Treatment failure in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is related to cellular resistance to glucocorticoids (eg, prednisolone). Recently, we demonstrated that genes associated with glucose metabolism are differentially expressed between prednisolone-sensitive and prednisolone-resistant precursor B-lineage leukemic patients. Here, we show that prednisolone resistance is associated with increased glucose consumption and that inhibition of glycolysis sensitizes prednisolone-resistant ALL cell lines to glucocorticoids. Treatment of prednisolone-resistant Jurkat and Molt4 cells with 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), lonidamine (LND), or 3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA) increased the in vitro sensitivity to glucocorticoids, while treatment of the prednisolone-sensitive cell lines Tom-1 and RS4; 11 did not influence drug cytotoxicity. This sensitizing effect of the glycolysis inhibitors in glucocorticoid-resistant ALL cells was not found for other classes of antileukemic drugs (ie, vincristine and daunorubicin). Moreover, down-regulation of the expression of GAPDH by RNA interference also sensitized to prednisolone, comparable with treatment with glycolytic inhibitors. Importantly, the ability of 2-DG to reverse glucocorticoid resistance was not limited to cell lines, but was also observed in isolated primary ALL cells from patients. Together, these findings indicate the importance of the glycolytic pathway in glucocorticoid resistance in ALL and suggest that targeting glycolysis is a viable strategy for modulating prednisolone resistance in ALL.

Introduction

Treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) includes the use of several classes of chemotherapeutic agents, including glucocorticoids (GCs), Vinca alkaloids, and anthracyclines. The glucocorticoids prednisolone and dexamethasone play an essential role in essentially all therapy protocols, due to their ability to block cell-cycle progression and induce apoptosis in ALL cells.1,–3 Although treatment of childhood ALL has greatly improved over the past decades, conventional combination chemotherapy still fails in approximately 20% of the patients.4 Most therapeutic failures can be explained by cellular resistance to antileukemic drugs.5 Resistance to prednisolone at initial diagnosis in particular is related to an unfavorable event-free survival. In addition, in vitro prednisolone resistance is recognized as an important negative parameter for long-term clinical outcome, even in patients who initially have a good in vivo response to glucocorticoids.6,–8 Therefore, it is important to find alternative therapies that can reverse resistance toward prednisolone and dexamethasone

Previous experiments performed in our laboratories showed that prednisolone resistance in precursor B-ALL patients is associated with an increased expression of genes involved in glucose metabolism, suggesting that glucocorticoid resistance may be linked with an increased rate of glycolysis.9 Glycolysis is a series of metabolic reactions by which 1 molecule of glucose is converted to 2 molecules of pyruvate with a net gain of energy in the form of 2 molecules of ATP.10 Each reaction in the glycolytic pathway is catalyzed by a specific enzyme, such as hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase (PFK), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and enolase. Under aerobic conditions, pyruvate can be further oxidized in the mitochondria to CO2 and H2O through oxidative phosphorylation, yielding 36 ATP molecules per mol-ecule glucose; in the absence of oxygen, glycolysis prevails. Cancer cells also shift their metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation toward the less efficient glycolysis, independent of the presence of oxygen.11 Here, we show that an increased glycolytic rate in ALL cells is directly related to glucocorticoid resistance and that inhibition of glycolysis, either by the use of synthetic compounds or by use of RNA interference, renders otherwise resistant leukemic cells susceptible to prednisolone. Importantly, reversal of prednisolone resistance was not limited to established cell lines, but was also observed in primary leukemic cells of pediatric ALL patients. These data suggest that targeting the glycolytic pathway may be a valuable strategy to modulate glucocorticoid resistance in the treatment of pediatric ALL.

Methods

Cell culture and lentiviral infections

Human 293T cells and Jurkat, Molt4, Tom-1, RS4;11 leukemia cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a 5% humidified atmosphere in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; 293T) or RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.125 μg/mL fungizone (PSF; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Pools of early passage Jurkat shGAPDH cells were generated by infection with lentiviral pLKO.1 Mission shRNA vectors (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) using Retronectin (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and selected in 1 μg/mL puromycin.

Patient samples

Within 24 hours after sampling, mononuclear cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood samples from untreated children at initial diagnosis of ALL were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (density 1.077 g/mL; Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway), centrifuged at 480g for 15 minutes at room temperature. Isolated mononuclear cells were washed twice and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Dutch modification without l-glutamine; Invitrogen), 5 μg/mL insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 5 ng/mL sodium selenite (ITS media supplement; Sigma-Aldrich), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.125 μg/mL amphotericin B, 0.2 mg/mL gentamicin, and 20% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). Contaminating nonleukemic cells were removed using immunomagnetic beads as described earlier.12 Bone marrow and peripheral blood samples were collected from children with newly diagnosed ALL as approved by the institutional review board of Erasmus MC and after written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

In vitro MTT drug resistance assay

Responsiveness of leukemia cells to prednisolone (PRED; Bufa Pharmaceutical Products, Uitgeest, The Netherlands), vincristine (VCR; TEVA Pharma, Utrecht, The Netherlands), dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DEX; Brocacef, Maarssen, The Netherlands), L-asparaginase (ASP; Paronal, Christiaens, The Netherlands), and daunorubicin (DNR; Cerubidine; Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) was determined by the 4-day in vitro 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) drug resistance assay.13 The drug concentration lethal to 50% of the ALL cells (LC50) was used as a measure of cellular drug resistance. The final drug concentrations ranged from 24 to 15 000 μg/mL prednisolone and 1.5 to 800 μg/mL dexamethasone for the prednisolone-resistant cell lines (Jurkat and Molt4) and from 0.008 to 250 μg/mL prednisolone and 10−5 to 10−2 μg/mL dexamethasone for the prednisolone-sensitive cell lines (Tom-1 and RS4;11) and patient cells. Different concentrations were used due to differences in glucocorticoid resistance, but correspond with the induction of similar amounts of cell death. For RS4;11 and Tom-1 cell lines the amount of prednisolone used corresponds with the LC50 of in vitro good responding patients, while the amount used for Jurkat and Molt4 corresponds with poor responders.8 The concentrations of L-asparaginase, vincristine, and daunorubicin were the same for all cell lines (0.003-10 IU/mL ASP, 0.0005-50 μg/mL VCR, and 0.002-2 μg/mL DNR, respectively). Inhibition of glycolysis was established by addition of 0.25 to 2 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), 62.5 μM lonidamine (LND), or 30 μM 3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA; Sigma-Aldrich). The metabolic MTT assay revealed similar results as a trypan blue exclusion assay, which is based on cell counting (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Calculation of synergy

A possible synergistic effect was tested according to the criteria described by Berenbaum in 1977.14 Briefly, a dose-response curve was constructed for each single drug and for combinations of 2 drugs together. Equipotent drug concentrations were then applied to the equation used by Berenbaum as follows: [Drug Ain combination with B] / [Drug Aalone] + [Drug Bin combination with A]/[Drug Balone]. The value calculated from this formula is referred to as the synergy factor (Fsyn), and a value less than 1 indicates synergy, Fsyn equal to 1 indicates an additive effect, and Fsyn greater than 1 an antagonistic effect (negative synergy).

Glucose consumption assay

Glucose consumption was measured as the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate and NADH with the Glucose (HK) Assay Kit, as described by the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, 106 leukemic cells were grown in RPMI containing 2 g/L glucose. After 4 days, the medium was collected by centrifugation to remove the cells, and incubated for 2 hours with glucose assay buffer, containing 1.5 mM NAD, 1 mM ATP, 1 U/mL hexokinase, and 1 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. During this time, glucose is phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate. Glucose-6-phosphate is then oxidized to 6-phospho-gluconate in the presence of oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), reducing NAD to an equimolar amount of NADH. The conversion of NAD to NADH can be measured by the increase in absorbance at 340 nm, which is directly proportional to the glucose concentration.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from a minimum of 5 × 106 leukemic cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) or the QIAGEN RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Quantification of RNA was performed using a spectrophotometer, and cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II, 1 μg total mRNA template and random hexamers as primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis was performed on the Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Foster City, CA) by monitoring the increase of fluorescence by degradation of a Taqman probe from double-stranded DNA. PCR primers were designed with Oligo 6.22 software (Molecular Biology Insights, Cascade, CO) and spanned exon junctions to prevent the amplification of any possible contaminating genomic DNA. Ribosomal protein S20 (RPS20) was used as a control gene for normalization. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Results

Several genes involved in glucose metabolism were previously identified in our laboratory as being differentially expressed in pediatric precursor B-ALL in relation to glucocorticoid resistance.9 Microarray gene expression profiling experiments showed that expression levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3/SLC2A3), carbonic anhydrase 4 (CA4), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were significantly higher (P < .001) in prednisolone-resistant precursor B-ALL cells compared with prednisolone-sensitive ALL cells. To further investigate whether the glycolysis pathway is associated with glucocorticoid resistance in ALL, several experiments were carried out.

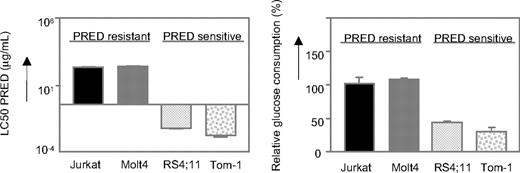

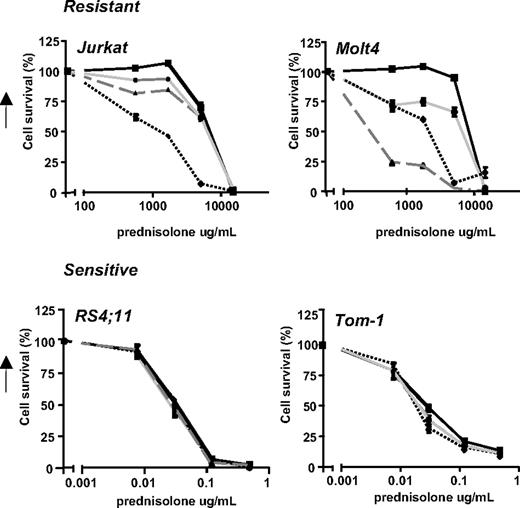

First, the glucose uptake of various prednisolone-resistant and prednisolone-sensitive leukemic cell lines was determined. As shown in Figure 1, the prednisolone-resistant cell lines Jurkat and Molt4 (LC50 ≥ 250 μg/mL) show high glucose consumption compared with the prednisolone-sensitive cell lines Tom-1 and RS4;11, concordant with the microarray data.

Glycolysis is up-regulated in prednisolone-resistant human leukemia cells. Graphic representation of in vitro prednisolone responsiveness (left panel) and glucose consumption (right panel) of 2 prednisolone-resistant and 2 prednisolone-sensitive human ALL cell lines. Response to prednisolone was measured by the MTT assay; glucose consumption was calculated per cell by measuring the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate. The glucose consumption in Jurkat cells after 4 days of incubation was set to be 100%, corresponding to approximately 75% of the total glucose present in the medium (1.5 g/L). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Glycolysis is up-regulated in prednisolone-resistant human leukemia cells. Graphic representation of in vitro prednisolone responsiveness (left panel) and glucose consumption (right panel) of 2 prednisolone-resistant and 2 prednisolone-sensitive human ALL cell lines. Response to prednisolone was measured by the MTT assay; glucose consumption was calculated per cell by measuring the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate. The glucose consumption in Jurkat cells after 4 days of incubation was set to be 100%, corresponding to approximately 75% of the total glucose present in the medium (1.5 g/L). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

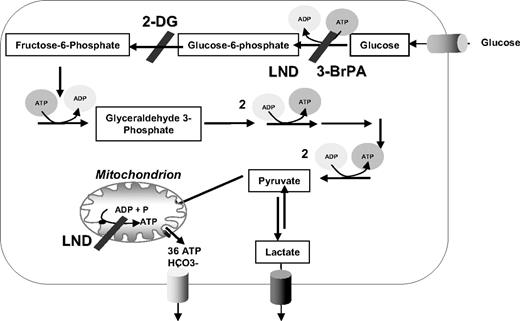

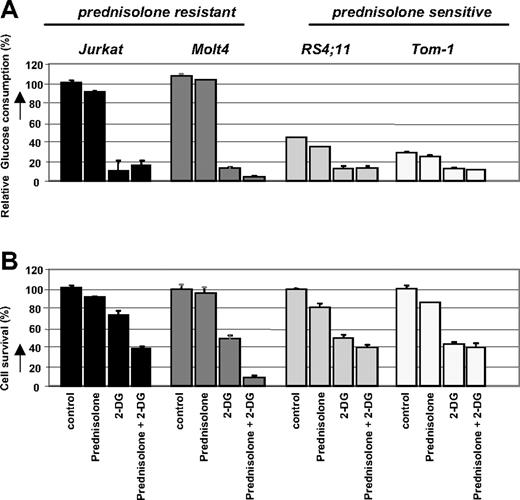

Next, we investigated the response of these leukemic cell lines to prednisolone while inhibiting the glycolysis pathway. Cells were incubated with the glucose analog 2-DG, which competes with glucose for transmembrane transport and is phosphorylated by hexokinase to 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate. After phosphorylation, 2-DG cannot be metabolized further, leading to a proximal blockade of glycolysis15 (Figure 2). Treatment of the cell lines Jurkat, Molt4, RS4;11, and Tom-1 with sublethal concentrations of 2-DG, either alone or in combination with prednisolone, resulted in a considerable reduction of glucose uptake compared with nontreated cells (Figure 3A). This decrease in glucose consumption was not seen when cells were incubated with prednisolone alone. Interestingly, the combination of 2-DG and prednisolone resulted in markedly increased cell death in the prednisolone-resistant cell lines Jurkat and Molt4, compared with treatment with 2-DG or prednisolone as single drugs (Figure 3B). This synergistic effect (Fsyn = 0.61 ± 0.05 and 0.39 ± 0.25 for Jurkat and Molt4, respectively) on cell death was not observed in the prednisolone-sensitive cell lines RS4;11 and Tom-1 (Fsyn = 0.98 ± 0.03 and 1.05 ± 0.04, respectively).

Schematic representation of glucose metabolism in mammalian cells. Glycolytic inhibitors used in this study are indicated as 2-DG, 3-BrPA, and LND.

Schematic representation of glucose metabolism in mammalian cells. Glycolytic inhibitors used in this study are indicated as 2-DG, 3-BrPA, and LND.

Effect of 2-DG treatment on glucose consumption and prednisolone- induced cytotoxicity in human ALL cell lines. Graphic representation of relative glucose consumption (A) or in vitro prednisolone responsiveness (B) in 2 prednisolone-resistant and 2 prednisolone-sensitive ALL cell lines after 2-DG treatment. Glucose consumption was calculated by measuring the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate, and glucose consumption in Jurkat cells was set at 100%. Response to prednisolone was measured by the MTT assay; cell survival in nontreated cells was set at 100%. Used concentrations of prednisolone and 2-DG varied depending on cellular toxicity (550 μg/mL and 0.078 μg/mL prednisolone, and 2 mM and 0.5 mM for -resistant and -sensitive cell lines, respectively). Representative experiments are shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Effect of 2-DG treatment on glucose consumption and prednisolone- induced cytotoxicity in human ALL cell lines. Graphic representation of relative glucose consumption (A) or in vitro prednisolone responsiveness (B) in 2 prednisolone-resistant and 2 prednisolone-sensitive ALL cell lines after 2-DG treatment. Glucose consumption was calculated by measuring the conversion of glucose to 6-phosphogluconate, and glucose consumption in Jurkat cells was set at 100%. Response to prednisolone was measured by the MTT assay; cell survival in nontreated cells was set at 100%. Used concentrations of prednisolone and 2-DG varied depending on cellular toxicity (550 μg/mL and 0.078 μg/mL prednisolone, and 2 mM and 0.5 mM for -resistant and -sensitive cell lines, respectively). Representative experiments are shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

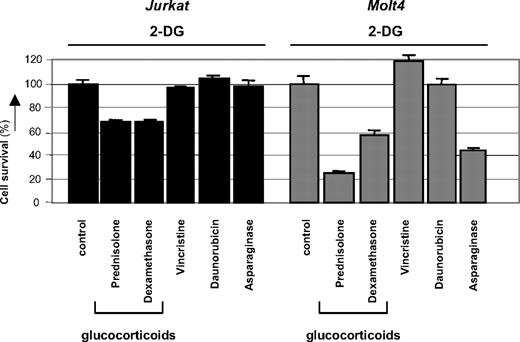

2-DG acts in synergy with glucocorticoids but not with vincristine or daunorubicin

2-DG has recently been reported to cooperate with nonglucocorticoid drugs in inducing cell death of several types of carcinoma cells.16,–18 To test if the observed synergism of 2-DG with prednisolone in leukemic cells was specific for glucocorticoids, 2-DG was coincubated with sublethal concentrations of the prednisolone-analog dexamethasone or with other cytostatics that are frequently used in the treatment of leukemia, that is, vincristine, daunorubicin, and asparaginase. As shown in Figure 4, the antimitotic agent vincristine or the topoisomerase II inhibitor daunorubicin did not synergize with 2-DG in the leukemic cell lines Jurkat and Molt4; no difference was observed in the amount of cell death between a combination of 2-DG and these agents or treatment with 2-DG alone. Addition of L-asparaginase in combination with 2-DG, on the other hand, increased cytotoxicity in Molt4 cells (Fsyn = 0.67 ± 0.07), but this synergism was not observed in Jurkat cells. Incubation of 2-DG in combination with the glucocorticoids prednisolone or dexamethasone, however, markedly affected cell survival in both cell lines tested, indicating that 2-DG consistently alters glucocorticoid resistance in these cell lines.

Modulation of drug-resistance by 2-DG. Graphic representation of in vitro responsiveness to cytotoxic drugs in 2 prednisolone-resistant ALL cell lines after 2-DG treatment, as assessed by the MTT assay. Concentrations used were 1 mM (Molt4) or 2 mM 2-DG (Jurkat), 550 μg/mL prednisolone, 100 μg/mL dexamethasone, 0.5 ng/mL vincristine, and 0.0098 U/mL L-asparaginase. Cell survival in cells treated only with 2-DG was set at 100% to visualize the effect of synergy. Representative experiments are shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Modulation of drug-resistance by 2-DG. Graphic representation of in vitro responsiveness to cytotoxic drugs in 2 prednisolone-resistant ALL cell lines after 2-DG treatment, as assessed by the MTT assay. Concentrations used were 1 mM (Molt4) or 2 mM 2-DG (Jurkat), 550 μg/mL prednisolone, 100 μg/mL dexamethasone, 0.5 ng/mL vincristine, and 0.0098 U/mL L-asparaginase. Cell survival in cells treated only with 2-DG was set at 100% to visualize the effect of synergy. Representative experiments are shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Inhibition of the glycolytic pathway increases prednisolone-induced toxicity

Although the use of 2-DG as an inhibitor of glycolysis is widely recognized, 2-DG can modulate other cellular processes as well, such as protein glycosylation or the so-called unfolded protein response (UPR) in the endoplasmic reticulum.19 Therefore, 2 other compounds that inhibit glucose metabolism were tested for their effect on prednisolone sensitivity in leukemic cell lines. Addition of 30 μM 3-BrPA20 or 62.5 μM LND,21 that affect both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 2) also modulated prednisolone resistance in Jurkat and Molt4 cells, but did not affect prednisolone sensitivity in RS4;11 and Tom-1 cells, analogous to the results of 2-DG treatment (Figure 5).

Effect of glycolytic inhibitors on prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity in prednisolone–resistant and prednisolone-sensitive cell lines. Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness, as assessed by the MTT assay in 2 prednisolone-resistant (top panel) and 2 prednisolone-sensitive ALL cell lines (bottom panel) after treatment with glycolytic inhibitors. Cells were treated with 1 mM (Jurkat, Molt4) or 0.5 mM 2-DG (▲), 62.5 μM LND ( ), 30 μM 3-BrPA (●) in combination with prednisolone, as indicated in the figure. Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). To visualize synergy, the survival rate of prednisolone in combination with an inhibitor was corrected for the toxicity caused by the inhibitor itself (set to 100%). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

), 30 μM 3-BrPA (●) in combination with prednisolone, as indicated in the figure. Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). To visualize synergy, the survival rate of prednisolone in combination with an inhibitor was corrected for the toxicity caused by the inhibitor itself (set to 100%). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Effect of glycolytic inhibitors on prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity in prednisolone–resistant and prednisolone-sensitive cell lines. Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness, as assessed by the MTT assay in 2 prednisolone-resistant (top panel) and 2 prednisolone-sensitive ALL cell lines (bottom panel) after treatment with glycolytic inhibitors. Cells were treated with 1 mM (Jurkat, Molt4) or 0.5 mM 2-DG (▲), 62.5 μM LND ( ), 30 μM 3-BrPA (●) in combination with prednisolone, as indicated in the figure. Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). To visualize synergy, the survival rate of prednisolone in combination with an inhibitor was corrected for the toxicity caused by the inhibitor itself (set to 100%). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

), 30 μM 3-BrPA (●) in combination with prednisolone, as indicated in the figure. Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). To visualize synergy, the survival rate of prednisolone in combination with an inhibitor was corrected for the toxicity caused by the inhibitor itself (set to 100%). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

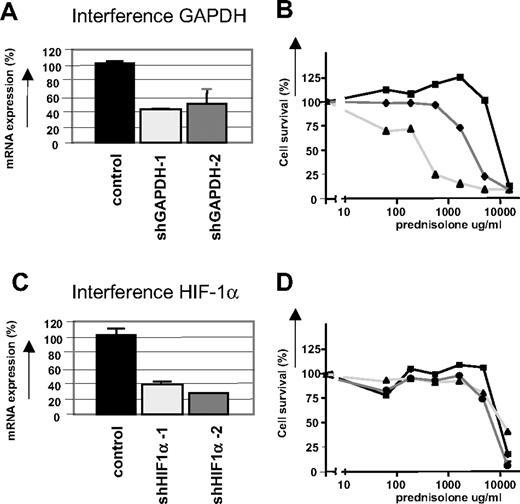

To demonstrate further that the glycolytic pathway is associated with prednisolone resistance in ALL cells, Jurkat cells were infected with lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids to stably silence GAPDH gene expression.22 The efficiency of RNA interference was monitored at the RNA level by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), because GAPDH is a very abundant protein and differences in expression are difficult to detect on Western blot. As shown in Figure 6A, RNA interference with 2 different shRNA sequences targeting GAPDH resulted in a reduction in gene expression of approximately 60%, and increased prednisolone sensitivity, confirming the link between glycolysis and glucocorticoid resistance (Figure 6B). RNA interference for another gene that was differentially regulated in the microarray experiments, HIF-1α, did not affect prednisolone sensitivity in Jurkat cells (Figure 6C,D), suggesting that the up-regulation of HIF-1α is not causally related to glucocorticoid resistance in ALL.

Inhibition of GAPDH expression by RNA interference increases prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity. (A) mRNA levels of GAPDH in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting GAPDH were used (shGAPDH-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100% and relative expression levels were calculated. (B) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for GAPDH ( , ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). (C) mRNA levels of HIF-1α in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting HIF-1α were used (sh HIF-1α-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100%, and relative expression levels were calculated. (D) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for HIF-1α (

, ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). (C) mRNA levels of HIF-1α in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting HIF-1α were used (sh HIF-1α-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100%, and relative expression levels were calculated. (D) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for HIF-1α ( , ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

, ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Inhibition of GAPDH expression by RNA interference increases prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity. (A) mRNA levels of GAPDH in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting GAPDH were used (shGAPDH-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100% and relative expression levels were calculated. (B) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for GAPDH ( , ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). (C) mRNA levels of HIF-1α in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting HIF-1α were used (sh HIF-1α-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100%, and relative expression levels were calculated. (D) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for HIF-1α (

, ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). (C) mRNA levels of HIF-1α in Jurkat cells as measured by qPCR. Two different shRNA sequences targeting HIF-1α were used (sh HIF-1α-1 and -2). Expression of cells infected with nonsilencing shRNA sequences was set at 100%, and relative expression levels were calculated. (D) Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness after RNA interference in cells interfered for HIF-1α ( , ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

, ▲) or in cells infected with a nonsilencing shRNA sequence (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

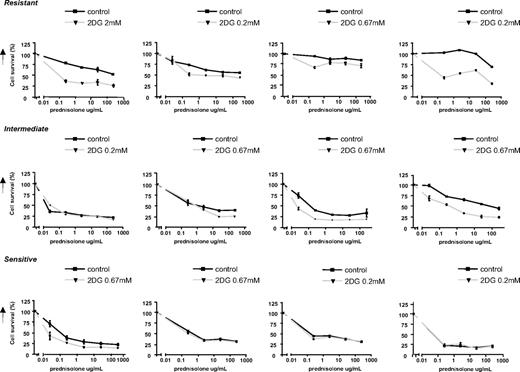

2-DG increases prednisolone-induced toxicity in ALL patient cells

The results described above clearly show that inhibition of glycolytic metabolism increases prednisolone sensitivity in ALL cell lines. To evaluate further the importance of this finding for treatment of ALL patients, in vitro studies were performed on primary leukemia cells isolated from bone marrow of patients with newly diagnosed ALL, using the MTT assay. The effect of 2-DG on prednisolone-induced toxicity was tested on leukemic cells of ALL patient samples that were identified as prednisolone-resistant (LC50 ≥ 150, n = 4), as intermediately resistant (LC50 = 0.1-150, n = 4) or sensitive to prednisolone (LC50 ≤ 0.1, n = 4). In concordance with the cell line results, a synergistic effect was observed between 2-DG and prednisolone in ALL cells from resistant patients (Fsyn < 0.5) and in some of the intermediately resistant cells, but not in patients whose ALL cells were sensitive to prednisolone (Figure 7).

Effect of 2-DG treatment on prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity in primary ALL cells. Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness, in prednisolone-resistant ALL patients (top panel), -intermediate patients (middle panel), and -sensitive patients (bottom panel) as assessed by the MTT assay. Concentrations 2-DG varied from 0.2 mM to 2 mM (▼), depending on the patient sample sensitivity. To visualize the synergy, the survival of cells treated with prednisolone and 2-DG was corrected for the toxic effect of 2-DG given as single drug (set at 100%). Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Effect of 2-DG treatment on prednisolone-induced cytotoxicity in primary ALL cells. Cell survival curves representing in vitro prednisolone responsiveness, in prednisolone-resistant ALL patients (top panel), -intermediate patients (middle panel), and -sensitive patients (bottom panel) as assessed by the MTT assay. Concentrations 2-DG varied from 0.2 mM to 2 mM (▼), depending on the patient sample sensitivity. To visualize the synergy, the survival of cells treated with prednisolone and 2-DG was corrected for the toxic effect of 2-DG given as single drug (set at 100%). Cells treated only with prednisolone served as controls (■). A representative experiment is shown; data are presented as means plus or minus SD (n = 3).

Discussion

Resistance to glucocorticoids is a well recognized feature of poor prognosis in the treatment of childhood ALL. Considering the poor prognosis of glucocorticoid resistance and the importance of prednisolone and dexamethasone in contemporary ALL treatment protocols, the development of strategies to reverse resistance to these agents could have a profound impact on ALL treatment efficacy. Several potential mechanisms for prednisolone resistance have been studied in leukemic cell lines and ALL patients, but most of them did not reveal clues for causes of resistance. Although the P-glycolprotein pump (P-gp) plays a role in glucocorticoid transport, we have shown previously that the efflux of glucocorticoids by P-gp is not a significant contributor to glucocorticoid resistance in leukemic blasts.23 In addition, the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is not related to glucocorticoid resistance in childhood ALL, and mutations in the GR are rare.24,25 Furthermore, reduced affinity of GR for its ligand, defective translocation of GR across the nuclear membrane, and binding of GR to the glucocorticoid-responsive element are also not thought to be of major importance in glucocorticoid resiststance in leukemia (reviewed by Tissing et al1 and Haarman et al26 ). Here we show that leukemic cells that are resistant to glucocorticoid treatment in vitro have increased glucose consumption compared with sensitive cells, and that down-regulation of glycolysis can attenuate glucocorticoid resistance in pediatric ALL.

It has been shown before that cancer cells, including leukemic cells, shift their energy production from oxidative phosphorylation toward the less efficient glycolysis pathway and catabolize glucose at a higher rate than their nontransformed counterparts—the so-called Warburg effect.27,28 This increased glycolysis rate is due to an up-regulation of several genes involved in glycolysis or glucose uptake.28,29 We observed a similarly higher expression of glycolysis-related genes in glucocorticoid-resistant ALL cells in our previous analysis of gene expression in primary ALL cells.9 This up-regulation in gene expression is generally believed to be due to activation of the transcription factors c-MYC30 or HIF-1α.31,32 HIF-1α has been shown to stimulate glucose consumption when cells are deprived of oxygen (hypoxia) and to directly regulate the expression of genes involved in glycolysis, including glycolytic enzymes33,–35 and membrane glucose transporters.36 However, HIF activity can also be stabilized in the presence of oxygen, by growth factors and signal transduction routes that also participate in carcinogenesis, including the Ras pathway.37 Interestingly, HIF-1–dependent transactivation can be stimulated by glucocorticoids via the glucocorticoid receptor,38 providing a direct link between glycolysis and glucocorticoids. Because HIF-1α was one of the genes with an increased expression in prednisolone-resistant ALL cells in our microarray data, it was tempting to suggest a role for HIF-1α in the up-regulation of glycolysis genes observed in our experiments. However, inhibition of HIF-1α by RNA interference showed no alteration in the sensitivity for prednisolone in Jurkat or Molt4 cell lines in vitro. This indicates that prednisolone resistance in pediatric precursor B-ALL patients is not due to up-regulation of HIF-1α at the transcriptional level.

Another key factor that is thought to be involved in the regulation of glycolysis is the serine/threonine kinase PKB/Akt.39 Akt has been implicated in the regulation of glucose uptake40 and has been shown to induce the expression of the glucose transporters GLUT-1 and GLUT-3.41,–43 Moreover, activation of Akt has been shown to specifically activate glycolysis without affecting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.44 Akt functions through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and the phosphorylation events of Akt and mTOR are thought to be rate-limiting steps in glycolysis.45,–47 Interestingly, inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin decreased prednisolone resistance in ALL cell lines,48 suggesting the involvement of the Akt/mTOR pathway in glucocorticoid resistance in pediatric ALL. A role for Akt in glucocorticoid resistance is even more plausible if one thinks about its function in cell survival. Akt has been shown to promote mitochondrial integrity and inhibit cytochrome c release, thereby preventing apoptosis.49 Importantly, Akt requires the presence of glucose to exert its antiapoptotic function,50 stressing once more the importance of the glycolysis pathway as a target for cancer treatment.

Given that cancer cells have higher glycolytic rates than their nontransformed counterparts, inhibition of glycolysis more specifically affects tumor cells and has little or no effect on normal cells.51 Inhibition of glycolysis by 2-DG but not inhibition of the oxidative phosphorylation process was shown to reduce the viability of the PER-427 T-ALL cell line, pointing to glycolysis as potential therapeutic target.28 Here, we show that disruption of the glycolytic pathway specifically affects prednisolone-resistant leukemia cells with high metabolic activity, while no sensitizing effect is observed in cells already sensitive to prednisolone. This synergistic effect is independent of the glycolytic inhibitor used: addition of 2-DG, 3-BrPA, or LND all rendered otherwise resistant leukemia cells more susceptible to prednisolone. Moreover, down-regulation of GAPDH by use of RNA interference also modulated prednisolone sensitivity, confirming a direct link between glucocorticoid resistance and glucose metabolism. Because the sensitizing effect of glycolytic inhibitors on prednisolone resistance was not only observed in ALL cell lines but also in primary cells of pediatric ALL patients, interference with the glycolysis pathway seems a promising way to reverse glucocorticoid resistance in childhood leukemia.

In past years, targeting glycolysis has become increasingly more attractive as a therapeutic approach for several kinds of tumors.52,53 However, short-term inhibition of glycolysis alone appears not to be sufficient to produce significant antitumor effects in vivo. Some of the compounds that are used to block glucose metabolism, such as 3-BrPA, are relatively unstable and show significant inhibition of glycolysis only at relatively high concentrations.54 Similarly, the dose of LND necessary to achieve clinical efficacy is associated with toxicity, limiting the use of these compounds as primary therapy.51 Instead, the use of glycolysis inhibitors in combination with other agents appears to be a more promising approach. Glycolytic inhibitors have been reported to increase the cytotoxicity of other agents, possibly by reducing the cell's ability to repair damage caused by those agents or by increasing the permeability of tumor cells. Addition of LND, for example, has been shown to result in a significant increase in the intracellular concentrations of doxorubicin.55 Moreover, LND has been shown to increase the efficacy of cisplatin, doxorubicin, and melphalan both in vitro and in vivo.56,57 Similarly, the addition of 3-BrPA was found to increase the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin, vincristine, and Ara-C in HL-60/AR cells,54 and the concurrent administration of 2-DG increased the in vivo efficacy of both doxorubicin and paclitaxel in osteosarcoma and non–small cell lung cancer xenografts.51 In our experiments the coincubation of 2-DG did not increase the cytotoxicity of vincristine or daunorubicin in leukemia cells, while it sensitized toward both prednisolone and dexamethasone, suggesting that 2-DG particularly interferes with glucocorticoid action in ALL. Recently, clinical trials have been performed using glycolytic inhibitors in breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, and malignant glioma,52,58,59 and a phase 1/2 trial is currently ongoing for prostate cancer, administering 30 mg/kg (∼0.2 mM) 2-DG on a daily schedule for 2 weeks60 (www.clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT00633087). Moreover, clinical evaluation in brain tumor patients showed that 2-DG is safe to use at doses up to 250 mg/kg body weight (∼1.5 mM) given weekly for 7 weeks.61 This implies that the concentrations of 2-DG used in our in vitro experiments are also applicable in clinical practice. Together, the results presented here point to the importance of the glycolytic pathway in glucocorticoid resistance and suggest that targeting this pathway may be a particularly promising approach to reverse prednisolone resistance in pediatric ALL in patients for whom currently alternative treatment protocols are less successful, for example, patients suffering from a second or later relapse.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Pediatric Oncology Foundation Rotterdam and the Dutch Cancer Society (grants EMCR 2005-3662 and EMCR 2005-3313).

Authorship

Contribution: E.H. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; K.M.K., A.H., and M.J.C.B. performed research; D.J.V., C.M.R., W.E.E., and R.P. discussed data and revised the manuscript; and M.D.B. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: M. L. den Boer, Erasmus MC–Sophia Children's Hospital, Department of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, Dr Molewaterplein 60, 3015 GJ Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: m.l.denboer@erasmusmc.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal