MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a newly discovered class of posttranscriptional regulatory noncoding small RNAs. Recent evidence has shown that miRNA misexpression correlates with progression of various human cancers. Friend erythroleukemia has been used as an excellent system for the identification and characterization of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes involved in neoplastic transformation. Using this model, we have isolated a novel integration site designated Fli-3, from a Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV)–induced erythroleukemia. The Fli-3 transcription unit is a murine homologue of the human gene C13orf25 that includes a region encoding the mir-17–92 miRNA cluster. C13orf25 is the target gene of 13q31 chromosomal amplification in human B-cell lymphomas and other malignancies. The erythroleukemias that have acquired either insertional activation or amplification of Fli-3 express higher levels of the primary or mature miRNAs derived from mir-17–92. The ectopic expression of Fli-3 in an erythroblastic cell line switches erythropoietin (Epo)–induced differentiation to Epo-induced proliferation through activation of the Ras and PI3K pathways. Such a response is associated with alteration in the expression of several regulatory factors, such as Spi-1 and p27 (Kip1). These findings highlight the potential of the Fli-3 encoding mir-17–92 in the development of erythroleukemia and its important role in hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Studies of genes associated with retrovirus-induced neoplasia form the basis of much of our present knowledge of oncogenes, and have contributed to our understanding of both gene function and the neoplastic process.1 Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV) does not contain any oncogenic sequences. Instead it induces tumors by activating or inactivating oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, respectively, through a process known as retroviral insertional mutagenesis.2 Previous studies in our laboratory and others have demonstrated that the pivotal genetic event associated with erythroleukemia initiation is the insertional activation of the Ets-related gene Fli-1.3,–5 Progression toward more malignant stages has been shown to be associated with insertional inactivation of either p53 or p45 NFE2.6,,,–10

To further investigate the role of p53 in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia, p53-deficient mice were infected with F-MuLV. While the loss of p53 in primary erythroleukemias accelerated tumor initiation and immortalization,11 10% of these tumors did not acquire an insertional activation of the Fli-1 locus, and the cell lines established from these erythroleukemias did not express endogenous Fli-1. The transformation of these cells is attributable to insertional activation or inactivation of another gene, since F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia usually requires Fli-1 activation for erythroid transformation.3 Therefore, the investigation of a novel site of proviral integration is necessary to uncover the mechanism of transformation in the Fli-1–negative erythroleukemias. This study describes the identification of a novel integration site, designated Friend murine leukemia integration site 3 (Fli-3), containing sequences identical to the miRNA gene family.

miRNAs are small, non–protein-encoding RNAs that play important roles in a variety of biologic processes. They act by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA of their target gene. This binding process reduces the stability of these mRNAs, thereby altering the protein expression.12,13 Some miRNA genes exist in clusters that can be expressed as single transcriptional polycistron.14 Emerging evidence suggests the potential involvement of altered regulation of miRNA in the pathogenesis of human cancers.15,,,,–20

Fli-3 is a murine homologue of the human C13orf25 gene, a newly identified target gene for 13q31-q32 chromosomal amplification in B-cell–type lymphomas.21 C13orf25 contains sequences corresponding to the mir-17–92 polycistron. He et al22 have recently reported that mir-17–92 is highly expressed in B-cell lymphomas and its expression in c-myc–overexpressing transgenic mice accelerated tumorigenicity by an as-yet-undefined process. Hayashita et al18 also showed that mir-17–92 is overexpressed in human lung cancer and enhances cell proliferation. Interestingly, the Fli-3 transcript contains the identical mir-17–92 sequence, suggesting that this murine homologue may play a similar role in the development and progression of F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia. A recent study has reported proviral integrations within or nearby the mir-17–92 miRNA in T lymphomas induced by SL3–3 murine leukemia virus that indicates the importance of this cluster in various cancers.23

Although misexpression of the mir-17–92 cluster has been reported in several tumors, the mechanism by which this cluster exerts its tumorigenic activity remains to be determined. In this study, we show that the mir-17–92 cluster is the candidate gene of a newly discovered proviral integration site, Fli-3, that is markedly overexpressed in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia as a result of either retroviral insertional activation or gene amplification. Furthermore, introduction of mir-17–92 enhances erythroblast transformation and proliferation through changes in the erythropoietin (Epo)–Epo receptor (EpoR) signal transduction pathway. This shows the importance of mir-17–92 in erythroblast transformation and hematopoiesis. The study presented here provides an experimental model to elucidate the mechanism by which this miRNA cluster alters cellular pathways leading to erythroleukemia development.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The establishment of the erythroleukemia cell lines KH9, KH11, KH14, and KH16 has been previously described.11 These cells were maintained in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) without or with Epo (Janssen-Ortho, Toronto, ON) and stem cell factor (SCF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). HB60–5 cells were maintained in the same medium supplemented with 0.2 U Epo and 100 mg SCF per milliliter. To induce differentiation, HB60–5 cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in the presence of 10% FBS and 1 U Epo per milliliter. NIH-3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma, Oakville, ON).

DNA probes

The F-MuLV envelope probe is an 830-bp BamHI fragment derived from plasmid pHC6.3 The hemoglobin alpha (α-globin) probe is a 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment from plasmid PB1. The 750-bp PstI/XbaI fragment of mouse GAPDH cDNA was used to check the amount of RNA loaded. All DNA probes were labeled as described elsewhere.24

DNA isolation and Southern blotting

High-molecular-weight DNA isolated as described was digested with restriction enzymes, electrophoresed on 0.8% agarose gels, and hybridized with 2 × 106 cpm/mL of randomly primed probe as previously described.6 Scanned images were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

RNA extraction and Northern blotting

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells by using the TRIZOL reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). RNA (20 μg) was dissolved in 2.2 M formaldehyde, denatured at 65°C for 15 minutes, separated in 1% agarose gel containing 0.66 M formaldehyde, and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The filters were hybridized with radioactively labeled probe (2 × 106 cpm/mL α-32P-dCTP).

Isolation of cDNA clones and nucleotide sequence determination

To isolate the virus integration site, 1 × 106 phage particles from KH9 or KH16 genomic libraries was screened with the F-MuLV envelope probe. After 3-cycle screening, DNA fragments were isolated from plaque-purified phage and subcloned into pGEM-7Zf (+) at the EcoRI site. One of the fragments, designated Fli-3 probe, gave rearrangement at KH9 cells and showed DNA amplification in KH16 cells by Southern blot analysis.

To isolate the transcripts, cDNA libraries constructed from mRNA of the KH9 cell line were screened with the Fli-3 probe. The inserts from positive clones were isolated and subcloned into the pGEM-7 vector. The isolated cDNA was then sequenced and compared with other genes in GenBank (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Slot blots of amplified cDNAs from hematopoietic precursors

Determination of the structure of the Fli-3 gene

The Fli-3 probe was used to screen a Mus musculus bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) that resulted in isolation of a BAC clone spanning the entire region. The genomic fragments were digested with various endonucleases and cloned into pT7 Blue vectors (Invitrogen). The exon-intron boundaries were determined by comparing the genomic DNA sequence with the cDNA sequence. The open reading frame (ORF) of the cDNA was determined using the ATGpr program (Helix Research Institute, Chiba, Japan).

Construction of retroviral expression vectors

To generate the MSCV-Fli-3-mir-92 retrovirus, the 2.2-kb insert isolated from screening cDNA libraries using the Fli-3 probe was cloned into the EcoRI site of the MSCV2.1 expression vector (Invitrogen). The 4.4-kb Fli-3-mir-17–92 retrovirus was constructed by cloning the 4.4-kb BglII/PmlI fragment of Fli-3, isolated from Mus musculus BAC clone, into the BglII and HpaI sites of the MSCV2.1 vector. The 4.4-kb Fli-3-mir-17–92 genomic DNA contains the entire 3′-Fli-3 sequence, mir-17–92, and upstream sequences (Figure 3A). The MigR1-Fli-1 vector was constructed by cloning a 1.7-kb Fli-1 cDNA fragment into the EcoRI site of the MigR1 vector.

Transfection and infection

GP+A packaging cells were maintained in α-MEM containing 10% FBS. Transfections were performed in 60-mm-diameter plates with 4 μg of the DNA construct using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 48 hours of transfection, the cells were selected in medium containing G418 (0.8 mg/mL; Gibco) for 2 weeks. For infection, 5 × 106 HB60–5 or 106 NIH-3T3 cells were mixed with supernatant collected from GP+A cells transfected with MigR1-Fli-1, Fli-3-mir-92, or Fli-3-mir-17–92 expression vectors, or the empty vector. After 24 hours of infection, the cells were selected for neomycin resistance in growth medium containing 0.8 mg/mL G418 for about 2 weeks. HB60–5 cells infected with the retrovirus containing Fli-3-mir-92 or Fli-3-mir-17–92 were designated as HB60–5-Fli-3-mir-92 or HB60–5-Fli-3-mir-17–92. A similar strategy was used to express Fli-3 in NIH-3T3 cells.

Reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

The total RNA was extracted by TRIZOL, treated with amplification-grade DNaseI (Invitrogen), and used for cDNA synthesis using SuperScript II (Invitrogen). To detect transcript covering the entire cluster, we designed primers corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ boundary of the cluster (mir-17–5p and mir-92a), as shown: CAAAGTGCTTACAGTGCAGGTAGT(mir-17–5p)GATGTGTGCATCTACTGCAGTGAGGGCACTTGTAGCATTATGCT-GACAGCTGCCTCGGTGGGAGCCACAGTGGGCGCTGCCTCGGGCG-GCACTGGCTGCGTCCAGTCGTCGGTCAGTCGGTCGCGGGGAGG-GCCTGCTGGTGCTGCGTGCTTTTTGTTCTAAGGTGCATCTAGTG-CAGATAGTGAAGTAGACTAGCATCTACTGCCCTAAGTGCTCCTTCTGGCATAAGAAGTTATGTCCTCATCCAATCCAAGTCAAGCAAGCATGTAGGGGTCTCTCCATAGTTGTGTTTGCAGCCCTCTGTTAGTTTTGCATAGTTGCACTACAAGAAGAATGTAGTTGTGCAAATCTATGCAAAACTGATGGTGGCCTGCTATTTACTTCAAGTGTTGTTTTTTTTTAAACTAATTTTGTATTTTTATTGTGTCGATGTAGAGCCTGCGTGGTGTGTGTGATGTGACAGCTTCTGTAGCAC[b]TAAAGTGCTTAT-AGTGCAGGTA(mir-20)GTGTGTAGCCATCTACTGCATTACGAGCACTT-AAAGTACTGCCAGCTGTAGAACTCCAGCCTCGCCTGGCCATCGCCCAGCCAACTGTCCTGTTATTGAGCACTGGTCTATGGTTAGTTTTGCAGGTTTGCATCCAGCTGTATAATATTCTGCTGTGCAAATCCATGCAAAACTGACTGTGGTGGTGAAAAGTCTGTAGAGAAGTAAGGGAAAATCAAACCCCTTTCTACACAGGTTGGGATTTGTCGCAATGCTGTGTTTCTCTGTATGG[b]TATTGCACTTGTCCCGGCCTGT(mir-92a). The cluster forward and reverse primers were 5′-CAAAGTGCTTACAGTGCAGGTAG-3′ and 5′-ACAGGCCGGGACAAGTGCAATA-3′, respectively. Because of nucleotide similarity between mir-17–5p and mir-20a (shown in bold in above sequence), the size of the PCR products is expected to be 314 and 814 bp. The following primers were used: GAPDH forward, 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGTGAGGGAGATGCTCAGTG-3′; Skp2 forward, 5′- ATCCCACATGGACTGCTCTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTTAAGTCGAGGCGGATGAG-3′.

Quantitative real-time PCR of p27 and primary miRNA of mir-17–92 cluster

The total RNA was extracted by TRIZOL and treated with DNaseI. cDNA was created using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). PCR analysis was performed by SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma, St Louis, MO) according to the manufacture's protocol using the ABI PRISM 7000 machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR primers were as follows: p27 forward primer, 5′-AGGGCCAACAGAACAGAAGA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CCAGATGGGGTGTCAGTTTT-3′; mir-17–92 primary transcript region forward primer, 5′-CAAAGTGCTTACAGTGCAGGTAG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TATCTGCACTAGATGCACCTTA-3′; mouse GAPDH forward primer, 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′- GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT-3′.

miRNA Northern blots

mRNA was isolated using a mirVanaTM miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, 20 μg total RNA was separated on 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, electrotransferred to GeneScreen Plus membranes (Ambion), UV cross-linked, and hybridized using UltraHyb-Oligo buffer (Ambion). Oligonucleotides complementary to mature miRNAs were end labeled using T4 Kinase (Invitrogen) and used as probes. Probe sequences were as follows: mir-17–5p, 5′- ACTACCTGCACTGTAAGCACTTTG-3′; mir-17–3p, 5′ -ACAAGTGCCCTCACTGCAGT-3′; mir-18a, 5′-TATCTGCACTAGATGCACCTTA-3′; mir-19a, 5′-TCAGTTTTGCATAGATTTGCACA-3′; mir-20a, 5′-CTACCTGCACTATAAGCACTTTA-3′; mir-92, 5′-ACAGGCCGGGACAAGTGCAATA-3′. 5S rRNA served as loading control.

Immunoblotting and antibodies

Lysates (50 μg) from cells lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation buffer were resolved on sodium-dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gels, and immunoblotted as described elsewhere.28 Antibodies to Fli-1, p-Akt, p-Erk, Akt, Erk, p27, Spi-1, β-actin, cyclin D1, and CDK2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Scanned images were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The intensity of the band was then normalized to β-actin. For each experiment, data were representative of 3 independent experiments.

Luciferase assays

The 3′-UTR of the p27 gene (nucleotide position 1101–3084, accession no. NM_009875) was isolated from NIH-3T3 cells by RT-PCR. To insert this fragment into the luciferase vector pGL3 (Promega, Madison, WI), an XbaI site was added to the 5′ end of the following primers: p27 UTR forward primer, 5′-TCTAGAACAGCTCCGGTGGGTTAATGAG-3′; p27 UTR reverse primer, 5′-TCTAGAGTGGTATTAGAGTCAGGGTCC-3′. The sequence of RT-PCR product was confirmed by sequencing. The experimental luciferase construct (pGL3-p27-UTR) was generated by ligating p27 UTR into the XbaI site of the pGL3 vector. pGL3-p27-UTR or the pGL3 vector (400 ng) was cotransfected with 80 ng pSV-β-galactosidase control plasmid (Promega) into NIH-3T3-mir-17–92 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). KH16 cells were electroporated (Gene Pulser II; Bio-Rad) using 625 V/cm and 900 μF capacitance with the same amount of pGL3 vector or pGL3-p27-UTR and pSV-[β]-galactosidase plasmid. For the HEK 293T experiment, pGL3 vector or pGL3-p27-UTR (400 ng) was cotransfected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 (400 ng) and pSV-[β]-galactosidase plasmid (80 ng) into HEK 293T cells. Luciferase assays were performed 48 hours after transfection using the Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to [β]-galactosidase expression driven by cotransfected pSV-[β]-galactosidase plasmid for each transfected well. Triplicate transfected wells were used for each group.

Results

Identification and isolation of a new proviral integration site (Fli-3) in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia cells

We have previously demonstrated that in 4 erythroleukemia cell lines KH9, KH11, KH14, and KH16, derived from p53 mutant mice, insertional activation of Fli-1 cannot be detected and none of these cell lines express a detectable level of Fli-1.11 Other oncogenes known to be activated in related erythroleukemias and myeloid leukemias, including Spi-1, Evi-1, c-myc, and Pim-1, were also shown not to be involved. In addition, it is unlikely that these erythroleukemias occurred spontaneously since these types of tumors have not been found in p53−/− mice.11 Given these results, it is possible that insertional activation or inactivation of a novel gene not previously implicated in erythroleukemia, may be responsible for the transformation of this subset of cells. Integrated proviruses and their junction fragments were isolated from the Epo-dependent cell line KH9-ED established from KH9 tumors that contained 3 copies of the integrated proviruses.11 Southern blot analysis using a genomic probe designated Fli-3 from one of the proviral integration sites, detected a common pattern of rearrangement in KH9 tumors and derivative Epo-dependent KH9-ED and Epo-independent KH9-EI cells (Figure 1A). The Fli-3 probe did not detect rearrangement in 2 other Fli-1–negative cell lines KH11 and KH14, but a 5- to 10-fold amplification of this locus was seen in the KH16 cell line (Figure 1A). These results show that in 50% of the Fli-1–negative cell lines, the Fli-3 locus was altered by either proviral integration or gene amplification. A similar examination of 2 other proviral integration sites isolated from KH9 tumors did not reveal a common insertion site and were not studied further.

Detection of Fli-3 locus and transcripts in cell lines that do not express Fli-1. (A) High-molecular-weight DNA from cell lines KH9-ED, KH9-EI, KH11, KH14, and KH16, and control BALB/C mouse spleen cells was digested with EcoR1 and analyzed by Southern blot using the Fli-3 probe. The arrow shows the position of the rearranged bands. Hybridization with a Fli-1–specific probe was used to show equal loading. The intensity of KH9-ED band was used as control (1.0). The intensity of other bands was compared with the control. (B) Expression of Fli-3 in erythroleukemia cell lines. RNA isolated from the indicated cell lines was hybridized with the Fli-3 probe. Hybridization of the same blot with a GAPDH probe was used to show equal loading. The intensity of KH11 band was used as control (1.0). (C) Expression of Fli-3 in various murine tissues. Total RNA (20 μg) was isolated from various tissues and subjected to Northern blot analysis using the Fli-3 probe. (D) Expression of Fli-3 in various cell lines. Total RNA isolated from fibroblasts (NIH-3T3), erythroleukemia cell lines (DP18–9, CB3, CB7), breast cancer cell line (EMT6), a B-lymphocytic leukemia cell line (B10), a thymoma cell line (Yab-3), and endothelial cell line (SVR) was hybridized to the Fli-3 probe. The 18S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used to show equal loading. The intensity of CB3 band was used as control (1.0). (E) Expression of Fli-3 in murine hematopoietic cell lineages. E indicates erythroid cells; Meg, megakaryocyte; Mac, macrophage; Neu, neutrophil; BFU-E, burst forming units–erythroid; CFU-E, colony forming units–erythroid; Mast, mast cells; B, B lymphocyte; T, T lymphocyte; and p, unipotent precursor cells of 7-day colonies. The left column of each blot contains pentapotent (E/Meg/Mac/Neu/Mast), tetrapotent, tripotent, bipotent, and unipotent precursor cell cDNAs. Middle and right columns contain unipotent precursor cell cDNAs (pMac, pNeu, pMeg) and samples from terminally maturing cells (E, Neu, Mast, Meg, T, B). S17 and 95/1.7 are cDNA isolated from the bone marrow–derived fibroblastic cell lines. Quantification of radioactive signal intensity is shown at the bottom. Fold changes shown are mean values derived from 3 experiments.

Detection of Fli-3 locus and transcripts in cell lines that do not express Fli-1. (A) High-molecular-weight DNA from cell lines KH9-ED, KH9-EI, KH11, KH14, and KH16, and control BALB/C mouse spleen cells was digested with EcoR1 and analyzed by Southern blot using the Fli-3 probe. The arrow shows the position of the rearranged bands. Hybridization with a Fli-1–specific probe was used to show equal loading. The intensity of KH9-ED band was used as control (1.0). The intensity of other bands was compared with the control. (B) Expression of Fli-3 in erythroleukemia cell lines. RNA isolated from the indicated cell lines was hybridized with the Fli-3 probe. Hybridization of the same blot with a GAPDH probe was used to show equal loading. The intensity of KH11 band was used as control (1.0). (C) Expression of Fli-3 in various murine tissues. Total RNA (20 μg) was isolated from various tissues and subjected to Northern blot analysis using the Fli-3 probe. (D) Expression of Fli-3 in various cell lines. Total RNA isolated from fibroblasts (NIH-3T3), erythroleukemia cell lines (DP18–9, CB3, CB7), breast cancer cell line (EMT6), a B-lymphocytic leukemia cell line (B10), a thymoma cell line (Yab-3), and endothelial cell line (SVR) was hybridized to the Fli-3 probe. The 18S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used to show equal loading. The intensity of CB3 band was used as control (1.0). (E) Expression of Fli-3 in murine hematopoietic cell lineages. E indicates erythroid cells; Meg, megakaryocyte; Mac, macrophage; Neu, neutrophil; BFU-E, burst forming units–erythroid; CFU-E, colony forming units–erythroid; Mast, mast cells; B, B lymphocyte; T, T lymphocyte; and p, unipotent precursor cells of 7-day colonies. The left column of each blot contains pentapotent (E/Meg/Mac/Neu/Mast), tetrapotent, tripotent, bipotent, and unipotent precursor cell cDNAs. Middle and right columns contain unipotent precursor cell cDNAs (pMac, pNeu, pMeg) and samples from terminally maturing cells (E, Neu, Mast, Meg, T, B). S17 and 95/1.7 are cDNA isolated from the bone marrow–derived fibroblastic cell lines. Quantification of radioactive signal intensity is shown at the bottom. Fold changes shown are mean values derived from 3 experiments.

Isolation of transcripts for Fli-3 and analysis of the expression pattern of Fli-3

To isolate the relevant transcripts for this locus, the Fli-3 probe was used for Northern blot analysis of RNAs isolated from a panel of erythroleukemia cell lines. As shown in Figure 1B, using the Fli-3 probe, we detected a major transcript of 3.5 kb and a minor transcript of 2 kb with higher expression in KH9 and KH16 cells. The expression of these mRNAs was 2- to 4-fold higher in KH9-ED and KH9-EI cells and more than 5-fold higher in KH16 cells compared with KH11 and KH14 cells. To investigate whether expression of the Fli-3 transcripts is tissue restricted, we examined its expression in various cell lines and murine organs. Examination of murine tissues revealed insignificant Fli-3 levels, except for low expression in spleen (Figure 1C). Further analysis of additional mouse cell lines of various origins revealed Fli-3 expression in erythroleukemia cell lines CB7, CB3, and DP18–9, and breast cancer cell line EMT6. Fli-3 expression was not detected in B-lymphocytic leukemia cell line B10, thymoma cell line Yab-3, NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, and the endothelial cell line SVR (Figure 1D). To explore further the expression pattern of Fli-3, a lineage blot of hematopoietic cells was hybridized with the Fli-3 probe. Different levels of Fli-3 transcript were detected in almost all the hematopoietic cell lineages (Figure 1E). However, Fli-3 expression was negligible in NIH-3T3 cells and 2 other bone marrow–derived fibroblastic cell lines, S17 and 95.1.7.

Characterization of Fli-3 locus and its candidate gene

Using the Fli-3 probe, several clones from cDNA libraries constructed from KH9 and KH16 cell lines were isolated. Following sequencing of the cDNA insert from these clones, a 2.2-kb sequence corresponding to the Fli-3 transcript containing a polyA termination site was obtained. The Fli-3 sequence is identical to an EST (GenBank accession no. AK053349.1) with unknown function and no ORF. The Fli-3 locus is located on the mouse chromosome 14 and human chromosome 13q13-q32. Recently, a gene corresponding to the 13q31 locus (designated C13orf25) has been identified that contains 7 miRNAs (mir-17–5p, mir-17–3p, mir-18, mir-19a, mir-20, mir-19b, and mir-92a), designated the mir-17–92 cluster.21 Further comparison of this sequence with the Mus musculus BAC clone RP23–132K20 from chromosome 14 (GenBank accession no. AC163295) revealed that Fli-3 is homologous to C13orf25. Alignment of Fli-3 and its human orthologue C13orf25 by mVista plot29 revealed extensive sequence conservation only within the mir-17–92 polycistron and its immediate flanking sequence (Figure 2A,B). Integration of the F-MuLV provirus was located 298-bp upstream of this cluster (Figure 2A).

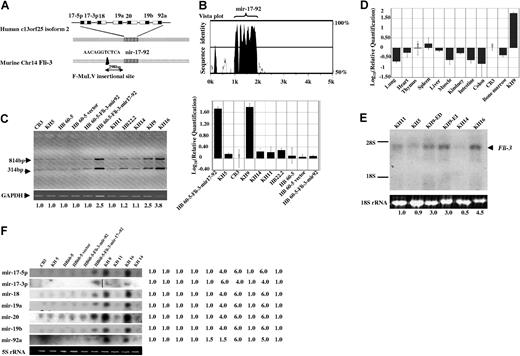

The expression analysis of the mir-17–92 cluster in different cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of the Fli-3 gene containing polycistronic miRNA clusters. The striped box (▥) shows the homology region of the murine Fli-3 gene and human C13orf25 gene. The black box (■) shows the region of mature miRNA in the mir-17–92 cluster. The arrow shows the location of the proviral integration site located 298-bp upstream from the cluster. (B) The homology between human and mouse Fli-3 using mVista plot. The high homology region is localized within the mir-17–92 region of both Fli-3 and human C13orf25. (C) Pri-miRNA expression levels in erythroleukemia cell lines were detected by RT-PCR. The size of PCR products is expected to be 314 and 814 bp (for details, see “Materials and methods”). GAPDH was used as loading control. The intensity of CB3 band was used as control (1.0). Fold changes shown at the bottom are mean values derived from 3 experiments. The real-time PCR results are shown at the right panel. The expression of mir-17–92 in CB3 cells was used for calibration. (D) The relative quantities of mir-17–92 expression in normal murine organs detected by the real-time PCR. The expression of mir-17–92 in CB3 cells was used for calibration. Error bars in panels C and D are SD. (E) Pri-miRNA expression levels in erythroleukemia cell lines was detected by Northern blot using mir-17–92 cluster probe derived from the 814-bp PCR product shown in Figure 2C. The 18S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used as loading control. The intensity of KH11 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (F) Mature miRNA expression was examined in the indicated cell lines by Northern blot analysis using specific oligonucleotide probes corresponding to each mature miRNA from the mir-17–92 cluster. 5S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used as a loading control. A vertical line was inserted to show where a gel lane was cut. The intensity of CB3 was used as control (1.0).

The expression analysis of the mir-17–92 cluster in different cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of the Fli-3 gene containing polycistronic miRNA clusters. The striped box (▥) shows the homology region of the murine Fli-3 gene and human C13orf25 gene. The black box (■) shows the region of mature miRNA in the mir-17–92 cluster. The arrow shows the location of the proviral integration site located 298-bp upstream from the cluster. (B) The homology between human and mouse Fli-3 using mVista plot. The high homology region is localized within the mir-17–92 region of both Fli-3 and human C13orf25. (C) Pri-miRNA expression levels in erythroleukemia cell lines were detected by RT-PCR. The size of PCR products is expected to be 314 and 814 bp (for details, see “Materials and methods”). GAPDH was used as loading control. The intensity of CB3 band was used as control (1.0). Fold changes shown at the bottom are mean values derived from 3 experiments. The real-time PCR results are shown at the right panel. The expression of mir-17–92 in CB3 cells was used for calibration. (D) The relative quantities of mir-17–92 expression in normal murine organs detected by the real-time PCR. The expression of mir-17–92 in CB3 cells was used for calibration. Error bars in panels C and D are SD. (E) Pri-miRNA expression levels in erythroleukemia cell lines was detected by Northern blot using mir-17–92 cluster probe derived from the 814-bp PCR product shown in Figure 2C. The 18S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used as loading control. The intensity of KH11 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (F) Mature miRNA expression was examined in the indicated cell lines by Northern blot analysis using specific oligonucleotide probes corresponding to each mature miRNA from the mir-17–92 cluster. 5S rRNA from the ethidium bromide–stained gel was used as a loading control. A vertical line was inserted to show where a gel lane was cut. The intensity of CB3 was used as control (1.0).

To investigate whether the mir-17–92 polycistron is the candidate gene of the Fli-3 locus activated by F-MuLV proviral integration, expression of the mir-17–92 cluster was compared between Fli-3–overexpressing cell lines and those without alteration at the Fli-3 locus. miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II as long primary transcripts (pri-miRNA) and undergo sequential processing to produce mature miRNAs.30,31 To confirm that the pri-miRNA of the mir-17–92 cluster is highly expressed in Fli-3–overexpressing cell lines, primers were designed to amplify the whole cluster (mir-17–5p to mir-92). Because of nucleotide similarity between mir-17–5p and mir-20, the size of the detected PCR products was 314 and 814 bp, respectively (Figure 2C) (for details, see “Materials and methods”). Furthermore, the expression was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2C,D). Results show low levels of Fli-3 expression in the spleen and minimal levels in the thymus compared with the expression in CB3 cells (Figure 2D). These results using quantitative real-time PCR are consistent with the expression pattern seen by Northern blot analysis using the Fli-3 probe (Figure 1C).

The 814-bp PCR product designated as the cluster probe was also used as a probe to detect the expression of pri-miRNA by Northern blot analysis in a panel of erythroleukemia cell lines (Figure 2E). The 3.5-kb band detected by the cluster probe corresponds to the major transcript detected by the Fli-3 probe (Figure 1B). Northern blot analysis was also used to examine the expression of mature miRNAs derived from the mir-17–92 cluster (Figure 2F). Comparison of cell lines carrying a Fli-3 overexpression (KH9 and KH16) with other F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia cells showed an increase in the levels of pri-miRNA and mature miRNAs in KH9 and KH16 cells. Furthermore, the increase in pri-miRNA expression paralleled the increase in mature miRNA derived from the polycistron. In contrast, other cell lines without Fli-3 overexpression showed low expression of the pri-miRNA as well as its mature miRNA (Figure 2C-E). The increased expression of mir-17–92 correlates with the presence of a Fli-3 transcription unit containing no ORF, and indicates that this miRNA cluster is likely the Fli-3 gene. These data suggest that this novel integration site, Fli-3, actually encodes the mir-17–92 cluster.

Fli-3 overexpression switches Epo responsiveness of erythroid cells from differentiation to proliferation

The Fli-3 overexpression data prompted us to hypothesize that mir-17–92 may contribute to erythroleukemia progression. Erythroleukemic cells with an insertional activation at the Fli-3 locus become Epo dependent. This raises the possibility that miRNA encoded by this locus, like Fli-1 insertional activation,5 may alter the Epo signal transduction pathway. To directly test this hypothesis, HB60–5 cells that proliferate in the presence of SCF and Epo, but undergo differentiation by Epo alone,32 were infected with a retrovirus carrying a truncated cluster comprising only mir-92 (hereafter Fli-3 mir-92) or the entire mir-17–92 cluster (hereafter Fli-3 mir-17–92) (Figure 3A). The HB60–5 cells infected with these retroviruses produce the appropriate miRNAs, as assessed by RT-PCR and Northern blotting (Figures 2C,F and 3A). Ectopic expression of either Fli-3-mir-92 or Fli-3-mir-17–92 in HB60–5 cells alters the normal response of these cells to Epo, promoting their self-renewal rather than their maturation (Figure 3B,C). Epo-induced proliferation is higher in Fli-3-mir-17–92–infected cells than Fli-3-mir-92–infected cells (Figure 3C). Accordingly, the block in differentiation as measured by globin expression is more significant in the Fli-3-mir-17–92–expressing HB60–5 cells than that in Fli-3-mir-92–expressing cells (Figure 3B).

Effect of overexpression of Fli-3 on the differentiation and proliferation of HB60–5 cells by Epo. (A) Schematic diagram of the Fli-3-mir-92 and Fli-3-mir-17–92 expression vectors. The right panel shows the ectopic expression of Fli-3 in HB60–5 cells and NIH-3T3 cells detected by Northern blot using the Fli-3 probe. (B) Fli-3 ectopic expression blocks differentiation of HB60–5 cells. HB60–5 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-92, Fli-3-mir-17–92, or empty vector retrovirus were grown in medium containing 1 U/mL Epo and subjected to Northern blot analysis using the Fli-3 and α-globin probe. Hybridization of the same blot with a GAPDH probe was used to show equal loading. (C) Ectopic expression of Fli-3 promotes proliferation of HB60–5 cells. Triplicate cultures of HB60–5 cells (104) infected with either Fli-3-mir-92, Fli-3-mir-17–92, or empty vector were grown in media containing Epo (1 U/mL) and the number of viable cells was determined at indicated days. Error bars are SD.

Effect of overexpression of Fli-3 on the differentiation and proliferation of HB60–5 cells by Epo. (A) Schematic diagram of the Fli-3-mir-92 and Fli-3-mir-17–92 expression vectors. The right panel shows the ectopic expression of Fli-3 in HB60–5 cells and NIH-3T3 cells detected by Northern blot using the Fli-3 probe. (B) Fli-3 ectopic expression blocks differentiation of HB60–5 cells. HB60–5 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-92, Fli-3-mir-17–92, or empty vector retrovirus were grown in medium containing 1 U/mL Epo and subjected to Northern blot analysis using the Fli-3 and α-globin probe. Hybridization of the same blot with a GAPDH probe was used to show equal loading. (C) Ectopic expression of Fli-3 promotes proliferation of HB60–5 cells. Triplicate cultures of HB60–5 cells (104) infected with either Fli-3-mir-92, Fli-3-mir-17–92, or empty vector were grown in media containing Epo (1 U/mL) and the number of viable cells was determined at indicated days. Error bars are SD.

We have previously demonstrated that the erythroblastic cell line HB60–5 overexpressing Fli-1 undergoes Epo-induced proliferation associated with activation of the Ras pathway and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K).32 To investigate whether Fli-3 inhibits the differentiation of HB60–5 cells through the same mechanism, the expression of the target proteins for Ras (phospho-Erk) and PI3K (phospho-Akt) in response to Epo stimulation was examined. These experiments revealed a significant increase in the expression of their target proteins in response to Epo stimulation in cells infected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 compared with cells infected with empty vector (Figure 4A). An increase was not observed in HB60–5 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-92 (data not shown). These results suggest that the transforming ability of Fli-3 may be attributed to its role in the responsiveness of erythroblasts to Epo.

Identification of the potential downstream effectors of the mir-17–92 cluster in erythroleukemia cells. (A) The expression of phospho-Akt and phospho-Erk was determined by Western blot in HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92 or empty vector in response to Epo stimulation. Cells were grown without growth factors for 6 hours and then stimulated with Epo (1 U/mL) for 10 minutes. The controls are HB60–5 cells cultured in media containing Epo and SCF. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). (B) Expression analysis of Spi-1, Fli-1, and p27 protein in a panel of erythroleukemia cells. The indicated cells were lysed and Western blotted with Spi-1–, Fli-1–, or p27-specific antibodies. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). (C) Expression analysis of p27 protein in HB60–5 cells overexpressing Fli-1. The blot was stripped and rehybridized with β-actin antibody to demonstrate the equal loading. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the right side.

Identification of the potential downstream effectors of the mir-17–92 cluster in erythroleukemia cells. (A) The expression of phospho-Akt and phospho-Erk was determined by Western blot in HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92 or empty vector in response to Epo stimulation. Cells were grown without growth factors for 6 hours and then stimulated with Epo (1 U/mL) for 10 minutes. The controls are HB60–5 cells cultured in media containing Epo and SCF. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). (B) Expression analysis of Spi-1, Fli-1, and p27 protein in a panel of erythroleukemia cells. The indicated cells were lysed and Western blotted with Spi-1–, Fli-1–, or p27-specific antibodies. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). (C) Expression analysis of p27 protein in HB60–5 cells overexpressing Fli-1. The blot was stripped and rehybridized with β-actin antibody to demonstrate the equal loading. The intensity of HB60–5 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the right side.

Identification of the potential downstream effectors of Fli-3 overexpression

To study the functional consequences of induction of the mir-17–92 cluster, we examined the expression of known genes that have been previously associated with erythroid transformation. Although there was no expression of Fli-1 or Spi-1 in KH9 and KH16 cell lines that overexpress Fli-3, the expression of Spi-1 was dramatically increased in HB60–5 cells infected with retrovirus bearing Fli-3-mir-17–92 compared with the cells infected with vector alone or with Fli-3-mir-92 retroviruses (Figure 4B).

Another protein previously implicated in erythroid differentiation is the cell-cycle inhibitor p27 (Kip1).33 This protein has been shown to be up-regulated during erythroid differentiation leading to cell-cycle arrest.33 We have shown that ectopic expression of Fli-3-mir-17–92 in HB60–5 cells results in significant down-regulation of p27 protein (Figure 4B). However, p27 down-regulation was not significant in HB60–5 cells infected with the Fli-3-mir-92 retrovirus. p27 protein levels were also low in other erythroleukemia cell lines with or without Fli-1 activation (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we showed that overexpression of Fli-1 in HB60–5 cells, like overexpression of Fli-3 in these cells, suppressed p27 expression (Figure 4C), but at lower levels. Therefore, Fli-1 and Fli-3 may share a similar mechanism of p27 suppression during erythroblast transformation. Moreover, ectopic expression of the Fli-3-mir-17–92 gene, but not the Fli-3-mir-92 gene, in NIH-3T3 cells also resulted in p27 protein down-regulation (Figure 5A). These results suggest p27 is a potential target of Fli-3 mir-17–92–mediated erythroid transformation.

p27 protein is down-regulated in the Fli-3–infected cells. (A) Protein isolated from NIH-3T3 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or empty vector was subjected to Western blot analysis using p27 antibody. The intensity of NIH3T3 band was used as control (1.0). (B,C) RNA isolated from NIH-3T3 cells or HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or vector was subjected to PCR analysis using the primers for both p27 and GAPDH. The intensity of NIH3T3 (B) or HB60–5 vector (C) band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (D) RNA isolated from NIH-3T3 cells and HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or vector control was subjected to real-time PCR analysis using the primers for both p27 and GAPDH. The expression of p27 in HB60–5 cells was used for calibration. Error bars are SD.

p27 protein is down-regulated in the Fli-3–infected cells. (A) Protein isolated from NIH-3T3 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or empty vector was subjected to Western blot analysis using p27 antibody. The intensity of NIH3T3 band was used as control (1.0). (B,C) RNA isolated from NIH-3T3 cells or HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or vector was subjected to PCR analysis using the primers for both p27 and GAPDH. The intensity of NIH3T3 (B) or HB60–5 vector (C) band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (D) RNA isolated from NIH-3T3 cells and HB60–5 cells infected with either Fli-3-mir-17–92, Fli-3-mir-92, or vector control was subjected to real-time PCR analysis using the primers for both p27 and GAPDH. The expression of p27 in HB60–5 cells was used for calibration. Error bars are SD.

To verify whether the expression of p27 is altered at the transcriptional or translational level, p27 mRNA expression in HB60–5 or NIH-3T3 cells infected with the vector alone was compared with that in HB60–5 or NIH-3T3 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 or Fli-3-mir-92 retroviruses. We showed that Fli-3-mir-17–92 overexpression down-regulates p27 at the protein level without influencing the mRNA expression (Figure 5A–C). This result was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 5D). Therefore, the Fli-3-mir-17–92 gene regulates the expression of p27 at the posttranslational level. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination of p27 have been shown to play important roles in the degradation of p27 at the posttranslational level.34 Proteins with these functions are potential targets of the mir-17–92 cluster. Therefore the expression of the ubiquitin protein ligase SCF (Skp2), phospho-Akt, CDK2, cyclin E, and cyclin D1, which play important roles in degradation of p27,35,36 was examined. The expression of these proteins, detected by RT-PCR or Western blot analysis, remained unchanged following Fli-3 overexpression, and their expression in HB60–5 cells was the same as that in NIH-3T3 cells (Figure 6A), with the exception that there was no cyclin D1 expression in HB60–5 cells (data not shown).

Investigation of the mechanism of p27 regulation by Fli-3 mir-17–92. (A) Expression analysis of the proteins associated with p27 ubiquitination (Skp2, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and CDK2) in NIH-3T3 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 and the control groups. The intensity of NIH3T3 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (B) Posttranscriptional regulation of p27 by mir-17–92 cluster through a specific binding to the p27 3′UTR was examined using luciferase assay. The 3′UTR of p27 was cloned into pGL3 vector and designated pGL3-p27-UTR. NIH-3T3-mir-17–92 cells were transfected with pGL3-p27-UTR (experimental group, Ex) or pGL3 control vector (control group, Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. 293T cells were cotransfected with either pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or vector alone (Clt) and either Fli-3 mir-17–92 or vector alone and used to determine the luciferase activity. (C) KH16 cells were electroporated with the same amount of pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or pGL3 vector (Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. [β]-Galactosidase plasmid was also included in the transfections and firefly luciferase activity was normalized to [β]-galactosidase expression. Error bars are SD.

Investigation of the mechanism of p27 regulation by Fli-3 mir-17–92. (A) Expression analysis of the proteins associated with p27 ubiquitination (Skp2, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and CDK2) in NIH-3T3 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 and the control groups. The intensity of NIH3T3 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (B) Posttranscriptional regulation of p27 by mir-17–92 cluster through a specific binding to the p27 3′UTR was examined using luciferase assay. The 3′UTR of p27 was cloned into pGL3 vector and designated pGL3-p27-UTR. NIH-3T3-mir-17–92 cells were transfected with pGL3-p27-UTR (experimental group, Ex) or pGL3 control vector (control group, Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. 293T cells were cotransfected with either pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or vector alone (Clt) and either Fli-3 mir-17–92 or vector alone and used to determine the luciferase activity. (C) KH16 cells were electroporated with the same amount of pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or pGL3 vector (Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. [β]-Galactosidase plasmid was also included in the transfections and firefly luciferase activity was normalized to [β]-galactosidase expression. Error bars are SD.

To determine whether p27 is directly regulated by mir-17–92, a luciferase reporter construct containing a portion of the p27 3′-UTR was generated. When this construct was introduced into NIH-3T3- Fli-3-mir-17–92 cells or cotransfected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 into HEK 293T cells, no significant reduction in luciferase activity was observed compared with the control-transfected cells (Figure 6B). This result is consistent with the target prediction analysis37 that also shows no significant homology between p27 3′ UTR and the Fli-3-mir-17–92 sequence (data not shown). We also investigated the possibility that the erythroid environment may be important for the regulation of the p27 3′-UTR by the mir-17–92 cluster. Electroporation of a p27 3′ UTR luciferase construct or a control luciferase vector into erythroleukemia cell line KH16 with mir-17–92–overexpressing cells, however, did not show any difference in the luciferase activity (Figure 6C).

Discussion

In this study, we have identified a novel gene, Fli-3, whose expression is activated by either insertional mutagenesis or gene amplification, in a unique class of F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia cell lines that do not express Fli-1. Analysis has confirmed that the Fli-3 transcript is a murine homolog of the recently identified human C13orf25 gene corresponding to 13q31, a region that is frequently amplified in several types of tumors including lymphoma and lung cancer.18,21,38 Alignment of Fli-3 and C13orf25 revealed extensive sequence conservation within the mir-17–92 polycistron and its immediate flanking sequence. In addition, the data presented here show an increase in the expression levels of the mir-17–92 cluster and the mature miRNAs encoded by this cluster in erythroleukemia cell lines with Fli-3 overexpression. Recently, this mir-17–92 cluster has been shown to function as an oncogene since its enforced expression accelerates the development of B-cell lymphoma in a transgenic mouse model overexpressing c-myc.22

The conservation of miRNA among species suggests a conserved biologic function. We postulated that increased expression of Fli-3 encoding the mir-17–92 cluster contributed to erythroleukemia. To test this hypothesis, the mir-17–92 cluster was overexpressed in erythroblastic cell line HB60–5. The ectopic expression of this cluster switched Epo-induced differentiation to Epo-induced proliferation, which also occurs with overexpression of Fli-1.32 These results suggest that Fli-3–induced inhibition of terminal differentiation specifically results from its ability to impair Epo-EpoR signaling events, similar to Fli-1. Interestingly, when a transcript expressing only one of the miRNAs, mir-92a, was introduced in HB60–5 cells, the levels of Epo-induced proliferation and the block in differentiation were not as efficient as that observed in the cells expressing the entire cluster. These observations indicate that the 7 miRNAs encoded by this polycistron may cooperate to transform erythroblasts.

While erythroid cell lines that have acquired Fli-3 alteration are negative for Fli-1 expression, overexpression of either gene appears to block differentiation and alters Epo responsiveness of these cells through the activation of the Ras and PI3K pathways. Previous observations suggested that Fli-1 might regulate downstream target genes responsible for Epo-induced proliferation of erythroid progenitors.32 Such targets for Fli-1, however, have yet to be identified and Fli-3-mir-17–92 may also regulate an overlapping target gene(s) leading to erythroid transformation. Therefore, characterization of the target genes for both Fli-1 and Fli-3 could eventually lead to a better understanding of the mechanism by which these genes are involved in malignant transformation.

The key to understanding the role of this polycistron in cancer will be in the identification and validation of the critical targets responsible for the oncogenic effects observed when its expression is altered. In contrast to plants, where miRNAs are extensively base-paired with their target mRNAs, near-perfect complementarities between miRNAs and protein-coding genes almost never exist in mammals. This feature makes it difficult to directly pinpoint relevant miRNA downstream targets in a given tissue.12 The experiments described here indicate that miRNAs within the mir-17–92 cluster function as proto-oncogenes, possibly by targeting regulatory factors capable of controlling the protein expression of genes that direct cellular proliferation and differentiation. The examination of several known regulatory factors associated with erythroid differentiation and proliferation has identified a significant decrease in the level of p27 (Kip1) in erythroleukemic cells overexpressing Fli-3-mir-17–92. Such a decrease in p27 was also seen in fibroblasts (NIH-3T3) overexpressing the cluster. We have previously shown that p27 is up-regulated during erythroid differentiation.33 In addition, Fli-3 overexpression in HB60–5 cells leads to a decrease in p27 expression that also occurs with Fli-1 overexpression, indicating that the down-regulation of this cell-cycle inhibitor by Fli-3 could be one of the pathways leading to transformation. We have shown that the mir-17–92 cluster does not target p27 directly for down-regulation. Moreover, none of the known pathways that regulate p27 was altered as a result of mir-17–92 overexpression. Additional investigations to elucidate the function of the mir-17–92 cluster and mechanisms underlying p27 down-regulation will provide insight into the role of mir-17–92 in malignant transformation.

Since Fli-1 is a major site of insertional activation in F-MuLV–induced erythroleukemia3 and Spi-1 is a major insertional site in spleen focus-forming virus-induced erythroleukemia,39 these 2 Ets family members are the 2 vital factors responsible for the pathogenesis of Friend disease.8 Due to the fact that both Fli-1 and Spi-1 share a common mechanism for erythroid transformation, we investigated the relationship between these 2 factors and Fli-3. While Fli-1 and Spi-1 expression was undetectable in both KH9 and KH16 cells overexpressing Fli-3, ectopic expression of the mir-17–92 cluster in HB60–5 cells significantly increased Spi-1 expression. In agreement with this result, a previous study has demonstrated that overexpression of Spi-1 in a transgenic mouse model blocks differentiation and induces Epo-dependent proliferation of erythroblasts.40 Thus, high Spi-1 expression and low p27 expression in HB60–5 cells may be responsible for the block in differentiation in these cells. Since Spi-1 up-regulation was observed only in HB60–5 cells, perhaps the function of the mir-17–92 cluster is dependent on the cell types in which these miRNAs are expressed and the presence of cell-specific mRNA targets.

In conclusion, we have identified the mir-17–92 cluster as the candidate gene for the new F-MuLV integration site designated Fli-3. Our study demonstrated that the mir-17–92 cluster was activated through retroviral insertional mutagenesis. This highlights the relevance of retrovirus-induced neoplasia and the importance of searching for proviral integration sites for the discovery of new classes of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. Furthermore, our data also indicate that the miRNA cluster inhibits erythroid differentiation and promotes erythroid proliferation by interfering with the Epo-EpoR pathway and is involved in the induction of erythroleukemia. Thus far, our results presented provide the evidence to suggest that Fli-3 is a novel oncogene participating in the development of murine erythroleukemia through an as-yet-unknown mechanism involving p27 regulation and the Epo-EpoR pathway. Moreover, Fli-3 was also shown to be expressed in various hematopoietic lineages, indicating the importance of miRNA in hematopoiesis. We envision that further study of Fli-3 through this well-established animal model of leukemogenesis should ultimately lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in miRNA function during the processes of malignant transformation and regulation of normal hematopoiesis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Y.B.-D. is supported by grants from Terry Fox Foundation of Canada through NCIC and Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada (LLSC).

We thank Drs Michael Archer and Yuval Shaked, Mr Mehran Haeri, and Miss Laura Vecchiarelli for input and critical reading of the paper.

Authorship

Contribution: J.-W.C. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; Y.-J.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, and performed the experiments presented in Figures 1 and 3; A.S. was involved in isolation of the Fli-3 locus from cDNA library and performed experiments presented in Figure 1; J.B. isolated the sequence of the Fli-3 locus from a Mus musculus bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and compared the sequence of the Fli-3 region with GenBank; Y.-H.T. was involved in isolation of the Fli-3 locus from a genomic library; M.P. was involved in generation of the Fli-3 microRNA schematic expression pattern (Figure 2A); C.M. performed the experiment presented in Figure 4A; N.I. has provided us with the blots of the murine hematopoietic cell lineage and was involved in slot hybridization and analysis of the experiment presented in Figure 1E; G.-J.W. was involved in supporting, designing, and providing constructive input on the outcome of this project and reviewing the paper; Y.B.-D. is principal investigator who was involved in designing the experiments and analyzing the overall data presented in this study. J.-W.C., Y.-J.L., and A.S. contributed equally to this study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yaacov Ben-David, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Division of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Research Bldg, Rm S-216, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5, Canada; e-mail:bendavid@sri.utoronto.ca.

![Figure 6. Investigation of the mechanism of p27 regulation by Fli-3 mir-17–92. (A) Expression analysis of the proteins associated with p27 ubiquitination (Skp2, p-Akt, cyclin D1, and CDK2) in NIH-3T3 cells infected with Fli-3-mir-17–92 and the control groups. The intensity of NIH3T3 band was used as control (1.0). Mean fold changes are shown at the bottom. (B) Posttranscriptional regulation of p27 by mir-17–92 cluster through a specific binding to the p27 3′UTR was examined using luciferase assay. The 3′UTR of p27 was cloned into pGL3 vector and designated pGL3-p27-UTR. NIH-3T3-mir-17–92 cells were transfected with pGL3-p27-UTR (experimental group, Ex) or pGL3 control vector (control group, Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. 293T cells were cotransfected with either pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or vector alone (Clt) and either Fli-3 mir-17–92 or vector alone and used to determine the luciferase activity. (C) KH16 cells were electroporated with the same amount of pGL3-p27-UTR (Ex) or pGL3 vector (Clt) and subjected to luciferase assay. [β]-Galactosidase plasmid was also included in the transfections and firefly luciferase activity was normalized to [β]-galactosidase expression. Error bars are SD.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/110/7/10.1182_blood-2006-10-053850/2/m_zh80190707850006.jpeg?Expires=1769136824&Signature=QpbmCG8D0GIXOh6HE18qqX-ZkbjCewYf4B3HD94RpiHTfEzcAiFnOqhg-a9tbtQvthmx7eK2hryPSleS7j6tmL75n5h14uB9cr4u2U~1L8hLimm9nyBfJiwtlbMAZ1MBnwdF0agwqZFunpjeQOBMcmsDNUw96dXSyPtVtO6yJDXXPhzmAUFGA-4UeELBBZ8VYSMAAkvh1zInI60PQJ8BfxeqIKFBppgTA93ytt6nOUKqmqW1tkj8KbUcFYlYFWxZjp9acDZCwrMPavBBX2A2DjT0FKyZKmY5JoUFFdYFit~owedmqCFbBPu798rrz2ZiqjOu99QZpEP69xMKrE-Rbw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal