Abstract

Human protein S is an anticoagulation protein. However, it is unknown whether protein S could regulate the expression and function of macrophage scavenger receptor A (SR-A) in macrophages. Human THP-1 monocytes and peripheral blood monocytes were differentiated into macrophages and then treated with physiological concentrations of human protein S. We found that protein S significantly reduced acetylated low-density lipoprotein (AcLDL) uptake and binding by macrophages and decreased the intracellular cholesteryl ester content. Protein S suppressed the expression of the SR-A at both mRNA and protein levels. Protein S reduced the SR-A promoter activity primarily through inhibition in the binding of transcription factors to the AP-1 promoter element in macrophages. Furthermore, human protein S could bind and induce phosphorylation of Mer receptor tyrosine kinase (Mer RTK). Soluble Mer protein or tyrosine kinase inhibitor herbimycin A effectively blocked the effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the level of protein S was substantially increased in human atherosclerotic arteries. Thus, human protein S can inhibit the expression and activity of SR-A through Mer RTK in macrophages, suggesting that human protein S is a modulator for macrophage functions in uptaking of modified lipoproteins.

Introduction

Protein S is a vitamin K–dependent plasma glycoprotein that serves as a key cofactor for the anticoagulant activity of activated protein C.1 In humans, protein S is synthesized mainly by hepatocytes, but also by megakaryocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells.2 Protein S normally circulates in human plasma at a concentration of approximately 25 mg/L in free form and in complex with C4b-binding protein (C4BP). The critical antithrombotic role of protein S is revealed by the massive thrombotic complications suffered by infants homozygous for protein S deficiency.3 Adult patients with mild heterozygous deficiencies in protein S are associated with risk for venous and arterial thrombosis,4,5 ischemic stroke,6 cerebral thrombophlebitis,7 myocardial infarction, and vascular calcification.8,9 Protein S infused in a murine model of ischemic stroke decreases infarction and edema volumes.10 However, 2 epidemiologic studies have shown that human plasma protein S concentration is positively correlated with risk of coronary heart disease.11,12 Clinical studies have also demonstrated that protein S is associated with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins of human plasma, binds with high-affinity to very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) receptor on macrophages, and induces foam cell formation.13 Immunohistochemistry experiments show that protein S localizes in atherosclerotic coronary lesions.14 Although these findings suggest the involvement of protein S in atherosclerosis and atherothrombosis, direct evidence of a causal relationship between protein S and vascular disease is very limited, and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined

Protein S and its structural homologue, growth arrest–specific gene-6 (Gas6), may be the ligand for the Tyro3/Ax1 family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs).15,16 However, it is not fully understood what the cellular expression and functions of these RTKs are. Surprisingly, only limited studies have reported the nonanticoagulant functions of protein S.10,17,18 Human protein S was shown to be a mitogen for vascular smooth muscle cells18 and a stimulator for macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.17 The physiologic relevance of human protein S interacting with macrophages or other tissue cells is important but remains largely unknown.

Atherothrombosis, defined as atherosclerotic lesion disruption with superimposed thrombus formation, is the leading cause of mortality in the developed countries. In the atherosclerosis formation, the circulating monocytes are recruited to the arterial wall, wherein they transform into macrophages and foam cells through the increased uptake of modified LDL by scavenger receptors such as macrophage scavenger receptor A (SR-A).19 SR-A plays critical roles in modified LDL uptake as well as in clearance of debris including necrotic and apoptotic cell fragments in the vessel wall.20 However, the endogenous regulators of SR-A expression are not fully elucidated.

In this study, we used an in vitro model to address whether protein S could affect SR-A function and expression, and which receptors, transcription factors, or signaling transduction pathways could be involved. We also performed immunohistochemistry analysis to detect the expression of protein S in human atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic arteries. This study demonstrates a new function of human protein S, which may play a critical role in the atherothrombotic disease.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Human protein S was obtained from American Diagnostica (Stamford, CT). It was purified from fresh frozen human plasma via immunopurification and characterized by no protein S-C4BP complex, a single band at 69-kDa on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and no reduction upon incubation with 2-mercaptoethanol. Other reagents, and detailed materials and methods can be found in Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cell culture

Human monocytic cell line (THP-1) cells, human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cell line (U937) cells, and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were differentiated into macrophages, and then treated with protein S.

AcLDL uptake and binding

For acetylated low-density lipoprotein (AcLDL) uptake assay, protein S–treated human macrophages were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL (5 μg/mL) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% lipoprotein-deficient human serum at 37°C for 3 hours.21 For the binding experiment, THP-1 macrophages were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes because lowering the temperature can inhibit endocytosis of SR-A ligands. Unlabeled AcLDL in an excess amount (50-fold) was added together with the fluorescent AcLDL for competition assay. At the end of incubation, the cells were lysed with 0.1% SDS/0.1 N NaOH for direct measurement of fluorescence and protein concentrations. The fluorescence of each well was measured in triplicate by a fluorescence reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). The excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 485 and 528 nm, respectively. Specific fluorescent intensity was determined by subtracting mean fluorescent intensity of unlabeled cells (autofluorescence) from that of Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL–incubated cells. Specific uptake (or binding) was calculated by subtracting uptake (or binding) in the presence of an excess amount of unlabeled AcLDL from the total uptake (or binding) in the absence of unlabeled AcLDL.

Analysis of cellular cholesterol content

The cholesterol content was quantified with a cholesterol assay kit from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, GA). The amount of cholesterol ester was calculated by subtracting the free cholesterol from total cholesterol.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Western blot and immunodepletion of protein S

Western blot analysis and immunodepletion were performed as previously described.17 The cell lysates (40 μg protein/lane) were applied to a SDS–PAGE. Primary antibodies against human protein S, SR-A, Axl, Tyro3, Mer, and β-actin were used. For the protein S immunodepletion experiment, rabbit antihuman protein S, normal rabbit IgG, mouse monoclonal antihuman protein S, or normal mouse IgG was used.

SR-A promoter activity assay

SR-A promoter fragment was kindly provided by Dr Christopher K. Glass (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA).23,24 The promoter fragment (from −630 to +48 bp) was subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector carrying firefly luciferase. SR-A promoter mutants were created by site-directed mutagenesis of the positive transcriptional elements corresponding to the PU.1 site at −198 to −185 bp, and activator protein 1 (AP-1) element at −67 to −50 bp, as previously described.24 THP-1 cells were cotransfected with pGL3-Basic-SR-A constructs and pRL-SV40 vector carrying Renilla luciferase (as an internal control reporter) by electroporation (nucleofector program V-01/V-001) in cell line nucleofector solution V (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). After transfection, the cells were differentiated with 50 ng/mL PMA for 24 hours. THP-1 macrophages were then treated with 20 μg/mL protein S for 24 hours. Luciferase activity was measured using a dual luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and a luminometer. Luciferase activities were normalized by the ratio of firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

EMSA

Cellular nuclear extracts were prepared. Biotin end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing consensus sequences of AP-1, Ets, and PU.1 were used. The biotin-labeled DNA–nuclear protein complexes were subjected to a 6% native PAGE analysis by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) kit (Panomics, Redwood City, CA).

Tyrosine phosphorylation assay

THP-1 macrophages were treated with human protein S (20 μg/mL) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with goat anti-Axl, anti-Tyro3, or anti-Mer antibody, and immunoblotted with a phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody (4G10; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), anti-Axl, anti-Tyro3, or anti-Mer antibody, respectively.

Binding assay of human protein S to Mer/Fc fusion protein

Purified human protein S (10 nM) was mixed with 10 nM Mer/Fc or tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB)/Fc at 4°C for 2 hours. Protein A agarose beads were added and complexes were incubated for an additional 1 hour. Bound proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–protein S antibody.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Formalin-fixed specimens of human aorta, and carotid and coronary arteries were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA). Immunohistochemistry was performed. Images were taken with an Olympus BX41 microscope with a SPOT camera. The protocol of use of human tissues obtained from NDRI was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Baylor College of Medicine. The investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean plus or minus SD. Statistical comparison was performed using the Student t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A probability (P) value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Human protein S inhibits AcLDL uptake and binding in human monocyte–derived macrophages

THP-1 was used in the study. Phorbor 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)–untreated suspension monocytic cells are referred to monocytes, and PMA-differentiated adhesion cells are referred to macrophages. To evaluate whether protein S could affect SR-A activity in human monocyte–derived macrophages, we treated human macrophages with human protein S for 24 hours, and then measured the Alexa Fluor 488-AcLDL uptake using a fluorescence microplate reader. We observed that human macrophages treated with physiological concentrations of protein S significantly reduced the uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-AcLDL in a concentration-dependent manner (n = 3; P < .05; Figure 1A). Decreased uptake of fluorescent AcLDL in the protein S–treated THP-1 macrophages was also directly visualized under the fluorescent microscope compared with control cells (Figure 1B). Since human protein S was in the glycerol-containing buffer, we performed additional experiments with glycerol buffer for negative controls. We collected glycerol buffer after centrifuging the protein S solution through micron ultracel YM-10 column (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and then tested the effects of glycerol (from 0.125% to 0.5%) on AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophage. The AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophage was not changed by glycerol (Figure S1). Two other sources of human protein S (USBiological [Swampscott, MA] and Calbiochem [San Diego, CA]) were also tested. The protein S from other different sources has shown similar inhibitory effects on AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure S2).

Inhibitory effects of human protein S on AcLDL uptake and binding by human monocyte–derived macrophages. (A,B) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity of cells was measured with a fluorescence microplate reader and photographed with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX51 with SPOT camera; total magnification ×200). (C) AcLDL binding to THP-1 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 30 minutes at 4°C. (D) AcLDL uptake in U937 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (E) AcLDL uptake in human PBMC–derived macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. Columns and bars denote the mean and SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls.

Inhibitory effects of human protein S on AcLDL uptake and binding by human monocyte–derived macrophages. (A,B) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity of cells was measured with a fluorescence microplate reader and photographed with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX51 with SPOT camera; total magnification ×200). (C) AcLDL binding to THP-1 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 30 minutes at 4°C. (D) AcLDL uptake in U937 macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (E) AcLDL uptake in human PBMC–derived macrophages. The cells were treated with protein S for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. Columns and bars denote the mean and SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls.

Binding assay was performed to determine whether the inhibitory effect of protein S on the uptake of Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL was due to the reduced Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL binding to THP-1 macrophages. As shown in Figure 1C, protein S treatment significantly reduced the binding of Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL to THP-1 macrophages (n = 3; P < .05).

To determine the inhibitory effect of protein S on other types of macrophages including U937 and human PBMCs isolated from human peripheral blood, both U937 cells and PBMCs were induced to macrophages in vitro. We observed that treatment with protein S significantly reduced the uptake of Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL by both U937- and human PBMC–derived macrophages (n = 3; P < .05; Figure 1D,E). These findings indicated that human protein S suppressed the SR-A function in macrophages derived from 2 human monocytic cell lines and human PBMCs.

To test the possible contamination of Gas6 in the human protein S preparation, we established a standard curve detecting human Gas6 protein concentrations using a highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The detection limit of ELISA was 0.03 ng/mL Gas6 (Figure S3A). However, Gas6 was not detected in 1 mg/mL protein S by ELISA. We further determined the effect of different concentrations of Gas6 on AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. We found that Gas6 at the concentration range of 10 to 20 ng/mL could inhibit AcLDL uptake (Figure S3B). However, the concentration range from 0.01 to 1 ng/mL Gas6 did not show any effects on AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. Thus, the possibility of the contamination of Gas6 in the human protein S preparation is ruled out in the current study.

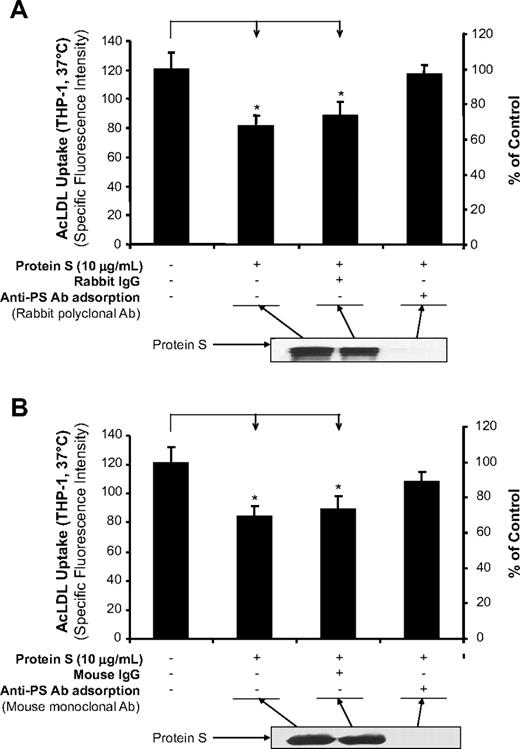

To determine whether protein S is specifically responsible for the inhibition of AcLDL uptake, we immunodepleted protein S from the reaction mixture and tested the supernatants for AcLDL uptake activity in THP-1 macrophages. The inhibitory effect of protein S on Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL uptake was almost completely reversed after the removal of protein S by rabbit polyclonal antibody (Figure 2A) and by mouse monoclonal antibody (Figure 2B) against human protein S. Immunoblot analysis indicated that human protein S was efficiently removed by immunodepletion from the reaction mixture.

Immunodepletion of protein S. (A) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. Protein S was immunodepleted by rabbit anti–protein S antibody for 2 hours at 4°C. The immune complexes and antibody were removed using protein G Sepharose for 1 hour at 4°C. The resultant supernatant fluid was used for the AcLDL uptake assay in THP-1 macrophages, and the degree of protein S depletion was monitored by immunoblotting using the same anti–protein S antibody. Normal rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. (B) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. Protein S was immunodepleted by monoclonal mouse anti–protein S antibody and protein G sepharose. Normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control. Representative results were from 3 experiments. Columns and bars denote the mean and SD. *P < .05 versus untreated controls.

Immunodepletion of protein S. (A) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. Protein S was immunodepleted by rabbit anti–protein S antibody for 2 hours at 4°C. The immune complexes and antibody were removed using protein G Sepharose for 1 hour at 4°C. The resultant supernatant fluid was used for the AcLDL uptake assay in THP-1 macrophages, and the degree of protein S depletion was monitored by immunoblotting using the same anti–protein S antibody. Normal rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. (B) AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages. Protein S was immunodepleted by monoclonal mouse anti–protein S antibody and protein G sepharose. Normal mouse IgG was used as a negative control. Representative results were from 3 experiments. Columns and bars denote the mean and SD. *P < .05 versus untreated controls.

To rule out the possibility of nonphysiological protein S aggregates in our experiments, we analyzed commercially available human protein S preparation using native PAGE and immunoblot compared with human plasma sample because it is well known that protein S normally exists in human plasma in both free monomer form and high-affinity complex form with C4BP.25 Protein S aggregates were not detected in purified protein S, whereas the human plasma sample showed 2 forms (protein S-C4BP complex and protein S monomer) (Figure S4A). In addition, human protein S (2.5 μg) was heated at 80°C for different time points and then subjected to native PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Monomer form of protein S was observed only in the nonheated sample, whereas both protein S aggregate and monomer were observed in the heated samples (Figure S4B). Thus, these data clearly demonstrate that human protein S used in the current study remains in its monomer form in the experimental conditions.

Human protein S reduces intracellular cholesteryl ester accumulation

We further examined the effects of protein S on cholesteryl ester accumulation in THP-1 macrophages. Treatment of macrophages with a physiological concentration of protein S (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours significantly reduced intracellular cholesteryl ester contents by nearly 70% compared with the controls (n = 3; P < .05; Figure 3A), whereas the free cholesterol contents had a very limited change after protein S treatment (Figure 3B). These results suggest that human protein S has an inhibitory effect on the macrophage-to-foam cell transformation in vitro.

Effects of human protein S on intracellular cholesterol accumulation in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were treated with 20 μg/mL protein S and 50 μg/mL AcLDL for 24 hours. The cellular cholesterol content was measured using a Wako Chemicals cholesterol assay kit. Values are mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. (A) Cholesterol ester content. (B) Free cholesterol content.

Effects of human protein S on intracellular cholesterol accumulation in THP-1 macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were treated with 20 μg/mL protein S and 50 μg/mL AcLDL for 24 hours. The cellular cholesterol content was measured using a Wako Chemicals cholesterol assay kit. Values are mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. (A) Cholesterol ester content. (B) Free cholesterol content.

Human protein S down-regulates SR-A expression in human macrophages

We investigated whether protein S treatment could down-regulate the expression of both SR-A mRNA and protein levels. Examination of SR-A mRNA levels by real-time quantitative PCR demonstrated that protein S treatment significantly reduced the levels of SR-A mRNA by nearly 50% in THP-1 macrophages, U937 macrophages, and human PBMC–derived macrophages (n = 3; P < .05; Figure 4A,C,E). Western blot assay also revealed that there was a marked increase in the expression of the SR-A protein in human macrophages (PMA treated) compared with human monocytes (PMA untreated). Treatment with protein S (10 μg/mL) clearly decreased the density of the SR-A protein band both in THP-1 macrophages and in U937 macrophages (Figure 4B,D). These data suggest that protein S negatively regulates the expression of SR-A. In contrast to SR-A mRNA, protein S treatment had no effect on VLDL receptor mRNA levels by real-time PCR analysis in THP-1 macrophages (data not shown). Interestingly, Gas6 (10-20 ng/mL), a homologue of protein S, was able to reduce SR-A expression in THP-1 macrophages (Figure S3C). However, both human protein S and Gas6 could not change SR-A expression in primary human aorta smooth muscle cells (Figure S5).

Inhibitory effects of human protein S on SR-A expression in human macrophages derived from THP-1 cells, U937 cells, and PBMCs. Macrophages were treated with protein S for 24 hours. (A) SR-A mRNA levels in THP-1 cells were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. (B) Protein levels of SR-A in THP-1 cells were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (C) SR-A mRNA levels in U937 cells were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. (D) Protein levels of SR-A in U937 cells were detected by Western blot analysis. (E) SR-A mRNA levels in PBMCs were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. Representative results from 3 experiments are shown. Values are mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. SR-A indicates macrophage scavenger receptor A.

Inhibitory effects of human protein S on SR-A expression in human macrophages derived from THP-1 cells, U937 cells, and PBMCs. Macrophages were treated with protein S for 24 hours. (A) SR-A mRNA levels in THP-1 cells were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. (B) Protein levels of SR-A in THP-1 cells were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (C) SR-A mRNA levels in U937 cells were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. (D) Protein levels of SR-A in U937 cells were detected by Western blot analysis. (E) SR-A mRNA levels in PBMCs were analyzed by real-time PCR quantification. Representative results from 3 experiments are shown. Values are mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. SR-A indicates macrophage scavenger receptor A.

Human protein S decreases SR-A expression at the transcriptional level

We calculated the half-life (t1/2) of SR-A mRNA in the THP-1 macrophages treated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin-D (Act-D). The SR-A mRNA levels were analyzed at different time points. The SR-A t1/2 was estimated to be 13 plus or minus 1 hour in both cells treated with and without protein S (Figure 5A). Thus, no difference was observed between protein S–treated and untreated THP-1 macrophages in the presence of Act-D, indicating that human protein S has no obvious effect on SR-A mRNA stability.

Effect of human protein S on the regulation of SR-A expression. (A) SR-A mRNA stability. THP-1 macrophages were treated with 5 μg/mL actinomycin D (Act-D) in the presence or absence of 20 μg/mL protein S for 16 hours. Total RNA was harvested at the indicated times and analyzed by real-time PCR using SR-A and 18S rRNA primers. Data are shown as the percentage of mRNA remaining in respect to cells before the addition of Act-D. Representative results from 3 experiments are shown. (B) SR-A promoter activity. THP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected by electroporation with SR-A gene promoter constructs (WT, PU.1 mutation, and AP-1 mutation) and pRL-SV40 plasmids as an internal control. After the transfection, the cells were treated with PMA (50 ng/mL) for 24 hours, followed by protein S (20 μg/mL) treatment for 24 hours. Dual-luciferase assay was performed. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. (C) PU.1-, AP-1–, and Ets-binding activities. Nuclear extracts were prepared. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed using biotin end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides including PU.1, AP-1, and Ets consensus sequences in the SR-A promoter. The transcription factor–probe mixtures were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane. The signal was detected with an EMSA kit (Panomics). Representative results were from 3 experiments. (i) PU.1 probe. (ii) AP-1 probe. (iii) Ets probe.

Effect of human protein S on the regulation of SR-A expression. (A) SR-A mRNA stability. THP-1 macrophages were treated with 5 μg/mL actinomycin D (Act-D) in the presence or absence of 20 μg/mL protein S for 16 hours. Total RNA was harvested at the indicated times and analyzed by real-time PCR using SR-A and 18S rRNA primers. Data are shown as the percentage of mRNA remaining in respect to cells before the addition of Act-D. Representative results from 3 experiments are shown. (B) SR-A promoter activity. THP-1 cells were transiently cotransfected by electroporation with SR-A gene promoter constructs (WT, PU.1 mutation, and AP-1 mutation) and pRL-SV40 plasmids as an internal control. After the transfection, the cells were treated with PMA (50 ng/mL) for 24 hours, followed by protein S (20 μg/mL) treatment for 24 hours. Dual-luciferase assay was performed. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls. (C) PU.1-, AP-1–, and Ets-binding activities. Nuclear extracts were prepared. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed using biotin end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides including PU.1, AP-1, and Ets consensus sequences in the SR-A promoter. The transcription factor–probe mixtures were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane. The signal was detected with an EMSA kit (Panomics). Representative results were from 3 experiments. (i) PU.1 probe. (ii) AP-1 probe. (iii) Ets probe.

To determine whether the decreased SR-A mRNA expression in response to protein S in THP-1 macrophages could result from the attenuation of SR-A promoter activity, assays for luciferase activity driven by SR-A gene promoter were performed. THP-1 cells were transiently transfected by electroporation with the SR-A promoter-luciferase reporter construct. Luciferase activity was measured in THP-1 macrophages treated with or without protein S (20 μg/mL). As shown in Figure 5B, treatment with protein S significantly reduced luciferase activities in THP-1 macrophages (n = 3; P < .05), indicating that protein S decreased SR-A expression at the transcription level.

To identify the transcription factors responsible for the protein S–induced suppression of SR-A promoter activity in THP-1 macrophages, we performed EMSA with double-stranded oligonucleotides for various nuclear transcription factors. We found that stimulation with protein S remarkably reduced the AP-1 and PU.1 binding to the consensus AP-1 and PU.1 elements in THP-1 macrophages, respectively, whereas it had no effect on Ets-binding activity (Figure 5C). In the nuclear extract samples, binding activity was completely inhibited by a 60-fold molar excess of unlabeled AP-1–, PU.1-, and Ets-binding site (Figure 5C), demonstrating that the binding activity was specific. Furthermore, the mutation of AP-1 cis-element significantly decreased SR-A promoter activity and abolished the effect of protein S on SR-A promoter inhibition, whereas the mutation of PU.1 cis-element did not show any significant effect on both SR-A promoter activity and protein S–induced SR-A promoter inhibition (Figure 5B). These luciferase activity results supported our EMSA data that AP-1 was the major transcription factor involved in protein S–induced SR-A down-regulation in macrophages. Therefore, protein S–induced suppression in the transcription of SR-A gene is primarily due to the reduction in activities of transcription factors that interact with AP-1 cis-elements.

Mer RTK mediates the functions of human protein S in THP-1 macrophages

Previous studies suggested that protein S and its structural homologue, Gas6, could interact with the Tyro3/Ax1 family of RTKs,15,16 which include Axl, Tyro3, and Mer, although detail interaction is not clear. To investigate potential receptors for human protein S activity in macrophages, we measured the mRNA expression of Axl, Tyro3, and Mer in THP-1 cells by real-time PCR. THP-1 monocytes expressed all 3 RTK at low levels, whereas PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages substantially increased Mer RTK mRNA expression, but not Axl and Tyro3 RTK. In fact, Mer RTK mRNA level was 4365-fold and 126-fold higher than Axl and Tyro3 in THP-1 macrophages, respectively (Figure 6A). The high level of Mer RTK mRNA in macrophages was also observed in both U937 macrophages and human PBMC–derived macrophages, whereas the Mer RTK mRNA level in primary human aorta smooth muscle cells was very low (Figure S6). High protein levels of Mer RTK in THP-1 macrophages were confirmed by Western blot and there were no changes of Mer protein levels with and without protein S treatment for 24 hours (Figure 6B). Axl and Tyro3 proteins were not detected in THP-1 macrophages (data not shown).

Role of Axl/Tyro3/Mer RTK in the activity of human protein S. (A) The mRNA levels of Axl, Tyro3, and Mer RTK in THP-1 monocytes and THP-1 macrophages were analyzed by real-time PCR. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. (B) Mer protein expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S for 24 hours. Protein levels of Mer were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (C) Ligand binding assay. Purified human protein S (10 nM) was mixed with 10 nM Mer/Fc fusion protein or tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB)/Fc as a negative control at 4°C for 2 hours, followed by incubation with protein A agarose beads for additional 1 hour. Bound proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–protein S antibody. Protein S input (20%). (D) Tyrosine phosphorylation assay. THP-1 macrophages were serum-starved for 6 hours prior to the human protein S treatment (20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with goat anti-Mer antibody, and immunoblotted with a phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody or anti-Mer. (E) Herbimycin A (a broad-spectrum RTK inhibitor) blocking. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S plus 20 ng/mL herbimycin A for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (F) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S plus receptor/Fc chimera (Axl/Fc, Tyr3/Fc, or Mer/Fc) for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (G) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on SR-A protein expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S with or without Mer/Fc chimera for 24 hours. The SR-A protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (H) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on SR-A mRNA expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S with or without Mer/Fc chimera for 24 hours. The SR-A mRNA levels were detected by real-time PCR. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. Data represent mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls; #P < .05 versus protein S–treated group.

Role of Axl/Tyro3/Mer RTK in the activity of human protein S. (A) The mRNA levels of Axl, Tyro3, and Mer RTK in THP-1 monocytes and THP-1 macrophages were analyzed by real-time PCR. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. (B) Mer protein expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S for 24 hours. Protein levels of Mer were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (C) Ligand binding assay. Purified human protein S (10 nM) was mixed with 10 nM Mer/Fc fusion protein or tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB)/Fc as a negative control at 4°C for 2 hours, followed by incubation with protein A agarose beads for additional 1 hour. Bound proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–protein S antibody. Protein S input (20%). (D) Tyrosine phosphorylation assay. THP-1 macrophages were serum-starved for 6 hours prior to the human protein S treatment (20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with goat anti-Mer antibody, and immunoblotted with a phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody or anti-Mer. (E) Herbimycin A (a broad-spectrum RTK inhibitor) blocking. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S plus 20 ng/mL herbimycin A for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (F) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S plus receptor/Fc chimera (Axl/Fc, Tyr3/Fc, or Mer/Fc) for 24 hours, followed by incubation with 5 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488–AcLDL in the presence or absence of 250 μg/mL AcLDL for 3 hours at 37°C. (G) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on SR-A protein expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S with or without Mer/Fc chimera for 24 hours. The SR-A protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (H) Mer/Fc chimera blocking the effects of protein S on SR-A mRNA expression. THP-1 macrophages were treated with protein S with or without Mer/Fc chimera for 24 hours. The SR-A mRNA levels were detected by real-time PCR. Results were normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. Data represent mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments. *P < .05 versus untreated controls; #P < .05 versus protein S–treated group.

The binding potential of protein S to Mer RTK was determined by coprecipitating protein S with chimeric protein Mer/Fc or TrkB/Fc (control), which contains the extracellular domain of Mer or TrkB fused to the Fc region of human immunoglobulin IgG1 heavy chain. The immunoblot analysis showed that Mer/Fc, but not TrKB/Fc, specifically coprecipitated protein S (Figure 6C).

To determine whether protein S could activate Mer RTK, the tyrosine phosphorylation of Mer RTK was assessed by immunoblotting with antiphosphorylation antibody after immunoprecipitating. We found that protein S could induce Mer phosphorylation (Figure 6D). As controls, we did the same procedures for the phosphorylation of Axl and Tyro3 RTK and there were no proteins or phosphorylation of Axl and Tyro3 detected under this condition (data not shown). In addition, we also observed that a broad-spectrum RTK inhibitor herbimycin A effectively blocked protein S–induced inhibition in AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages (Figure 6E).

To further determine the functional significance of Mer RTK on THP-1 macrophages for protein S activity, we used a recombinant human Mer/Fc chimeric protein to block the effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophage. Axl/Fc and Tyro3/Fc chimeric proteins were used as controls. As shown in Figure 6F, Mer/Fc, but not Axl/Fc and Tyro3/Fc, significantly blocked the effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake. Furthermore, the Mer/Fc chimeric protein also inhibited protein S–induced decrease in SR-A expression at both protein and mRNA levels (Figure 6G,H). These data demonstrate that protein S interacts with Mer RTK, which mediates the decrease in SR-A expression and AcLDL uptake in THP-1 macrophages.

Level of human protein S is increased in human atherosclerotic vessels

Since protein S could be synthesized by vascular cells or recruited by apoptotic cells,26 we therefore performed immunostaining to detect the expression of protein S in human arteries. Nonatherosclerotic vessels including human coronary artery, carotid artery, and aorta showed no or very limited protein S immunoreactivity. By contrast, atherosclerotic regions of these arteries showed a strong protein S immunoreactivity. The increased signal of protein S was located mainly in intima and media areas of atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 7A). In addition, preincubation of protein S antibody with soluble protein S fully abolished the protein-positive staining in the atherosclerotic vessel (Figure 7B), indicating the specificity of protein S immunoreactivity. Serial sections from atherosclerotic tissues were stained with anti–protein S antibody and anti–SR-A antibody, respectively. We found that the area with strong protein S immunoreactivity had almost no immunostaining of SR-A, whereas the area with positive SR-A immunostaining showed a very limited staining of protein S (Figure 7C), which may suggest the functional significance of regulation of SR-A expression by protein S in atherosclerotic tissues. In nonatherosclerotic vessels, however, there was no detectable SR-A immunoreactivity (data not shown), which is consistent with a previous study by Matsumoto et al.27 These results were observed in 3 atherosclerosis cases and 2 nonatherosclerosis cases. Non–immune rabbit IgG did not generate any signals in the atherosclerotic lesions (data not shown).

Protein S and SR-A immunoreactivity of human atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic arteries. Human aorta, and carotid and coronary arteries were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Immunostaining was performed using the antihuman protein S antibody (1:200), antihuman SR-A antibody (1:100), biotinylated secondary antibody, and avidin-biotin reaction using peroxidase enzyme. Brown color represents positive staining of protein S or SR-A. (A) Protein S immunoreactivity in human aorta, and carotid and coronary arteries. Nonimmune rabbit IgG was used as negative controls. (B) Soluble protein S blocked immunostaining with anti–protein S antibody in human aorta. Anti–protein S antibody was preincubated with soluble protein S before adding to the slides. (C) Localization of protein S and SR-A immunoreactivity in serial sections of human aorta and carotid artery (magnification ×400). (i) Protein S immunostaining (positive area) for an atherosclerotic region of human aorta. (ii) SR-A immunostaining (negative area) for an atherosclerotic region of human aorta. (iii) Protein S immunostaining (negative area) for an atherosclerotic region of human carotid artery. (iv) SR-A immunostaining (positive area) for an atherosclerotic region of human carotid artery. Red arrows indicate positive staining.

Protein S and SR-A immunoreactivity of human atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic arteries. Human aorta, and carotid and coronary arteries were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Immunostaining was performed using the antihuman protein S antibody (1:200), antihuman SR-A antibody (1:100), biotinylated secondary antibody, and avidin-biotin reaction using peroxidase enzyme. Brown color represents positive staining of protein S or SR-A. (A) Protein S immunoreactivity in human aorta, and carotid and coronary arteries. Nonimmune rabbit IgG was used as negative controls. (B) Soluble protein S blocked immunostaining with anti–protein S antibody in human aorta. Anti–protein S antibody was preincubated with soluble protein S before adding to the slides. (C) Localization of protein S and SR-A immunoreactivity in serial sections of human aorta and carotid artery (magnification ×400). (i) Protein S immunostaining (positive area) for an atherosclerotic region of human aorta. (ii) SR-A immunostaining (negative area) for an atherosclerotic region of human aorta. (iii) Protein S immunostaining (negative area) for an atherosclerotic region of human carotid artery. (iv) SR-A immunostaining (positive area) for an atherosclerotic region of human carotid artery. Red arrows indicate positive staining.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that physiological concentration of human protein S (20 μg/mL) significantly inhibits SR-A–mediated AcLDL uptake and SR-A expression in human monocyte–derived macrophages in vitro. We show that protein S is able to bind and activate Mer RTK, which is responsible for these activities of protein S. Level of protein S is dramatically increased in human atherosclerotic arteries.

Lipid-laden macrophage-derived foam cells are the predominant cell type in the formative stages of atherosclerosis. Foam cell formation through scavenger receptors is generally thought of as a protective mechanism during the initial stages of atherogenesis through their ability to remove potentially harmful lipids. However, the system frequently goes awry once macrophage pathways for metabolizing lipoprotein-derived cholesterol become overwhelmed.28 In addition, macrophages also play a critical role in the mediation and modulation of inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions. Our data have shown that the physiological concentration of protein S had significantly inhibitory effects on SR-A–mediated AcLDL binding and uptaking activities, and the intracellular cholesteryl ester accumulation in human monocyte–derived macrophages in vitro. Thus, the current observations suggest that human protein S may act as a negative regulator for foam cell formation through the inhibition of SR-A functions. Our findings that protein S activates macrophage Mer RTK also imply that protein S may attenuate apoptotic cell accumulation and plaque necrosis in atherosclerotic lesions through Mer RTK signaling since 2 most recent studies have shown that mutation of the phagocytic Mer RTK promotes the accumulation of apoptotic cells and the formation of necrotic plaques.29,30 However, overall contributions of protein S to the atherothrombotic disease formation need to be assessed in protein S deficiency or overexpression in mice with atherosclerosis-susceptible background. Developing such animal models is warranted in the field. We should also assess whether atherosclerotic plaque in protein S/apoE double knockout mice has an increased incidence of intraplaque hemorrhage or plaque rupture since protein S is such an important anticoagulation factor and an inflammation regulator.

Murao et al31 and Ming Cao et al32 reported that Gas6, the structural homologue of protein S, induced SR-A expression in ISS10 cell line (SV40-transformed human aortic smooth muscle cells), which expressed Axl. However, Gas6 did not induce the expression of SR-A in primary human aortic smooth muscle cells, which did not express Axl. We tested the effects of both protein S and Gas6 in primary human aortic smooth muscle cells and the results were in agreement with the other authors' findings that both protein S and Gas6 did not induce the expression of SR-A in primary human aorta smooth muscle cells, which did not express Axl. The contradictory effects of protein S in macrophages and Gas6 in ISS10 cells may reflect the fact that the basal levels of scavenger receptor expression in these 2 cell types are markedly different. Macrophages constitutively express SR-A, whereas vascular smooth muscle cells express little or no scavenger receptor in the absence of stimulation.33 The mechanism for the divergent effects of these proteins in these 2 types of cells is not fully understood.

The positive transcriptional control of SR-A gene in monocytes and macrophages was determined primarily by PU.1 and a composite AP-1/Est motif. The AP-1/Ets motif was found to be critical for the transcriptional response of the SR-A gene to PMA.24 In agreement with previous studies, the mutation of AP-1 motif in the current study reduced the SR-A promoter's 3-fold response to PMA. Mutation of AP-1 cis-element also significantly abolished the inhibitory effect of protein S on SR-A transcription. Furthermore, EMSA in the current study demonstrated that protein S decreased the DNA-binding activity of AP-1. These results indicate that AP-1 is the major transcription factor involved in protein S–induced SR-A down-regulation in macrophages. However, the upstream signaling pathway mediating this transcriptional inhibition remains unknown at this time. Our current results show that human protein S can bind and induce Mer receptor phosphorylation in THP-1 macrophages. The effects of protein S on AcLDL uptake could be effectively reversed by Mer/Fc or RTK inhibitor herbimycin A. Thus, our study clearly demonstrates that Mer RTK is the receptor mediating the signal transduction pathways related to the activities of human protein S in human macrophages.

The plasma concentration of Gas6 is 13 to 23 ng/mL.34 Since Gas6 shows 43% amino acid sequence identity with human protein S,16 protein S isolated from plasma could be contaminated by Gas6. However, the current study excludes the possibility of Gas6 contamination in the protein S preparation. Protein S and Gas6 have a similar domain organization and share some activities, although they also have many differences in functions. For example, human protein S plays a critical role in homeostasis and thrombosis, whereas human Gas6 appears to be redundant for baseline homeostasis. Human Gas6 is a potent ligand for Axl/Tyro3/Mer RTKs, whereas human protein S has been documented as a weak ligand for human Sky RTK, but has interspecies activity against mouse or rat Sky. Our current study proves that human protein S is a ligand for human Mer RTK. In addition, our findings show that human Gas6 is much more potent than human protein S for the inhibition of the uptake of modified LDL by human macrophage cells. Only 20 ng/mL Gas6 is required for the function instead of 20 μg/mL protein S (1000-fold difference), suggesting that both human protein S and Gas6 could inhibit macrophages uptaking AcLDL at their physiological concentrations. These findings imply that Gas6 and protein S may compensate each other in regulating macrophage functions through Mer receptor especially when one of them is deficient. The overlap of their functions may help to explain some observations. For example, there is no clear correlation between the protein S level and the risk of atherosclerosis in patients; and the absence of Gas6 has no obvious effect on atherosclerosis extent in mice.35 The failure to observe more atherosclerosis in Gas6-deficient mice also suggests that protein S and Gas6 double knockout mice may be needed for determining their functions in vivo.

Our immunohistochemistry results show that protein S level is dramatically increased in atherosclerotic vessels compared with nonatherosclerotic vessels; and SR-A is not localized to the areas with strong protein S immunoreactivity in atherosclerotic vessels, suggesting that protein S may regulate SR-A expression in human vessels. The high level of protein S in the atherosclerotic lesion may be produced from local vascular cells or recruited by apoptotic cells from the circulation.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that human protein S is a modulator for macrophage functions in uptaking of modified lipoproteins, which may regulate atherogenesis and atherothrombosis process. These findings will lead us to explore novel mechanisms regarding atherogenesis and to seek new therapeutic strategies to treat patients with atherothrombosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Christopher K. Glass (University of California, San Diego) for his gift of SR-A promoter fragment.

This work was partially supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) (Q.Y.: DE15543 and AT003094; and C.C.: EB-002436, and HL083471) and by the Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (Houston, TX).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: All authors made contributions to the current study: D.L. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; X.W. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; M.L., P.H.L., and Q.Y. designed research and analyzed data; and C.C. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Changyi (Johnny) Chen, Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery (MARB413), Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Mail stop: BCM390, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: jchen@bcm.tmc.edu.