Abstract

We analyzed the outcome of 692 patients with severe aplastic anemia (SAA) receiving transplants from HLA-matched siblings. A total of 134 grafts were peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) grafts, and 558 were bone marrow (BM) grafts. Rates of hematopoietic recovery and grades 2 to 4 chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were similar after PBPC and BM transplantations regardless of age at transplantation. In patients older than 20 years, chronic GVHD and overall mortality rates were similar after PBPC and BM transplantations. In patients younger than 20 years, rates of chronic GVHD (relative risk [RR] 2.82; P = .002) and overall mortality (RR 2.04; P = .024) were higher after transplantation of PBPCs than after transplantation of BM. In younger patients, the 5-year probabilities of overall survival were 73% and 85% after PBPC and BM transplantations, respectively. Corresponding probabilities for older patients were 52% and 64%. These data indicate that BM grafts are preferred to PBPC grafts in young patients undergoing HLA-matched sibling donor transplantation for SAA.

Introduction

Transplantation of bone marrow (BM) from an HLA-matched sibling donor is an effective treatment for severe aplastic anemia (SAA) with long-term survival in excess of 80% and graft failure rates of approximately 10%.1–7 Unpublished data (January 2007) from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) suggest approximately 60% of HLA-matched sibling donor transplantations for SAA now use peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) grafts. A similar switch to PBPC over BM grafts is reported in leukemia transplantations.8–10 The higher rate of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) may be offset by lower relapse rates in some settings. In contrast, there is no perceived benefit of chronic GVHD for SAA. Further, few data on PBPCs for SAA are reported.11–15 In a preliminary analysis from our group, PBPC grafts appeared to contribute to higher mortality.16 Here, we report chronic GVHD and long-term overall survival rates in 134 PBPC recipients and 558 BM recipients of HLA-matched sibling donor transplants for SAA.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Data on patients undergoing their first PBPC and BM HLA-matched sibling transplantation from 1995 to 2003 were obtained from the EBMT and the Statistical Center of the CIBMTR at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Only patients who received transplants at centers that provided a minimum of 12 months of follow-up on all their surviving patients were included. The Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin approved this study. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical methods

The probabilities of hematopoietic recovery (neutrophil count ≥ 0.5 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days and platelet count ≥ 20 × 109/L for 7 days, unsupported) and acute and chronic GVHD were calculated using the cumulative incidence function method in which death without the event was the competing event.17 The probability of overall survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, death from any cause was considered an event, and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up.17 The 95% confidence interval (CI) is calculated using log transformation. Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed using a stepwise forward selection, with a P value of .05 or less to indicate statistical significance.18 Variables considered in regression models are shown in Table 1. Results are expressed as relative risk (RR); that is, the relative occurrence of the event with transplantation of BM compared with that of PBPCs. P values are 2-sided. SAS software version 9.1 was used for analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Patient, disease, and transplantation characteristics by recipient age at transplantation

| Variable . | Aged 20 y or younger* . | Older than 20 y† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow . | Peripheral blood . | Bone marrow . | Peripheral blood . | |

| No. | 305 | 44 | 253 | 90 |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 185 (61) | 24 (55) | 148 (59) | 44 (49) |

| Performance score, no. (%) | ||||

| 90-100 | 180 (59) | 25 (57) | 110 (43) | 32 (36) |

| Lower than 90 | 81 (27) | 13 (30) | 94 (37) | 43 (48) |

| Unknown | 44 (14) | 6 (14) | 49 (19) | 15 (17) |

| Interval, diagnosis to HCT, no. (%) | ||||

| ≤ 6 mo | 248 (81) | 33 (75) | 167 (66) | 46 (51) |

| Longer than 6 mo | 57 (19) | 11 (25) | 86 (34) | 44 (49) |

| Years of transplantation, no. (%) | ||||

| 1995-1999 | 201 (66) | 18 (41) | 175 (69) | 33 (36) |

| 2000-2003 | 104 (34) | 26 (59) | 78 (31) | 57 (64) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | ||||

| TBI + other | 19 (6) | 2 (5) | 12 (5) | 7 (8) |

| Cy + TLI/TAI ± ATG | 11 (4) | 2 (5) | 22 (9) | 6 (7) |

| Cy + ATG | 193 (63) | 21 (48) | 118 (47) | 44 (49) |

| Cy | 62 (20) | 13 (30) | 67 (26) | 11 (12) |

| Bu + Cy ± other | 16 (5) | — | 22 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Fludarabine + other | 2 (1) | 6 (14) | 9 (4) | 16 (18) |

| Cy + thiotepa | — | — | 2 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | — | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | ||||

| None | 1 (<1) | — | 2 (1) | — |

| CSA ± other | 38 (13) | 12 (27) | 33 (13) | 24 (27) |

| CSA + MTX ± other | 255 (84) | 28 (64) | 214 (85) | 51 (57) |

| Tacrolimus ± other | 2 (1) | — | 1 (<1) | 6 (7) |

| Other | — | 2 (5) | ||

| Unknown | 9 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (1) | 9 (10) |

| Donor-recipient sex match, no. (%) | ||||

| Male to male | 90 (30) | 9 (20) | 93 (37) | 20 (22) |

| Male to female | 66 (22) | 9 (20) | 63 (25) | 28 (31) |

| Female to male | 95 (31) | 14 (32) | 55 (22) | 24 (27) |

| Female to female | 54 (18) | 12 (27) | 41 (16) | 18 (20) |

| Unknown | — | — | 1 (<1) | — |

| Follow-up of survivors, median (range), mo | 68 (16-131) | 50 (22-105) | 68 (13-134) | 41 (15-102) |

| Variable . | Aged 20 y or younger* . | Older than 20 y† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow . | Peripheral blood . | Bone marrow . | Peripheral blood . | |

| No. | 305 | 44 | 253 | 90 |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 185 (61) | 24 (55) | 148 (59) | 44 (49) |

| Performance score, no. (%) | ||||

| 90-100 | 180 (59) | 25 (57) | 110 (43) | 32 (36) |

| Lower than 90 | 81 (27) | 13 (30) | 94 (37) | 43 (48) |

| Unknown | 44 (14) | 6 (14) | 49 (19) | 15 (17) |

| Interval, diagnosis to HCT, no. (%) | ||||

| ≤ 6 mo | 248 (81) | 33 (75) | 167 (66) | 46 (51) |

| Longer than 6 mo | 57 (19) | 11 (25) | 86 (34) | 44 (49) |

| Years of transplantation, no. (%) | ||||

| 1995-1999 | 201 (66) | 18 (41) | 175 (69) | 33 (36) |

| 2000-2003 | 104 (34) | 26 (59) | 78 (31) | 57 (64) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | ||||

| TBI + other | 19 (6) | 2 (5) | 12 (5) | 7 (8) |

| Cy + TLI/TAI ± ATG | 11 (4) | 2 (5) | 22 (9) | 6 (7) |

| Cy + ATG | 193 (63) | 21 (48) | 118 (47) | 44 (49) |

| Cy | 62 (20) | 13 (30) | 67 (26) | 11 (12) |

| Bu + Cy ± other | 16 (5) | — | 22 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Fludarabine + other | 2 (1) | 6 (14) | 9 (4) | 16 (18) |

| Cy + thiotepa | — | — | 2 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | — | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, no. (%) | ||||

| None | 1 (<1) | — | 2 (1) | — |

| CSA ± other | 38 (13) | 12 (27) | 33 (13) | 24 (27) |

| CSA + MTX ± other | 255 (84) | 28 (64) | 214 (85) | 51 (57) |

| Tacrolimus ± other | 2 (1) | — | 1 (<1) | 6 (7) |

| Other | — | 2 (5) | ||

| Unknown | 9 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (1) | 9 (10) |

| Donor-recipient sex match, no. (%) | ||||

| Male to male | 90 (30) | 9 (20) | 93 (37) | 20 (22) |

| Male to female | 66 (22) | 9 (20) | 63 (25) | 28 (31) |

| Female to male | 95 (31) | 14 (32) | 55 (22) | 24 (27) |

| Female to female | 54 (18) | 12 (27) | 41 (16) | 18 (20) |

| Unknown | — | — | 1 (<1) | — |

| Follow-up of survivors, median (range), mo | 68 (16-131) | 50 (22-105) | 68 (13-134) | 41 (15-102) |

A total of 155 transplantation centers contributed data for this study. Of these, 91 transplantation centers contributed data on BM transplantations only, 27 centers contributed data on PBPC transplantations only, and 37 centers contributed data on both BM and PBPC transplantations. Most transplantation centers (121 [78%] of 155) contributed 5 or fewer patients, 22 (14%) centers contributed 6 to 10 patients, and only 12 (7%) centers contributed more than 10 patients. The median number of patients per center is 3.

HCT indicates hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; TBI, total body irradiation; TLI, total lymphoid irradiation; TAI, total abdominal irradiation; Cy, cyclophosphamide; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; Bu, busulfan; CSA, cyclosporine; and MTX, methotrexate; — indicates not applicable.

A total of 107 centers performed transplantations on patients 20 years old and younger. A total of 91 (85%) centers performed transplantations on 5 or fewer patients, 13 (12%) centers performed transplantations on 6 to 10 patients, and 2 (3%) centers performed transplantations on more than 10 patients. The median number of patients who received transplants per center is 2.

A total of 109 centers performed transplantations on patients older than 20 years. A total of 94 (86%) centers performed transplantations on 5 or fewer patients, 9 (8%) centers performed transplantations on 6 to 10 patients, and 6 (6%) centers performed transplantations on more than 10 patients. The median number of patients who received transplants per center is 2.

Results and discussion

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Characteristics of the treatment groups were similar except that PBPC transplantations were more recent, and the median time from diagnosis to transplantation was longer in PBPC recipients older than 20 years compared with BM recipients of similar age (6 months vs 4 months; P = .003). In patients 20 years old and younger, the corresponding time was 2 months for both treatment groups. More than half (59%) of PBPC transplantations in patients 20 years old and younger occurred between 2000 and 2003, compared with 34% of BM transplantations (P = .001). Similarly, 64% of PBPC transplantations in patients older than 20 years occurred between 2000 and 2003, compared with 31% of BM transplantations (P < .001). Cyclophosphamide with or without antithymocyte globulin was the predominant conditioning regimen, and all received T-replete grafts.

Hematopoietic recovery

Though the median time to neutrophil (13 days vs 18 days) and platelet recovery (19 days vs 25 days) were faster after transplantation of PBPCs compared with BM, the probabilities of neutrophil recovery at day 28 (89% vs 85%) and platelet recovery at day 100 (80% vs 85%) were similar. The proportion of patients with primary graft failure (9% vs 9%) and secondary graft failure (6% vs 7%) were similar after transplantation of PBPCs and BM, respectively.

GVHD

Rates of grades 2 to 4 acute GVHD were similar after PBPC and BM transplantations (RR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.59-3.39; P = .436; and RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.60-1.79; P = .909) in patients 20 years old and younger and older than 20 years, respectively. The day-100 probabilities of acute grades 2 to 4 GVHD in younger patients were 10% and 14%, after BM and PBPC transplantations, respectively. Corresponding probabilities in older patients were 20% and 19%.

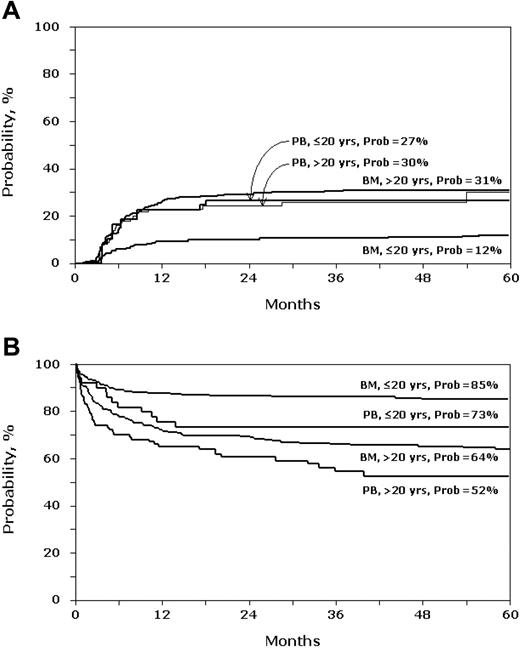

Chronic GVHD rates were higher after PBPC transplantations than after BM transplantations in patients 20 years old and younger (RR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.46-5.44; P = .002; Figure 1A). In those older than 20 years, rates were similar after PBPC and BM transplantations (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.71-1.85; P = .589). This differs from some reports where chronic GVHD rates were higher with PBPC grafts regardless of age.19–21 Notably, the significant difference in chronic GVHD rate after PBPC and BM transplantations was most evident with follow-ups of more than 6 to 7 years. It remains to be seen whether, with longer follow-up, chronic GVHD rates will be higher in older patients.

Patients 20 years old and younger and older than 20 years with SAA after PBPC (PB) and BM transplantation. (A) Probability of chronic graft-versus-host disease. (B) Probability of overall survival.

Patients 20 years old and younger and older than 20 years with SAA after PBPC (PB) and BM transplantation. (A) Probability of chronic graft-versus-host disease. (B) Probability of overall survival.

Overall mortality

Overall mortality rates were higher after PBPC transplantations than after BM transplantations in patients 20 years old and younger (RR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.09-3.78; P = .024; Figure 1B). In patients older than 20 years, rates were similar after PBPC and BM transplantations (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.87-1.85; P = .119). Other factors affecting mortality rates after PBPC and BM transplantations were poor performance score (< 90) and time from diagnosis to transplantation. For patients aged 20 years and younger, there was a 2-fold increase in mortality in those with poor performance scores (RR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.16-3.44; P = .012) and a 3-fold increase in mortality when transplantation occurred more than 6 months after diagnosis (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.93-5.40; P < .001). Similarly, in patients older than 20 years, rates were higher in those with poor performance scores (RR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.57-3.44; P < .001) and when transplantation occurred more than 6 months after diagnosis (RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.01-2.05; P = .041).

Higher chronic GVHD after PBPC transplantations in younger patients likely contributed to the excess mortality. This has been reported in younger patients with acute leukemia and older patients with good-risk chronic myeloid leukemia.20,21 Others have reported the significant negative impact of chronic GVHD on survival after HLA-matched sibling transplantations.5 Though we did not observe a statistically significant survival advantage for 1 graft type over the other in patients older than 20 years of age, the 5-year probability of overall survival after PBPC transplantations was 52% compared with 64% after BM transplantations. The recent report by Locasciulli and colleagues7 demonstrate improvement in overall survival with BM grafts over time, suggesting the recent use of PBPC grafts from HLA-matched sibling donors for SAA have for the first time in more than a decade resulted in lower survival rates.

Ours is not a randomized study, and is subject to selection bias as well as other known and unknown or unmeasured factors that may have influenced the choice of 1 graft over another. However, known patient-, disease-, and transplant-related characteristics were comparable between PBPC and BM groups. Further, 59% of centers used BM grafts and 17% used PBPC grafts exclusively, and 24% used both BM and PBPC grafts. At centers that used both grafts, PBPCs were used more frequently after 2000 and accounted for 50% of transplantations compared with 20% of BM transplantations, independent of age. These data indicate PBPC grafts from HLA-matched siblings were associated with higher chronic GVHD and lower survival in younger patients. The lower—though not statistically significant—overall survival rates after PBPC transplantations in older patients is discouraging. New transplantation technologies have brought about constant improvement in outcome for the last 20 years, and for the first time, such a change has resulted in lower survival.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant U24-CA76518-08 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: H.S., J.R.P., J.C.W.M., and M.E. had primary responsibility for the project and contributed equally to study design, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, and approval of final manuscript. R.O. prepared the data file. J.P.K. and M.E. performed the statistical analysis. A.B., B.M.C., R.E.C., R.P.G., J.P.K., A.V.M.B.S., and G.S. participated in data interpretation, manuscript preparation, and approval of final manuscript. C.N.B., E.B., M.F., A.L., and R.O. approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary Eapen, Statistical Center, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, Medical College of Wisconsin, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: meapen@mcw.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal