In this issue of Blood, Eichhorst and colleagues report on the results of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) CLL5 study.1 The importance of this randomized trial is that it restricted enrollment to more elderly patients who are the most representative of the population who have this disease.

There have been major advances reported over the past decade in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with chemo-immunotherapy approaches now the treatment of choice.2 A decade ago, chlorambucil was the treatment of choice. However, CLL is a disease of the elderly with a median age at diagnosis of 72 years, and almost 70% of CLL patients are older than 65 years at the time of diagnosis. These more elderly patients have been vastly underrepresented in clinical trials. Moreover, elderly patients may not have sufficiently good performance status to tolerate the aggressive chemo-immunotherapy approaches. There were elderly patients included in a randomized clinical trial in the United Kingdom comparing treatment with chlorambucil, fludarabine, or fludarabine and chlorambucil. These patients appeared to tolerate combination chemotherapy.3 However, there was considerable patient selection bias here, considering that physicians must have been prepared to treat these patients with combination chemotherapy so only patients with sufficiently good performance status to tolerate the more aggressive regimens were enrolled. Of note, among the patients in the United Kingdom who were older than 70 years, there was also no improved outcome for those patients receiving fludarabine alone. The advance in the CLL5 study is that both study arms were deemed tolerable for the intended patient population and therefore the results are likely to be more applicable to the more elderly patients seen in practice. This multicenter phase 3 trial enrolled patients older than 65 years and compared first-line therapy with fludarabine to chlorambucil. Chlorambucil was the first effective agent used in the treatment of CLL. The drug has largely fallen out of fashion in the United States but continues to be widely used in Europe. A total of 193 patients with a median age of 70 years were randomized to receive intravenous fludarabine or oral chlorambucil. The results demonstrated that, although patients receiving fludarabine had a higher response rate than those receiving chlorambucil, there was no difference in progression-free survival or overall survival. In fact, as shown in Figure 2 of the article, median survival was 18 months longer for those receiving chlorambucil, although the differences did not achieve statistical significance.1 The results demonstrate no clinical benefit for fludarabine over chlorambucil as first-line therapy of elderly CLL patients.

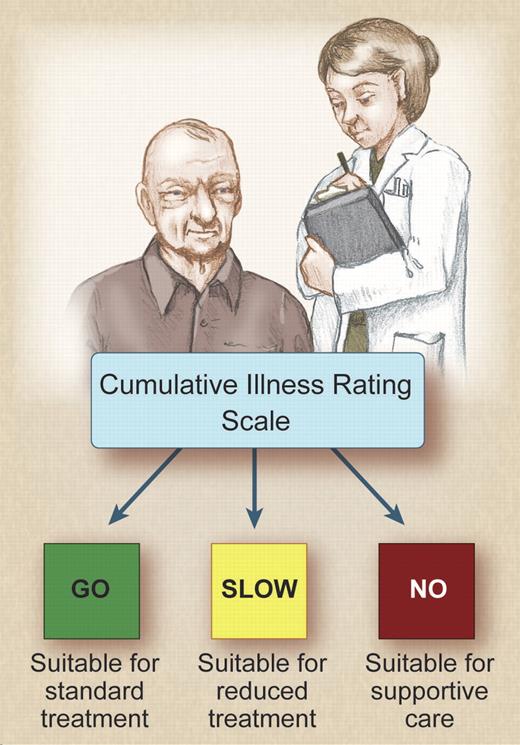

It is clear that the performance status is more important than the chronological age of the patient. It is extremely important to assess the patient's comorbidities and fitness before recommending treatment. Several different methods are used to assess the fitness of patients. The International Society of Geriatric Oncology Chemotherapy Taskforce published consensus recommendations on chemotherapy in the elderly.4 The authors concluded that there is a lack of evidence-based data with regard to chemotherapy and that consensus recommendations had to be made on the basis of inadequate data. One of the systems that has been widely used by geriatricians but not by oncologists is the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS), which assesses whether comorbidities exist in different organ systems. The German CLL study group has taken a lead in this respect and has incorporated physiologic assessment to guide the choice of chemotherapy in any given patient. The group defines fit patients with no comorbidities who can tolerate combination chemo-immunotherapies at full dose as “go-go” patients. Patients who have reduced performance scores, and who may tolerate dose-reduced monotherapy, are termed “slow-go” patients. The relationship of comorbidity and drug pharmacokinetics is unknown and requires further study. The basis for enrollment in ongoing GCLLSG studies is not the age of the patient, but whether they fit into the “go-go” or “slow-go” categories as outlined in the figure.

The cumulative illness rating score can be used to determine the appropriate chemotherapy treatment in CLL. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

The cumulative illness rating score can be used to determine the appropriate chemotherapy treatment in CLL. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

Currently, the disease remains incurable using standard treatment approaches. There is no justification in offering therapy earlier in their clinical course; a meta-analysis of more than 2000 patients enrolled in previous trials demonstrated no survival advantage for early treatment versus a “watch and wait” approach.5 It should be noted that these studies were all performed using alkylating agents. The aim of treatment is to improve the quality of life of patients. Measures of quality of life are critical in interpreting clinical trials, particularly in the elderly. A quality-of-life assessment was incorporated into the CLL5 study, although it is disappointing that a minority of patients completed it. If more elderly patients are to have improved outcome, then alternative approaches have to be taken.

At first glance, it would appear that the results of this study put us back a decade by suggesting that chlorambucil is the optimal treatment for elderly frail patients with CLL. It is extremely important that appropriate clinical studies that address the needs of this previously neglected patient population are finally being designed. Ongoing clinical trials focusing on the more elderly frail patients are assessing whether the addition of monoclonal antibodies including rituximab, ofatumomab, and newer chemotherapeutic agents result in improvement compared with chlorambucil alone. Additional agents being assessed in clinical trials in this patient population include bendamustine alone and in combination with rituximab, lenalidomide, and ABT263.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.G.G. receives funding from the National Cancer Institute to the CLL Research Consortium (CA81538) and has received honoraria from Riche, GSK, and Celgene for work on advisory boards and for lecturing. ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health