Selectins on activated vascular endothelium mediate inflammation by binding to complementary carbohydrates on circulating neutrophils. The human neutrophil receptor for E-selectin has not been established. We report here that sialylated glycosphingolipids with 5 N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc, Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3) repeats and 2 to 3 fucose residues are major functional E-selectin receptors on human neutrophils. Glycolipids were extracted from 1010 normal peripheral blood human neutrophils. Individual glycolipid species were resolved by chromatography, adsorbed as model membrane monolayers and selectin-mediated cell tethering and rolling under fluid shear was quantified as a function of glycolipid density. E-selectin–expressing cells tethered and rolled on selected glycolipids, whereas P-selectin–expressing cells failed to interact. Quantitatively minor terminally sialylated glycosphingolipids with 5 to 6 LacNAc repeats and 2 to 3 fucose residues were highly potent E-selectin receptors, constituting more than 60% of the E-selectin–binding activity in the extract. These glycolipids are expressed on human blood neutrophils at densities exceeding those required to support E-selectin–mediated tethering and rolling. Blocking glycosphingolipid biosynthesis in cultured human neutrophils diminished E-selectin, but not P-selectin, adhesion. The data support the conclusion that on human neutrophils the glycosphingolipid NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (and closely related structures) are functional E-selectin receptors.

Introduction

Multiple mechanisms ensure that granulocytes efficiently move into tissues when and where needed.1 Activation of the blood vessel endothelium results in circulating granulocytes tethering and rolling, stopping, flattening, and squeezing into the surrounding tissue. A 3-step model describes leukocyte extravasation2 : (1) E- and P-selectin on activated endothelia bind to glycans on leukocytes, initiating tethering and rolling under the shear stress of blood flow (L-selectin on some leukocytes contributes to this process). (2) Upon tethering, leukocytes are exposed to chemoattractants (eg, chemokines) generated by activated endothelium and tissue-resident cells, resulting in integrin mobilization. (3) Strong cell adhesion is mediated by leukocyte integrin binding to immunoglobulin superfamily proteins on the endothelium. Each step is required for recruitment of leukocytes; blocking any one diminishes inflammation. Despite exceptions,3 this scheme is broadly applicable

Each selectin (E-, L-, and P-)4 has a carbohydrate recognition domain that mediates binding to specific glycans on apposing cells. They have remarkably similar protein folds and carbohydrate binding residues,5 leading to overlap in the glycans to which they bind. Nevertheless, each selectin has distinct receptors to which it binds with high affinity.

Selectins bind to the sialyl Lewisx (SLex) determinant “NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAc.”6,,–9 However, SLex, per se, does not constitute an effective selectin receptor.10,–12 Instead, SLex and related sialylated, fucosylated glycans are components of more extensive binding determinants. Designation of a glycoconjugate as a functional selectin receptor requires that (1) it is expressed on the proper cells at the proper time; (2) its removal or blockade diminishes function; and (3) its binding selectivity and affinity are consistent with its function.10 Furthermore, its biochemical properties must be consistent with those demonstrated for endogenous selectin receptors. Because the same selectin binds different receptors depending on the target cell type and animal species, it is essential to apply these criteria to the specific cells and species involved.

Receptors for P-selectin and L-selectin that fit these criteria have been identified. P-selectin binds to P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1); the receptor sequence contains an O-linked SLex glycan on a threonine residue near a trio of sulfated tyrosines.12 High-affinity binding requires both SLex and tyrosine sulfation. L-selectin binds with high affinity to glycoprotein receptors (eg, GlyCAM-1) that carry O-linked SLex with a sulfate on the 6-hydroxyl of the SLex GlcNAc residue.13 Each selectin binds to SLex, yet each uses additional strategies to enhance receptor selectivity and affinity.

Human neutrophil receptor(s) for E-selectin have not been confirmed. One reason is that E-selectin receptors in mice differ from those in humans.14 Treatment of mouse neutrophils with powerful proteases eliminated both P-selectin and E-selectin binding, whereas treatment of human neutrophils with the same proteases eliminated only P-selectin binding, leaving most E-selectin binding intact.14,,–17 Gene- and RNA-targeted depletion identified glycoprotein receptors for E-selectin in mice.18 However, if humans express different E-selectin receptors than mice, mouse genetics may not reveal their nature.

Protease insensitivity implies that human neutrophil E-selectin receptors are glycolipids or protease-resistant glycoproteins. Prior data implicate glycolipids. The first study to isolate endogenous E-selectin–binding molecules from a human source (myelogenous leukemia cells) revealed a glycosphingolipid (GSL) with the “VIM 2” terminal structure (Figure 1 inset).19 Related sialylated fucosylated poly-N-acetyllactosaminyl glycolipids, dubbed myeloglycans, were later isolated from the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60,20 and shown to support E-selectin adhesion.21 These E-selectin–binding structures are terminally monosialylated glycosphingolipids with LacNAc (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3) repeats and one or more fucose residues, with variations occurring in the number of repeats and the number and position of the fucose residues.

In the current study, GSLs extracted from approximately 1010 human leukocytes were resolved chromatographically and tested for their ability to support selectin-mediated tethering and rolling as a function of glycolipid density. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) and total ion mapping mass spectroscopy (MS) identified key selectin-binding molecular species. Finally, biosynthetic inhibitors established that GSLs are E-selectin receptors on human blood neutrophils. Together, the data designate a narrow set of quantitatively minor sialylated fucosylated GSLs as endogenous receptors for E-selectin on human neutrophils.

Methods

Venipuncture from volunteers (to prepare fresh human neutrophils) was approved by the Johns Hopkins University's institutional review board and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Extraction and purification of human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids

Leukapheresis packs were divided into 10-mL aliquots in 50-mL tubes, hypotonically shocked by addition of 18 mL cold distilled water per tube, mixed gently for 30 seconds, and then 2 mL of 1.5 M Pipes buffer (pH 7.2) was added. Cells were collected by centrifugation, supernatants were decanted, and hypotonic shock was repeated. Leukocytes were collected by centrifugation, washed with isotonic Pipes buffer, and resuspended. An aliquot was counted with erythrosin B to determine total cell count and viability (> 95%), Alcian blue was used to determine basophil counts, and Diff-Quik (American Scientific Products, McGraw Park, IL), for differential cell counts. Leukocyte percentages were similar to whole blood: 75% neutrophils, 15% lymphocytes, 8% monocytes, and 1% to 2% each basophils and eosinophils.

Leukocytes (∼ 1010 cells) were treated with organic solvents to precipitate proteins and solubilize glycosphingolipids.22 Cell pellets were adjusted to approximately 5 × 108/mL with ice-cold water (W), then methanol (M) was added to give a M/W ratio of 8:3. The suspension was mixed vigorously and brought to ambient temperature, and chloroform (C) was added to give a C/M/W ratio of 4:8:3. The tightly capped suspension was stirred for 2 hours at ambient temperature, and clarified by centrifugation. The pellet was reextracted with C/M/W (4:8:3), and the resulting clarified extracts were combined. Water was added to bring the C/M/W ratio to 4:8:5.6, resulting in 2 phases. The suspension was mixed vigorously and centrifuged to separate the phases. The upper phase (polar lipids) was removed, and the lower phase dried, resuspended in C/M/W (4:8:3), and repartitioned by addition of water, and the upper phase from the repartition was combined with the original upper phase. The combined upper phases were evaporated, resuspended in C/M/W (2:43:55), and applied to tC18 SepPak Plus cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA) connected in series (one cartridge for each 3 × 109 cells). The cartridges were washed with C/M/W (2:43:55) and M/W (1:1) then GSLs were eluted with methanol, followed by M/C (1:1). Fractions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) stained with resorcinol reagent to detect lipid-bound sialic acid and molybdate to detect contaminating phospholipids.23 The procedure resulted in recovery of 450 nmol lipid-bound sialic acid per 1010 leukocytes.

Contaminating phospholipids were removed by solvent partition24 or phospholipase digestion.25 For solvent partition, polar lipid extract was evaporated and redissolved in n-butanol–diisopropylether (4:6) (70 mL/1010 leukocytes extracted). Half the volume of aqueous NaCl (50 mM) was added and the 2-phase system mixed vigorously. The upper phase was discarded and the aqueous lower phase reextracted 3 times with the same solvent mixture, dried, resuspended in C/M/W (2:43:55), and resubjected to tC18 SepPak chromatography. Alternatively, the ganglioside fraction was evaporated to dryness and resuspended in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4, 250 μL/1010 leukocytes extracted). Phospholipase C (Bacillus cereus; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added (0.6 mU/mL) and the reaction incubated at 37°C for 12 hours, with an equivalent amount of enzyme added every 3 hours. At the end of the reaction, chloroform and methanol were added to achieve a C/M/W ratio of 4:8:3, and the sample was centrifuged to remove precipitated protein. Water was added to the supernatant to achieve a C/M/W ratio of 4:8:5.6, and after mixing and separation of phases by centrifugation the resulting upper phase was subjected to tC18 SepPak chromatography.

Monosialo GSLs were isolated by DEAE-Sepharose ion exchange chromatography.22 The glycosphingolipid fraction was evaporated to dryness, redissolved in C/M/W (30:60:8), and loaded onto DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), using 10 mL resin per 1010 leukocytes extracted. After washing with the same solvent mixture, monosialylated species were eluted with 15 column volumes of 15 mM ammonium acetate in methanol. The eluate was evaporated to dryness, redissolved in C/M/W (2:43:55), and subjected to tC18 SepPak chromatography.

Resolution of human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids

Separation of monosialo GSLs was achieved by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).26 Purified leukocyte monosialo GSLs (up to 220 nmol) were dissolved in water and injected onto a 250 × 4.6-mm column packed with 5-μm diameter LiChrosorb NH2 beads (Alltech, Deerfield, IL). Glycosphingolipids were eluted using an 80-minute acetonitrile-aqueous sodium phosphate gradient as described.26 For subsequent cell adhesion assays and total ion mapping MS, volatile solvents were used: solvent A, acetonitrile–10 mM NH4HCO3 (9:1); solvent B, acetonitrile–100 mM aqueous NH4HCO3 (1:1). A 1-mL/min gradient was used consisting of 7 minutes of solvent A, a 60-minute linear gradient to solvents A/B (60:40), then a 30-minute linear gradient to solvents A/B (15:85). A subsequent preparative column (300 × 10 mm, 500 nmol loaded) used the same volatile solvents and a 2-mL/min gradient consisting of 10 minutes of solvent A, a 30-minute linear gradient to solvents A/B (70:30), 20 minutes of isocratic solvents A/B (70:30), then a 100-minute gradient to 100% solvent B. All runs were monitored using an in-line UV detector (215 nm).

The concentrations of eluted gangliosides were estimated by UV absorbance. To confirm the relationship between A215 and sialic acid content, selected fractions were subjected to hydrolysis and quantitative sialic acid analysis. A good correlation between measured sialic acid and that calculated based on A215 was obtained.

Analytical methods

Sialic acid was measured by acid release followed by Dionex separation (strong anion exchange HPLC; Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) and pulsed amperometric detection.27 Samples were evaporated to dryness in Eppendorf tubes, hydrolyzed in 100 mM HCl, 250 mM NaCl for 3 hours at 80°C, then injected onto the Dionex system. Neutral sugars were analyzed by hydrolysis in 2 M trifluoroacetic acid in sealed glass tubes at 100°C for 3 hours followed by evaporation, redissolving in water, and analysis using the same system.28,29 TLC was performed on silica gel plates using C/M/0.25% aqueous KCl (60:35:8) as developing solvent.23 Gangliosides were detected using resorcinol/HCl reagent and phospholipids, using molybdate.23

MALDI mass spectroscopy

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed on underivatized samples using a Kratos (Manchester, United Kingdom) AXIMA-CFR MALDI-TOF high-performance mass spectrometer equipped with a pulsed nitrogen laser (337 nm), using 20-kV extraction voltage and time-delayed extraction. Saturated 6-aza-2-thiothymine in 100% methanol was used as the matrix. The sample was prepared for MALDI analysis by depositing 0.3 μL matrix followed by 0.3 μL analyte (100 pmol/μL in methanol), which was then dried at room temperature. The spectrum was acquired in negative ion linear mode and consisted of an average of 100 laser shots. For HPLC fractions, MALDI was performed using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) Voyager DE-STR MALDI-TOF with the same matrix but using methanol-water (1:1) as solvent.

Total ion mapping mass spectroscopy

Nanospray ionization mass spectrometry was performed on enzymatically released then permethylated GSL glycans. GSLs were dried from solvent and resuspended in 20 μL 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, containing 0.1% sodium cholate. Ceramide glycanase30 was added (1 μL, 0.1 mU; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). After 18 hours at 37°C in a Teflon-sealed glass tube, oligosaccharides were separated from ceramide by phase partition. Chloroform-methanol (2:1, 100 μL) was added, the mixture agitated and centrifuged, and the upper phase collected. Reextraction of the lower phase was repeated thrice with theoretic upper phase. Combined upper phases were dried by vacuum centrifugation, resuspended in 250 μL of 5% acetic acid and loaded onto a C18 cartridge (100 mg; J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) previously washed with 100% acetonitrile and pre-equilibrated with 5% acetic acid. Oligosaccharides were recovered by collecting the column run-through and 3 additional column volumes of 5% acetic acid wash. The combined eluates were evaporated to dryness.

Released oligosaccharides were permethylated,31 dissolved in 1 mM NaOH in methanol-water (1:1), and infused into a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using a nanoelectrospray source at a syringe flow rate of 0.40 μL/min. The capillary temperature was set to 210°C, and MS analysis was performed in positive ion mode. For fragmentation by collision-induced dissociation in MS/MS and sequential production (MSn) modes, a normalized collision energy of 20% to 30% was used. Detection and relative quantification of the prevalence of individual glycans was accomplished using the total ion mapping functionality of the Finnigan Xcalibur software package version 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described.32 Briefly, the m/z range from 500 to 2000 was automatically scanned in successive 2.8 mass unit windows with a window-to-window overlap of 2 mass units, which allowed the naturally occurring isotopes of glycans to be summed into a single response, increasing detection sensitivity. The 2 mass unit overlap ensured that glycans would be sampled in a representative fashion. Most permethylated oligosaccharides were identified as singly, doubly, and triply charged species. Peaks for all charge states were summed for quantification. The positions of fucose branches were identified by analyzing the fragmentation patterns of permethylated glycans by MSn (up to MS5 ).

Selectin-mediated cell tethering and rolling under fluid shear

E-selectin– and P-selectin–mediated tethering and rolling of cells on glycolipid model membrane monolayers was determined as described previously.33 Human leukocyte glycosphingolipids were dissolved in ethanol-water (1:1) containing 25 μM phosphatidylcholine and 25 μM cholesterol. Then, 2 μL of the solution (5 fmol-20 pmol glycolipid) were pipetted in a 5-mm circle in the center of a butanol- and ethanol-washed 35-mm diameter polystyrene culture dish and allowed to evaporate. The plates were washed with water then blocked with 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes at 37°C. A wide variety of glycosphingolipids are stably adsorbed at an efficiency of approximately 40% using this protocol.34

Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts (CHO cells) stably transfected with full-length E-selectin (CHO-E) or a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked extracellular domain of P-selectin (CHO-P), kind gifts of Dr Christine Martens (Affymax, Palo Alto, CA), were cultured as described.33 Cells were removed from culture dishes nonenzymatically (0.53 mM EDTA in divalent cation-free PBS), collected by centrifugation, and resuspended at 106 cells/mL in PBS containing 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. Cells were kept on ice, then warmed to 37°C for 5 minutes immediately before use. Cell suspensions were perfused over glycolipid-adsorbed areas at 1 dyne/cm2 using a parallel plate flow chamber and a videomicroscopy/digital image processing system,35 and the number of tethered cells (interacting ≥ 2 seconds) was quantified over a 5-minute observation period. Rolling velocities were determined as the displacement of the centroid of the cell over a 5-second interval.36 The specificity of E-selectin–mediated tethering and rolling was demonstrated by the use of a function-blocking monoclonal antibody against E-selectin (data not shown).

Tethering of human neutrophils to E- and P-selectin was determined as described previously.35 Freshly prepared human neutrophils37 were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with or without phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 1.6 μM). Cells were washed and resuspended at 106/mL in PBS and perfused over monolayers of CHO-E or CHO-P cells in 35-mm dishes in the parallel plate flow chamber at a wall shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2. The number of tethered cells (interacting ≥ 2 seconds) was determined over a 5-minute period.

Human neutrophil culture and selectin-mediated static cell adhesion

Human neutrophils were cultured for 48 hours, with inhibitors of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis added during the final 24 hours. Because cultured neutrophils assumed morphologies that hampered analysis of tethering/rolling under fluid shear, static adhesion to purified E- and P-selectin was used as a functional alternative. Neutrophils were isolated from healthy volunteers38 and maintained in culture in the presence of 1 ng/mL granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).39 After 24 hours, the following glycosphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitors (or controls) were added: d,l-threo-1-phenyl-2-hexadecanoylamino-3-pyrrolidino-1-propanol·HCl (P4, 5 μM), d,l-threo-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol·HCl (t-PDMP, 50 μM), or its inactive erythro stereoisomer (e-PDMP, 50 μM), from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA), or N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin (NB-DGJ, 50 μM) from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON). After an additional 24 hours, the cells were incubated with sodium [51Cr]chromate (New Life Sciences Products, Boston, MA), and adhesion to purified recombinant E-selectin and P-selectin (R&D Systems) was determined as described previously.16,17 Neutrophil purity and fresh cell viability were more than 97%. Post culture viability (> 60%) was equivalent for different treatments.

Results

Isolation and structural analyses of glycosphingolipids from human leukocytes

Human leukocytes were purified from leukapheresis packs, extracted with solvents, and partitioned to isolate polar lipids. These were treated to deplete phospholipids, then resolved into monosialoganglioside and disialoganglioside species by anion exchange chromatography. Selectin-binding activity of the fractions was initially screened by static adhesion.33 The monosialo fraction (93% of the sialylated glycolipids) contained all of the E-selectin–binding activity. Leukocyte GSLs did not support P-selectin binding. E-selectin–dependent cell adhesion to leukocyte glycolipids was reversed by sialidase, was resistant to trypsin treatment of the adsorbed surface, and was calcium dependent.

TLC of the monosialo GSL fraction (not shown) revealed species that migrated as GM3 and a ladder of more complex GSLs.40 Carbohydrate compositional analyses revealed (ratios in parentheses): sialic acid (1.0), glucose (1.1), galactose (2.2), N-acetylglucosamine (0.8), and fucose (0.1). N-acetylgalactosamine and mannose were not detected. The ratios are consistent with a mixture of GM3 and poly-N-acetyllactosamine (poly-LacNAc) structures, a small percentage of which are fucosylated.40 Monosialo GSLs were abundant on leukocytes (2.4 × 107 molecules/cell), consistent with prior reports.41

MALDI-TOF MS allowed structural assignments based on literature precedent,20,40,42 which were later confirmed by MSn. Although MALDI-TOF MS is not strictly quantitative, the magnitude of the mass peaks correlated well with the abundance of GSLs resolved by HPLC (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

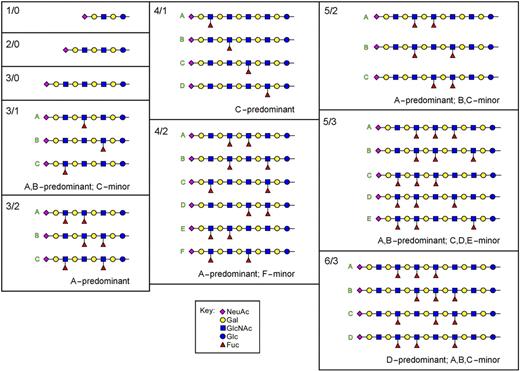

Thirty-two human leukocyte monosialo GSLs masses were identified (Figure 1; Table S1) corresponding to 16 glycan compositions with multiple masses due to variations in the ceramide structure. The results are consistent with structural assignments as GM3 (42%) and sialylated poly-LacNAc GSLs (58%) with up to 6 LacNAc repeats. Whereas fucose was absent from GM3 and GSLs with 1 or 2 LacNAc repeats, more than 50% of the GSLs with 3 LacNAc repeats had 1 to 2 fucose residues, and nearly all structures with 4 to 6 LacNAc repeats were fucosylated. Fucosylation increased with glycan length; more than 94% of structures with 5 LacNAc repeats carried 2 to 3 fucose residues, and more than 78% of those with 6 LacNAc repeats carried 3 to 4 fucose residues. These data imply that fucosyltransferase(s) preferentially act on GSLs with at least 3 LacNAc repeats as acceptors, with enhanced activity on longer poly-LacNAc structures (“Discussion”).43

MALDI-TOF MS of purified human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids. The monosialo GSL fraction from human leukocytes was subjected to MALDI-TOF MS. Peaks corresponding to masses of glycosphingolipids 110 mass units separated, reflecting the presence of the same glycan species bearing either C16:0 or C24:1 fatty acid amides, are indicated. The proposed structures are abbreviated as n/m where n is the number of LacNAc repeats and m the number of fucoses in the general structure NeuAcα2-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)0-1GlcNAcβ1-3]nGalβ1-4GlcβCer. The inset structure, 3/1, was isolated from human leukemia cells and contains 3 LacNAc repeats (one of which is fucosylated) and the VIM-2 structure19 (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry [IUPAC, Research Triangle Park, NC] designation: VIII3NeuAcV3Fuc-nLc8Cer).

MALDI-TOF MS of purified human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids. The monosialo GSL fraction from human leukocytes was subjected to MALDI-TOF MS. Peaks corresponding to masses of glycosphingolipids 110 mass units separated, reflecting the presence of the same glycan species bearing either C16:0 or C24:1 fatty acid amides, are indicated. The proposed structures are abbreviated as n/m where n is the number of LacNAc repeats and m the number of fucoses in the general structure NeuAcα2-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)0-1GlcNAcβ1-3]nGalβ1-4GlcβCer. The inset structure, 3/1, was isolated from human leukemia cells and contains 3 LacNAc repeats (one of which is fucosylated) and the VIM-2 structure19 (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry [IUPAC, Research Triangle Park, NC] designation: VIII3NeuAcV3Fuc-nLc8Cer).

Total ion mapping MSn of released permethylated glycans was consistent with the structure NeuAcα2-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)0-1-GlcNAcβ1-3]nGalβ1-4Glc and identified the positions of the fucose residues on the poly-LacNAc backbone (Figure 2; Figure S2). Linkage position and anomeric configurations were assigned based on published nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses of similar structures.20,42,45 Most fucosylated species lacked a fucose on the GlcNAc residue closest to the nonreducing terminus (eg, lacked the SLex structure), instead carrying fucose(s) on the second GlcNAc from the nonreducing terminus (VIM-2 structure; Figure 1 inset) and/or on GlcNAc residues further removed from the nonreducing terminus.

Structures of LacNAc and poly-LacNAc glycosphingolipid glycans from human leukocytes. The glycans of monosialo GSLs from human neutrophils were enzymatically released using ceramide glycanase, permethylated, and then subjected to total ion mapping MS and MSn. The structures of the most abundant 99% of species in the sample are shown in symbol format.44 Structure abbreviations (n/m) are defined in Figure 1 legend.

Structures of LacNAc and poly-LacNAc glycosphingolipid glycans from human leukocytes. The glycans of monosialo GSLs from human neutrophils were enzymatically released using ceramide glycanase, permethylated, and then subjected to total ion mapping MS and MSn. The structures of the most abundant 99% of species in the sample are shown in symbol format.44 Structure abbreviations (n/m) are defined in Figure 1 legend.

Structure-function studies on human leukocyte glycosphingolipids

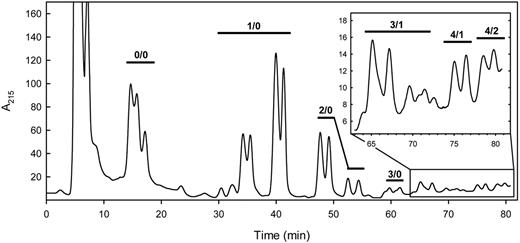

To determine the potency of each human leukocyte GSL to support selectin-mediated cell tethering and rolling, GSL species were first resolved by HPLC and quantified by inline UV absorbance. Resolution using a normal phase LiChrosorb NH2 column26 proved highly effective (Figure 3). Each fraction was analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS, allowing assignment of LacNAc repeats and fucose residues to each peak. Quantitative sialic acid analysis on selected fractions confirmed that the A215 accurately reflected the relative monosialo GSL concentration (data not shown), and the areas under the HPLC peaks correlated well with the magnitude of the MALDI-TOF MS abundance of the same species (Figure S1). Peaks were resolved based on both glycan and ceramide structures. Fucosylated species were quantitatively minor, representing approximately 10% of the monosialo GSLs (∼ 2.4 × 106 molecules/cell; ∼ 5300 molecules/μm2), with an average of 1.6 fucose residues/fucosylated species. Nonfucosylated species did not support selectin interactions (data not shown); subsequent functional studies focused on fucosylated species only.

HPLC of human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids. The purified monosialo GSLs from human leukocytes were resolved on a LiChrosorb NH2 HPLC column using an acetonitrile/aqueous sodium phosphate gradient as eluent.26 UV absorbance at 215 nm is proportional to the monosialo GSL concentration in the identified peaks. Species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram, with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend.

HPLC of human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids. The purified monosialo GSLs from human leukocytes were resolved on a LiChrosorb NH2 HPLC column using an acetonitrile/aqueous sodium phosphate gradient as eluent.26 UV absorbance at 215 nm is proportional to the monosialo GSL concentration in the identified peaks. Species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram, with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend.

HPLC using volatile salt (ammonium bicarbonate) was used to resolve the minor fucosylated species in a form amenable both to MS and quantitative analysis of selectin receptor activity. Although resolution was somewhat diminished (compared with that using sodium phosphate), sufficient separation was obtained to allow quantitative assignment of functional activity to distinct structures.

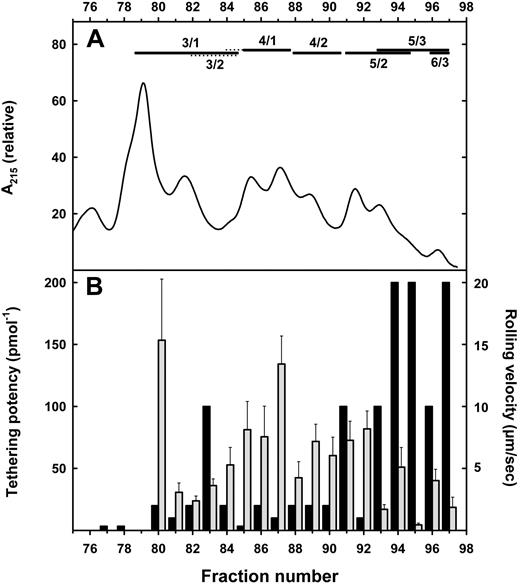

Aliquots of each HPLC fraction containing 0.005 to 20 pmol GSL were adsorbed as 5-mm diameter phospholipid/cholesterol/GSL membrane monolayers at the center of 35-mm Petri dishes. The ability of each fraction to support tethering and rolling of cells expressing E-selectin and P-selectin was determined using a parallel plate flow chamber.33 Cells expressing P-selectin did not tether or roll on any GSL at any density. In contrast, fucosylated sialylated leukocyte GSLs supported tethering and rolling of cells expressing E-selectin (Figure 4).

E-selectin–mediated cell tethering and rolling by resolved human leukocyte gangliosides. (A) Ganglioside resolution. Purified monosialoglycosphingolipids from human granulocytes were resolved on a LiChrosorb NH2 HPLC column using an acetonitrile/aqueous ammonium bicarbonate gradient as eluent. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown (compare with Figure 3; prior fractions did not support E-selectin tethering). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram (dotted lines indicate minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. (B) Tethering (■): Aliquots of each fraction containing from 5 fmol to 20 pmol were adsorbed as a lipid monolayer on Petri dishes in a discrete 5-mm diameter circular area. CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were perfused over the adsorbed lipid at 1 dyne/cm2 for a 5-minute period, during which tethered cells were quantified. The minimal ganglioside concentration resulting in at least 100 tethers/mm2 was determined. Potency is expressed as the inverse of the minimal effective concentration. Rolling ( ): Aliquots containing 100 to 300 fmol GSL were adsorbed and rolling velocities (μm/s) of CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were determined as the displacement of the centroid of the cell over a 5-second interval. The means plus or minus SEM of 6 to 34 cells are shown.

): Aliquots containing 100 to 300 fmol GSL were adsorbed and rolling velocities (μm/s) of CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were determined as the displacement of the centroid of the cell over a 5-second interval. The means plus or minus SEM of 6 to 34 cells are shown.

E-selectin–mediated cell tethering and rolling by resolved human leukocyte gangliosides. (A) Ganglioside resolution. Purified monosialoglycosphingolipids from human granulocytes were resolved on a LiChrosorb NH2 HPLC column using an acetonitrile/aqueous ammonium bicarbonate gradient as eluent. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown (compare with Figure 3; prior fractions did not support E-selectin tethering). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram (dotted lines indicate minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. (B) Tethering (■): Aliquots of each fraction containing from 5 fmol to 20 pmol were adsorbed as a lipid monolayer on Petri dishes in a discrete 5-mm diameter circular area. CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were perfused over the adsorbed lipid at 1 dyne/cm2 for a 5-minute period, during which tethered cells were quantified. The minimal ganglioside concentration resulting in at least 100 tethers/mm2 was determined. Potency is expressed as the inverse of the minimal effective concentration. Rolling ( ): Aliquots containing 100 to 300 fmol GSL were adsorbed and rolling velocities (μm/s) of CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were determined as the displacement of the centroid of the cell over a 5-second interval. The means plus or minus SEM of 6 to 34 cells are shown.

): Aliquots containing 100 to 300 fmol GSL were adsorbed and rolling velocities (μm/s) of CHO cells stably expressing E-selectin were determined as the displacement of the centroid of the cell over a 5-second interval. The means plus or minus SEM of 6 to 34 cells are shown.

Low to moderate E-selectin tethering activity was detected in fractions having monofucosylated and difucosylated glycosphingolipids with 3 to 4 LacNAc repeats. By comparison, the most potent fractions were those with 5 to 6 LacNAc repeats and 2 to 3 fucose residues. Several fractions supported avid E-selectin–mediated tethering when adsorbed at concentrations as low as 5 fmol per 5-mm diameter area. Based on a 40% adsorption efficiency,34 this corresponds to approximately 60 molecules/μm2, or 28 000 molecules per typical granulocyte (“Discussion”). Tethering of E-selectin–expressing CHO cells was reversed by pretreatment of adsorbed gangliosides with neuraminidase, by addition of anti–E-selectin antibody to the assay, or by removal of divalent cations from the perfusate (data not shown). For GSLs that supported tethering, rolling velocities generally decreased with increasing GSL density, but did not strictly correlate with tethering potency. For example, fractions 94 and 95 (Figure 4) both potently supported tethering, but rolling of CHO-E cells on adsorbed fraction 95 was much slower than on equivalent densities of fraction 94.

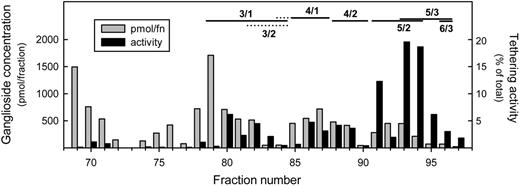

Dividing the concentration of ganglioside in each fraction by the minimal concentration required to support significant E-selectin tethering revealed the total E-selectin–binding activity in each fraction. This allowed us to plot the tethering activity in each fraction as a percentage of the total GSL tethering activity (Figure 5). The results focus attention on fractions 91, 93, and 94, which contain GSLs with 5 LacNAc repeats and 2 to 3 fucose residues. These fractions contain more than 50% of the total E-selectin tethering activity of human leukocytes. The most abundant GSL in these fractions contains 5 LacNAc repeats and 2 fucose residues (Table S1). To establish the fine structure of the major species in the most active HPLC fraction, a preparative column was used to prepare purified sialylated difucosylated neolactododecaosylceramide (5 LacNAc repeats). Total ion mapping MS and MSn of the released permethylated glycan revealed that more than 95% was a single species: NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (Figure 6; Figure S3). This purified GSL supported E-selectin–mediated tethering when adsorbed at 2 fmol/plate, confirming the structure of the major GSL in the most active fraction.

Distribution of E-selectin tethering activity among leukocyte gangliosides. The monosialoglycosphingolipids from human leukocytes were resolved by HPLC (Figure 4) and quantified based on A215 ( ). Total E-selectin tethering activity in each fraction was calculated by dividing the amount of ganglioside in that fraction by the minimal amount required to support significant E-selectin–mediated tethering. The resulting tethering activity in each fraction is plotted as a percentage of the total GSL tethering activity (■). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram (

). Total E-selectin tethering activity in each fraction was calculated by dividing the amount of ganglioside in that fraction by the minimal amount required to support significant E-selectin–mediated tethering. The resulting tethering activity in each fraction is plotted as a percentage of the total GSL tethering activity (■). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram ( indicates minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown, representing all of the E-selectin tethering activity and approximately 10% of the total leukocyte monosialo GSLs.

indicates minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown, representing all of the E-selectin tethering activity and approximately 10% of the total leukocyte monosialo GSLs.

Distribution of E-selectin tethering activity among leukocyte gangliosides. The monosialoglycosphingolipids from human leukocytes were resolved by HPLC (Figure 4) and quantified based on A215 ( ). Total E-selectin tethering activity in each fraction was calculated by dividing the amount of ganglioside in that fraction by the minimal amount required to support significant E-selectin–mediated tethering. The resulting tethering activity in each fraction is plotted as a percentage of the total GSL tethering activity (■). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram (

). Total E-selectin tethering activity in each fraction was calculated by dividing the amount of ganglioside in that fraction by the minimal amount required to support significant E-selectin–mediated tethering. The resulting tethering activity in each fraction is plotted as a percentage of the total GSL tethering activity (■). Fucosylated species detected by MALDI-TOF MS of the resolved fractions are designated above the chromatogram ( indicates minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown, representing all of the E-selectin tethering activity and approximately 10% of the total leukocyte monosialo GSLs.

indicates minor species), with structure abbreviations (n/m) as defined in Figure 1 legend. Only the trailing fractions of the HPLC run are shown, representing all of the E-selectin tethering activity and approximately 10% of the total leukocyte monosialo GSLs.

Sialylated difucosylated neolactododecaosylceramide from human leukocytes. The most potent E-selectin receptor glycosphingolipid was purified by preparative HPLC and subjected to MSn analysis to determine the relative distribution of fucose residues on the poly-LacNAc backbone. The major species, representing more than 95% of the isobaric structures present, is NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (IUPAC abbreviation: XII3NeuAc,VII3Fuc,IX3Fuc-nLc12Cer). Values are the means plus or minus SD for 5 isobaric distributions, each calculated from the relative abundances of different diagnostic fragment ions (Figure S3).

Sialylated difucosylated neolactododecaosylceramide from human leukocytes. The most potent E-selectin receptor glycosphingolipid was purified by preparative HPLC and subjected to MSn analysis to determine the relative distribution of fucose residues on the poly-LacNAc backbone. The major species, representing more than 95% of the isobaric structures present, is NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (IUPAC abbreviation: XII3NeuAc,VII3Fuc,IX3Fuc-nLc12Cer). Values are the means plus or minus SD for 5 isobaric distributions, each calculated from the relative abundances of different diagnostic fragment ions (Figure S3).

Glycosphingolipids are functional E-selectin receptors on human neutrophils

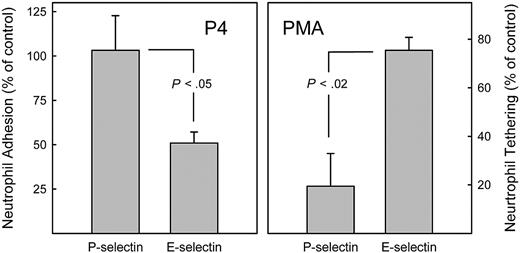

Fresh human neutrophils were cultured for 24 hours with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to maintain viability,39 then were treated for 24 hours with an inhibitor of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis, P4.46 Cells cultured in vitro (both control and P4 treated) lost sphericity, hampering analysis in the parallel plate flow assay. Nevertheless, static adhesion of cultured neutrophils to E-selectin–coated surfaces remained robust (adhesion was eliminated by anti–E-selectin antibody, data not shown). P4 treatment significantly reversed neutrophil–E-selectin adhesion, but had no affect on P-selectin adhesion (Figure 7 left panel). Because P4 specifically blocks the first step in GSL biosynthesis and does not affect glycoprotein biosynthesis,47,–49 these data support the hypothesis that GSLs are major E-selectin receptors on normal human neutrophils. Likewise (data not shown), treatment of cultured human neutrophils with 2 other GSL biosynthesis inhibitors threo-PDMP47 and NB-DGJ49 reversed neutrophil–E-selectin adhesion, whereas the inactive isomer of PDMP (erythro-PDMP) was without effect.

Differential effects of glycolipid biosynthesis inhibition and PMA activation on recognition of E- and P-selectins by primary human neutrophils. (Left) Inhibiting GSL biosynthesis inhibits E-selectin but not P-selectin adhesion. Neutrophils were isolated from peripheral venous blood and maintained in culture in medium containing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.39 After 24 hours, the glycosphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitor P4 was added (5 μM). After an additional 24 hours, cells were harvested, washed, labeled with 51Cr, and tested for adhesion to immobilized recombinant human P-selectin and E-selectin under static conditions as described.16,17 Cell adhesion is expressed relative to that of control cells cultured in the absence of P4. Data are from 3 (P-selectin) or 4 (E-selectin) independent experiments. (Right) Activation of human neutrophils with phorbol ester inhibits P-selectin but not E-selectin adhesion. Freshly prepared peripheral blood neutrophils were treated for 10 minutes with PMA (1.6 μM), then were perfused at 1 dyne/cm2 over monolayers of CHO-E or CHO-P cells as indicated. Tethering is expressed relative to that of control cells incubated in the absence of PMA. Data are from 3 independent experiments with SEM shown. Statistical comparisons are by Student t test.

Differential effects of glycolipid biosynthesis inhibition and PMA activation on recognition of E- and P-selectins by primary human neutrophils. (Left) Inhibiting GSL biosynthesis inhibits E-selectin but not P-selectin adhesion. Neutrophils were isolated from peripheral venous blood and maintained in culture in medium containing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.39 After 24 hours, the glycosphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitor P4 was added (5 μM). After an additional 24 hours, cells were harvested, washed, labeled with 51Cr, and tested for adhesion to immobilized recombinant human P-selectin and E-selectin under static conditions as described.16,17 Cell adhesion is expressed relative to that of control cells cultured in the absence of P4. Data are from 3 (P-selectin) or 4 (E-selectin) independent experiments. (Right) Activation of human neutrophils with phorbol ester inhibits P-selectin but not E-selectin adhesion. Freshly prepared peripheral blood neutrophils were treated for 10 minutes with PMA (1.6 μM), then were perfused at 1 dyne/cm2 over monolayers of CHO-E or CHO-P cells as indicated. Tethering is expressed relative to that of control cells incubated in the absence of PMA. Data are from 3 independent experiments with SEM shown. Statistical comparisons are by Student t test.

Activation of freshly isolated human neutrophils with PMA resulted in rapid shedding of PSGL-1,50 and inhibited cell tethering on P-selectin while having only a small effect on E-selectin adhesion (Figure 7 right panel). Together, these data support the conclusion that the major P-selectin and E-selectin ligands on human neutrophils are distinct, and that GSLs are major E-selectin, but not major P-selectin, ligands.

Discussion

Selectins and their receptors are required for inflammation as evidenced in patients with leukocyte adhesion deficiency type II, in which fucose use is compromised, leading to loss of selectin-leukocyte binding and impaired inflammation that is reversed by oral fucose administration.51,–53 Coordinate genetic ablation of E- and P-selectin in mice likewise results in leukocyte adhesion deficiency.54

After the structural relationship between selectins and C-type lectins was recognized,55 SLex was identified as a common binding determinant for all 3 selectins.6,,–9 However, the identity of functional selectin receptors on cells remained unknown. Varki proposed the following criteria to identify “real selectin ligands”: (1) they are expressed on the proper cells at the proper time; (2) their removal or blockade diminishes biologically relevant interactions; and (3) they bind with selectin selectivity and appropriate affinity.10

In light of these criteria, GSLs with 5 LacNAc repeats and 2 to 3 fucose residues are E-selectin ligands on human neutrophils. (1) They are in the right place. Fukuda et al40 isolated poly-LacNAc glycolipids, including fucosylated and sialylated species, from primary human granulocytes characterized as more than 95% neutrophils. In prior studies, we demonstrated that polar lipids extracted from human neutrophils that were more than 98% pure supported E-selectin– but not P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion.33 In this and prior studies,42,56,57 GSLs from primary human leukocytes were found to include monosialylated poly-LacNAc glycosphingolipids with 5 or more LacNAc repeats and 2 or more fucose residues. Together, these data indicate that human neutrophils express monosialylated fucosylated poly-LacNAc GSLs (myeloglycans) with E-selectin–binding capacity.

(2) Removal or blockade of myeloglycans abrogates biologically relevant interactions. Human neutrophil adhesion to E-selectin was reported to be sensitive to treatment with sialidase and endo-β-galactosidase (which cleaves poly-LacNAc structures), but resistant to proteases.14,16 Treatment of primary human neutrophils with 3 different inhibitors of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis diminished E-selectin–mediated adhesion without affecting P-selectin–mediated adhesion. For example, treatment of human neutrophils with the maximum tolerated concentration (5 μM) of the inhibitor P4 for 24 hours diminished E-selectin binding by half. Whether residual E-selectin binding was due to alternate receptors or incomplete clearance of GSLs has yet to be determined. However, together with the relative protease resistance of E-selectin binding,14 a role for GSLs as quantitatively major E-selectin receptors is supported.

(3) The binding selectivity and avidity of myeloglycans is appropriate for their biologic activity. In the current study, leukocyte GSLs were adsorbed as membrane monolayers to approximate the outer leaflet of a plasma membrane and provide reasonable estimates of the minimum molecular densities that support E-selectin–mediated cell tethering and rolling in a biologically relevant context. More than half of the E-selectin tethering activity was carried by sialylated, difucosylated and trifucosylated neolactododecaosylceramides (Figure 2, 5/2 and 5/3). These glycans supported E-selectin tethering when deposited at 5 fmol per 5-mm diameter area. Assuming an adsorption efficiency of 40%,34 tethering was supported by 2 fmol in an area of approximately 20 mm2, or 60 molecules/μm2. How does this density for E-selectin tethering compare with the density of the same molecules on leukocytes? Analysis of lipid-bound sialic acid in the current study revealed 40 amol monosialo GSL per cell of which the 5/2 and 5/3 structures represented 2%, or 0.8 amol/cell. Based on the surface area of the neutrophil (456 μm2/cell),58 the combined surface density of structures 5/2 and 5/3 is approximately 1000 molecules/μm2, well above the 60 molecules/μm2 minimally required. In the parallel plate flow assay, structures 5/2 and 5/3 adsorbed at surface densities of less than 1000 molecules/μm2 supported extensive E-selectin tethering (> 600 cells/mm2) and rolling (5-14 μm/s).

The experiments reported here reveal the GSL density required to support E-selectin tethering, but not the site affinity of E-selectin for individual GSLs. Lateral mobility of GSLs and self-association may generate multivalent arrangements that enhance the avidity of GSLs, both on the membrane monolayers tested here and on cell surfaces. In mice, clustering of selectin glycoprotein ligands is associated with neutrophil activation and arrest.59 Likewise, on human neutrophils capping of selectin glycoprotein ligands has been linked to integrin activation.60 Although signaling cascades downstream of E-selectin–GSL binding have yet to be elucidated, clustering of GSLs is associated with integrin modulation in other cell types.61

Together, functional and analytical data indicate that GSLs carrying the terminal glycan nonasaccharide NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2-R constitute major E-selectin receptors on human leukocytes. This conclusion is consistent with earlier findings using myeloglycans purified from HL-60 cells,20,21 although the predominance of 5/2 and 5/3 structures as the major E-selectin receptors of human neutrophils was not anticipated. The current studies established that this nonasaccharide terminus is most potent in supporting E-selectin tethering when carried on the 5/2, 5/3, and 6/3 structures (Figure 4). These data do not rule out a role for glycoproteins as quantitatively minor E-selectin ligands on human leukocytes (eg, PSGL-1; Figure 7 right panel) or as major E-selectin ligands on other cell types.

Fucosylation increased with the length of the poly-LacNAc core. Structures with 1 or 2 LacNAc repeats are devoid of fucose, whereas fucose was found on 20% of the GlcNAc residues on structures with 3 LacNAc repeats, 35% of GlcNAc residues on structures with 4 LacNAc repeats, and 46% to 48% of GlcNAc residues on structures with 5 to 6 LacNAc repeats. This implies that longer structures are enhanced fucosyltransferase acceptors or selectively pass through biosynthetic compartments with greater fucosyltransferase activity.

Given the role of VIM-2–terminated GSLs as E-selectin ligands, their biosynthesis may impact inflammation. Fucosyltransferase 4 (FUT4 gene) is expressed by granulocytes, preferentially fucosylates glycolipids,62 and preferentially fucosylates internal GlcNAc residues (eg, VIM-2; Figure 1 inset) compared with terminal-most GlcNAc residues (eg, SLex).43 The other major fucosyltransferase of human granulocytes, fucosyltransferase 7 (FUT7 gene), is not known to catalyze internal fucosylation.43 In the current study, monosialo GSLs with fucose solely on the terminal-most GlcNAc (SLex) were found only on shorter GSL structures; there was little terminal-most GlcNAc fucosylation on the more active E-selectin–binding structures having 5 to 6 LacNAc repeats. These data suggest that fucosyltransferase 7 is not significantly involved in biosynthesis of human leukocyte E-selectin receptors. Based on genetic experiments in mice, the contributions by Fut4 to E-selectin ligand biosynthesis are thought to be superseded by Fut7.62,–64 However, the major E-selectin receptors on mouse neutrophils are biochemically distinguishable from those on human neutrophils,14 and the respective roles of FUT4 and FUT7 gene products on E-selectin ligand biosynthesis in human neutrophils may differ from those in mice.

The current data, along with prior reports, support assignment of the following structure (and closely related structures) as major human neutrophil E-selectin receptors: NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (XII3NeuAc,VII3Fuc,IX3Fuc-nLc12Cer).

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Fromholt for technical assistance and Dr Christine L. Martens for supplying stable selectin transfectants. Voyager MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy was performed at the AB Mass Spectroscopy/Proteomics Facility at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

This work was supported by grant AI45115 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Bethesda, MD) and a fellowship from the Committee for Postgraduate Courses in Higher Education (CAPES, Brasilia, Brazil), Ministry of Education, Federal Government of Brazil (L.N.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: L.N., M.M.B., W.L., and M.A.F. purified and quantified leukocyte glycolipids and tested selectin-mediated adhesion; K.A. and M.T. performed and interpreted total ion mapping mass spectrometry; C.E.V.S. and R.J.C. performed and interpreted MALDI mass spectrometry; S.A.H. purified and characterized human leukocytes and performed leukocyte cell adhesion; and B.S.B., K.K., and R.L.S. conceived and designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ronald L. Schnaar, Department of Pharmacology & Molecular Sciences, The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 725 N Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205; e-mail: schnaar@jhu.edu.

References

Supplemental data

Primary data from total ion mapping nanospray ionization MSn performed on permethylated oligosaccharides released from the monosialoglycosphingolipid fraction purified from human leukocytes. For fucosylated species, MSn data are provided that allow assignment of the positions of the Fuc residues on the corresponding poly-LacNAc chain. Details of the method can be found in the text and in Aoki, et al. (Aoki, K., Perlman, M., Lim, J. M., Cantu, R., Wells, L., and Tiemeyer, M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9127-9142). Structures are abbreviated as “n/m” where n is the number of LacNAc repeats and m the number of fucoses in the general structure NeuAcα2¬3Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)0–1GlcNAcβ1-3nGalβ1-4GlcβCer. Symbol nomenclature is that adopted by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://glycomics.scripps.edu/CFGnomenclature.pdf).

The following pages contain primary data from total ion mapping nanospray ionization MSn performed on the permethylated oligosaccharides released from the major E-selectin binding glycosphingolipid from human leukocytes. MSn data are provided that allow assignment of the positions of the Fuc residues on the poly-LacNAc chain. Details of the method can be found in the text and in Aoki, et al. (Aoki, K., Perlman, M., Lim, J. M., Cantu, R., Wells, L., and Tiemeyer, M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9127-9142). The “5/2” designation refers to general structure NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4 (Fucα1-3)0–1GlcNAcβ1-3nGalβ1-4GlcβCer, in which there are 5 LacNAc repeats and 2 fucose residues. Symbol nomenclature is that adopted by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://glycomics.scripps.edu/CFGnomenclature.pdf).

![Figure 1. MALDI-TOF MS of purified human leukocyte monosialoglycosphingolipids. The monosialo GSL fraction from human leukocytes was subjected to MALDI-TOF MS. Peaks corresponding to masses of glycosphingolipids 110 mass units separated, reflecting the presence of the same glycan species bearing either C16:0 or C24:1 fatty acid amides, are indicated. The proposed structures are abbreviated as n/m where n is the number of LacNAc repeats and m the number of fucoses in the general structure NeuAcα2-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)0-1GlcNAcβ1-3]nGalβ1-4GlcβCer. The inset structure, 3/1, was isolated from human leukemia cells and contains 3 LacNAc repeats (one of which is fucosylated) and the VIM-2 structure19 (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry [IUPAC, Research Triangle Park, NC] designation: VIII3NeuAcV3Fuc-nLc8Cer).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/9/10.1182_blood-2008-04-149641/5/m_zh80180823890001.jpeg?Expires=1769094684&Signature=jCvYIIFrzDnRpgLt8FjtFbQAYyHdhyNQODk00DkY8UvZpdPlerCIP3S8Uoc2rSXMEHtSHQVpLDa0NhmB1OVeo4XwLa9pFtMagqXoKbT4~bVgwq9PNDR~hcmiRApztjrLm3WLtvK~iWyjrzOdc6-mRX5swfsmKePe9xyniIH4wLc4aVCN824H087X8Wsib6pxBo1sDzVFyWjJMvinO0epPJ-FCTe1NcXQDSJAs6GLCcG~spMgiIjj29Rucjpw2swrtTzk0pVft8sF9sRHwPBCbAhZ8~4qClaQKiRGatVnaNTPlaIsb4hKZdcGmitAFPEX0M~9~llU6Hd2N-zVvshESQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Sialylated difucosylated neolactododecaosylceramide from human leukocytes. The most potent E-selectin receptor glycosphingolipid was purified by preparative HPLC and subjected to MSn analysis to determine the relative distribution of fucose residues on the poly-LacNAc backbone. The major species, representing more than 95% of the isobaric structures present, is NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (IUPAC abbreviation: XII3NeuAc,VII3Fuc,IX3Fuc-nLc12Cer). Values are the means plus or minus SD for 5 isobaric distributions, each calculated from the relative abundances of different diagnostic fragment ions (Figure S3).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/9/10.1182_blood-2008-04-149641/5/m_zh80180823890006.jpeg?Expires=1769094684&Signature=L2c21Edt6oc6onZ~KTJMv9azq5ByUpplse~LBikk2GZJFm32WH5uQ-06UTLphtnArnLpP7nalaqyGQMgUH9E5dw98odZ9jPNPK9sPqWmiKaEQQvUZg9jqyjo9wX3EBxzGn4nf9dAIx5SvOzTAYDa7MOFYyiBB48cuBrgfYt5RsJzl2CvXmt5jmQ7uxU4SvmNUsLHFNcSNGB42BkdZp5n~yHhX5D7UdIQPV7lxxbe70s43kDro27WhStSfNjFIg~SLV4JnFEYelEKhofrn2U-7vICTZZTqw-Hm2wMGgQzMdClqXEnsX7rfBP-Muz41zaT-TxmPA07IN6dDpHwhGr7dA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal