Abstract

An effective response to extreme hematopoietic stress requires an extreme elevation in hematopoiesis and preservation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). These diametrically opposed processes are likely to be regulated by genes that mediate cellular adaptation to physiologic stress. Herein, we show that heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), the inducible isozyme of heme degradation, is a key regulator of these processes. Mice lacking one allele of HO-1 (HO-1+/−) showed accelerated hematopoietic recovery from myelotoxic injury, and HO-1+/− HSCs repopulated lethally irradiated recipients with more rapid kinetics. However, HO-1+/− HSCs were ineffective in radioprotection and serial repopulation of myeloablated recipients. Perturbations in key stem cell regulators were observed in HO-1+/− HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors (HPCs), which may explain the disrupted response of HO-1+/− HPCs and HPCs to acute stress. Control of stem cell stress response by HO-1 presents opportunities for metabolic manipulation of stem cell–based therapies.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the only cells capable of producing all hematopoietic lineages. Preserving this population is crucial for sustained lifelong hematopoiesis, especially in the face of hematopoietic stress, where the recruitment of HSCs into the cell cycle to differentiate and produce mature blood cells intensifies to meet the immediate challenge.1,2 Cell-cycle regulators such as p21Waf-1/Cip-1 (p21), the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, restrict the entry of HSCs into the cell cycle to proliferate and results inexorably move toward terminal differentiation under stress conditions. In the absence of such a restriction, HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) uncontrollably proliferate and differentiate, leading to premature depletion and exhaustion of the stem cell reserve.2

Heme promotes the proliferation and differentiation of HPCs3 and stimulates hematopoiesis.3-5 The amount of heme generated daily in the body via the breakdown of hemoglobin is significant and, in cases of severe hemolysis after irradiation and bone marrow (BM) transplantation, may increase to levels that lead to cellular damage.6 The degradation of heme is catalyzed by heme oxygenase (HO), leading to the equimolar production of iron, biliverdin (subsequently converted to bilirubin), and carbon monoxide (CO). Biliverdin and bilirubin are potent antioxidants7 and CO potentially regulates numerous cellular functions, including proliferation/differentiation, via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) signaling pathways8 and p21.9 HO-1, encoded by the Hmox1 gene, is the stress-inducible isozyme of HO and expressed at high levels in the spleen and BM.5 Genetically engineered HO-1–null (HO-1−/−) mice10,11 and one rare human case of HO-1 deficiency12,13 have abnormal levels of both plasma heme and its products5 and also a vulnerability to oxidative stress. The combination of the stress-inducible and antioxidative nature of HO-1, the role of CO in activating signaling pathways, and the importance of p38MAPK14,15 and p212 in regulating stem cell function, point toward HO-1 being a critical regulator of the stress response in HSCs and HPCs via controlling the level of its substrates (heme) and bioactive products (biliverdin/bilirubin and CO), especially under stress conditions.

Methods

Mice

FVB/NJ recipients (8-12 weeks old) were obtained from the Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Creation of the luciferase transgenic mouse line (FVB.luc+) was described previously.16,17 FVB.Cg-Tg(GFP)5Nagy mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred with FVB.luc+ mice. HO-1−/− mice10 were generously provided by Dr Phyllis A. Dennery (Philadelphia, PA) and backcrossed to an FVB/N background for at least 6 generations to generate FVB/N HO-1+/− mice, which then were bred to maintain the congeneic strain and to generate HO-1+/−, luc+ HO-1+/−, and GFP+HO-1+/−. Genotyping was done by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All mice used were littermates or age-matched and housed in the Research Animal Facility at Stanford University. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Stanford University.

HO activity

HO activity in Lin− BM cells (∼5 × 106) was determined through measurements of CO as described previously.18 In brief, cell sonicates were incubated with equal (20 μL) volumes of NADPH (4.5 μmol/L) and methemalbumin (50 μmol/L heme/11.2 μmol/L bovine serum albumin) for 15 minutes at 37°C in 2 mL CO-purged septum-sealed amber vials. The amount of CO in the vial headspace was determined by gas chromatography with a reduction gas detector (RGA2; Trace Analytical, Menlo Park, CA) operated at 270°C. HO activity was expressed as nanomoles of CO per hour per milligram of protein.

Blood cell parameters

Complete blood counts were performed in the Diagnostic Laboratory of the Department of Comparative Medicine at Stanford University according to standard laboratory protocols.

Isolation and transplantation of BM cells and HSCs

BM cells were isolated as described previously.16 Isolated BM cell suspensions were then filtered through a nylon mesh before staining for HSCs. Donor c-kit+Thy-1.1loLin−Sca-1+ (KTLS) HSCs were isolated by double fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of c-kit–enriched BM from luc+ or luc+ GFP+ transgenic mice, based on previously defined reactivity for particular cell surface markers (including lineage markers, c-kit, Thy1.1, and Sca-1). Cells were then transferred into irradiated recipient mice by tail-vein injections.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

Imaging of mice for whole-body bioluminescent signals was conducted as described previously.16,19 In brief, an aqueous solution of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg intraperitoneally; Caliper Life Sciences, Alameda, CA) was injected 10 minutes before imaging and the animals were anesthetized with 1.5%-2% isoflurane and placed in the imaging chamber where a Gas Anesthesia System is housed to deliver isoflurane through a 5-port anesthesia manifold. Imaging was performed using an IVIS200 (Caliper Life Sciences). Data were analyzed with Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences).

In vivo assay for tracking cell divisions

BM cells were labeled with 1 μmol/L 5-(and 6-)-carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described.20,21 CFSE-labeled HO-1+/+ and HO-1+/− BM cells (108) were injected into lethally irradiated mice. Two days after transplantation, recipient BM cells were stained with the antibody cocktail for lineage markers and Sca-1. The LSR Model 1A Analyzer was used for data acquisition, and FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR) was used for analysis of cell proliferation.

Serial transplantation analysis

Five thousand luc+ KTLS cells were collected from HO-1+/− and wild-type mice and then transplanted into lethally irradiated primary recipients. BLI was used to monitor the progression of hematopoietic reconstitution. Twelve weeks later, primary recipients were killed and one-fifth of the whole BM equivalents were transferred to lethally irradiated secondary recipients, and this was repeated twice for a total of 4 transplants. Serial BM transplantation was also performed using a lower number of BM cells (2 × 106/host) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a second donor marker to allow flow cytometric analysis of chimerism.

Real-time reverse-transcription PCR

Lin− BM cells and FACS KTLS HSCs of these mice were purified and the copy numbers of HO-1, HO-2, and relative value of p21 mRNA were detected using real-time reverse-transcription PCR as described previously.22 p21 primers were: forward, 5′-CTGTCTTGCACTCTGGTGTCTGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-TTTTCTCTTGCAGAAGACCAATCTG-3′. Copy numbers of HO-1, HO-2, and p21 mRNA for each sample were calculated from a standard curve and then normalized to β-actin levels.

Flow cytometric analysis of levels of HO-1 and p21 expression and p38MAPK phosphorylation

Whole BM cells were stained with antibodies against SLAM family members CD150, CD48 (Cy7PE- or phycoerythrin [PE]-conjugated, respectively; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), and CD244 (biotinylated antibody; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), subsequently stained with streptavidin-allophycocyanin (APC)/Cy7 (BioLegend). Then antibodies against HO-1 (FITC-conjugated; StressGen Bioreagents, Victoria, BC), phosphorylated p38MAPK23 (APC-conjugated; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or p21 (APC-conjugated; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) were used for intracellular staining, after fixation and permeabilization of cells using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences). Phenotypically defined HSCs (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPPs (CD244+CD48−CD150−), and more restricted progenitor (CD48+CD244+CD150−) populations were distinguished by the gating strategy as described previously.24 Analysis of BrdU incorporation was performed using BrdU Flow Kits (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses

For comparison of experimental groups, analysis of variance was first performed for each set of experiments to determine statistically significant differences between the experimental groups at the P = .05 and .01 levels (2-tailed). Numbers of animals used and P values are listed in the legend of each figure. In some experiments, one-tailed t tests were used to assess differences between the experimental groups, as indicated.

Results

In this study, we examined HO-1 heterozygous knockout (HO-1+/−), rather than HO-1−/−, mice and cells, for 2 reasons: (1) conditions of decreased levels, rather than complete lack, of HO-1 expression are more common in humans and therefore more clinically relevant; and (2) HO-1−/− mice exhibit partial prenatal lethality10 leading to an extremely limited availability of these animals. In more than 800 live births from HO-1+/− × HO-1+/− breeding over a 2-year period, only 7 HO-1−/− mice were viable, a survival rate (3%) that is similar to that reported by others (personal communications with Drs A. M. Choi of the University of Pittsburgh [Pittsburgh, PA], and E. G. Nabel and M. Olive of the National Institutes of Health [Bethesda, MD]).

Differential expression of HO-1 and cell-cycle regulators in hematopoietic subsets in the absence of stress

Lineage-depleted (Lin−) BM cells, a population enriched for HPCs, from HO-1+/− mice at steady state had lower levels of total HO enzyme activity and HO-1 mRNA compared with cells from HO-1 wild-type (HO-1+/+) animals (Figure S1A,B, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), whereas mRNA levels of HO-2, the constitutive HO isozyme, were similar in these cells as expected (Figure S1C). Intracellular staining demonstrated that HO-1 protein levels in HSCs and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) were lower than levels in restricted progenitors for both HO-1+/+ and HO-1+/− genotypes (Figure S1D,E). However, compared between genotypes, protein levels were significantly lower in HO-1+/− MPPs and more restricted progenitors, relative to HO-1+/+ cells (n = 6, P < .05, respectively) (Figure 1A). Comparable levels of HO-1 protein were however found in HO-1+/+ and HO-1+/− whole BM cells and HSCs. These findings suggest that HO-1 is differentially expressed during hematopoietic development and that lack of one allele of HO-1 gene significantly affects the levels of HO-1 protein in progenitors.

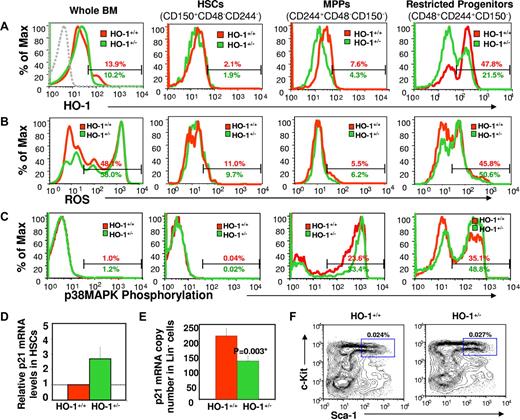

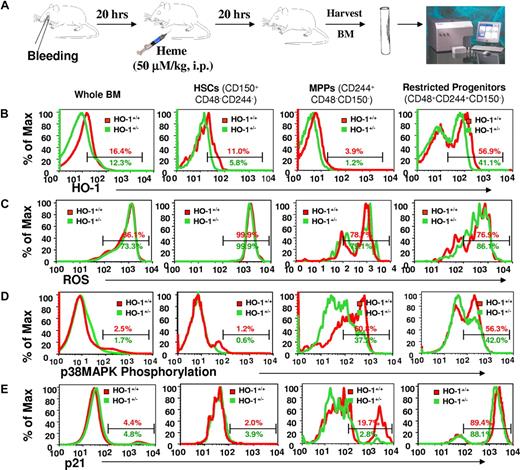

Differential expression profiles of HO-1 during different stages of hematopoietic development and changes in levels of intracellular ROS, p38MAPK phosphorylation, and p21 expression in HO-1–deficient mice under steady-state conditions. Representative FACS plots of the levels of intracellular HO-1 protein (A), ROS (B), and p38MAPK phosphorylation (C) in whole BM, HSCs, MPPs, and restricted progenitors. BM cells from HO-1+/+ and HO-1+/− mice (n = 6 for each group) were harvested and stained with antibodies for phenotypically defined HSC (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPP (CD244+CD48−CD150−), and more restricted progenitor (CD48+CD244+CD150−) populations. To assess intracellular ROS levels, stained cells were incubated with DCF, a fluorescent dye for detection of intracellular ROS. For measurement of intracellular HO-1 protein, and p38MAPK phosphorylation, stained cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with antibodies against HO-1, and phosphorylated p38MAPK, respectively. The broken line in the first panel of Figure 1A is the isotope control with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse IgG antibody. Values are the mean percentages indicating the gated proportion of cells. Please note that some of the histograms were skewed to the left due to the number of events on the y-axis. p21 expression was assessed by real-time PCR in HO-1–deficient cells. KTLS HSCs or Lin− BM cells were isolated from HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice at steady state, total RNA was prepared from these cells for p21 mRNA quantitation using real-time PCR. p21 mRNA levels were accumulated in purified KTLS HSCs (displayed is an average fold change of four experiments) (D) but decreased in HO-1+/− Lin− BM cells (mean ± SD, n = 4) (E). The frequency of KTLS HSCs was analyzed from nucleated BM cells and are displayed as the mean (n = 3) (F).

Differential expression profiles of HO-1 during different stages of hematopoietic development and changes in levels of intracellular ROS, p38MAPK phosphorylation, and p21 expression in HO-1–deficient mice under steady-state conditions. Representative FACS plots of the levels of intracellular HO-1 protein (A), ROS (B), and p38MAPK phosphorylation (C) in whole BM, HSCs, MPPs, and restricted progenitors. BM cells from HO-1+/+ and HO-1+/− mice (n = 6 for each group) were harvested and stained with antibodies for phenotypically defined HSC (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPP (CD244+CD48−CD150−), and more restricted progenitor (CD48+CD244+CD150−) populations. To assess intracellular ROS levels, stained cells were incubated with DCF, a fluorescent dye for detection of intracellular ROS. For measurement of intracellular HO-1 protein, and p38MAPK phosphorylation, stained cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then stained with antibodies against HO-1, and phosphorylated p38MAPK, respectively. The broken line in the first panel of Figure 1A is the isotope control with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse IgG antibody. Values are the mean percentages indicating the gated proportion of cells. Please note that some of the histograms were skewed to the left due to the number of events on the y-axis. p21 expression was assessed by real-time PCR in HO-1–deficient cells. KTLS HSCs or Lin− BM cells were isolated from HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice at steady state, total RNA was prepared from these cells for p21 mRNA quantitation using real-time PCR. p21 mRNA levels were accumulated in purified KTLS HSCs (displayed is an average fold change of four experiments) (D) but decreased in HO-1+/− Lin− BM cells (mean ± SD, n = 4) (E). The frequency of KTLS HSCs was analyzed from nucleated BM cells and are displayed as the mean (n = 3) (F).

In contrast to differential HO-1 expression, HO-1+/− whole BM cells, but not phenotypically defined HSCs or HPCs, showed higher levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) compared with HO-1+/+ cells (n = 4, P = .005; Figure 1B). The levels of intracellular ROS in HO-1+/− restricted progenitors were slightly, but not statistically significant, higher than that in HO-1+/+ cells. These findings suggest that an increase in intracellular ROS in HO-1–deficient cells is outside the HSC compartment. However, activation of p38MAPK (Figure 1C), a sensor of ROS23 that negatively regulates cell proliferation and stem cell function,14,15 was increased in MPPs and more restricted progenitors (n = 6, P < .05, respectively).

p21 is believed to be induced by the heme catabolic product CO 9,25,26 and to dominantly regulate the entry of HSCs into the cell cycle.2 and has been reported to be down-regulated in HO-1−/− cells.27 However, we found that p21 mRNA levels were approximately 2.8-fold higher in HO-1+/− HSCs than that of in wild-type cells (Figure 1D), but 50% lower in Lin− cells (n = 4, P = .003) (Figure 1E). Despite these alterations in HO-1 and cell-cycle regulators, there were no differences between HO-1+/− and HO-1+/+ mice in their frequency of HSCs (Figures S1F and S2A) and HPCs (Figure S2B), BrdU incorporation in hematopoietic subsets (Figure S2C), and peripheral blood cell parameters under steady-state conditions (data not shown). These findings suggest that the turnover of all lineage cells of steady-state animals was not increased.

Accelerated hematopoietic response to acute stress in HO-1 deficiency

Normal hematopoiesis of HO-1+/− mice in steady state may not be surprising because HO-1 is a stress response gene, and its effects might not be apparent in the absence of stress. We therefore investigated the effect of HO-1 on the stress response of HSCs and HPCs. HO-1+/− and wild-type mice were first given a single dose of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; 150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) to eliminate mitotic cells and cause hemolysis and leucopenia. Hematopoietic recovery was evaluated by measuring a range of blood parameters. 5-FU–treated HO-1+/− mice recovered more rapidly relative to wild-type mice, with the numbers of leukocytes approximately 2-fold greater at days 13 and 20 (n = 4, P < .033, respectively; Figure 2A), and reticulocyte approximately 50% higher at day 17 (n = 9, P = .032) (Figure S3A). Hemoglobin levels were not significantly different (Figure S3B).

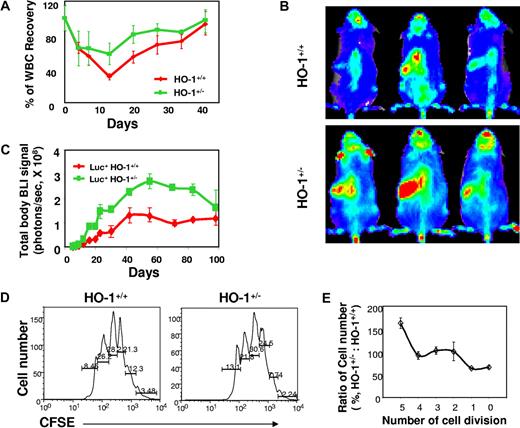

Accelerated hematopoietic recovery in HO-1+/− mice treated with 5-FU and reconstitution in recipients of large numbers of HO-1+/− BM cells. (A) Leukocyte counts of HO-1+/− mice after myelotoxic injury. HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice (n = 10) were treated with a single dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg intraperitoneally), and leukocyte counts in the peripheral blood were performed at different time points after treatment and are shown as a mean (± SD) percentage of normal leukocyte count. (B,C) Hematopoietic engraftment from HO-1–deficient BM cells in lethally irradiated recipients. BM cells (5 × 106) from luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 4) and hematopoietic engraftment was monitored by BLI. Representative BLI images of the recipients of luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ cells at day 18 are displayed at the same scale (B). Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution, as measured by whole-body bioluminescent intensity (mean ± SD, photons/s) over time (C). (D) Representative FACS plots and (E) relative trend of CFSE+Lin−Sca-1+ cell distribution versus number of cell division in vivo. Nucleated BM cells (1 × 107) from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were labeled by CFSE (1 μM) and transferred into lethally irradiated recipients. Cells recovered from the BM of the recipients 48 hours after transfer were pooled (3 mice/group) and costained by antibodies against lineage markers and Sca-1. The number of cell divisions and cell distribution were analyzed by CFSE intensity after gating for the Lin−Sca-1+ population. Values are absolute (D) or relative (E) mean percentages (n = 4) of cells undergoing different numbers of cell divisions from 2 different experiments.

Accelerated hematopoietic recovery in HO-1+/− mice treated with 5-FU and reconstitution in recipients of large numbers of HO-1+/− BM cells. (A) Leukocyte counts of HO-1+/− mice after myelotoxic injury. HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice (n = 10) were treated with a single dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg intraperitoneally), and leukocyte counts in the peripheral blood were performed at different time points after treatment and are shown as a mean (± SD) percentage of normal leukocyte count. (B,C) Hematopoietic engraftment from HO-1–deficient BM cells in lethally irradiated recipients. BM cells (5 × 106) from luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 4) and hematopoietic engraftment was monitored by BLI. Representative BLI images of the recipients of luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ cells at day 18 are displayed at the same scale (B). Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution, as measured by whole-body bioluminescent intensity (mean ± SD, photons/s) over time (C). (D) Representative FACS plots and (E) relative trend of CFSE+Lin−Sca-1+ cell distribution versus number of cell division in vivo. Nucleated BM cells (1 × 107) from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were labeled by CFSE (1 μM) and transferred into lethally irradiated recipients. Cells recovered from the BM of the recipients 48 hours after transfer were pooled (3 mice/group) and costained by antibodies against lineage markers and Sca-1. The number of cell divisions and cell distribution were analyzed by CFSE intensity after gating for the Lin−Sca-1+ population. Values are absolute (D) or relative (E) mean percentages (n = 4) of cells undergoing different numbers of cell divisions from 2 different experiments.

Similar to 5-FU administration, total body irradiation, as used in BM transplantation, also causes hemolysis and high levels of free heme. Under these conditions, the proliferative demand on transplanted HSCs and HPCs is tremendous as they attempt to reconstitute the ablated hematopoietic system. To evaluate the impact of HO-1 deficiency on HSC reconstitution potential, we backcrossed HO-1+/− mice with luciferase transgenic mice (luc+ mice, β-actin–driven luciferase)16 to acquire luciferase expression in hematopoietic cells. This strategy enables noninvasive assessment of hematopoietic reconstitution using in vivo BLI to visualize early events of engraftment and to quantitate total whole-body signals as an index of donor-derived hematopoiesis and engraftment.16 After transfer of 5 × 106 luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ whole BM cells into lethally irradiated congeneic recipients, bioluminescent imaging (BLI) revealed a 3-fold increase in the overall bioluminescent signals in recipients of luc+HO-1+/− cells compared with those receiving luc+HO-1+/+ cells (n = 4, P < .01 at nearly all time points, except at day 98; Figure 2B,C). Increased signal intensities were detected as early as day 4 after transplantation. At 3 to 4 weeks after transplantation, splenic weight and cellularity in recipients of the HO-1+/− cells were also greater (Figure S4A-C). It is noteworthy that, after peaking (at approximately 56 days), overall bioluminescent intensities in recipients of HO-1–deficient BM cells began to decrease to levels observed in mice that received HO-1+/+ cells (Figure 2C).

These findings were confirmed by quantitative assessment of hematopoietic reconstitution from defined hematopoietic lineages constitutively expressing GFP+,28 which served as a second donor marker to track hematopoietic reconstitution. Recipients of HO-1+/− GFP+ BM HSCs exhibited enhanced reconstitution of GFP+ hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood, spleen, and BM at days 8, 12, and 20 (n = 4, P < .01, Figure S4D) and at day 56 (n = 4, P = .006, Figure S4E), indicating that the GFP+HO-1+/− BM HSCs were hyperresponsive after transplantation at early time points. At later time points (14 and 20 weeks, data not shown), however, there were no apparent differences in overall hematopoiesis between recipients of HO-1–deficient and wild-type cells, a pattern also seen with BLI. Taken together, data from both myelotoxic injury and BM transplantation models suggest that HO-1 deficiency leads to a short-term, accelerated hematopoietic recovery of HO-1+/− mice from myelotoxic injury and reconstitution after transfer of HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs.

Accelerated hematopoietic response to stress in HO-1 deficiency suggested a possibility of a more rapid cell cycling of HSCs and/or HPCs when HO-1 is deficient. To evaluate this possibility, we determined the number of cell divisions in defined donor cell populations isolated from irradiated recipients. Donor BM cells were labeled with CFSE before transfer. The intensity of dye was used as an indicator of the number of cell divisions for each cell population.20,21 We analyzed the number of in vivo cell divisions for Lin−Sca-1+ cells, a phenotypically defined population enriched for HSCs and HPCs, recovered from the BM and spleens of recipients at 48 hours after transplantation. HO-1+/− Lin−Sca-1+ cells underwent the same number of cell divisions as the wild-type cells (Figure 2D,E); however, more HO-1+/− Lin−Sca-1+ cells were extensively dividing and their percentage in more than 5 cell divisions was approximately 1.5- to 1.7-fold greater compared with those receiving wild-type cells (n = 4, P = .041; Figure 2D,E). These data indicate that proliferation of HO-1+/− HSCs and/or HPCs was slightly accelerated in response to hematopoietic stress.

Ineffective response of HO-1+/− HSCs to acute stress

Based on the observed accelerated response of HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs to stress, one might predict that these cells would more effectively protect recipients from radiation-induced hematopoietic failure. It is also possible that in the absence of regulation, HSCs (and probably HPCs) rush into the cell cycle and differentiate, leading to premature depletion of their reserves and eventually to hematopoietic failure under conditions of stress.2 To test this possibility, we transplanted a small number of BM cells (2 × 105 cells/recipient, a subdose for complete radioprotection) into lethally irradiated recipients. HO-1+/− BM cells showed a dramatically compromised ability to rescue these recipients; all recipients (n = 30) succumbed to hematopoietic failure before day 28. In contrast, survival rate in mice (n = 30) that received HO-1+/+ BM cells was 75% (Figure 3A). Increasing the number of transplanted BM cells to 6 × 105, twice the radio-protective dose, also failed to provide full radioprotection (Figure S5A).

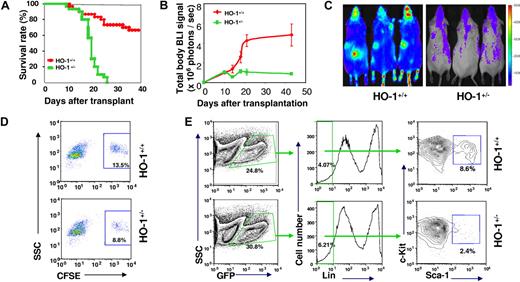

Ineffectiveness of primitive HO-1+/− cells in radioprotection of lethally irradiated recipients and in preservation of their adoptive reserve. (A) Kaplan-Meier plots showing a defect of HO-1+/− BM cells in providing radioprotection. BM cells (2 × 105) from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 30) and survival rates were compared. (B,C) Assessment of short-term hematopoiesis from limited number of HO-1+/− BM cells. BM (2 × 105) cells from either luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred together with 2 × 106 unlabeled BM cells into lethally irradiated recipients and overall hematopoiesis was visualized over time by BLI. (B) Representative BLI images of the recipients at day 22 displayed at the same scale. (C) Kinetics of hematopoietic reconstitution from luc+ BM cells. (D,E) Frequency of HO-1+/− Lin−Sca-1 + and LSK populations in hematopoietic cells recovered from recipients of 107 nucleated BM cells from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice. CFSE-labeled nucleated BM cells were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients. Forty-eight hours after transfer, cells were recovered from BM of the recipients, pooled (3 mice/group), and costained by antibodies to lineage markers and Sca-1. The frequency of CFSE+ Lin− Sca-1+ cells was analyzed between groups. Values are means of 2 experiments (D). In related experiments, a decreased frequency of the LSK population in hematopoietic tissues of recipients was observed. Because the levels of c-Kit expression are lower after transplantation and return to normal by approximately 2 weeks21 (A.J.W., unpublished observations), it enabled us to analyze LSK population in cells recovered from recipients. BM cells (2 × 106) from GFP+HO-1+/− or GFP+HO-1+/+ mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 3) and donor-derived cells were then recovered for assessment of either donor-derived (GFP+) LSK population at day 20 after transfer (E).

Ineffectiveness of primitive HO-1+/− cells in radioprotection of lethally irradiated recipients and in preservation of their adoptive reserve. (A) Kaplan-Meier plots showing a defect of HO-1+/− BM cells in providing radioprotection. BM cells (2 × 105) from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 30) and survival rates were compared. (B,C) Assessment of short-term hematopoiesis from limited number of HO-1+/− BM cells. BM (2 × 105) cells from either luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred together with 2 × 106 unlabeled BM cells into lethally irradiated recipients and overall hematopoiesis was visualized over time by BLI. (B) Representative BLI images of the recipients at day 22 displayed at the same scale. (C) Kinetics of hematopoietic reconstitution from luc+ BM cells. (D,E) Frequency of HO-1+/− Lin−Sca-1 + and LSK populations in hematopoietic cells recovered from recipients of 107 nucleated BM cells from either HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice. CFSE-labeled nucleated BM cells were transferred into lethally irradiated recipients. Forty-eight hours after transfer, cells were recovered from BM of the recipients, pooled (3 mice/group), and costained by antibodies to lineage markers and Sca-1. The frequency of CFSE+ Lin− Sca-1+ cells was analyzed between groups. Values are means of 2 experiments (D). In related experiments, a decreased frequency of the LSK population in hematopoietic tissues of recipients was observed. Because the levels of c-Kit expression are lower after transplantation and return to normal by approximately 2 weeks21 (A.J.W., unpublished observations), it enabled us to analyze LSK population in cells recovered from recipients. BM cells (2 × 106) from GFP+HO-1+/− or GFP+HO-1+/+ mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients (n = 3) and donor-derived cells were then recovered for assessment of either donor-derived (GFP+) LSK population at day 20 after transfer (E).

As an in vivo guide to track hematopoietic engraftment from a subdose of BM cells, 2 × 105 luc+HO-1+/− BM cells were transferred into each lethally irradiated recipient along with 1 × 106 luc− helper BM cells that protected all animals from hematopoietic death over the duration of the experiment. BLI revealed an early plateau of reconstitution from luc+HO-1+/− BM cells with a slightly higher BLI signal (n = 5, P = .027) at day 10, compared with a later peak from luc+HO-1+/+ BM cells at approximately day 42 with significantly higher levels of BLI signals (n = 5, P < .01; Figure 3B,C). These observations suggest that HO-1+/− BM cells were profoundly defective in providing radioprotection, although they exhibited equivalent homing properties (Figures S5B-D) and were able to compete with HO-1+/+ HSCs for engraftment (Figure S5E) compared with wild-type cells. The accelerated response of HO-1+/− BM cells might transiently enhance hematopoiesis immediately after transplantation. However, the accelerated hematopoiesis was unsustainable and ineffective in protecting lethally irradiated recipients.

To directly assess the ability of HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs to sustain their reserve in stress conditions, we determined the numbers of Lin−Sca-1+ cells that could be recovered from BM and spleen of the recipients after 48 hours and found that there were approximately 40% fewer HO-1+/− than HO-1+/+ cells (Figure 3D). There were also approximately 50% fewer Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells (Figure 3E) at day 20 and approximately 50% fewer erythroid progenitors at day 15 (Figure S6) in recipients of HO-1+/− BM cells (GFP used as a donor marker). Thus, the decreases in HO-1+/− HPC compartments after acute stress might have accounted for the observed ineffective and unsustainable stress hematopoiesis.

Accelerated exhaustion of HO-1+/−HSCs

The decreases in HO-1+/− HPC compartments after transplantation with limited cell numbers raises the question of whether HO-1+/− HSCs are capable of sustaining lifelong hematopoiesis even when their reserve is large. If not, the hematopoietic exhaustion that is provoked by long-term hematopoietic stress may be exacerbated by HO-1 deficiency. To address these questions, we serially transplanted BM cells from animals that received a large number of luc+HO-1+/− KTLS HSCs (5000/recipient) into lethally irradiated mice (Figure 4A). Similar to previous observations, the primary recipients exhibited 6-fold levels of overall bioluminescent signal compared with mice receiving wild-type HSCs (n = 10, P < .01 for each time point; Figure 4B). Dissection of recipients at early time points after transplantation revealed larger hypercellular spleens in mice that received HO-1+/− HSCs. Higher levels of overall bioluminescent signals in the recipients of luc+HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs continued in the secondary transplants (n = 10, P < .01 for each time point); however, the difference between the groups began to diminish after tertiary transplantations. In quaternary transplants, bioluminescent signals from recipients of the HO-1+/− cells was decreased dramatically, after a transient peak in the first 4 weeks, to levels that were lower than those of recipients of the HO-1+/+ cells (n = 10, P < .01; Figure 4B). Whole-body bioluminescence signals in recipients of HO-1+/− and wild-type cells during the serial transplantations demonstrated a dramatic reversal, from 6-fold in the primary recipients to approximately 0.2-fold in the quaternary recipients (Figure S7). When GFP-expressing cells were used, quantitative analysis by flow cytometry also revealed a reversal in the number of HO-1+/− cell-derived leukocytes: greater in the primary transplant and smaller in the secondary compared with that of HO-1+/+ cells, respectively (Figure 4C,D). Although fewer HSCs (GFP+) were used in this experiment for serial BM transplantation, the reversal occurred more quickly, and the pattern was similar. In addition, the frequency of the GFP+KTLS HSCs in the secondary recipients being slightly less in recipients of HO-1+/− BM cells compared with that receiving HO-1+/+ cells (0.0025% vs 0.0041%, n = 4, P = .048; Figure 4E).

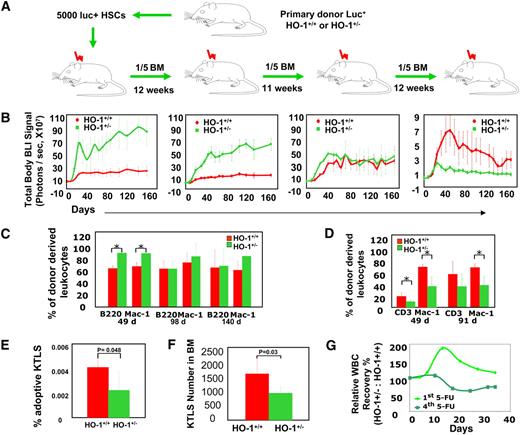

Accelerated exhaustion of HO-1+/− HSCs provoked by stress of serial transplantation or repeated myelotoxic injuries in HO-1 deficiency. (A) Experimental design. Five thousand HSCs from luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated primary recipients. Twelve weeks later, one-fifth of the BM recovered from these recipients was transplanted into secondary recipients, and so on, for a total of 4 transplantations. (B) Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution of serially transplanted recipients was measured by BLI. Values are shown as mean (± SD) whole-body BLI intensities (n = 10 for each group). (C,D) Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution from serially transplanted GFP+HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ BM cells. Hematopoietic contribution from 2 × 106 BM cells to peripheral myeloid (Mac-1+) and lymphoid (CD3+ or B220+) subsets was analyzed by flow cytometry at days 49 (n = 6, P < .017), 98 (n = 5, P > .22), and 140 (n = 5, P > .35) in the primary recipients (C) and at days 49 (n = 5, P = .028) and 91 (n = 8, P = .0005) in the secondary recipients (D). (E) The adoptive (GFP+) HO-1+/− KTLS HSC compartment assessed at 12 weeks after secondary transplantation. Values displayed are mean (± SD) of 4 samples and P value is one-tailed. (F,G) Repeated myelotoxic injuries and accelerated exhaustion of HO-1+/− HSCs. HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were treated with doses of 5-FU (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) at weeks 1, 2, and 5, respectively. The frequency of KTLS HSC population in nucleated BM cells was analyzed at week 18, and mean (± SD); (n = 4) of KTLS numbers in Lin−Thy1.1lo cells is displayed. P value is 1-tailed (F). In a separate experiment, mice were injected a fourth dose of 5-FU, followed by leukocyte counts in peripheral blood, and their relative WBC counts were compared with that of mice receiving a single dose of 5-FU. Values are mean (± SD) WBC count of HO-1+/− mice relative to that of HO-1+/+ after 4th dose (n = 6) of 5-FU versus that of 1st dose (n = 4) (G).

Accelerated exhaustion of HO-1+/− HSCs provoked by stress of serial transplantation or repeated myelotoxic injuries in HO-1 deficiency. (A) Experimental design. Five thousand HSCs from luc+HO-1+/− or luc+HO-1+/+ mice were transferred into lethally irradiated primary recipients. Twelve weeks later, one-fifth of the BM recovered from these recipients was transplanted into secondary recipients, and so on, for a total of 4 transplantations. (B) Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution of serially transplanted recipients was measured by BLI. Values are shown as mean (± SD) whole-body BLI intensities (n = 10 for each group). (C,D) Time course of hematopoietic reconstitution from serially transplanted GFP+HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ BM cells. Hematopoietic contribution from 2 × 106 BM cells to peripheral myeloid (Mac-1+) and lymphoid (CD3+ or B220+) subsets was analyzed by flow cytometry at days 49 (n = 6, P < .017), 98 (n = 5, P > .22), and 140 (n = 5, P > .35) in the primary recipients (C) and at days 49 (n = 5, P = .028) and 91 (n = 8, P = .0005) in the secondary recipients (D). (E) The adoptive (GFP+) HO-1+/− KTLS HSC compartment assessed at 12 weeks after secondary transplantation. Values displayed are mean (± SD) of 4 samples and P value is one-tailed. (F,G) Repeated myelotoxic injuries and accelerated exhaustion of HO-1+/− HSCs. HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice were treated with doses of 5-FU (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) at weeks 1, 2, and 5, respectively. The frequency of KTLS HSC population in nucleated BM cells was analyzed at week 18, and mean (± SD); (n = 4) of KTLS numbers in Lin−Thy1.1lo cells is displayed. P value is 1-tailed (F). In a separate experiment, mice were injected a fourth dose of 5-FU, followed by leukocyte counts in peripheral blood, and their relative WBC counts were compared with that of mice receiving a single dose of 5-FU. Values are mean (± SD) WBC count of HO-1+/− mice relative to that of HO-1+/+ after 4th dose (n = 6) of 5-FU versus that of 1st dose (n = 4) (G).

We then determined whether repeated 5-FU administration also resulted in an accelerated exhaustion of the regenerative capacity and HSC reserve. HO-1+/− mice were treated with a dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) at weeks 1, 2, 5, and 18. These animals showed a smaller number of HSCs (KTLS) in their BM before the final 5-FU treatment (Figure 4F); and the initial favorable recovery of their peripheral blood leukocyte counts was lost with repeated stresses (Figure 4G). These findings support our previous data from serial BM transplantations and are indicative of an accumulative effect of HO-1 deficiency on HSC stress responses. Because defective hematopoiesis and decreases in HSC frequency have been reported as signs of early HSC exhaustion,14,15 it seems that the accelerated stress response of HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs are accompanied by an increasing decrease in HSC reserve during long-term hematopoietic stress. Thus, as hematopoietic insults are sustained and the losses in HSC reserve accumulate, the regenerative capacity of the hyperresponsive HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs decrease more rapidly and leads to inefficient hematopoietic recovery.

Disrupted activation/induction of key cell-cycle regulators under stress

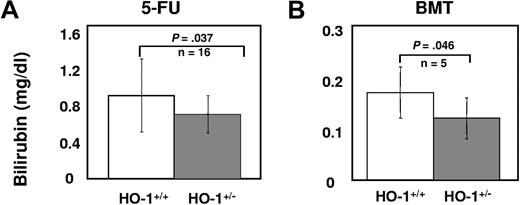

The molecular mechanism(s) underlying the role of HO-1 in the stress responses of HSCs and HPCs was examined by evaluating the activation/expression levels of key cell-cycle regulators under stress. Mice were first bled retro-orbitally to cause a blood loss of approximately 10% and were then administered heme (50 μmol/kg intraperitoneally) to mimic hemolysis (Figure 5A). After 20 hours, intracellular levels of HO-1 were lower in HO-1+/− HSCs, MPPs, and restricted progenitors than in HO-1+/+ cells (n = 4; P < .05, Figure 5B). Despite no significant differences in intracellular ROS levels (n = 4; P > .05, Figure 5C), there was less activated p38MAPK in HO-1+/− hematopoietic subsets than in wild-type mice (n = 4; P < .05, Figure 5D). This insufficient activation of p38 in HO-1+/− subsets was more apparent in MPPs than in either the more restricted progenitors or HSCs. We also observed a significant portion of HO-1+/+, but not HO-1+/−, MPPs with higher levels of p21 protein (n = 3; P = .039, Figure 5E), corroborating the finding that, under steady-state conditions, p21 mRNA levels were higher in HO-1+/+ Lin− cells compared with HO-1+/−. p38MAPK can be activated by elevated intracellular ROS14 or increased intracellular CO29,30 whereas induction of p21 expression may be either dependent29,30 or independent30 of the p38MAPK pathway. Although it is not possible to directly assess endogenous CO production, we observed lower levels of plasma bilirubin in 5-FU-treated HO-1+/− animals (n = 16; P = .037) and in the recipients of HO-1+/− BM cells (n = 6; P = .046, Figure 6), relative to the wild-type control mice. Because equimolar amounts of bilirubin and CO are produced by heme degradation, these data suggest that less CO was produced by HO-1+/− cells under these conditions.

Differential p38MAPK phosphorylation and p21 induction upon acute stress in HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs. (A) Mice were bled retro-orbitally to cause an approximately 10% blood loss, followed by heme challenge (50 μmol/kg, intraperiotoneally) to mimic a hemolysis. BM cells were prepared for immunostaining using antibodies against SLAM family members (CD150, CD48, and CD244) for measurement of levels of intracellular HO-1 protein (B) and ROS (C), phosphorylated p38MAPK (D), and p21 induction (E) within HSCs (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPPs (CD244+CD48−CD150−), and more restricted progenitors (CD48+CD244+CD150−). Values are the mean percentages indicating the gated proportion of cells. Please note that some of the histograms were skewed to the left because of the number of events on the y-axis.

Differential p38MAPK phosphorylation and p21 induction upon acute stress in HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs. (A) Mice were bled retro-orbitally to cause an approximately 10% blood loss, followed by heme challenge (50 μmol/kg, intraperiotoneally) to mimic a hemolysis. BM cells were prepared for immunostaining using antibodies against SLAM family members (CD150, CD48, and CD244) for measurement of levels of intracellular HO-1 protein (B) and ROS (C), phosphorylated p38MAPK (D), and p21 induction (E) within HSCs (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPPs (CD244+CD48−CD150−), and more restricted progenitors (CD48+CD244+CD150−). Values are the mean percentages indicating the gated proportion of cells. Please note that some of the histograms were skewed to the left because of the number of events on the y-axis.

Decreased total plasma bilirubin (milligrams per deciliter) levels in (A) 5-FU–treated HO-1+/− mice or (B) recipients of HO-1+/− BM cells. Levels of total plasma bilirubin in HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice at day 8 after receiving a single dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and in the recipients of 2 × 106 HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ BM cells at day 22 day after BM transplantation. P values were calculated using one-tailed t test.

Decreased total plasma bilirubin (milligrams per deciliter) levels in (A) 5-FU–treated HO-1+/− mice or (B) recipients of HO-1+/− BM cells. Levels of total plasma bilirubin in HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ mice at day 8 after receiving a single dose of 5-FU (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and in the recipients of 2 × 106 HO-1+/− or HO-1+/+ BM cells at day 22 day after BM transplantation. P values were calculated using one-tailed t test.

Discussion

Differential expression of HO-1 among hematopoietic subsets not only suggests a role of this protein in hematopoietic development but also provides a basis for understanding the mechanism of how HO-1 regulates the stress response of HSCs and HPCs. Under steady-state conditions, an insufficient amount of HO-1 protein resulting from the genetic HO-1 deficiency seemed to be more apparent in MPPs and more committed progenitors than in HSCs, and this was associated with p38MAPK activation and decreased levels of p21. Because overactivation of p38MAPK inhibits hematopoiesis31 and down-regulation of p21 expression promotes terminal differentiation of HPCs,32 it is likely that the combined effects of the changes in p38MAPK activation and p21 expression counteract each effects on the cell cycle and hematopoiesis in HO-1+/− mice, although the effect of the increased p21 expression in HO-1+/− HSCs remains unexplained.

Under acute stress conditions, HO-1 levels in the HO-1–deficient cells are reduced and therefore CO production may be limited, resulting in insufficient CO/p38MAPK activation, especially in MPPs in which the down-regulated CO/p38MAPK pathway occurs in conjunction with insufficient p21 induction. Insufficient p38MAPK activation enhances hematopoiesis,31 and lower levels of p21 promote differentiation of HPCs.32 Because HPCs do not have the ability to self-renew, enhanced proliferation and differentiation of these cells would lead to decreases and depletion of HPCs. This would in turn increase the demand on HSCs to replenish HPCs and further skew the self-renewal/differentiation balance toward HSC differentiation. When the reserve of HO-1+/− HSCs and HPCs is in excess, the extravagant consumption of the regenerative capacity favors hematopoietic recovery and/or reconstitution. However, when their reserve is limited or in a state of repeated stresses, premature depletion of the HSC reserve, ineffective radioprotection and serial repopulation of lethally irradiated recipients, and ultimately hematopoietic exhaustion may result. In other words, the regenerative capacity of BM cells (with ∼10-20 HSCs) seems to be exhausted before sufficient numbers of hematopoietic cells could be produced to rescue the recipients.

The differences between HO-1–deficient and wild-type HSCs and HPCs in their stress responses may be subtle and due to the regenerative capacity of HSCs, which is generally in great excess.33 Nonetheless, HO-1 regulation of the HSC stress response is significant and probably has clinical relevance in extreme conditions, such as chemo- and/or radiotherapies or BM transplantations. Understanding and controlling this pathway with currently available small molecules that that target HO-1 expression and/or activity may lead to effective modulation of HO in HSCs and HPCs. Transient and reversible inhibition might be exploited in situations in which there are ample HSCs to promote differentiation of HPCs and accelerate hematopoietic recovery or reconstitution. Conversely, in chronic states of hematopoietic insults when the stem cell reserve is limited, strategies to elevate HO-1 activity may enhance or prolong the ability of the hematopoietic system to respond to stress and potentially limit hematopoietic exhaustion.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Phyllis A. Dennery (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) for providing HO-1 knockout mouse line, Dr Derrick J. Rossi (Harvard University, Boston, MA) for comments, and Dr Stacy Burns-Guydish (Stanford University) for her critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Career Development Award to Y.A.C., a Burroughs Welcome Fund Career Award to A.J.W., and the John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Research Fund.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.-A.C. participated in designing, performing the research, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript. A.J.W. designed and performed the research, and revised the manuscript. H.K. participated in the research. H.Z. conducted the experiments. R.V. centralized the bioluminescence imaging. R.J.W. participated in designing the research, preparing, and revising the manuscript. D.K.S., I.L.W., and C.H.C. participated in designing the research, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.H.C. is a founder and consultant of Xenogen Corp., now Caliper Life Sciences. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christopher H. Contag, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatal and Developmental Medicine, E-150 Clark Center, 318 Campus Drive, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: ccontag@stanford.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal