Abstract

Malaria parasites are known to invade and develop in erythrocytes and reticulocytes, but little is known about their infection of nucleated erythroid precursors. We used an in vitro cell system that progressed through basophilic, polychromatic, orthochromatic, and reticulocyte stages to mature erythrocytes. We show that orthochromatic cells are the earliest stages that may be invaded by Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of fatal human malaria. Susceptibility to invasion is distinct from intracellular survival and occurs at a time of extensive erythroid remodeling. Together these data suggest that the potential for complexity of host interactions involved in infection may be vastly greater than hitherto realized.

Introduction

Approximately 40% of the world's population is at risk of developing malaria,1 which is caused by infections of the human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. During blood-stage infection, which causes all symptoms and pathologies of malaria, the parasite infects mature erythrocytes and reticulocytes. Isolated reports suggest that nucleated erythroid progenitors may also be infected,2,3 but little is known of when in maturation they become susceptible and the complexity of associated cellular remodeling events. There is considerable interest in these parameters, because they underlie host interactions with a major human pathogen that is thought to have profoundly influenced erythroid development.4

We have used an in vitro model system using primary cells to study commitment to the erythroid lineage and differentiation of committed progenitors to reticulocytes.5,6 The advantages are that the kinetics of differentiation in vitro closely resembles that of erythroid cell maturation in the bone marrow, and differentiation occurs in a relatively synchronous manner. In this system we examine malarial infection during complex, cellular remodeling at terminal steps of erythroid differentiation. We show that despite prior reports,3 only orthochromatic erythroblasts can be infected by falciparum malaria and that the process of infection is functionally segregated into 2 categories: early-mid orthochromatic erythroblasts can support parasite invasion, but only late orthochromatic/nascent reticulocytes sustain intracellular parasite growth.

Methods

Primary human erythroid cultures and flow cytometry

Human primary erythroblasts were generated by culturing CD34+ early hematopoietic progenitors initially isolated from growth factor–mobilized peripheral blood (purchased from ALL Cells Inc). Culture and subsequent flow cytometry sorting of cultured cells were carried out as previously described.5 On day 7 of culture, erythroid cells positive for the transferrin receptor (CD71) were purified to 98% to 99% using a MoFlo high-speed flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Sorted cells were subsequently cultured (in day 8 media formulation) and fed once more on day 10 with media containing only erythropoietin (2 units/mL).

Parasite infection

P falciparum 3D7 was synchronized by successive rounds of Percoll and sorbitol. Late-stage schizonts were used to initiate infection of 2 × 106 erythroblasts at a multiplicity of infection = 5. Erythroblasts were infected on day 5 (proerythroblasts/basophilic), day 10 (polychromatic stage), or days 14 and 16 (orthochromatic) of culture. Cells were resuspended at 1 × 106/mL in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 30% human serum and 2 units/mL erythropoietin and incubated in 5% CO2-humidified chamber at 37°C. Infected cells were collected at indicated time points and stained with Giemsa to monitor parasitemia or benzidine and hematoxylin to monitor the differentiation program of erythroblasts.7 A counter who was blinded to sample identity enumerated numbers of infected cells.

Transcriptional analysis

Primary human cells from 3 different donors were cultured and harvested at the polychromatic (day 10) and early-mid orthochromatic (day 14) stage of development. RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) and purified with RNeasy columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturers' recommendations. One microgram RNA was used for in vitro transcription reactions, and cRNA was hybridized onto Affymetrix HG-U133 plus 2.0 chips according to Affymetrix protocols. Normalization and statistical analysis was performed using Dchip (Harvard School of Public Health)8 model-based expression. To calculate the false discovery rate (q-value), we input P values into the R add-in package QVALUE (Princeton University)9 and estimated it to be approximately 0.7%.

Results and discussion

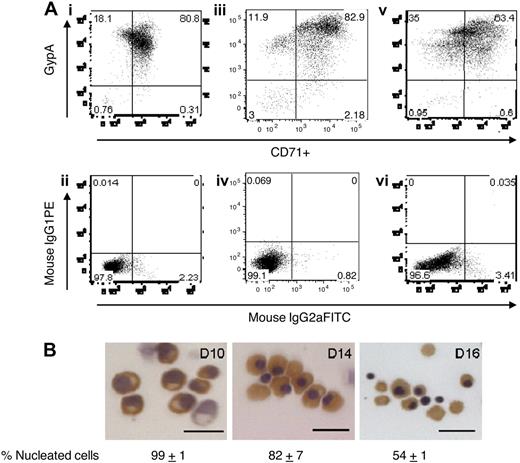

We purified CD34+ early hematopoietic progenitors from several healthy donors to generate primary human erythroid progenitors and erythroblasts. During the first 7 days of culture, CD34+ cells commit to the erythroid lineage, and begin to express on their surface erythropoietin and transferrin receptors (CD71) and subsequently glycophorin A as they differentiate. We purified CD71+ erythroblasts on day 7 to obtain an erythroid cell population that was greater than 98% pure as judged by flow cytometry analysis on day 10 (Figure 1A). This purity was sustained at days 14 and 16 with a gradual decrease in expression of CD71 and maintained levels of glycophorin A. Benzidine staining shows that polychromatic erythroblasts (day 10) had begun synthesizing hemoglobin (Figure 1B). At day 14, approximately 80% of erythroblasts were nucleated orthochromatic and by day 16 half of the erythroblasts were enucleating (Figure 1B).

Differentiation of primary human erythroblasts in culture. CD34+-derived erythroid progenitors were differentiated into erythroblasts and reticulocytes after flow cytometry sorting for transferrin receptor (CD71)–positive cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis for glycophorin A (gypA) and CD71 on days 10, 14, and 16 of culture. Day 10 (i), day 14 (iii), and day 16 (v) cells were at least 95% positive for erythroid cells. Panels ii, iv, and vi are isotype controls to show antibody specificity. (B) Hematoxylin/benzidine staining of day 10 polychromatic erythroblasts, day 14 early orthochromatic erythroblasts, and day 16 enucleating/reticulocytes. All populations contained hemoglobin (brown staining). Bar represents 20 μm.

Differentiation of primary human erythroblasts in culture. CD34+-derived erythroid progenitors were differentiated into erythroblasts and reticulocytes after flow cytometry sorting for transferrin receptor (CD71)–positive cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis for glycophorin A (gypA) and CD71 on days 10, 14, and 16 of culture. Day 10 (i), day 14 (iii), and day 16 (v) cells were at least 95% positive for erythroid cells. Panels ii, iv, and vi are isotype controls to show antibody specificity. (B) Hematoxylin/benzidine staining of day 10 polychromatic erythroblasts, day 14 early orthochromatic erythroblasts, and day 16 enucleating/reticulocytes. All populations contained hemoglobin (brown staining). Bar represents 20 μm.

We next tested the ability of P falciparum to infect erythroblasts matured across representative stages of differentiation (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 2Ai, day 5 pro-/basophilic erythroblast cells were refractory to infection. At day 10, polychromatic cells appeared to be inefficiently infected. In contrast, at day 16 late orthochromatic erythroblasts supported entry (detected by presence of ring-stage parasites) as well as intracellular parasite maturation (detected by presence of trophozoite- and schizont-stage parasites). To further refine the time of onset of infection, we compared infection in polychromatic (day 10) and mid (day 14) and late (day 16) orthochromatic stages. We again found that day 10 polychromatic cells were poorly invaded (with low levels of ring-stage parasites found in a small fraction of cells containing condensed nuclei; Figure 2Bi-ii). Ring-stage parasites were abundant in day 14 midorthochromatic stages but did not undergo intracellular maturation to the trophozoite and schizont stages (Figure 2Biii-iv). In contrast, in late-stage orthochromatic cells (day 16), 80% of intracellular parasite forms matured through the second 24 hours to form schizont-stage parasites (Figure 2Aii,Bv-vi), essentially analogous to infection seen in mature red cells (not shown). These data suggest that parasite entry and maturation can be segregated as erythroid progenitors differentiate.

Characterization of human erythroblast maturation by susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection and by transcriptional response. (Ai) Percentage of day 5, 10, and 16 erythroblasts infected by Plasmodium falciparum. No infection is detected in pro-/basophilic erythroblasts (day 5). At day 10, when the population is largely at the polychromatic stage a few early orthochromatic cells are detected that can also be infected. (ii) Infection is seen in early/mid (day 14, ■) and late (day 16, ■) orthochromatic erythroblasts (N indicates nucleated; and E, enucleated), whereas only minor infection can be detected in polychromatic erythroblasts (day 10).  represent the percentage of nucleated/enucleated cells in the population, and ■ represent the proportion infected (marked with numbers) in each subset. Under these conditions, in cultures containing only mature erythrocytes we detect 60% infection. Error bars indicate SEM; n = 3 for day 10; n = 3 for day 14; n = 2 for day 16. (B) Brightfield images of Giemsa-stained infected erythroblast cells at 22 hours after invasion (hpi indicates hours of intracellular parasite growth; day 10, i; day 14, iii; day 16, v) and at 40 hpi (day 10, ii; day 14, iv; day 16, vi). On day 10 at 22 hpi, a few cells contain ring-stage parasites (i,

represent the percentage of nucleated/enucleated cells in the population, and ■ represent the proportion infected (marked with numbers) in each subset. Under these conditions, in cultures containing only mature erythrocytes we detect 60% infection. Error bars indicate SEM; n = 3 for day 10; n = 3 for day 14; n = 2 for day 16. (B) Brightfield images of Giemsa-stained infected erythroblast cells at 22 hours after invasion (hpi indicates hours of intracellular parasite growth; day 10, i; day 14, iii; day 16, v) and at 40 hpi (day 10, ii; day 14, iv; day 16, vi). On day 10 at 22 hpi, a few cells contain ring-stage parasites (i,  ). Judging from staining of condensed nuclei, these cells are at the early orthochromatic stage. At 40 hpi, no mature schizonts are seen, but ring vacuoles (ii,

). Judging from staining of condensed nuclei, these cells are at the early orthochromatic stage. At 40 hpi, no mature schizonts are seen, but ring vacuoles (ii,  ) may remain. On day 14, at 22 hpi, more than half the cells show rings (iii,

) may remain. On day 14, at 22 hpi, more than half the cells show rings (iii,  ), which fail to mature to schizonts, but ring vacuoles (iv,

), which fail to mature to schizonts, but ring vacuoles (iv,  ) are prominently detected. Half of these cells become vacuolated by 40 hpi (iv, [

) are prominently detected. Half of these cells become vacuolated by 40 hpi (iv, [ ]). On day 16, at 22 hpi and 40 hpi, respectively, ring-stage parasites (v,

]). On day 16, at 22 hpi and 40 hpi, respectively, ring-stage parasites (v,  ) and schizont-stage parasites with hemozoin crystals (vi,

) and schizont-stage parasites with hemozoin crystals (vi,  ) are evident in nucleated, late orthochromatic erythroblasts. Photomicrographs were taken by light microscopy with a Zeiss Axioskop upright microscope and Nuance spectral camera/unmixing system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation) using a 100× objective. Scale represents 5 μm. (C) Transcriptional profile of day 14 versus day 10 erythroblasts. Up-regulated transcripts are denoted with red squares; down-regulated, with blue diamonds; unchanged, with gray crosses. As expected, hemoglobins a and b were highly transcribed (spot 1, purple asterisks), erythrocyte protein band 4.1 (epb41) was up-regulated, and adducin 2 (add2) was down-regulated (inset, black squares, spots 12 and 13, respectively), suggesting assembly of the cytoskeleton was still in progress. Beta-actin (actb, spot 2), glycophorins (gypc spot 3, gypa spot 4, gypb spot 6), spectrin (spta1 spot 5, sptb spot 9), ankyrin (ank1 spot 7), band 3 (slc4a1 spot 8), Duffy (darc spot 10), and adducin 3 (add3 spot 11) are all expressed but show no significant change (fold change < 2, black squares). In addition erythropoietin receptor (epor spot 14, inset) transcript is reduced relative to transferrin receptor (cd71 spot 15, green circles) but nonetheless detectable. Bcl2-like 1 (bcl2l1 or bcl-xL; spot 18), a marker for terminal stages of erythropoiesis,10 is up-regulated 2.6-fold (P = .006, q = 0.005). In addition, it appears early orthochromatic cells are exiting the cell cycle because both cyclins D3 and E2 (ccnd3, ccne2; spots 16 and 17, respectively) are down-regulated ∼ 3-fold compared with polychromatic cells (P = .002, q = 0.003 and P = .02, q > 0.007, respectively). (D) Diagram displaying differential susceptibility of erythroblasts to P falciparum infection. Whereas orthochromatic cells can support parasite entry, only enucleating erythroblasts/nascent reticulocytes support intracellular parasite growth.

) are evident in nucleated, late orthochromatic erythroblasts. Photomicrographs were taken by light microscopy with a Zeiss Axioskop upright microscope and Nuance spectral camera/unmixing system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation) using a 100× objective. Scale represents 5 μm. (C) Transcriptional profile of day 14 versus day 10 erythroblasts. Up-regulated transcripts are denoted with red squares; down-regulated, with blue diamonds; unchanged, with gray crosses. As expected, hemoglobins a and b were highly transcribed (spot 1, purple asterisks), erythrocyte protein band 4.1 (epb41) was up-regulated, and adducin 2 (add2) was down-regulated (inset, black squares, spots 12 and 13, respectively), suggesting assembly of the cytoskeleton was still in progress. Beta-actin (actb, spot 2), glycophorins (gypc spot 3, gypa spot 4, gypb spot 6), spectrin (spta1 spot 5, sptb spot 9), ankyrin (ank1 spot 7), band 3 (slc4a1 spot 8), Duffy (darc spot 10), and adducin 3 (add3 spot 11) are all expressed but show no significant change (fold change < 2, black squares). In addition erythropoietin receptor (epor spot 14, inset) transcript is reduced relative to transferrin receptor (cd71 spot 15, green circles) but nonetheless detectable. Bcl2-like 1 (bcl2l1 or bcl-xL; spot 18), a marker for terminal stages of erythropoiesis,10 is up-regulated 2.6-fold (P = .006, q = 0.005). In addition, it appears early orthochromatic cells are exiting the cell cycle because both cyclins D3 and E2 (ccnd3, ccne2; spots 16 and 17, respectively) are down-regulated ∼ 3-fold compared with polychromatic cells (P = .002, q = 0.003 and P = .02, q > 0.007, respectively). (D) Diagram displaying differential susceptibility of erythroblasts to P falciparum infection. Whereas orthochromatic cells can support parasite entry, only enucleating erythroblasts/nascent reticulocytes support intracellular parasite growth.

Characterization of human erythroblast maturation by susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection and by transcriptional response. (Ai) Percentage of day 5, 10, and 16 erythroblasts infected by Plasmodium falciparum. No infection is detected in pro-/basophilic erythroblasts (day 5). At day 10, when the population is largely at the polychromatic stage a few early orthochromatic cells are detected that can also be infected. (ii) Infection is seen in early/mid (day 14, ■) and late (day 16, ■) orthochromatic erythroblasts (N indicates nucleated; and E, enucleated), whereas only minor infection can be detected in polychromatic erythroblasts (day 10).  represent the percentage of nucleated/enucleated cells in the population, and ■ represent the proportion infected (marked with numbers) in each subset. Under these conditions, in cultures containing only mature erythrocytes we detect 60% infection. Error bars indicate SEM; n = 3 for day 10; n = 3 for day 14; n = 2 for day 16. (B) Brightfield images of Giemsa-stained infected erythroblast cells at 22 hours after invasion (hpi indicates hours of intracellular parasite growth; day 10, i; day 14, iii; day 16, v) and at 40 hpi (day 10, ii; day 14, iv; day 16, vi). On day 10 at 22 hpi, a few cells contain ring-stage parasites (i,

represent the percentage of nucleated/enucleated cells in the population, and ■ represent the proportion infected (marked with numbers) in each subset. Under these conditions, in cultures containing only mature erythrocytes we detect 60% infection. Error bars indicate SEM; n = 3 for day 10; n = 3 for day 14; n = 2 for day 16. (B) Brightfield images of Giemsa-stained infected erythroblast cells at 22 hours after invasion (hpi indicates hours of intracellular parasite growth; day 10, i; day 14, iii; day 16, v) and at 40 hpi (day 10, ii; day 14, iv; day 16, vi). On day 10 at 22 hpi, a few cells contain ring-stage parasites (i,  ). Judging from staining of condensed nuclei, these cells are at the early orthochromatic stage. At 40 hpi, no mature schizonts are seen, but ring vacuoles (ii,

). Judging from staining of condensed nuclei, these cells are at the early orthochromatic stage. At 40 hpi, no mature schizonts are seen, but ring vacuoles (ii,  ) may remain. On day 14, at 22 hpi, more than half the cells show rings (iii,

) may remain. On day 14, at 22 hpi, more than half the cells show rings (iii,  ), which fail to mature to schizonts, but ring vacuoles (iv,

), which fail to mature to schizonts, but ring vacuoles (iv,  ) are prominently detected. Half of these cells become vacuolated by 40 hpi (iv, [

) are prominently detected. Half of these cells become vacuolated by 40 hpi (iv, [ ]). On day 16, at 22 hpi and 40 hpi, respectively, ring-stage parasites (v,

]). On day 16, at 22 hpi and 40 hpi, respectively, ring-stage parasites (v,  ) and schizont-stage parasites with hemozoin crystals (vi,

) and schizont-stage parasites with hemozoin crystals (vi,  ) are evident in nucleated, late orthochromatic erythroblasts. Photomicrographs were taken by light microscopy with a Zeiss Axioskop upright microscope and Nuance spectral camera/unmixing system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation) using a 100× objective. Scale represents 5 μm. (C) Transcriptional profile of day 14 versus day 10 erythroblasts. Up-regulated transcripts are denoted with red squares; down-regulated, with blue diamonds; unchanged, with gray crosses. As expected, hemoglobins a and b were highly transcribed (spot 1, purple asterisks), erythrocyte protein band 4.1 (epb41) was up-regulated, and adducin 2 (add2) was down-regulated (inset, black squares, spots 12 and 13, respectively), suggesting assembly of the cytoskeleton was still in progress. Beta-actin (actb, spot 2), glycophorins (gypc spot 3, gypa spot 4, gypb spot 6), spectrin (spta1 spot 5, sptb spot 9), ankyrin (ank1 spot 7), band 3 (slc4a1 spot 8), Duffy (darc spot 10), and adducin 3 (add3 spot 11) are all expressed but show no significant change (fold change < 2, black squares). In addition erythropoietin receptor (epor spot 14, inset) transcript is reduced relative to transferrin receptor (cd71 spot 15, green circles) but nonetheless detectable. Bcl2-like 1 (bcl2l1 or bcl-xL; spot 18), a marker for terminal stages of erythropoiesis,10 is up-regulated 2.6-fold (P = .006, q = 0.005). In addition, it appears early orthochromatic cells are exiting the cell cycle because both cyclins D3 and E2 (ccnd3, ccne2; spots 16 and 17, respectively) are down-regulated ∼ 3-fold compared with polychromatic cells (P = .002, q = 0.003 and P = .02, q > 0.007, respectively). (D) Diagram displaying differential susceptibility of erythroblasts to P falciparum infection. Whereas orthochromatic cells can support parasite entry, only enucleating erythroblasts/nascent reticulocytes support intracellular parasite growth.

) are evident in nucleated, late orthochromatic erythroblasts. Photomicrographs were taken by light microscopy with a Zeiss Axioskop upright microscope and Nuance spectral camera/unmixing system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation) using a 100× objective. Scale represents 5 μm. (C) Transcriptional profile of day 14 versus day 10 erythroblasts. Up-regulated transcripts are denoted with red squares; down-regulated, with blue diamonds; unchanged, with gray crosses. As expected, hemoglobins a and b were highly transcribed (spot 1, purple asterisks), erythrocyte protein band 4.1 (epb41) was up-regulated, and adducin 2 (add2) was down-regulated (inset, black squares, spots 12 and 13, respectively), suggesting assembly of the cytoskeleton was still in progress. Beta-actin (actb, spot 2), glycophorins (gypc spot 3, gypa spot 4, gypb spot 6), spectrin (spta1 spot 5, sptb spot 9), ankyrin (ank1 spot 7), band 3 (slc4a1 spot 8), Duffy (darc spot 10), and adducin 3 (add3 spot 11) are all expressed but show no significant change (fold change < 2, black squares). In addition erythropoietin receptor (epor spot 14, inset) transcript is reduced relative to transferrin receptor (cd71 spot 15, green circles) but nonetheless detectable. Bcl2-like 1 (bcl2l1 or bcl-xL; spot 18), a marker for terminal stages of erythropoiesis,10 is up-regulated 2.6-fold (P = .006, q = 0.005). In addition, it appears early orthochromatic cells are exiting the cell cycle because both cyclins D3 and E2 (ccnd3, ccne2; spots 16 and 17, respectively) are down-regulated ∼ 3-fold compared with polychromatic cells (P = .002, q = 0.003 and P = .02, q > 0.007, respectively). (D) Diagram displaying differential susceptibility of erythroblasts to P falciparum infection. Whereas orthochromatic cells can support parasite entry, only enucleating erythroblasts/nascent reticulocytes support intracellular parasite growth.

To better understand changes in host cells as they become susceptible to invasion, we analyzed the transcriptional changes associated with maturation from polychromatic to early-mid orthochromatic erythroblasts (days 10 and 14, respectively). Although most markers of mature erythrocytes did not change (as described in detail in the legend of Figure 2C), overall as many as 2038 transcripts (∼ 15%) display significant change with 1065 down-regulated and 973 up-regulated (fold change > 2, P < .01, q-value < 0.007; Figure 2C). The agreement in changes of expression profiles between donors (in pairwise comparisons) was 90% (not shown), suggesting that the in vitro maturation process was highly reproducible. Together these data suggest that maturation of polychromatic to orthochromatic stages is associated with complex cellular remodeling. Thus, a priori it is difficult to immediately identify a limited set of high-value candidates linked to susceptibility to P falciparum invasion. Rather susceptibility to invasion may well be linked to more complex changes characteristic of orthochromatic maturation.

Both P falciparum and P vivax infect erythroid progenitors,2,3,11 suggesting parasitization of these cells occurs independently of species. Our data show that polychromatic cells are not infected by P falciparum, even though these cells express a major invasion receptor glycophorin A and are highly endocytic (as judged by transferrin receptor levels). This is consistent with the idea that changes in receptor species, posttranslational modifications, signaling, and/or cytoskeletal processes may underlie susceptibility to infection gained at the orthochromatic stage. Finally, a large proportion (∼ 50%) of infected, early-mid orthochromatic cells were vacuolated compared with uninfected counterparts, suggesting induction of abnormalities that may be relevant to dyserythropoiesis. Because there is extensive remodeling between polychromatic and orthochromatic cells, susceptibility to invasion may be a complex trait involving multiple parameters, and this in vitro culture system should enable systematic analyses of those parameters.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mohandas Narla for helpful discussion during the course of this study.

The work was supported in part by grants to K.H. (National Institutes of Health [NIH]: R01 AI 039071, R01 HL 079397, and P01 HL 078826; UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases [TDR]), to A.W. (NIH: RO1CA98550, Giving Tree Foundation), to P.A.T. (Institutional National Research Service Award at Northwestern University Department Microbiology-Immunology [T32 AI007476], the American Heart Association [0425607Z], and NIH Research Supplements to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research [HL069630]), and to S.F.-P. (NRSA F30 HL094042 and American Heart Association [0810102Z]).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.A.T. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper, H.L. and S.F.-P. performed experiments; K.H. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and A.W. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pamela A. Tamez, Center for Rare and Neglected Diseases, University of Notre Dame, 103 Galvin Life Sciences, South Bend, IN 46556; e-mail: ptamez@nd.edu; or Amittha Wickrema, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, Chicago, IL 60637; e-mail: awickrem@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu; or Kasturi Haldar, Center for Rare and Neglected Diseases, University of Notre Dame, 103 Galvin Life Sciences, South Bend, IN 46556; e-mail: khaldar@nd.edu.

![Figure 2. Characterization of human erythroblast maturation by susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection and by transcriptional response. (Ai) Percentage of day 5, 10, and 16 erythroblasts infected by Plasmodium falciparum. No infection is detected in pro-/basophilic erythroblasts (day 5). At day 10, when the population is largely at the polychromatic stage a few early orthochromatic cells are detected that can also be infected. (ii) Infection is seen in early/mid (day 14, ■) and late (day 16, ■) orthochromatic erythroblasts (N indicates nucleated; and E, enucleated), whereas only minor infection can be detected in polychromatic erythroblasts (day 10). represent the percentage of nucleated/enucleated cells in the population, and ■ represent the proportion infected (marked with numbers) in each subset. Under these conditions, in cultures containing only mature erythrocytes we detect 60% infection. Error bars indicate SEM; n = 3 for day 10; n = 3 for day 14; n = 2 for day 16. (B) Brightfield images of Giemsa-stained infected erythroblast cells at 22 hours after invasion (hpi indicates hours of intracellular parasite growth; day 10, i; day 14, iii; day 16, v) and at 40 hpi (day 10, ii; day 14, iv; day 16, vi). On day 10 at 22 hpi, a few cells contain ring-stage parasites (i, ). Judging from staining of condensed nuclei, these cells are at the early orthochromatic stage. At 40 hpi, no mature schizonts are seen, but ring vacuoles (ii, ) may remain. On day 14, at 22 hpi, more than half the cells show rings (iii, ), which fail to mature to schizonts, but ring vacuoles (iv, ) are prominently detected. Half of these cells become vacuolated by 40 hpi (iv, []). On day 16, at 22 hpi and 40 hpi, respectively, ring-stage parasites (v, ) and schizont-stage parasites with hemozoin crystals (vi, ) are evident in nucleated, late orthochromatic erythroblasts. Photomicrographs were taken by light microscopy with a Zeiss Axioskop upright microscope and Nuance spectral camera/unmixing system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation) using a 100× objective. Scale represents 5 μm. (C) Transcriptional profile of day 14 versus day 10 erythroblasts. Up-regulated transcripts are denoted with red squares; down-regulated, with blue diamonds; unchanged, with gray crosses. As expected, hemoglobins a and b were highly transcribed (spot 1, purple asterisks), erythrocyte protein band 4.1 (epb41) was up-regulated, and adducin 2 (add2) was down-regulated (inset, black squares, spots 12 and 13, respectively), suggesting assembly of the cytoskeleton was still in progress. Beta-actin (actb, spot 2), glycophorins (gypc spot 3, gypa spot 4, gypb spot 6), spectrin (spta1 spot 5, sptb spot 9), ankyrin (ank1 spot 7), band 3 (slc4a1 spot 8), Duffy (darc spot 10), and adducin 3 (add3 spot 11) are all expressed but show no significant change (fold change < 2, black squares). In addition erythropoietin receptor (epor spot 14, inset) transcript is reduced relative to transferrin receptor (cd71 spot 15, green circles) but nonetheless detectable. Bcl2-like 1 (bcl2l1 or bcl-xL; spot 18), a marker for terminal stages of erythropoiesis,10 is up-regulated 2.6-fold (P = .006, q = 0.005). In addition, it appears early orthochromatic cells are exiting the cell cycle because both cyclins D3 and E2 (ccnd3, ccne2; spots 16 and 17, respectively) are down-regulated ∼ 3-fold compared with polychromatic cells (P = .002, q = 0.003 and P = .02, q > 0.007, respectively). (D) Diagram displaying differential susceptibility of erythroblasts to P falciparum infection. Whereas orthochromatic cells can support parasite entry, only enucleating erythroblasts/nascent reticulocytes support intracellular parasite growth.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/17/10.1182_blood-2009-07-231894/4/m_zh89990943570002.jpeg?Expires=1769161907&Signature=idAXAJXs2t1pntCaXGOL~xAw7e-KlBXUTT~lX~-ahSkfd9cEhFD8gp9O~tv-S00ZHR9BGQE9KAZg-2R2HyXZFhIUTLFJPn4N66g4a4QlcKIVO093cXt2UstjcOUzGOtcSAJO7XtzGHaHxlhI7xhxf5XDB1h5w0He7s2Z4TtVobuBjOmbT4T34aQ4CMK7N~dAdJ6fqzwt15y35hz5manVQXVZR6cV6HwnJpv5CVq8J5RTOQhAhkkRPRXCTZgnt3u1y6XI71IeEM2JXvdwQ7-F~2W3Ae-7gfQIiPsj7-0oedihuqRG6PHhxq5xLibUu5XcTQlOEYH5iOjjeeISzy-Pyg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal