuropathy and constipation with thalidomide or low blood counts with lenalidomide are well recognized and can again be managed by dose adjustment, symptom management and growth factor support.70 Thrombosis is relatively common when thalidomide or lenalidomide is used with steroids, and is particularly frequent when treating newly diagnosed patients and when using these drugs in concert with an anthracycline or alkylator. Thromboprophylaxis with immunomodulatory agents is therefore mandatory when used in combination therapy during induction. For patients at low risk of thrombosis receiving lenalidomide or thalidomide with daily aspirin (325 or 81 mg), deep vein thrombosis rates are low, but still approximately 5% to 10%. For patients at higher deep vein thrombosis risk resulting from other factors, such as prior history, immobility, use of anthracyclines, and smoking, then therapeutic anticoagulation using either low molecular weight heparin or coumadin is recommended.71 Patients on thalidomide or lenalidomide should also be monitored for hypothyroidism. Weight gain, insomnia, hyperglycemia, gastric irritation, and anxiety may all need to be countered in patients receiving steroids. Some recently emerging literature suggests that avoidance of certain natural herbal supplements (eg, green tea in bortezomib-treated patients) is prudent,72 as there may be antagonism.

It is worth remembering that amyloidosis is a potential complication in all myeloma patients and is a possible contributing factor in patients presenting with hypotension, nephrotic range proteinuria, persistent diarrhea, neuropathy, heart failure, and fatigue.

Practical considerations

In the United States, lenalidomide is not yet Food and Drug Administration–approved in newly diagnosed patients, and its use is therefore “off label” but readily accessible. In many other countries, access to lenalidomide and even bortezomib is more restricted. Under such circumstances, the choice of initial therapy will be dictated by the realities of availability. For that reason, clinical trials may offer the best option for many patients; thus, referral to a center with access to novel agents through trial participation is highly recommended. Outside of a trial setting, cyclophosphamide, anthracyclines, and steroids in younger patients are good choices for therapy to which we would encourage the addition of thalidomide, bortezomib, or lenalidomide as available.

In countries in which novel agents have not yet been approved for up-front treatment, we suggest the use of the best available conventional induction regimens (eg, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, for 4-6 cycles) followed by ASCT; nevertheless, if after the first initial 3 or 4 cycles, the patient has achieved less than partial response, the use of a salvage therapy based on novel agents (eg, VD, RD, VTD, or RVD) before transplantation is recommended.

In conclusion, we recommend that in patients with newly diagnosed MM active treatment should be reserved until symptoms and/or end-organ dysfunction are present or imminent. When treatment begins, the goal is a rapid and high quality response with postinduction consolidation and maintenance to sustain a durable CR being optimal. In pursuit of this goal, 3 drug triplets (VTD, RVD, and CVD) are examples of highly active new combinations that can be used, with high response rates and frequent CR. We think that this approach will translate into longer survival and will be validated as clinical trials mature. For the majority of younger patients, consolidation with high-dose melphalan and ASCT after 4 to 6 cycles of induction therapy is favored. For patients failing to achieve CR after transplantation or with high-risk genetic features, routine maintenance therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide should be considered. The role of bortezomib in maintenance remains to be defined but preliminary results are promising. The prognostic risk profile of a patient should be determined, using both clinical and genetic features of the MM. As high-risk patients may gain only modest benefit from ASCT alone, a consolidation/maintenance strategy, eg, thalidomide or lenalidomide with or without bortezomib as postinduction therapy, could be used as an alternative. For patients who do not wish to pursue high-dose therapy, with standard genetic risk and particularly patients who are unfit to pursue ASCT, a durable response may be achieved using less toxic treatment approaches, such as low-dose dexamethasone with lenalidomide or bortezomib. In all patients, careful attention to supportive care is critical to avoid early complications that may compromise subsequent therapeutic outcome. Therapy must be individualized with geography, out-of-pocket cost, drug availability, social considerations (such as caregivers at home), comorbidities, and patient preference all being considered, as each may influence treatment choice. Fortunately, today such choice exists with many potent regimens available. Moreover, large phase 3 trials are under way in younger MM patients to determine the best approach, and should be strongly considered for all patients.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K.S., P.G.R., and J.F.S.-M. were fully involved in writing this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.G.R. is on advisory boards for Millennium, Johnson and Johnson, and Celgene. A.K.S. is a consultant for Millennium and Proteolix, has received research support from Millennium, is on advisory boards for Celgene and Genzyme, and has received honoraria from Ortho Biotech. J.F.S.-M. is on advisory boards for Millennium, Celgene, and Janssen-Cilag.

Correspondence: A. Keith Stewart, CRB3-008, Mayo Clinic Arizona, 13400 East Shea Blvd, Scottsdale, AZ 85259; e-mail: stewart.keith@mayo.edu.