Abstract

Platelet activation and aggregation at sites of vascular injury are essential for primary hemostasis, but are also major pathomechanisms underlying myocardial infarction and stroke. Changes in [Ca2+]i are a central step in platelet activation. In nonexcitable cells, receptor-mediated depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores triggers Ca2+ entry through store-operated calcium (SOC) channels. STIM1 has been identified as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–resident Ca2+ sensor that regulates store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in immune cells and platelets, but the identity of the platelet SOC channel has remained elusive. Orai1 (CRACM1) is the recently discovered SOC (CRAC) channel in T cells and mast cells but its role in mammalian physiology is unknown. Here we report that Orai1 is strongly expressed in human and mouse platelets. To test its role in blood clotting, we generated Orai1-deficient mice and found that their platelets display severely defective SOCE, agonist-induced Ca2+ responses, and impaired activation and thrombus formation under flow in vitro. As a direct consequence, Orai1 deficiency in mice results in resistance to pulmonary thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, and ischemic brain infarction, but only mild bleeding time prolongation. These results establish Orai1 as the long-sought platelet SOC channel and a crucial mediator of ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Introduction

At sites of vascular injury the subendothelial extracellular matrix (ECM) is exposed to the flowing blood and triggers sudden platelet activation and the formation of a fibrin-containing thrombus. This process is essential to prevent excessive posttraumatic blood loss, but if it occurs at sites of atherosclerotic plaque rupture it can also lead to vessel occlusion and the development of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, which are among the leading causes of mortality and severe disability in industrialized countries.1,2 Therefore, the inhibition of platelet activation has become an important strategy to prevent or treat such acute ischemic events.3 Platelet activation can occur through different signaling pathways that culminate in the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms and production of diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3). IP3 binds its receptors on the membrane of the intracellular Ca2+ stores and mediates Ca2+ release into the cytosol. In platelets, the dense tubular system, referred to as sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), is thought to be the major Ca2+ store. The resulting decline in Ca2+ store content in turn triggers a sustained influx of extracellular Ca2+ by a mechanism known as store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE).4,5 Although SOCE has pharmacologically been well defined for more than a decade, not much was known about the underlying molecular machinery until recently, when stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) was identified as a sarco/endoplasmic (SR/ER)–store calcium sensor that controls SOCE in T cells and mast cells.6–9 Shortly after that, we have shown that STIM1-mediated SOCE is critical for platelet function,10 mainly by contributing to stable thrombus formation under flow conditions.11 However, the identity of the store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channel in platelets has remained elusive. Members of the canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) family, most notably TRPC1, have been proposed to contribute to SOCE in platelets,12–14 but the overall significance of this contribution has remained unclear because the expression rates of TRPCs in platelets are very low and mice lacking TRPC1 have no detectable defect in SOCE.15

The 4 transmembrane protein Orai1 (also called CRACM1) has been identified as an essential component of SOCE in human T cells and mast cells.16–20 Orai1 is also expressed in platelets and might be involved in SOCE.21 In the current study, we confirm that Orai1 is strongly expressed in human and mouse platelets. Analysis of Orai1−/− mice revealed an essential role of the channel in platelet SOCE and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Mice

Animal studies were approved by the Bezirksregierung of Unterfranken (Würzburg, Germany). Orai1−/− mice were generated as described by Vig et al.18 Briefly, embryonic stem (ES) cell clone (XL922) was purchased from BayGenomics (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) and microinjected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts to generate Orai1 chimeric mice. After germline transmission, heterozygous and knockout animals were genotyped by Southern blot and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using mouse tail DNA. Homologous recombinant and wild-type alleles were detected by external probe that is located in upstream region of exon1. External probe was amplified by PCR (ExtpFor: 5′-gctaggggaatctcagaaac-3′; ExtpRev: 5′-catccgaggtcacctctggg-3′). For PCR-based genotyping, geo-specific forward and reverse primers were used (GeoF: 5′-TTATCGATGAGCGTGGTGGTTATG-3′; GeoR: 5′-GCGCGTACATCGGGCAAATAATATC-3′).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras.

Five- to 6-week-old C57Bl/6 female mice were irradiated with a single dose of 10 Gy, and bone marrow cells from wild-type or Orai1−/− mice were injected intravenously into the irradiated mice (4 × 106 cells/mouse). All recipient animals received acidified water containing 2 g/L neomycin sulfate for 6 weeks after transplantation.

RT-PCR analysis

Human and murine platelet mRNA was isolated using Trizol reagent and detected by reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Primers were used as previously described.22

Chemicals and antibodies

The following were used according to the regulation of the local authorities: anesthetic drugs: medetomidine (Pfizer, Karlsruhe, Germany), midazolam (Roche Pharma, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany), and fentanyl (Janssen-Cilag, Neuss, Germany); and antagonists: atipamezol (Pfizer), flumazenil, and naloxon (both from Delta Select, Dreieich, Germany). ADP (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany), U46619 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), thrombin (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), collagen (Kollagenreagent Horm; Nycomed, Munich, Germany), and thapsigargin (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) were purchased. Monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE), or DyLight-488, were from Emfret Analytics (Würzburg, Germany). Anti-Orai1 antibodies were from ProSci (Poway, CA) and Protein Tech Group (Chicago, IL).

Intracellular calcium measurements

Platelets isolated from blood were washed, suspended in Tyrode buffer without calcium, and loaded with fura-2/AM (5 μM) in the presence of Pluronic F-127 (0.2 μg/mL; Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After labeling, platelets were washed once and resuspended in Tyrode buffer containing no or 1 mM Ca2+. Stirred platelets were activated with agonists, and fluorescence was measured with a PerkinElmer LS 55 fluorimeter (Waltham, MA). Excitation was alternated between 340 and 380 nm, and emission was measured at 509 nm. Each measurement was calibrated using Triton X-100 and EGTA.

Platelet aggregometry

Changes in light transmission of a suspension of washed platelets (200 μL with 0.5 × 106 platelets/μL) were measured in the presence of 70 μg/mL human fibrinogen. Transmission was recorded on a Fibrintimer 4 channel aggregometer (APACT Laborgeräte und Analysensysteme, Hamburg, Germany) over 10 minutes, and was expressed in arbitrary units with buffer representing 100% transmission.

Flow cytometry

Heparinized whole blood was diluted 1:20 with modified Tyrode-HEPES buffer (134 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 7.0) containing 5 mM glucose, 0.35% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 1 mM CaCl2. For glycoprotein expression and platelet count, blood samples were incubated with appropriate fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies for 15 minutes at room temperature and analyzed on a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). For activation studies, blood samples were washed twice with modified Tyrode-HEPES buffer, incubated with agonist for 15 minutes, stained with fluorophore-labeled antibodies for 15 minutes at room temperature, and then analyzed.

Adhesion under flow conditions

Rectangular coverslips (24 × 60 mm) were coated with 0.2 mg/mL fibrillar type I collagen (Nycomed) for 1 hour at 37°C and blocked with 1% BSA. Heparinized whole blood was labeled with a Dylight-488 conjugated anti-GPIX Ig derivative (0.2 μg/mL) and perfused through transparent flow chambers with a slit depth of 50 μm and equipped with collagen-coated (200 μg/mL) coverslips. Perfusion was carried out at room temperature using a pulse-free pump at high (1700 s−1) shear rates. During perfusion, microscopic phase-contrast images were recorded in real time. The chambers were rinsed by a 10-minute perfusion with HEPES buffer, pH 7.45, at the same shear, and phase-contrast and fluorescent pictures were recorded from at least 5 different microscopic fields (40×/0.75 NA objectives; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). Image analysis was performed off-line using Metavue software (Visitron, Munich, Germany). Thrombus formation was expressed as the mean percentage of total area covered by thrombi, and as the mean integrated fluorescence intensity per square millimeter.

Bleeding time

Mice were anesthetized and a 3-mm segment of the tail tip was removed with a scalpel. Tail bleeding was monitored by gently absorbing blood with filter paper at 20-second intervals, without making contact with the wound site. When no blood was observed on the paper, bleeding was determined to have ceased. Experiments were stopped after 20 minutes.

Aorta occlusion model

A longitudinal incision was used to open the abdominal cavity of anesthetized mice and expose the abdominal aorta. An ultrasonic flow probe was placed around the vessel and thrombosis was induced by a single firm compression with a forceps. Blood flow was monitored until complete occlusion occurred; otherwise experiments were stopped manually after 30 minutes.

Pulmonary thromboembolism model

Anesthetized mice received a mixture of collagen (150 μg/kg) and epinephrine (60 μg/kg) intravenously. Mice that were alive 30 minutes after challenge were considered survivors. In parallel groups, the lungs were harvested at the indicated time points and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Intravital microscopy of thrombus formation in FeCl3-injured mesenteric arterioles

Four weeks after bone marrow transplantations, chimeras were anesthetized, and the mesentery was exteriorized through a midline abdominal incision. Arterioles (35-60 μm diameter) were visualized with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (10×/0.3 NA objective) (Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany) equipped with a 100-W HBO fluorescent lamp source, and a CoolSNAP-EZ camera (Visitron). Digital images were recorded and analyzed off-line using Metavue software. Injury was induced by topical application of a 3-mm2 filter paper saturated with FeCl3 (20%) for 10 seconds. Adhesion and aggregation of fluorescently labeled platelets (Dylight-488–conjugated anti-GPIX Ig derivative) in arterioles were monitored for 40 minutes or until complete occlusion occurred (blood flow stopped for > 1 minute).

MCAO model

Experiments were conducted on 10- to 12-week-old Orai1−/− or control chimeras according to published recommendations for research in mechanism-driven basic stroke studies.23 Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) was induced under inhalation anesthesia using the intraluminal filament (6021PK10; Doccol, Redlands, CA) technique.24 After 60 minutes, the filament was withdrawn to allow reperfusion. For measurements of ischemic brain volume, animals were killed 24 hours after induction of tMCAO and brain sections were stained with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma-Aldrich). Brain infarct volumes were calculated and corrected for edema as described.

Neurologic testing.

Assessment of brain infarcts by MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed 24 hours and 5 days after stroke on a 1.5 T unit (Vision; Siemens, Munich, Germany) under inhalation anesthesia. A custom-made dual-channel surface coil was used for all measurements (A063HACG; Rapid Biomedical, Rimpar, Germany). The MR protocol included a coronal T2-w sequence (slice thickness, 2 mm) and a coronal T2-w gradient echo constructed interference in steady state (CISS) sequence (slice thickness, 1 mm). MR images were transferred to an external workstation (Leonardo; Siemens) for data processing. Visual analysis of infarct morphology and intracerebral hemorrhage was performed in a blinded manner.

Histology

Formalin-fixed samples embedded in paraffin (Histolab Products AB, Gotheburg, Sweden) were cut into 4-μm–thick sections and mounted. After removal of paraffin, tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistics

Results from at least 3 experiments per group are presented as mean plus or minus SD. Differences between wild-type and Orai1−/− groups were assessed by 2-tailed Student t test.

MCAO model.

Results are presented as mean plus or minus SD. Infarct volumes and functional data were tested for Gaussian distribution with the D'Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test and then analyzed using the 2-tailed Student t test. For statistical analysis, PrismGraph 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Using RT-PCR analysis, we found Orai1 to be the predominant member of the Orai family present in human platelets at mRNA level; however, very faint bands of Orai2 and Orai3 were also observed. Western blot analysis of human platelet lysates using 2 different antibodies demonstrated robust expression of Orai1, indicating that the channel might have a role in Ca2+ homeostasis in those cells (Figure 1A). Both antibodies detected the protein as a single band at an apparent molecular weight of approximately 50 kDa, indicating that Orai1 is significantly glycosylated in platelets, most likely at the consensus N-linked glycosylation site, N223, as previously shown in HEK293 cells.19

Orai1 is the platelet SOC channel. (A) RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of human platelets. Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 were assessed with the primer pairs described in Takahashi et al,22 and Western blot was performed using an antibody from ProSci. (B) Wild-type and Orai1−/− littermates (3 weeks old). (C) Body weights of wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice. Error bars represent plus or minus SD. (D) RT-PCR analyses of platelet and thymocyte mRNA from wild-type (+/+), original Orai1−/− (−/−), and Orai1−/− bone marrow chimera (−/− BMc) mice. Orai1-, Orai2-, and Orai3-specific forward and reverse primers were used22 ; actin served as control. (E) Fura-2–loaded platelets were stimulated with 5 μM TG for 10 minutes, followed by addition of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ and monitoring of [Ca2+]i. Representative measurements (left) and maximal Δ[Ca2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group) before and after addition of 1 mM Ca2+ (right) are shown. □ represents Stim1−/− platelets.

Orai1 is the platelet SOC channel. (A) RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of human platelets. Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 were assessed with the primer pairs described in Takahashi et al,22 and Western blot was performed using an antibody from ProSci. (B) Wild-type and Orai1−/− littermates (3 weeks old). (C) Body weights of wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice. Error bars represent plus or minus SD. (D) RT-PCR analyses of platelet and thymocyte mRNA from wild-type (+/+), original Orai1−/− (−/−), and Orai1−/− bone marrow chimera (−/− BMc) mice. Orai1-, Orai2-, and Orai3-specific forward and reverse primers were used22 ; actin served as control. (E) Fura-2–loaded platelets were stimulated with 5 μM TG for 10 minutes, followed by addition of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ and monitoring of [Ca2+]i. Representative measurements (left) and maximal Δ[Ca2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group) before and after addition of 1 mM Ca2+ (right) are shown. □ represents Stim1−/− platelets.

To directly test the function of Orai1 in platelet SOCE and activation, we generated Orai1-null (Orai1−/−) mice through disruption of the Orai1 gene by insertion of a gene-trap cassette into intron 2 as recently independently reported by Vig and coworkers.17 Mice heterozygous for the Orai1-null mutation developed normally, whereas approximately 60% of the Orai1−/− mice died shortly after birth for unknown reasons. Surviving Orai1−/− animals developed significantly slower, reaching only approximately 60% of the body weight of their littermates at 2 weeks of age (Figure 1B,C) and showing still very high mortality, as all animals died at latest 4 weeks after birth. RT-PCR analysis revealed the presence of wild-type Orai1 mRNA message in control but not in Orai1−/− platelets (Figure 1D). Western blot detection of Orai1 was not possible, as no antibodies are available that recognize the murine protein. Similar to human platelets, low levels of Orai2 or Orai3 transcripts were detectable in both wild-type and Orai1−/− platelets, whereas all 3 isoforms were strongly detectable in wild-type thymocytes22 (Figure 1D). These results show that Orai1 is highly expressed in human platelets and suggest that Orai1 is also the dominant member of the Orai family in mouse platelets. Therefore, we analyzed Orai1−/− platelets in more detail.

Due to the early lethality and growth retardation of Orai1−/− mice, all further studies were performed with lethally irradiated wild-type mice that received a transplant of Orai1−/− or control bone marrow cells. Four weeks after transplantation, both groups of mice had normal platelet counts (Table 1) and RT-PCR confirmed the virtually complete absence of Orai1 mRNA in platelets from Orai1−/− chimeras (Figure 1D). Furthermore, mean platelet volumes (MPVs) and the expression of prominent surface glycoprotein receptors were similar between wild-type and Orai1−/− chimeras (data not shown), as were the main hematologic and clotting parameters (Table 1). Together, these results demonstrate that megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation occur independently of Orai1.

Hematology and hemostasis in Orai1−/− chimeras

| . | Orai1+/+ . | Orai1−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| Platelets | 8036 ± 215 | 8888 ± 153 |

| MPV, fL | 5.27 ± 0.12 | 5.35 ± 0.19 |

| Erythrocytes | 9150 ± 198 | 8718 ± 291 |

| HCT, % | 45.9 ± 0.99 | 42.6 ± 1.2 |

| aPTT, s | 38.7 ± 6.8 | 37.7 ± 2.9 |

| QT, % | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 0.7 |

| INR | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.04 |

| . | Orai1+/+ . | Orai1−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| Platelets | 8036 ± 215 | 8888 ± 153 |

| MPV, fL | 5.27 ± 0.12 | 5.35 ± 0.19 |

| Erythrocytes | 9150 ± 198 | 8718 ± 291 |

| HCT, % | 45.9 ± 0.99 | 42.6 ± 1.2 |

| aPTT, s | 38.7 ± 6.8 | 37.7 ± 2.9 |

| QT, % | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 9.8 ± 0.7 |

| INR | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.04 |

Platelet and erythrocyte counts per nanoliter and coagulation parameters for control and Orai1−/− chimeras. Values given are mean values plus or minus SD of 5 mice for each genotype.

MPV indicates mean platelet volume; HCT, hematocrit; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; QT, quick test; and INR, international normalized ratio.

To test the role of Orai1 in SOCE, we performed intracellular calcium measurements in Orai1−/− and control platelets. For this, Fura-2–loaded cells were treated with the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) in calcium-free buffer followed by addition of extracellular calcium, and changes in [Ca2+]i were monitored (Figure 1E left panel). Store release evoked by TG was comparable between wild-type and Orai1−/− platelets (78.8 ± 25.7 nM and 62 ± 13.4 nM, respectively; P = .17; n = 6), whereas it was reduced in Stim1−/− platelets (42.3 ± 7 nM; P = .005; n = 6) as reported previously.11 However, the subsequent SOCE was almost completely blocked in the absence of Orai1 (1438 ± 466 nM vs 155 ± 44 nM; P < .001; n = 6; Figure 1E right panel) and this defect was similar to that seen in Stim1−/− platelets (Figure 1E right panel and Varga-Szabo et al11 ). These results establish Orai1 as the principal SOC channel in platelets and show that its loss cannot be functionally compensated by Orai2 or Orai3. Furthermore, these data indicate that Orai1, in contrast to STIM1, is not required for proper store content regulation in platelets.

To investigate the impact of the Orai1-null mutation on agonist-induced Ca2+ responses, we measured the changes in [Ca2+]i upon platelet activation with different agonists (Figure 2A). In agreement with the results from the TG experiments, store release in response to ADP, thrombin (Figure 2C), and the stable TxA2 analog U46619 (not shown), which act on Gq/PLCβ-coupled receptors, was unaltered in Orai1−/− platelets compared with wild type. Furthermore, only a very mild reduction was seen in response to collagen-related peptide (CRP), a specific ligand of the activating collagen receptor glycoprotein VI (GPVI) that triggers tyrosine phosphorylation cascades downstream of the receptor-associated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) culminating in the activation of PLCγ2 (69.6 ± 15.9 nM vs 50.5 ± 14.4 nM; P < .05; n = 6; Figure 2A,B). These results again differ from those obtained with Stim1−/− platelets where store release was strongly reduced in response to all of these agonists, further indicating a direct role for STIM1 in store content regulation. When the experiment was performed in the presence of extracellular calcium, however, a pronounced Ca2+ influx was detectable in wild-type platelets that was dramatically reduced, but not abrogated, in Orai1−/− platelets (Figure 2A,B) and thereby similarly defective as previously seen in Stim1−/− platelets.11 Together, these results demonstrate that Orai1 is essential for efficient agonist-induced Ca2+ entry in platelets but that it is not required for store content regulation in those cells. As a consequence, due to normal store release, Orai1−/− platelets reach significantly higher cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations in response to all major agonists than Stim1−/− platelets, despite equally defective SOCE.

Defective agonist-induced Ca2+ response and aggregate formation under flow in Orai1−/− platelets. Fura-2–loaded wild-type (black line) or Orai1−/− (gray line) platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), or CRP (10 μg/mL) in calcium-free medium or in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM), and [Ca2+]i was monitored. Representative measurements (A) and maximal Δ[Ca 2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group; B) are shown. (C) Impaired aggregation of Orai1−/− platelets (gray lines) in response to collagen, but not ADP and thrombin. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of αIIbβ3 integrin activation (left panel) and degranulation-dependent P-selectin exposure (right panel) in response to thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), CRP (10 μg/mL), and CVX (1 μg/mL). Results are means plus or minus SD of 6 mice per group. (E) Orai1−/− platelets in whole blood fail to form stable thrombi when perfused over a collagen-coated (0.2 mg/mL) surface at a shear rate of 1700 s−1. (Top) Representative phase contrast images. (Bottom) Mean surface coverage (left) and relative platelet deposition as measured by the integrated fluorescent intensity (IFI) per square millimeter (right) plus or minus SD (n = 4). Bar represents 30 μm. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Defective agonist-induced Ca2+ response and aggregate formation under flow in Orai1−/− platelets. Fura-2–loaded wild-type (black line) or Orai1−/− (gray line) platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), or CRP (10 μg/mL) in calcium-free medium or in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM), and [Ca2+]i was monitored. Representative measurements (A) and maximal Δ[Ca 2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group; B) are shown. (C) Impaired aggregation of Orai1−/− platelets (gray lines) in response to collagen, but not ADP and thrombin. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of αIIbβ3 integrin activation (left panel) and degranulation-dependent P-selectin exposure (right panel) in response to thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), CRP (10 μg/mL), and CVX (1 μg/mL). Results are means plus or minus SD of 6 mice per group. (E) Orai1−/− platelets in whole blood fail to form stable thrombi when perfused over a collagen-coated (0.2 mg/mL) surface at a shear rate of 1700 s−1. (Top) Representative phase contrast images. (Bottom) Mean surface coverage (left) and relative platelet deposition as measured by the integrated fluorescent intensity (IFI) per square millimeter (right) plus or minus SD (n = 4). Bar represents 30 μm. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

To test the functional consequences of the defective SOCE, we first performed in vitro aggregation studies. All agonists induced a comparable activation-dependent change from discoid to spherical shape in control and Orai1−/− platelets, which can be seen in aggregometry as a short decrease in light transmission following the addition of agonists. However, Orai1−/− platelets aggregated normally in response to the G-protein–coupled agonists ADP, thrombin (Figure 2C), and U46619 (not shown); the responses to collagen, CRP (Figure 2C), and the strong GPVI-specific agonist convulxin (CVX; not shown) were diminished at low agonist concentrations, whereas the defect was overcome at intermediate or high agonist concentrations. This selective impairment in GPVI-ITAM–mediated activation was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of integrin αIIbβ3 activation and degranulation-dependent P-selectin surface exposure. As shown in Figure 2D, Orai1−/− platelets displayed markedly reduced responses to CRP or CVX (P < .001), even at high concentrations, whereas the responses to ADP and thrombin were not affected. As expected, the weak agonist ADP failed to induce P-selectin surface expression in wild-type and Orai1−/− platelets. These results demonstrate that loss of Orai1-mediated SOCE specifically impairs GPVI-induced integrin activation and degranulation, whereas G-protein–coupled agonists, despite defective [Ca2+]i signaling, are still able to induce unaltered cellular activation in these assays. Similar observations have been made with Stim1−/− platelets.11

Under physiological conditions, platelet adhesion and aggregation occur in the flowing blood where high shear forces strongly influence these platelet functions. To test the significance of Orai1-mediated SOCE in thrombus formation under flow, we studied platelet adhesion to collagen in a whole-blood perfusion assay at high arterial shear rates (1700 s−1). Wild-type platelets rapidly adhered to collagen and consistently formed stable 3-dimensional thrombi that covered 43.6% plus or minus 6.1% of the total surface area at the end of the 4-minute run time (Figure 2E). In sharp contrast, platelets from Orai1−/− mice could barely form 3-dimensional thrombi, and the overall surface coverage was reduced by approximately 60% compared with the control (17.6 ± 5.2; P < .001; n = 5) (Figure 2E). The defect in 3-dimensional thrombus formation became even more evident when the relative thrombus volume was measured and found to be reduced by approximately 95% (33 × 109 ± 5.8 × 109 vs 2.1 × 109 ± 1.8 × 109 integrated fluorescence intensity [IFI]/mm2; P < .001; n = 5) (Figure 2E). These results show that Orai1-mediated SOCE is essential for the formation of stable 3-dimensional thrombi under high shear flow conditions in vitro.

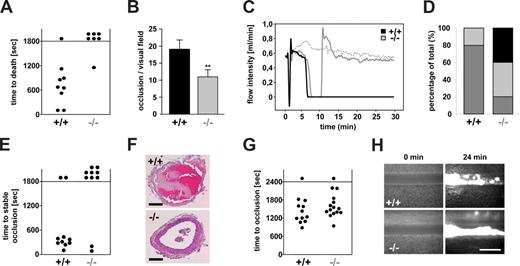

To assess the significance of Orai1-mediated SOCE for platelet function in vivo, wild-type and Orai1−/− chimeras were intravenously injected with collagen/epinephrine (150 μg/kg; 60 μg/kg), which causes lethal pulmonary thromboembolism.26 Whereas all but one wild-type chimeras died within 20 minutes after injection due to asphyxia, 6 of 7 Orai1−/− chimeras survived the challenge (Figure 3A). This protection was based on reduced platelet activation, as platelet counts 30 minutes after challenge (or shortly before death in the wild-type animals) were significantly higher in Orai1−/− compared with wild-type chimeras (5.24 ± 0.8 × 105/μL in Orai1−/− vs 2.16 ± 0.9 × 105/μL in wild-type; P < .005; n = 4), and the number of obstructed pulmonary vessels was approximately 50% less in the mutant animals (11 ± 2 vs 19 ± 3 per histologic section; P < .005; n = 4) (Figure 3B).

Reduced thrombus stability of Orai1−/− platelets in vivo. (A,B) Lethal pulmonary embolization after injection of collagen and epinephrine in anesthetized wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice. (A) Time to death through asphyxia. Each symbol represents one individual. (B) Occluded arteries in the harvested lungs per visual field. **P < .01. (C-F) Mechanical injury of the abdominal aorta of wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice was performed and blood flow was monitored with a Doppler flowmeter. Representative flow measurements (C), percentage distribution of irreversible occlusion ( ), unstable occlusion (

), unstable occlusion ( ) and no occlusion (■) (D), time to final occlusion (each symbol represents one individual) (E), and representative cross-sections of the aorta 30 minutes after injury (F) are shown. Bars represent 100 μm. (G,H) FeCl3-induced chemical injury of small mesenteric arteries from wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) chimeras. (G) Time to occlusion. Each dot represents one individual. (H) Representative fluorescent images before and 24 minutes after injury. Bar represents 50 μm.

) and no occlusion (■) (D), time to final occlusion (each symbol represents one individual) (E), and representative cross-sections of the aorta 30 minutes after injury (F) are shown. Bars represent 100 μm. (G,H) FeCl3-induced chemical injury of small mesenteric arteries from wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) chimeras. (G) Time to occlusion. Each dot represents one individual. (H) Representative fluorescent images before and 24 minutes after injury. Bar represents 50 μm.

Reduced thrombus stability of Orai1−/− platelets in vivo. (A,B) Lethal pulmonary embolization after injection of collagen and epinephrine in anesthetized wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice. (A) Time to death through asphyxia. Each symbol represents one individual. (B) Occluded arteries in the harvested lungs per visual field. **P < .01. (C-F) Mechanical injury of the abdominal aorta of wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice was performed and blood flow was monitored with a Doppler flowmeter. Representative flow measurements (C), percentage distribution of irreversible occlusion ( ), unstable occlusion (

), unstable occlusion ( ) and no occlusion (■) (D), time to final occlusion (each symbol represents one individual) (E), and representative cross-sections of the aorta 30 minutes after injury (F) are shown. Bars represent 100 μm. (G,H) FeCl3-induced chemical injury of small mesenteric arteries from wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) chimeras. (G) Time to occlusion. Each dot represents one individual. (H) Representative fluorescent images before and 24 minutes after injury. Bar represents 50 μm.

) and no occlusion (■) (D), time to final occlusion (each symbol represents one individual) (E), and representative cross-sections of the aorta 30 minutes after injury (F) are shown. Bars represent 100 μm. (G,H) FeCl3-induced chemical injury of small mesenteric arteries from wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) chimeras. (G) Time to occlusion. Each dot represents one individual. (H) Representative fluorescent images before and 24 minutes after injury. Bar represents 50 μm.

Next we assessed arterial thrombus formation in vivo in a model of arterial thrombosis where the abdominal aorta is mechanically injured and blood flow is monitored by an ultrasonic perivascular Doppler flowmeter. In this model, thrombus formation is triggered predominantly by collagen and thus occurs in an ITAM/PLCγ2-dependent manner.27 Whereas all wild-type vessels occluded, blood flow stopped only in 6 of 10 Orai1−/− chimeras. However, in 4 of these 6 vessels the thrombi embolized, and consequently normal blood flow was found in 8 of 10 Orai1−/− chimeras at the end of the 30-minute observation period (Figure 3C-F). In contrast, all vessels in wild-type chimeras occluded (Figure 3C,D), and only 2 of 10 vessels embolized and remained open (Figure 3D-F). Next, the mice were tested in a model of FeCl3-induced injury of mesenteric arterioles where thrombus formation is highly thrombin dependent28 and GPVI/FcRγ-chain deficiency is only partially protective (D.V.-S. and B.N., unpublished observations, June 2008). Interestingly, 14 of 15 Orai1−/− chimeras were able to form occlusive thrombi in this model, and the process showed similar kinetics compared with the wild-type controls (11/12 vessels occluded) (Figure 3G,H). Together, these results demonstrate that Orai1-mediated SOCE is required for the stabilization of platelet-rich thrombi at sites of arterial injury under conditions where the process in driven mainly by GPIb-GPVI-ITAM–dependent mechanisms.

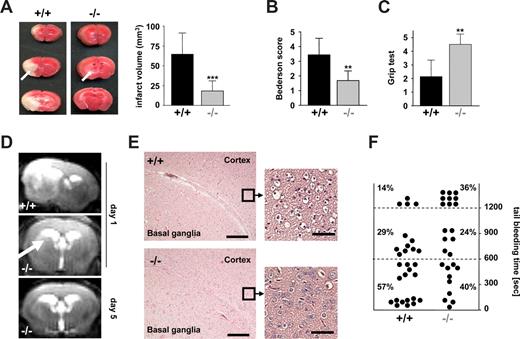

We have recently shown that STIM1 is an essential mediator in the pathogenesis of ischemic brain infarction, indicating that SOCE in platelets is crucial for the stabilization of intravascular thrombi in this setting.11 To directly test this hypothesis, we subjected Orai1−/− chimeras to occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCAO) with a filament as described.24 After 1 hour, the filament was removed to allow reperfusion and the animals were followed for another 24 hours before the extent of infarctions was assessed quantitatively on 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)–stained brain slices. In Orai1−/− chimeras, infarct volumes 24 hours after reperfusion were reduced to less than 30% of the infarct volumes in control chimeras (18.15 ± 12.82 mm3 vs 64.54 ± 26.80 mm3; P < .001) (Figure 4A). The Bederson score assessing global neurologic function (1.69 ± 0.65 vs 3.43 ± 1.13; P < .01) and the grip test, which specifically measures motor function and coordination (4.5 ± 0.76 vs 2.14 ± 1.21; P < .01), revealed that Orai1−/− chimeras developed fewer neurologic deficits compared with controls (Figure 4B,C). Serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on living mice showed that ischemic infarcts on T2-w MRI in Orai1−/− chimeras were markedly reduced compared with control chimeras 24 hours after transient MCAO, thus confirming our histologic findings from TTC-stained brain sections. This protective effect was sustained since no delayed infarct growth was observed between day 1 and day 5. Moreover, a highly sensitive MRI sequence for detection of blood was used to assess hemorrhagic transformation. In contrast to increased bleeding complications in this stroke model after GPIIb/IIIa blockade,24 T2-weighted gradient echo images revealed no hypointensities indicative of intracranial hemorrhages after tMCAO in Orai1−/− chimeras (Figure 4D). This shows that neuroprotection did not occur in expense of bleeding complications despite altered platelet function. Routine histologic assessment of infarcts on hematoxylin and eosin–stained paraffin sections confirmed the TTC and MRI findings. In Orai1−/− chimeras, infarcts were restricted to the basal ganglia, whereas in control animals the neocortex was regularly involved (Figure 4E). In accordance with the findings of the cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model, we found only a minor bleeding tendency of the Orai1−/− chimeras after amputating the tip of their tail (Figure 4F).

Orai1−/− chimeras are protected from cerebral ischemia without displaying major bleeding. (A left panel) Representative images of 3 corresponding coronal sections from control and Orai1−/− chimeras mice stained with TTC 24 hours after tMCAO. Infarct areas are marked with arrows. (Right panel) Brain infarct volumes in control (n = 7) and Orai1−/− chimeras (n = 7); ***P < .001. (B,C) Neurologic Bederson score and grip test assessed at day 1 following tMACO of control (n = 7) and Orai1−/− chimeras (n = 7); **P < .01. Error bars represent plus or minus SD. (D) The coronal T2-w MR brain image shows a large hyperintense ischemic lesion at day 1 after tMCAO in controls (left). Infarcts are smaller in Orai1−/− chimeras (middle, white arrow), and T2 hyperintensity decreases by day 5 during infarct maturation (right). Importantly, hypointense areas indicating intracerebral hemorrhage were not seen in Orai1−/− chimeras, demonstrating that Orai1 deficiency does not increase the risk of hemorrhagic transformation, even at advanced stages of infarct development. (E) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of corresponding territories in the ischemic hemispheres of control and Orai1−/− chimeras. Infarcts are restricted to the basal ganglia in Orai1−/− chimeras but consistently include the cortex in controls. Magnification, 100×-fold and ×400 (10×/0.3 NA and 40×/0.75 NA objectives; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). Bars represent 300 μm (left) and 37.5 μm (right). (F) Bleeding time is only mildly prolonged in Orai1−/− chimeras after amputating the tail tip of anesthetized mice. Each dot represents 1 individual.

Orai1−/− chimeras are protected from cerebral ischemia without displaying major bleeding. (A left panel) Representative images of 3 corresponding coronal sections from control and Orai1−/− chimeras mice stained with TTC 24 hours after tMCAO. Infarct areas are marked with arrows. (Right panel) Brain infarct volumes in control (n = 7) and Orai1−/− chimeras (n = 7); ***P < .001. (B,C) Neurologic Bederson score and grip test assessed at day 1 following tMACO of control (n = 7) and Orai1−/− chimeras (n = 7); **P < .01. Error bars represent plus or minus SD. (D) The coronal T2-w MR brain image shows a large hyperintense ischemic lesion at day 1 after tMCAO in controls (left). Infarcts are smaller in Orai1−/− chimeras (middle, white arrow), and T2 hyperintensity decreases by day 5 during infarct maturation (right). Importantly, hypointense areas indicating intracerebral hemorrhage were not seen in Orai1−/− chimeras, demonstrating that Orai1 deficiency does not increase the risk of hemorrhagic transformation, even at advanced stages of infarct development. (E) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of corresponding territories in the ischemic hemispheres of control and Orai1−/− chimeras. Infarcts are restricted to the basal ganglia in Orai1−/− chimeras but consistently include the cortex in controls. Magnification, 100×-fold and ×400 (10×/0.3 NA and 40×/0.75 NA objectives; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). Bars represent 300 μm (left) and 37.5 μm (right). (F) Bleeding time is only mildly prolonged in Orai1−/− chimeras after amputating the tail tip of anesthetized mice. Each dot represents 1 individual.

Discussion

Our results show that Orai1 is the principal SOC channel in platelets and that its absence leads to a similarly severe defect in SOCE as the absence of STIM1.11 This finding was unanticipated given previous reports that suggested an important role of channels of the TRPC family, most notably TRPC1, in this process.12–14,29 STIM1 has been shown to interact with members of the TRPC family, including TRPC1,30 and to activate them directly and indirectly by the formation of heteromultimers.31 Very recently, however, Jardin et al proposed that the interaction between STIM1 and TRPC1 is mediated by Orai1, which thereby regulates the mode of activation of TRPC1-forming Ca2+ channels.32 Based on this hypothesis, lack of TRPC1 should have a similar effect on SOCE as Orai1 deficiency. This is, however, not the case as revealed by the recent analysis of TRPC1−/− mice, which showed no detectable defect in platelet SOCE and cellular activation in vitro and in vivo.15 In addition, the proposed important role of TRPC1 in SOCE in human platelets has been questioned by others,33 and the extremely low expression levels of the protein in human and mouse platelets15 make even an indirect involvement of TRPC1 in SOCE very unlikely. In line with this assumption, previous studies in different cell systems have shown that STIM1 and Orai1 are sufficient to mediate SOCE,34–36 strongly suggesting that these 2 proteins are the major players in platelet SOCE, although the association of Orai1 with other proteins cannot be excluded.

Lack of Orai1 resulted in strongly reduced but not abolished SOCE, indicating that other channels might mediate this residual Ca2+ influx, possibly Orai2 and/or Orai3, both of which were detected at low amounts in human and mouse platelets at mRNA level (Figure 1). Alternatively, the residual Ca2+ entry could be mediated by store-independent mechanisms as DAG and some of its metabolites can induce non-SOCE37 and TRPC6 could be a channel to mediate this response.33

Orai1 deficiency resulted in severely reduced SOCE in response to TG and all major physiological agonists but in contrast to STIM1 deficiency it had no effect on the filling state of the store. Similar observations have previously been made in Orai1−/− and Stim1−/− mast cells.6,18 This shows that functional SOCE is not a prerequisite of proper store refill and indicates that STIM1 presumably plays a direct, yet unidentified, role in this process. Although the difference in agonist-induced Ca2+ store release between Orai1−/− and Stim1−/− platelets is rather small, it may still be physiologically relevant. This became most evident when FeCl3-induced thrombus formation was assessed in mesenteric vessels (Figure 3). Orai1−/− chimeras were able to form stable thrombi in this model, whereas no occlusive thrombus formation is seen in Stim1−/− chimeras under the same experimental conditions.11 This indicates that the relatively small increase in [Ca2+]i caused by store release in platelets may be sufficient to drive thrombus formation independently of SOCE under certain conditions. As platelets have to respond to vascular injury very rapidly, it appears plausible that the first adhesion and activation is regulated mainly by Ca2+ from the stores and very fast Ca2+ channels such as the ATP-gated P2X1 channel, which has been shown to be critical for proper platelet recruitment and activation at very high shear rates.38 However, SOCE appears to be of pivotal importance for thrombus stabilization on collagen/VWF substrates under conditions of high shear, which is predominantly mediated by the GPIb-GPVI-ITAM axis.1,2 This was also confirmed by the virtually complete protection of Orai1−/− chimeras from tMCAO-induced neuronal damage that was comparable with the protection seen in Stim1−/− chimeras.11 The development of large brain infarcts in this model is known to be highly dependent on functional GPIb and to a somewhat lesser extent also GPVI,24 indicating that STIM1/Orai1-dependent SOCE may indeed occur predominantly downstream of these receptors during intracerebral thrombus formation following transient ischemia. Importantly, this marked protection was not associated with increased occurrence of intracranial bleeding, which is still the major obstacle in current stroke treatment.3 In line with this, we observed only a minor increase in tail bleeding times in Orai1−/− chimeras, suggesting that Orai1, like STIM1, may be of greater relative significance for arterial thrombus formation than for primary hemostasis. Orai1−/− mice also showed unaltered thrombus formation in FeCl3-injured mesenteric arterioles, further supporting the notion that the type and/or severity of injury may determine the relative importance of SOCE for platelet function. One of the possible explanations for this might be the different amounts of thrombin generated under these conditions.39 It has been shown that impaired GPVI/ITAM/PLCγ2 signaling is protective under conditions where low but not high amounts of thrombin are generated,40 but other factors may also be involved.

Taken together, our results establish Orai1 as the long-sought platelet SOC channel that is of central importance for platelet activation during arterial thrombosis and ischemic brain infarction. Since Orai1 is expressed in the plasma membrane, it may be more easily accessible to pharmacological inhibition than STIM1 to prevent or treat ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronmy Rivera Galdos for help with histology.

This work was supported by the Rudolf Virchow Center (Würzburg, Germany) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bonn, Germany; Sonderforschungsbereich 688, A1, B1, and grant Ni556/7-1 to B.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.B., D.V.-S. C.K., M.A. I.P., M. Bender, and M. Bösl performed experiments and analyzed data; and G.S. and B.N. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bernhard Nieswandt, Rudolf Virchow Center, DFG Research Center for Experimental Biomedicine, University of Würzburg, Zinklesweg 10, 97078 Würzburg; e-mail: bernhard.nieswandt@virchow.uni-wuerzburg.de.

References

Author notes

*A.B. and D.V.-S. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 1. Orai1 is the platelet SOC channel. (A) RT-PCR and Western blot analysis of human platelets. Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 were assessed with the primer pairs described in Takahashi et al,22 and Western blot was performed using an antibody from ProSci. (B) Wild-type and Orai1−/− littermates (3 weeks old). (C) Body weights of wild-type (+/+) and Orai1−/− (−/−) mice. Error bars represent plus or minus SD. (D) RT-PCR analyses of platelet and thymocyte mRNA from wild-type (+/+), original Orai1−/− (−/−), and Orai1−/− bone marrow chimera (−/− BMc) mice. Orai1-, Orai2-, and Orai3-specific forward and reverse primers were used22; actin served as control. (E) Fura-2–loaded platelets were stimulated with 5 μM TG for 10 minutes, followed by addition of 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ and monitoring of [Ca2+]i. Representative measurements (left) and maximal Δ[Ca2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group) before and after addition of 1 mM Ca2+ (right) are shown. □ represents Stim1−/− platelets.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/113/9/10.1182_blood-2008-07-171611/6/m_zh80240828380001.jpeg?Expires=1767717965&Signature=DFNPhm07gp3vyEL3DUx4nhzf9hCUwzhty1PAVEEsJk6FA5~PdfvYOg6TCgnkOFrvCc7tOAN7xK-PGDdkx2GWtvSqlwddQvLkz2rvoY-xYxRf83yw4jTVRZQrf28yZuIcRikSjpaYE6LG6QpjHYWAVEsMWo9BlCA9wTJ3TyQK2pHAkvvMAvaMxBs1P1eleoyrpffk-nh~N665Z0wUhwCfFVS49M5pg6ht8wCkZoj3OkndMx-9zvMbmto7SoAjZNStR1BehqnEnWVLpcoNm17O0i9L~ONMf3N8KoQWRzqtSJnXx4aBbj1mXxjL-78AGd1C~jZbXpJZUz30oTKJrkrpIg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. Defective agonist-induced Ca2+ response and aggregate formation under flow in Orai1−/− platelets. Fura-2–loaded wild-type (black line) or Orai1−/− (gray line) platelets were stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), or CRP (10 μg/mL) in calcium-free medium or in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (1 mM), and [Ca2+]i was monitored. Representative measurements (A) and maximal Δ[Ca 2+]i plus or minus SD (n = 4 per group; B) are shown. (C) Impaired aggregation of Orai1−/− platelets (gray lines) in response to collagen, but not ADP and thrombin. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of αIIbβ3 integrin activation (left panel) and degranulation-dependent P-selectin exposure (right panel) in response to thrombin (0.1 U/mL), ADP (10 μM), CRP (10 μg/mL), and CVX (1 μg/mL). Results are means plus or minus SD of 6 mice per group. (E) Orai1−/− platelets in whole blood fail to form stable thrombi when perfused over a collagen-coated (0.2 mg/mL) surface at a shear rate of 1700 s−1. (Top) Representative phase contrast images. (Bottom) Mean surface coverage (left) and relative platelet deposition as measured by the integrated fluorescent intensity (IFI) per square millimeter (right) plus or minus SD (n = 4). Bar represents 30 μm. *P < .05; ***P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/113/9/10.1182_blood-2008-07-171611/6/m_zh80240828380002.jpeg?Expires=1767717965&Signature=TYHPC27KT~acgA0EsG0tBAu2dwyNyFNBytaux8lP4CqZ9Y6NLcxlwKHWZgNAV1ibB6t4cSnqWbliuvAh8nypZ3cgl-qyNgHDUl0ydApJt-3CaBbc7TiLac2mnl1xjHh8vYUaYGaIZjq2yfl8jQQklLoe9IRBkkKdf8Arkl7zw3Pxfhi3qQGPC8KwVa1hLYSBIQShqylv6cJWNTfNLLugSu0q15Vw-ce4BsD1Rd~SH9lF0h3AO491idXQGq2GQxc3o5HeSXhoraFT5ZPru99bdKjRAFTmt0~GXBPfO1lgr30B1Az8ToUjJnEZh-vljFpGUbze2uFnsrDoN18-bcfFqA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal