Abstract

Neutrophils have a very short life span and undergo apoptosis within 24 hours after leaving the bone marrow. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is essential for the recruitment of fresh neutrophils from the bone marrow but also delays apoptosis of mature neutrophils. To determine the mechanism by which G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis, the kinetics of neutrophil apoptosis during 24 hours in the absence or presence of G-CSF were analyzed in vitro. G-CSF delayed neutrophil apoptosis for approximately 12 hours and inhibited caspase-9 and -3 activation, but had virtually no effect on caspase-8 and little effect on the release of proapoptotic proteins from the mitochondria. However, G-CSF strongly inhibited the activation of calcium-dependent cysteine proteases calpains, upstream of caspase-3, via apparent control of Ca2+-influx. Calpain inhibition resulted in the stabilization of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) and hence inhibited caspase-9 and -3 in human neutrophils. Thus, neutrophil apoptosis is controlled by G-CSF after initial activation of caspase-8 and mitochondrial permeabilization by the control of postmitochondrial calpain activity.

Introduction

Neutrophils, the primary phagocytic cells of the human immune system, have a very short life span after leaving the bone marrow of approximately 24 hours. Thereafter, they die either by intrinsically or extrinsically induced apoptosis. Extrinsically, neutrophil apoptosis can be activated through the ligation of death receptors, such as Fas/CD95 or other receptors of the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) family.1,2 Intrinsically, neutrophil apoptosis appears to be regulated at the level of their mitochondria and involves the spontaneous clustering of death receptors3 or release of cathepsin D,4 but many details about intrinsic, or spontaneous, neutrophil apoptosis remain unclear.5,6

A vitally important factor for the recruitment of fresh neutrophils from the bone marrow is granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).7,8 G-CSF has previously been shown to inhibit neutrophil apoptosis both in vivo9 and in vitro10 and is widely used in a clinical setting to treat various conditions associated with severe neutropenia. Healthy donors are also given G-CSF before a peripheral hematopoietic stem cell or granulocyte donation.

Most studies on G-CSF signaling have been done with the murine myeloblast cell line 32D clone 3 (32Dcl3). In this cell line, signal transduction of the G-CSF receptor occurs via the Janus kinase (Jak)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT-3) pathway.11-13 These studies mainly focused on neutrophil differentiation, and little as yet is known about the inhibition of apoptosis by G-CSF in primary human neutrophils.

Previous studies in our lab have indicated that G-CSF primarily inhibits apoptosis by preventing the activation of the executioner of apoptosis, the cysteine protease caspase-3.10,14 Caspase-3 is activated downstream of the initiators of apoptosis, caspase-8 and -9. Caspase-8 is activated after death receptor clustering, which occurs spontaneously during neutrophil apoptosis, while caspase-9 activation normally occurs after the release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria, including Smac. When Smac is released from the mitochondria, it competes with caspase-9 and -3 for binding to the so-called inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs). The main member of this protein family of IAPs that is present in neutrophils and responsible for the inhibition of both caspase-9 and -3 is the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP).14-16 Several other IAP family members have been identified in neutrophils and are implicated in neutrophil apoptosis,17,18 but it has recently become clear that only XIAP is a true inhibitor of caspase activation.19-21 Both caspase-9 and caspase-3 can become activated only after they have been released from XIAP by Smac.22,23 Caspase-8 controls the release of Smac from the mitochondria via cleavage of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bid. Truncated Bid (tBid) is involved in the activation and mitochondrial translocation of another proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bax, and subsequent permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane.24

Several studies have implicated calpain activity in spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis.25,26 Calpains are a family of calcium-dependent cysteine proteases of which calpain-1 (μ-calpain, calpain I), calpain-2 (m-calpain, calpain II) and the natural inhibitor of calpains, calpastatin, are ubiquitously expressed. Additional, more tissue-specific, isoforms of the calpains have also been identified, but these are not expressed in neutrophils.27 Calpain-1 has been shown to be involved in the activation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bax in human neutrophils.28 In chronic neutrophilic leukemia, calpain activation and subsequent degradation of XIAP is impaired, leading to increased neutrophil survival.16 Thus, calpain activation plays an important role in the regulation of neutrophil apoptosis, both by activation of proapoptotic factors as well as by the degradation of antiapoptotic proteins.

For this study, several apoptotic parameters at various time points during 24 hours of neutrophil incubation in the absence or presence of G-CSF was monitored. We show that G-CSF inhibits phosphatidyl serine (PS) exposure and the morphologic features of apoptosis but has no effect on the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of Smac from the mitochondria. Although incubation with G-CSF did inhibit the activation of caspase-9 and -3, activation of caspase-8 was not prevented. We show that G-CSF inhibits the activation of calpains and limits the increase in intracellular Ca2+ during neutrophil apoptosis. As an apparent consequence of this inhibition, XIAP degradation is prevented and the downstream activation of caspase-9 is delayed, resulting in inhibition of cell death. Thus, G-CSF controls neutrophil apoptosis downstream of the mitochondria at the level of caspase activation.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against caspase-3, caspase-8 (1C12), caspase-9, Bid and Smac/Diablo were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Anti–human ASC was obtained from Medical&Biological Laboratories (MBL Woburn, MA). The anti–Mn-SOD antibody was obtained from Stressgen Biotechnologies (Victoria, BC). Rabbit anti–human-Bax was obtained from BD Biosciences (Erembodegem, Belgium) and mouse anti–human-hILP/XIAP (clone 48) was obtained from BD Biosciences. All chemical reagents were obtained from Merck Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany), unless otherwise indicated.

Cell preparation and culture

Neutrophils were isolated from the heparinized blood of healthy human subjects by centrifugation over isotonic Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and subsequent lysis of erythrocytes as described.29 Neutrophil preparation were typically greater than 97% pure, with the contaminating cells being mostly eosinophils. Cells were cultured in Hepes-buffered saline solution (HBSS; 132 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1% human serum albumin (Cealb; Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and 5 mM glucose at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL in polypropylene round-bottom tubes of 14 mL (BD Biosciences). Incubations were performed in a shaking water bath at 37°C. Cells were incubated in the presence of 10 ng/mL clinical grade G-CSF (Neupogen; Amgen, Breda, The Netherlands) where indicated.

Cell fractionation and Western blot

Subcellular fractions were prepared of 5 × 106 cells by washing the cells once in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before resuspension in cytosol extraction buffer (250 mM sucrose, 70 mM KCl, 250 μg/mL digitonin, complete protease inhibitor cocktail mix [PIM; Roche Diagnostics, Almere, The Netherlands] and 2 mM diisopropylfluorophosphate [DFP; Fluka Chemica, Steinheim, Switzerland] in PBS) at a concentration of 100 × 106 cells/mL. Cells were incubated for 10 minutes. on ice, after which they were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1000g, 4°C. The supernatant represented the cytosolic fraction, the pellet, containing the mitochondria, was dissolved in mitochondrial lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 1% [vol/vol] NP-40, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol [Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO], PIM, 2 mM DFP in 50 mM TrisHCl buffer at pH 7.5) and incubated for another 10 minutes on ice. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 minutes. at 4°C. The supernatant, containing the mitochondrial content, represented the membrane fraction. The insoluble pellet was discarded. Both fractions were dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer (LSB; 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol [vol/vol], 5 mM DTT [DL-dithiothreitol, Sigma-Aldrich], 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% sodiumdodecylsulphate [SDS; mass/vol], 100 μg/mL bromephenol blue) and boiled for 10 minutes at 95°C.

Total cell lysates were prepared by lysing the cells in cell lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 70 mM KCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 [vol/vol], 0.5% β-octylglucoside [vol/vol], 2 mM NaVO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, PIM and 2 mM DFP in PBS) for 30 minutes on ice. Afterward, the samples were dissolved in LSB and boiled for 30 minutes at 95°C. All samples were stored at −20°C before subjection to SDS-polyacrylamide gelelectrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Samples were run on 12%, 1.5-mm polyacrylamide gels in a Protean-3 mini system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Veenendaal, The Netherlands). The equivalent of 1.5 × 106 cells was loaded in each lane. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (PVDF; Bio-Rad), which were subsequently blocked for 30 minutes with blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk [mass/vol; Elk; Campina, Zaltbommel, The Netherlands] in Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween-20 [vol/vol; TBST]). Blots were immuno-labeled with specific antibodies against the indicated proteins in blocking buffer containing 2 mM NaN3, overnight at 4°C. After washing the blots in TBST, they were treated with horseradish peroxidase–labeled secondary antibodies directed against the primary antibodies (donkey anti–rabbit-IgG or sheep anti–mouse-IgG, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Labeling was followed by another round of washing in TBST before detection of the specific signals with Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) on Fuji medical X-ray film (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Flow cytometry

To detect apoptosis, cells were labeled for 10 minutes on ice with fluorescein-thiocyanate (FITC)–labeled annexin V (Bender Med Systems, Vienna, Austria), diluted 1:500 in HBSS, supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2. Annexin V labeling was followed by a single wash step with the same medium, whereupon the cells were resuspended in HBSS 2.5 mM CaCl2 containing 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich). After an additional 5 minutes. on ice, the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Surviving cells were defined as the cells in the lower left quadrant that stained negative for both annexin V and PI.

To detect changes in ▵ψm, the cells were loaded for 15 minutes. at 37°C with 0.5 μM JC-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in HBSS, containing 1 μM tetraphenyl boron to facilitate entry of the dye into the cells, and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry. To determine a background value for ▵ψm, cells were incubated with 1 μM CCCP (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), which is sufficient to completely abrogate ▵ψm. Cells with high ▵ψm were defined as the population of cells with high fluorescence in the FL-2 (red) channel (10 < fluorescence intensity < 1000) that did not include cells that were treated with CCCP.

Surface expression of CXCR4 and CD16 was detected by incubating the cells for 30 minutes at room temperature with a phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled antibody directed against CXCR4 (BD Pharmingen) and a FITC-labeled antibody directed against CD16 (Sanquin). Both antibodies were diluted 1:200 in HBSS. After washing, the samples were analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Calpain and caspase assay

Calpain and caspase-3 activities were determined in cytosolic extracts, prepared in the same way as for the subcellular fractions. Samples were stored at 4°C until use. Protein concentration in the samples was determined with the BCA protein assay kit from Pierce. Protease activity was determined by the addition of 100 μL reaction buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM CaCl2 and 20 μM fluorescent substrate for caspase-3 [Ac-IETD-AMC; Alexis Biochemicals, Lausen, Switzerland] or Calpain Substrate II [Suc-LY-AMC; Calbiochem] for calpains) to 10 μL of the sample, containing 4 mg protein/mL. The fluorescence increase was measured in a SpectraFluo Plus spectrophotometer (Tecan, Zürich, Switzerland) at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm after 2 hours of incubation at 37°. As controls, intact cells or samples with high protease activity (8 hours, untreated) were treated with 20 μM of the cell permeable pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VADfmk (Alexis Biochemicals) or 20 μM of the broad spectrum Calpain-Inhibitor-3 (CI3; Calbiochem).

Determination of cytosolic free Ca2+

Cytosolic free Ca2+ was determined by loading the cells with 1 μM of the Ca2+-indicator fluo-3 acetoxylmethyl (AM) ester (Molecular Probes) for 45 minutes at 37°C. After loading, the cells were washed once in HBSS, resuspended in HBSS containing 1 μL/mL antifluorescein antibody (Molecular Probes) to quench extracellular Fluo-3, at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL, and transferred to the quartz cuvettes of a fluorometer, after which 10 ng/mL G-CSF was added to one of the samples. As controls, samples were measured of cells loaded with 10 μM BAPTA-AM or of cells incubated in medium without Ca2+. The increase in fluorescence was measured every minute for 12 hours under continuous stirring. At the end of a run, the cells were permeabilized by addition of 2 μg/mL digitonin to determine the maximum fluorescence (Fmax). Minimum fluorescence (Fmin) was determined after addition of 5 mM EDTA.

Statistical analysis and image processing

Graphs were drawn and statistical analysis was performed with Prism 4.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The results are presented as the mean plus or minus SEM or SD, as indicated. Data were evaluated by paired, 1-tailed Student t test, where indicated. The criterion for significance was P less than .05 for all comparisons. Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and CorelDRAW 11 (Corel, Ottawa, ON).

The ethics committee of Sanquin Research approved this study. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis

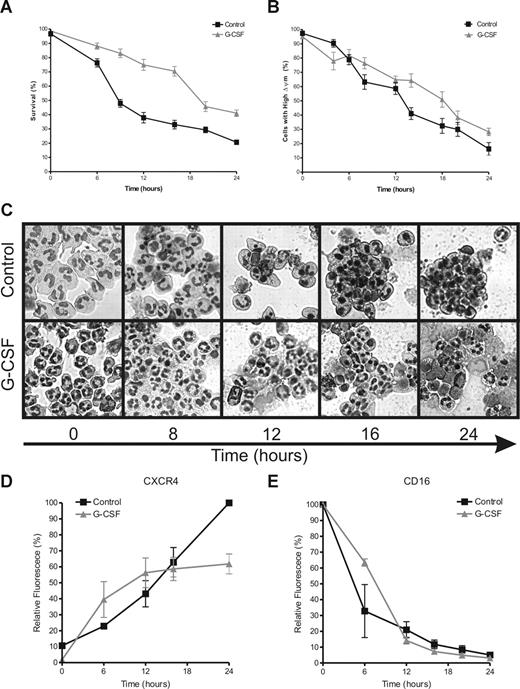

A common marker for apoptotic cells is PS exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. PS exposure was monitored on neutrophils during incubation in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF. In Figure 1A, the percentage of cells is shown that stain negative for both annexin V (as a marker for PS) and PI (as a marker for membrane-permeable late-apoptotic or necrotic cells). After 6 hours of incubation, PS exposure accelerated rapidly on the control neutrophils. A similar acceleration was not seen in the G-CSF–treated neutrophils until after 16 hours of incubation, in all 6 donors included in this study. Although G-CSF significantly inhibited the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (▵ψm), associated with the release of proapoptotic proteins from the mitochondrial intermembrane space,30-32 this process still proceeded gradually in the G-CSF–treated cells as in the control cells (Figure 1B). To analyze the morphology of the neutrophils for apoptotic features, cytospins of the cells were prepared at the indicated time points and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa stain before analysis by light microscopy. Morphologic changes of the neutrophils, such as cell shrinkage and nuclear condensation, matched the exposure of PS, as shown in Figure 1C.

G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of G-CSF (10 ng/mL). Samples were taken at various times to determine the indicated hallmarks of apoptosis. (A) Cells were stained with FITC-labeled annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of double negative cells is expressed as survival. (B) Cells were loaded with the ▵ψm-sensitive dye JC-1 and analyzed by flow cytometry. When JC-1 accumulates in mitochondria with a high ▵ψm it displays red fluorescence (FL-2), while the dye is green fluorescent (FL-1) when ▵ψm is low. The percentage of cells with a high ▵ψm is expressed in this graph, corrected for background staining (ie, the JC-1 fluorescence of cells treated with 1 μM of the uncoupler CCCP). The average slope for the loss of ▵ψm in the control cells was −3.53 plus or minus 0.1801, SEM) %/h, while the average slope for the G-CSF–treated cells was −2.66 plus or minus 0.1927, SEM) %/h. The difference between the slopes is highly significant with a P value of .001. (C) Cells (2 × 105) were spotted on microscopy glasses and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa stain before analysis with a light microscope. Pictures were taken at 40× magnification and are representative of 6 different experiments. (D,E) Cells were double labeled for CXCR4 and CD16 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as a percentage of the maximum fluorescence for the control sample at 0 hours for CD16 and 24 hours for CXCR4. All graphs represent the means (± SEM) of 6 different experiments performed in duplicate.

G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of G-CSF (10 ng/mL). Samples were taken at various times to determine the indicated hallmarks of apoptosis. (A) Cells were stained with FITC-labeled annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of double negative cells is expressed as survival. (B) Cells were loaded with the ▵ψm-sensitive dye JC-1 and analyzed by flow cytometry. When JC-1 accumulates in mitochondria with a high ▵ψm it displays red fluorescence (FL-2), while the dye is green fluorescent (FL-1) when ▵ψm is low. The percentage of cells with a high ▵ψm is expressed in this graph, corrected for background staining (ie, the JC-1 fluorescence of cells treated with 1 μM of the uncoupler CCCP). The average slope for the loss of ▵ψm in the control cells was −3.53 plus or minus 0.1801, SEM) %/h, while the average slope for the G-CSF–treated cells was −2.66 plus or minus 0.1927, SEM) %/h. The difference between the slopes is highly significant with a P value of .001. (C) Cells (2 × 105) were spotted on microscopy glasses and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa stain before analysis with a light microscope. Pictures were taken at 40× magnification and are representative of 6 different experiments. (D,E) Cells were double labeled for CXCR4 and CD16 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as a percentage of the maximum fluorescence for the control sample at 0 hours for CD16 and 24 hours for CXCR4. All graphs represent the means (± SEM) of 6 different experiments performed in duplicate.

During neutrophil aging, expression of the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is increased on the outer membrane of the cells (Figure 1D). Neutrophil maturation in the bone marrow is associated with a decrease in CXCR4 expression, which is induced by G-CSF and leads to the release of mature cells into the circulation.33 During the first 12 hours of neutrophil incubation, G-CSF did not have a significant effect on CXCR4 exposure. However, after 12 hours, G-CSF prevented the further increase in CXCR4 exposure, while the expression of this marker continued to rise on the untreated cells (Figure 1D). Shedding of the Fcγ receptor IIIb (CD16), another hallmark of neutrophil apoptosis,34,35 was not affected by G-CSF at these time points (Figure 1E). This finding is surprising, because GM-CSF, another potent inhibitor of neutrophil apoptosis, has been described to preserve CD16 expression.36

G-CSF inhibits cleavage of caspase-3 and -9, but not caspase-8

In healthy cells, caspases are present as inactive zymogens, while active caspases are obligate dimers of identical catalytic subunits.37 After a proapoptotic stimulus, caspases first dimerize, after which their p10/p12 domain is cleaved off by autocatalysis, revealing the active sites in the p20/p22 domain. Full activation only occurs after a second cleavage event has released the p20/p22 domain. The fully activated caspase consists of a dimer of 2 p10/p12 and 2 p17/p18 subunits. Caspases are activated in sequence, starting with the initiator, caspase-8, which is activated after forced oligomerization at the death receptors. One of the main targets of active caspase-8 is the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bid. After Bid has been cleaved by caspase-8 (tBid), it associates with Bax at the mitochondria to form the permeability transition pore, through which the proapoptotic proteins that activate caspase-9 are released.24 Finally, caspase-9 activates the executioner caspase-3 and apoptosis ensues.

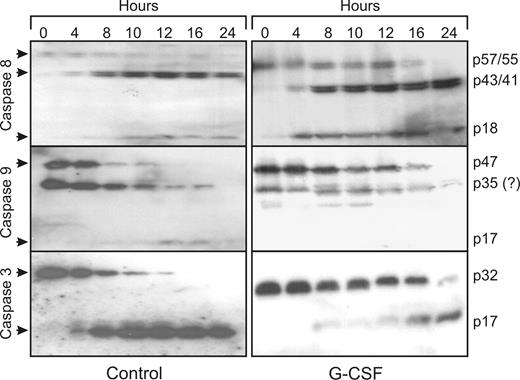

During spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, caspase-8, -9, and -3 are rapidly activated. The cleavage products of the active caspases can already be spotted on Western blot after 4 hours (Figure 2). For caspase-8, which has 2 splice variants in neutrophils, the appearance of the semiactive caspases (p43/p41) is most readily detected with the antibody used in this study, while the inactive forms (p57/p55) gradually disappear and the appearance of the fully active form can vaguely be detected (p18). For caspase-9, the disappearance of the full-length caspase (p47) is most readily detected. At approximately 35 kDa, a band is visible on the blot that could be the semi active caspase p35, but because this band is also detected in fresh cells, it is not deemed likely that this is a cleavage product of capsase-9. It could be a nonspecific band instead. On the caspase-3 blots, both the disappearance of the full-length caspase (p32) as well as the appearance of the cleavage product (p17) can be detected. After 12 hours, all caspases are completely cleaved, showing that caspase activation precedes PS exposure and morphologic changes. Although G-CSF inhibits the activation of caspase-9 and -3 for at least 12 hours, corresponding with the 12-hour delay in PS exposure, caspase-8 activation was not affected. Thus, G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis downstream of caspase-8 activation.

G-CSF inhibits the activation of caspase-9 and -3, but not of caspase-8. Samples of neutrophils incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF were taken at the indicated times, subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed on Western blots, stained with antibodies against the indicated caspases.  indicates the full-length, inactive caspases and their cleavage products after activation. Equal amounts of cells (1.5 × 106), dissolved in sample buffer, were loaded in each lane. All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

indicates the full-length, inactive caspases and their cleavage products after activation. Equal amounts of cells (1.5 × 106), dissolved in sample buffer, were loaded in each lane. All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

G-CSF inhibits the activation of caspase-9 and -3, but not of caspase-8. Samples of neutrophils incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF were taken at the indicated times, subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed on Western blots, stained with antibodies against the indicated caspases.  indicates the full-length, inactive caspases and their cleavage products after activation. Equal amounts of cells (1.5 × 106), dissolved in sample buffer, were loaded in each lane. All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

indicates the full-length, inactive caspases and their cleavage products after activation. Equal amounts of cells (1.5 × 106), dissolved in sample buffer, were loaded in each lane. All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

G-CSF inhibits neither the translocation of Bax and Bid nor the release of mitochrondrial Smac

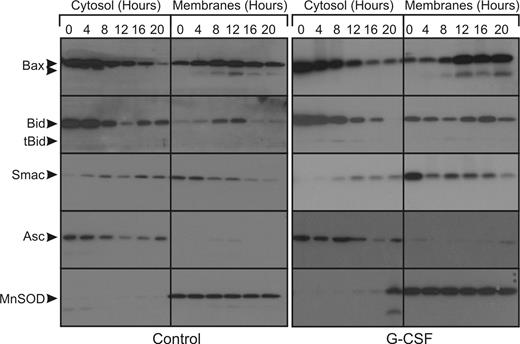

The proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bid are both abundantly present in the cytosol of fresh neutrophils. During apoptosis, both proteins translocate to the mitochondria to initiate the formation of the permeability transition pore in the outer mitochondrial membrane, through which Smac and other proapoptotic proteins can be released. A certain amount of Bax is already present on the mitochondria of healthy cells, where it is counteracted by antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members such as Mcl-1.38,39 To detect the translocation of the activated proteins to the mitochondria and the release of Smac from the mitochondria, we extracted the cytosol from neutrophils after permeabilization of the plasma membrane with digitonin at the indicated time points. The remaining pellet, containing the mitochondria, was dissolved in a buffer containing NP40. Both fractions were analyzed on Western blot.

In the untreated cells, an increase in mitochondrial Bax can be seen from 4 hours onward (Figure 3) in the membrane fraction. Cleaved, active Bax also appears in the membranes fraction from 4 hours onwards. The increase in mitochondrial Bax occurs concomitantly with a decrease in cytosolic Bax. In the same period, Bid is gradually cleaved and also translocates to the mitochondria-enriched membranes fraction. Smac is exclusively present in the membranes fraction of fresh cells, but translocation of Smac from the mitochondria to the cytosol already occurs after 4 hours. In the G-CSF–treated cells, these events occur from 8 hours onwards. Thus, G-CSF delays mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization for approximately 4 hours, while caspase activation is delayed for at least 12 hours.

G-CSF does not inhibit the release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria during apoptosis. Untreated neutrophils or neutrophils treated with 10 ng/mL G-CSF were fractionated at the indicated time points. The cytosolic fractions, which contain no mitochondria, and the pellet fractions, which are enriched for mitochondria, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed on Western blots stained for the indicated proteins.  indicates the full-length proteins and cleavage products in the cases of Bax and Bid. Blots were reprobed for ASC (cytosolic) and MnSOD (mitochondrial matrix) to control for cross contamination and protein loading (bottom panels). All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

indicates the full-length proteins and cleavage products in the cases of Bax and Bid. Blots were reprobed for ASC (cytosolic) and MnSOD (mitochondrial matrix) to control for cross contamination and protein loading (bottom panels). All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

G-CSF does not inhibit the release of proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria during apoptosis. Untreated neutrophils or neutrophils treated with 10 ng/mL G-CSF were fractionated at the indicated time points. The cytosolic fractions, which contain no mitochondria, and the pellet fractions, which are enriched for mitochondria, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed on Western blots stained for the indicated proteins.  indicates the full-length proteins and cleavage products in the cases of Bax and Bid. Blots were reprobed for ASC (cytosolic) and MnSOD (mitochondrial matrix) to control for cross contamination and protein loading (bottom panels). All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

indicates the full-length proteins and cleavage products in the cases of Bax and Bid. Blots were reprobed for ASC (cytosolic) and MnSOD (mitochondrial matrix) to control for cross contamination and protein loading (bottom panels). All blots are representative of at least 4 independent experiments.

To control for cross-contamination of the fractions, the blots were stained for either the cytosolic adaptor protein ASC or the mitochondrial matrix protein MnSOD, as shown in the bottom panels of Figure 3. Only in the latest time point was MnSOD also found in the cytosol fraction, indicative of complete degradation of the mitochondria at this time point.

G-CSF delays the gradual rise of intracellular Ca2+ during neutrophil apoptosis

Previously, it has been noted that neutrophil apoptosis is associated with a rise in the basal levels of intracellular Ca2+.25,40 Because we observed that most events relevant for apoptosis occur during the first 12 hours of neutrophil culture, we decided to monitor the changes in intracellular Ca2+ during this period. In 12 hours, intracellular Ca2+ rises to approximately 1.5 μM in unstimulated cells, while Ca2+ levels in G-CSF–stimulated cells did not reach 0.5 μM in the same period (Figure 4A). When the cells were incubated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, intracellular Ca2+ levels did not rise significantly, suggesting that the observed was due to extracellular influx. In addition, prevention of the rise in intracellular Ca2+ by treating neutrophils with the cell permeable Ca2+-chelator BAPTA-AM (Figure 4A), strongly promoted survival in a concentration-dependent manner after 18 hours in culture (Figure 4B), as indicated by annexin V staining. These observations were confirmed on cytospins of the same samples, stained by May-Grünwald Giemsa stain and analyzed by light microscopy (not shown). Thus, the observed rise in intracellular Ca2+ seems to be a requirement for neutrophil apoptosis.

G-CSF inhibits the steady increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ during neutrophil aging, which is essential for apoptosis. Neutrophils were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-3 and incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF in the stirred cuvette of a fluorometer, while the increase in fluorescence was measured every minute for 12 hours. As controls, cells where loaded with 10 μM of the cell permeable Ca2+-chelator BAPTA-AM or incubated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (A). Data represent the average of 3 independent experiments. An increase in intracellular free Ca2+ is a requirement for the process of neutrophil apoptosis, because treating the cells with an increasing dose of BAPTA-AM induced up to 75% neutrophil survival at 10 μM after 18 hours of incubation (B). The percentage of surviving cells is expressed as a lack of annexin V/PI staining determined by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

G-CSF inhibits the steady increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ during neutrophil aging, which is essential for apoptosis. Neutrophils were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-3 and incubated in the presence or absence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF in the stirred cuvette of a fluorometer, while the increase in fluorescence was measured every minute for 12 hours. As controls, cells where loaded with 10 μM of the cell permeable Ca2+-chelator BAPTA-AM or incubated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (A). Data represent the average of 3 independent experiments. An increase in intracellular free Ca2+ is a requirement for the process of neutrophil apoptosis, because treating the cells with an increasing dose of BAPTA-AM induced up to 75% neutrophil survival at 10 μM after 18 hours of incubation (B). The percentage of surviving cells is expressed as a lack of annexin V/PI staining determined by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

G-GSF inhibits calpain activation in neutrophils, upstream of caspase-3

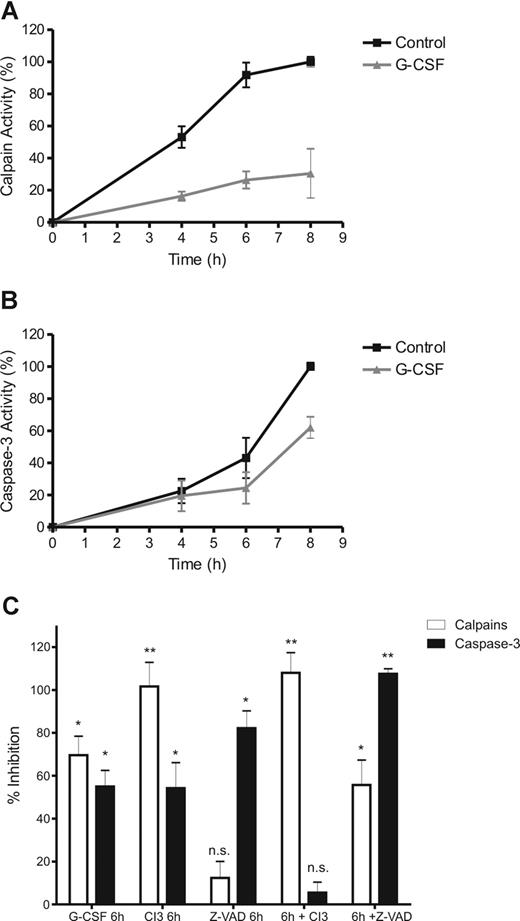

Calpains are cysteine proteases that are activated in a Ca2+-dependent manner and play an important role in neutrophil apoptosis.16,26 The observed critical rise in intracellular Ca2+ in neutrophils during apoptosis, prompted us to investigate the activation of calpains during neutrophil apoptosis.

Calpain and caspase-3 activities were measured in cell extracts, with fluorescently labeled peptides specific for each protease, although the calpain substrate we used for this study (calpain substrate II) does not distinguish between calpain-1 and -2 activities. Active proteases cleave the peptide whereupon the fluorescent group is released. As a result, the increase in fluorescence is indicative of the protease activity.

During incubation, both calpains and caspase-3 were found to be gradually activated in neutrophils (Figure 5A,B). Caspase-3 activity became detectable after 6 hours and did not reach peak levels in the 8 hours of the experiment, while calpain activity could already be measured from 4 hours onward reaching peak levels after 6 hours. Both proteases were significantly inhibited by G-CSF (Figure 5), although G-CSF had a more pronounced effect on calpains than on caspase-3 in the time frame of the experiment. Moreover, the specific calpain inhibitor 3 (CI3) inhibited calpain activity completely but also inhibited caspase-3 significantly in whole cells (Figure 5C). In contrast, the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD had no significant effect on calpain activity but inhibited caspase-3 to a similar extent as G-CSF.

G-CSF inhibits calpain activation, upstream of caspase-3. To determine calpain and caspase-3 activation during neutrophil apoptosis, cytosolic extracts of neutrophils, incubated in the presence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF and various inhibitors as indicated, were made at the indicated times (A,B) or after 8 hours (C). Protease activity was determined by incubating the samples in the presence of a fluorescent peptide, specific for either caspase-3 or calpains. After incubation, the increase in fluorescence was used as an indicator of the relative protease activity in the samples. To control for inhibitor/substrate specificity, the sample with the highest protease activity (the 8-hour control) was treated with 20 μM of the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD or 20 μM of the calpain inhibitor 3 (CI3). Activity is expressed as a relative to the control (8 hours, no inhibitors) as corrected for background activity (0 hours, no inhibitors). All data represent the mean (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (8 hours, no inhibitors) by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

G-CSF inhibits calpain activation, upstream of caspase-3. To determine calpain and caspase-3 activation during neutrophil apoptosis, cytosolic extracts of neutrophils, incubated in the presence of 10 ng/mL G-CSF and various inhibitors as indicated, were made at the indicated times (A,B) or after 8 hours (C). Protease activity was determined by incubating the samples in the presence of a fluorescent peptide, specific for either caspase-3 or calpains. After incubation, the increase in fluorescence was used as an indicator of the relative protease activity in the samples. To control for inhibitor/substrate specificity, the sample with the highest protease activity (the 8-hour control) was treated with 20 μM of the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD or 20 μM of the calpain inhibitor 3 (CI3). Activity is expressed as a relative to the control (8 hours, no inhibitors) as corrected for background activity (0 hours, no inhibitors). All data represent the mean (± SEM) of 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (8 hours, no inhibitors) by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

To verify specificity of the inhibitors, CI3 and z-VAD were added to samples with a high calpain/caspase-3 activity (ie the extract of untreated neutrophils, cultured for 8 hours). In these samples, CI3 completely inhibited calpain activity but it did not inhibit caspase-3. On the other hand, z-VAD completely inhibited caspase-3 activity in those samples but also prevented the cleavage of the calpain-specific fluorescent peptide to a significant degree. Apparently, z-VAD competes with the calpain peptide when added directly to a sample with active proteases, while it did not have this effect in intact cells. Because the calpain inhibitor completely blocked all activity measured with the calpain substrate, but had little effect on active caspases, we conclude that z-VAD might aspecifically inhibit calpains, rather than that the calpain substrate detects caspase activity. Therefore, we conclude that CI3 itself does not inhibit caspases, but inhibition of calpains leads to caspase-3 inhibition in whole cells. This demonstrates that calpains operate upstream of caspase-3 to regulate its activity.

G-CSF prevents the degradation of XIAP by calpains

Activation of the caspases downstream of mitochondrial permeabilization is controlled by the inhibitors of apoptosis, most notably the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP). XIAP has recently been identified as a target for calpains in neutrophils.16

XIAP degradation was analyzed on Western blots of whole cell extracts (Figure 6A). In fresh cells, only the full-length, 57-kDa form of XIAP was detectable. During incubation, the cleaved form of the protein became visible in the untreated cells after 8 hours. In G-CSF–treated cells, the cleaved form became detectable only after 20 hours. To see whether calpain inhibition could prevent XIAP degradation, neutrophils were incubated overnight with various inhibitors and controls as shown in Figure 6B. After overnight incubation, full-length XIAP was nearly completely degraded while 2 fragments appeared on the blot, one around 30 kDa and one around 20 kDa. Incubation with G-CSF delayed the cleavage of XIAP. Addition of cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/mL), a potent inhibitor of mRNA translation, to either control or G-CSF-treated cells had no effect on XIAP expression or degradation. However, CHX did have an effect on the delay of apoptosis induced by G-CSF after overnight incubation (Figure 6C). Inhibition of calpains by CI3 fully prevented the degradation of XIAP, whereas the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 had no effect, even though this inhibitor did delay neutrophil apoptosis (Figure 6B). The effect of MG132 on neutrophil apoptosis is mainly explained by stabilization of the antiapoptotic Bcl-1 family member Mcl-1, as previously demonstrated by Derouet et al41 (data not shown). None of the inhibitors by itself could completely prevent caspase-3 activation, as shown in Figure 6B, although caspase-3 activation was clearly reduced in G-CSF–, CI3- and z-VAD–treated cells.

G-CSF inhibits the degradation of XIAP in neutrophils. Neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of G-CSF, cycloheximide (CHX), G-CSF + CHX (G + CHX), the calpain inhibitor CI3 (20 μM), the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (50 μM), the caspase inhibitor z-VAD (20 μM) or the Ca2+chelator BAPTA (5 μM) for 16 hours. After incubation, whole-cell lysates were prepared, run on SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Western blot for XIAP expression (A,B).  indicates full-length XIAP (57 kDa) and its cleavage products (∼30 kDa and ∼20 kDa). The antibody is directed against a region at the C-terminal site of the protein, including the BIR3 domain. The blot is representative of 3 independent experiments. For panel B, the blot was reprobed to detect caspase-3. Survival was determined by annexin V staining on the flow cytometer (C). Data are expressed as a percentage (± SEM) of annexin V negative cells and represent 4 different experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (20 hours, no inhibitors) for all samples except G-CSF + CHX, which was compared with G-CSF, by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

indicates full-length XIAP (57 kDa) and its cleavage products (∼30 kDa and ∼20 kDa). The antibody is directed against a region at the C-terminal site of the protein, including the BIR3 domain. The blot is representative of 3 independent experiments. For panel B, the blot was reprobed to detect caspase-3. Survival was determined by annexin V staining on the flow cytometer (C). Data are expressed as a percentage (± SEM) of annexin V negative cells and represent 4 different experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (20 hours, no inhibitors) for all samples except G-CSF + CHX, which was compared with G-CSF, by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

G-CSF inhibits the degradation of XIAP in neutrophils. Neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of G-CSF, cycloheximide (CHX), G-CSF + CHX (G + CHX), the calpain inhibitor CI3 (20 μM), the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (50 μM), the caspase inhibitor z-VAD (20 μM) or the Ca2+chelator BAPTA (5 μM) for 16 hours. After incubation, whole-cell lysates were prepared, run on SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by Western blot for XIAP expression (A,B).  indicates full-length XIAP (57 kDa) and its cleavage products (∼30 kDa and ∼20 kDa). The antibody is directed against a region at the C-terminal site of the protein, including the BIR3 domain. The blot is representative of 3 independent experiments. For panel B, the blot was reprobed to detect caspase-3. Survival was determined by annexin V staining on the flow cytometer (C). Data are expressed as a percentage (± SEM) of annexin V negative cells and represent 4 different experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (20 hours, no inhibitors) for all samples except G-CSF + CHX, which was compared with G-CSF, by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

indicates full-length XIAP (57 kDa) and its cleavage products (∼30 kDa and ∼20 kDa). The antibody is directed against a region at the C-terminal site of the protein, including the BIR3 domain. The blot is representative of 3 independent experiments. For panel B, the blot was reprobed to detect caspase-3. Survival was determined by annexin V staining on the flow cytometer (C). Data are expressed as a percentage (± SEM) of annexin V negative cells and represent 4 different experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined relative to the control (20 hours, no inhibitors) for all samples except G-CSF + CHX, which was compared with G-CSF, by paired, 1-tailed Student t test. *P < .05, **P < .001, and n.s. (not significant), P > .05.

The caspase inhibitor z-VAD only had a partial effect on XIAP degradation. Some degradation did occur, but the lower cleavage product did not appear on blot. This could suggest that XIAP degradation is a 2-step process; the first step depending on calpain activity and the second on active caspases. Addition of 5 μM BAPTA-AM to the cells almost completely prevented the degradation of XIAP, thus confirming that the initiation of XIAP degradation indeed depends on intracellular Ca2+, which is an essential prerequisite for calpain activity.

Discussion

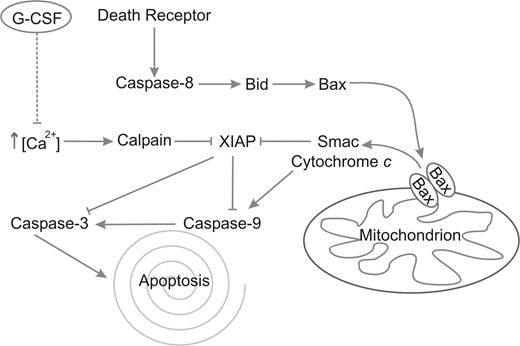

In this report, we demonstrate for the first time that G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis by the inhibition of calpain activity, which acts upstream of caspase-3. Our results indicate that spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis is accompanied by a gradual increase in intracellular free Ca2+ and suggests that neutrophil apoptosis proceeds at an accelerated pace after the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration has reached a certain threshold. G-CSF delays the influx of extracellular Ca2+, the subsequent activation of calpains and the downstream activation of caspase-3. Calpain inhibition completely prevents the degradation of XIAP in neutrophils. Apparently, the release of proapototic proteins from the mitochondria is not enough to overcome the inhibition of caspases by XIAP, because G-CSF hardly delayed the release of mitochondrial Smac. The fact that neutrophil mitochondria contain very little cytochrome c6,42 might explain this observed inefficiency of Smac to activate caspases, because cytochrome c normally activates the apoptosome, the complex wherein caspase-9 is activated. A schematic overview of these processes and the effect of G-CSF is given in Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the apoptotic pathways in neutrophils. Caspase-8 is activated after death receptor clustering and consequently activates Bid. Bid activates Bax, which multimerizes in the mitochondrial membrane, forming the permeability transition pore, through which Smac and cytochrome c are released. Smac competes with caspase-3 and -9 for binding with XIAP, thus removing its inhibitory effect from these caspases. Cytochrome c activates caspase-9 through the apoptosome. Finally, caspase-9 activates caspase-3, which executes the process of apoptosis. In parallel, Ca2+ levels rise spontaneously, which leads to the activation of calpains. The calpains cleave XIAP, resulting in a more rapid activation of caspases-9 and -3. G-CSF inhibits this rise in Ca2+, leading to inhibition of calpain activation, preventing the subsequent degradation of XIAP and causing a delay in the activation of caspases-9 and -3.

Schematic representation of the apoptotic pathways in neutrophils. Caspase-8 is activated after death receptor clustering and consequently activates Bid. Bid activates Bax, which multimerizes in the mitochondrial membrane, forming the permeability transition pore, through which Smac and cytochrome c are released. Smac competes with caspase-3 and -9 for binding with XIAP, thus removing its inhibitory effect from these caspases. Cytochrome c activates caspase-9 through the apoptosome. Finally, caspase-9 activates caspase-3, which executes the process of apoptosis. In parallel, Ca2+ levels rise spontaneously, which leads to the activation of calpains. The calpains cleave XIAP, resulting in a more rapid activation of caspases-9 and -3. G-CSF inhibits this rise in Ca2+, leading to inhibition of calpain activation, preventing the subsequent degradation of XIAP and causing a delay in the activation of caspases-9 and -3.

Calpain activation is regulated in several ways. During neutrophil activation, by bacterial ligands for example, Ca2+ levels also increase significantly.40 Although this may lead to temporal activation of calpains, it does not induce neutrophil apoptosis. Under these conditions, Smac and other proapoptotic factors are not released from the mitochondria and caspase-9 remains inactive. Moreover, XIAP is not the only target of calpains in neutrophils. Several isoforms of protein kinase C, for example, form another important target for calpains.43 After this kinase has been cleaved by calpains, the free catalytic subunit (protein kinase M, PKM) rapidly phosphorylates its targets. One of the results of PKC activation is the exposure of PS on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane via activation of the phospholipid scramblase responsible for an uneven distribution of PS over the inner and outer leaflet of the plasma membrane.44 Especially the PKC-δ isoform seems to be involved in neutrophil apoptosis. Whether this enzyme is regulated by caspase-3 or calpains in neutrophils, is not quite clear.45 Because we show that caspase-3 activation in neutrophils occurs downstream of calpain activation, we may have explained this apparent discrepancy in the literature. In addition, it appears that PKC-δ is involved in the stabilization and up-regulation of the Bcl-2 family member Bad, which also plays an important role in neutrophil apoptosis.46 Thus, calpains regulate several processes involved in neutrophil apoptosis, and their inactivation can delay the process at the different levels where the targets for calpain activity operate.

Similarly of course, it is not to be expected that inhibition of Ca2+ influx is the only way by which G-CSF inhibits neutrophil apoptosis and calpain activation. Probably, G-CSF also influences the gene expression pattern in mature neutrophils. Thus far, no detailed studies have been performed on gene expression profiling in mature neutrophils after G-CSF treatment. In the current study, protein translation inhibition by cycloheximide partially prevents the G-CSF–induced delay of neutrophil apoptosis. This suggests that gene expression plays an active role in this process. Further research is required to study the relevant effects of G-CSF on neutrophil gene expression.

As yet, we do not exactly know how G-CSF signaling prevents the spontaneous influx of Ca2+ during neutrophil apoptosis. The main intracellular store for Ca2+ is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It is well known that depletion of the Ca2+ store of the ER leads to an influx of extracellular Ca2+, the process of so-called store-operated Ca2+ influx.47 Ca2+ storage in the ER is mainly controlled by the interaction of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) with its receptor on the ER.48 An increase in free intracellular IP3 can thus lead to a release of Ca2+ from the ER, resulting in a brief rise of intracellular Ca2+. As a consequence of the depletion of Ca2+ from the ER, the store-operated channels for Ca2+ are opened in the plasma membrane, leading to a rapid, more steadfast, increase in intracellular free Ca2+. In recent years, it has become clear that the Bcl-2 family of proteins plays an important role in the control of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis49-51 by controlling the sensitivity of the IP3 receptor for its ligand. When the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, for example, associates with the IP3 receptor, it is less sensitive for IP3, while association of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bak increases the sensitivity of the receptor for IP3. Thus, expression and activation of Bcl-2 family members control the influx of extracellular Ca2+. Neutrophils do not express Bcl-2, but, instead, express the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, and Bfl-1.52-54 Bfl-1 has been shown to associate with Bak and to control its activity.55 In addition, G-CSF has been shown to increase the expression of Bfl-1 in neutrophils.56 Therefore, it would not seem unlikely that G-CSF controls the influx of extracellular Ca2+ via control of Bfl-1, but further research has to be done to clarify this link in neutrophils.

In conclusion, we show that G-CSF controls neutrophil apoptosis via control of calpain activity. Thus, we shed new light on the actions of this clinically relevant cytokine in the control of neutrophil homeostasis. In addition, we emphasize the importance of the control of Ca2+ homeostasis in the process of apoptosis. Further research is required to elucidate the exact mechanism of Ca2+ control by G-CSF.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Prof Roos for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, Den Haag, The Netherlands (NWO-Vidi scheme 917.46.319).

Authorship

Contribution: B.J.v.R. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.D. and V.G. helped perform parts of the research; and T.K.v.d.B. and T.W.K. supervised the project and reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bram J. van Raam, Department of Blood Cell Research, Phagocyte Laboratory, Sanquin Research and Landsteiner Laboratory, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: b.j.vanraam@gmail.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal