Fetal loss in patients with antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies has been ascribed to thrombosis of placental vessels. However, we have shown that inflammation, specifically activation of complement with generation of the anaphylotoxin C5a, is an essential trigger of fetal injury. In this study, we analyzed the role of the procoagulant molecule tissue factor (TF) in a mouse model of aPL antibody–induced pregnancy loss. We found that either blockade of TF with a monoclonal antibody in wild-type mice or a genetic reduction of TF prevented aPL antibody–induced inflammation and pregnancy loss. In response to aPL antibody–generated C5a, neutrophils express TF potentiating inflammation in the deciduas and leading to miscarriages. Importantly, we showed that TF in myeloid cells but not fetal-derived cells (trophoblasts) was associated with fetal injury, suggesting that the site for pathologic TF expression is neutrophils. We found that TF expression in neutrophils contributes to respiratory burst and subsequent trophoblast injury and pregnancy loss induced by aPL antibodies. The identification of TF as an important mediator of C5a-induced oxidative burst in neutrophils in aPL-induced fetal injury provides a new target for therapy to prevent pregnancy loss in the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Introduction

Thrombosis and inflammation are linked in many clinical conditions.1 Tissue factor (TF), the major cellular initiator of the coagulation protease cascade, plays important roles in both thrombosis and inflammation.2 The coagulation cascade is initiated by the complex of TF and factor VIIa (FVIIa). The TF:FVIIa complex activates its substrates factor X and factor IX by limited proteolysis. Activated FX (FXa) then converts prothrombin to thrombin, which cleaves fibrinogen and activates platelets leading to the formation of a hemostatic plug. TF also contributes to inflammation. TF complexes (TF:FVIIa and TF:FVIIa:FXa) induce the expression of TNF-α, interleukins, and adhesion molecules by cleaving protease activated receptors (PARs).3,–5 Monocytes from patients with antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies express TF and in vitro experiments showed that monocytes incubated with aPL antibodies express TF.6,7 A variety of inflammatory stimuli, including mitogens, bacterial cell products, components of the complement system, and cytokines, is known to induce the expression of TF on the surface of endothelial cells, monocytes, and neutrophils.8,9 TF expression on these cells is a characteristic feature of acute and chronic inflammation in conditions such as sepsis, atherosclerosis, Crohn disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and transplant rejection reactions.10,,,–14 TF on monocytes and synovial cells promotes leukocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration, potentiating inflammation in joints,15 while decreased TF activity abrogates the systemic expression of inflammatory mediators in several animal models.16,17

The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is considered a thrombophilic disorder. However, animal studies from our laboratory have shown the importance of inflammation in the pathogenesis of aPL-induced pregnancy loss, a common complication in APS.18,19 Using a mouse model of APS, we demonstrated that complement activation, through the action of anaphylotoxin C5a, promotes neutrophil infiltration into the decidua leading to fetal death.19 Recently, human studies showed that inflammation in the placenta may contribute to APS pregnancy complications, reinforcing this new concept of the antiphospholipid syndrome as an inflammatory disorder.20 Growing evidence from studies of other coagulation-related disorders suggests the presence of an amplification network in which inflammatory mediators activate the coagulation system and, in turn, coagulation factors enhance inflammatory reactions.1

The objective of this study was to determine whether and how TF contributes to fetal loss in a mouse model of APS and define the mediators leading to fetal death.

Materials and methods

Transgenic mice

C5a receptor (C5aR)– and C3aR-deficient mice, generated by homologous recombination technology, were obtained from Dr Craig Gerard, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.21 C5-deficient (B10.D2.osn) and C5-sufficient (B10D2.nsn) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). C6-deficient mice derived from a Peruvian strain backcrossed with C3H/He were generously provided by B.P. Morgan (School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom). Low TF mice were generated as described22 and express very low levels of human TF (hTF) from a transgene in the absence of murine TF (mTF−/−, hTF+). mTF+/−, hTF+ mice crossed with mTF+/−, hTF+ mice were used as controls. TFflox/flox mice were generated from targeted embryonic stem cells.23 The TF gene was selectively deleted in myeloid cells by crossing TFflox/flox mice with mice containing a LysM-Cre transgene, which directs constitutive expression of the Cre recombinase to myeloid cells.24 C3H/HeJ defective lipopolysaccharide (LPS) response mice (Tlr4Lps-d) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. All the genetically engineered mice studied have been backcrossed into their respective strains for more than 6 generations.

Preparation of antibodies for in vivo studies

Human IgG–containing aPL antibodies (aPL-IgG) were obtained from patients with APS (characterized by high titer aPL antibodies [> 140 GPL:IgG phospholipid units], thromboses, and/or pregnancy losses). Normal human IgG (NH-IgG) was obtained from healthy nonautoimmune individuals. Mouse monoclonal aPL antibodies FB1 (IgG2bκ) and FD1 (IgG1κ) were obtained from NZW × BXSB F1 mice and generously provided by M. Monestier (Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA).25 Both monoclonal antibodies bind to phospholipids but do not bind to β2GPI. A monoclonal anti-mTF antibody was produced by immunizing rats with recombinant soluble mTF(1–219) expressed in a baculovirus expression system.26 1H1 antibody (rat IgG2a/kappa) inhibits murine TF activity in vitro and blocks mouse melanoma cell metastasis in vivo.26 Immunohistochemical staining of mouse frozen tissue sections with 1H1-IgG purified from ascites demonstrated specific staining in various tissues.26

Murine aPL–induced fetal loss model

Adult mice (6-8 weeks) were used in all experiments. On days 8 and 12 of pregnancy, females were treated with intraperitoneal injections of aPL-IgG (10 mg) or NH-IgG (10 mg). In some experiments, mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of mouse monoclonal antibodies FB1 (1 mg) and FD1 (1 mg) or mouse IgG isotype control (1 mg). To block TF, a group of mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of anti-mTF antibody 1H1 (0.5 mg) or an isotype-matched control antibody (rat IgG2a/κ; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) (0.5 mg) on days 6 and 10 of pregnancy. To inhibit complement activation, mice were treated with the Crry-Ig.18 Crry-Ig is a soluble chimeric protein that contains at the amino terminus the extracytoplasmic 5 short consensus repeat domains of Crry, membrane-bound complement inhibitor present in rodents, that retain classical and alternative pathway complement C3 convertase inhibitory activity followed by the hinge, CH2, and CH3 domains of the noncomplement fixing mouse IgG1 isotype. Mice were treated with intraperitoneal injections of Crry-IgG (3 mg) or murine IgG every other day from days 8 to 12.18 To deplete neutrophils, mice were treated on day 7 with rat anti–mouse granulocyte RB6–8C5 mAb (100 μg, intraperitoneally) (BD-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), or IgG2b as an isotype control as previously described.19 Neutrophil depletion was observed 24 hours after administration of anti-Gr1 and persisted through day 15.19 Mice were killed on day 15 of pregnancy, uteri were dissected, and fetal resorption frequency (FRF) was calculated (number of resorptions/total number of formed fetuses and resorptions). Resorption sites are easily identified and result from loss of a previously viable fetus. For immunohistochemistry studies, deciduas were removed from mice on day 8 of pregnancy, 2 hours after treatment with aPL-IgG. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Hospital for Special Surgery and performed in compliance with institutional guidelines.

Immunoblot analysis

Uterine contents (embryo-maternal unit) were removed from mice on day 8 of pregnancy 2 hours after the different treatments. The tissues were homogenized and lysates were resolved by electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were probed with the rat anti–mTF 1H1 antibody followed by goat antirat HRP antibody (BD-Pharmingen,6 San Diego, CA). A chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was used to visualize the bands.

Determination of TF functional activity in deciduas

Uterine contents were removed from mice on day 8 of pregnancy 2 hours after the different treatments. The tissues were homogenized and cells were lysed by repeated freeze-thaw cycles and the tissue factor was extracted with a buffer of Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane], 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Triton X-100; 12 hours at 4°C). TF procoagulant activity was assayed with one-stage clotting time using mouse plasma as described.27 TF activity was calculated by reference to a standard curve performed with mouse TF. Anti–mTF 1H1 was used to inhibit TF activity in deciduas homogenates.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

For immunohistochemistry studies, deciduas from day 8 of pregnancy were frozen in OCT compound, and cut into 10-μm sections. Sections were stained for mouse TF with 1H1 antibody and for fibrin with a polyclonal rabbit antihuman fibrinogen/fibrin antibody that cross reacts with mouse fibrin (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Neutrophils were detected using rat anti–mouse granulocyte RB6–8C5 mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and C3 with goat antimouse C3 (Cappel ICN, Aurora, OH). An HRP-labeled secondary antibody and DAB as substrate were used to develop the reaction. Peripheral blood cells were adhered to polylysine-coated slides by cytospin. Immunocytochemical staining for TF was performed using the anti–mTF 1H1 antibody followed by detection with HRP-labeled secondary antibody and DAB as substrate.

Images were acquired using a Nikon (Japan) Eclipse E400 microscope fitted with Plan Apo objective lenses (4×/0.75, 10×/0.75, 20×/0.75, and 40×/0.75), and a Nikon Digital Camera DXM 1200 and ACT-1 ver.2 for DXM 1200 image-acquisition software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Stains are given in the Figure captions.

TF expression on mouse neutrophils

To study the presence of TF on peripheral blood neutrophils, 2-color fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed. For this purpose, heparinized whole mouse blood was stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti–mouse Ly-6G (Gr-1) for FL1 (BD- Pharmingen) to identify neutrophils and biotinylated rat anti-mTF antibody 1H1 and streptavidin-PerCP (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) as the FL3 fluorochrome. Red cells were lysed with ACK buffer. Preparations were then incubated with SA-PerCP and analyzed by FACS using a FACscan (BD Biosciences).

Respiratory burst activity in neutrophils

Intracellular reactive oxygen (ROS) production was assessed with dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) by flow cytometry. This primarily nonfluorescent dye becomes fluorescent upon oxidation to rhodamine by ROS produced during the respiratory burst. DHR (10 μM) was added to heparinized whole blood, and this mixture was incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes. Red cells were lysed with ACK buffer and reactive-oxygen production was analyzed by absorbance in FL1.

Assessment of superoxide production in decidual tissue by dihydroethidium fluorescence

In situ superoxide (O2−) levels were assessed using the fluorescent probe dihydroethidium (DHE). Deciduas from day 8 of pregnancy were frozen in OCT compound, cut into 10-μm sections, and incubated with DHE (10 μM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Subsequently, the sections were washed and fluorescence images were obtained (λEx: 520, Em: 605 nm). To exclude an influence of the embedding procedure on fluorescence, samples from all treatment groups were embedded in the same block and analyzed simultaneously.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean (± standard deviation). After confirming that the data were normally distributed (Kolomogorov-Smirnov test of normalcy), the Student t test (2-tailed) was used to compare fetal resorption frequencies between groups. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was used to analyze data from FACS analysis, and TF protein and TF activity measurements. A probability of less than .05 was used to reject the null hypothesis.

Results

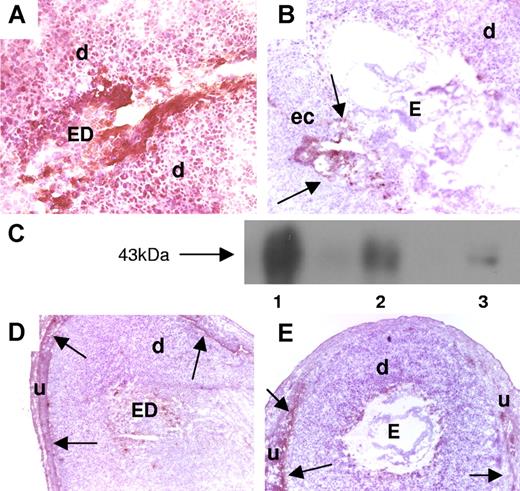

Increased TF protein expression is observed in deciduas of aPL antibody–treated mice

Mice that received aPL-IgG showed strong TF staining throughout the decidua and on embryonic debris (ED) (Figure 1A). In contrast, mice treated with NH-IgG (Figure 1B) displayed weak TF staining, which was restricted to the ectoplacental cone region and intact embryo. Western blot experiments confirmed the immunohistochemistry studies and showed increased amounts of TF in the uterine content of aPL-treated mice compared with NH-IgG–treated mice. Results from 5 experiments were analyzed by densitometry and showed a 4.5-fold (± 0.9-fold) increase in the levels of TF in the uterine content in aPL-IgG– versus NH-IgG–treated mice (P < .005) (Figure 1C).

Expression of TF in decidual tissue of aPL-treated mice. (A,B,D,E) Pregnant Balb/c mice were treated on day 8 with aPL-IgG or IgG from a nonautoimmune individual (NH-IgG) and killed 2 hours later. Uteri were dissected and decidua sections were cut. (A,B) Decidua sections stained with an anti–mouse TF antibody. The chromogen was DAB (brown) and the counterstain was hematoxylin. In aPL-treated mice (A), there was extensive TF staining (brown color) in deciduas (d) and embryo debris (ED). In contrast, the decidual tissue from NH-IgG–treated mice showed minimal staining for TF (B) at the ectoplacental cone (ec) (arrows) and intact embryo (E). Original magnification × 40. (C) TF levels in the uterine contents of aPL- and NH-IgG–treated mice were measured by Western blotting. Lane 1 shows purified mouse TF standard (3 μg); lane 2, uterine content of an aPL-treated mouse; lane 3, uterine content of a NH-IgG–treated mouse. (D,E) Immunohistochemical analysis of fibrin in sections of uteri from aPL-treated (D) and NH-IgG–treated (e) mice. Fibrin was detected only at the decidua-uterine wall interface (arrows), and no difference in the staining intensity was observed between the 2 treatments. Original magnification × 10. d indicates decidua; u, uterine wall.

Expression of TF in decidual tissue of aPL-treated mice. (A,B,D,E) Pregnant Balb/c mice were treated on day 8 with aPL-IgG or IgG from a nonautoimmune individual (NH-IgG) and killed 2 hours later. Uteri were dissected and decidua sections were cut. (A,B) Decidua sections stained with an anti–mouse TF antibody. The chromogen was DAB (brown) and the counterstain was hematoxylin. In aPL-treated mice (A), there was extensive TF staining (brown color) in deciduas (d) and embryo debris (ED). In contrast, the decidual tissue from NH-IgG–treated mice showed minimal staining for TF (B) at the ectoplacental cone (ec) (arrows) and intact embryo (E). Original magnification × 40. (C) TF levels in the uterine contents of aPL- and NH-IgG–treated mice were measured by Western blotting. Lane 1 shows purified mouse TF standard (3 μg); lane 2, uterine content of an aPL-treated mouse; lane 3, uterine content of a NH-IgG–treated mouse. (D,E) Immunohistochemical analysis of fibrin in sections of uteri from aPL-treated (D) and NH-IgG–treated (e) mice. Fibrin was detected only at the decidua-uterine wall interface (arrows), and no difference in the staining intensity was observed between the 2 treatments. Original magnification × 10. d indicates decidua; u, uterine wall.

Deciduas from aPL-treated mice showed increased TF procoagulant activity compared with deciduas from NH-IgG–treated mice (1.7 ± 0.2 vs 1.2 ± 0.3 μg TF). Surprisingly, there was no increase in fibrin staining associated with increased TF staining in deciduas from aPL-treated mice. Fibrin deposition was observed only between decidual tissue and the uterine wall, and there was no difference between aPL-treated (Figure 1D) and NH-IgG–treated (Figure 1E) mice. In addition, no thrombi were observed in deciduas from aPL-treated mice stained with phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH) histochemical stain for fibrin (data not shown). The absence of fibrin deposition and thrombi suggested that TF-dependent thrombosis does not mediate aPL-induced pregnancy loss.

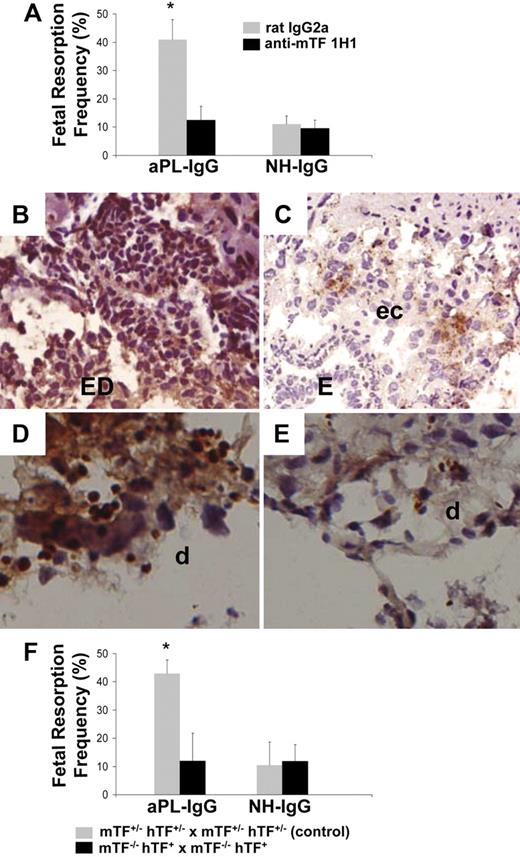

Blockade of TF prevents fetal injury in aPL-treated mice

We have shown that passive transfer of aPL-IgG causes a 43.3% (± 3.5%) frequency of fetal resorption.18,19 To assess the importance of TF in aPL-induced fetal injury, we inhibited TF with a rat monoclonal anti-mTF antibody 1H1. TF blockade prevented fetal death in aPL-treated mice (Figure 2A). The pregnancy outcomes in mice treated with both aPL-IgG and 1H1 mAb were comparable with that observed in mice receiving NH-IgG alone (Figure 2A). In deciduas from aPL-treated mice there was increased C3b deposition (Figure 2B) and neutrophil infiltration (Figure 2D) as we previously described.18,19 Blockade of TF with anti-TF mAb 1H1 diminished aPL-induced C3 deposition (Figure 2C) and neutrophil infiltration (Figure 2E). The reduction in inflammation and fetal injury by anti-mTF antibody 1H1 demonstrates that TF is a crucial effector in aPL-induced pregnancy loss.

Inhibition of TF activity protects embryos from aPL-induced inflammation and embryonic death. (A) Pregnant female mice treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG received either an anti-TF mAb (1H1) or a rat IgG2a. On day 15 of pregnancy, mice were killed, uteri were dissected, and fetal resorption rates calculated (number of resorptions/number of fetuses + number of resorptions). There were 6 to 8 mice in each group. Mice that received aPL-IgG had a high frequency of fetal resorption compared with those that received normal human IgG (P < .001). Treatment with anti-TF mAb 1H1 led to a significant reduction in the frequency of fetal resorption compared with those mice receiving aPL-IgG (P < .01). Error bars here and in panel F are SD. (B,C) Immunohistochemical analysis of C3 in sections of deciduas from mice treated with either aPL-IgG + IgG2a or aPL-IgG + anti-TF antibody. (B) In deciduas from aPL-IgG + IgG2a–treated mice, C3 deposits (brown) were present throughout decidual tissue surrounding the necrotic residual embryonic debris (ED). (C) In contrast, in mice treated with aPL-IgG plus anti-TF antibody, C3 deposition was less intense and limited to the ectoplacental cone (ec) and the embryos remained intact (E). (D,E) Immunohistochemical analysis for neutrophils in sections of deciduas from aPL-IgG and aPL-IgG + anti-TF mAb 1H1. (D) Intense staining for neutrophils (brown) was observed in deciduas from mice treated with aPL-IgG plus IgG2a. In contrast, less neutrophil infiltration was observed in deciduas from mice that had received aPL-IgG + anti-TF mAb 1H1 (E). Counterstain: hematoxylin. Original magnification × 500. (F) Pregnant mice expressing low levels of TF (mTF−/−,hTF+) were treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG. On day 15, fetal resorption rates were calculated. Approximately 40% of the embryos in control mice (mTF+/−,hTF+) treated with aPL-IgG were resorbed. Mice expressing low activity of TF showed a reduction in aPL-induced fetal resorption frequency compared with control mice (*P < .001).

Inhibition of TF activity protects embryos from aPL-induced inflammation and embryonic death. (A) Pregnant female mice treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG received either an anti-TF mAb (1H1) or a rat IgG2a. On day 15 of pregnancy, mice were killed, uteri were dissected, and fetal resorption rates calculated (number of resorptions/number of fetuses + number of resorptions). There were 6 to 8 mice in each group. Mice that received aPL-IgG had a high frequency of fetal resorption compared with those that received normal human IgG (P < .001). Treatment with anti-TF mAb 1H1 led to a significant reduction in the frequency of fetal resorption compared with those mice receiving aPL-IgG (P < .01). Error bars here and in panel F are SD. (B,C) Immunohistochemical analysis of C3 in sections of deciduas from mice treated with either aPL-IgG + IgG2a or aPL-IgG + anti-TF antibody. (B) In deciduas from aPL-IgG + IgG2a–treated mice, C3 deposits (brown) were present throughout decidual tissue surrounding the necrotic residual embryonic debris (ED). (C) In contrast, in mice treated with aPL-IgG plus anti-TF antibody, C3 deposition was less intense and limited to the ectoplacental cone (ec) and the embryos remained intact (E). (D,E) Immunohistochemical analysis for neutrophils in sections of deciduas from aPL-IgG and aPL-IgG + anti-TF mAb 1H1. (D) Intense staining for neutrophils (brown) was observed in deciduas from mice treated with aPL-IgG plus IgG2a. In contrast, less neutrophil infiltration was observed in deciduas from mice that had received aPL-IgG + anti-TF mAb 1H1 (E). Counterstain: hematoxylin. Original magnification × 500. (F) Pregnant mice expressing low levels of TF (mTF−/−,hTF+) were treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG. On day 15, fetal resorption rates were calculated. Approximately 40% of the embryos in control mice (mTF+/−,hTF+) treated with aPL-IgG were resorbed. Mice expressing low activity of TF showed a reduction in aPL-induced fetal resorption frequency compared with control mice (*P < .001).

To exclude the possibility that anti-TF altered the kinetics of aPL antibodies, we measured levels of human anticardiolipin (aCL)-reactive IgG in mice treated with 1H1 and rat IgG2a/κ. The serum t½ (4.1 hours ± 0.7 hours vs 4.5 hours ± 0.9 hours, respectively) and peak (71 GPL units ± 16 GPL units vs 65 GPL units ± 17 GPL units, respectively) levels of the aPL antibodies were indistinguishable between mice treated with 1H1 and IgG2a/κ. Similar levels of aPL antibodies were detected in deciduas from aPL+1H1 and aPL+rat IgG2a/κ by immunohistochemistry (data not shown), demonstrating that anti–TF 1H1 antibodies do not interfere with binding of aPL antibodies.

In addition, the total number of neutrophils in blood of mice treated with aPL-IgG+anti–TF 1H1 antibody, aPL-IgG, and NH-IgG was not different. Therefore, the protective effect of anti–TF 1H1 antibody is not due to neutrophil depletion caused by removal of TF-positive neutrophils opsonized by anti–TF 1H1 antibodies.

Low TF expression protects embryos from aPL-induced death

As an alternative strategy to show that TF is required for aPL-induced fetal loss, we studied pregnancy outcome in mice expressing low levels of TF.24 Low TF females were mated with low TF males (mTF−/−,hTF+ × mTF−/−,hTF+). We found thatlow TF mice treated with aPL-IgG were protected from fetal loss compared with control mice (Figure 2F). Serum t½ and peak levels of aPL antibodies were comparable in low TF mice and control mice (t½: 3.2 hours ± 0.9 hour vs 3.4 hours ± 0.6 hour, respectively; peak aCL levels: 73 GPL units ± 11 GPL units vs 81 GPL units ± 15 GPL units, respectively). These data exclude the possibility that differences in the binding of aPL antibodies to trophoblasts in the 2 strains of mice accounts for differences in aPL-IgG–mediated pathogenicity. The reduction of TF activity to less than 1% of normal levels completely rescued embryos and diminished C3 deposition and neutrophil infiltration in deciduas from aPL-treated mice to the level of mice treated with aPL-IgG and anti-TF mAb (data not shown).

Binding of aPL antibodies is insufficient to induce TF expression in decidual tissue

aPL antibodies have been shown to induce TF expression and activity on monocytes in vivo and in vitro. This occurs with F(ab)′2 fragments, suggesting that the mechanism is Fc independent.4 Indeed, some studies suggest that aPL antibodies induce a procoagulant response in endothelial cells and monocytes through interaction with toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).28,29 Given these studies and the capacity of TLR4 signaling to induce TF expression on monocytes and endothelial cells, we examined the role of TLR4 in aPL-induced pregnancy loss and increased decidual TF expression. We compared pregnancy outcomes in TLR4-sufficient (TLR4+/+) and TLR4-deficient (TLR4−/−) mice. TLR4−/− mice were not protected from aPL-induced pregnancy loss (FRF [%]: aPL-treated TLR4+/+ mice = 39% ± 9% vs 40% ± 7% in aPL-treated TLR4−/− mice) and maternal-embryo units showed TF staining of deciduas and embryo destruction comparable with aPL-treated wild-type mice (data not shown).

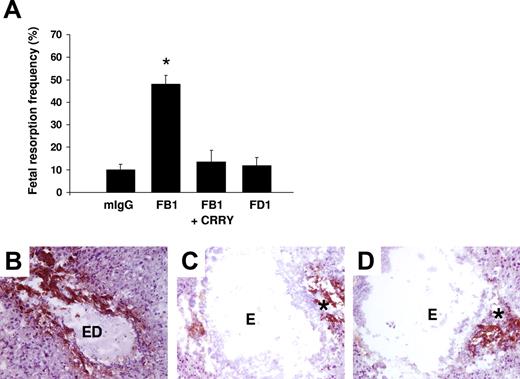

Although TLR4 is not required for fetal loss, aPL antibody binding to other surface receptors may be sufficient to cause miscarriage. To examine the possibility that direct binding of aPL antibodies induces TF expression on trophoblasts, we used 2 different mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize phospholipids on trophoblast cells, but differ in their Fc domain and thus differ in their effector potential. FB1 is an IgG2bκ that can activate complement via the classical pathway and FD1 is an IgG1κ that cannot activate complement. Both monoclonal antibodies bind to trophoblast-like BeWo cells equally but only FB1 activates complement as indicated by the presence of C3b on the trophoblast cells and the generation of the C3 cleavage product, C3a desArg, in supernatants (data not shown). We compared the effects of mouse monoclonal antibodies FB1 and FD1 in our in vivo model to determine whether aPL antibody binding alone is sufficient to induce TF and pregnancy loss. Pregnant mice treated with FB1 had a 4-fold increase in fetal resorption frequency, which could be prevented by blocking complement activation with the C3 convertase inhibitor Crry-IgG (Figure 3A). In contrast, FD1, which shows similar binding to deciduas (data not shown), did not induce miscarriages (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissue revealed an increase in TF staining only in mice treated with FB1 (Figure 3B), which was markedly decreased by inhibiting complement (Figure 3C). Minimal TF staining was present in mice treated with FD1 (Figure 3D) and this was comparable with mice treated with mouse IgG isotype control (data not shown). These results indicate that aPL antibody binding to trophoblasts is not sufficient to induce TF expressionand that complement activation is required for aPL-induced TF increase in deciduas.

Only aPL antibodies that activate complement induce an increase in TF and fetal death in pregnant mice. (A) Pregnant mice were treated on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy with 2 different mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize phospholipids on trophoblast cells. FB1 is an IgG2bκ that activates complement via classical pathway and FD1 is an IgG1κ that does not activate complement. A group of mice was treated with FB1 and the complement inhibitor Crry. On day 15, mice were killed and the frequency of fetal resorption was calculated (n = 6-7 mice/group). Mice that received FB1 had a high frequency of fetal resorption compared with those that received mIgG (P < .001). Administration of Crry protected mice from fetal death induced by FB1. Mice treated with FD1 did not show an increase in fetal resorption frequency that was observed with FB1. Error bars are SD. (B-D) Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissue from day 8 of pregnancy. Decidual tissue was processed for TF expression as described in “Materials and methods, Determination of TF functional activity in deciduas.” In FB1-treated mice (B), there was extensive TF deposition (brown) and embryo debris (ED). Treatment with Crry prevented the increase in TF expression in deciduas from FB1-treated mice (C). The decidual tissue from FD1-treated mice (D) showed minimal staining for TF in the ectoplacental cone (asterisk) and intact embryo comparable with mice treated with mIgG (not shown). Original magnification × 100.

Only aPL antibodies that activate complement induce an increase in TF and fetal death in pregnant mice. (A) Pregnant mice were treated on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy with 2 different mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize phospholipids on trophoblast cells. FB1 is an IgG2bκ that activates complement via classical pathway and FD1 is an IgG1κ that does not activate complement. A group of mice was treated with FB1 and the complement inhibitor Crry. On day 15, mice were killed and the frequency of fetal resorption was calculated (n = 6-7 mice/group). Mice that received FB1 had a high frequency of fetal resorption compared with those that received mIgG (P < .001). Administration of Crry protected mice from fetal death induced by FB1. Mice treated with FD1 did not show an increase in fetal resorption frequency that was observed with FB1. Error bars are SD. (B-D) Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissue from day 8 of pregnancy. Decidual tissue was processed for TF expression as described in “Materials and methods, Determination of TF functional activity in deciduas.” In FB1-treated mice (B), there was extensive TF deposition (brown) and embryo debris (ED). Treatment with Crry prevented the increase in TF expression in deciduas from FB1-treated mice (C). The decidual tissue from FD1-treated mice (D) showed minimal staining for TF in the ectoplacental cone (asterisk) and intact embryo comparable with mice treated with mIgG (not shown). Original magnification × 100.

Role of the complement system in TF expression and pregnancy loss in mice treated with aPL antibodies

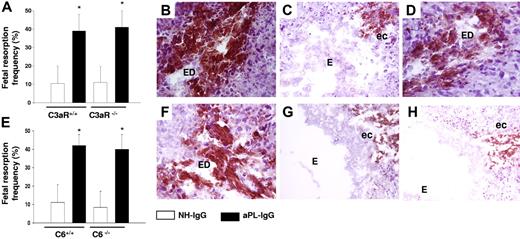

To determine the role of specific complement components in aPL-induced TF increased expression and pregnancy loss, we focused on C3, a pivotal element in the complement cascade that when cleaved leads to the generation of C3a (anaphylotoxin) and C3b (opsonin). We studied the role of C3a by performing experiments in C3aR-deficient mice (C3aR−/−). C3a was shown to induce TF expression in monocytes derived from ventricular assist device patients.30 C3aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG had fetal resorption frequencies (Figure 4A) and TF expression in deciduas (Figure 4B) comparable with those of C3aR+/+ treated with aPL-IgG, indicating that C3a-C3aR is not required for aPL-induced TF increase and pregnancy loss.

C5aR interaction and neutrophils are required for the increase in TF expression in aPL-induced fetal damage. (A) Pregnant C3aR−/− and C3aR+/+ mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions in wild-type mice (*P < .001 versus NH-IgG). C3aR−/− mice were not protected from fetal loss induced by aPL-IgG. Error bars here and in panel E are SD. (B-D,F-H) Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissue of day 8 of pregnancy. Decidual tissue was processed for TF as described in legend for Figure 1. (B) Deciduas from C3aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG showed extensive TF staining and embryo debris (ED) comparable with wild-type mice treated with aPL-IgG (not shown). (C) Deciduas from C5−/− mice showed less TF staining limited to the ectoplacental cone (ec) and intact embryos (E), while in deciduas from C5+/+ mice (D) there was extensive TF deposition and embryonic debris (ED). (E) Pregnant C6+/+ and C6−/− mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment of C6+/+ with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions (*P < .005 versus NH-IgG). C6−/− mice were not protected from fetal loss and showed an increase in TF expression induced by aPL-IgG (F). (G) Deciduas from C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG showed limited TF staining and intact embryos (E). (H) TF staining was reduced in deciduas from wild-type mice that had received anti-Gr before aPL-IgG treatment.

C5aR interaction and neutrophils are required for the increase in TF expression in aPL-induced fetal damage. (A) Pregnant C3aR−/− and C3aR+/+ mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions in wild-type mice (*P < .001 versus NH-IgG). C3aR−/− mice were not protected from fetal loss induced by aPL-IgG. Error bars here and in panel E are SD. (B-D,F-H) Immunohistochemical analysis of decidual tissue of day 8 of pregnancy. Decidual tissue was processed for TF as described in legend for Figure 1. (B) Deciduas from C3aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG showed extensive TF staining and embryo debris (ED) comparable with wild-type mice treated with aPL-IgG (not shown). (C) Deciduas from C5−/− mice showed less TF staining limited to the ectoplacental cone (ec) and intact embryos (E), while in deciduas from C5+/+ mice (D) there was extensive TF deposition and embryonic debris (ED). (E) Pregnant C6+/+ and C6−/− mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment of C6+/+ with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions (*P < .005 versus NH-IgG). C6−/− mice were not protected from fetal loss and showed an increase in TF expression induced by aPL-IgG (F). (G) Deciduas from C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG showed limited TF staining and intact embryos (E). (H) TF staining was reduced in deciduas from wild-type mice that had received anti-Gr before aPL-IgG treatment.

We have shown that C5-deficient (C5−/−) mice are protected from aPL-induced pregnancy loss.19 Therefore, we considered the possibility that C5 cleavage products might induce TF expression in deciduas. In deciduas of aPL-treated C5−/− mice, we found only weak TF staining in deciduas and the embryos were intact (Figure 4C). In contrast, C5-sufficient mice treated with aPL-IgG showed increased TF staining and injured embryos (Figure 4D). Cleavage of C5 generates 2 complement fragments: anaphylotoxin C5a and C5b, which initiates MAC (C5b-9) assembly. To identify the C5 cleavage product that induces TF expression in aPL-treated mice, we first focused on the MAC, which has been implicated in TF expression on endothelial cells and inflammatory cells.31 To investigate whether pregnancy loss is caused by MAC formation, we studied C6-deficient (C6−/−) mice. C6−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG were not protected from fetal death (Figure 4E) and showed robust TF expression in deciduas and injured embryos(Figure 4F). Pregnancy outcomes and TF staining in aPL-treated C6−/− mice were similar to those observed in C6 +/+ mice, indicating that MAC is not essential for fetal injury.

To study the role of the C5a-C5aR pathway in mediating increased TF expression, we used C5aR-deficient (C5aR−/−) mice. C5aR−/− mice were protected from aPL-induced pregnancy complications.19 Histochemical analysis of the deciduas of C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG showed no increase in TF staining and embryos remained intact (Figure 4G), indicating that C5a contributes to TF expression. Our results showed that the C5a-C5aR interaction was crucial for decidual TF increase and fetal death in aPL-treated mice. However, we were unable to detect C5aR expression on trophoblasts by FACS analysis or in mouse decidua by immunoblotting and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (data not shown). Therefore, C5a-C5aR interaction must take place on cells other than the decidual trophoblasts.

The C5a-C5aR pathway induces TF expression on neutrophils

C5a is one of the most potent inflammatory peptides. Monocytes and neutrophils, the major phagocytic leukocytes, migrate to inflammatory sites by sensing chemoattractants, such as anaphylatoxin C5a with the membrane receptor C5a receptor. The ligand-receptor interaction of these chemoattractants induces not only chemotactic movement but also the increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, the release of granular components, and the generation of radical oxygen species. Neutrophils have shown to be important mediators of fetal damage in this model of aPL-induced pregnancy loss.19 Moreover, these cells have recently been shown to express TF in response to C5a.6

To determine whether neutrophils contribute to the generation of decidual TF in aPL-induced pregnancy loss, we immunodepleted mice of neutrophils using a rat antimouse granulocyte RB6–8C5 mAb (anti-Gr1).19 Administration of aPL-IgG did not cause fetal loss or decidual TF expression in mice lacking neutrophils (Figure 4H).

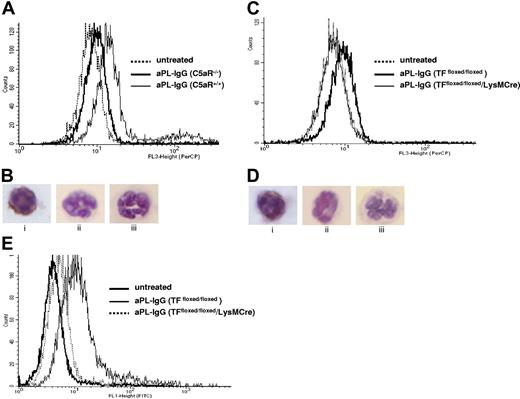

Given that neutrophils are critical mediators of fetal death and express C5aR, we tested the hypothesis that C5a induces TF expression on neutrophils in vivo. We used FACS analysis to measure TF expression on peripheral blood neutrophils from aPL-treated C5aR+/+ and C5aR−/− mice. Neutrophils from aPL-treated C5aR+/+ mice were 39% (± 16%) positive for TF (Figure 5A) compared with 9% (± 4%) of the neutrophils in C5aR−/− mice and 4% (± 2%) of the neutrophils from untreated mice (either C5aR−/− or C5aR+/+ mice). Immunocytochemical staining in neutrophils prepared on cytospin films confirmed the presence of TF on C5aR+/+ mice treated with aPL-IgG (Figure 5B) and the absence of TF in neutrophils from C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG and in neutrophils from untreated mice (Figure 5B).

TF expression on neutrophils from aPL-treated mice depends on C5aR. (A) FACS analysis of TF expression on whole blood neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of TF-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated C5aR+/+ mice in comparison with untreated mice (39% ± 16% vs 4% ± 2%, P < .005). The number of TF-positive neutrophils did not increase in aPL-treated C5aR−/− mice (9% ± 4%). (B) Immunohistochemical detection of TF on neutrophils from C5aR+/+ mice treated with aPL-IgG (i), C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG (ii), and untreated mice (iii). (C) FACS analysis of TF expression on whole blood neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of TF-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed mice in comparison with untreated mice (26% ± 9% vs 7% ± 1%, P < .001). In contrast, the number of TF-positive neutrophils did not increase in TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (6% ± 2%). (D) Immunohistochemical detection of TF on neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG (i), TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (ii), and untreated mice (iii). (E) FACS analysis of ROS production in neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of ROS-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed mice in comparison with untreated mice (29% ± 9% vs 5% ± 1%, P < .01). The number of ROS-positive neutrophils did not increase TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (10% ± 3%).

TF expression on neutrophils from aPL-treated mice depends on C5aR. (A) FACS analysis of TF expression on whole blood neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of TF-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated C5aR+/+ mice in comparison with untreated mice (39% ± 16% vs 4% ± 2%, P < .005). The number of TF-positive neutrophils did not increase in aPL-treated C5aR−/− mice (9% ± 4%). (B) Immunohistochemical detection of TF on neutrophils from C5aR+/+ mice treated with aPL-IgG (i), C5aR−/− mice treated with aPL-IgG (ii), and untreated mice (iii). (C) FACS analysis of TF expression on whole blood neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of TF-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed mice in comparison with untreated mice (26% ± 9% vs 7% ± 1%, P < .001). In contrast, the number of TF-positive neutrophils did not increase in TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (6% ± 2%). (D) Immunohistochemical detection of TF on neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG (i), TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (ii), and untreated mice (iii). (E) FACS analysis of ROS production in neutrophils from aPL-treated mice. The number of ROS-positive neutrophils increased in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed mice in comparison with untreated mice (29% ± 9% vs 5% ± 1%, P < .01). The number of ROS-positive neutrophils did not increase TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (10% ± 3%).

To investigate the role of TF in aPL-induced pregnancy loss, we performed studies using TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice. These mice have a selective deletion of the TF gene in myeloid cells. Because monocytes do not play a major role in aPL-induced pregnancy loss as shown by the lack of protection observed with monocyte depletion (data not shown) and because neutrophils express TF and are crucial effectors of fetal injury, we studied TF expression on neutrophils. FACS analysis in peripheral blood neutrophils showed that TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL have lower TF expression than neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL (TF positive cells: 7% ± 1% vs 26% ± 9%, P < .005, Figure 5C). TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice and TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with NH-IgG (control) showed low TF expression on neutrophils (TF positive cells: 6% ± 3% and 7% ± 3%, respectively). The absence of TF increase observed in neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL indicates that the LysM-Cre efficiently deletes the TF gene in neutrophils. Immunocytochemical staining in neutrophils prepared on cytospin films confirmed the presence of TF in TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG (Figure 5Di) and the absence of TF in neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL-IgG (Figure 5Dii) and in neutrophils from untreated mice (Figure 5Diii).

TF expression in neutrophils contributes to oxidative burst in aPL-treated mice

To study the effect of TF on the neutrophil oxidative burst, we measured ROS production by FACS in neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice and TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG. Thirty percent of neutrophils from aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed produced ROSs (Figure 5E), whereas significantly lower levels of ROSs were generated by neutrophils from TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice that lack TF expression (10% ± 3%). These results suggest that TF contributes to the respiratory burst in murine neutrophils, thereby potentiating neutrophil-mediated trophoblast injury in aPL-induced fetal loss.

TF expression by myeloid cells but not fetal-derived cells contributes to aPL-induced fetal loss

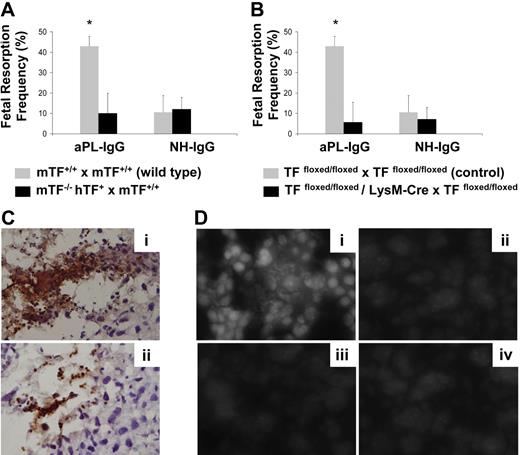

To distinguish between the contribution of maternal-derived TF versus fetal-derived cell (trophoblasts) TF in aPL-induced fetal injury, we performed studies using low TF females mated with wild-type males (mTF−/−,hTF+ × TF+/+ wild type). Low TF females mated with wild-type males were protected from aPL-induced fetal loss (Figure 6A) to a similar extent as low TF females mated with low TF males. This protection against aPL-induced fetal loss indicates the important contribution of maternal tissue factor to aPL-induced fetal injury.

TF expression by myeloid cells but not fetal-derived cells contributes to aPL-induced fetal loss. (A) Low TF female mice (mTF−/−,hTF+) mated with wild-type males (mTF+/+) and wild-type female mice mated with wild-type males (mTF+/+ × mTF+/+) were treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG. On day 15, fetal resorption rates were calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Approximately 40% of the embryos in wild-type matings treated with aPL-IgG were resorbed. Low TF female mice mated with wild-type males showed a reduction in aPL-induced fetal resorption frequency compared with wild-type mice (P < .005). Error bars here and in panel B are SD. (B) Pregnant TFfloxed/floxed and TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described19 in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions in TFfloxed/floxed mice (*P < .001 versus NH-IgG). TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice were protected from fetal loss induced by aPL-IgG. Fetal resorption frequency in these mice was comparable with TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with NH-IgG. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis for neutrophils in sections of deciduas from aPL-IgG–treated mice. Intense staining for neutrophils (brown color) was observed in deciduas from TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG (Ci). In contrast, less neutrophil infiltration was observed in deciduas from TFfloxed/floxed/LysMCre mice that had received aPL-IgG (Cii). Counterstain: hematoxylin. Original magnification × 500. (D) Superoxide (O2−) generation in decidual tissue was determined using dihydroethidium fluorescence. aPL-induced O2− formation (Di) is attenuated in TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice (Dii) and low TF mice (Diii) to a similar extent to NH-IgG–treated mice (Div). Original magnification × 800.

TF expression by myeloid cells but not fetal-derived cells contributes to aPL-induced fetal loss. (A) Low TF female mice (mTF−/−,hTF+) mated with wild-type males (mTF+/+) and wild-type female mice mated with wild-type males (mTF+/+ × mTF+/+) were treated on days 8 and 12 with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG. On day 15, fetal resorption rates were calculated as described 19in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Approximately 40% of the embryos in wild-type matings treated with aPL-IgG were resorbed. Low TF female mice mated with wild-type males showed a reduction in aPL-induced fetal resorption frequency compared with wild-type mice (P < .005). Error bars here and in panel B are SD. (B) Pregnant TFfloxed/floxed and TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice were treated with aPL-IgG or NH-IgG on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Fetal resorption frequency was calculated as described19 in “Materials and methods, Murine aPL-induced fetal loss model.” Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions in TFfloxed/floxed mice (*P < .001 versus NH-IgG). TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice were protected from fetal loss induced by aPL-IgG. Fetal resorption frequency in these mice was comparable with TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with NH-IgG. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis for neutrophils in sections of deciduas from aPL-IgG–treated mice. Intense staining for neutrophils (brown color) was observed in deciduas from TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL-IgG (Ci). In contrast, less neutrophil infiltration was observed in deciduas from TFfloxed/floxed/LysMCre mice that had received aPL-IgG (Cii). Counterstain: hematoxylin. Original magnification × 500. (D) Superoxide (O2−) generation in decidual tissue was determined using dihydroethidium fluorescence. aPL-induced O2− formation (Di) is attenuated in TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice (Dii) and low TF mice (Diii) to a similar extent to NH-IgG–treated mice (Div). Original magnification × 800.

To study the role of myeloid cell TF in aPL-induced fetal injury, we examined pregnancy outcomes in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice. aPL did not increase fetal resorption frequency in TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice (Figure 6B). In contrast, a 4-fold increase in FRF was observed in TFfloxed/floxed mice treated with aPL (Figure 6B). Thus the lack of TF expression on neutrophils completely rescued embryos from aPL-induced injury and diminished neutrophil infiltration in deciduas (Figure 6Cii). TFfloxed/floxed mice, which express TF on neutrophils, were not protected from aPL-induced pregnancy loss, and increased neutrophil infiltration was observed in decidual tissue (Figure 6Ci). Our in vitro data indicate that TF expression on neutrophils contributes to oxidative burst neutrophils, and this correlates with poor pregnancy loss outcomes in aPL-treated mice. We then explored the possibility that TF-dependent neutrophil oxidative burst induces oxidative stress in deciduas from aPL-treated mice. For this purpose, we studied superoxide production in deciduas using DHE. Sections of deciduas from aPL-treated mice exhibited increased DHE-derived fluorescence at microscopy (Figure 6Di). This increase in the amount of ethidium products was not observed in low TF mice or TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice treated with aPL (Figure 6Dii,iii). No increase in superoxide production was observed in deciduas from NH-IgG–treated mice (Figure 6Div). These results indicate there is a correlation between TF expression on neutrophils, oxidative burst, and oxidative stress injury in deciduas. TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice that do not express TF in neutrophils showed less free radical–mediated lipid peroxidation in decidual tissue and improved pregnancy outcomes than aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed mice. Taken together, our data indicate that expression of TF on neutrophils is required for aPL-induced pregnancy loss and that lack of TF expression on neutrophils prevents decidual inflammation and oxidative stress damage averting the fetal resorptions characteristic of aPL pregnancies.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that TF expression on neutrophils is an important effector molecule in fetal injury induced by aPL antibodies. We found that binding of C5a to its receptor induces TF expression in neutrophils. Importantly, TF contributes to the oxidative burst and thus enhances decidual damage that leads to pregnancy loss in APS.

Mice that received aPL-IgG showed increased TF expression throughout the decidual tissue and on embryonic debris. This higher TF expression was not associated with either fibrin deposition or thrombi formation in deciduas from aPL-treated mice. We have previously shown that anticoagulants, such as hirudin or fondaparinux, do not prevent pregnancy loss in our mouse APS model, suggesting that thrombosis is not the cause of fetal death in this model.32 These data, together with theobservation that there is no increase in fibrin deposition or detectable thrombi in deciduas from aPL-treated mice, support the idea that TF promotes fetal loss not by inducing thrombus formation but by enhancing inflammation. Our results are consistent with previous reports that demonstrate TF enhances inflammation in a model of crescentic glomerulonephritis in a fibrin-independent manner.17 In addition, the death of embryos lacking the anticoagulant protein thrombomodulin is associated with increased TF expression without fibrin deposition or thrombosis. The death of the embryos appears to be due to growth arrest of trophoblast cells.33 These studies indicate that TF increases inflammation in different models.

We demonstrated that blockade of TF or reducing TF expression has protective effect in aPL-induced pregnancy loss. Reduced levels of TF not only rescue pregnancies in aPL-treated mice but also diminish inflammation. Less decidual inflammation (fewer neutrophils and less C3 deposition) and increased embryo survival are observed in aPL-treated low TF–expressing mice and mice that were treated with aPL plus anti-TF Ab. These observations suggest that TF is a proinflammatory molecule in aPL-induced pregnancy loss. Blockade of TF has been shown to limit inflammation and tissue injury in other in vivo studies. Anti-TF antibody attenuated septic shock,34 and antisense TF mRNA suppressed leukocyte adhesion and coagulation-dependent inflammation in renal and hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury.35 Furthermore, low TF mice are protected from endotoxemia and renal failure and neutrophil accumulation and show lower levels of chemokines after ischemia reperfusion.36,37

We previously demonstrated that complement activation is an essential intermediate in aPL-induced pregnancy loss.19,20 Here, we found that aPL-induced TF expression depends on complement activation. Antibodies that bind to trophoblasts but do not activate the complement system (FD1) neither induce TF increase nor induce fetal damage, suggesting that direct binding of aPL is not enough to modulate TF expression and cause fetal demise. Only aPL antibodies that cause complement activation (FB1) induce TF expression and fetal death. Moreover, complement inhibition with Crry-Ig prevented aPL-induced TF increase and fetal injury in this model. We identified the complement components that are required to induce TF expression. Poor pregnancy and increased decidual TF expression were observed in C3aR- and C6-deficient mice, indicating that neither C3a nor the MAC is required for fetal damage. On the other hand, C5aR-deficient mice were protected from pregnancy loss and no increased TF expression was observed in the deciduas of these mice, indicating that the proinflammatory sequelae of C5a-C5aR is critical for TF expression and fetal death induced by aPL antibodies.

C5a is an anaphylotoxin that recruits and activates neutrophils. We have previously shown that neutrophils are required for aPL-induced pregnancy loss. In mice depleted of neutrophils, administration of aPL did not cause fetal loss. Similarly, induction of TF expression was prevented by neutrophil depletion. These data indicate that induction of TF expression is downstream of complement activation and neutrophil recruitment. We demonstrated by flow cytometry that neutrophils from aPL-treated mice express TF and that this process is dependent on C5a-C5aR interaction. These results are consistent with the reported studies by Ritis et al, who recently demonstrated by in vitro experiments that aPL-induced complement activation and downstream signaling via C5a receptors in human neutrophils lead to the induction of TF expression in neutrophils.6

We have shown that neutrophils play a key role in aPL antibody–induced fetal loss. In contrast, monocytes do not contribute to fetal loss. Experiments performed using low TF females mated with wild-type males and TFfloxed/floxed/LysMCre mice allowed us to distinguish the role of trophoblasts TF from that of myeloid cells TF. The protection from aPL-induced pregnancy loss observed in both of these mice emphasizes the crucial role of TF in maternal neutrophils. Experiments performed using TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice that do not express TF on neutrophils confirmed that the neutrophil is the pathologic site of TF expression in aPL-induced fetal injury. TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice were protected from aPL-induced fetal damage. Normal pregnancies and diminished decidual TF expression and inflammation were observed in aPL-treated TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice, suggesting that TF expression on neutrophils modulates the ability of neutrophils to induce tissue damage.

Importantly, we demonstrate that TF expression on neutrophils contributes to the production of ROSs, potent effector molecules of inflammatory fetal injury. We showed that TF expression on neutrophils is required for oxidative burst induced in response to aPL antibodies. This is consistent with the enhanced oxidative stress found in deciduas from aPL-treated mice. In aPL-treated mice, increased superoxide production in decidual tissue and fetal demise were observed. TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice that do not express TF on neutrophils in response to aPL did not show oxidative stress in deciduas and pregnancies were protected. In addition, low TF mice treated with aPL did not show signs of oxidative stress in the deciduas and embryo survival. Enhancement of ROS production by TF was also found in human macrophages in vitro and in vivo in rabbit peritoneal macrophages.38 It has been described that binding of TF to factor VIIa results in proinflammatory changes in human macrophages in vitro and that anti-TF antibodies attenuated ROS production in rabbit peritoneal macrophages in vivo.39 Binding of FVIIa to TF enhances LPS induction of proinflammatory genes expression in monocyte-derived macrophages.39 This amplification loop of leukocyte activation and recruitment may also account for the proinflammatory effects of TF observed in aPL-induced fetal injury. In addition, TF has been shown to enhance cell survival of baby hamster kidney cells.40 Another study showed that C5a delayed neutrophil apoptosis and enhanced organ injury in a rat model of sepsis.41 This is another possible mechanism by which aPL-induced TF expression in neutrophils may enhance neutrophil survival and exacerbate fetal injury.

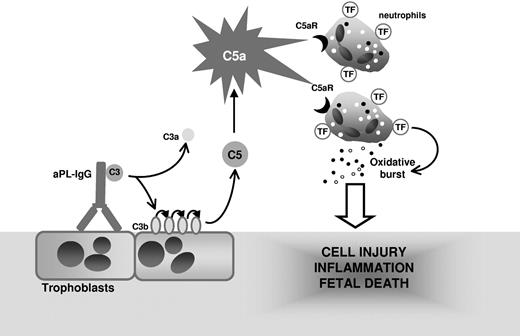

Collectively, our study demonstrates that TF expression on neutrophils is essential in the pathogenesis of aPL-induced fetal loss and reveals a functional linkage among C5a, neutrophil activation, and fetal injury. We propose that complement activation is initiated by aPL-IgG binding to trophoblasts and leads to generation of the anaphylatoxin C5a, which attracts and activates neutrophils through C5aR (Figure 7). The engagement of the neutrophil C5a-C5aR pathway results in neutrophil TF expression. TF expression enhances neutrophil oxidative burst leading to decidual injury and fetal death. Although we have used a mouse model, we believe that the finding that neutrophil TF is an important effector in aPL-induced inflammation may allow the development of new therapies to abrogate theinflammatory loop caused by TF and improve pregnancy outcomes in patients with APS.

Mechanism of aPL-induced TF increase and fetal death. APL antibodies are preferentially targeted to the placenta where they activate complement leading to the generation of potent anaphylatoxin C5a. C5a attracts and activates neutrophils. As a result of C5a-C5aR interaction, neutrophils express TF. TF on neutrophils contribute to oxidative burst and subsequent trophoblast injury and ultimately fetal death.

Mechanism of aPL-induced TF increase and fetal death. APL antibodies are preferentially targeted to the placenta where they activate complement leading to the generation of potent anaphylatoxin C5a. C5a attracts and activates neutrophils. As a result of C5a-C5aR interaction, neutrophils express TF. TF on neutrophils contribute to oxidative burst and subsequent trophoblast injury and ultimately fetal death.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Mary Kirkland Center for Lupus Research at Hospital for Special Surgery (G.G.), S.L.E. Foundation (G.G.), and the National Institutes of Health (N.M.).

We thank Dr B. Paul Morgan (School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom) for making C6-deficient mice available for our studies, Dr Craig Gerard (Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for generously providing the C3aR- and C5aR-deficient mice, and Dr Marc Monestier (Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA) for generously providing the mouse monoclonal anticardiolipin antibodies.

Authorship

Contribution: P.R. conducted experiments; M.T. and R.T. made and characterized TFfloxed/floxed mice and bred these mice with LysM-Cre mice; J.E.S. contributed to paper editing; D.K. provided rat antimouse TF 1H1 antibodies and designed 1H1 treatment experiments; N.M. provided the low TF mice and TFfloxed/floxed/LysM-Cre mice, and contributed to the experimental design, discussions, and writing of the paper; G.G. conceptually designed, executed, and interpreted experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.R., M.T., R.T., J.S., N.M., and G.G. declare no competing financial interests. D.K. is an employee of Genentech and declares no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Guillermina Girardi, Hospital for Special Surgery, 535 E 70th St, New York, NY 10021; e-mail:girardig@hss.edu.