Abstract

Somatic mutations in JAK2 are frequently found in myeloproliferative diseases, and gain-of-function JAK3 alleles have been identified in M7 acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but a role for JAK1 in AML has not been described. We screened the entire coding region of JAK1 by total exonic resequencing of bone marrow DNA samples from 94 patients with de novo AML. We identified 2 novel somatic mutations in highly conserved residues of the JAK1 gene (T478S, V623A), in 2 separate patients and confirmed these by resequencing germ line DNA samples from the same patients. Overexpression of mutant JAK1 did not transform primary murine cells in standard assays, but compared with wild-type JAK1, JAK1T478S, and JAK1V623A expression was associated with increased STAT1 activation in response to type I interferon and activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways. This is the first report to demonstrate somatic JAK1 mutations in AML and suggests that JAK1 mutations may function as disease-modifying mutations in AML pathogenesis.

Introduction

The Janus kinase (JAK) genes encode nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, including 4 family members JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2.1 Ligand binding to cytokine receptor results in trans-phosphorylation of JAK kinases, and activated JAK kinases in turn phosphorylate receptor intracellular domain tyrosines to create docking sites to recruit SH2-domain-containing downstream signaling molecules—especially the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs).2

The first genetic evidence implicating constitutive JAK-STAT activation in oncogenesis was derived from studies of signal transduction in the fruit fly. Fruit flies expressing constitutively activated Drosophila melanogaster JAK homolog, hopscotch, develop a hematopoietic neoplasia resembling leukemia.3,4 Dysregulation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway has been described in a variety of malignancies, including hematopoietic neoplasms.5 Direct evidence for aberrant JAK activation in human tumorigenesis was first confirmed by the cloning of the t(9;12) translocation breakpoint in acute lymphocytic leukemia and the identification of the TEL-JAK2 fusion protein.6 The somatic JAK2 mutation V617F has been reported in most patients with polycythemia vera (PV) as well as in approximately one third of patients with essential thrombocythemia and or idiopathic myelofibrosis.7-10 The JAK2 V617F protein demonstrates constitutively activated kinase activity in vitro and coexpression of JAK2V617F with type I cytokine receptors in Ba/F3 cells resulted in cytokine-independent JAK-STAT signaling and growth factor-independent cell growth.11 Additional JAK2 gain-of-function mutations have been identified in PV, idiopathic erythrocytosis, and acute leukemia.12,13 Furthermore, activating alleles of JAK3 have been reported in association with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia.14

JAK1 plays important roles in cytokine signal transduction15 but has not been implicated in leukemia development. We sought to evaluate the frequency and the possible contribution to leukemogenesis of JAK1 mutations in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We sequenced all exons of JAK1 using genomic DNA from the leukemic bone marrow samples of 94 patients with de novo AML, and evaluated nonsynonymous sequence changes further by sequencing matched DNA from the skin of the same patients.

Methods

Human subjects

The Washington University School of Medicine (St Louis, MO) Institutional Review Board approved an AML tissue banking study, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from all patients. A Discovery Set of 94 bone marrow DNA samples were generated from patients who fulfilled criteria including age greater than 18, at least 30% bone marrow involvement by leukemia, no more than 2 cytogenetic abnormalities, and lack of previous therapy. Punch biopsies of skin from the same patients were obtained for analysis of matched unaffected somatic cells.

Sequencing and analysis

Phi29-based whole genome amplification, primer design, PCR, and sequencing were performed as described previously.16 Sequences were confirmed by repeating PCR of the relevant amplicons from unamplified tumor and germline DNA followed by agarose gel purification and routine Big Dye sequencing. Sequence traces were assembled and scanned for variations from the reference sequence using 2 parallel mutation detection pipelines as described previously.16 Sequence coverage was evaluated with “Coverage Viewer” (R.N., manuscript in preparation) and is demonstrated for all exons in Figure S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Double-stranded coverage was obtained for 98.04% of all exonic nucleotides; single-strand coverage was obtained for 3.14%, and coverage failed for 0.83%.

Plasmid DNA constructs and retroviral production

The human JAK1 cDNA was obtained from a commercial vendor (Origene, Rockville, MD) and subcloned into the retroviral expression vector MSCV-IRES-eGFP (MIG). Both T478S and V623A mutations were introduced into the JAK1 coding sequence by site-directed mutagenesis using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by full-length DNA sequencing. Retroviral supernatants were generated and viral titers determined as described previously.17

Proliferation assays

The cell culture, cell sorting and cell proliferation assays were carried out as described previously.17

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Ba/F3 cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% fetal calf serum in the absence of recombinant murine IL-3 for 6 hours at 37°C. Cell lysates were prepared as described previously.17 Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting used polyclonal antibodies against phospho-JAK1 (Tyr1022/1023) and JAK1, phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701) and Stat1, phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) and Stat3, phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694) and Stat5, phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and Erk1/2, phospho-Akt (Ser473) and Akt, phospho-p85 PI3K binding motif and β-actin antibody. All antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) except β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO).

We used structural homology analysis (3D-PSSM [http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/3dpssm/]18 ) that recognizes structural similarity among proteins with low sequence identity based on three-dimensional position-specific scoring algorithms. Two 3-dimensional models based on threading of the submitted protein sequence onto existing structural data were created for the predicted pseudokinase and SH2 domains of JAK1. The pseudokinase model was based on an alignment of the JAK1 sequence to the structure of the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase,19 whereas the model for the SH2 domain was based on the SH2 domain of p56-LCK tyrosine kinase.

Results and discussion

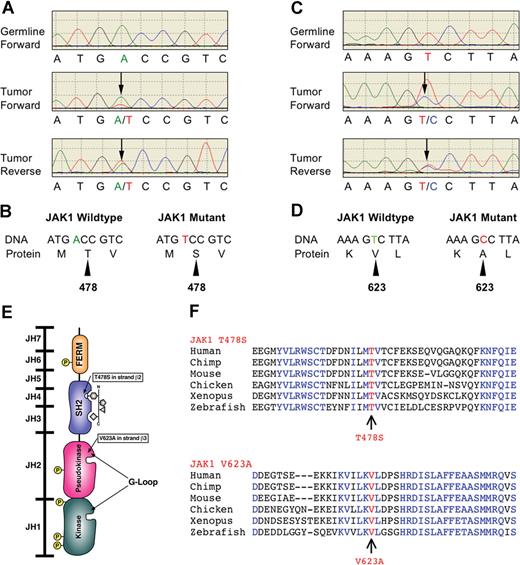

We performed complete exonic resequencing of the JAK1 gene from 94 patients with de novo AML, and discovered 2 novel heterozygous mutations in 2 patients who were not present in matched germline samples (Figure 1). These base changes predict missense mutations: threonine-to-serine substitution at residue 478 (T478S; Figure 1A,B), and valine-to-alanine substitution at residue 623 (V623A; Figure 1C,D). These sequence changes therefore created nonsynonymous changes in amino acid sequences and were somatically acquired. The JAK1T478S was found in a 63-year-old male patient with M1 morphology, trisomy 8 on routine cytogenetic analysis, and a somatic mutation in CEBPA (not shown). The JAK1V623A was found in a 37-year-old female patient with M0 morphology, normal results on cytogenetic analysis, FLT3-ITD, and a somatic mutation in RUNX1 (not shown). Despite chemotherapy, the overall survival of these patients was 1.2 and 8.5 months, respectively. We screened an independent set of 94 patients with de novo AML and did not find additional cases. Somatic JAK1 mutations were found at a frequency of approximately 1% (2/188).

Somatic nonsynonymous mutations in conserved residues of the JAK1 gene. (A,C) Electropherograms of matched tumor and germline samples from 2 patients with AML. Heterozygous mutations are indicated by double peaks ( ) consistently detected in both forward and reverse sequencing reactions but not present in the germline samples. (B,D) Change of amino acid sequences as a result of mutations. (E) Schematic diagram of JAK1 protein structure. Somatic mutations are indicated by arrows. The Thr478 residue resides in the β2 strand of the SH2 (JH3-JH4) domain near the phospho-tyrosine binding site of this domain. The Val623 residue resides in the β3 strand of the pseudo-kinase (JH2) domain in close proximity to the G-loop binding site of this domain. (F) Alignment of peptide sequences of conserved JAK1 residues. Both JAK1 mutations affect residues that are highly conserved throughout evolution.

) consistently detected in both forward and reverse sequencing reactions but not present in the germline samples. (B,D) Change of amino acid sequences as a result of mutations. (E) Schematic diagram of JAK1 protein structure. Somatic mutations are indicated by arrows. The Thr478 residue resides in the β2 strand of the SH2 (JH3-JH4) domain near the phospho-tyrosine binding site of this domain. The Val623 residue resides in the β3 strand of the pseudo-kinase (JH2) domain in close proximity to the G-loop binding site of this domain. (F) Alignment of peptide sequences of conserved JAK1 residues. Both JAK1 mutations affect residues that are highly conserved throughout evolution.

Somatic nonsynonymous mutations in conserved residues of the JAK1 gene. (A,C) Electropherograms of matched tumor and germline samples from 2 patients with AML. Heterozygous mutations are indicated by double peaks ( ) consistently detected in both forward and reverse sequencing reactions but not present in the germline samples. (B,D) Change of amino acid sequences as a result of mutations. (E) Schematic diagram of JAK1 protein structure. Somatic mutations are indicated by arrows. The Thr478 residue resides in the β2 strand of the SH2 (JH3-JH4) domain near the phospho-tyrosine binding site of this domain. The Val623 residue resides in the β3 strand of the pseudo-kinase (JH2) domain in close proximity to the G-loop binding site of this domain. (F) Alignment of peptide sequences of conserved JAK1 residues. Both JAK1 mutations affect residues that are highly conserved throughout evolution.

) consistently detected in both forward and reverse sequencing reactions but not present in the germline samples. (B,D) Change of amino acid sequences as a result of mutations. (E) Schematic diagram of JAK1 protein structure. Somatic mutations are indicated by arrows. The Thr478 residue resides in the β2 strand of the SH2 (JH3-JH4) domain near the phospho-tyrosine binding site of this domain. The Val623 residue resides in the β3 strand of the pseudo-kinase (JH2) domain in close proximity to the G-loop binding site of this domain. (F) Alignment of peptide sequences of conserved JAK1 residues. Both JAK1 mutations affect residues that are highly conserved throughout evolution.

To analyze the context of the JAK1 mutations within the encoded JAK1 protein, we used a bioinformatics approach to construct models of JAK1 domain structures. Inspection of these models revealed that the T478S mutation found in JAK1 is predicted to be in the β2 strand of the JAK1 SH2 domain and within 5 Å of residues creating the phosphotyrosine binding pocket used by SH2 domains for ligand binding (Figure 1E). Similar analysis of the pseudokinase model revealed that the V623A mutation is predicted to be in the β3 strand of the N-terminal lobe of this domain within 5 Å of the so-called G-loop, which in active tyrosine kinases participates in coordination of ATP for the productive γ-phosphate transfer to a substrate coordinated by the C-terminal kinase lobe (Figure 1E).

Analysis of sequence alignment of JAK1 genes from different species revealed the Thr478 and Val623 residues to be highly conserved throughout vertebrate evolution (Figure 1F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the somatic mutations we discovered occurred in residues likely to play important roles in the structure and function of the JAK1 protein.

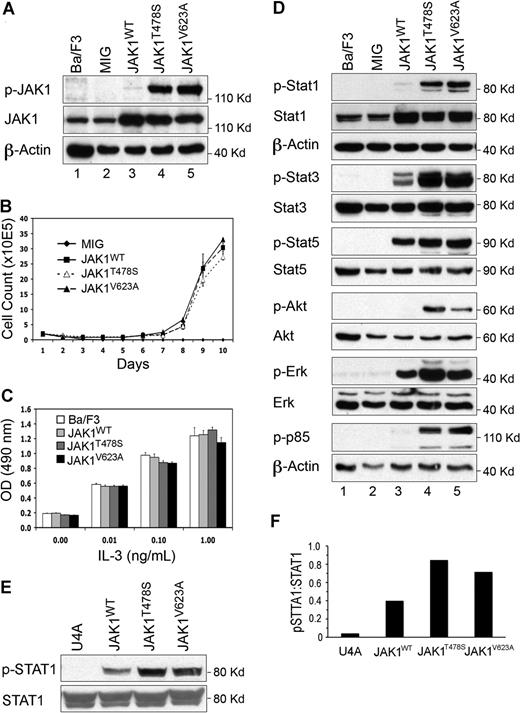

To assess the potential biologic function of the discovered JAK1 mutations, JAK1T478S, JAK1V623A, or wild-type JAK1 (JAK1WT) were expressed in IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells (Figure 2A), and cell growth was measured after the withdrawal of IL-3. Ba/F3 cells expressing JAK1T478S or JAK1V623A mutants were able to grow in the absence of IL-3, in contrast to parental and vector control cells (Figure 2B). Overexpression of JAK1WT conferred factor independent growth with similar kinetics. Together, these data suggest that JAK1 is an oncogene with the ability to provide a proliferative advantage to hematopoietic cells. However, the JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A mutations provided no additional growth advantage in this assay. Staerk et al20 found that overexpression of JAK1WT fails to rapidly induce factor-independent growth in Ba/F3 cells (assayed 4 days after selection). Our data that JAK1WT-overexpressing cells require more than 7 days to grow out in the absence of IL-3 are consistent with these published data.

Somatic JAK1 mutations facilitate the activation of downstream signaling pathways. (A) Autophosphorylation of mutant JAK1 proteins. Mutant, but not wild-type, JAK1 proteins are activated. (B) Growth of Ba/F3 cells expressing JAK1 and mutants in the absence of IL-3. Both mutant and wild-type JAK1-expressing cells can grow in the absence of IL-3. (C) Mutant JAK1 proteins do not affect sensitivity of Ba/F3 cells to IL-3. Cells expressing wild-type or JAK1 mutants were plated in different concentrations of IL-3, and cell growth was measured by MTT assay. The V623A mutant was mildly resistant to high doses of IL-3. Error bars represent SD. (D) Activation of downstream signaling pathways by JAK1 mutants. Protein lysates of Ba/F3 cells expressing wild type and JAK1 mutants were analyzed by Western blot using phospho-specific antibodies shown. Stat1, Stat3, Akt, and Erk signaling was activated in cells expressing each JAK1 mutation. (E) Activation of STAT1 by interferon α in cells expressing JAK1WT, JAK1T478S, and JAK1V623A. STAT1 phosphorylation 15 minutes after stimulation was consistently increased in cells expressing JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A compared with JAK1WT. (F) Densitometry of results in panel E showing increased STAT1 phosphorylation in JAK1 mutant-expressing cells. U4A parental cells that do not express JAK1 are shown as controls. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments, and a representative example is shown.

Somatic JAK1 mutations facilitate the activation of downstream signaling pathways. (A) Autophosphorylation of mutant JAK1 proteins. Mutant, but not wild-type, JAK1 proteins are activated. (B) Growth of Ba/F3 cells expressing JAK1 and mutants in the absence of IL-3. Both mutant and wild-type JAK1-expressing cells can grow in the absence of IL-3. (C) Mutant JAK1 proteins do not affect sensitivity of Ba/F3 cells to IL-3. Cells expressing wild-type or JAK1 mutants were plated in different concentrations of IL-3, and cell growth was measured by MTT assay. The V623A mutant was mildly resistant to high doses of IL-3. Error bars represent SD. (D) Activation of downstream signaling pathways by JAK1 mutants. Protein lysates of Ba/F3 cells expressing wild type and JAK1 mutants were analyzed by Western blot using phospho-specific antibodies shown. Stat1, Stat3, Akt, and Erk signaling was activated in cells expressing each JAK1 mutation. (E) Activation of STAT1 by interferon α in cells expressing JAK1WT, JAK1T478S, and JAK1V623A. STAT1 phosphorylation 15 minutes after stimulation was consistently increased in cells expressing JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A compared with JAK1WT. (F) Densitometry of results in panel E showing increased STAT1 phosphorylation in JAK1 mutant-expressing cells. U4A parental cells that do not express JAK1 are shown as controls. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments, and a representative example is shown.

The JAK2V617F mutation increases the proliferation of Ba/F3 cells coexpressing erythropoietin receptor (EPO-R) in response to limiting dilutions of cytokine,11 so we assessed whether the JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A mutations similarly sensitized cells to growth factors. Ba/F3 cells expressing the JAK1T478S or JAK1V623A mutations were grown in limiting dilutions of IL-3, but expression of the discovered JAK1 mutations did not affect the growth of Ba/F3 cells in response to IL-3 as measured by MTT assay (Figure 2C). Ba/F3 cells coexpressing EPO-R, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR), or thrombopoietin receptor (TPO-R) with JAK1 mutants plated in limiting dilutions of the respective cytokines responded with similar growth kinetics, demonstrating no synergistic effect on these receptors (data not shown). Finally, we assessed the activation of downstream signaling pathways in Ba/F3 cells expressing JAK1T478S or JAK1V623A. When cells for analysis were harvested after growth in the absence of IL-3, the specific activation of multiple downstream pathways was observed, including Stat3, Stat5, Akt, and mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk; Figure 2D). However, JAK1 autophosphorylation and downstream signaling were not observed in cells expressing JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A before selection in the absence of IL-3 (not shown). These results are consistent with the observations of Staerk et al,20 made using an engineered JAK1 mutant (V658F) and suggest that these mutations can only activate down-stream signaling pathways by cooperating with additional events or cytokine stimulation. Expression of JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A in primary murine hematopoietic progenitor cells also failed to induce disease in transplanted mice or increased colonies in methylcellulose, demonstrating that these mutations are not by themselves strongly transforming (not shown).

Because JAK1 is known to mediate signal transduction by the type I interferon receptor,21 we examined the responses to interferon α of cells expressing JAK1WT, JAK1T478S, and JAK1V623A. We found that, compared with JAK1WT-expressing cells, cells expressing JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A consistently phosphorylated STAT1 to a greater degree after interferon stimulation (Figure 2E,F). Together, these data demonstrate that JAK1T478S and JAK1V623A are functionally altered proteins that do not directly induce transformation, but rather modify the activation of downstream signaling pathways in response to additional signals.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Robert Schreiber for valuable reagents and discussion and Joseph M. Garrett, Kimberley E. Baynit, and Gautham Vaidyanathan for data analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA101937.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Z.X. and M.H.T. designed and performed research, and wrote the manuscript. Y.Z. and W.S. analyzed data. V.M., D.H.F., Y.K., A.M., R.E.R., T.M., M.D.M., J.E.P., M.W., S.H., R.N., E.R.M., and R.K.W. performed research. J.F.D., D.C.L., T.A.G., and T.J.L. designed research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael H. Tomasson, MD, Division of Oncology, Department of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8007, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: tomasson@wustl.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal