Abstract

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is mediated by platelet autoantibodies that accelerate platelet destruction and inhibit their production. Most cases are considered idiopathic, whereas others are secondary to coexisting conditions. Insights from secondary forms suggest that the proclivity to develop platelet-reactive antibodies arises through diverse mechanisms. Variability in natural history and response to therapy suggests that primary ITP is also heterogeneous. Certain cases may be secondary to persistent, sometimes inapparent, infections, accompanied by coexisting antibodies that influence outcome. Alternatively, underlying immune deficiencies may emerge. In addition, environmental and genetic factors may impact platelet turnover, propensity to bleed, and response to ITP-directed therapy. We review the pathophysiology of several common secondary forms of ITP. We suggest that primary ITP is also best thought of as an autoimmune syndrome. Better understanding of pathogenesis and tolerance checkpoint defects leading to autoantibody formation may facilitate patient-specific approaches to diagnosis and management.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenia is mediated by platelet antibodies that accelerate platelet destruction and inhibit their production. The dominant clinical manifestation is bleeding, which correlates generally with severity of the thrombocytopenia. Most cases are considered primary (hereafter designated ITP), whereas others are attributed to coexisting conditions (secondary ITP; Figure 1).

Estimated fraction of the various forms of secondary ITP based on clinical experience of the authors. The incidence of HP ranges from approximately 1% in the United States to 60% in Italy and Japan. The incidence of HIV and hepatitis C approximates 20% in some populations. Miscellaneous causes of immune thrombocytopenia, for example, posttransfusion purpura, myelodysplasia, drugs that lead to the production of autoantibodies, and other conditions, are not discussed further in this review. ALPS indicates autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; posttx, post–bone marrow or solid organ transplantation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CVID, common variable immune deficiency. In the absence of a systematic analysis of the incidence of secondary ITP, the data shown represent our combined assessment based on experience and reading of the literature. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Estimated fraction of the various forms of secondary ITP based on clinical experience of the authors. The incidence of HP ranges from approximately 1% in the United States to 60% in Italy and Japan. The incidence of HIV and hepatitis C approximates 20% in some populations. Miscellaneous causes of immune thrombocytopenia, for example, posttransfusion purpura, myelodysplasia, drugs that lead to the production of autoantibodies, and other conditions, are not discussed further in this review. ALPS indicates autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; posttx, post–bone marrow or solid organ transplantation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CVID, common variable immune deficiency. In the absence of a systematic analysis of the incidence of secondary ITP, the data shown represent our combined assessment based on experience and reading of the literature. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

This categorization implies that ITP is a single clinical-pathologic entity. However, variability in natural history and response to therapy suggests that ITP comprises heterogeneous disorders that eventuate in the production of platelet autoantibodies. Certain cases of otherwise “typical ITP” are secondary to persistent, often inapparent infections (eg, Helicobacter pylori [HP] or hepatitis C) or are accompanied by coexisting antibodies that might influence outcome (eg, antiphospholipid antibodies). Insights from secondary forms (eg, coexisting immune deficiency and molecular mimicry after infection) suggest that platelet-reactive antibodies arise through diverse mechanisms. In addition, environmental and genetic factors may impact platelet turnover, propensity to bleed, and response to ITP-directed therapy.

Here, we present an overview of the heterogeneity of ITP beginning with diverse immunologic perturbations that might contribute to autoantibody production. We then review the pathophysiology and clinical picture of several secondary forms, placing each into an immunologic context. Finally, we suggest that primary and secondary ITP are best thought of as autoimmune syndromes and that better understanding of their pathogenesis and tolerance checkpoint defects may facilitate disease-specific approaches to diagnosis and management. A text containing a more comprehensive list of references is available in the online data supplement (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Diversity of autoimmune mechanisms

Antibodies, B cells, and T cells

Autoantibodies against platelet antigens are considered the diagnostic hallmark of ITP. In some patients, antibodies recognize antigens derived from a single glycoprotein; whereas in others, antibodies recognize multiple glycoproteins.1 Opsonization by antibody accelerates platelet clearance but can also alter platelet function and interfere with platelet production. Curiously, platelet antibodies are only detected in approximately 60% of patients.2 Failure to detect antibodies might reflect limited test sensitivity, undetected antigens, or additional mechanisms of platelet loss. Potential mechanisms that do not implicate B cells must be reconciled with the more than 80% initial response rate to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and splenectomy.

T cells are also implicated in antibody production and thrombocytopenia. Antibodies are usually isotype-switched and harbor somatic mutations, consistent with a T cell–dependent response.3 The cytokine profile is reported to be consistent with CD4+ Th0/Th1 activation, including increased prevalence of the tumor necrosis factor-α (+252) G/G phenotype.4 In one study, the Th1/Th2 cytokine mRNA ratio correlated inversely with the platelet count,5 although the study was neither prospective nor restricted to untreated patients at presentation. T-cell subset polarization has been attributed to reduced peripheral Th2 cells and Tc2 cells6 or number or function7 of CD25brightFoxp3+ T-regulatory cells. Decreased Fas expression on Th1 and Th2 cells, increased expression of Bcl-2 mRNA, and reduced Bax mRNA on CD4 cells5,8 may each contribute to a breakdown in T-cell tolerance. Moreover, transforming growth factor-β expression (which is associated with an immunosuppressive Th3 profile) correlates with disease activity.9

Tolerance checkpoint defects in immune thrombocytopenia

The lymphocyte repertoire is monitored and purged of autoreactive specificities that arise at different stages of development. The repertoire is also influenced by homeostatic mechanisms that control peripheral compartment size and subset distribution, for example, by the cytokine B-cell activating factor BAFF (BLyS). Increased prevalence of the (−871) TT genotype of the BAFF promoter, accompanied by increased serum BAFF, has been reported in ITP.10

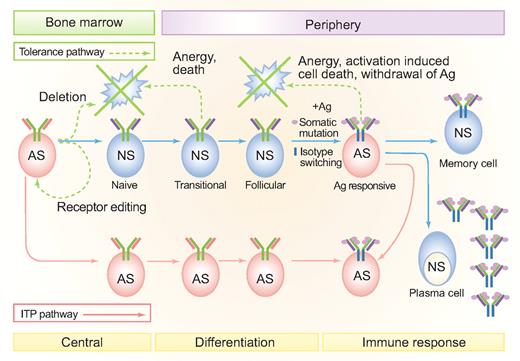

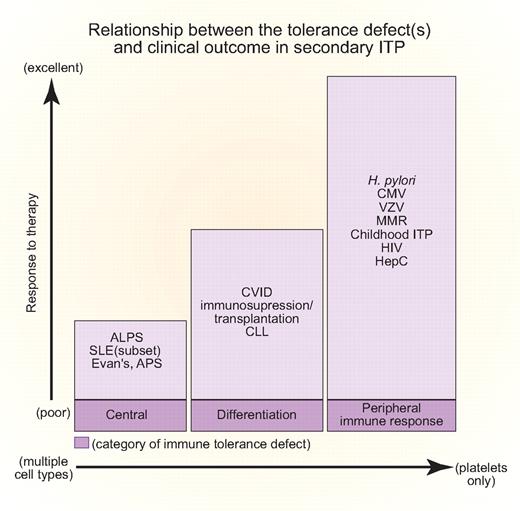

It is unclear how B- and T-cell tolerance is perturbed in primary or secondary ITP. Nevertheless, we propose that the immune tolerance defects in ITP can be classified descriptively into 3 categories: those arising during early development or in the bone marrow (central tolerance defects), differentiation blocks with skewed peripheral B-cell subsets, and peripheral tolerance defects arising in the setting of immune stimulation (Figure 2). We hypothesize that immune thrombocytopenia resulting from defects in peripheral tolerance checkpoints is probably platelet-specific and responsive to ITP-therapy or antigen elimination (Figure 3). Given the relative specificity of the immune response, autoreactivity is less likely to be resurrected rapidly after therapy, although this may occur with late relapses. Conversely, central tolerance defects probably involve additional cell types and may be less responsive to immune-directed therapy because a large proportion of the primary repertoire is autoreactive and may be reconstituted rapidly after therapy.11,12 We will discuss the secondary forms of ITP based on purported immunologic defects and consider how this tolerance checkpoint classification might shed insight into the heterogeneity of primary ITP.

B-cell tolerance checkpoints and loss of self-tolerance in different forms of secondary ITP. Tolerance pathways are denoted by green dashed lines. Solid blue lines represent normal B-cell developmental stages. Where failures in central and peripheral B-cell tolerance might occur in secondary forms of ITP are shown by the solid pink lines. Central B-lymphocyte tolerance checkpoints operate during primary cell maturation in the bone marrow and include clonal deletion and receptor editing. Cross-linking of membrane-bound antibodies on immature B cells leads to apoptosis.122 Antigen receptor specificity is also revised by receptor editing, that is, the continuation or reinitiation of antibody gene rearrangement, usually at light chain loci, in lymphocytes that already have functional antibody.123 Receptor editing can change a self-reactive light chain (shown in pink) to a non–self-reactive light chain (shown in purple). Peripheral tolerance checkpoints monitor and alter the repertoire in lymphocytes that have exited from primary lymphoid organs. Even if central tolerance is perfect, there is a need to regulate peripheral tolerance because somatic mutation can randomly generate autoreactive specificities. Somatic mutations are shown as pink circles on the heavy and light chain V-regions. Heavy chain isotype switching (which usually accompanies somatic mutation during an immune response) is shown by the change in color of the heavy chain constant region from green to blue. Anergy and death of lymphocytes after an immune response also contribute to peripheral tolerance.124 Immune stimulation with a pathogen that mimics self-antigen (molecular mimicry) can also lead to a loss of peripheral tolerance and feed into the antiself ITP pathway. Peripheral AS cells in ITP can arise either primarily, through a defect in central or early tolerance checkpoints, or secondarily as a result of immune stimulation. Autoreactive peripheral B lymphocytes in ITP can include memory cells and plasma cells. Because of space constraints, only the activated cell arising from an immune response for the ITP pathway (not the plasmablast, memory cell or plasma cell) is shown. AS indicates antiself (autoreactive); NS, nonself-reactive; Ag, antigen. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

B-cell tolerance checkpoints and loss of self-tolerance in different forms of secondary ITP. Tolerance pathways are denoted by green dashed lines. Solid blue lines represent normal B-cell developmental stages. Where failures in central and peripheral B-cell tolerance might occur in secondary forms of ITP are shown by the solid pink lines. Central B-lymphocyte tolerance checkpoints operate during primary cell maturation in the bone marrow and include clonal deletion and receptor editing. Cross-linking of membrane-bound antibodies on immature B cells leads to apoptosis.122 Antigen receptor specificity is also revised by receptor editing, that is, the continuation or reinitiation of antibody gene rearrangement, usually at light chain loci, in lymphocytes that already have functional antibody.123 Receptor editing can change a self-reactive light chain (shown in pink) to a non–self-reactive light chain (shown in purple). Peripheral tolerance checkpoints monitor and alter the repertoire in lymphocytes that have exited from primary lymphoid organs. Even if central tolerance is perfect, there is a need to regulate peripheral tolerance because somatic mutation can randomly generate autoreactive specificities. Somatic mutations are shown as pink circles on the heavy and light chain V-regions. Heavy chain isotype switching (which usually accompanies somatic mutation during an immune response) is shown by the change in color of the heavy chain constant region from green to blue. Anergy and death of lymphocytes after an immune response also contribute to peripheral tolerance.124 Immune stimulation with a pathogen that mimics self-antigen (molecular mimicry) can also lead to a loss of peripheral tolerance and feed into the antiself ITP pathway. Peripheral AS cells in ITP can arise either primarily, through a defect in central or early tolerance checkpoints, or secondarily as a result of immune stimulation. Autoreactive peripheral B lymphocytes in ITP can include memory cells and plasma cells. Because of space constraints, only the activated cell arising from an immune response for the ITP pathway (not the plasmablast, memory cell or plasma cell) is shown. AS indicates antiself (autoreactive); NS, nonself-reactive; Ag, antigen. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Relationship between tolerance defect(s) and clinical outcome in secondary ITP. The abscissa indicates whether platelets are the sole hematopoietic lineage affected (right) or whether there is often concurrent hemolytic anemia and immune neutropenia (left). The ordinate indicates responsiveness to treatment of the inciting infection or underlying disease. The proposed corresponding tolerance checkpoint defects are given in shaded boxes at the base of the figure. All of the disease abbreviations are defined in the text. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Relationship between tolerance defect(s) and clinical outcome in secondary ITP. The abscissa indicates whether platelets are the sole hematopoietic lineage affected (right) or whether there is often concurrent hemolytic anemia and immune neutropenia (left). The ordinate indicates responsiveness to treatment of the inciting infection or underlying disease. The proposed corresponding tolerance checkpoint defects are given in shaded boxes at the base of the figure. All of the disease abbreviations are defined in the text. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis.

Diversity of secondary ITP

Our thesis is that the various forms of secondary ITP have different immunologic underpinnings and that a better understanding of the responsible mechanisms could lead to improved, targeted treatment. Each section emphasizes the immunologic abnormalities, with each disorder considered in order of responsiveness, starting with the self-limited. We then consider responsive syndromes with a course similar to primary ITP and end with the most diverse and least responsive disorders that might be caused by defects in central tolerance.

Self-limited and highly responsive forms of secondary ITP

Acute ITP of childhood.

Approximately two-thirds of children with ITP experience a preceding febrile illness. ITP has been attributed to production of platelets expressing viral antigens, binding of immune complexes, generation of antiviral antibodies cross-reactive with platelet antigens, and formation of autoantibodies through epitope spread.13 Thrombocytopenia during the viremic phase may also result from infection of megakaryocytes, altered platelet surfaces that accelerate clearance, hemophagocytosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or a microangiopathic syndrome. Eighty percent of children remit within 6 to 12 months.14

Measles-mumps-rubella vaccine: ITP-MMR.

Acute ITP occurs after vaccinations against several infectious agents. Best studied is measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination, but there is reasonable documentation for acute thrombocytopenia developing after vaccination against pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae B, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

The estimated incidence of ITP-MMR is 1 in 40 000 doses, defined as thrombocytopenia developing within 42 days of exposure,15 an incidence 6-fold higher than acute ITP of childhood. Most cases occur after initial vaccination during the second year of life, and there is a male predominance.15,16 Thrombocytopenia is often severe,16 but responsive to IVIG or corticosteroids. More than 80% recover within 2 months, typically within 2 to 3 weeks,16 with less than 10% evolving into chronic ITP,17 simulating the pattern of acute ITP of childhood.18 The pathophysiology is unknown, although antibodies to GPIIb/IIIa have been identified in few patients,19 similar to primary ITP. Patients in remission or with stable ITP may receive all recommended immunizations,15,16 as the incidence of ITP-MMR is 10- to 20-fold lower than after natural infection. Delays in vaccination are appropriate during resolution of acute ITP or immunosuppressive treatment. The Centers for Disease Control Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has recommended assessing immunity to determine the need for revaccination, although recurrence of thrombocytopenia after revaccination is rare.15

Helicobacter pylori: ITP-HP.

There is strong evidence for an association between infection with HP and ITP.20,21 Active infection is diagnosed using the 13C-urea breath test, finding bacterial antigen in stool, or with gastric biopsy. Antibody testing is insensitive and does not prove active infection, and false positives occur after IVIG.

ITP-HP is defined retrospectively by a durable platelet response to bacterial eradication. Pathogenesis has been attributed to molecular mimicry whereby HP induces antibodies that cross-react with platelets.21,22 HP strains show considerable geographic variation in the cagA virulence gene, which seems to correlate with the incidence of ITP-HP.22,23 In one study, platelet eluates from ITP-HP patients cross-reacted with cagA, recognizing a 55-kDa antigen on ITP-HP platelets, but not on platelets from healthy controls.22

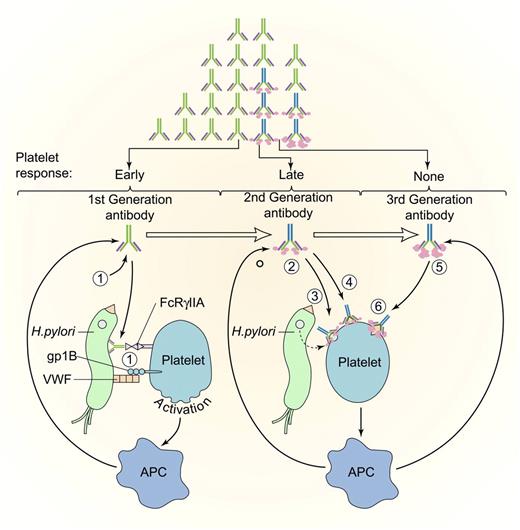

The prevalence of HP infection among ITP patients is comparable to the general population matched for age and location,20,21 although only a small fraction of infected patients develop ITP-HP. Platelet response to documented bacterial eradication ranges from 0% to 7% in 2 US series to 100% in one Japanese series.20 The benefit of bacterial eradication has been established compared with unsuccessful or no eradication.20 Failure to correct thrombocytopenia correlates with T-cell and B-cell clonality, consistent with the emergence of antigen-independent autoreactive clones (Figure 4). HP infection may alter the balance between activating and inhibiting FcγRs.24 Platelet levels often rise within 1 to 3 weeks of antibiotics, before an effect on antibody would be predicted, perhaps attributable to a restoration in this balance. Given the low costs, noninvasive diagnostic methods, and favorable toxicity profile compared with standard ITP therapy, detection and treatment should be considered primarily in populations with a high background incidence of HP, in whom there is a high rate of platelet response to bacterial eradication.

Evolution of antiplatelet antibodies after HP infection. Platelets may be activated by binding of first-generation HP antibodies (1) to platelet FcγIIA or through an interaction between HP-bound von Willebrand factor (VWF) and platelet glycoprotein IB (gpIB). Activation may promote platelet clearance and antigen presentation, which augments production of antibacterial antibodies. Somatic mutation may lead to the development of second-generation antibodies (2) that recognize either bacterially derived factors that bind to platelets (3) or that cross-react with platelet antigens. (4) Improved mucosal permeability or bacterial eradication with proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics may initiate the clinical response in patients with anti-HP antibodies (early response), which may be followed by a decrease in bacterial antigen and reduction in the titer of cross-reacting antibody (late durable response). In patients with protracted disease unresponsive to antibiotic eradication, antibodies to HP may have undergone additional somatic mutations (third-generation antibodies), (5) that lose their reactivity with the inciting antigen but retain platelet reactivity, (6) leading to early relapse or no response. APC indicates antigen-presenting cell. Antibodies (light chains, heavy chains, isotype switching, and somatic mutations) are drawn as in Figure 2. Modified and reprinted with permission. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis and Kenneth Probst.

Evolution of antiplatelet antibodies after HP infection. Platelets may be activated by binding of first-generation HP antibodies (1) to platelet FcγIIA or through an interaction between HP-bound von Willebrand factor (VWF) and platelet glycoprotein IB (gpIB). Activation may promote platelet clearance and antigen presentation, which augments production of antibacterial antibodies. Somatic mutation may lead to the development of second-generation antibodies (2) that recognize either bacterially derived factors that bind to platelets (3) or that cross-react with platelet antigens. (4) Improved mucosal permeability or bacterial eradication with proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics may initiate the clinical response in patients with anti-HP antibodies (early response), which may be followed by a decrease in bacterial antigen and reduction in the titer of cross-reacting antibody (late durable response). In patients with protracted disease unresponsive to antibiotic eradication, antibodies to HP may have undergone additional somatic mutations (third-generation antibodies), (5) that lose their reactivity with the inciting antigen but retain platelet reactivity, (6) leading to early relapse or no response. APC indicates antigen-presenting cell. Antibodies (light chains, heavy chains, isotype switching, and somatic mutations) are drawn as in Figure 2. Modified and reprinted with permission. Professional illustration by Paulette Dennis and Kenneth Probst.

Cytomegalovirus: ITP-CMV.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) commonly causes severe congenital thrombocytopenia and delayed platelet recovery after bone marrow transplantation. CMV can infect megakaryocytes, progenitor cells, and supporting stroma.25 An acute ITP-like syndrome occurs in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed persons. In one series, 3 of 28 children and 3 of 80 adults with typical ITP had CMV in their urine, but there was no correlation between urinary viral clearance and resolution of thrombocytopenia26 ; whereas in another study, platelet counts improved in 4 refractory patients after treatment for CMV.27

Varicella zoster virus: ITP-VZV.

Approximately 5% of otherwise healthy children hospitalized with primary varicella zoster virus (VZV) develop severe thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia occurs in neonates delivered to infected mothers, after vaccination and during viral reactivation.28 Within 5 days of the exanthem, patients present with abrupt onset of bleeding, prominent at extracutaneous sites. Thrombocytopenia may be caused by viral damage to megakaryocytes, adsorption of viral antigens onto platelets, or desialylation of platelet glycoproteins. Thrombocytopenia can be a harbinger of viral dissemination, which can eventuate in purpura fulminans. Exposure to corticosteroids within the preceding 3 months may increase this risk. Spontaneous resolution in nonfulminant cases generally occurs within 2 weeks.28 The utility of antiviral therapy in hastening resolution of thrombocytopenia is unproven.

Less often, thrombocytopenia develops days to several weeks after resolution of infection and is characterized by reduced platelet survival with a normal-appearing bone marrow (ITP-VZV).29 Antibodies to known platelet glycoproteins and uncharacterized platelet antigens that do not cross-react with VZV have been demonstrated.30 Complement-fixing antiviral antibodies that cross-react with approximately 50-kDa and approximately 100-kDa antigens on normal platelets disappear as the infection resolves. ITP-VZV typically resolves spontaneously within 1 to 3 weeks.28,31 Occasionally, the course is protracted and requires ITP therapy.28

Hepatitis C virus: ITP-HCV.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is perhaps the most common chronic viral infection, affecting over 100 million persons worldwide. Serologic evidence of HCV was found in 159 of 799 (20%) of ITP patients in 6 cross-sectional studies from various countries, including the United States.21 Conversely, the incidence of ITP in newly diagnosed HCV patients is higher than expected.32

The pathophysiology of HCV-associated thrombocytopenia is poorly understood and probably multifactorial. The HCV structural protein E2 activates polyclonal B cells by binding to CD81, part of the B-cell coreceptor,33 predisposing to clonal expansion of IgM+κ+IgDlow/−CD21lowCD27+ B cells.34 Antiplatelet glycoprotein antibodies are common, even without thrombocytopenia. Antiviral antibodies, cross-reactive with GPIIIa, have been identified.35

Production of thrombopoietin may be reduced with advanced disease. Infection of megakaryocytes36 may impair platelet production further. In the US experience, HCV-positive patients were older, more often male, and had less severe thrombocytopenia but more major bleeding than did those with ITP.37 In other countries, the clinical characteristics of ITP-HCV were similar to ITP.21 Poor response to corticosteroids was seen in one study, whereas in others response rates exceeded 50%.21,38 Prednisone may increase viral load, hepatic transaminases, and bilirubin.37 IVIG, anti-RhD Ig, and splenectomy are effective, as in ITP.37 In adults receiving interferon-α therapy, platelet counts decrease initially because of impaired production but eventually increase in approximately 50%.37 Initially low platelet counts increased to more than 100 × 109/L in 21 of 23 patients receiving 75 mg daily of an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist (eltrombopag), permitting subsequent combined therapy with pegylated interferon alpha (PEG-INF-α), ribavirin, and eltrombopag.39

Screening is appropriate in patients with risk factors (multiple sex partners, intravenous drug abuse, blood transfusions) or where the background prevalence of infection is high. Corticosteroids should be avoided or discontinued. Anti-HCV combined with ITP-specific therapy should be considered, even without overt liver disease.21,37,39

Human immunodeficiency virus: ITP-HIV.

ITP-HIV (platelet count < 150 × 109/L) was reported in 5% to 30% of infected patients before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).21 The 1-year incidence of ITP-HIV (platelet count < 50 × 109/L) was 3.7% among 36 515 participants in the Multistate Adult and Adolescent Spectrum of Disease Project, which increased in frequency and severity with disease progression (1.7% without AIDS, 3.1% with immunologic AIDS [CD4 lymphocytes < 200/μL] and 8.7% with clinical AIDS).40

Multiple mechanisms contribute to ITP-HIV, including accelerated platelet clearance and suppressed platelet production. Sera contain antibodies against viral proteins (nef, gag, env, pol, GP160, and p24), some of which cross-react with amino acids 44 to 66 of GPIIIa. Anti-idiotypic antibodies have also been identified that prevent thrombocytopenia from developing in vivo.41 Anti-GPIIb/IIIa antibodies fragment platelets by activating NADPH oxidase, generating peroxide and other reactive oxygen species through platelet phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase42 ; fragmentation is inhibited by dexamethasone, which impedes enzyme translocation to and from the plasma membrane. Megakaryocytes express CD4 and coreceptors for HIV, internalize HIV, and express viral RNA.43 During disease progression, impaired platelet production by cytopathic infection of megakaryocytes predominates.44,45 The centrality of viral antigens in the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia is supported by the response of the platelet count to HAART.

Patients may present with isolated thrombocytopenia indistinguishable from ITP years before developing AIDS.21,40 As the disease progresses, the prevalence and severity of thrombocytopenia correlate with viral load and response to HAART.46,47 ITP-HIV generally responds to ITP therapy. Short-term treatment with prednisone appears safe and effective, as does splenectomy.48,49 Higher response rates and prolonged responses are more common with anti-D than with IVIG.50 Response rates are lower among intravenous drug users, possibly reflecting coinfection with HCV.

Differentiation blocks in secondary ITP

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: ITP-CLL.

The most common neoplastic processes linked to ITP involve the hematopoietic compartment, although rare patients with solid tumors have been reported. ITP develops in 1% to 5% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), an incidence approximately one-tenth that of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AHA).51-53 Older age and advanced stage are independent risk factors for AHA, but the predictive value of these risk factors for ITP-CLL is less apparent.54 ITP occurs a mean of 13 months from the diagnosis of CLL but may precede it or develop at any time. Indeed, small CD19/CD5-positive clones may be found in bone marrow from older patients with ITP.51,55

ITP-CLL is associated with a higher frequency of unmutated IgVH genes, more frequent involvement of the VH1 family, and shorter 5-year survival.54 There is no evidence the malignant clone is responsible for antibody production. ITP-CLL may also be precipitated by fludarabine or other purine analogs that accelerate loss of CD4+, CD45RA+ cells.53 There is concern about using purine analogs to treat ITP based on experience in AHA.53 ITP-CLL is somewhat less responsive to IVIG and prednisone,54 but promising results have been obtained with rituximab and cyclosporine.53

Hodgkin disease: ITP-HD.

The prevalence of ITP–Hodgkin disease (HD) is estimated at 0.2% to 1%, with most cases occurring after the diagnosis of HD.56,57 In the British National Lymphoma Investigation Registry, 8 of 4090 patients with HD developed ITP after a median of 23 months,57 including 6 in remission. ITP often responds to treatment of HD and is rare in patients who have been in remission for many years.58 ITP is estimated to occur in 0.76% of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma without CLL and often precedes the diagnosis of lymphoma (n = 1850 non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients).59

Large granular T-lymphocyte leukemia: ITP-LGL.

Large granular T-lymphocyte leukemia (LGL) is a clonal proliferation of mature CD8+ T lymphocytes. Clonal populations of LGL cells are also detected in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and modest increases occur in some patients with ITP.60 Neutropenia, anemia, and mild thrombocytopenia are common in LGL leukemia. It is not clear whether the mechanisms underlying ITP in LGL leukemia, wherein LGL clonality and increases in the absolute CD8 count are sustained, are similar to reactive conditions in which the LGL count may be transiently or cyclically elevated.61 Severe thrombocytopenia, observed in approximately 1%,60 may result from suppression of megakaryopoiesis by LGL-mediated cytotoxicity.62 Treatment is directed against the LGL clone, using cyclophosphamide or cyclosporine.60,62

Common variable immune deficiency: ITP-CVID.

Common variable immune deficiency (CVID) is an uncommon (1 in 50 000 persons) heterogeneous disorder characterized by defects in late stages of B-cell development. Clinical manifestations include recurrent infection, allergy, and autoimmunity. The diagnosis is established by persistent reduction in serum immunoglobulins and insufficient antibody response to protein and polysaccharide antigens. Recurrent sinopulmonary tract infections or systemic granulomas occur in 70% to 80% of patients. Recognition is often delayed because of diverse and subtle symptoms. Mortality is generally related to progressive bronchiectasis or pulmonary granulomas or the development of lymphomas, the latter being more common in women older than 60 years.

More than 20% of patients develop an autoimmune disorder, most commonly involving hematopoietic cells. ITP, often severe (median platelet count, 20 × 109/L), occurs in approximately 10% of patients, often accompanied by AHA and occasionally autoimmune neutropenia.63,64 There is no gender predilection. The median age at onset of ITP is approximately 23 years but may occur at any age.65 Disease onset precedes the diagnosis of CVID by a mean of 4 years64,66 but may also be diagnosed contemporaneously or after treatment for CVID has begun.

The pathogenesis of autoantibody production is unknown. Studies in small numbers of CVID patients suggest that defects at either of 2 B-cell tolerance checkpoints contribute to autoantibody production. Polymorphisms in the B-cell transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating interactor are linked to CVID and especially to development of ITP or AHA.67 In other studies, the propensity to develop ITP or AIHA correlates with a deficiency in isotype-switched memory B cells (CD27+/IgM−/IgD−).68 An associated inability to eradicate microbes is posited to exacerbate tissue damage, expanding production of cross-reactive antibodies in the face of deficient T- or B-cell peripheral control mechanisms. IVIG therapy may promote up-regulation of regulatory T cells.69 ITP is also associated with other immunodeficiency states, including DiGeorge syndrome, IgA and complement (C4) deficiency, and probably Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, but not Bruton X-linked agammaglobulinemia where B cells are absent.

CVID-ITP patients respond to corticosteroids, IVIG, and anti-D64, but prolonged steroid use is associated with fungal infections and the use of anti-D may be precluded by concurrent AHA. Hence, IVIG is the mainstay of therapy. Rarely, anaphylaxis resulting from IgE–anti-IgA antibodies necessitates the use of IgA-depleted IVIG preparations. Two-thirds of patients respond initially to splenectomy, but concern over sepsis complicates the decision to operate or to use immunosuppression.63,64,70 Rituximab combined with IVIG appears beneficial in some patients.70 Fewer patients develop ITP while on IgG replacement,63,64 suggesting that early diagnosis and therapy are useful.63

Central tolerance defects in secondary forms of ITP

Autoimmune lymphoproliferative (Canale-Smith) syndrome: ITP-ALPS.

Autoimmune lymphoproliferative (Canale-Smith) syndrome (ALPS) is an inherited disorder characterized by defective B- and T-lymphocyte apoptosis. Eighty-five percent of patients have mutations in the APT1 gene encoding Fas (CD95/Apo-1); others have mutations in genes encoding Fas ligand (Fas-L), caspase-8, or caspase-10; the underlying defect has not been identified in the remainder. Criteria for diagnosis include chronic nonmalignant lymphadenopathy and (hepato)splenomegaly, defective Fas-mediated T-cell apoptosis, and more than 1% TCRα/β+, CD3+, CD4−, CD8− (double-negative) T cells in peripheral blood or lymphoid tissue.71 Supporting features include autoantibodies and a family history of ALPS. The median age at presentation is 2 to 3 years, but the disease can present (rarely) in adulthood.

Homozygous deletion of Fas or Fas-L in lpr and gld mice, respectively, leads to lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity, but not to immune cytopenias. Expression of clinical disease in humans is more complex. Although defects are most commonly inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, penetrance is variable. Clinical expression correlates with dominant-negative mutations that interfere with ligand/receptor trimerization and signal transduction. The observation of healthy family members with similar mutations and in vitro defects suggests involvement of additional genes or environmental factors (eg, altered interleukin-2/interleukin-2 receptor regulation leading to loss of CD25+/CD4+ T cells,72 among others). B cells express Fas when activated, becoming sensitive to killing by Fas L-expressing T cells. However, the pathophysiologic relationship between these mutations and the tendency to form autoantibodies to hematopoietic cells is not established.

Hepatosplenomegaly, and to some extent lymphadenopathy, tends to regress with age, whereas autoimmunity typically persists. Approximately 20% develop ITP and/or AHA (blurring the distinction between ITP-ALPS and Evans syndrome [ES], ie, ITP-ES71 ) and/or neutropenia, presumed immune in origin.72 Thrombocytopenia responds less well than primary ITP to corticosteroids, IVIG,or splenectomy, and immunosuppression may increase the risk of infection. Initial experiences with rituximab73 and mycophenolate mofetil74 are promising. Responses to pyrimethamine/sulfadioxine and bone marrow transplantation are reported. Progressive hypogammaglobulinemia may develop into a picture similar to CVID. Patients have a propensity to develop B-cell lymphomas.

Evans syndrome: ITP-ES.

ITP-ES (coincidence of ITP and warm AHA) occurs in approximately 0.7% of patients with ITP.75 There is no gender preference. Thrombocytopenia can precede the development of AHA by years, delaying diagnosis, occur concomitantly, or develop sometime thereafter. Approximately 50% of ITP-ES patients develop neutropenia and 5% to 10% develop pancytopenia.75,76 The red cell antibodies are directed at the Rh locus with rare exceptions and are serologically distinct from platelet-reactive antibodies. ITP-ES may follow bone marrow or solid organ transplantation, exposure to fludarabine or other drugs, and in association with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), CLL, and ALPS. Elution studies are needed to distinguish autoantibodies from prior therapy with anti-D.

New evidence suggests that ITP-ES may involve broader autoimmunity with partial penetrance. In one study, 50% to 60% of ITP-ES children met criteria for ALPS.71 IgG or IgA deficiency, eczema, alopecia, or other autoimmune conditions may develop.

ITP-ES often follows a remitting-relapsing course or cytopenias may persist. Responses and exacerbations of AHA and ITP are often discordant; immune hemolysis may protect platelets from phagocytosis. Responses to corticosteroids and IVIG are transient and splenectomy is often ineffective.77 Therefore, early recognition is important as somewhat higher response rates are reported with combination therapy, rituximab, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate mofetil78,79 and some respond to transplantation. Nevertheless, mortality rates may approach 30% to 35% resulting from hemorrhage or sepsis.75

Antiphospholipid syndrome: ITP-APS.

Many patients present with thrombocytopenia and antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs). When both are present, 3 questions arise: (1) Does thrombocytopenia result from activation of coagulation or from platelet antibodies? (2) Do APLAs identify patients at risk for thrombosis? (3) Should treatment be altered?

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is defined by venous or arterial thrombosis or recurrent pregnancy loss in the presence of APLAs (lupus anticoagulant or high titers of anticardiolipin or anti–β2-GPI-1 antibodies on at least 2 measurements made at least 12 weeks apart). APS may be secondary to SLE or related disorders or primary when no underlying disorder is apparent. Approximately one-third of patients with primary APS develop thrombocytopenia, generally mild to moderate. Severe thrombocytopenia may correlate with risk of thrombosis.80 Platelets may rise in response to anticoagulation given for a systemic thrombotic diasthesis (catastrophic APS). Patients with thrombocytopenia and antiprothrombin antibodies are susceptible to bleeding.

Several proposed mechanisms contribute to immune thrombocytopenia. APLAs bind anionic phospholipids and diverse phospholipid-binding proteins, for example, beta-2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI-1), with low affinity. Anti–β2-GPI-1 antibodies dimerize the antigen, which increases the avidity of antibody binding. Anti–β2-GPI-1 forms complexes between GPIbα and a splice variant of the apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (apoER2′).81-83 Cross-linking of anti–β2-GPI-1 stimulates phosphorylation of apoER2′, activates p38 MAP kinase, generates thromboxane A2, and activates phosphatidylinsolitol-3-kinase and Akt pathways through GPIbα, sensitizing platelets to other agonists. Some APLAs bind to anionic epitopes on GPIIIa, whereas others recognize phosphatidylserine translocated from the inner to the external plasma membrane when platelets are activated, creating a positive feedback loop.84

It is uncertain whether APLAs accelerate platelet clearance in vivo. Serologically distinct antiplatelet GP antibodies with specificities seen in ITP are also found in APS, and these correlate with thrombocytopenia more closely than APLAs.85 Moreover, 10% to 70% of patients with ITP have one or more APLAs, depending on disease activity and the extent of the search.86

There is no compelling reason to assess patients with typical ITP for APLAs. APLAs do not alter response to ITP therapy.86,87 It is uncertain whether APLAs increase the risk of thrombosis during response to ITP therapy.86,87 Although finding APLAs per se does not alter management of primary ITP, patients with APS may require higher platelet counts than are otherwise necessary (> 40-50 × 109/L) to manage anticoagulation used to prevent thrombosis or fetal loss.

Systemic lupus erythematosus: ITP-SLE.

Thrombocytopenia, generally not severe,88 develops in approximately one-third of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients at some time during their illness, whereas SLE develops in 2% to 5% of ITP patients (usually female) who are followed for years.89,90

The pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia is multifactorial and includes antibodies to platelet glycoproteins (as in ITP), DNA, phospholipids and phospholipid binding proteins, CD40 ligand,91 thrombopoietin and its receptor,92 immune complexes of diverse composition, and impaired FAS-FAS ligand–mediated apoptosis. Thrombocytopenia may also be caused or exacerbated by systemic vasculitis, hemophagocytosis, thrombotic microangiopathy, amegakaryocytosis, and marrow damage.

The clinical course and response to medical management of isolated thrombocytopenia are similar to ITP,88,93 whereas severe thrombocytopenia that develops during an exacerbation of vasculitis portends a poorer prognosis,94 requiring aggressive treatment of the underlying disease.95 Maintenance treatment should be limited to prevention of bleeding. Patients with severe SLE are less likely to respond to splenectomy than those with primary ITP.96 Reliance on splenectomy should be tempered by frequent requirements for corticosteroids or immunosuppressants to control other manifestations of SLE and is indicated when thrombocytopenia is severe, persistent, is the predominant reason for treatment, or if other tolerable options are ineffective and the underlying disease is otherwise controlled.97

Posttransplantation: ITP-Tx.

ITP and ITP-ES may develop after allogeneic or autologous bone marrow, umbilical cord progenitor cell, peripheral blood, and solid organ transplantation. ITP-Tx is a heterogeneous entity with an onset from 1 day to more than 1 year after the procedure and with a clinical course spanning unresponsive, relentless, and fatal,98 to one typical of chronic ITP or spontaneous resolution. The best documented cases result from mixed chimerism with host alloantibodies directed to polymorphic determinants on donor platelets, for example, HPA-1a. Less commonly, the donor had overt or presumptive ITP99 or autoantibodies develop de novo in the context of immunosuppression and chronic infection. Thrombocytopenia in this setting may result from graft-versus-host disease or persistent infection, for example, CMV, which require different approaches to management.

Heterogeneity of primary ITP

Variation in pathogenesis and management of secondary forms of ITP may provide insight into the heterogeneity of what is currently designated “primary ITP,” a diagnosis of exclusion. Much of what follows is speculative because definitive studies have not been completed in several areas.

Consensus guidelines for primary ITP refer to patients with isolated thrombocytopenia (platelet counts < 150 × 109/L).100,101 However, only 7% of 217 persons meeting these criteria with platelets between 100 and 150 × 109/L developed more severe thrombocytopenia over a mean of 64 months; platelets normalized without intervention in 11% and remained stable in the rest.102 Other explanations may exist for mild thrombocytopenia meeting the criteria of ITP, and it may be inappropriate to presume the diagnosis in this setting.103

Recent surveillance studies challenge the long-held notion that ITP is predominantly a disorder of young women; rather, the disease was reported to show a progressive increase in incidence with age and a gender balance in the older population,104 with mean platelets counts of approximately 20 × 109/L, excluding incidental detection during other investigation. It is unclear whether these findings reflect changes in demographics or better detection because population-based studies were unavailable before 2000. The demographics of ITP may be mutable and show regional differences because of emergence of predisposing infections, increase in immune deficiency in aging populations, and increased survival from B-cell neoplasms.

Initiation of the immune response

The prevalence of ITP after infections that prompt production of cross-reactive antibodies (eg, HIV, HCV, HP), association with diverse immunodeficiency states (eg, CLL, CVID, and ALPS), and the co-occurrence of specific autoantibodies (ES, APS) suggests that the predisposition to form platelet autoantibodies results from several mechanisms.

Molecular mimicry

As discussed, some cases of ITP-HIV, ITP-VZV, and ITP-HCV are associated with antiviral antibodies that cross-react with platelet GPIIb/IIIa. The variable incidence of ITP-HP has been attributed to variation in virulence genes that evoke cross-reactive antibodies. The clinical course of ITP-MMR and acute ITP in childhood suggests a similar etiology.

Perturbation of the immune repertoire

Although platelet glycoproteins are subject to proteolysis, posttranslational modification, internalization, and shedding, no intrinsic or acquired abnormalities have been identified to cause platelets to appear as foreign to the immune system. GPIIb/IIIa is expressed on thymic epithelial cells, and no intrathymic defect in tolerizing high-affinity autoreactive T-cell clones has been identified. It is also not known whether some patients with ITP have a central B-cell tolerance defect or whether loss of peripheral tolerance mediates acute or chronic ITP. As yet unidentified exogenous antigens might induce loss of peripheral tolerance and promote development of self-reactive antibodies in settings where proinflammatory cytokines and interferon-γ are up-regulated or counterregulatory processes are disrupted through loss of T-regulatory cells, failures in B-cell tolerance, or alterations in cytokines or chemokines.

As discussed, patients often have a cytokine profile consistent with CD4+ Th0/Th1 activation associated with reduced peripheral Th2 and T-regulatory cells and impaired susceptibility to apoptosis. Although this pattern promotes antigen presentation and might amplify and propagate self-reactive clones, it is neither specific for ITP nor universal. There is as yet limited evidence that T-cell defects precede the onset of disease,105 anticipate clinical course,5 provide prognostic information, or modify response. Reversion to a Th0/Th2 cytokine gene profile after treatment with IVIG correlates with remission in childhood ITP,106 and Foxp3 mRNA and the T-cell receptor Vβ repertoires normalize in splenectomy or rituximab responders,6 raising uncertainty about causation versus effect of therapy.

Amplification of the autoimmune response

Platelets are involved in inflammation and innate immunity. ITP T cells recognize cryptic epitopes generated from GPIIb/IIIa and probably other platelet proteins. The hierarchy of peptides recognized by T cells varies, and only some are recognized by T cells from healthy controls.107 Are these peptides generated by inflammatory stimuli or platelet turnover accelerating normal pathways of cellular processing in antigen-presenting cells or might minor pathways generate novel immunogenetic peptides under these conditions?

ITP antibodies also vary in antigen specificity.1 Limited epitope spread, whereby antigen processing initiated by antibody to one platelet determinant promotes generation of additional antigens derived from other platelet proteins,13 is suggested by the multiplicity of structurally distinct platelet-specific epitopes that become targets, the diversity of immunogenic peptides recognized, and the development of T-cell clones that recognize transmembrane and cytoplasmic determinants.107 Platelets may augment this process when they: (1) undergo apoptosis108 ; (2) are activated by antibody to express major histocompatibility complex class II,109 CD154 (CD40L),110 and CD80 (B7-1); (3) release sCD40L and proinflammatory cytokines (eg, MCP-1 and RANTES); or (4) by immune complex-mediated activation of antigen-presenting cells108 via Fcγ receptors.

Auxiliary pathways

Platelet antibodies are not detected in all patients, and anti-CD20 and other immunosuppressive agents only induce durable complete remission in the minority, notwithstanding prolonged and extensive depression in circulating B cells. Plasma cells and some tissue-based B-cell populations are resistant to depletion. In addition, loss of B-cell antigen presentation may not correct defects in central tolerance and T-cell education. Moreover, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which in some patients express increased Apo-1/Fas, granzymes A and B, perforin, and reduced killer cell Ig-like receptors, can lyse platelets in vitro.111 Increased numbers of VLA-4+CD3+C8+ T cells expressing the homing receptor CX3CR1 were found in ITP bone marrow.112 It is uncertain whether these findings precede disease onset, whether sufficient effector/target ratios are attained to impair platelet production, and how often these findings impact the clinical picture.

Evolution of the immune response.

The clinical course of ITP is variable. Some patients relapse months to years after splenectomy-induced remission, whereas others develop hemostatic platelet counts years after failing diverse modalities.113 This suggests an unstable balance between antibody production and containment, immune complex clearance, and platelet production, especially evident in patients with cyclic immune thrombocytopenia. The presence of oligoclonal peripheral T-cell populations, defined by CDR3 spectratyping, appears to correlate directly with disease duration6 and inversely with response to splenectomy114 and rituximab.6 Peptides recognized by ITP T cells also change over time, with implications for induction of tolerance.107 GPIIb/IIIa-reactive antibodies cloned from ITP spleens show a pattern consistent with limited VH gene usage but also with antigen-driven somatic mutation.3 Somatic mutations in antipathogen antibodies accompanied by clonal exhaustion could cause autonomous clones to emerge that do not resolve on successful elimination of inciting antigen (eg, HP, Figure 4).115 Mechanisms mediating remission in childhood ITP are unstudied.

Variations in pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia

Enhanced platelet clearance.

Approximately two-thirds of patients achieve a durable response to splenectomy. But what of the one-third who fail, including those who relapse years later? Platelet antibodies have not been shown to consistently predict response to any intervention. Nor is it known whether impaired platelet production is responsible. FcRγIIc expression, involved in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, is more prevalent in ITP patients. Response to corticosteroids is affected by polymorphisms in FcRγIIIa. FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is up-regulated by platelet-bound lipopolysaccharide116 and probably other intermittent environmental stimuli (eg, hormones), and down-regulated by platelet CD47. Antibody-mediated platelet activation may accelerate clearance through apoptosis or opsonization by inducing signals such as phosphatidylserine or P-selectin–PSGL1. Anti-GPIIIa antibodies in ITP-HIV lyse platelets through a peroxide-mediated process. Hyperthyroidism, present in approximately 5% of ITP patients, is associated with reduced platelet survival; platelet counts may improve once a euthyroid state is restored.117

Impaired platelet production.

Platelet production is variably impaired,118 possibly contributing to failure of splenectomy or therapy directed at attenuating peripheral clearance. Antibodies may impair megakaryocyte development, induce apoptosis, impede platelet release, or promote intramedullary phagocytosis.118 ITP plasmas differ in their ability to inhibit megakaryopoiesis in vitro,119 in part related to differences in antigen specificity. The effects of cytolytic T cells or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity on platelet production, especially in refractory disease, are uncertain. Genetic or acquired limitations in megakaryocyte and platelet production, susceptibility to antibody- or cell-mediated intramedullary apoptosis,120 or heterogeneity in intracellular signal transduction pathways are largely unexplored.

Clinical heterogeneity

Propensity to bleed.

Some patients develop recurrent epistaxis, frequent ecchymoses, or other bleeding manifestations at platelet counts of 20 × 109/L, whereas others rarely bleed, notwithstanding values less than 5 × 109/L. Infrequently, ITP antibodies initiate antigen shedding and inhibit specific glycoprotein functions. It is unclear whether the bleeding propensity correlates with platelet size, maturity, or specific activity. Disease modifiers that foster or mitigate bleeding (eg, factor VIIIc, α-granule content) have not been identified. Vascular inflammation promotes thrombocytopenic bleeding; thus, endothelial function merits further study. There is also no biochemical explanation for the marked fatigue that may be associated with low platelet counts

Risk of thrombosis.

There is no consensus whether ITP is intrinsically a procoagulant disorder,121 especially during rapid platelet response, manifested by platelet activation, and release of platelet microparticles. As discussed, the literature is conflicting whether coexisting APLAs predispose to thrombosis. Absent compelling data, these concerns mitigate in favor of treating to attain a hemostatic, but not a normal, platelet count in most patients and to consider use of aspirin in patients at risk for thrombosis who attain stable counts more than 50 000/μL (50 × 109/L).

Perspective

Essentially all studies of incidence, demographics, pathophysiology, and treatment address ITP as a single entity. Yet, lessons learned from secondary forms suggest that primary ITP is heterogeneous as well. Primary idiopathic disease will comprise an ever-decreasing proportion of patients as specific inciting events and immune defects are better identified. Improved stratification predicated on systematically identified tolerance checkpoint defects, dysfunctional auxiliary pathways, and inciting antigens will help define prognosis and target intervention. What is lacking because of the highly specialized nature of scientific research is the capacity to study the same cohort of patients for T- and B-cell repertoire, genetic markers of immune susceptibility genes, antibody specificity and avidity, platelet kinetics, platelet proteome, and longitudinal outcome. More rapid progress requires a consortium to assemble a large international cohort for prospective study and sharing of sequentially obtained, archived, and clinically annotated samples. ITP provides an opportunity to further our understanding of how otherwise healthy persons generate tissue-specific autoantibodies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD; U01 DK 070430 and R01 DE017590; HL081012, D.B.C.; 1U01 HL72196-01-05; 1U01 HL72196-01; and UL1 RR024996), the Children's Cancer and Blood Foundation (New York, NY; J.B.B.), and Alliance for Lupus Research (New York, NY; E.T.L.P.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed directly to the literature review and to the drafting of the manuscript itself.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.B.C. has served on advisory boards for Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Baxter, Biogen, Syntonix, and Shionogi. H.A.L. had research support from Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Immunomedics and consulted with Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Baxter. J.B.B. owns stock valued at greater than $10 000 but less than $100 000 in Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline; has served on advisory boards for Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Ligand, and Baxter; and has clinical research support from Baxter, Cangene, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, Ligand, Sysmex, and Genzyme. E.T.L.P. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Douglas B. Cines, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 513A Stellar-Chance, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: dcines@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal