Abstract

Extravasation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) to the site of inflammation precedes a second wave of emigrating monocytes. That these events are causally connected has been established a long time ago. However, we are now just beginning to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying this cellular switch, which has become even more complex considering the emergence of monocyte subsets, which are affected differently by signals generated from PMNs. PMN granule proteins induce adhesion as well as emigration of inflammatory monocytes to the site of inflammation involving β2-integrins and formyl-peptide receptors. Furthermore, modification of the chemokine network by PMNs and their granule proteins creates a milieu favoring extravasation of inflammatory monocytes. Finally, emigrated PMNs rapidly undergo apoptosis, leading to the discharge of lysophosphatidylcholine, which attracts monocytes via G2A receptors. The net effect of these mechanisms is the accumulation of inflammatory monocytes, thus promoting proinflammatory events, such as release of inflammation-sustaining cytokines and reactive oxygen species. As targeting PMNs without causing serious side effects seems futile, it may be more promising to aim at interfering with subsequent PMN-driven proinflammatory events.

Causal role of neutrophils in monocyte recruitment

The sequence of phagocyte recruitment to the site of inflammation comprises an initial extravasation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) followed by a subsequent emigration of monocytes. Rebuck and Crowley provided the early evidence for such sequence of events in a human recruitment model.1 One explanation for this recruitment pattern could be the higher frequency of PMNs in peripheral blood. Another explanation may be provided by the differential use of chemokines and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Adhesion and emigration of PMNs depend very much on the presence of CD62L, CD62P, β2-integrins, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), ICAM-2, as well as chemotactic agents such as C5a, leukotriene B4, platelet activating factor, or interleukin-8 (IL-8), many of which are either preformed and rapidly exteriorized by PMNs, mast cells, and endothelial cells or rapidly produced by enzymatic cleavage. In contrast, monocytes tend to use CD62E, β1-integrins, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), requiring de novo synthesis and therefore the sequence of leukocyte recruitment may not be causally connected.2

This, however, was contradicted by Ward, who provided the first evidence that there is a causal link between the initial PMN extravasation and the later emigration of monocytes.3 Lysates of PMNs were shown to exert chemotactic activity on monocytes, suggesting an important role for preformed stores of cellular mediators in launching monocyte extravasation. Further support for such causal connection stems from patients with functional PMN deficits. Gallin et al found that the PMN lysate of patients suffering from specific granule deficiency lacks its chemotactic effect on monocytes.4 PMNs from these patients lack granule proteins such as human neutrophil peptides (HNPs, α-defensins) and human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 (proform of LL-37),5 indicating an importance of these granule components in attracting monocytes. Patients suffering from the rare Chédiak-Higashi syndrome display not only reduced PMN degranulation, but also impaired monocyte chemotaxis.6 Finally, neutropenic septic patients have lower numbers of monocytes and macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids.7 However, it has been difficult to standardize conditions and to dissect underlying mechanisms in human studies, and therefore murine models have been applied to study the interrelation between emigration of PMNs and monocytes. cEBP−/− mice displaying the murine specific granule deficiency model were shown to have deficient monocyte emigration.8 Mice with the beige mutation are the equivalent of the human Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. These mice exhibit reduced chemokine contents in lung homogenates as well as reduced monocyte recruitment.9 Dipeptidyl peptidase I−/− mice are deficient in mature serine proteases in PMNs, therefore representing the homologue of the human Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Monocyte emigration is severely impaired in these mice.10 Clear evidence for the involvement of PMNs in the extravasation of monocytes is also obtained from murine models of neutropenia. Depletion of PMNs by injection of antibodies to Gr1 or Ly6G has been shown to selectively remove PMNs. Using such an approach it was demonstrated that neutropenic mice exhibit impaired monocyte recruitment in acute and chronic models as well as infectious and noninfectious models, thus indicating that the PMN-monocyte axis is indeed important in the physiology of the resolution of inflammation. Table 1 offers an overview of models showing the affection of monocyte recruitment in several models of neutropenia.

Neutropenia reduces monocyte recruitment

| Stimulus . | Organ . | Observation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western diet of atherosclerotic mouse | Aorta | Reduced number of macrophages in aortic roots | 11 |

| PAF, L monocytogenes | Air pouch | Reduced emigration of inflammatory monocytes reconstituted by local application of PMN supernatant | 10 |

| LPS | Lung | Reduced monocyte emigration in response to LPS-inhalation in rats | 12 |

| L monocytogenes | Peritoneum | Reduced macrophage numbers and bacterial clearance | 13 |

| Carrageenan | Air pouch | Reduced monocyte infiltration and soluble IL-6 receptor concentrations in the air pouch of neutropenic mice | 14 |

| Polyacrylamide | Skin | Reduced monocyte infiltration into skin granulomas, which was restored by local application of PMN supernatant | 15 |

| Neurotropic JHM strain of mouse hepatitis virus | Brain | Reduced macrophage recruitment over 6 days post infection | 16 |

| Stimulus . | Organ . | Observation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western diet of atherosclerotic mouse | Aorta | Reduced number of macrophages in aortic roots | 11 |

| PAF, L monocytogenes | Air pouch | Reduced emigration of inflammatory monocytes reconstituted by local application of PMN supernatant | 10 |

| LPS | Lung | Reduced monocyte emigration in response to LPS-inhalation in rats | 12 |

| L monocytogenes | Peritoneum | Reduced macrophage numbers and bacterial clearance | 13 |

| Carrageenan | Air pouch | Reduced monocyte infiltration and soluble IL-6 receptor concentrations in the air pouch of neutropenic mice | 14 |

| Polyacrylamide | Skin | Reduced monocyte infiltration into skin granulomas, which was restored by local application of PMN supernatant | 15 |

| Neurotropic JHM strain of mouse hepatitis virus | Brain | Reduced macrophage recruitment over 6 days post infection | 16 |

Thus, it is established that PMNs contribute to the launch of monocyte recruitment. Recent advances in monocyte biology providing evidence for the existence of several monocyte subsets with distinct functions and recruitment behavior call for critical review of the mechanisms of PMN-mediated monocyte emigration. Due to the lack of suitable recruitment assays in humans, mechanistic insight into the causal interrelation between PMNs and monocyte extravasation is primarily inferred from murine studies. As recruitment and function of monocyte subsets in mice may differ from those in humans, one has to be cautious when transferring those mechanisms to human physiology.

Mechanisms of recruitment of monocyte subclasses

The classical monocyte extravasation cascade involves a series of sequential molecular interactions between monocytes and endothelial cells. Selectins initiate the recruitment process by allowing the monocyte to transiently interact with the endothelium. Rolling monocytes are gradually slowed down, thus enabling the monocyte to recognize endothelial-bound chemokine and chemotactic agents such as platelet activating factor and leukotriene B4. Subsequent monocyte activation results in integrin activation enabling firm adhesion to endothelial cell adhesion molecules. Chemokines subsequently lead to the induction of active, cytoskeleton-driven transendothelial migration and extravasation.17-19

This simplified model of monocyte recruitment becomes however much more difficult when taking the heterogeneity of monocytes into account. Monocyte subsets are not just phenotypically different, thus using alternate sets of cell adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors, but also exhibit different functions and are recruited at different time points after initiation of inflammation. In the human system, classical CD14+CD16− monocytes produce lower amounts of proinflammatory cytokines but contribute more effectively to bacterial clearance by phagocytosis compared with nonclassical monocytes.20-22 In contrast, nonclassical CD14loCD16+ monocytes are more potent in presenting antigens.23 Whereas migration of CD14+CD16− monocytes into sites of inflammation has been shown to be governed by CCL2,24 CD14loCD16+ failed to migrate in response CCL2, consistent with the absence of CCR2 on these cells.25 Studies by Ancuta et al showed that the CD14loCD16+ monocytes will migrate in response to CX3CL1 and CXCL12.26 It was also noted, however, that the CD14loCD16+ monocytes adhere to activated endothelium more strongly,27 and this was suggested to be mediated in part by CX3CL1 expressed on the cell surface of the endothelial cells. Such firm adherence to CX3CL1-expressing endothelial cells did lead to a reduced transmigration in response to CX3CL1 in vitro.

Although it has been known for many years that human peripheral blood monocytes are a heterogeneous population of leukocytes, distinguishable by the expression of CD14 and CD16, this has just recently also been confirmed in the murine circulation. Geissmann et al described the existence of at least 2 different monocyte subsets, which can be distinguished by their expression levels of Ly-6C (or Gr1) and of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CX3CR1.28 Murine CX3CR1loCCR2+Gr1+ monocytes share morphologic characteristics and chemokine receptor expression patterns with the classical human CD14hiCD16−, whereas CX3CR1hiCCR2−Gr1− are thought to resemble the phenotype of nonclassical human CD14loCD16+ monocytes. Whereas human CD14hiCD16− monocytes produce IL-10 rather than tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1 in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in vitro, murine CX3CR1loCCR2+Gr1+ monocytes efficiently produce proinflammatory cytokines.29,30 In addition, CD14hiCD16− monocytes account for about 90% of monocytes in peripheral blood, whereas the suggested murine correlate makes up for 50% of murine monocytes.

Murine monocyte subsets use different mechanisms for extravasation and also possibly exert different functions, with Gr1+ monocytes termed “inflammatory” and Gr1− as “resident” monocytes accordingly. Because Gr1+ monocytes express CCR2, a molecule well known to be involved in inflammatory monocyte recruitment,31 it was proposed that Gr1+ monocytes are rapidly recruited to sites of inflammation. Indeed, in typical models of acute inflammation, Gr1+ monocyte recruitment is critically dependent on CCR2,32,33 but not on CX3CR1.34,35 In addition to CCR2, CCR6/CCL20 is involved in the recruitment of Gr1+ monocytes.36,37

Less is known about the trafficking and fate of Gr1− monocytes. In contrast to Gr1+ monocytes, Gr1− monocytes migrate scarcely or not at all to inflamed tissue in mice, including the acutely inflamed peritoneum,26,38 or to skin after intracutaneous injection of latex beads, administration of vaccine formulations,37 or epicutaneous ultraviolet exposure.39 It has therefore been hypothesized that Gr1− monocytes may fulfill critical roles in replacing resident macrophages or dendritic cells in the steady state.28 It has further been suggested that the Gr1− monocytes use CX3CR1 to migrate into noninflamed tissue for replacing resident macrophages or dendritic cells, given their higher surface expression of CX3CR1 and the CX3CL1-dependent transendothelial migration of the corresponding human subset of CD16+ monocytes in vitro.26,28 However, the experimental evidence for the trafficking pattern and the potential role of Gr1− monocytes as precursors for resident tissue cells is rather limited. Just recently Auffray et al demonstrated that Gr1− monocytes patrol healthy tissue by long-range crawling on resting endothelium. This crawling depends on LFA-1 as well as CX3CR1.40 Functionally, the patrolling was thought to allow for rapid extravasation upon injury. However, further studies are needed to corroborate these findings and to elucidate the functional properties of this monocyte subset.

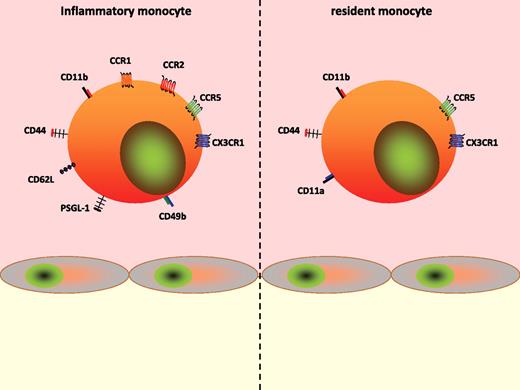

Although the involvement of selectins and cell adhesion molecules has traditionally been investigated for monocytes as such, recent data indicate distinct engagement patterns of these receptors for the monocyte subsets. An et al demonstrated that inflammatory monocytes express higher levels of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1, which was found to be crucially involved in the interaction of Gr1+ monocytes with the atherosclerotic endothelium.41 Although such an approach has not been applied for other adhesion molecules, it is to be expected that the expression pattern also determines the use of the respective molecule. Therefore it is noteworthy that inflammatory monocytes express higher amounts of CD62L and CD49b compared with resident monocytes, whereas the opposite is true for CD11a.42 No differences exist for CD44 and CD11b (Figure 1).

Phenotype of monocyte subsets. Inflammatory (left) and resident (right) monocytes differentially express cell adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors, thus implying alternate recruitment mechanisms.

Phenotype of monocyte subsets. Inflammatory (left) and resident (right) monocytes differentially express cell adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors, thus implying alternate recruitment mechanisms.

Contribution of PMN granule proteins to monocyte recruitment

Early experiments by Gallin et al pointed to the importance of ready-made PMN granule proteins in recruitment of monocytes.4 Granule proteins are stored in 4 distinct sets of granules (Table 2). Whereas rapidly mobilized secretory vesicles contain mainly receptors important for adhesion and recognition of foreign particles, tertiary granules released during transendothelial migration contain mainly proteases. Primary and secondary granules discharged from emigrated PMNs contain mainly antimicrobial polypeptides.43

Contents of neutrophil granule subsets

| . | Secretory vesicles . | Tertiary granules . | Secondary granules . | Primary granules . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release | PMN-EC interaction | Penetration of basement membrane | Extravascular tissue | Extravascular tissue |

| Receptors and membrane-bound proteins | FPR, CD14, CD16 β2-integrins, proteinase-3 | FPR, β2-integrins, TNF receptor | FPR, β2-integrins, laminin receptor, CD66, CD67 | CD63, CD68 |

| Proteins released into the surrounding | Azurocidin, albumin | MMP-9, lysozyme, arginase | Collagenase, LL-37, lysozyme, lactoferrin | Azurocidin, HNP1-3, cathepsin G, elastase, MPO, proteinase-3 |

| . | Secretory vesicles . | Tertiary granules . | Secondary granules . | Primary granules . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release | PMN-EC interaction | Penetration of basement membrane | Extravascular tissue | Extravascular tissue |

| Receptors and membrane-bound proteins | FPR, CD14, CD16 β2-integrins, proteinase-3 | FPR, β2-integrins, TNF receptor | FPR, β2-integrins, laminin receptor, CD66, CD67 | CD63, CD68 |

| Proteins released into the surrounding | Azurocidin, albumin | MMP-9, lysozyme, arginase | Collagenase, LL-37, lysozyme, lactoferrin | Azurocidin, HNP1-3, cathepsin G, elastase, MPO, proteinase-3 |

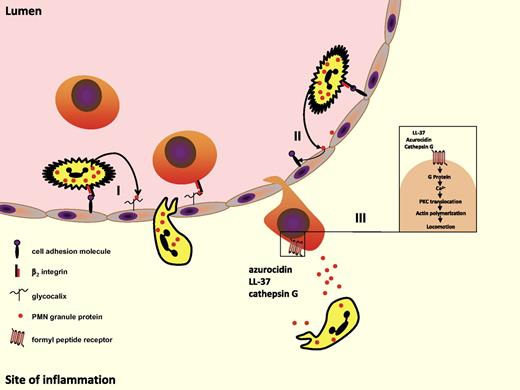

Adhesion of PMNs to the endothelial cells via β2-integrin ligation results in rapid release of secretory vesicles. Besides membrane-bound receptors, proteinase-3 and azurocidin (also known as heparin-binding protein or cationic antimicrobial protein 37) are the only proteins to reside within this granule compartment that are distributed into the surrounding upon granule mobilization. Although no receptors for either protein have yet been identified on endothelial cells, it was shown that the interaction of azurocidin and proteinase-3 with the endothelium results in the activation of the latter, signified by, for example, changes in transendothelial permeability.44-46 Azurocidin also activates endothelial protein kinase C47 and is rapidly internalized after the initial attachment to the endothelial cell. The latter mechanism may be important in preventing endothelial cell apoptosis,48 whereas the first may be important for the altered gene expression observed after exposure of endothelial cells to azurocidin. Lee et al have shown that azurocidin enhances the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, resulting in enhanced adhesion of human monocytes.49 Similarly, proteinase-3 induces expression of these 2 CAMs resulting in enhanced adhesion of PMNs and monocytes to isolated endothelial cells50 (Figure 2).

PMN granule proteins induce monocyte adhesion and recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. (I) Granule proteins discharged from adherent PMNs anchor on endothelial proteoglycan side chains. In this location, they are recognized by monocytes rolling along the endothelium. Subsequent monocyte activation allows for their firm adhesion. (II) Granule proteins activate endothelial cells to express cell adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 leading to enhanced monocyte adhesion. (III) Azuorcidin, LL-37, and cathepsin G released from emigrated PMNs induce extravasation of inflammatory monocytes by use of formyl peptide receptors.

PMN granule proteins induce monocyte adhesion and recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. (I) Granule proteins discharged from adherent PMNs anchor on endothelial proteoglycan side chains. In this location, they are recognized by monocytes rolling along the endothelium. Subsequent monocyte activation allows for their firm adhesion. (II) Granule proteins activate endothelial cells to express cell adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 leading to enhanced monocyte adhesion. (III) Azuorcidin, LL-37, and cathepsin G released from emigrated PMNs induce extravasation of inflammatory monocytes by use of formyl peptide receptors.

Both azurocidin and proteinase-3 are strongly positively charged and may therefore interact with the negatively charged endothelial proteoglycans. Thus, it is not surprising that azurocidin and proteinase-3 were found in endothelial location, an instance abrogated by blocking PMN adhesion. Immunohistochemical staining for azurocidin and proteinase-3 revealed their localization in human specimens in both acutely or chronically inflamed tissues. For example, azurocidin and proteinase-3 were demonstrated on the endothelial cell surface of atherosclerotic plaques as well as in lesions from Alzheimer patients.51,52 In this location, azurocidin is prone to activate monocytes and specifically induces their adhesion.53 This is in line with observations that fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated azurocidin binds to monocytes, but not lymphocytes, and to a lesser degree to PMNs.54,55 Unpublished data from our group (O.S., June 2009) indicate that the adhesion of inflammatory human monocytes to azurocidin is mediated by involvement of β2-integrin activation. Similarly, leukocyte adhesion to proteinase-3 has been shown to involve β2-integrins56 (Figure 2).

Once the monocyte has adhered it may start to transmigrate given the presence of appropriate signals. Several PMN-granule proteins were shown to exert chemotactic effects on monocytes in vitro. In this respect, the secondary granule–derived LL-37 and the primary granule–derived azurocidin, cathepsin G, and human neutrophil peptides 1-3 (HNP1-3) were demonstrated to be chemotactic for human and murine monocytes.10,57-62 Pertussis toxin sensitivity of these events points to the involvement of G-protein–coupled receptors. Further research elucidated that cathepsin G activates human formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1), whereas LL-37 acts via FPRL-159 (Figure 2). In addition, azurocidin was recently shown to induce monocyte extravasation via FPRs.10 However, the mechanisms and receptors underlying the monocyte extravasation triggered by HNPs still remain unknown. It is important to note that phenotypic differences of monocyte subsets may encompass distinct recruitment mechanisms, very likely reflected also in a specific recruitment of certain monocyte subsets by PMNs. In this context, it has recently been demonstrated that depletion of PMNs specifically reduces the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes in a murine recruitment assay.10 Interestingly, this deficiency in recruitment could almost completely be rescued by the local application of the supernatant from activated human PMNs. In subsequent experiments, LL-37 and azurocidin were identified as principal mediators of this effect, both of which activate Gr1+ monocytes via FPRs. The immediate availability of granule proteins, as well as the independence from de novo synthesis of target molecules, may allow for a rapid recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to the site of inflammation. At later time points, additional mechanisms, such as modulation of the chemokine network by PMNs or the effect of apoptotic PMNs, likely gain increasing importance for attracting monocytes to the inflamed tissue.

PMNs modify the chemokine network to induce monocyte recruitment

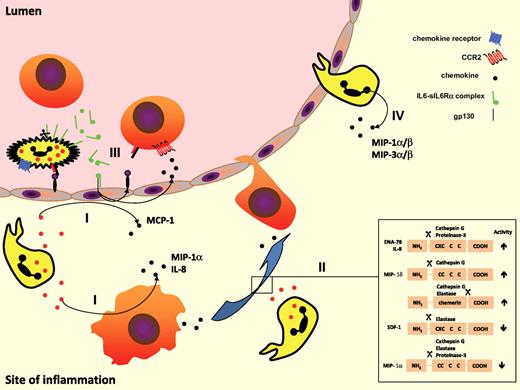

The transition from PMN to monocyte accumulation might also be secondary to a shift of the type of chemokine produced by stromal cells, inflammatory macrophages, or PMNs. Activation of endothelial cells may lead not only to enhanced CAM expression as described in Figure 2, but also to increase in the release of chemokines. In this context, PMN-derived proteinase-3 was shown to induce the secretion of MCP-1 (CCL2) from endothelial cells.50 As CCR2 is expressed on inflammatory monocytes only, this mechanism will induce adhesion and emigration of this particular monocyte subset (Figure 3). In contrast to these findings, PMN-derived azurocidin has been shown to induce chemokine release not from endothelial cells but from monocytes. This mechanism may be favored by azurocidin's localization not just in secretory vesicles, but also in primary granules.62,63 Azurocidin released from the latter compartment enhances the release of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and IL-8 from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–primed human monocytes64,65 (Figure 3). A more complex mechanism for the induction of IL-8 synthesis has been shown for LL-37 in epithelial cells. Here, epidermal growth factor receptor, which is present on airway epithelial cells, is transactivated by LL-37 via metalloproteinase-mediated cleavage of membrane-anchored epidermal growth factor receptor ligands. Downstream signaling involves the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal–related kinase pathway, leading to release of the potent chemoattractant IL-8.66 Similar results were obtained for monocytes, showing that LL-37 in these cells mediates the induction of IL-8 via a G-protein–coupled independent receptor, activating ERK and p38 pathways.67

PMN-mediated interference with the chemokine network promotes monocyte efflux. (I) PMN granule proteins promote de novo synthesis of monocyte-attracting chemokines such as MCP-1 and MIP-1α by neighboring endothelial cells and macrophages. (II) PMN-derived proteases cleave chemokine proforms either enhancing or attenuating their monocyte attracting capacities. (III) Complexes of soluble IL-6 and IL-6R shed from PMNs activate endothelial cells via gp130 to synthesize MCP-1 and VCAM-1. (IV) In the presence of appropriate stimuli (eg, fMLP, TNF, LPS), PMNs produce and secrete monocyte-attracting chemokines themselves.

PMN-mediated interference with the chemokine network promotes monocyte efflux. (I) PMN granule proteins promote de novo synthesis of monocyte-attracting chemokines such as MCP-1 and MIP-1α by neighboring endothelial cells and macrophages. (II) PMN-derived proteases cleave chemokine proforms either enhancing or attenuating their monocyte attracting capacities. (III) Complexes of soluble IL-6 and IL-6R shed from PMNs activate endothelial cells via gp130 to synthesize MCP-1 and VCAM-1. (IV) In the presence of appropriate stimuli (eg, fMLP, TNF, LPS), PMNs produce and secrete monocyte-attracting chemokines themselves.

Consistent with results for LL-37, HNP-1 induces IL-8 and MCP-1 production in human epithelial cells.68-70 In addition, epithelial cells produce IL-1β in response to HNP-1.71 Although there has been substantial research demonstrating chemokine and cytokine production in response to defensins, and HNP-1 in particular, the mechanism of induction is not well understood. In part, these effects might be mediated by activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB. In addition, it was recently demonstrated that IL-8 production in response to HNPs might be mediated through the purinergic P2 receptor P2Y6 receptor.72 In agreement, although treatment with adenosine triphosphate or uridine diphosphate, known ligands for P2Y6, selectively induced the release of IL-8, the HNP-1–induced production of IL-8 could be abrogated in the presence of P2Y6-antisense but not P2Y6-sense oligonucleotides.72

Although the family of PMN-derived serprocidins (serine proteases with antimicrobial activity) has not been shown to be involved in chemokine synthesis, their members may contribute to the chemokine network by proteolytic mechanisms (Figure 3). Indeed, many cytokines and chemokines and their respective receptors contain putative cleavage sites for neutrophil serine proteases. It is therefore not surprising that many receptors, cytokines, and other molecules have been found to be natural substrates for neutrophil serine proteases.73,74 It has been shown that the N-terminal processing of certain chemokines increases their affinity for their receptor. Thus, N-terminal cleavage of IL-8 by proteinase-375 and epithelial cell–derived neutrophil-activating protein-78 by cathepsin G76 releases truncated forms of these chemokines that have higher chemotactic activity than the full-length molecules. Similarly, N-terminal modification of MIP-1δ (CCL15) by cathepsin G increased its monocyte chemotactic activity many fold.77 Recently, it has been shown that activation of chemerin, which is known to attract antigen-presenting cells, can be mediated by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G through the proteolytic removal of a C-terminal peptide.78 However, N-terminal truncation of a chemokine through proteolysis does not always lead to increased cellular activation. Processing of stromal cell–derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) by neutrophil elastase79 and proteolysis of MIP-1α isoforms by all 3 neutrophil serine proteases80 were shown to result in loss of chemotactic activity. Therefore, the net effect of the proteolytic modification of chemokines by neutrophil serine proteases in vivo remains unclear.

It has been shown that PMNs that have migrated to the site of inflammation can up-regulate their production of chemokines81-83 (Figure 3), supporting the notion that, in this way, PMNs participate in the regulation of leukocyte accumulation. In terms of production, the principal chemokine produced by PMNs is IL-8, which activates PMNs in an autocrine loop. IL-8 binds to CXCR2 expressed not just on PMNs, but also on monocytes. Therefore, it is not surprising that IL-8 also mediates adhesion of human monocytes to the endothelium.84 Similarly, growth-related gene product alpha also binds CXCR2 and thus induces adhesion of human monocytes.85 The relative expression of CXCR2 on monocyte subsets is currently under intensive investigation and it will be interesting to see in what way differences in the expression pattern affect the recruitment behavior of monocyte subsets. Appropriately stimulated PMNs are also able to produce CC chemokines such as MIP-1α and MIP-1β.86 Both chemokines bind primarily to CCR1, thus acting on inflammatory monocytes. It has also been described that PMNs are able to express MIP-3α (CCL20) and MIP-3β (CCL19) when exposed to proinflammatory stimuli, such as TNF.87 A recent study by Le Borgne et al indicates that inflammatory monocytes are recruited to the inflamed dermis via CCR6 and its ligand CCL20.37

In addition, it has been shown that IL-6 has a rather unexpected role in leukocyte recruitment in vivo, as a result of the fact that the IL-6–sIL-6Rα complex can activate human and murine endothelial cells to secrete IL-8 and MCP-1, as well as the expression of adhesion molecules88 (Figure 3). Noticeably, IL-6 activation of endothelial cells occurs in vivo, although these cells, like other stromal cells, express the gp130-transducing protein of the IL-6 receptor complex but not the 80-kDa ligand-binding subunit, IL-6Rα, and in vitro, this activation could be achieved only when IL-6 was combined with soluble recombinant IL-6Rα. IL-6Rα expression is limited in humans to leukocyte and hepatocyte membranes89 but can be shed from the PMN membrane into a soluble form, which is found at high concentrations in PMN-enriched inflammatory fluids.90 The sIL-6Rα combines with IL-6 to bind gp130 on the membranes of stromal cells, and activates these cells in a mechanism called trans-signaling.91 Although the observation that IL-6–induced IL-8 secretion was established using supraphysiological sIL-6Rα concentrations, other investigators have reported that the IL-6–sIL-6Rα complex primarily induced MCP-1 and not IL-8 secretion by human mesangial cells, fibroblasts, or blood mononuclear cells.92,93 Several years ago, 2 groups used several recruitment assays in humans and mice that allowed them to observe that the IL-6–sIL-6Rα complex favors the transition from PMN to monocyte in inflammation.94,95 Addition of sIL-6Rα, at concentrations comparable with those measured in inflammatory synovial fluids, to thrombin-activated endothelial cells induced MCP-1 secretion. Moreover, it has been shown that chemoattractant stimulation of PMNs, but not monocytes, results in IL-6Rα shedding involving TNF-α converting enzyme.96 Interestingly, this could explain why in inflammatory animal models, the neutrophilic infiltrate is more dominant in IL-6 knockout mice than in wild-type animals.97 Similar observations and conclusions have been made by Hurst et al using mesothelial cells and validated in IL-6 knockout mice.94 In wild-type animals, the local infiltrate of acute peritonitis was made primarily of PMNs followed by monocytes; however, in the IL-6 knockout animals, PMNs were the only cells present in the infiltrate. The injection of exogenous IL-6–sIL-6Rα complex restored the monocytic influx. Chalaris et al could recently evidence that apoptotic PMNs shed IL-6R in a caspase-dependent manner, therefore linking signals from PMNs undergoing apoptosis with subsequent monocyte infiltration.14

Signals from apoptotic PMNs

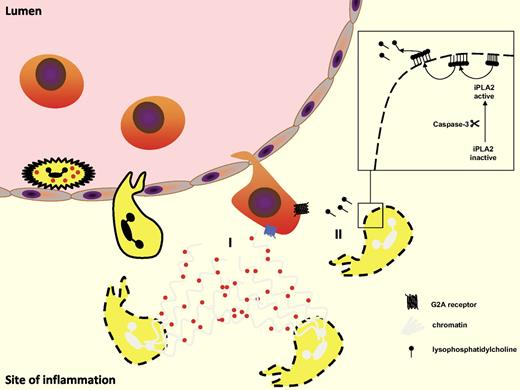

PMNs are short-lived cells. Their apoptosis is a tightly regulated process involving death factors such as FasL, TNF, caspase, Bcl-2 family, reactive oxygen species, and pathogens.98 Once PMNs migrate toward the site of inflammation, their life span increases because of the presence of survival signals. PMN survival factors include proinflammatory mediators such as nuclear factor κB, LPS, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, Foxo3a,99 hypoxia,100 and survivin.101 In response to proinflammatory signals, PMNs not only extend their life span but also release a web of DNA in which granule proteins are enweaved.102 The final stage of such a mechanism is the apoptotic PMN with its inside turned out. Exposure of granule proteins and entrapment within a net of DNA may contribute to creating a gradient of chemotactic granule components relevant to monocyte recruitment (Figure 4). The mechanisms underlying such recruitment mechanism are, however, to be expected as those stated in Figure 2.

Apoptotic PMN attract monocytes. (I) Apoptotic PMNs release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) with trapped granule proteins that may attract inflammatory monocytes. (II) Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is released from apoptotic cells in a caspase-3–dependent manner. LPC then activates monocytic G2A receptor–inducing monocyte recruitment.

Apoptotic PMN attract monocytes. (I) Apoptotic PMNs release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) with trapped granule proteins that may attract inflammatory monocytes. (II) Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is released from apoptotic cells in a caspase-3–dependent manner. LPC then activates monocytic G2A receptor–inducing monocyte recruitment.

Apart from release of granule proteins, apoptotic PMNs may set free attraction signals leading to influx of monocytes. In recent years, several apoptotic cell–derived “find me” signals were identified. Among them are S19 ribosomal protein dimmer, split tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, thrombospondin-1, and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), of which the latter has received much attention (Figure 4). Applying an in vitro transmigration assay, Lauber et al demonstrated that apoptotic cells in fact secrete LPC that induces attraction in a caspase-3–dependent fashion.103 In this context, it should also be noted that studies by Kim et al could identify LPC as an eat-me signal on the apoptotic cell surface, which is recognized by naturally occurring IgM antibodies.104 On the basis of these findings, the nature of the poorly characterized eat-me signals might be reassessed. In the field of atherosclerosis research it has been well established that LPC is a major lipid component of oxidized low-density lipoprotein particles. Thus, one could speculate whether the oxidized low-density lipoprotein–like sites on the surface of the apoptotic cell are identical to sites exposing LPC. This seems even more relevant, considering the recently established importance of PMNs in atherosclerosis,11,105,106 which may herald the influx of inflammatory monocytes to the inflamed vessel wall. The model of monocyte attraction in response to LPC from apoptotic cells suggests that a calcium-independent phospholipase A2 is activated in a caspase-3–dependent manner. Activated independent phospholipase A2 subsequently starts hydrolyzing phosphatidylcholine, yielding arachidonic acid LPC. LPC in turn is externalized and secreted by an as-yet-unknown mechanism.107 Two putative receptors for LPC have been identified on monocytes, G2A and GRP4. However, whether they are differentially expressed on monocyte subsets has yet to be investigated. Peter et al have recently demonstrated that the chemotactic activity of LPC is mediated via activation of the G-protein–coupled receptor G2A, but not its relative GPR4.108

More recently, it has been shown that changes in membrane composition of apoptotic cells (negative surface charges) initiate attractive signals for phagocytes including monocytes and macrophages.109 Although such mechanism has been established for epithelial cells, it is feasible to anticipate that apoptotic PMNs may also generate such electric signals resulting in electrotaxis of monocytes.

Integrated view of the PMN-monocyte axis

Circulating murine monocytes consist of at least 2 subsets, which are referred to as Gr1+ inflammatory monocytes and Gr1− resident monocytes.28 The latter have initially been proposed to be involved in the renewal of resident macrophages and dendritic cells. Although little evidence in favor of this hypothesis accumulated over the years, Auffray et al have recently show that this subset of monocytes may patrol vessels in the microcirculation using LFA-1 and CX3CR1.40 In response to tissue damage (sterile and nonsterile), Gr1− monocytes were suggested to rapidly invade surrounding tissue. The authors of the study conclude that because of the early extravasation of these cells as well as the gene profile exhibited by these cells, Gr1− monocytes may be of central importance in regulating early effector functions, thus being important in recruiting PMNs, Gr1+ monocytes, and T cells.110 However, PMNs are equally rapidly recruited and in conjunction with tissue-resident macrophages and mast cells may outnumber the effects initiated by Gr1− monocytes. At later stages, Gr1− monocytes were suggested to acquire an anti-inflammatory phenotype, termed M2 or alternative activation pattern.110 M2-activated macrophages are characterized by their involvement in tissue remodeling, wound repair, and immunomodulation. As of now, PMNs have not been found to be involved in extravasation of Gr1− monocytes or the M2 polarization of macrophages.

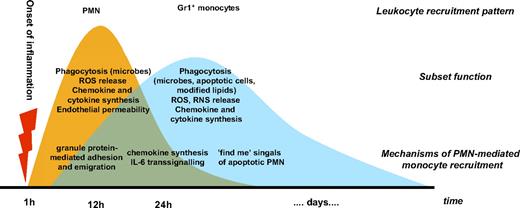

This contrasts to the involvement of PMNs in the recruitment and activation of Gr1+ monocytes (Figure 5). These infiltrate inflamed tissues several hours after onset of the injury.10 PMN-mediated mechanisms may herald and sustain the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Deposition of PMN granule proteins on the endothelium as well as chemotactic activity exerted via FPRs are immediately initiated upon PMN extravasation. As these mechanisms do not require de novo synthesis, they may contribute to the ignition of the recruitment of Gr1+ monocytes. At later stages, PMN-mediated alterations of the chemokine milieu may outweigh the importance of granule proteins. Mechanisms by which PMNs modulate the local chemokine network outlined in Figure 3 result in the production of ligands for CCR1 (eg, MIP-1α, MIP-1δ), CCR2 (eg, MCP-1), CCR6 (eg, MIP-3α), and CXCR2 (eg, IL-8, epithelial cell–derived neutrophil-activating protein-78), all of which were shown to be preferentially expressed by inflammatory monocytes. Finally, apoptotic PMNs produce LPC, which attracts monocytes via G2A receptor. However, at this stage it is not known whether this mechanism is specific for the recruitment of a certain monocyte subset. Due to the importance of inflammatory monocytes in clearance of apoptotic debris, it is, however, predictable that LPC may preferably attract inflammatory monocytes.

Integrated view of the PMN-monocyte axis in inflammation. PMNs are rapidly recruited to the site of inflammation. Granule proteins allow for almost instant recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Mechanisms requiring de novo synthesis of adhesion molecules and chemokines come into effect at later time points. Finally, signals generated by apoptotic PMNs attract inflammatory monocytes. Thus, the axis of PMNs and Gr1+ monocytes provides an acceleration of proinflammatory events.

Integrated view of the PMN-monocyte axis in inflammation. PMNs are rapidly recruited to the site of inflammation. Granule proteins allow for almost instant recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Mechanisms requiring de novo synthesis of adhesion molecules and chemokines come into effect at later time points. Finally, signals generated by apoptotic PMNs attract inflammatory monocytes. Thus, the axis of PMNs and Gr1+ monocytes provides an acceleration of proinflammatory events.

Gr1+ monocytes exert far-reaching proinflammatory activities such as bacterial phagocytosis, tissue degradation, and secretion of inflammation-sustaining cytokines and reactive oxygen species.110 Such proinflammatory activities are certainly beneficial in acute bacterial infections. In chronic inflammatory disorders, such as atherosclerosis or rheumatoid arthritis, these mechanisms are, however, harmful. Interestingly, PMNs not only contribute to the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes but also support monocyte-driven proinflammatory events by activation of monocytes and macrophages. In this respect, it has recently been shown that PMN secretion products promote an M1 inflammatory polarization of macrophages characterized by up-regulation of costimulatory molecules; release of TNF, IFNγ, and IL-6; as well as increased phagocytic capacity.111,112 In addition, PMN granule proteins enhance the production of reactive oxygen species.113,114 Thus, various experimental setups provide evidence that the axis of PMNs and inflammatory monocytes promotes accelerated and sustained inflammation.

PMN-mediated monocyte recruitment as therapeutic option

Specific interference with PMNs for therapeutic purposes has so far been difficult, as blocking of PMN function may entail a compromised host defense system. Typical examples are attempts of blocking PMN adhesion by inhibition of cell adhesion molecules and selectins.115 The redundancy of mediators released by PMNs is yet another challenge to be dealt with. For example, inhibition of neutrophil elastase might be relatively ineffective if not at the same time inhibiting also cathepsin G, proteinase-3, and matrix metalloproteinases as was shown in a rat model of airway inflammation.116 Hence, interfering with PMN-mediated recruitment of inflammatory monocytes may allow for more selective targeting of inflammatory processes.

To interfere with PMN granule proteins one may target PMN degranulation.117 This, however, would also affect externalization of adhesion receptors blocking PMN extravasation. Interference with individual granule proteins may hence provide a more elegant and specific approach. However, current research regarding PMN-derived antimicrobial peptides rather focuses on using analogues to be applied in infectious diseases.118 To date, there are no studies aimed at specifically antagonizing LL-37, azurocidin, or HNPs. This is surprising as endothelial deposition of platelet chemokines leading to enhanced monocyte adhesion and extravasation has recently become an interesting target in inflammation research.119 Such work may serve as proof of principle and stimulate further research targeting PMN granule deposition. An alternate approach is the direct interference with chemokines. CCR2 is the classical chemokine to induce recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. As described in Figure 2, ligands for CCR2, such as MCP-1, are produced either by the PMN itself, or by cells activated by PMN secretion products. CCR2 is known to be involved in many inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis, both of which contribute PMNs in early stages. Small molecule antagonists to CCR2 were shown to be effective in rheumatoid arthritis,120 possibly because they antagonize PMN-derived CCR2 ligands. While rheumatoid arthritis has been targeted, yet another approach based on IL-6 trans-signaling has evolved. The sgp130Fc fusion protein is a specific inhibitor of the IL-6 trans-signaling mediated by the IL-6/sIL-6R complex. In a murine model of antigen-induced arthritis, it was shown that sgp130Fc abrogates not only the development of arthritis but also the influx of monocytes.121

Taken together, the multifaceted action of PMNs in recruiting and activating monocytes may offer a powerful target to interfere with sustained inflammatory responses of monocyte-driven inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR809, SO876/3-1, WE1913/7-2, WE1913/10-1), the German Heart Foundation/German Foundation of Heart Research, the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research “BIOMAT” within the Faculty of Medicine at the RWTH Aachen University (VV-B113), and the Swedish Research Council.

Authorship

Contribution: O.S., L.L., and C.W. designed and wrote the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Oliver Soehnlein, Institute for Molecular Cardiovascular Research, Pauwelsstr. 30, RWTH University Aachen, 52074 Aachen, Germany; e-mail: osoehnlein@ukaachen.de.