Abstract

Abstract 797

Epidemics of influenza A virus strains have been associated with a mortality rate of 0.1% and hospitalization of approximately 200,000 people per year in the United States. The recent pandemic of swine-origin H1N1 has further emphasized the need to protect the population. Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) are particularly vulnerable to flu infection from altered humoral and cellular immunity from the disease as well as from the immunosuppressive chemotherapies, corticosteroids and radiation frequently used for treatment. In particular, high dose melphalan and ASCT, a common and efficacious treatment as part of first-line or salvage therapy for MM, is associated with post-ASCT immune suppression by virtue of low T-cell numbers, poor T-cell function and immune paresis. Despite anti-infection vaccination after ASCT, pneumococcal pneumonia and influenza are common. In an attempt to improve this outcome we previously showed that adoptive transfer of in-vivo PCV vaccine-primed and ex-vivo (anti-CD3/anti-CD28) co-stimulated autologous T cells (aT-cells) early (within 14 days) post-ASCT increased CD4 and CD8 T cell counts and induced pneumococcal conjugate vaccine-directed T and B-cell responses [Rapoport et al, Nature Medicine, 2005]. Patients who did not receive pre-collection vaccination did not show this response despite infusion of co-stimulated T-cells and post-ASCT vaccination. In the current clinical trial we investigated whether pre-harvest flu vaccination would result in a similar improvement in immunity.

We performed a randomized open-label single center study of two influenza vaccine schedules for patients with high-risk MM responding after conventional induction therapy. Of 21 patients enrolled, 11 were randomly assigned to Group X and received pre- and d+14 post-transplant flu vaccine with the commercially available influenza vaccine (Fluzone) produced by Aventis Pasteur. The 10 patients in Group Y received only post-transplant vaccination. All patients received T-cell harvest, high dose melphalan and ASCT and aT-cell infusion. Immunological assessment (T-cell and B-cell subsets, T-cell repertoire, T-ELISPOT, CFSE-CBC, antibody HAI, B-ELISPOT) was conducted d+60, 100 and 180. The primary study endpoint is the immune response to influenza as measured by the serotype-specific influenza antibody response on day 100 using a standard hemagglutination inhibition assay (HAI) optimized for the vaccine administered each year.

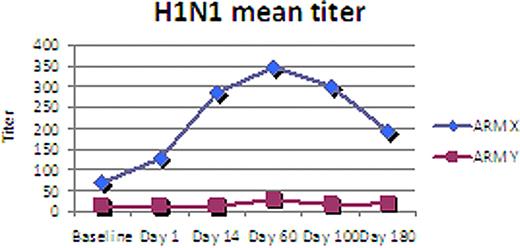

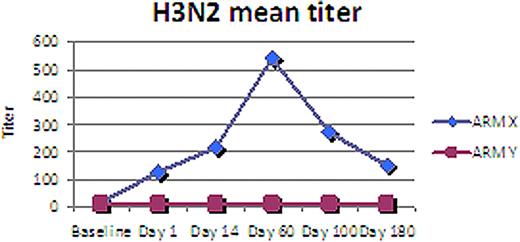

The median age was 55 (range 37-68), 13 M, 8 F, 18 Caucasian, 2 African American, 1 Hispanic, IgG 57%, IgA 33%, light chain 10%. With a median follow-up of 1 year, 86% (18/21) patients are alive with 48% (10/21) alive in remission. No difference in these parameters was seen between both Groups. HAI titers, however were higher at all three time points (d+60, 100, 180) for Group X when compared to Group Y both for H3N2 (p= 0.04) and for H1N1 (p=0.07). HAI titers for Group Y remained near baseline throughout all time points while Group X peaked day 60 and remained elevated day 180. Analysis of other immune assessment is ongoing and will be presented.

Preliminary analysis of this randomized trial of flu vaccine schedule for MM patients undergoing ASCT suggests superior flu immune reconstitution when vaccine is administered to prime autologous T-cells prior ASCT and aT-cell infusion. This result adds to our observation that an approach of vaccine priming and co-stimulated autologous T-cell infusion after high dose melphalan and ASCT for MM augments an otherwise poor response in this patient population to pneumococcal and influenza vaccination. Investigation of this approach as a platform for anti-myeloma immune therapy is ongoing.

June:University of Pennsylvania: Patents & Royalties.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal