Abstract

The CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) α transcription factor is indispensable for myeloid differentiation. In various myeloid leukemias, C/EBPα is mutated or functionally impaired due to decreased C/EBPα expression or phosphorylation. In order to investigate the functional consequences of decreased C/EBPα function in AML, we reintroduced C/EBPα in primary CD34+ sorted acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells using a lentiviral approach. Self-renewal and differentiation of primary AML stem cells were studied on long-term MS5 cocultures. Activation of C/EBPα immediately led to a growth arrest in all AML cultures (N = 7), resulting in severely reduced expansion compared with control cultures. This growth arrest corresponded with enhanced myeloid differentiation as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis for CD14, CD15, and CD11b. Myeloid differentiation was further confirmed by the up-regulation of neutrophil elastase and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) receptor in C/EBPα transduced cells. C/EBPα-expressing AML CD34+ cells failed to generate second and third leukemic cobblestone areas (L-CAs) in serial replating experiments, while control cultures could be sequentially passaged for more than 4 times, indicating that reintroduction of C/EBPα impaired the self-renewal capacity of the leukemic CD34+ compartment. Together, our data indicate that low C/EBPα levels are necessary to maintain self-renewal and the immature character of AML stem cells.

Introduction

The transcription factor C/EBPα is a major determinant of myeloid differentiation. Its expression is low in stem cells and uncommitted progenitors and is up-regulated when common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) develop.1,2 Concomitantly, the expression is reduced upon differentiation toward the megakaryocytic-erythroid lineage and is abolished in lymphoid cells.2 Overexpression in cells with GMP potential indicated that C/EBPα induces granulocytic differentiation and blocks the monocytic differentiation program.1 This is in line with the granulocytopenia in C/EBPα−/− mice, without affecting other lineages.3 Although initial studies have not shown effects on monocyte/macrophage development, conditional knockout mice for C/EBPα have indicated that this development is indeed affected as well.4 Recently, overexpression studies have shown that C/EBPα can also direct monocytic development,5 which is consistent with data demonstrating a requirement for C/EBPα in the transition from CMPs to GMPs,6 but not for development toward mature cells.

C/EBPα has been implicated in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal. The repopulating ability of C/EBPα−/− HSCs is increased compared with wild-type (wt) HSCs.6 These mice demonstrate an accumulation of immature myeloid blasts in the bone marrow upon transplantation with C/EBPα−/− HSCs.6 The block in myeloid differentiation, combined with an enhanced self-renewal, closely resembles some characteristics of leukemic development. Indeed, C/EBPα has been suggested to be a common denominator in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML).7 In the last few years, various mechanisms have been reported through which C/EBPα is negatively regulated in various AML subtypes. Mutations in the N-terminus have been described in patients with a FAB M1 and M2 subtype without AML-ETO translocation.8–10 These N-terminal mutations give rise to a truncated dominant-negative form of C/EBPα, which interferes with DNA binding and transactivation of the wt C/EBPα.8 C-terminal mutations of C/EBPα have been described in FAB subtypes M1, M2, and occasionally M4, and result in deficiency in DNA binding of C/EBPα.11,12 AMLs with an AML-ETO translocation have been demonstrated to down-regulate C/EBPα at the transcriptional level,9 although some studies have also shown that AML-ETO can associate with and inhibit C/EBPα function.13 In AML patients with Flt3-ITD mutations or inv16, suppression of C/EBPα expression was demonstrated,14,15 whereas functional inhibition of C/EBPα through Flt3-ITD–induced phosphorylation has also been reported.16 Promoter hypermethylation might also reduce C/EBPα expression in at least some AMLs,17 and, last, the fusion gene AML1-MDS1-EVI1 has been demonstrated to suppress DNA binding of C/EBPα.18 Together, all these mechanisms lead to decreased functionality of C/EBPα in terms of DNA binding and expression of target genes, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) receptor, macrophage-CSF (M-CSF) receptor, and IL-6 receptor.3,4,19 This block at the CMP stage in the differentiation program, combined with the enhanced self-renewal potential, may subsequently contribute to leukemic transformation.

In overexpression studies of C/EBPα in the leukemic AML-ETO-expressing Kasumi cell line and in Flt3-ITD–expressing 32D and MV4;11 cell lines have demonstrated that impaired myeloid differentiation could be rescued.9,14,16 Recently, we demonstrated that the STAT5-induced erythroid differentiation and the subsequent block in myeloid differentiation of human cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells involves down-modulation of C/EBPα,20 which could be counterbalanced by reintroduction of C/EBPα.21 In studies in which patients with AML were treated with the Flt3 inhibitor CEP-701, re-expression of C/EBPα was observed after 4 weeks of treatment, and this was correlated with an enhanced expression of surface markers CD11b and CD15.14 However, a direct relation between these 2 events has not yet been established in primary AML samples. This prompted us to reintroduce C/EBPα into AML blasts. For these studies, we used the CD34+-sorted subfraction from the blast cell population. This cell fraction contains the AML long-term culture-initiating cell (AML-LTC-IC)22 activity and might be most informative regarding the cellular functions of C/EBPα in long-term leukemic stem cell cultures. The results demonstrate that reintroduction of C/EBPα in primary CD34+-sorted AML cells leads to a rapid growth arrest, with an associated increased expression of differentiation markers. This enhanced differentiation is accompanied by a loss of self-renewal, as assessed by serial replating of leukemic stem cells. We thus conclude that down-regulation of C/EBPα function in primary human AMLs is necessary for maintenance of the leukemic phenotype by keeping them undifferentiated and upholding their self-renewal.

Materials and methods

Long-term cultures on stroma

AML blasts from peripheral blood or bone marrow from untreated patients with AML were studied after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. AML mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and CD34+ cells were selected by MiniMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Utrecht, The Netherlands) or sorted on a MoFlo (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA). After transduction, 200 000 cells were plated onto T25 flasks preplated with MS5 stromal cells and expanded in long-term culture (LTC) medium (αMEM supplemented with heat-inactivated 12.5% FCS, heat-inactivated 12.5% horse serum [Sigma, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands], penicillin and streptomycin, 200 mM glutamine, 57.2 μM β-mercaptoethanol [Sigma], and 1 μM hydrocortisone [Sigma]) supplemented with 20 ng/mL IL-3 (Gist-Brocades, Delft, the Netherlands), G-CSF (Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Amstelveen, the Netherlands), and thrombopoietin (TPO; Kirin, Tokyo, Japan). Cultures were kept in the presence or absence of 500 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Half of the cultures were harvested weekly for analysis. CB CD34+ cells were derived from neonatal cord blood from healthy full-term pregnancies after informed consent from the Obstetrics departments of the Martini Hospital and University Medical Center in Groningen, the Netherlands, and isolated by MiniMACS selection.

Flow cytometry analysis

All fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses were performed on a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson [BD], Alpen a/d Rijn, the Netherlands), and data were analyzed using WinList 3D (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME). Cells were sorted on a MoFlo. Antibodies were obtained from BD.

Lentiviral transductions

A total of 2.5 × 106 293T human embryonic kidney cells were transduced with 3 μg pCMV Δ8.91, 0.7 μg VSV-G, and 3 μg pRRL-Venus or pRRL-C/EBPα-ER (pRRL-Venus is a kind gift from Dr C. Baum, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany). pRRL-C/EBPα-ER was cloned by swapping the EcoRI fragment from C/EBPα-ER from MiNR1-C/EBPα-ER (described previously)21 blunt into the SnaB1 site of pRRL-Venus. After 24 hours, medium was changed to hematopoietic progenitor growth medium (HPGM; Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium), and after 12 hours, supernatant containing lentiviral particles was harvested and stored at −80°C. CD34+ AML blasts and CB CD34+ cells were isolated with MiniMACS columns and subsequently cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, IL-3, G-CSF, and TPO (20 ng/mL each) for 4 hours or in HPGM supplemented with c-Kit ligand), Flt-3 ligand (both from Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and TPO (100 ng/mL each) for 16 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2, respectively. AML blasts were transduced in 3 consecutive rounds of 8 to 12 hours with lentiviral supernatant supplemented with 10% FCS, IL-3, G-CSF, and TPO (20 ng/mL), polybrene (4 μg/mL; Sigma), and CB CD34+ cells in 2 consecutive rounds of 8 to 12 hours with lentiviral supernatant supplemented with c-Kit ligand/Flt-3 ligand/TPO (100 ng/mL each) and polybrene (4 μg/mL). Transduction efficiency was measured by FACS analysis and overexpression was investigated by means of Western blot using antibodies against C/EBPα (N19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and green fluorescent protein (GFP, which recognizes Venus as well; Invitrogen, Breda, the Netherlands) in a 1:1000 dilution in PBS on an Odyssey infrared scanner (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) or using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Almere, the Netherlands).

Q-PCR

Target gene expression was investigated by means of quantitative reverse transcription (RT)–polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR); sequences and conditions are available on request. For RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from 1 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells using the RNeasy kit from Qiagen (Venlo, the Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RNA was reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (Roche Diagnostics). For PCR, 2 μL cDNA was amplified (sequences and conditions are available on request) in a total volume of 25 μL using 2 U Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics). As a negative control, RNA minus reverse transcriptase (−RT) prepared cDNA was used in PCR reactions. Aliquots of 10 μL were run on 1.5% agarose gels. For real-time RT-PCR, 2 μL aliquots of cDNA were real-time amplified using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, the Netherlands) on a MyIQ thermocycler (Bio-Rad) and quantified using MyIQ software (Bio-Rad). GAPDH expression was used to calculate and normalize expression of all genes investigated.

EMSAs

Nuclear extracts of 25 000 sorted CD34+ (transduced) AML cells that were prestimulated with 20 ng/ml G-CSF for 1 hour were prepared according to the mini-extracts method.23 Electrophorectic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis was performed by incubating 5 μL nuclear extract with 5′-IRDye (Biolegio, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) 700–labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides for 30 minutes at room temperature. For the C/EBPα-specific probe, the sequence of the C/EBPα binding site in the promoter of the G-CSF receptor (G-CSF-R) was used (5′-tcgaggtgttgcaatccccag-3′), and for the NF-κB–specific probe, the sequence of the NF-κB binding site in the EGP-2 promoter was used (5′-ggtccggggaccccctcg-3′) [italics indicate the nucleotides to which the transcription factors bind]. Binding reactions were run on nondenaturing 4% acrylamide gels in 1 × TBE, and the gels were scanned using an Odyssey infrared scanner (Li-Cor Biosciences). To check for specificity of the reactions, 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide was added to the binding reactions. For supershift analysis, 1 μL C/EBPα-specific antibody (SC-61; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or 1 μL GATA1-specific antibody (SC-266; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added simultaneously with the probe.

Microscopy and cytospins

For morphologic analysis, May-Grünwald Giemsa (MGG) staining was used to analyze cytospins. Pictures were taken on an Olympus BX50 microscope (Olympus Nederland BV, Zoeterwoude, the Netherlands) with a 100×/1.3 oil objective. Pictures of MS5 cocultures and (Venus+) L-CAs were taken with a Leica DM-IL microscope (Leica Microsystems, Rijswijk, the Netherlands) with a 20×/0.30 or 40×/0.60 objective.

Replating of leukemic cultures

For assessment of self renewal, 200 000 AML cells were transduced and plated onto T25 flasks preplated with MS5 stromal cells. AML cells were expanded in LTC medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL IL-3, G-CSF, TPO, and 500 nM 4-OHT. At weeks 1, 3, and 5 of culture, fresh medium was added. At weeks 2, 4, and 6, all medium containing suspension cells was removed and analyzed by flow cytometry for the percentage of Venus-expressing cells. The remaining adherent cell layer, containing both MS5 cells and leukemic cobblestone area-forming cells (L-CAs), was washed twice with PBS and trypsinized for 15 minutes. All trypsinized cells were resuspended in 5 mL LTC medium, and 10% was replated onto T25 flasks preplated with fresh MS5 stromal cells. The remaining 90% was stained with PE-labeled anti-human CD45 (BD) to distinguish between mouse MS5 and human leukemic cells and was analyzed for Venus expression.

Results

Impaired DNA-binding capacity of C/EBPα in CD34+ AML cells

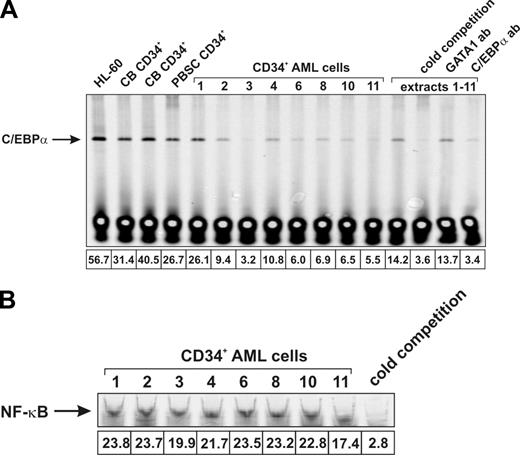

In order to study C/EBPα DNA binding in the primitive subfraction of AML cells, CD34+ AML cells, which have been demonstrated to possess AML-LTC-IC and L-CAFC activity22,24 (also D.v.G. et al, submitted manuscript) from FAB subtypes M1 (n = 3), M2 (n = 2), M4 (n = 1), and M5 (n = 5) were isolated and subjected to nuclear fractionation and gel shift (EMSA) experiments. A total of 7 of 11 AMLs tested were Flt3-ITD positive (63.6%; Table 1). Figure 1A demonstrates that DNA binding of C/EBPα in various AML samples is severely reduced compared with C/EBPα DNA binding from extracts of CB CD34+ cells, extracts of mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells, and the myeloid HL-60 cell line. Sorting of equal cell numbers was used to normalize protein content of the extracts. The gel shift analysis was specific for C/EBPα, since competition with an excess of unlabeled probe demonstrated a decrease in DNA binding activity (Figure 1A; cold competition). Furthermore, addition of a C/EBPα-specific antibody, but not a control antibody against GATA1, inhibited binding to the probe, demonstrating the presence of C/EBPα in the protein-DNA probe complex (Figure 1A). A total of 3 independent EMSA experiments were performed, and similar results were obtained in each experiment. To check the quality of nuclear extracts, EMSAs were performed using a NF-κB–specific probe. As shown in Figure 1B, NF-κB DNA binding was observed in these nuclear extracts, indicating that the reductions in C/EBPα DNA binding were not due to technical differences in nuclear extract preparation. These data show that the transcription factor C/EBPα has a reduced DNA-binding capacity in most of the patients with AML studied.

C/EBPα has impaired DNA-binding capacity in patients with AML. (A) DNA-binding experiment using a C/EBPα-specific probe with nuclear extracts of 25 000 sorted CD34+ AML cells. Nuclear extracts of 25 000 HL-60, 2 independent batches of CB CD34+ cells, and 1 batch of CD34+ cells isolated from the mobilized peripheral blood of an allogeneic donor are shown as control. Nuclear extracts taken from patient nos. 1 to 11 were mixed, and were used in cold competition experiments using 50-fold excess of unlabeled probe. Supershift experiments were performed with a C/EBPα-specific antibody as well as with control antibodies against GATA1. Data of a representative example of 3 independent experiments are shown. The intensity of C/EBPα DNA binding is indicated below the lanes. (B) EMSA experiment as in panel A, but now nuclear extracts were incubated with a NF-κB–specific probe. Cold competition experiments were performed using 50-fold excess of unlabeled probe.

C/EBPα has impaired DNA-binding capacity in patients with AML. (A) DNA-binding experiment using a C/EBPα-specific probe with nuclear extracts of 25 000 sorted CD34+ AML cells. Nuclear extracts of 25 000 HL-60, 2 independent batches of CB CD34+ cells, and 1 batch of CD34+ cells isolated from the mobilized peripheral blood of an allogeneic donor are shown as control. Nuclear extracts taken from patient nos. 1 to 11 were mixed, and were used in cold competition experiments using 50-fold excess of unlabeled probe. Supershift experiments were performed with a C/EBPα-specific antibody as well as with control antibodies against GATA1. Data of a representative example of 3 independent experiments are shown. The intensity of C/EBPα DNA binding is indicated below the lanes. (B) EMSA experiment as in panel A, but now nuclear extracts were incubated with a NF-κB–specific probe. Cold competition experiments were performed using 50-fold excess of unlabeled probe.

Summary of patient characteristics

| Patient no. . | BM/PB . | White blood cell counts, × 109/L . | % blasts In PB . | % CD34 . | Flt3-ITD . | FAB . | Karyotype . | Risk group . | C/EBPα transduction . | EMSA . | Q-PCR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PB | 30 | 90 | 14 | − | M2 | t(8;21) | Good | + | + | — |

| 2 | PB | 15 | 30 | 30 | + | M1 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | + |

| 3 | PB | 60 | 60 | 14 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 4 | PB | 20 | 50 | 70 | − | M1 | +3q, −7, −10 | Poor | + | + | — |

| 5 | PB | 100 | 90 | 2 | − | M1 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 6 | PB | 70 | 86 | 7 | − | M4 | t(6;11), (q27;23) | Poor | + | + | — |

| 7 | PB | 100 | 80 | 1 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 8 | PB | 84 | 80 | 5 | + | M5b | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 9 | PB | 47 | 36 | 1 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 10 | PB | 22 | 72 | 28 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 11 | PB | 63 | 67 | 66 | + | M1 | t(6;9), trisomy 13 | Poor | + | + | + |

| Patient no. . | BM/PB . | White blood cell counts, × 109/L . | % blasts In PB . | % CD34 . | Flt3-ITD . | FAB . | Karyotype . | Risk group . | C/EBPα transduction . | EMSA . | Q-PCR . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PB | 30 | 90 | 14 | − | M2 | t(8;21) | Good | + | + | — |

| 2 | PB | 15 | 30 | 30 | + | M1 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | + |

| 3 | PB | 60 | 60 | 14 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 4 | PB | 20 | 50 | 70 | − | M1 | +3q, −7, −10 | Poor | + | + | — |

| 5 | PB | 100 | 90 | 2 | − | M1 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 6 | PB | 70 | 86 | 7 | − | M4 | t(6;11), (q27;23) | Poor | + | + | — |

| 7 | PB | 100 | 80 | 1 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 8 | PB | 84 | 80 | 5 | + | M5b | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 9 | PB | 47 | 36 | 1 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | — | — |

| 10 | PB | 22 | 72 | 28 | + | M5 | Normal | Intermediate | + | + | — |

| 11 | PB | 63 | 67 | 66 | + | M1 | t(6;9), trisomy 13 | Poor | + | + | + |

Blasts isolated from bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood (PB). AMLs were categorized according to the French-American-British (FAB) classification. Positivity for Flt3-ITD is indicated as well as CD34 percentage, karyotype, and risk group. The right 3 columns indicate the experiments performed with the AMLs.

— indicates not done.

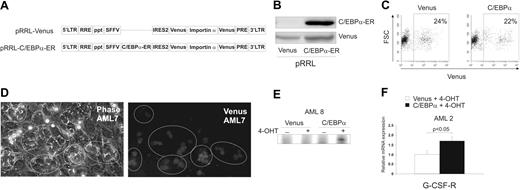

Efficient transduction of CD34+ AML cells using lentiviral vectors containing an inducible form of C/EBPα

In order to investigate the consequences of the reduced C/EBPα DNA binding, we used lentiviral vectors in order to reintroduce C/EBPα into human CD34+ AML cells (schematically depicted in Figure 2A). C/EBPα was fused to the estrogen receptor ligand-binding domain (ER) to create a 4-OHT–inducible form of C/EBPα, which was inserted in front of the IRES2 sequence. These vectors furthermore contained a Venus (an optimized yellow fluorescent protein [YFP] variant) cDNA fused to importin α sequences to target it to the nuclear envelope. Western blot analysis of CB CD34+-transduced cells demonstrated high expression from the spleen focus forming virus (SFFV) promoter (Figure 2B). Primary CD34+-sorted AML cells were transduced with efficiencies between 20% and 25% (Figure 2C). Fluorescence microscopy on MS5 cocultures showed the presence of Venus+ L-CAs (Figure 2D). As these L-CAs contained secondary and tertiary plating efficiency, these data indicate the technical ability to transduce an immature CD34+ cell fraction that contained self-renewal capacity (Figure 4A; data not shown). Venus+ AML cells were sorted and treated with 4-OHT for 1 week on MS5, after which nuclear extracts were subjected to gel shift analysis in order to verify the validity of our experimental setup. Figure 2E demonstrates DNA binding of exogenous C/EBPα-ER upon administration of 4-OHT. Furthermore, a Q-PCR analysis for the C/EBPα target gene G-CSF-R was performed on transduced AML cells to verify that the 4-OHT–induced DNA binding is also functional. As is depicted in Figure 2F, activation of C/EBPα-ER with 4-OHT induced an 1.7-fold up-regulation of G-CSF-R expression (P < .05) in primary CD34+ AML cells, indicating that C/EBPα is functionally active in our transduced leukemic cells.

Reintroduction of C/EBPα in AML CD34+ cells. (A) Schematic overview of the lentiviral overexpression vectors used in these studies. (B) Western blot analysis of C/EBPα-ER in CD34+ CB stem/progenitor cells. (C) Transduction efficiency of CD34+ AML cells. (D) Phase-contrast and Venus fluorescence (GFP channel) pictures indicating the presence of Venus+ CAs (circled) in week 2 leukemic MS5 cocultures. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.” (E) DNA-binding experiment to C/EBPα-specific probe with nuclear extracts of 50 000 CD34+ AML cells from MS5 cocultures treated for 1 week with or without 500 nM 4-OHT. (F) Q-PCR for the C/EBPα target gene G-CSF-R after 1 week of coculture on MS5 in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT. mRNA levels were normalized against GAPDH mRNA levels and C/EBPα-transduced values are shown relative to control Venus-transduced values. An average of 2 samples is shown with SEM.

Reintroduction of C/EBPα in AML CD34+ cells. (A) Schematic overview of the lentiviral overexpression vectors used in these studies. (B) Western blot analysis of C/EBPα-ER in CD34+ CB stem/progenitor cells. (C) Transduction efficiency of CD34+ AML cells. (D) Phase-contrast and Venus fluorescence (GFP channel) pictures indicating the presence of Venus+ CAs (circled) in week 2 leukemic MS5 cocultures. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.” (E) DNA-binding experiment to C/EBPα-specific probe with nuclear extracts of 50 000 CD34+ AML cells from MS5 cocultures treated for 1 week with or without 500 nM 4-OHT. (F) Q-PCR for the C/EBPα target gene G-CSF-R after 1 week of coculture on MS5 in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT. mRNA levels were normalized against GAPDH mRNA levels and C/EBPα-transduced values are shown relative to control Venus-transduced values. An average of 2 samples is shown with SEM.

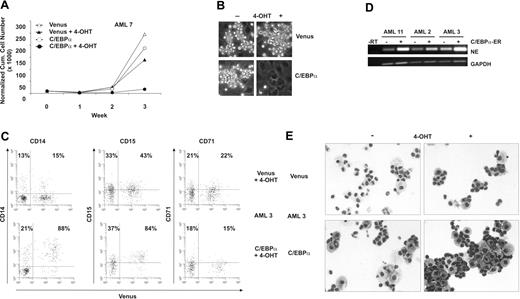

Restoration of C/EBPα expression in CD34+-sorted AML blasts induces a cell-cycle arrest, in conjunction with enhanced expression of CD14, CD15, and CD11b

Subsequent C/EBPα expression was restored by transduction of AML CD34+ cells, followed by plating onto MS-5 stromal cells in order to study proliferation, differentiation, and expansion (n = 7). Figure 3. A demonstrates a representative cumulative growth culture. Control cultures of Venus-transduced cells depicted a clear expansion over a period of 3 weeks, either in the presence or absence of 4-OHT, ranging from 3.9-fold expansion in AML no. 2 to an approximately 860-fold expansion in AML no. 8 (Table 2). C/EBPα-ER–transduced cultures demonstrated a similar expansion curve in the absence of 4-OHT. Addition of 4-OHT, to activate the C/EBPα transgene in these cultures, immediately led to a strong reduction of expansion of all AML cultures (n = 7; Table 2), reflected by a reduction of cumulative cell counts and a sharp decrease in the percentage of Venus-expressing cells in these cultures (Figure 3A; data not shown). Microscopic examination of the cultures verified these observations (Figure 3B). Sorting of Venus+ cells from expanding untreated control and C/EBPα-ER cultures and stimulating them with 4-OHT rapidly induced a growth arrest in C/EBPα-ER transduced cultures only, indicating a cell-intrinsic effect due to C/EBPα activation, rather than differences between growth cultures (data not shown).

C/EBPα-ER impairs growth and expansion and induces differentiation of leukemic cells. (A) Cumulative growth cultures of AML cells (n = 7) on MS5 cells in the presence or absence of 500 nM 4-OHT. Half of the cultures were harvested weekly, and fresh medium was added to the culture. A representative example (AML no. 7) is shown, and all expansion data are summarized in Table 2. (B) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of AML (no. 11) cocultures in the presence or absence of 500 nM 4-OHT on MS5 cells at week 3. Note the absence of phase bright suspension cells from C/EBPα-ER–transduced culture after treatment with 500 nM 4-OHT. One representative example is shown. (n = 7). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of suspension cells from week-1 leukemic MS5 cocultures in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT. One representative example is shown. Also refer to Table 2. Indicated are the percentages of CD14+, CD15+, or CD71+ cells within the Venus− or Venus+ fractions. (n = 7). (D) RT-PCR analysis of neutrophil elastase (NE) expression in 3 AML samples after treatment with 500 nM 4-OHT in Venus-transduced cells (−) or in C/EBPα-ER–transduced cells (+). GAPDH expression is shown as loading control. −RT-PCRs were performed as negative control. (E) Morphologic analysis of suspension cells at week 1 of AML no. 3 was performed by MGG staining of cytospins. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.”

C/EBPα-ER impairs growth and expansion and induces differentiation of leukemic cells. (A) Cumulative growth cultures of AML cells (n = 7) on MS5 cells in the presence or absence of 500 nM 4-OHT. Half of the cultures were harvested weekly, and fresh medium was added to the culture. A representative example (AML no. 7) is shown, and all expansion data are summarized in Table 2. (B) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of AML (no. 11) cocultures in the presence or absence of 500 nM 4-OHT on MS5 cells at week 3. Note the absence of phase bright suspension cells from C/EBPα-ER–transduced culture after treatment with 500 nM 4-OHT. One representative example is shown. (n = 7). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of suspension cells from week-1 leukemic MS5 cocultures in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT. One representative example is shown. Also refer to Table 2. Indicated are the percentages of CD14+, CD15+, or CD71+ cells within the Venus− or Venus+ fractions. (n = 7). (D) RT-PCR analysis of neutrophil elastase (NE) expression in 3 AML samples after treatment with 500 nM 4-OHT in Venus-transduced cells (−) or in C/EBPα-ER–transduced cells (+). GAPDH expression is shown as loading control. −RT-PCRs were performed as negative control. (E) Morphologic analysis of suspension cells at week 1 of AML no. 3 was performed by MGG staining of cytospins. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.”

Fold expansion and surface marker expression of Venus+ and C/EBPα+ cells after transduction

| Patient no. . | V1: fold expansion . | V2: antigen expression in culture, % . | Increase/decrease in V3 antigen expression, % . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14 . | CD15 . | CD71 . | CD11b . | CD36 . | CD14 . | CD15 . | CD71 . | CD11b . | CD36 . | ||

| 2 | +20 | +16 | ND | ND | ND | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 0.4 | 20 | 16 | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| 3 | +73 | +41 | −7 | ND | +19 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 28.0 | 15 | 43 | 22 | ND | 2 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 2.2 | 88 | 84 | 15 | ND | 21 | |||||

| 7 | +31 | −5 | −23 | ND | +2 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 87.5 | 38 | 41 | 37 | ND | 7 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 5.7 | 69 | 36 | 14 | ND | 9 | |||||

| 8 | +40 | +7 | −5 | +25 | +14 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 863.5 | 3 | 1 | 55 | 66 | 6 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 39.6 | 43 | 8 | 50 | 91 | 20 | |||||

| 9 | +10 | +34 | −13 | ND | −3 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 4.5 | 12 | 42 | 23 | ND | 7 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 0.4 | 22 | 76 | 10 | ND | 4 | |||||

| 10 | +16 | +11 | −7 | +29 | +7 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 16.3 | 15 | 0 | 27 | 63 | 3 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 1.5 | 31 | 11 | 20 | 92 | 10 | |||||

| 11 | +2 | −2 | −54 | +24 | −1 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 154.5 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 65 | 2 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 2.0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 89 | 1 | |||||

| Patient no. . | V1: fold expansion . | V2: antigen expression in culture, % . | Increase/decrease in V3 antigen expression, % . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14 . | CD15 . | CD71 . | CD11b . | CD36 . | CD14 . | CD15 . | CD71 . | CD11b . | CD36 . | ||

| 2 | +20 | +16 | ND | ND | ND | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 0.4 | 20 | 16 | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| 3 | +73 | +41 | −7 | ND | +19 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 28.0 | 15 | 43 | 22 | ND | 2 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 2.2 | 88 | 84 | 15 | ND | 21 | |||||

| 7 | +31 | −5 | −23 | ND | +2 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 87.5 | 38 | 41 | 37 | ND | 7 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 5.7 | 69 | 36 | 14 | ND | 9 | |||||

| 8 | +40 | +7 | −5 | +25 | +14 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 863.5 | 3 | 1 | 55 | 66 | 6 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 39.6 | 43 | 8 | 50 | 91 | 20 | |||||

| 9 | +10 | +34 | −13 | ND | −3 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 4.5 | 12 | 42 | 23 | ND | 7 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 0.4 | 22 | 76 | 10 | ND | 4 | |||||

| 10 | +16 | +11 | −7 | +29 | +7 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 16.3 | 15 | 0 | 27 | 63 | 3 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 1.5 | 31 | 11 | 20 | 92 | 10 | |||||

| 11 | +2 | −2 | −54 | +24 | −1 | ||||||

| Venus + 4OHT | 154.5 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 65 | 2 | |||||

| C/EBPα + 4OHT | 2.0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 89 | 1 | |||||

Expansion and surface marker expression after transduction. The calculated fold-expansion of transduced cells at week 4, as well as the percentages of cells positive for cell surface markers as measured by flow cytometry are indicated. The arrows indicate the difference in expression between control Venus-transduced cells treated with 500 nM 4-OHT and C/EBPα-ER-transduced cells after 1 week of coculture on MS5 cells.

nd indicates not determined.

Since growth arrest of hematopoietic cells is frequently accompanied by differentiation, flow cytometric analysis on suspension cells was performed after 1 week of culture to investigate the differentiation state of the leukemic CD34+ cells. Analysis of myeloid markers specific for monocytic/macrophage (CD14) and granulocytic (CD15) differentiation demonstrated an increase in the percentage of cells positive for CD14 in C/EBPα-ER–transduced cells compared with control cells or with nontransduced (Venus−) cells within the same culture, ranging from 2% to 73% (Figure 3C; Table 2). CD15 expression increased in 5 AML samples upon C/EBPα activation, ranging from 7% to 41%, whereas 2 AML samples showed a decrease of 2% and 5% of CD15 expression (Table 2). Whereas almost all investigated AML samples showed changes in the expression of CD14 and CD15, in some of those, CD36 changed also (Table 2). In 3 AML samples (nos. 8, 10, and 11), CD11b was investigated as well and demonstrated markedly increased expression (Table 2). In addition, a decrease in the percentage of CD71+ cells in C/EBPα-ER–activated cultures was observed, compared with control Venus-transduced cultures (Figure 3C; Table 2), although the degree of reduction ranged from 5% to 54% between AML samples (Table 2). This is in agreement with the observed growth arrest in expanding cultures, since CD71 is a marker of proliferating cells.25 RT-PCR studies demonstrated that C/EBPα-ER enhanced the expression of the C/EBPα target gene neutrophil elastase, which is induced upon granulocytic differentiation (Figure 3D).26

Morphologic analysis of MGG stains confirmed the flow cytometry data regarding enhanced differentiation in some of these AML samples (Figure 3E). Control Venus-transduced cells of AML no. 3 (FAB M5) showed an immature monocytic morphology, which did not change upon treatment with 4-OHT. C/EBPα-ER–transduced cells, however, showed the presence of more macrophage–like cells in untreated cultures, which was markedly increased upon activation of C/EBPα-ER with 4-OHT. Together, these data suggest that the absence of C/EBPα in AML cells contributes to the immature phenotype of these cells, which can be rescued partially by restoration of C/EBPα activation.

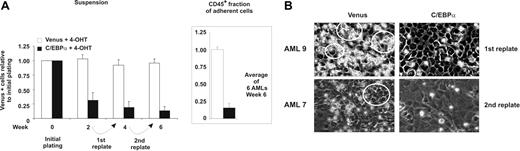

Restoration of C/EBPα activation in primitive leukemic cells decreases the self-renewal capacity

In order to investigate the self-renewal potential, we conducted serial replating experiments with the expanding AML cultures (n = 6). Sorted CD34+ AML cells were transduced with C/EBPα-ER or empty control vectors and plated onto MS5 stroma. Every 2 weeks, the suspension cells were removed from the cultures, and the adherent cell layer was washed 2 times and subsequently trypsinised. L-CAs are present in this adherent fraction, and contain self-renewal capacity as demonstrated by the capacity to generate new L-CAs upon each sequential replating onto new stromal cell layers, a feature that is absent from normal CD34+ cells (D.v.G. et al, submitted manuscript). Furthermore, the leukemic origin of the expanded cells was established by the fact that AML CD34+ cells were isolated from the peripheral blood (PB; Table 1), which contains normal CD34+ cells only at very low frequencies, and by the fact that mutations such as FLT3-ITDs persisted in the replated L-CAs (D.v.G. et al, submitted manuscript). A total of 10% of the adherent AML cells were replated, and after 2 subsequent weeks of culture, the percentage of Venus-expressing cells was determined in the suspension fraction and within the CD45+ fraction of the trypsinised adherent MS5 cell layer.

The average of 6 independent AML experiments is shown in Figure 4A. Unsorted cells were expanded on MS5, and cell counts and the percentage of Venus+ cells was established weekly by FACS. The relative expansion of Venus+ cells is shown, where the cell number at initial plating is set to 1. At week 2, the expansion of Venus+ cells was comparable with the expansion of nontransduced cells, and thus the relative number of Venus+ cells in suspension remained stable (Figure 4A). The adherent L-CAs that had formed were replated onto new MS5 stroma, and these cells readily gave rise to second L-CAs (Figure 4B) that were capable of generating progeny in suspension (Figure 4A,B). Again, at week 4, no differences were observed in the expansion of Venus+ cells versus nontransduced cells in suspension, and the second L-CAs could be harvested to give rise to third L-CAs upon second replating (Figure 4A,B). At week 6, the relative number of Venus+ cells was determined in both the suspension as well as adherent fraction, and in both populations, Venus+ cells behaved comparable with nontransduced cells.

C/EBPα-ER impairs self-renewal of leukemic cells. (A) Transduced AML cells were subjected to serial replating experiments in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT (n = 6) with cells from the adherent fraction. Every 2 weeks suspension cells were removed and analyzed by flow cytometry for Venus expression. The relative number of Venus+ cells in suspension cultures at initial plating (week 0) are set to 1, and subsequent weeks are shown relative to initial plating. The relative number of Venus+ cells within the adherent human CD45+ fraction was analyzed as well, where the number of Venus control adherent cells was set to 1 (box on the right). A total of 10% of the adherent fraction was replated onto fresh MS5 cultures, which were maintained for another 2 weeks, followed by a second replate. The average with SEM from 6 individual AML samples is shown. Venus percentages in suspension cultures at initial plating (week 0) are set to 1, and subsequent weeks are shown relative to initial plating. (B) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of AML cocultures in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT on MS5 cells after the first replate at week 4 (top row; AML no. 9), or after the second replate at week 6 (bottom row; AML no. 7). CAs are circled. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.”

C/EBPα-ER impairs self-renewal of leukemic cells. (A) Transduced AML cells were subjected to serial replating experiments in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT (n = 6) with cells from the adherent fraction. Every 2 weeks suspension cells were removed and analyzed by flow cytometry for Venus expression. The relative number of Venus+ cells in suspension cultures at initial plating (week 0) are set to 1, and subsequent weeks are shown relative to initial plating. The relative number of Venus+ cells within the adherent human CD45+ fraction was analyzed as well, where the number of Venus control adherent cells was set to 1 (box on the right). A total of 10% of the adherent fraction was replated onto fresh MS5 cultures, which were maintained for another 2 weeks, followed by a second replate. The average with SEM from 6 individual AML samples is shown. Venus percentages in suspension cultures at initial plating (week 0) are set to 1, and subsequent weeks are shown relative to initial plating. (B) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of AML cocultures in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT on MS5 cells after the first replate at week 4 (top row; AML no. 9), or after the second replate at week 6 (bottom row; AML no. 7). CAs are circled. See “Materials and methods; Microscopy and cytospins.”

In contrast to control Venus-transduced cells, the relative number of C/EBPα-ER–transduced cells in suspension dropped significantly compared with nontransduced controls (Figure 4A,B). This coincided with a reduction in the number of L-CAs that were formed in the initial plating (data not shown). Importantly, those remaining L-CAs were impaired in their replating capacity, as no expanding second cultures could be established with these cells, and strongly reduced numbers of C/EBPα-ER+ cells were detected upon each replating, both in suspension as well as in the adherent population (Figure 4A). While second and even third L-CAs were readily observed in Venus control cultures, these L-CAs were absent from replated C/EBPα-ER cultures (Figure 4B). Collectively, these data indicate that restoration of C/EBPα activity in primitive AML CD34+ cells decreases their self-renewal capacity.

In view of the declining self-renewal potential and the induced growth arrest, we studied expression of cell-cycle regulators by Q-PCR analysis. CD34+ cells from AML sample nos. 2 and 11 were transduced with Venus control vectors or C/EBPα, GFP+ cells were sorted by MoFlo, and RNA was extracted for Q-PCRs. As shown in Figure 5, C/EBPα was appropriately overexpressed. PIM1 expression was unaffected in AML no. 2, and was not expressed at all in AML no. 11, while PIM2 was reduced upon C/EBPα expression. Cyclin D1 was reduced in AML no. 2, and cyclin D2 was reduced in both AML nos. 2 and 11 upon C/EBPα expression. Of the cell cycle–dependent kinases (CDKs) under investigation, CDK6 was significantly reduced in both AMLs by C/EBPα, while CDK2 and CDK4 remained unaffected. Of the CDK inhibitors (CDKi's), p21 was the most dominantly up-regulated CDKi in AML no. 2, while p57 was the predominantly up-regulated CDKi in AML no. 11. No changes were observed in p27 expression. These data indicate that cell-cycle progression is impaired at various stages by C/EBPα overexpression, but that differences between AMLs exist as well regarding the target genes that are being affected. A striking observation was that the receptor for stem cell factor, c-Kit, was strongly down-modulated by C/EBPα in both AML samples. Last, expression of antiapoptosis genes was also investigated. While no differences in Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL expression were observed in AML no. 11, a significant down-modulation of these genes was observed in AML no. 2 upon C/EBPα expression. These data suggest that an increase in apoptosis upon C/EBPα overexpression might underlie the reduction in expansion on MS5 of AML no. 2 as well.

Q-PCR analysis on transduced AML CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells from AML nos. 2 and 11 were transduced with Venus control vectors or C/EBPα and plated on MS5 for 1 week in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT, after which GFP+ cells were sorted by MoFlo and RNA was extracted for Q-PCRs as indicated. GAPDH expression was used as internal control, and the expression levels were normalized to 1 in the Venus control groups. Error bars denote the standard deviations, belonging to the normalized means as they are shown. ND indicates not detectable, expression was below detection threshold.

Q-PCR analysis on transduced AML CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells from AML nos. 2 and 11 were transduced with Venus control vectors or C/EBPα and plated on MS5 for 1 week in the presence of 500 nM 4-OHT, after which GFP+ cells were sorted by MoFlo and RNA was extracted for Q-PCRs as indicated. GAPDH expression was used as internal control, and the expression levels were normalized to 1 in the Venus control groups. Error bars denote the standard deviations, belonging to the normalized means as they are shown. ND indicates not detectable, expression was below detection threshold.

Discussion

Impairments in C/EBPα signaling such as reduced mRNA or protein expression, aberrant phosphorylation profiles, or the presence of (dominant-negative) mutations are often observed in human myeloid leukemias.8–12,16,18 We studied DNA-binding activities of C/EBPα throughout a panel of patients with AML and showed that C/EBPα DNA binding was reduced. On the basis of our rescue experiments in which C/EBPα was reintroduced into primary human CD34+ AML blasts, we conclude that restoration of C/EBPα expression in AML blasts is sufficient to inhibit both leukemic expansion as well as self-renewal of the L-CA–forming stem cell pool. In concert with the pronounced proliferation block, a partially restored differentiation program was observed by C/EBPα reintroduction.

Our data suggest that loss of C/EBPα function facilitates the self-renewal capacity of leukemic stem cells. In our C/EBPα-transduced cultures, L-CAs were only rarely observed. Serial replating experiments established an impaired self-renewal potential, as second and third cultures could for the most part not be initiated. In contrast, the L-CAs that were generated from control-transduced cells contained self-renewal capacity as demonstrated in serial replating experiments. New L-CAs were generated upon sequential replating onto new bone marrow stromal cell layers, and a robust leukemic expansion was obtained. Mouse knockout studies have already shown that C/EBPα deficiency enhances the self-renewal and repopulating capacity of HSCs. This results in hyperproliferation of hematopoietic progenitors and blocks the transition from the CMP to the GMP stage.4,6 In normal human stem/progenitor cells, overexpression of C/EBPα resulted in exhaustion of the stem/progenitor cell pool, while myelopoiesis is induced at the expense of erythropoiesis21,27 (A.T.J.W., H.S., E.V., and J.J.S, unpublished observations, January 2006). Together, these observations firmly establish C/EBPα as a critical regulator of stem/progenitor cell fate in both mice and humans.

Recently, C/EBPα was also reintroduced into primary chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells at blast crisis, and although self-renewal of the stem cell compartment was not addressed upon C/EBPα reintroduction, myelopoiesis was restored upon IL-3 or G-CSF treatment.28 These data coincide with our observations in our primary AML models in which myelopoiesis was also partially restored upon re-expression of C/EBPα. Besides these primary human leukemic models, a number of (mostly mouse) leukemic cell-line models have been established in which it was demonstrated that forced expression of C/EBPα induced cell-cycle arrest, inhibited proliferation, and induced differentiation.14,28 Previously, we demonstrated that expression of activated STAT5 in human CD34+ stem/progenitor cells resulted in enhanced self-renewal and impaired myelopoiesis. This coincided with a strong downmodulation of C/EBPα expression.20 Importantly, re-expression of C/EBPα in this model strongly alleviated STAT5A(1*6)–induced self-renewal, while myelopoiesis was restored.21 In line with these observations, we and others have observed that expression of FLT3-ITD mutants can also result in a strong down-modulation of C/EBPα expression (our unpublished observations [January 2004] and Zheng et al14 and Moore et al29 ). Our current data in AML CD34+ cells indicates that the presence of FLT3-ITDs coincides with low C/EBPα DNA-binding activity, although additional mechanisms should exist as well since down-modulation of C/EBPα DNA binding was also observed in some patients with AML with wt FLT3. A recent report indicated that C/EBPα transactivation can be down-modulated by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of serine 21,16 but whether this also involves reduced C/EBPα DNA binding requires further studies. Together, these data firmly establish the importance of disturbed C/EBPα signal transduction in a variety of hematologic malignancies and pinpoint to the therapeutic potential of restoring C/EBPα activity in both acute and chronic myeloid leukemia.

As it is likely that disturbed C/EBPα signaling is only 1 of multiple factors involved in the pathogenesis of AML, it is not surprising that not all tested AML samples demonstrated a similar pattern. All investigated AML samples responded with a growth arrest and decreased expansion, while restoration of the differentiation program was much more variable, suggesting that cell-cycle arrest and differentiation are not affected in a similar fashion by the leukemic transformation. Experiments with various mutants of C/EBPα have indeed established that cell-cycle arrest is required, but not sufficient for granulocytic differentiation,30 while the reverse experiment indicated that loss of cell-cycle control is sufficient to initiate AML-like transformation.31 When (partial) differentiation was restored, in most patients, both CD14 and CD15 were up-regulated. This is consistent with findings that C/EBPα controls the CMP-to-GMP transition, but is not required beyond the GMP stage.6 Therefore, it is not surprising that monocytic differentiation can be observed upon activation of C/EBPα. While C/EBPα deficiency had already been shown to block macrophage development,4 only recently was C/EBPα shown to direct monocytic commitment, presumably through up-regulation of PU.1 mRNA.5,32 Although we did not detect an up-regulation of PU.1 mRNA in that particular AML, preliminary observations in CB CD34+-transduced cells with C/EBPα indicated elevated expression of PU.1 (data not shown). The question by which mechanisms low C/EBPα levels enhance self-renewal of stem cells remains to be addressed. Our Q-PCR analyses do reveal that the receptor for stem cell factor, c-Kit, is strongly down-modulated by re-expression of C/EBPα. Also, various genes that control cell-cycle progression are under the control of C/EBPα in AML CD34+ cells, including cyclin D1, cyclin D2, CDK6, and the cell cycle–dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p57. Although heterogeneity presumably exists throughout AML samples as our Q-PCR analyses also indicate, it is well plausible that low C/EBPα expression levels in the leukemic stem cell allow cell-cycle progression and alter the fate of the stem cell progeny such that the balance between differentiation and self-renewal is shifted toward the latter, at the expense of appropriate myelopoiesis.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that reintroduction of C/EBPα in primary CD34+ AML cells leads to a rapid growth arrest, which in some instances is paralleled by an enhanced differentiation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that C/EBPα activation in the leukemic stem cells leads to a loss of self-renewal capacity, thereby indicating the important function of loss of C/EBPα in the event of leukemogenesis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Geert Mesander and Henk Moes for help with flow cytometry; Dr C. Baum from the Department of Experimental Hematology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany, for the kind gifts of pRRL-Venus vector; and Amgen and Kirin for providing cytokines. The authors greatly appreciate the help of Dr A. van Loon, Dr J. J. Erwich, and colleagues (Obstetrics departments from the Martini Hospital and UMCG) for collecting cord blood.

This work was supported by Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) grant RUG 2000-2004 to E.V. and a Nederlandse organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)-VENI (2004-2008) grant to J.J.S.

Authorship

Contribution: H.S. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.T.J.W. contributed analytic tools and performed research; D.v.G. contributed analytic tools and performed research; B.J.L.E. analyzed data; E.V. designed research and analyzed data; and J.J.S. designed research and analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jan Jacob Schuringa, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen, Hanzeplein 1, 9713 GZ Groningen, the Netherlands; e-mail: j.schuringa@int.umcg.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal