Abstract

In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), previous studies have suggested that, while concordant bone marrow (BM) involvement confers a poor prognosis, discordant BM involvement does not. Whether this correlation is independent of the non-Hodgkin lymphoma International Prognostic Index (IPI) was previously unknown. We reviewed all DLBCL case histories from 1986 to 1997 at our center with complete staging, IPI data, and follow-up. A total of 55 (11.2%) of 489 patients had BM involvement, including 29 with concordant involvement and 26 with discordant involvement. The 55 patients with BM involvement had a poor prognosis compared with the uninvolved BM group (5-year overall survival [OS], 34.5% versus 46.9%; log-rank P = .019). However, concordant involvement portended a very poor prognosis (5-year OS, 10.3%; P < .001), whereas discordant involvement did not (5-year OS, 61.5%, P value nonsignificant). Compared with the discordant subset, the concordant subset patients were older, had a higher serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and a significantly higher IPI. However, the poor survival associated with concordant BM involvement was independent of the IPI score (P = .002, Cox regression). We conclude that in patients with DLBCL, concordant but not discordant BM involvement confers a very poor clinical outcome. Furthermore, concordant BM involvement is an independent adverse prognostic factor.

Introduction

Bone marrow (BM) involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is often discordant, characterized by a BM infiltrate composed of small lymphoid cells with cleaved nuclear contours admixed with only rare large transformed lymphoid cells, morphologically suggestive of a coexisting low-grade lymphoma.1–5 The mechanism for the morphologic discordance remains unclear but may involve transformation of a low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or alternatively the presence of 2 unrelated B-cell neoplasms.6 This is in contrast to DLBCL with concordant BM involvement, where the marrow lymphoid infiltrates are composed of a prominent component of large transformed lymphoid cells. Various groups have shown that concordant BM involvement carries a poor prognosis, whereas discordant BM involvement does not.1–5 Interestingly, discordant BM involvement in large-cell lymphoma may be associated with higher rates of late relapse.3

The non-Hodgkin lymphoma International Prognostic Index (IPI) is a powerful tool for predicting clinical outcome in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma on the basis of clinical criteria, including age, stage, extranodal site involvement, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, and performance status.7 Most of the previous studies examining prognosis in DLBCL with BM involvement were small and predated the introduction of the IPI, thus making interpretation difficult. Therefore, until now it has remained unclear whether concordant BM involvement in DLBCL is independent of the IPI in terms of survival prediction.

The intent of the present study was to examine the prognostic impact of concordant versus discordant BM involvement in DLBCL while controlling for the IPI. We have found that DLBCL with concordant BM involvement carries a poor prognosis that is independent of the IPI, whereas discordant BM involvement does not confer poor prognosis.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient population

A total of 624 consecutive patients with DLBCL initially diagnosed from 1986 to 1997 at the Cross Cancer Institute (Edmonton, AB, Canada) were reviewed. Of these, 489 patients had complete clinical and pathologic data for analysis and were therefore included in this study. Clinical data included staging according to the Ann Arbor system and scoring using the IPI criteria. All patients in our series were evaluated with history and physical examination, computed tomography (CT) scanning, complete blood count (CBC), LDH, serum biochemistry including liver enzymes and renal function, and BM biopsy. Some patients also had plain radiographs, lymphangiography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scans, lumbar puncture, or other investigations as clinically indicated. Treatment protocols during this time period were in keeping with international standards and generally included intensive combination chemotherapy regimens (CHOP [cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone]–like regimens) for front-line therapy, and salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation. Institutional Review Board approval for this study was granted by the Alberta Cancer Board Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Determination of BM involvement

All BM biopsy samples were reviewed in this study by a hematopathologist (R.L.) for the presence or absence of BM involvement, extent of infiltration, and histology of the lymphoid infiltrates (ie, discordant versus concordant marrow involvement). The criteria used to distinguish benign lymphoid infiltrates from lymphomatous involvement have been described in detail elsewhere.8 Determination of the histology of the lymphoid infiltrates was adopted and modified from a previously published method,3 which defined BM involvement as small-cell type, mixed-cell type, and large-cell type using the criteria of less than 5, 5 to 15, and more than 15 large, noncleaved cells per high-power field, respectively, in a background of small cleaved cells. Since our initial analysis revealed that patients with the mixed-cell type of BM involvement were relatively uncommon and were similar prognostically to those with large-cell involvement, we combined patients with the mixed-cell type and large-cell type in 1 group. Thus, in this study, we defined concordant marrow involvement when there were less than 5 large, noncleaved cells per high-power field, and discordant marrow involvement when there were 5 or more large, noncleaved cells per high-power field. The extent of the marrow involvement was estimated based on the proportion of marrow space occupied by the neoplasm.

Statistical analysis

Univariate correlations between BM involvement and other known prognostic factors were examined at the time of diagnosis. Student t test, Fisher exact test, or the chi-squared test was used as appropriate. Overall survival (OS) was determined from the date of initial diagnosis until death from any cause or to last follow-up evaluation for survivors. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival distributions were compared with the log-rank test. Cox regression was used to assess the contribution of BM involvement to prognosis. Statistical significance was set at a P value of .05 or less (2-sided).

Results

Patient characteristics and prevalence of BM involvement

For the 489 patients with DLBCL who had complete data, median follow-up was 995 days. A total of 55 (11.2%) had BM involvement. Of these 55 patients, 29 (52.7%) had concordant BM involvement (including 9 with mixed-cell type and 20 with large-cell BM involvement) and 26 (47.3%) had discordant BM involvement. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics for each of these 2 groups. Patients with concordant BM involvement (mean, 68.3 years; range, 41-92 years) were older than patients without BM involvement (mean, 60.4 years; range, 3-94 years) and were also older than patients with discordant BM involvement (mean, 60.3 years; range, 41-85 years). Patients with BM involvement had higher IPI scores because both stage and extranodal site scores reflect BM involvement, but also because LDH elevation was more prevalent in this group compared with the BM-negative group. There was no significant difference in sex, age, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status between the BM-involved versus BM-uninvolved groups. Patients with concordant BM involvement were older (P = .05) and more often had elevated LDH levels (P = .008) and higher IPI scores (P < .001) than patients with discordant BM involvement. No significant difference was noted for sex, stage, extranodal sites, and performance status between these 2 groups. Table 1 also includes an assessment of stage that excludes the BM status, and a tabulation of the number of extranodal sites other than the marrow; for both of these modified parameters, there was no significant difference among the groups.

Comparison of clinical features in the BM−, BM+, concordant BM+, and discordant BM+ groups

| Clinical features . | BM−, n = 434 . | BM+, n = 55 . | Concordant BM involvement, n = 29 . | Discordant BM involvement, n = 26 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male, no. (%) | 231 (53.2) | 25 (45.5) | 11 (37.9) | 14 (53.8) |

| Female, no. | 203 | 30 | 18 | 12 |

| Age | ||||

| 60 y and younger, no. (%) | 183 (42.2) | 19 (34.5) | 6 (20.7)* | 13 (50)† |

| Older than 60 y, no. | 251 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| Stage | ||||

| 1-2, no. (%) | 261 (60.1) | 0 (0)‡ | 0 (0)* | 0 (0) |

| 3-4, no. | 173 | 55 | 29 | 26 |

| Stage, excluding BM status | ||||

| 1-2, no. (%) | 261 (60.1) | 38 (69.1) | 19 (65.5) | 19 (73.1) |

| 3-4, no. | 173 | 17 | 10 | 7 |

| Extranodal sites | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 386 (88.9) | 33 (60.0)‡ | 16 (55.2)* | 17 (65.4) |

| 2 or more, no. | 48 | 22 | 13 | 9 |

| Extranodal sites, excluding BM | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 386 (88.9) | 51 (92.7) | 25 (86.2) | 26 (100) |

| 2 or more, no. | 48 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| LDH | ||||

| Normal, no. (%) | 219 (50.5) | 19 (34.5)‡ | 6 (20.7)* | 13 (50)† |

| Elevated, no. | 215 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 380 (87.6) | 45 (81.8) | 22 (75.9) | 23 (88.5) |

| 2-4, no. | 54 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| IPI score, no. (%) | ||||

| Low (0-1) | 203 (46.8) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) |

| Intermediate (2-3) | 198 (45.6) | 41 (74.5) | 20 (70.0) | 21 (80.8) |

| High (4-5) | 33 (7.6) | 12 (21.8)‡§ | 9 (31.0)*§ | 3 (11.5)†§ |

| Clinical features . | BM−, n = 434 . | BM+, n = 55 . | Concordant BM involvement, n = 29 . | Discordant BM involvement, n = 26 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male, no. (%) | 231 (53.2) | 25 (45.5) | 11 (37.9) | 14 (53.8) |

| Female, no. | 203 | 30 | 18 | 12 |

| Age | ||||

| 60 y and younger, no. (%) | 183 (42.2) | 19 (34.5) | 6 (20.7)* | 13 (50)† |

| Older than 60 y, no. | 251 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| Stage | ||||

| 1-2, no. (%) | 261 (60.1) | 0 (0)‡ | 0 (0)* | 0 (0) |

| 3-4, no. | 173 | 55 | 29 | 26 |

| Stage, excluding BM status | ||||

| 1-2, no. (%) | 261 (60.1) | 38 (69.1) | 19 (65.5) | 19 (73.1) |

| 3-4, no. | 173 | 17 | 10 | 7 |

| Extranodal sites | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 386 (88.9) | 33 (60.0)‡ | 16 (55.2)* | 17 (65.4) |

| 2 or more, no. | 48 | 22 | 13 | 9 |

| Extranodal sites, excluding BM | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 386 (88.9) | 51 (92.7) | 25 (86.2) | 26 (100) |

| 2 or more, no. | 48 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| LDH | ||||

| Normal, no. (%) | 219 (50.5) | 19 (34.5)‡ | 6 (20.7)* | 13 (50)† |

| Elevated, no. | 215 | 36 | 23 | 13 |

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0-1, no. (%) | 380 (87.6) | 45 (81.8) | 22 (75.9) | 23 (88.5) |

| 2-4, no. | 54 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| IPI score, no. (%) | ||||

| Low (0-1) | 203 (46.8) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) |

| Intermediate (2-3) | 198 (45.6) | 41 (74.5) | 20 (70.0) | 21 (80.8) |

| High (4-5) | 33 (7.6) | 12 (21.8)‡§ | 9 (31.0)*§ | 3 (11.5)†§ |

Statistically significant difference between concordant BM and BM-negative groups (P < .05).

Statistically significant difference between discordant BM and concordant BM groups (P < .05).

Statistically significant difference between BM-positive and BM-negative groups (P < .05).

Significant differences between 2 groups regarding IPI status were determined using 3 × 2 tables and the chi-squared test.

Prognostic significance of BM involvement

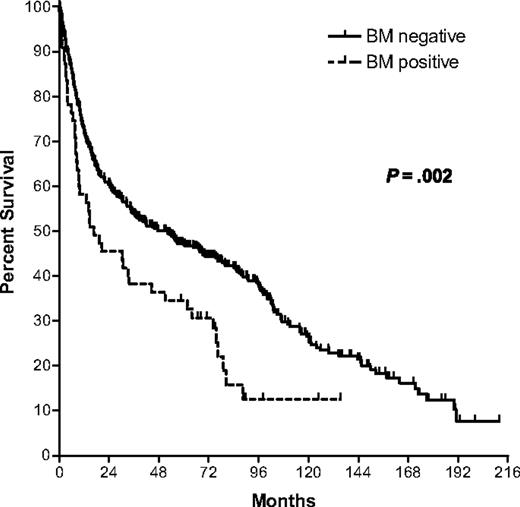

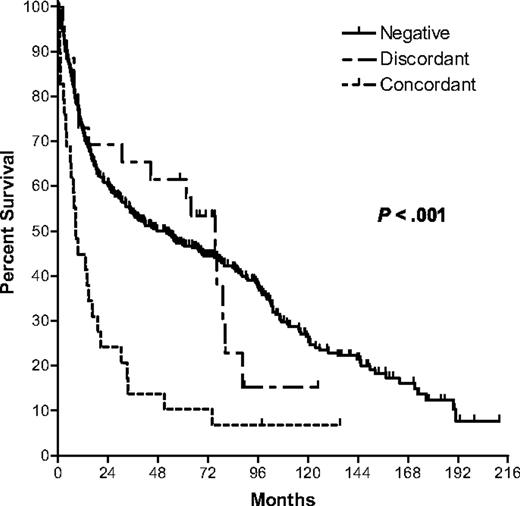

BM involvement predicted poor survival compared with the uninvolved BM group (5-year OS, 34.5% versus 46.9%; log-rank P = .019; Figure 1). Importantly, concordant BM involvement portended a very poor prognosis relative to patients without BM involvement (5-year OS, 10.3%; log-rank P < .001) whereas discordant BM involvement did not (5-year OS, 61.5%; log-rank P value nonsignificant; Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing BM-negative versus BM-positive groups.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing BM-negative, BM-discordant, and BM-concordant groups.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing BM-negative, BM-discordant, and BM-concordant groups.

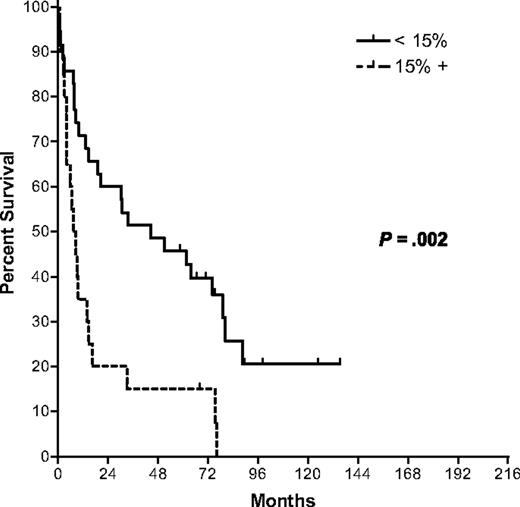

Extensive BM involvement was found to be a highly significant negative prognostic factor. For the purposes of this analysis, we defined extensive BM involvement at 15% and higher because this cutoff was most prognostically significant in our patient cohort on univariate analysis (5-year OS, 15.0% versus 45.7%; log-rank P = .002; Figure 3). The concordant subset had more patients with extensive BM involvement when compared with the discordant subset (51.7% versus 19.2%; P = .01; Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing patients by extent of BM involvement.

The extent of BM involvement in concordant versus discordant BM groups

| . | Concordant BM involvement, n = 29 . | Discordant BM involvement, n = 26 . |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal extent of BM involvement < 15%, no. (%) | 14 (48.3) | 21 (80.8)* |

| Extensive BM involvement ≥ 15%, no. (%) | 15 (51.7) | 5 (19.2) |

| . | Concordant BM involvement, n = 29 . | Discordant BM involvement, n = 26 . |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal extent of BM involvement < 15%, no. (%) | 14 (48.3) | 21 (80.8)* |

| Extensive BM involvement ≥ 15%, no. (%) | 15 (51.7) | 5 (19.2) |

Statistically significant difference between concordant and discordant BM groups (Fisher exact test, P < .05).

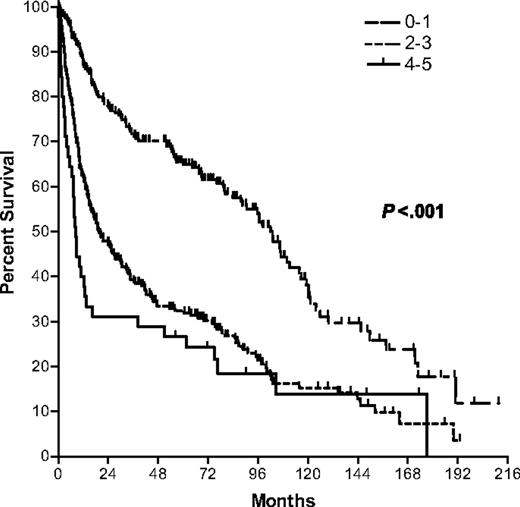

Multivariate analysis incorporating IPI

The IPI was predictive of OS, with low (0-1), low-intermediate (2), high-intermediate (3), and high (4-5) risk groups having 5-year survivals of 64.7%, 38.2%, 24.3%, and 26.7%, respectively (Figure 4). Patients with concordant BM involvement had higher IPI scores compared with patients without BM involvement (P < .001), partly by definition and partly owing to their aforementioned older age and increased LDH levels (Table 1). To clarify the impact of concordant BM involvement, multivariate analysis was carried out to control for IPI. A Cox regression model of OS was constructed including IPI and BM status as covariates. Based on this analysis, concordant BM involvement was a negative prognostic feature independent of the IPI score (hazard ratio compared with BM-negative patients = 1.87; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25-2.81; P = .002).

Discussion

We found that the prognostic significance of BM involvement in DLBCL is dependent on the morphologic cell type at this site. Whether this correlation is independent of the IPI was previously unknown. Of the published studies examining the prognostic significance of concordant versus discordant BM involvement in large-cell lymphoma, it is worth noting that the analysis of some studies included patients with various types of aggressive lymphoma in addition to DLBCL, and that the number of such patients in each series was relatively small, ranging from 50 to 180 patients.1–5 In addition, most of these papers were published in the era preceding the development of the IPI; the 1 paper in the post-IPI era included only 60 patients, and the authors recommended confirmation in a larger series.2

The IPI was originally defined and published in 1993 based on mathematical modeling of candidate prognostic factors in 2031 patients with de novo, diffuse aggressive lymphoma.7 BM involvement was considered for inclusion in the IPI (and ultimately rejected based on multivariate analysis), but the definitive study on this topic did not report on the extent to which the BM biopsies from these patients were reviewed.7 Despite the fact that it was intended to report only on patients with de novo aggressive lymphoma in the original IPI study, it remains possible that many of those patients had discordant BM involvement. This seems likely, given that the proportion of patients in that study reported to have BM involvement was 22%. In our present series, 11% of patients had BM involvement, and only half of these patients had concordant BM involvement. Even at our own center, the concordance or discordance of the marrow involvement was not routinely reported, particularly in the 1980s and early 1990s, and it was only upon direct review of the archived BM specimens that we were able to determine which cases of BM involvement were concordant or discordant.

We chose to study patients from the era prior to the introduction of rituximab in the treatment of DLBCL, and patients in our series received treatment that was comparable to the treatment given to patients in the original 1993 IPI study. We do not yet have enough follow-up on patients at our center treated with rituximab-containing regimens to make a determination of the prognostic impact of BM involvement in these patients, which are expected to have improved outcome relative to the patients reported here.9

The IPI was able to discriminate subgroups of patients with differing prognosis in our study, reaffirming the utility of the IPI in the evaluation of patients with DLBCL. Our 5-year OS estimates for the patient subgroups defined by the IPI are comparable to those cited in the original 1993 IPI study and confirmed by others.7,10,11 Despite the strong correlation between the presence of marrow involvement and IPI score, multivariate analysis revealed that concordant BM involvement is a negative prognostic factor independent of the IPI. Therefore, the presence of concordant BM involvement should be considered in the evaluation of prognosis of patients with DLBCL in addition to the IPI.

Interestingly, extensive (≥ 15%) BM involvement was more often seen with concordant rather than discordant BM involvement. Therefore, when extensive BM involvement is present, there should be heightened concern that concordant BM involvement is also present, and vice versa.

Of 489 patients with DLBCL, 55 (11.2%) had BM involvement. Others have reported BM involvement rates in their diffuse large-cell lymphoma population studies between 17% and 33%.1,5,7 This discrepancy may reflect differences in study populations, or variations in biopsy sampling and reporting methods. Our population represents the vast majority of patients DLBCL from our geographic region that underwent BM biopsy at a single institution for staging purposes. Therefore, there may be less selection bias in our study compared with previous reports that are referral population based. Importantly, most previously reported series included aggressive lymphomas other than DLBCL in the analysis, which may have affected the rate of marrow positivity in those studies.

Our study has potential limitations. At our center, BM biopsies are routinely unilateral, which might have reduced the sensitivity of the test for the detection of marrow involvement. This was a retrospective study that included patients from the era prior to the introduction of the IPI, and so not all patients during this time period had complete data for inclusion in our study. We did not have reliable information on the rates of relapse or causes of death in all patients, and so we could not compute relapse-free survival or cause-specific mortality. This is a single-institution study that may not completely reflect the experience of other centers. Despite these limitations, the findings from this large study are statistically robust and consistent with prior, smaller studies in its findings.

In summary, we found that concordant BM involvement with large cells in DLBCL is a negative prognostic feature that is independent of the IPI, although the 2 parameters are correlated. Identification of large cells in the BM is often associated with extensive BM involvement. On the other hand, discordant BM involvement had no adverse effect on survival in our study. These findings are confirmed here in a large series of patients and should be considered when assessing patient prognosis and when considering inclusion criteria for clinical trials. Future studies will address the impact of rituximab on the poor prognosis associated with BM involvement, and on the relationship between BM involvement and newer, molecular predictors of clinical outcome.10,11

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Clinical Investigator award from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (T.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.C. and T.R. contributed to study design, analysis, and writing. R.L. contributed to study design and analysis, and performed the pathology reviews. P.W. and J.L. contributed to study design and data collection/analysis. J.H. contributed to study design and statistical analysis. A.R.B. and A.R.T. treated many of the patients in this study and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tony Reiman, Cross Cancer Institute, 11560 University Ave, Rm 2229, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 1Z2; e-mail: tonyreim@cancerboard.ab.ca.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal