In this study, we explored the telomeric changes that occur in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), in which telomere length has recently been demonstrated to be a powerful prognostic marker. We carried out a transcriptomic analysis of telomerase components (hTERT and DYSKERIN), shelterin proteins (TRF1, TRF2, hRAP1, TIN2, POT1, and TPP1), and a set of multifunctional proteins involved in telomere maintenance (hEST1A, MRE11, RAD50, Ku80, and RPA1) in peripheral B cells from 42 B-CLL patients and 20 healthy donors. We found that, in B-CLL cells, the expressions of hTERT, DYSKERIN, TRF1, hRAP1, POT1, hEST1A, MRE11, RAD50, and KU80 were more than 2-fold reduced (P < .001), contrasting with the higher expression of TPP1 and RPA1 (P < .001). This differential expression pattern suggests that both telomerase down-regulation and changes in telomeric proteins composition are involved in the pathogenesis of B-CLL.

Introduction

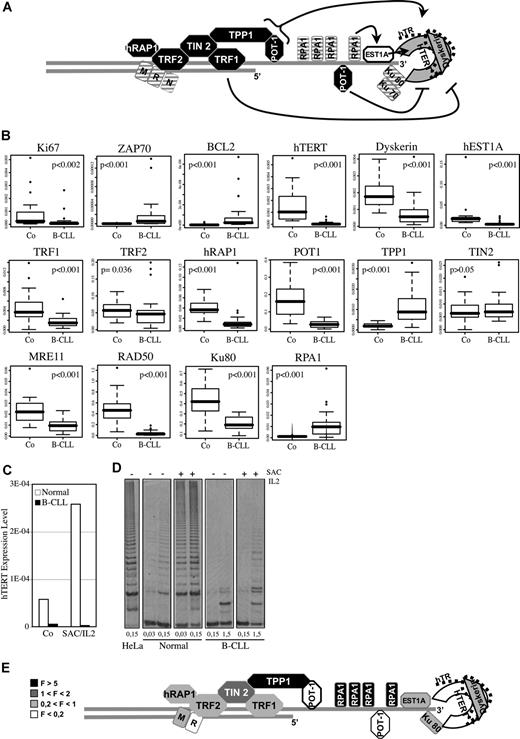

Telomeres are nucleoprotein structures that cap chromosomes and shorten with each division. Telomere structure and functions depend on the telomerase enzyme (hTERT, hTR, DYSKERIN) for elongation,1 on the shelterin complex (TRF1, TRF2, TIN2, hRAP1, TPP1, POT1) that regulates telomere length and protects them against degradation and fusion, and on a set of multifunctional factors, including RPA1, hEST1A, KU70/KU80 and the RAD50-MRE11-NBS1 complex2 (Figure 1A).

The telomere maintenance system in B-CLL. (A) Telomeric structure maintenance involved numerous proteins, whose precise function still remains largely unknown. We summarize here the actual data in the field. The telomeric double-strand DNA protrudes to form a single-strand overhang. The telomerase complex, in gray, is formed by the catalytic subunit hTERT associated with the template RNA named hTR, and Dyskerin. POT1-TTP1 heterodimer binds to the telomeric overhang and activates the processivity of telomerase.23 hEST1A24 and Ku70/80 interact with the telomerase, whereas RPA1 binds single-strand DNA. Based on studies in yeast, these 3 components are thought to facilitate the access of telomerase to chromosome ends.2 The shelterin complex, in black, is required to protect telomeres.2 TRF1 inhibits telomerase, whereas POT1 behaves either as an activator or an inhibitor of telomerase activity, depending on its mode of fixation to chromosome ends. These complexes interact with DNA-damage response proteins, as KU70/KU80 and the MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1). Among these cofactors, those whose down-regulation is associated with telomere shortening, are depicted as crossed-hatched.2 (B) Quantitative PCR analyses were led on cDNA of peripheral B cells from 42 B-CLL patients and 20 healthy donors. All the box-plots correspond to the β-ACTIN normalized data, except for POT1 (RPL13A) and BCL-2 (RPL19) for which no statistical test can be applied on β-actin-derived data. The corresponding P values are shown in each box. The horizontal lines are medians, the boxes 25th percentiles, and the whiskers 75th percentiles. (C,D) Analyses were carried out on cells from a B-CLL patient and a normal healthy donor, before (Co) and after 48 hours of SAC/IL2 (SAC/IL2) treatment. (C) Q-PCR analysis of hTERT expression is shown (reference gene: β-ACTIN). (D) A trap assay was realized to measure telomerase activity, the gel analysis is shown (different lanes of the same gel are shown) for the different conditions tested and for a positive control (HeLa cells), and quantities of protein per assay are mentioned (mg). (E) Fold expression variation of telomeric proteins observed in B-CLL versus normal B cells. F indicates multiplication factor.

The telomere maintenance system in B-CLL. (A) Telomeric structure maintenance involved numerous proteins, whose precise function still remains largely unknown. We summarize here the actual data in the field. The telomeric double-strand DNA protrudes to form a single-strand overhang. The telomerase complex, in gray, is formed by the catalytic subunit hTERT associated with the template RNA named hTR, and Dyskerin. POT1-TTP1 heterodimer binds to the telomeric overhang and activates the processivity of telomerase.23 hEST1A24 and Ku70/80 interact with the telomerase, whereas RPA1 binds single-strand DNA. Based on studies in yeast, these 3 components are thought to facilitate the access of telomerase to chromosome ends.2 The shelterin complex, in black, is required to protect telomeres.2 TRF1 inhibits telomerase, whereas POT1 behaves either as an activator or an inhibitor of telomerase activity, depending on its mode of fixation to chromosome ends. These complexes interact with DNA-damage response proteins, as KU70/KU80 and the MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1). Among these cofactors, those whose down-regulation is associated with telomere shortening, are depicted as crossed-hatched.2 (B) Quantitative PCR analyses were led on cDNA of peripheral B cells from 42 B-CLL patients and 20 healthy donors. All the box-plots correspond to the β-ACTIN normalized data, except for POT1 (RPL13A) and BCL-2 (RPL19) for which no statistical test can be applied on β-actin-derived data. The corresponding P values are shown in each box. The horizontal lines are medians, the boxes 25th percentiles, and the whiskers 75th percentiles. (C,D) Analyses were carried out on cells from a B-CLL patient and a normal healthy donor, before (Co) and after 48 hours of SAC/IL2 (SAC/IL2) treatment. (C) Q-PCR analysis of hTERT expression is shown (reference gene: β-ACTIN). (D) A trap assay was realized to measure telomerase activity, the gel analysis is shown (different lanes of the same gel are shown) for the different conditions tested and for a positive control (HeLa cells), and quantities of protein per assay are mentioned (mg). (E) Fold expression variation of telomeric proteins observed in B-CLL versus normal B cells. F indicates multiplication factor.

Telomerase activity is absent or very low in somatic cells and increased in proliferative lymphoid cells.3 In most cancer cells, the catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) is overexpressed to allow their long-term proliferation.4 Research in oncogenesis is now focusing on the other telomeric genes, especially the shelterin complex.5,,,,–10 Specific changes in the expression of these genes in cancers may provide new knowledge about oncogenesis and useful clinical markers, but would also lead to the development of new therapeutic agents.

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) results from the progressive accumulation of a leukemic clone (for review, see Chiorazzi and Ferrarini11 ) that shows lower telomerase activity at disease onset12 and increased activity in advanced stages and bad prognosis group.13 Telomeres are shorter in B-CLL cells versus normal B cells, and especially short for patients with bad prognosis. Telomere length is thus a powerful prognostic marker for B-CLL.13,14 In this work, we investigated whether the transcriptional status of the telomeric proteins is modified in B cells from B-CLL patients.

Methods

Isolation of human B cells

After consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and according to institutional guidelines, total blood samples were collected from 20 healthy donors (at the “Etablissement Français du Sang” of Lyon and Pitié-Salpétrière Hospital) and from 42 B-CLL patients (at the Lyon Sud and Pitié-Salpétrière Hospitals). Diagnoses were confirmed using morphology and flow-cytometry usual B-CLL characteristics (Matutes score ≥ 4). B lymphocytes were purified from peripheral blood by negative selection using the RosetteSep Human B-cell enrichment cocktail (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). The percentage of CD19+ cells was determined by cytometric assay using an α-CD19-PE antibody (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). More than 75% and 90% of CD19+ labeling was obtained for normal B cells and B-CLL cells, respectively. Binet stage, karyotype, fluorescent in situ hybridization, and mutational status (analyses were carried out as previously described15 ) features are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical features of B-CLL patients

| . | Binet stage . | Mutational status . | Del 13q14 . | del 11q22 . | +12 . | del 17p13 . | Karyotype analysis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC′1 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′3 | A | M | — | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′7 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC′9 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′11 | A | M | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′26 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′19 | A+ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′23 | A+ | M | + | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′28 | A | M | + | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′31 | A+ | UM | — | — | + | — | +12, t(14;19) |

| LLC′32 | A | M | — | — | + | — | ND |

| LLC′13 | B | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′14 | A+ | M | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′17 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′29 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′15 | B | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC2 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC3 | NA | M | + | — | — | — | del 13(q13q14) |

| LLC5 | NA | M | + | — | — | — | del 13(q22q31) |

| LLC6 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC7 | A | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC9 | A+ | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC 11 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | add 14q32/del 13q(q12-q22) |

| LLC18 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC21 | A/B | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC23 | B+ | M | + | — | — | — | 13q21abnormality |

| LLC30 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC31 | A+ | M | + | — | — | + | t(11;14)/del17p11 |

| LLC33 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC34 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC39 | C | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC41 | A | M | + | — | — | — | t(14;18)(q32;q21) |

| LLC44 | A | M | + | — | — | — | del13q |

| LLC47 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC50 | C | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC51 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC54 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC55 | A | M | + | — | — | — | del6q |

| LLC56 | B | UM | — | — | + | — | +12 |

| LLC57 | NA | M | — | — | — | — | t(7;22) |

| LLC95 | NA | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC98 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| . | Binet stage . | Mutational status . | Del 13q14 . | del 11q22 . | +12 . | del 17p13 . | Karyotype analysis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC′1 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′3 | A | M | — | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′7 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC′9 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′11 | A | M | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′26 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′19 | A+ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′23 | A+ | M | + | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′28 | A | M | + | — | — | + | ND |

| LLC′31 | A+ | UM | — | — | + | — | +12, t(14;19) |

| LLC′32 | A | M | — | — | + | — | ND |

| LLC′13 | B | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′14 | A+ | M | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC′17 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′29 | A | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC′15 | B | UM | + | — | — | — | ND |

| LLC2 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC3 | NA | M | + | — | — | — | del 13(q13q14) |

| LLC5 | NA | M | + | — | — | — | del 13(q22q31) |

| LLC6 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC7 | A | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC9 | A+ | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC 11 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | add 14q32/del 13q(q12-q22) |

| LLC18 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC21 | A/B | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC23 | B+ | M | + | — | — | — | 13q21abnormality |

| LLC30 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC31 | A+ | M | + | — | — | + | t(11;14)/del17p11 |

| LLC33 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC34 | A | UM | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC39 | C | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC41 | A | M | + | — | — | — | t(14;18)(q32;q21) |

| LLC44 | A | M | + | — | — | — | del13q |

| LLC47 | A | M | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| LLC50 | C | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC51 | A | M | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC54 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

| LLC55 | A | M | + | — | — | — | del6q |

| LLC56 | B | UM | — | — | + | — | +12 |

| LLC57 | NA | M | — | — | — | — | t(7;22) |

| LLC95 | NA | UM | — | — | — | — | N |

| LLC98 | A | M | + | — | — | — | N |

FISH analyses were led to determine 13q14, 17p13, 11q22 deletion and trisomy 12 (+12).

ND indicates not done; NA, not available; N, normal; +, previously treated; M, mutated; UM, unmutated; add, addition; del, deletion; t, translocation; and —, not applicable.

BCR stimulation, cell-cycle assay, and telomerase activity

B cells cultured on 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented RPMI, under 5% CO2 atmosphere, were treated 48 hours by 0.001% of SAC suspension (Staphylococcus aureus Cowan strain I; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and 1 ng/mL of interkeukin-2 (Boehringer, Reims, France). Telomerase activity was measured by TRAPeze assay following the kit instruction (Intergent, New York, NY).

Reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA extracted from purified B cells (Nalgene, New York, NY) was reverse-transcribed using random hexamer, Superscript II, and dNTP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR (Epicentre, Invitrogen, QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) on opticon 3 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was runfollowing the producer instructions. Sequences of primers used for PCR are listed in Table 2.

Sequences of primer used in the qPCR assays

| Gene . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . |

|---|---|---|

| hTERT | TGTTTCTGGATTTGCAGGTG | GTTCTTGGCTTTCAGGATGG |

| DYSKERIN | CTGCTATGGGGCCAAGATTA | CCATGGTCGCAGGTAGAGAT |

| hEST1A | AGGAACTGCTGGACAAGAGGA | CGCAACATTTCCCCTACACT |

| TRF1 | GCTGTTTGTATGGAAAATGGC | CCGCTGCCTTCATTAGAAAG |

| TRF2 | GACCTTCCAGCAGAAGATGCT | GTTGGAGGATTCCGTAGCTG |

| hRAP1 | CGGGGAACCACAGAATAAGA | CTCAGGTGTGGGTGGATCAT |

| POT1 | TGGGTATTGTACCCCTCCAA | GATGAAGCATTCCAACCACGG |

| TPP1 | CCCGCAGAGTTCTATCTCCA | GGACAGTGATAGGCCTGCAT |

| TIN2 | GGAGTTTCTGCGATCTCTGC | GATCCCGCACTATAGGTCCA |

| MRE11 | GCCTTCCCGAAATGTCACTA | TTCAAAATCAACCCCTTTCG |

| RAD50 | CTTGGATATGCGAGGACGAT | CCAGAAGCTGGAAGTTACGC |

| KU80 | CCCCAATTCAGCAGCATATT | CCTTCAGCCAGACTGGAGAC |

| RPA1 | AGGCACCCTGAAGATTGCTA | GGCGTCTTCATAGCTCTTGC |

| Ki-67 | ATGCAGACCCAGTGGACACC | TGCTGCCGGTTAAGTTCTCT |

| ZAP-70 | CAGCTGGACAACCCCTACAT | GGTTAACCAGCAGGACGTTG |

| BCL2 | GGTGGAGGAGCTCTTCAGG | GCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTC |

| β-ACTIN | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG | TCCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGA |

| RPL13A | AGCTCATGAGGCTACGGAAA | CTTGCTCCCAGCTTCCTATG |

| RPL19 | ATCGATCGCCACATGTATCA | GCGTGCTTCCTTGGTCTTAG |

| Gene . | Forward primer . | Reverse primer . |

|---|---|---|

| hTERT | TGTTTCTGGATTTGCAGGTG | GTTCTTGGCTTTCAGGATGG |

| DYSKERIN | CTGCTATGGGGCCAAGATTA | CCATGGTCGCAGGTAGAGAT |

| hEST1A | AGGAACTGCTGGACAAGAGGA | CGCAACATTTCCCCTACACT |

| TRF1 | GCTGTTTGTATGGAAAATGGC | CCGCTGCCTTCATTAGAAAG |

| TRF2 | GACCTTCCAGCAGAAGATGCT | GTTGGAGGATTCCGTAGCTG |

| hRAP1 | CGGGGAACCACAGAATAAGA | CTCAGGTGTGGGTGGATCAT |

| POT1 | TGGGTATTGTACCCCTCCAA | GATGAAGCATTCCAACCACGG |

| TPP1 | CCCGCAGAGTTCTATCTCCA | GGACAGTGATAGGCCTGCAT |

| TIN2 | GGAGTTTCTGCGATCTCTGC | GATCCCGCACTATAGGTCCA |

| MRE11 | GCCTTCCCGAAATGTCACTA | TTCAAAATCAACCCCTTTCG |

| RAD50 | CTTGGATATGCGAGGACGAT | CCAGAAGCTGGAAGTTACGC |

| KU80 | CCCCAATTCAGCAGCATATT | CCTTCAGCCAGACTGGAGAC |

| RPA1 | AGGCACCCTGAAGATTGCTA | GGCGTCTTCATAGCTCTTGC |

| Ki-67 | ATGCAGACCCAGTGGACACC | TGCTGCCGGTTAAGTTCTCT |

| ZAP-70 | CAGCTGGACAACCCCTACAT | GGTTAACCAGCAGGACGTTG |

| BCL2 | GGTGGAGGAGCTCTTCAGG | GCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTC |

| β-ACTIN | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG | TCCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGA |

| RPL13A | AGCTCATGAGGCTACGGAAA | CTTGCTCCCAGCTTCCTATG |

| RPL19 | ATCGATCGCCACATGTATCA | GCGTGCTTCCTTGGTCTTAG |

Statistical analysis

Gene expression levels were normalized using 3 reference genes (RPL13A, β-ACTIN, and RPL19). Distribution and variance equality were analyzed for each gene, in normal and B-CLL populations. Three different tests were run: Student (for gaussian populations with equal variance), Welch (for gaussian populations with different variance), or Wilcoxon (for nongaussian populations with equal variance) to determine the P value.

Results and Discussion

We determined the mRNA level of telomeric proteins in B cells from 42 B-CLL patients and 20 healthy donors. As previously published, ZAP-70 and BCL2 expressions were increased and those of KI-67 and hTERT were decreased (respective ratios: 25.6, 21, 0.26, and 0.04)12,16,–18 (Figure 1B,E). We further showed that levels of hTERT and telomerase activity are correlated in B cells from one patient and one healthy donor (Figure 1C,D). Both levels cannot be increased by mitogenic stimulation in the patient cells, in which no cycling activity was observed (data not shown). Among the other factors implicated in telomerase activity, the expression of DYSKERIN, POT1, and hEST1A is also significantly reduced (2.4-, 5.8-, and 4.8-fold, respectively), whereas the one of TPP1 is increased (5.1-fold). Concerning the other shelterin components, the mRNA levels are lower in B-CLL cells for TRF1 and hRAP1 (2.9- and 3.0-fold, respectively), slightly reduced for TRF2 (1.2-fold), and almost unchanged for TIN2. We also observed a decrease in mRNA level of KU80, MRE11, and RAD50 (2.1-, 2.4-, and 11.1-fold, respectively) (Figure 1B,E) and an increase in RPA1 (9.7-fold).

Although these changes have to be confirmed at the protein level, they are expected to greatly affect the function of telomeres in B-CLL cells. The lower expression level of various factors involved in telomerase activity should impair telomere regeneration at each S-phase. Moreover, the altered expression of telomere capping factors might disrupt the capping complex, facilitating telomere degradation and shortening independently of the telomerase status. This correlates with telomeric damages already observed in B-CLL cells.11,19 Our results, together with the fact that these cells could proliferate at appreciable levels,20 suggest that the short telomeres observed in B-CLL cells in comparison with normal B cells but also with other types of B-cell malignancies21 might result from specific defects in telomerase-dependent and telomerase-independent pathways of telomere elongation. This would also explain the shorter telomeres observed in patients with severe outcome, despite an increase in telomerase activity.13 Finally, our results suggest that B-CLL cells may be particularly sensitive to telomere-damaging drugs, such as BIBR32, which exerts a cytotoxic effect on B-CLL cells mainly by damaging telomeres.22

In conclusion, our results provide the first evidence of a global modification in the expression of telomeric genes in B-CLL, which is characterized by a low expression of many components involved in telomere elongation and capping.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D.P.'s medical supervisor Pr Jean André and Corrine Béal for sampling.

La Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer supported E.G.'s laboratory (équipe labellisée); Institut Nationale du Cancer (program EPIPRO) supported E.G.'s and G.S.'s laboratories; and Association Recherche contre le Cancer (ARECA program on Epigenetic Profiling) financed C.T.R.'s fellowship and the laboratories of L.S. and J.D.

Authorship

Contribution: D.P. performed research, interpreted data, and cowrote the article; C.T.R., A.B., A.R.C., and E.B.S. performed research; H.M.-B., E.C.-B., G.S., L.S., and J.D. collected biologic samples and reviewed the article; E.G. designed and coordinated the research, interpreted data, and cowrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eric Gilson, UMR5239, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Sud, 165 Chemin du Grand Revoyet, 69495 Pierre Bénite, France; e-mail: eric.gilson@ens-lyon.fr.