Novel therapeutic strategies are needed to address the emerging problem of imatinib resistance. The histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) is being evaluated for imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and has multiple cellular effects, including the induction of autophagy and apoptosis. Considering that autophagy may promote cancer cell survival, we hypothesized that disrupting autophagy would augment the anticancer activity of SAHA. Here we report that drugs that disrupt the autophagy pathway dramatically augment the antineoplastic effects of SAHA in CML cell lines and primary CML cells expressing wild-type and imatinib-resistant mutant forms of Bcr-Abl, including T315I. This regimen has selectivity for malignant cells and its efficacy was not diminished by impairing p53 function, another contributing factor in imatinib resistance. Disrupting autophagy by chloroquine treatment enhances SAHA-induced superoxide generation, triggers relocalization and marked increases in the lysosomal protease cathepsin D, and reduces the expression of the cathepsin-D substrate thioredoxin. Finally, knockdown of cathepsin D diminishes the potency of this combination, demonstrating its role as a mediator of this therapeutic response. Our data suggest that, when combined with HDAC inhibitors, agents that disrupt autophagy are a promising new strategy to treat imatinib-refractory patients who fail conventional therapy.

Introduction

Imatinib (Gleevec; STI-571), a targeted competitive inhibitor of the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, revolutionized the clinical treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).1 However, acquired imatinib resistance during the accelerated and blast crisis phases of the disease is an emerging problem and has been linked to gene amplification, to point mutations in Bcr-Abl that impede drug binding or structurally preclude adoption of the inactive conformation, and to loss of p53 function.2,–4 Two novel inhibitors of Bcr-Abl, dasatinib and nilotinib, have been evaluated to address this problem.5,6 Both agents produce clinical responses in many imatinib-refractory patients but not in those carrying the most drug-resistant T315I mutation, which confers cross-resistance to nilotinib and dasatinib.7,8 The lack of effective therapeutic regimens for T315I patients thus highlights the dire need for novel therapeutic strategies that are effective in treating these patients.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors represent a novel class of anticancer agents currently under investigation in preclinical models and in phase 1/2 clinical trials.9,,–12 Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) is an orally bioavailable, well-tolerated pan-HDAC inhibitor with anticancer activity in hematologic and solid malignancies.12,13 SAHA's anticancer effects have been linked to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and to the induction of apoptosis, growth arrest, polyploidy, and autophagy.14,,–17 Whether SAHA's ability to augment autophagy affects its anticancer activity remains unclear. Here we tested the hypotheses that disruption of the autophagy pathway would significantly enhance the anticancer activity of SAHA and that this would prove effective in killing imatinib-resistant CML.

Patients, materials, and methods

Cells and cell culture

Ba/F3 cells and Ba/F3 cells engineered to express comparable levels of wild-type (p210) and mutant forms of Bcr-Abl (E255K, M351T, and T315I) were maintained as previously described.2 K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 media with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. Primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from healthy individuals, and primary human CML cells were obtained from the peripheral blood of imatinib-resistant CML patients under the care of Dr Francis J. Giles at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, after obtaining informed consent in accordance with an approved M. D. Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board (IRB) protocol and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Chemicals and reagents

The following reagents were used: anti-actin antibody, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), chloroquine (CQ), and 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (Sigma, St Louis, MO); anti-active caspase-3, caspase-9, and phospho-Bcr antibodies (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); anti-Abl antibody (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA); anti-p53 and thioredoxin antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); anti–cathepsin D and LAMP-2 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); and Alexa 488– and Alexa 594–tagged secondary antibodies and hydroethidine (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis and cytotoxicity

The following parameters of apoptosis were evaluated using flow cytometry as previously described: propidium iodide/fluorescence-activated cell sorting (PI/FACS) analysis of sub-G0/G1 DNA content, mitochondrial membrane status, and activated caspase-3.15,18 Drug-related effects on cell viability were assessed by MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay as previously described.18

Colony assays

Cells were treated for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations of CQ and SAHA. Drug-treated cells were washed twice in PBS. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were seeded in cytokine-free Methocult methylcellulose medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). Primary murine bone marrow cells were seeded in cytokine-free Methocult supplemented with 20 units/mL recombinant murine IL-3. The cells were incubated for the indicated intervals in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Colonies were stained with 0.5% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) and scored manually.

shRNA knockdown of p53

Bcr-Abl p210- and T315I-expressing Ba/F3 cells were infected with a retrovirus encoding a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence specific for the knockdown of murine p53 or an empty vector control as previously described.4 Infected cells were selected with puromycin, and p53 knockdown was confirmed by immunoblotting.

siRNA transfection

One hundred nM human cathepsin D SMARTpool or siCONTROL siRNA directed at luciferase (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) was transfected into LAMA 84 cells using the Nucleofector II, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). Transfected cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of CQ and SAHA for 48 hours. Drug-induced apoptosis was quantified by PI/FACS and measurement of active caspase-3 as described in “Quantitation of drug-induced apoptosis and cytotoxicity”.

Quantification of intracellular superoxide generation

K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with chloroquine and SAHA for 12 hours. Intracellular superoxide generation was detected by staining cells with hydroethidine (Molecular Probes) as described previously.19 Fluorescence was quantified using a FACSCalibur with CellQuest Pro Software (BD Biosciences).

Confocal microscopy

K562 and LAMA 84 cells were centrifuged at 150g onto glass slides following treatment with chloroquine and SAHA and fixed in methanol, permeabilized, and stained as previously described.18 Images were captured using a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 Meta multiphoton microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with the 1.3 40× objective. Slides were covered with Zeiss Immersol 518F oil during image acquisition. Carl Zeiss Laser Scanning Microscope LSM510 Version 3.2 SP2 software was used for image acquisition.

Immunoblot analyses

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with the assistance of GraphPad Prism software version 4.0a (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) as previously described.18 A P value of less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Disrupting the autophagy pathway enhances the anticancer activity of SAHA against imatinib-resistant cells

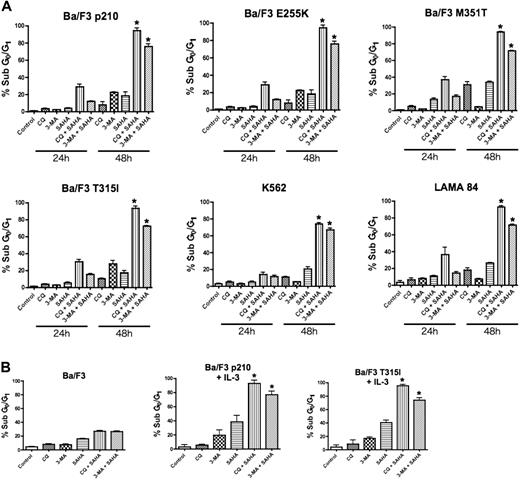

To test the hypothesis that disrupting the autophagy pathway would enhance the proapoptotic effects of the HDAC inhibitor SAHA, Ba/F3 cells engineered to express wild-type (p210) and imatinib-resistant mutant forms (E255K, M351T, and T315I) of Bcr-Abl, and the human Bcr-Abl+ CML cells lines K562 and LAMA 84, were treated with SAHA alone and in combination with two established drugs that target autophagy, chloroquine (CQ) and 3-methyladenine (3-MA).20,21 Drug-induced apoptosis was determined using PI/FACS. A time-dependent induction of apoptosis was observed in all Bcr-Abl–expressing cells and this was especially profound in cells treated with the CQ/SAHA or 3-MA/SAHA combinations (Figure 1A). Notably, Ba/F3 cells expressing the most imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl mutant, T315I, were as sensitive to these combination treatments as cells expressing wild-type Bcr-Abl or the less imatinib-resistant forms of Bcr-Abl (Figure 1A). Furthermore, all Bcr-Abl–expressing cells were significantly more sensitive to the CQ/SAHA or 3-MA/SAHA combinations than Ba/F3 vector control cells, underscoring the known selectivity of SAHA for malignant cells and the potential of these agents when used in combination therapy.13,22 Moreover, selectivity of the p210- or T315I–Bcr-Abl–expressing Ba/F3 cells to the CQ/SAHA or 3-MA/SAHA combinations was not due to differences from culture without interleukin-3 (IL-3), as these cells were also sensitive to these combinations when cultured in the presence of IL-3 (Figure 1B).

Chloroquine or 3-methyladenine selectively augments SAHA-induced apoptosis. (A) Time-dependent induction of DNA fragmentation. Ba/F3 cells engineered to express wild-type (p210) or imatinib-resistant (E255K, M351T, T315I) Bcr-Abl were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 24 or 48 hours. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations also for 24 hours and 48 hours. Percentages of cells with subdiploid DNA were determined by PI/FACS. Results shown represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Targeting autophagy selectively enhances SAHA-induced apoptosis in Bcr-Abl–expressing cells. Ba/F3 vector control cells and Ba/F3 p210 and T315I cells, cultured in the presence of 20 units/mL of IL-3, were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Percentages of apoptotic cells were quantified by PI/FACS. n = 3; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

Chloroquine or 3-methyladenine selectively augments SAHA-induced apoptosis. (A) Time-dependent induction of DNA fragmentation. Ba/F3 cells engineered to express wild-type (p210) or imatinib-resistant (E255K, M351T, T315I) Bcr-Abl were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 24 or 48 hours. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations also for 24 hours and 48 hours. Percentages of cells with subdiploid DNA were determined by PI/FACS. Results shown represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Targeting autophagy selectively enhances SAHA-induced apoptosis in Bcr-Abl–expressing cells. Ba/F3 vector control cells and Ba/F3 p210 and T315I cells, cultured in the presence of 20 units/mL of IL-3, were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Percentages of apoptotic cells were quantified by PI/FACS. n = 3; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

Due to the similar sensitivity of all imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl mutants tested to these combinations, we focused our subsequent analyses regarding the efficacy and mechanism of action of these combinations in p210- and the imatinib-resistant T315I-expressing Ba/F3 cells and the K562 and LAMA 84 human CML cell lines. Importantly, the CML cell lines K562 and LAMA 84 also displayed a time-dependent and marked sensitivity to the CQ/SAHA and 3-MA/SAHA regimens, at least 3-fold over that seen with SAHA alone (Figure 1A).

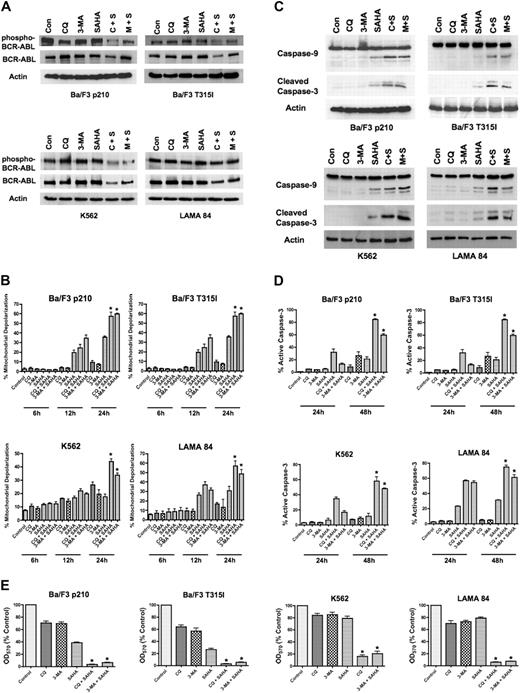

To determine if the inhibition of Bcr-Abl activity contributes to the mechanisms of action of the CQ/SAHA or 3-MA/SAHA regimens, we evaluated their effects on Bcr-Abl autophosphorylation, which is an accurate predictor of Bcr-Abl kinase activity. Immunoblotting analyses demonstrated that treatment of Ba/F3 p210, Ba/F3 T315I, K562 or LAMA 84 cells with CQ, 3-MA, or SAHA alone had no effect on levels of total Bcr-Abl or phospho–Bcr-Abl (Figure A). There were modest decreases in the total and phosphorylated levels of Bcr-Abl protein following treatment of all 4 cell types with the CQ/SAHA regimen, but the effects of the 3-MA/SAHA combination were variable and there were no consistent effects of either of these combinations on the levels of phospho–Bcr-Abl, particularly in K562 and LAMA CML cells (Figure 2A). Therefore, the efficacy of these combination regimens does not directly correlate with significant changes in the activity of Bcr-Abl.

SAHA-induced cell death is augmented by chloroquine or 3-methyladenine. (A) Effects of drug treatments on Bcr-Abl autophosphorylation. p210- and T315I-expressing Ba/F3 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with phospho-Bcr– or c-Abl–specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. C+S indicates CQ plus SAHA; M+S, 3-MA plus SAHA. (B) SAHA-induced mitochondrial depolarization is enhanced by CQ or 3-MA. Ba/F3 p210 and T315I cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 6, 12, and 24 hours. Mitotracker Red CMXRos was used to assess the mitochondrial transmembrane potential status. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments; error bars indicate the SEM. (C) CQ and 3-MA enhance SAHA-induced caspase-9 and -3 activation. Ba/F3 p210- and T315I-expressing cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with caspase-9– and cleaved caspase-3–specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Chloroquine and 3-MA enhance SAHA-induced caspase-3 activation. Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type (p210) or imatinib-resistant (T315I) BCR-ABL were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 24 hours or 48 hours. The percentage of cells containing the active (cleaved) form of caspase-3 was quantified using flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SEM. (E) Effects of CQ, 3-MA, SAHA, and combinations on overall cell growth and viability. Ba/F3 p210 and Ba/F3 T315I cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. n = 3; error bars indicate the SEM. *P < .05.

SAHA-induced cell death is augmented by chloroquine or 3-methyladenine. (A) Effects of drug treatments on Bcr-Abl autophosphorylation. p210- and T315I-expressing Ba/F3 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with phospho-Bcr– or c-Abl–specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. C+S indicates CQ plus SAHA; M+S, 3-MA plus SAHA. (B) SAHA-induced mitochondrial depolarization is enhanced by CQ or 3-MA. Ba/F3 p210 and T315I cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 6, 12, and 24 hours. Mitotracker Red CMXRos was used to assess the mitochondrial transmembrane potential status. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments; error bars indicate the SEM. (C) CQ and 3-MA enhance SAHA-induced caspase-9 and -3 activation. Ba/F3 p210- and T315I-expressing cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with caspase-9– and cleaved caspase-3–specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Chloroquine and 3-MA enhance SAHA-induced caspase-3 activation. Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type (p210) or imatinib-resistant (T315I) BCR-ABL were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, and 1 μM SAHA, and K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 24 hours or 48 hours. The percentage of cells containing the active (cleaved) form of caspase-3 was quantified using flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SEM. (E) Effects of CQ, 3-MA, SAHA, and combinations on overall cell growth and viability. Ba/F3 p210 and Ba/F3 T315I cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 5 mM 3-MA, 2 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. n = 3; error bars indicate the SEM. *P < .05.

To directly assess effects of the combination regimens on apoptosis, we evaluated the kinetics of mitochondrial depolarization (Figure 2B) and also assessed the processing of caspases-9 and -3 to the active forms of these proteases by immunoblotting (Figure 2C). These hallmarks of apoptosis were most pronounced when SAHA was combined with CQ or 3-MA. We further quantified the percentage of cells expressing the active form of caspase-3 following treatment with CQ, 3-MA, SAHA, or the combination of these agents using flow cytometry. Again, the combination of SAHA with either CQ or 3-MA markedly increased the percentage of active caspase-3–positive cells above that achieved with any single agent treatment (Figure 2D). Collectively, these data suggest that SAHA induces apoptosis much more effectively when autophagy is disrupted.

A previous investigation demonstrating that SAHA induces autophagy concluded that the induction of autophagy was an important component of its anticancer mechanism of action.16 Since our data indicated that disrupting the autophagy pathway in combination with SAHA significantly enhanced its proapoptotic effects in imatinib-sensitive and -resistant Bcr-Abl–expressing cells, we next investigated whether this simply shifted the mechanism of cell death from one form to another to enhance cell killing. The effects of SAHA in the presence and absence of CQ and 3-MA on the overall growth and survival of Ba/F3 p210, Ba/F3 T315I, K562, and LAMA 84 cells were assessed using MTT assays. In all cases, the CQ/SAHA and 3-MA/SAHA combinations resulted in marked reductions in cell growth and survival over that observed by SAHA treatment alone (Figure 2E). These data therefore rather suggest that SAHA stimulates autophagy as a cytoprotective mechanism and that inhibiting this process may be an effective strategy to augment the anticancer activity of SAHA.

Since the MTT assay also reflects overall changes in cell growth, we also directly assessed the effects of these agents on the cell-cycle distribution of p210 Bcr-Abl–expressing Ba/F3 cells. While treatment with CQ or 3-MA alone had essentially no effects on cell growth, when used in combination with SAHA these agents markedly increased the percentage of cells with sub-G1/G0 DNA content, which is indicative of apoptosis, and also markedly reduced the percentage of Bcr-Abl–expressing cells in S phase (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figure link at the top of the online article). Therefore, the potential anticancer efficacy of the CQ/SAHA and 3-MA/SAHA regimens is linked to inhibitory effects on both the growth and survival of Bcr-Abl–expressing cells.

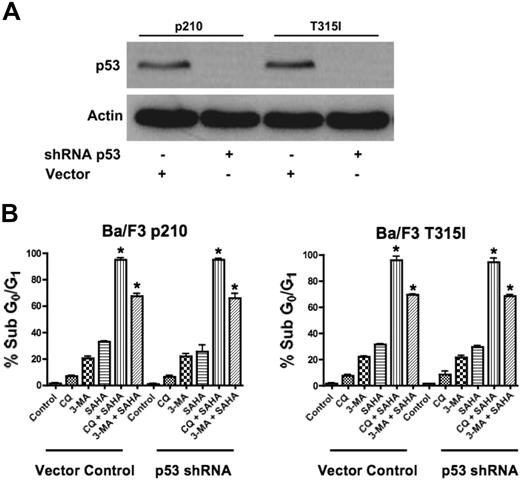

Loss of p53 does not diminish the efficacy of CQ/SAHA or 3-MA/SAHA regimens

Since our data demonstrated that agents that disrupt the autophagy pathway augment the proapoptotic effects of SAHA in the face of Bcr-Abl–mediated imatinib resistance, we tested their potency against other mechanisms of imatinib resistance. In particular, the loss of function of the p53 tumor suppressor is a frequent event in human cancer and is associated with disease progression, increased genetic instability, and drug resistance.23,24 Thus, therapeutic regimens that have activity against p53-deficient or p53-mutated tumors are highly desired and this is also true for CML, where loss of p53 function also contributes to imatinib resistance.4 Given recent studies suggesting mechanistic links between p53 and autophagy, we investigated the efficacy of the SAHA-plus-CQ or–3-MA regimens in the context of impaired p53 function.25 To address this issue, p53 was knocked down using p53-targeted shRNA in p210- and T315I-expressing Ba/F3 cells (Figure 3A).4 Importantly, p53 knockdown did not affect the sensitivity to these combination treatments (Figure 3B). Therefore, this therapeutic strategy may also be effective for the treatment of CML patients having defects in p53.

Functional p53 is not required for chloroquine or 3-methyladenine to synergize with SAHA. (A) shRNA-mediated knockdown of p53 in Ba/F3 p210 and Ba/F3 T315I cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis. Vector control and p53 shRNA-expressing p210 and T315I Ba/F3 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Percentages of apoptotic cells were quantified by PI/FACS. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SEM. *P < .05.

Functional p53 is not required for chloroquine or 3-methyladenine to synergize with SAHA. (A) shRNA-mediated knockdown of p53 in Ba/F3 p210 and Ba/F3 T315I cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis. Vector control and p53 shRNA-expressing p210 and T315I Ba/F3 cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 mM 3-MA, 1 μM SAHA, or the indicated combinations for 48 hours. Percentages of apoptotic cells were quantified by PI/FACS. Bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SEM. *P < .05.

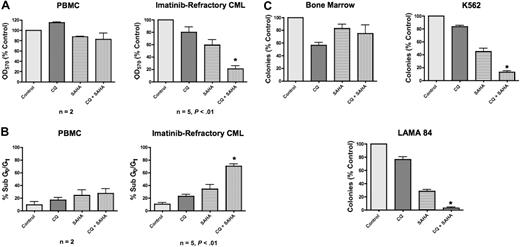

Chloroquine enhances the anticancer activity of SAHA in imatinib-resistant primary CML cells

Both CQ and 3-MA enhance SAHA-induced cell death of imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl–expressing Ba/F3 cells and of the K562 and LAMA 84 CML cell lines. Chloroquine is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved antimalarial agent, whereas 3-MA is unsuitable for in vivo use. To further investigate the potential efficacy of this therapeutic strategy and elucidate its underlying molecular mechanism(s), we therefore focused our subsequent studies on the combination of chloroquine and SAHA due to its potential clinical relevance. To evaluate the efficacy of the CQ/SAHA combination regimen in a clinically relevant scenario, we investigated its effects against primary human CML cells obtained from 5 imatinib-refractory patients including 2 patients in myeloid blast crisis, 1 of whom was positive for the T315I Bcr-Abl mutation, and 3 patients with accelerated myeloid disease. Primary cells were treated with CQ, SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. The effects on the induction of apoptosis and on overall growth and viability following drug treatment were assessed by PI/FACS and MTT assay, respectively. Importantly, the anticancer activity of SAHA against these primary CML cells was significantly enhanced in the presence of CQ (Figure 4A-B). In contrast, peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors treated under the same conditions displayed significantly less induction of apoptosis and loss of viability than primary CML cells, providing further support for the selectivity of this combination (Figure 4A-B). Paralleling our data generated using the Ba/F3 model system of imatinib resistance, the sensitivity of cells from the T315I-positive patient was similar to T315I-negative CML cells. Although additional patient specimens need to be evaluated for a formal statistical analysis, these data provide a promising indication of the potential utility of this regimen in T315I-positive CML patients who fail to respond to conventional therapies.

Chloroquine selectively augments the anticancer activity of SAHA in imatinib-refractory primary CML cells. (A) Effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination on the overall growth and viability of peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors (n = 2) and primary cells from imatinib-refractory patients (n = 5). Cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Effects on overall growth and viability were determined by MTT assays. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis in PBMCs from healthy donors (n = 2) and primary CML cells from imatinib-refractory patients (n = 5). Cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Drug-induced apoptosis was determined by PI/FACS. Error bars indicate the SEM. (C) Prolonged effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination on the clonogenic survival of normal bone marrow versus CML cells. Primary bone marrow cells harvested from C57BL/6J mice and K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, and the combination. Cells were washed twice in PBS and plated in cytokine-free Methocult medium. The Methocult for murine bone marrow cells was supplemented with 20 units/mL IL-3. Colonies from K562 and LAMA 84 cells were scored after 8 days and murine bone marrow colonies were scored after 14 days in culture. n = 2; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

Chloroquine selectively augments the anticancer activity of SAHA in imatinib-refractory primary CML cells. (A) Effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination on the overall growth and viability of peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors (n = 2) and primary cells from imatinib-refractory patients (n = 5). Cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Effects on overall growth and viability were determined by MTT assays. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis in PBMCs from healthy donors (n = 2) and primary CML cells from imatinib-refractory patients (n = 5). Cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Drug-induced apoptosis was determined by PI/FACS. Error bars indicate the SEM. (C) Prolonged effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination on the clonogenic survival of normal bone marrow versus CML cells. Primary bone marrow cells harvested from C57BL/6J mice and K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated for 24 hours with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, and the combination. Cells were washed twice in PBS and plated in cytokine-free Methocult medium. The Methocult for murine bone marrow cells was supplemented with 20 units/mL IL-3. Colonies from K562 and LAMA 84 cells were scored after 8 days and murine bone marrow colonies were scored after 14 days in culture. n = 2; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

SAHA-mediated inhibition of CML clonogenic survival is augmented by chloroquine

To assess the long-term benefit and selectivity of the combination of CQ and SAHA, we investigated its effects on K562, LAMA 84, and primary murine bone marrow cells using colony formation as a readout. K562, LAMA 84, and murine bone marrow cells were treated with CQ, SAHA, or the combination of these drugs for 24 hours, washed twice in PBS, then plated in methylcellulose-containing medium. These assays demonstrated that CQ significantly enhanced the ability of SAHA to inhibit colony formation in both K562 and LAMA 84 cells (Figure 4C). This effect was more pronounced in LAMA 84 cells, where its ability to form colonies was nearly completely abrogated under combination treatment conditions (Figure 4C). Their heightened response is likely due to the fact that LAMA 84 cells are intrinsically more sensitive to SAHA than K562 cells. Notably, the toxicity of this combination against normal murine bone marrow cells was very modest (Figure 4C), again indicating the selectivity of this combination for malignant cells.

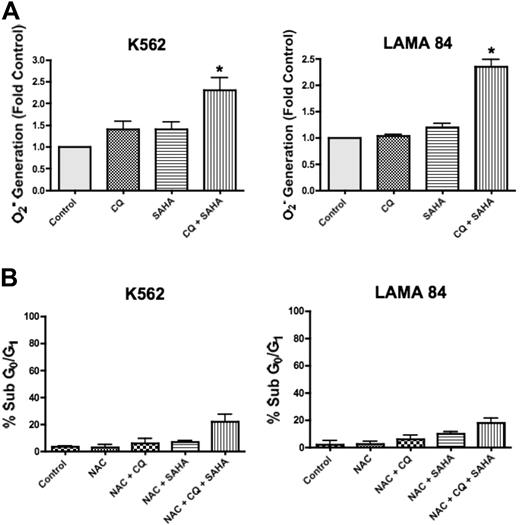

SAHA-induced ROS generation is augmented by chloroquine and plays an important role in cell death

SAHA has pleiotropic effects that contribute to its mechanism of action in malignant cells, including the generation of ROS, and this has been shown to be a critical event in SAHA-induced cell death.17 Interestingly, CQ has also been demonstrated to induce ROS generation in other models.26 To determine whether CQ may modulate SAHA-induced ROS generation, we quantified the intracellular levels of the oxygen radical superoxide (O2−) following a 12-hour treatment with CQ, SAHA, and the combination of CQ and SAHA in K562 and LAMA 84 cells. In both cell lines, there were marked increases in the generation of O2− in cells treated with the combination of CQ and SAHA compared with cells treated with either single agent (Figure 5A). To evaluate whether the enhanced generation of O2− observed in the presence of CQ was an important event underlying its ability to potentiate SAHA-induced cell death, we assayed the ability of the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) to abrogate this effect. K562 and LAMA 84 cells pretreated with NAC displayed significantly reduced apoptosis induction in response to CQ and SAHA (Figure 5B compared with Figure 1A). Therefore, the generation of ROS plays an important role in the induction of cell death by the combination of CQ and SAHA.

Chloroquine augments SAHA-induced superoxide generation, which mediates cell death. (A) Quantification of cellular superoxide generation. K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 12 hours. Superoxide production was determined by hydroethidine staining in conjunction with flow cytometry as described in Quantitation of intracellular superoxide generation in P‘Patients, materials, and methods.” n = 3; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05. (B) Effects of NAC on drug-induced cell death. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC for 3 hours. Following pretreatment with NAC, cells were exposed to 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Drug-induced apoptosis was quantified by PI/FACS. n = 3; error bars represent the SEM.

Chloroquine augments SAHA-induced superoxide generation, which mediates cell death. (A) Quantification of cellular superoxide generation. K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 12 hours. Superoxide production was determined by hydroethidine staining in conjunction with flow cytometry as described in Quantitation of intracellular superoxide generation in P‘Patients, materials, and methods.” n = 3; error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05. (B) Effects of NAC on drug-induced cell death. K562 and LAMA 84 cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC for 3 hours. Following pretreatment with NAC, cells were exposed to 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 48 hours. Drug-induced apoptosis was quantified by PI/FACS. n = 3; error bars represent the SEM.

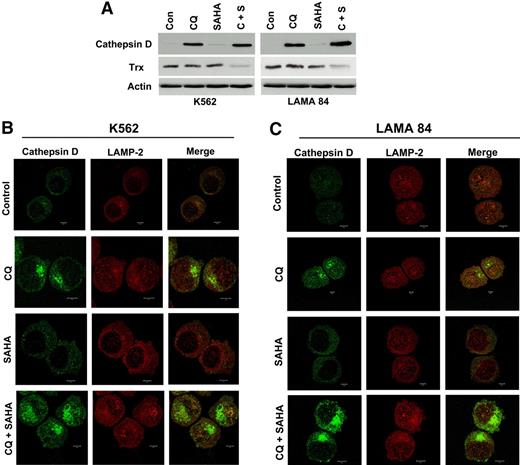

Chloroquine and SAHA modulate the expression and subcellular localization of cathepsin D and reduce the levels of its substrate thioredoxin

Chloroquine is a lysosomotropic agent that has been suggested to inhibit autophagy by perturbing lysosomal function.20,21 We next investigated how the lysosomal-related effects of CQ may contribute to its ability to potentiate the anticancer activity of SAHA. Lysosomes contain a number of proteases that participate in the autophagic degradation of many intracellular proteins. The majority of these proteases have strict acidic pH requirements for their activity, yet a few members of the cathepsin family retain activity under physiologic conditions.27 In particular, the aspartic protease cathepsin D has been shown to function at physiologic pH.28 Moreover, cathepsin D can be stimulated by oxidative stress and has been suggested to be involved in the mechanism of action of several anticancer agents, including resveratrol, doxorubicin, and etoposide.29,30

We first investigated the potential effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination of these agents on cathepsin D expression by immunoblotting. The basal levels of cathepsin D in K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were extremely low. Remarkably, treatment with CQ led to a dramatic increase in cathepsin D levels, whereas SAHA treatment stimulated only very modest increases in the steady-state levels of cathepsin D (Figure 6A). The combination of CQ and SAHA resulted in further increases in cathepsin D levels over single-agent treatments in both CML cell lines, especially in LAMA 84 cells (Figure 6A), which are more sensitive to SAHA- and CQ/SAHA-induced cell death.

Chloroquine and SAHA increase the expression and alter the subcellular localization of cathepsin D and reduce the levels of its substrate thioredoxin (Trx). (A) Drug-induced modulation of cathepsin-D and Trx expression. K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Immunoblotting was used to evaluate cathepsin-D and Trx expression. Actin was used as a loading control. (B-C) Subcellular localization of cathepsin D. K562 (B) and LAMA 84 (C) cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 18 hours. Cells were centrifuged at 150g onto glass slides and stained with anti–cathepsin-D and anti–LAMP-2 (lysosomal marker) antibodies as described in Confocal Microscopy in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. Magnification, × 40.

Chloroquine and SAHA increase the expression and alter the subcellular localization of cathepsin D and reduce the levels of its substrate thioredoxin (Trx). (A) Drug-induced modulation of cathepsin-D and Trx expression. K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Immunoblotting was used to evaluate cathepsin-D and Trx expression. Actin was used as a loading control. (B-C) Subcellular localization of cathepsin D. K562 (B) and LAMA 84 (C) cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 18 hours. Cells were centrifuged at 150g onto glass slides and stained with anti–cathepsin-D and anti–LAMP-2 (lysosomal marker) antibodies as described in Confocal Microscopy in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. Magnification, × 40.

To explore the possible functional significance of increases in cathepsin D expression and how it may relate to the increased levels of ROS we observed in cells treated with these agents, we assessed the effects of these agents on the expression of the antioxidant protein thioredoxin (Trx). Trx is a known substrate for proteolytic degradation by cathepsin D and is overexpressed in many types of cancer, where it has been linked to drug resistance due to its ability to inhibit apoptosis.31,–33 Importantly, Trx expression is induced in normal, but not transformed, cells upon treatment with SAHA, and these selective effects on Trx expression have been proposed to be a critical factor underlying SAHA's preferential killing of malignant cells.22,34 We therefore evaluated the effects of CQ, SAHA, and the combination of these drugs on Trx expression. Immunoblotting analysis revealed only very modest effects of single-agent treatments on Trx expression in K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells. In sharp contrast, the combination of CQ and SAHA caused a marked reduction in Trx levels in both of these CML cell lines (Figure 6A). Given the pivotal role of Trx in SAHA-induced cell death and its links to both oxidative stress and cathepsin D, modulation of Trx expression may thus be an important component of the mechanism underlying CQ's ability to potentiate the anticancer effects of SAHA.

Certain chemotherapeutic agents stimulate lysosomal membrane permeability (LMP) and the relocalization of cathepsin D from the lysosomes into the cytosol where it appears to play an important role in apoptosis.29,35,–37 To address the effects of these agents on cathepsin D localization, we used fluorescent confocal microscopy. As expected based on our immunoblotting analyses, cathepsin D staining was very weak in K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells and appeared to be predominantly lysosomal. SAHA treatment led to a modest increase in cathepsin D fluorescence that appeared to be cytosolic in its localization and punctate in its distribution. In contrast, cells treated with CQ showed a dramatic increase in cathepsin D staining, which appeared to by largely cytosolic, nonlysosomal, and organized into large aggregates. This effect was more pronounced in cells treated with the combination of CQ and SAHA, suggesting that, like CQ, SAHA may play a role in promoting cathepsin D aggregation (Figure 6B-C).

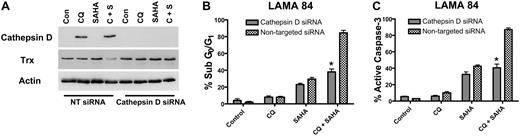

Cathepsin D is an important mediator of the anticancer activity of the chloroquine/SAHA combination

To determine whether the marked increases in cathepsin D expression by the CQ/SAHA regimen played a critical role in promoting the anticancer activity of this combination, we knocked-down cathepsin D expression using siRNA. Cathepsin D–targeted siRNA abolished the induction of cathepsin D by CQ and the combination of CQ and SAHA in LAMA 84 cells (Figure 7A). Moreover, LAMA 84 cells transfected with cathepsin D siRNA were significantly less sensitive to the combination of CQ and SAHA than those transfected with a nontargeted control siRNA (Figure 7B-C). Finally, the reduced sensitivity of LAMA 84 cells to these agents may be due, at least in part, to the inability of the combination to reduce thioredoxin expression in the presence of cathepsin D siRNA (Figure 7A). These data provide additional evidence that cathepsin D indeed mediates the decrease in Trx expression stimulated by the combination of CQ and SAHA. Importantly these findings also establish a critical role for cathepsin D as a mediator of the anticancer effects of the CQ/SAHA combination regimen.

Knockdown of cathepsin D diminishes the potency of the chloroquine-SAHA combination and restores Trx expression. (A) siRNA knockdown of cathepsin D. Cathepsin-D–targeted or nontargeted siCONTROL siRNA were transfected into LAMA 84 CML cells using the Nucleofector II. Transfected cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Immunoblotting was used to evaluate the efficiency of cathepsin D knockdown. Actin served as a loading control. (B-C) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis. LAMA 84 CML cells transfected with cathepsin D–targeted or siCONTROL siRNA were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Apoptosis was quantified by PI/FACS (B) and active caspase-3 staining (C). n = 3, error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

Knockdown of cathepsin D diminishes the potency of the chloroquine-SAHA combination and restores Trx expression. (A) siRNA knockdown of cathepsin D. Cathepsin-D–targeted or nontargeted siCONTROL siRNA were transfected into LAMA 84 CML cells using the Nucleofector II. Transfected cells were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Immunoblotting was used to evaluate the efficiency of cathepsin D knockdown. Actin served as a loading control. (B-C) Quantification of drug-induced apoptosis. LAMA 84 CML cells transfected with cathepsin D–targeted or siCONTROL siRNA were treated with 25 μM CQ, 2 μM SAHA, or the combination for 24 hours. Apoptosis was quantified by PI/FACS (B) and active caspase-3 staining (C). n = 3, error bars represent the SEM. *P < .05.

Discussion

Drug resistance continues to be a major obstacle that limits the rate of successful outcomes for cancer patients, irrespective of tumor type, and thus the identification and validation of novel therapeutic strategies for chemorefractory disease represents a significant challenge in cancer research. We hypothesized that targeting the autophagy pathway might enhance the anticancer activity of SAHA, and the studies presented herein demonstrate that agents such as CQ or 3-MA synergistically potentiate the proapoptotic effects of SAHA. Moreover, Ba/F3 cells expressing even the most imatinib-resistant T315I Bcr-Abl mutant or the partially imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl mutants (E255K, M351T) were as sensitive to the combination of 3-MA or CQ and SAHA as those expressing wild-type p210. More importantly, primary cells from CML patients who are clinically refractory to imatinib also displayed a marked sensitivity to the combination of these agents. Our analyses showed that targeting the autophagy pathway not only increases the ability of SAHA to induce apoptosis but also results in a significant reduction in CML cell clonogenic survival. These data therefore demonstrate the potential long-term therapeutic benefits of such a strategy. Finally, these combinations appear to be very selective for malignant cells and are effective even when p53 function is impaired. Since p53 defects are a major contributing factor in drug resistance and have been recently linked to reduced imatinib sensitivity, our results may have very important clinical implications.4,23,24 A recent report suggests that p53 itself may be an important regulator of the autophagy pathway, where damage-regulated autophagy modulator (DRAM), a lysosomal protein and p53 transcription target, appears to be required for p53-induced autophagosome formation and for p53-dependent apoptosis.25,38 Nonetheless, our findings that agents that disrupt the autophagy pathway still potentiate the anticancer activity of SAHA in a p53-null context underscore their utility in treating CML resistance that is due to alterations in p53 and suggest that they may be applied to other cancers where loss of function of p53 contributes to therapeutic resistance.

The ability of CQ to potentiate the anticancer activity of SAHA appears to be intimately linked to ROS generation. Grant and colleagues (Yu et al,17 Rosato et al,39,40 Dai et al41 ) have established that increased ROS generation plays a critical role in the cell death induced by SAHA and other HDAC inhibitors, and CQ has also been reported to alter cellular redox status.26 We observed a modest, but significant, increase in cellular superoxide generation upon treatment with CQ alone. However, the combination of CQ with SAHA resulted in a marked increase in superoxide generation over what could be achieved by either single agent. Further, elevated ROS generation appears to be required for maximal cell death by these agents, since treatment with the antioxidant NAC dramatically reduced their efficacy. Interestingly, several studies have suggested that disruption of the cellular redox status is an important component of the mechanism underlying the synergy between HDAC inhibitors and other anticancer agents.42,,–45

To explore the molecular mechanism(s) linking increased superoxide generation stimulated by the combination of these drugs to enhanced anticancer activity, we focused our investigation on 2 key proteins, thioredoxin (Trx) and cathepsin D. The antioxidant protein Trx is one of the most important regulators of cellular redox status. Not surprisingly, Trx is overexpressed in many types of cancer due to intrinsic oxidative stress and has antiapoptotic properties that contribute to drug resistance.31,–33 Furthermore, Trx expression and activity are specifically and selectively induced in normal, but not malignant, cells in response to SAHA treatment.22 Indeed, this differential effect on Trx expression has been proposed as a key factor involved in SAHA's therapeutic selectivity, as increasing levels of Trx in malignant cells reduces their sensitivity to SAHA, whereas knockdown of Trx with siRNA enhances the anticancer activity of SAHA.22 Our data demonstrated minimal effects of single-agent treatments on Trx expression. In contrast, treatment of K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells with the combination of CQ and SAHA led to a dramatic reduction in Trx levels. This down-regulation of the antioxidant Trx likely contributes to the synergistic increases in ROS generation we observed in CML cells treated with the combination of CQ and SAHA, which promotes ROS-mediated cell death. However, events occurring upstream of Trx also likely contribute to the increased ROS generation stimulated by these agents. In particular, mitochondria are the primary intracellular source of superoxide generation, and thus drug-induced disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis, such as we have observed with the combination of CQ and SAHA, may also play a significant role in ROS generation and cell death.46

Agents that disrupt the permeability of lysosomal membranes have been shown to activate p53-independent apoptosis.47 Since the ability of CQ to augment SAHA's anticancer activity was associated with reductions in Trx expression, we reasoned that CQ might disrupt the normal regulation and/or localization of cathepsin D, a lysosomal aspartic protease that specifically targets Trx for degradation and that has been reported to play an active role in chemotherapy-induced apoptosis following its translocation from the lysosomes to the cytosol.29,30 Several studies have demonstrated that cathepsin D retains its activity at physiologic pH and, notably, that it has proapoptotic effects.27,,–30,37 These unique properties distinguish cathepsin D from the majority of lysosomal proteases, which require the acidic pH environment of lysosomes for their activity. Indeed, our data demonstrate that CQ treatment leads to dramatic increases in the levels of cathepsin D in K562 and LAMA 84 CML cells and that this response is further enhanced by SAHA. The ability of CQ to promote increased cathepsin D expression has also been noted in an earlier investigation, yet our knockdown studies in LAMA 84 CML cells now establish that cathepsin D plays an essential role in the ability of CQ to potentiate the proapoptotic effects of SAHA and to degrade the cathepsin D substrate Trx.48 Based on our studies, it also appears that drug-induced modulation of cathepsin D expression underlies the increased activation of caspase-3 observed under combination conditions, since apoptosis induced by the CQ/SAHA combination is impaired by knockdown of cathepsin D.

Equally striking are the effects of CQ and the CQ/SAHA combination on the subcellular localization of cathepsin D. Specifically, CQ treatment leads to a marked accumulation of cathepsin D into large aggregates that are not colocalized with lysosomes. Further, this response is augmented by SAHA, which as a single agent has limited effects on cathepsin D expression or localization. Interestingly, these large aggregates of cathepsin D bear a striking resemblance to “aggresome” structures of ubiquitin-conjugated proteins that form in malignant cells in response to treatment with proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib.15 However, apart from its link to Trx degradation and caspase-3 activation, it is unclear how aggregates of cathepsin D would promote the anticancer activity of HDAC inhibitors. In particular, in contrast to ubiquitin-conjugated aggresomes that appear to have cytoprotective functions, the formation of cathepsin D aggregates appears to be directly correlated with the ability of CQ to enhance SAHA-induced cell death. Another feature that distinguishes cathepsin D aggregates from aggresomes induced by proteasome inhibitors is their differing dependence upon HDAC6 function for their formation. Specifically, recent studies have shown that HDAC6 inhibition disrupts proteasome inhibitor–induced aggresomes and synergistically enhances drug-induced apoptosis.15,49 This is clearly not the case with the aggregates of cathepsin D, which continue to form in the presence of SAHA, which inhibits HDAC6 activity. We are currently investigating the mechanistic differences between the disruption of autophagic versus proteasomal protein degradation and how these processes can be differentially modulated by HDAC inhibitors for therapeutic benefit (S.T.N., J.S.C., D.J. McConkey, J.L.C., and J.A.H., manuscript in preparation).

Chloroquine is an FDA-approved antimalarial agent and the data presented herein suggest that chloroquine may have utility in combination with SAHA in future clinical trials of imatinib-resistant advanced CML. We would propose that other venues for study of this combination are also warranted, particularly regarding its potential efficacy as a therapeutic strategy for chronic-phase CML. Based on our findings, we propose a model in which CQ-mediated effects on cathepsin D may promote SAHA's ability to degrade Trx, which in turn provokes increases in ROS generation, caspase activation, and potentiation of SAHA's anticancer activity. Since SAHA appears to have broad-spectrum anticancer activity, this combination regimen should also be explored in other cancer models, and we are currently pursuing such studies (S.T.N., J.S.C., D.J. McConkey, J.L.C., and J.A.H., manuscript in preparation). It will also be interesting to investigate whether other known or novel pharmacologic inhibitors of autophagy can enhance the anticancer activity of SAHA. Collectively, our results demonstrate that targeting the autophagy pathway is a promising therapeutic strategy to enhance SAHA-induced apoptosis, and they provide a platform for future studies to explore this combination for the treatment of chemorefractory disease.

The online version of this manuscript contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Charles L. Sawyers (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for providing Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type and mutant forms of Bcr-Abl and for his critical reading of the manuscript; Dr Scott W. Lowe (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) for his generous gift of murine p53 shRNA and empty vector constructs; Dr Michael Kastan (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for stimulating discussions on the use of chloroquine in therapeutics; and Min Du for her assistance in obtaining peripheral blood from healthy donors.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA76379 (J.L.C.), Cancer Center Core Grant CA21765, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

J.S.C. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship grant from The American Cancer Society.

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Authorship

Contribution: J.S.C. wrote the manuscript and was involved in all aspects of the study including experimental design, performing research, and data analysis; S.T.N. provided intellectual input regarding experimental design and data interpretation, performed research, and was involved in the preparation of the manuscript; C.N.K., H.Z., C.Y., and L.C. performed research and contributed to data analysis; J.A.H. and P.H. provided intellectual input regarding experimental design and data interpretation; F.J.G. was involved in patient selection, obtained informed consent from CML patients, and participated in experimental design and data analysis/interpretation; and J.L.C. directed the study and was involved in all aspects of experimental design, data analysis/interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: John L. Cleveland, Department of Cancer Biology, The Scripps Research Institute-Florida, 5353 Parkside Dr, Jupiter, FL 33458; e-mail: jcleve@scripps.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal