Abstract

Mutations in ELA2 encoding the neutrophil granule protease, neutrophil elastase (NE), are the major cause of the 2 main forms of hereditary neutropenia, cyclic neutropenia and severe congenital neutropenia (SCN). Genetic evaluation of other forms of neutropenia in humans and model organisms has helped to illuminate the role of NE. A canine form of cyclic neutropenia corresponds to human Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 2 (HPS2) and results from mutations in AP3B1 encoding a subunit of a complex involved in the subcellular trafficking of vesicular cargo proteins (among which NE appears to be one). Rare cases of SCN are attributable to mutations in the transcriptional repressor Gfi1 (among whose regulatory targets also include ELA2). The ultimate biochemical consequences of the mutations are not yet known, however. Gene targeting of ELA2 has thus far failed to recapitulate neutropenia in mice. The cycling phenomenon and origins of leukemic transformation in SCN remain puzzling. Nevertheless, mutations in all 3 genes are capable of causing the mislocalization of NE and may also induce the unfolded protein response, suggesting that there might a convergent pathogenic mechanism focusing on NE.

Neutrophils and monocytes

Neutrophils (also known as “polymorphonuclear leukocytes” and “granulocytes”) are terminally differentiated cellular components of the innate immune system that constitute about 35% to 75% of the population of peripheral leukocytes.1 They kill bacterial and fungal pathogens through phagocytosis and are armed with an arsenal of proteases, antimicrobial peptides, and reactive oxygen species.2 They also participate in the inflammatory response and produce cytokines, eicosanoids, and other signaling molecules.3 Monocytes, constituting about 5% to 10% of peripheral leukocytes, are the circulating progenitors of tissue macrophages and dendritic cells and arise in the bone marrow from common myeloid progenitors shared with neutrophils.4

“Neutropenia” refers to a deficiency in numbers of neutrophils. The normal neutrophil count fluctuates and varies across human populations and within individuals in response to stress and infection but typically well exceeds 1500/μL5, and neutropenia is usually categorized as severe when the cell count is below 500/μL. Common causes of neutropenia include cancer chemotherapy, autoimmune diseases, drug reactions, and hereditary disorders.6 Among the latter, neutropenia may occur as one component of a number of inherited syndromes diversely featuring morphologic abnormalities of neutrophils, immunodeficiency, involvement of other lineages or pancytopenia, metabolic abnormalities, and systemic findings. This review, however, focuses on the 2 primary genetic forms of neutropenia: cyclic neutropenia (also known as “cyclic hematopoiesis”) and the Kostmann syndrome of infantile agranulocytosis, more commonly referred to as “severe congenital neutropenia” (SCN), where mutations of the ELA2 gene, encoding the neutrophil granule serine protease, neutrophil elastase (NE), have proved to be the nearly exclusive or most common cause, respectively.

Cyclic neutropenia

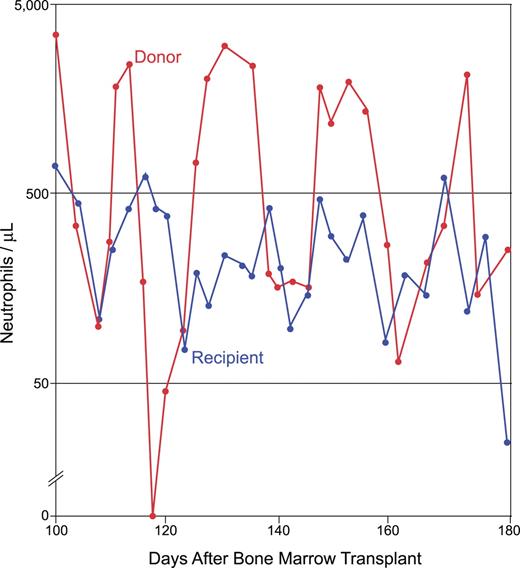

In cyclic neutropenia, the peripheral-blood neutrophil and monocyte counts oscillate in opposite phase to one another with an average 21-day frequency.6 Peak neutrophil counts tend toward somewhat subnormal values, although they can also be in the normal range. Infections, including aphthous stomatitis, periodontitis, and typhlitis, can arise during the nadir of the cycle, when the neutrophil count drops below 500/μL and approaches zero. The infectious flora may differ from what is encountered with acquired neutropenia, suggesting a functional deficiency in neutrophils extending beyond that of low numbers. Cyclic neutropenia is transmitted by autosomal dominant genetics but, as with other often lethal dominant disorders, sporadic cases commonly arise from new germ line mutations. In a remarkable anecdote, a girl with the disease served as a hematopoietic stem cell donor for her sister, who did not have cyclic neutropenia but who was rather suffering from acute lymphoblastic leukemia ; the bone marrow transplantation cured the sibling of leukemia, but it transferred cyclic hematopoiesis to her, and the 2 sisters' neutrophil counts began to cycle more or less synchronously from that point in time forward (Figure 1).

Cyclic neutropenia transferred from an affected sibling to her unaffected sister by bone marrow transplantation. The donor and recipient cycle nearly synchronously. The family is pedigree number 601 from Horwitz et al,43 which segregates the ELA2 +5 G>A mutation in intron 4. The unaffected sister (who lacked the family's ELA2 mutation) underwent bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; her affected sister (later found to have an ELA2 mutation) was HLA matched and served as the donor. Adapted from Krance et al with permission.

Cyclic neutropenia transferred from an affected sibling to her unaffected sister by bone marrow transplantation. The donor and recipient cycle nearly synchronously. The family is pedigree number 601 from Horwitz et al,43 which segregates the ELA2 +5 G>A mutation in intron 4. The unaffected sister (who lacked the family's ELA2 mutation) underwent bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia; her affected sister (later found to have an ELA2 mutation) was HLA matched and served as the donor. Adapted from Krance et al with permission.

Most patients are responsive to recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF),8 the primary endogenous neutrophil growth factor, at doses of 2 to 3 μg/kg at 1- or 2-day intervals. G-CSF does not abrogate cycling but tends to shorten the cycle length and increases the amplitude of the waves, thereby reducing the duration of the neutropenic nadir.

Some9,10 have reported that the population of bone marrow progenitor cells, as measured by in vitro colony formation assays, varies in concert with the peripheral neutrophil count. Other studies11,12 failed to observe that myeloid progenitor populations in the bone marrow fluctuate over the course of the cycle but found that they did demonstrate a persistently sluggish proliferative response to cytokines. The discrepancies may reflect the different culture methods used in these studies.

Kostmann syndrome of SCN

Kostmann first described noncyclic, congenital agranulocytosis13 among a consanguineous cohort in northern Sweden. In distinction to cyclic neutropenia, it characteristically demonstrates promyelocytic maturation arrest in the bone marrow. The monocyte count is elevated in SCN, suggesting that, just as with cyclic neutropenia, there is a reciprocal relationship between the production of these 2 types of cells, which represent the alternate fates available to the committed myeloid progenitor cell. The original cohort of patients lived in isolated areas of Sweden, where people are perhaps more likely to be interrelated through a small founding population and where Kostmann syndrome is transmitted with autosomal recessive inheritance. However, most cases of SCN arise sporadically, consistent with its transmission as an often lethal, autosomal dominant disorder. Rare, sex-linked recessive inheritance also occurs, now recognized to be the result of activating mutations in WAS, a gene in which different sorts of mutations are more commonly responsible for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome of thrombocytopenia.14,15 SCN usually, though not always, responds to G-CSF therapy but at doses higher than those used to treat cyclic hematopoiesis.16 The introduction of G-CSF therapy has improved survival, but even treated patients continue to succumb to infectious complications at a rate of 0.9% per year.17 But, with reduced morbidity from infection, myelodysplasia (MDS) and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) have emerged as significant complications, occurring in 13% of all SCN patients.17,18 The only curative therapy is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

G-CSF is suspected to be a risk factor for developing MDS or AML in SCN,17–20 because the frequency of MDS or AML increases with the dose and duration of G-CSF treatment and because at least one case of AML has occurred in SCN in which the blast count rose and fell directly in response to G-CSF dosing.21 Among SCN patients requiring more than 8 μg/kg/d G-CSF, the incidence of MDS or AML was 40% after 10 years.17 Of course, it could be that those with the most severe forms of the disease face the greatest risk of malignant evolution and are unresponsive to all but the largest doses of the cytokine. Leukemic transformation in the era before G-CSF therapy is also documented. On the other hand, G-CSF use in patients undergoing chemotherapy for solid tumors is implicated in treatment-related leukemia.22

On electron microscopy, at least some SCN patients demonstrate ultrastructural abnormalities of granule formation in myeloid precursor cells obtained from the bone marrow.23 In accord with these observations, myeloid precursor cells from SCN patients demonstrate reduced abundance of some granule proteins24 or the transcripts11,25 that encode them—not the least of which is, in fact, NE.25 Interestingly, the deficiency of granule proteins persists in the neutrophils obtained from SCN patients who have therapeutically responded to G-CSF (R. Badolato, personal communication, May 2006). In most11,26,27 but not all28 studies of in vitro colony formation potential, bone marrow obtained from SCN patients demonstrates a reduction in the number of granulocyte-macrophage colonies and a poor responsiveness to G-CSF.27 The lack of consistency among such studies, performed before genes causing SCN became known, is not surprising in light of the genetic and possible mechanistic heterogeneity of the disorder.

The greatest clues into molecular mechanism have been the result of advances in the understanding of the mendelian and somatic genetics of the disorder.

G-CSF receptor gene (G-CSFR) mutations in SCN

The role of mutations of the G-CSF receptor gene (G-CSFR) encoding the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor has remained bewildering. G-CSFR is an obvious gene of interest for hereditary neutropenia, and mutations were initially reported in 2 individuals with SCN who developed AML,29 but whether these were somatic or constitutional in origin remained ambiguous. It later emerged that G-CSFR mutations represent acquired, nonheritable events in the bone marrow, typically accumulating as SCN progresses to MDS and AML, and are thus not genetically causative of SCN.30–32 The mutations are usually but not always present in MDS or AML, and they may also be present in the absence of malignancy.33,34 Subsequently, there have been 2 reports35,36 of sporadic SCN in patients with heterozygous G-CSFR mutations appearing in both the bone marrow and buccal cells, suggesting that G-CSFR mutations can arise de novo constitutionally. (Buccal swabs can become contaminated with neutrophils,37 and it is somewhat difficult to understand how these mutations can cause neutropenia when, as discussed in the next paragraph, they are felt to be compensatory and possibly neutrophilic in their effects.)

The G-CSF receptor is a member of the hematopoietin superfamily.38 Upon ligand binding, it activates proliferative signaling through Jak/STAT pathways.39 G-CSFR mutations are most often chain-terminating C>T transitions at one of several CAG codons.34 They delete a portion of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor that contains a “SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling) box.” Normally, SOCS3 interacts with the G-CSF receptor via the SOCS box to subsequently inhibit downstream signaling by STAT5. The mutations consequently prevent SOCS3-mediated inhibition of STAT5 and result in a hyperproliferative response to G-CSF.40 It is possible that myeloid progenitor cells containing G-CSFR mutations have a selective growth advantage in the hypoproliferative bone marrow environment of SCN patients and that this may represent a first step toward turning the bone marrow leukemic.34,38 Somatic mutations seen with leukemia outside of this setting are also at times present with malignant transformation in SCN and include monosomy 7,41 trisomy 21,42 and activating ras mutations.41

Mutations in ELA2, encoding NE, in cyclic neutropenia and SCN

To identify the gene responsible for cyclic neutropenia, we performed a genomewide screen for genetic linkage in 13 families with a multigenerational history of cyclic neutropenia and mapped the locus to the terminus of the short arm of chromosome 19, where a positional cloning strategy identified 7 different heterozygous mutations in ELA2, encoding NE, which perfectly segregated with disease in each family, as well as a new constitutional mutation arising in a sporadic case in which both parents were unaffected and lacked the mutation.43

Subsequently, we evaluated ELA2 as a candidate gene in 27 unrelated SCN patients and found 15 different heterozygous ELA2 mutations in 21 (78%) of the patients. The mutations segregated with disease in families in which there were multiple affected individuals, indicating that, unlike G-CSFR mutations, which are always or nearly always somatic, ELA2 mutations are constitutional. The causative role of ELA2 mutations in congenital neutropenia has been repeatedly confirmed, and hundreds of patients with mutations are now known.11,25,44–46 Genetic testing has become commercially available and is clinically useful in differentiating acquired from hereditary neutropenia, gauging urgency for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, offering genetic counseling, and in prenatal and preimplantation diagnosis.6

Subsequent reports indicate that ELA2 mutations are present in 35%44 to 69%45 of SCN cases. Our initial results probably overestimated the frequency of ELA2 mutations in SCN, because they came from a severely affected population of patients, and it now appears that ELA2 mutations define a subset of patients with more severe disease44 : those with lower neutrophil counts, less of a therapeutic response to G-CSF, and most vulnerability to MDS or AML. In fact, most cases of leukemia in SCN in which ELA2 mutational status is known have occurred in those in whom the disease is the result of an ELA2 mutation.44,47

Ironically, the genetic etiology of Kostmann's original patients remains unsolved. One of 4 recently studied people with SCN who are descended from the pedigrees evaluated by Kostmann was found to have a de novo heterozygous ELA2 mutation,48 but ELA2 mutations cannot account for neutropenia in the other 3 individuals, presumably because they harbor mutations in a different gene.

Biochemical properties of NE

NE is a monomeric, approximately 30-kDa glycoprotein.49 Its catalytic site contains a charge relay triad composed of the amino acids His, Asp, and Ser. Its major inhibitor is the serpin α-1-antitrypsin, which forms an irreversible complex upon binding and cleavage by NE.50 Although NE is a broad-specificity protease, the prototypical substrate from which it takes its name is elastin, and inherited deficiency of α-1-antitrypsin leads to pulmonary emphysema,51 at least in part through excessive degradation of elastic tissue by NE released from neutrophils migrating to the lung in response to inflammatory stimuli. NE is most closely related to 2 other neutrophil granule proteins, proteinase 3 and azurocidin.52 Proteinase 353 is the most frequent target antigen of cANCAs in Wegener granulomatosis. Azurocidin has evolutionarily lost its catalytic serine and functions as an antimicrobial peptide.54 The genes for all 3 lie in a coordinately regulated55 cluster on chromosome 19p13.3. ELA2 is specifically transcribed in promyelocytes and promonocytes in the bone marrow, but the protein, if not its transcript, persists in cells through terminal differentiation into neutrophils and monocytes.56 The 267 amino acids of NE include a 27-residue “pre” sequence cleaved by signal peptidase, a 2-reside “pro” sequence removed57 by the cysteine protease DPPI, and a dispensable (with respect to proteolytic activity58 ) 20-residue carboxyl terminus processed by an unknown protease. Isoforms of NE both with and without the carboxyl terminus are abundant in neutrophils. NE primarily localizes to azurophilic neutrophil granules, but it also resides extracellularly, is located on the cell surface and intracellular membranes,59 and has been found in the nucleus.60

Genotype-phenotype correlation of ELA2 mutations

At least 45 different ELA2 mutations (Figure 2) are now known, but the association between a particular ELA2 mutation and the clinical form of neutropenia (cyclic neutropenia versus SCN) is imperfect, because many of the same mutations appear in either disorder.44,47 One potential explanation for the lack of strict correlation may be that the clinical distinction between cyclic neutropenia and SCN can be difficult. Not only are serial blood counts necessary to observe cycling, but the cycling phenomenon may appear intermittently throughout the natural history of cyclic neutropenia or may initiate in some SCN patients in response to G-CSF treatment.47 Nevertheless, some generalizations regarding genotype-phenotype correlation of ELA2 mutations in hereditary neutropenia hold true. First, in our experience (unpublished, July 1999 to present) the most common sort of mutations causing cyclic hematopoiesis are single base substitutions occurring at 1 of 3 different positions in intron 4 (+1 G>A, +3 A>T, or +5 G>A, with the first of these accounting for most), each of which similarly disrupts the normal splice donor site at the end of the fourth exon and forces use of a cryptic, upstream splice acceptor site, thereby causing the internal in-frame deletion of 30 nucleotides from the transcript and 10 amino acid residues (ΔV161-F170) from the protein.43 These mutations are seldom encountered in SCN. Second, many of the mutations responsible for SCN are chain-terminating, nonsense, or frame-shift events in the fifth (and final) exon. Because mutations in the last exon should not be subject to nonsense-mediated decay,61 they are expected to yield a stable transcript resulting in translation of a shortened protein. The absence of chain-terminating mutations in anything but the final exon, where they would be expected to consequently act as null alleles, indicates a dominant-negative or gain-of-function mechanism and eliminates haploinsufficiency. Chain-terminating mutations in the last or any other exon are not observed in cyclic hematopoiesis. Third, the ELA2 mutation G185R seems particularly severe,6,44 and it appears that the several patients with G185R have SCN with an absolute neutrophil count close to zero, are unresponsive to G-CSF therapy, and usually develop MDS or AML.

Correlation of mutations in ELA2, encoding NE, with cyclic neutropenia or SCN. There are 2 categories of mutations: those reported exclusively in SCN (blue, below the gene structure) or those reported predominantly in cyclic neutropenia (but that also may have been described in SCN; pink, above the line). *, amino acid substitutions; ▾, deletions (or nonsense mutations); ▴, an insertion. Exon 4 deletions are in frame, and the cluster of exon 5 deletions are all frame-shift, chain-terminating events.

Correlation of mutations in ELA2, encoding NE, with cyclic neutropenia or SCN. There are 2 categories of mutations: those reported exclusively in SCN (blue, below the gene structure) or those reported predominantly in cyclic neutropenia (but that also may have been described in SCN; pink, above the line). *, amino acid substitutions; ▾, deletions (or nonsense mutations); ▴, an insertion. Exon 4 deletions are in frame, and the cluster of exon 5 deletions are all frame-shift, chain-terminating events.

We have also reported on an ELA2 promoter variant consisting of a single base substitution at a predicted binding sight for the transcription factor LEF1 in some SCN patients, which appears to lead to up-regulation of gene expression.62 The variant has been found to segregate in a pedigree with SCN in another study.63 Nevertheless, we have subsequently appreciated (unpublished, October 2005) that this is a not uncommon polymorphism in the African American population—where there is a higher frequency of “ethnic neutropenia”5 —raising the possibility that overexpression of NE could associate with a lower neutrophil count in healthy individuals. A recent report finds that LEF1 levels are reduced in SCN and are required for neutrophil differentiation.64

Gene targeting in mice

Because hereditary neutropenia resulting from ELA2 mutation is autosomal dominant and the genetic evidence excludes haploinsufficiency, it is not surprising that ELA2 knockout mice65,66 created prior to the discovery of the role of ELA2 in neutropenia are not neutropenic. What is unexpected, however, is that a mouse knock-in of a particular ELA2 mutation (V72M) associated with SCN also lacks a hematopoietic phenotype.67 This could be the result of inherent differences between mouse and human hematopoiesis, but there is another possible explanation. The human and mouse NE sequences are not identical, and the mutations may confer biochemical properties only in the context of the human polypeptide sequence. In fact, the failings of the mouse models have been attributed to demonstrable biochemical differences between the murine and human homologs.68 Expression of a mutant human ELA2 transgene in mice, not yet achieved, may yet result in a neutropenic mouse.

Inconsistent effects of the mutations

Given that NE is a protease, an obvious hypothesis is that the mutations affect its enzymatic properties. It is not practical to purify the mutant proteins from patient neutrophils because they are often neutropenic and have too few neutrophils to prepare sufficient quantities of enzyme, because the mutations occur heterozygously, making it difficult to separate mutant from wild-type protein, and because many of the individuals with this disorder are no longer living or are geographically dispersed. We therefore prepared recombinant enzyme in cultured RBL cells69 and in the yeast Pichia pastoris (unpublished, January 2002–December 2003) and characterized its proteolytic activity. In sum, we found that the mutations had no consistent effect on proteolysis. Some reduced proteolytic activity, but some retained wild-type levels. There was no apparent change in substrate specificity. There was no evident change in the stability of the protein. Studies have shown that while some of the mutations result in aberrant glycosylation,70,71 there are, again, no apparently consistent effects. Similarly, a recent bioinformatic analysis predicted that the various mutations had no obviously common effect on protein structure72 ; however, most of the mutations occurred at phylogenetically conserved residues.

Gfi1 mutations in SCN

Gfi1 is a zinc finger–containing transcriptional repressor originally recognized for its role in T-cell differentiation and lymphogenesis73,74 and that has also recently been shown to regulate hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal.75,76 Gene targeting experiments demonstrated that mice lacking Gfi1 were unexpectedly neutropenic.77,78 We therefore screened Gfi1 as a candidate gene for association with neutropenia in a cohort of neutropenic patients lacking mutations in ELA2. We found rare, heterozygous, dominant-negative zinc finger mutations that disable transcriptional repressor activity in a small family with neutropenia and a sporadic case of mild neutropenia.79 The phenotype in humans differs from most SCN cases, and resembles that of the mouse, to also include immunodeficient lymphocytes and production of a circulating population of immature myeloid cells.

Because mutations in both genes cause similar disease, an obvious question is whether Gfi1 transcriptionally represses ELA2. In fact, the ELA2 promoter does contain a Gfi1 binding motif with repressor activity, demonstrable by electrophoretic mobility shift assays and transient transfection reporter assays in vitro. ELA2 is indeed overexpressed in myeloid progenitor cells from one of the studied neutropenic individuals with a Gfi1 mutation,79 observations corroborated in Gfi1-deficient mice78 and in vitro in murine 32D myeloid cells80 expressing one of the human Gfi1 mutations. Of course, Gfi1 regulates many genes, and it remains to be determined how much, if any, of the neutropenic phenotype arising in its deficiency can be attributed to overexpression of ELA2 rather than being a consequence of deregulation of its other targets.

AP3B1 mutations in canine cyclic neutropenia

Cyclic neutropenia also occurs in dogs.81 In contrast to the human disorder, it is autosomal recessive rather than autosomal dominant, has a cycle length closer to 2 weeks instead of 3, and confers hypopigmentation—which, along for the breed in which it occurs, is why the disease is also known as the “gray collie syndrome.” We used genetic linkage and linkage disequilibrium in inbred collie pedigrees to evaluate ELA2 plus other candidate genes associated with mammalian hematopoiesis and coat color changes. We excluded ELA2 and the other genes and found the trait to be linked to and in linkage disequilibrium with AP3B1. Positional cloning and sequencing of canine AP3B1 revealed a founder mutation consisting of insertion of an adenine in a tract of 9 adenine residues in exon 20 of 27, causing frame shift with premature termination and apparent nonsense-mediated decay of the aberrant message, resulting in reduced levels of mRNA in affected dogs. The mutation, however, creates a hot spot for transcriptional errors resulting in some accumulation of normal mRNA from mutant alleles.82

AP3B1 is responsible for human Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 2 (HPS2), the mouse Pearl mutation, and the Drosophila ruby strain.59 The Hermansky-Pudlak syndromes are genetically heterogeneous autosomal recessive disorders of mammals composed of oculocutaneous albinism and bleeding because of defective platelet granule formation and arising from defects in 1 of at least 8 known human or 16 known mouse genes involved in vesicle biogenesis.83 HPS2 is differentiated from other forms of HPS because it is the only one associated with neutropenia.84–87 In some patients, the severity of neutropenia is similar to that seen with ELA2 mutations in SCN. AP3B1 encodes the β subunit of the heterotetrameric AP3 adapter protein complex. Mammalian cells contain 4 such adapter protein complexes, each of which is involved in protein trafficking along distinct pathways.88 AP3 specifically directs posttranslational trafficking of intraluminal “cargo” proteins from the trans-Golgi network to lysosomes,89 which, in neutrophils, probably equate with the granules where NE is primarily located. Mutation of the β subunit90,91 suffices to prevent assembly of the 4-subunit complex. Either the β or μ subunit of adapter protein complexes can interact with cargo proteins via, respectively, a dileucine repeat or a tyrosine residue near the carboxyl terminus of the cargo.88 Using a yeast 2-hybrid assay established for testing adapter protein subunit and cargo protein interactions, we found that NE lacking the carboxyl terminus interacts with the μ subunit of AP3 and requires a tyrosine residue (NE Y199), as expected if NE were indeed an AP3 cargo protein.92

A model of neutropenia based on mispartitioning between granules and membranes and aberrant feedback

AP3 is a cytoplasmic protein, and cargo proteins are intraluminal; thus, cargo proteins are necessarily transmembrane proteins. If NE is indeed a cargo protein for AP3, NE must cross the trans-Golgi membrane to contact AP3. We consequently evaluated NE for potential transmembrane domains and found that computer algorithms predicted 2 or 3 such domains, and protease protection assays in selectively permeabilized neutrophils provided corroborating support for this topology.92 Moreover, numerous different lines of evidence have shown that NE, even though it is conventionally considered to be a soluble granule protein, can be found in association with the plasma and other subcellular membranes.59 Superimposing the position of the mutations revealed that many of the mutations causing cyclic hematopoiesis aligned with either of the predicted transmembrane domains and that many of the mutations causing SCN deleted the tyrosine residue recognized by the μ subunit of AP3. We therefore have argued that the mutations cause neutropenia through the mistrafficking of NE59,92 : Mutations causing cyclic hematopoiesis would have a propensity to disrupt predicted transmembrane domains and lead to excess granular accumulation of the protein. Mutations causing SCN would tend to disrupt NE's association with AP3 and cause increased routing to cell membranes, and there are several ways this could happen. First, deletions of the carboxyl terminus of NE, which account for the most common sort of SCN mutation, remove the tyrosine-based recognition sequence for the AP3 μ subunit, may prevent granule transport by AP3, and may divert NE to the plasma membrane, which is the default destination for AP3 cargo proteins in the absence of AP3. Second, the absence of AP3, as occurs with canine cyclic neutropenia, would presumably act similarly. Third, overexpression of NE, as is found with mutation of Gfi1 in neutropenic humans and mice, may overwhelm normal AP3-mediated trafficking pathways and lead to spillover into the default membrane trafficking pathway. A test of the model, in which we expressed mutants in RBL cells and performed immunofluorescent microscopic localization along with subcellular fractionation, proved supportive.92 Others have confirmed the subcellular mislocalization to the plasma membrane of both NE mutations causing SCN in normal cells70,93 and of wild-type NE in cells from HPS2 patients who lack AP3B1.85,86 The subcellular localization of the various mutations is not always consistent with the model, and newly reported mutations continue to accumulate across the length of the protein, however. Our assertion that NE is capable of adopting a transmembrane configuration also remains highly speculative. Nevertheless, it does appear that NE mutations do result in mistrafficking of the protein when experimentally expressed.70

If mislocalization of NE is contributory to pathogenesis, what are its effects? Expression of the NE mutation G185R in retrovirally transduced HL-60 promyelocytes confirms that it becomes mislocalized to the plasma membrane91 ; unexpectedly, however, levels of the AP3 complex are also reduced. Thus, one possibility is that mislocalized NE disrupts AP3, which could in turn more profoundly disturb all granule protein trafficking. Another possibility is that NE, with or without mislocalization, may not properly fold and trigger the unfolded protein response. Ectopic expression of some but not all NE mutants does appear to induce the unfolded protein response, at least as measured by the up-regulated expression of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP (GRP78).70,94 NE was also found to interact with BiP in a modified yeast 2-hybrid screen.95 Another possibility is that mislocalized NE retains some proteolytic activity and inappropriately attacks an opportunistic substrate it would not ordinarily encounter. Potential substrates, each capable of being proteolyzed by NE, located in the vicinity of the plasma membrane, and capable of regulating hematopoiesis, include G-CSF,96–98 the G-CSF receptor,97 the c-KIT receptor,99 and Notch proteins.95

Regardless of the precise molecular mechanism, mislocalized (or misfolded) NE must somehow drastically reduce the production of neutrophils from the progenitor cells in the bone marrow. The possibilities are limited: Progenitors of neutrophils can undergo apoptosis, differentiate into other types of cells, or just stop dividing and differentiating. Mutant NE can induce apoptosis at least under some70,93 but not all69 circumstances following its expression in vitro. The progenitor cell for the neutrophil is the same one that produces monocytes, and so another possibility is that myeloid progenitors can produce monocytes instead of neutrophils. This offers a potential explanation for why SCN is accompanied by a relative monocytosis and for why in cyclic neutropenia the monocytes oscillate reciprocally to neutrophils. It is intriguing in this regard that NE was found to associate with Notch2NL, a novel member of the Notch family of proteins, and that NE is capable of digesting Notch2NL and other Notch proteins at the plasma membrane,95 because Notch proteins specify binary cell fate decisions, including in hematopoiesis and at least some aspects of myelopoiesis.100 Finally, it may be that the mutant NE evokes an apathetic response among myeloid progenitor cells, in which they fail to differentiate; certainly, this could account for the characteristic promyelocytic maturation arrest observed in the bone marrow histopathology of SCN patients.

The oscillations in cyclic neutropenia also demand an explanation. Theoretic analysis101,102 has suggested, among other mathematical phenomena, that disruption of a feedback loop could explain cycling. In such a circuit (Figure 3), neutrophils would produce a signal that regulates their differentiation from myeloid progenitors. If that signal were to become overly inhibitory, it would suppress differentiation—but only temporarily, until the cohort of neutrophils producing the signal were themselves exhausted, at which point the next generation of neutrophils would again begin production of the feedback signal. Such a theory recalls the “chalone” hypothesis103 in which it was proposed that neutrophils homeostatically regulate their own production by producing an inhibitor of granulopoiesis. Efforts to track down the chalone led to the purification of a neutrophil membrane extract (the so-called “CAMAL” [common antigen of myelogenous leukemia]) fraction that had the properties of the predicted chalone,104 and subsequently it was shown that NE was the active component of CAMAL.96 Thus, the proposition exists that mispartitioning of mutant NE between granules and the plasma membrane is consistent with an older and more general feedback hypothesis.

Feedback loop hypothesis to explain hematopoietic cycling. NE is postulated to inhibit further differentiation by a myeloblast (red line). Blue sine wave denotes neutrophil count oscillations. In this model, NE is produced by the terminally differentiating cohort of neutrophils and ultimately feeds back to inhibit further production of neutrophils, which results in loss of the inhibitory cycle—at least for a while, until production of neutrophils resume, followed again by the inhibitory action of NE in a cyclic manner.

Feedback loop hypothesis to explain hematopoietic cycling. NE is postulated to inhibit further differentiation by a myeloblast (red line). Blue sine wave denotes neutrophil count oscillations. In this model, NE is produced by the terminally differentiating cohort of neutrophils and ultimately feeds back to inhibit further production of neutrophils, which results in loss of the inhibitory cycle—at least for a while, until production of neutrophils resume, followed again by the inhibitory action of NE in a cyclic manner.

Nevertheless, outstanding questions remain: Is NE the final common effector for all neutropenic disorders? If so, how can mutations in WAS and ultimately other genes be linked to NE? What is the genetic basis for the original families reported by Kostmann in Sweden (excluding the individual with an ELA2 mutation)? Why are ELA2 knock-in mice not neutropenic, and will transgenic expression of ELA2 mutations in the human gene ultimately deliver a hematopoietic phenotype? Is either misfolding or mislocalization of NE sufficient to cause disease and account for the clinical differences between cyclic neutropenia and SCN? Further study of these fascinating and important disorders will no doubt continue to inform our understanding of fundamental hematopoietic mechanisms.

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.H. primarily authored the manuscript, with input from all named authors. All authors contributed to experiments cited within as unpublished studies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marshall S. Horwitz, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Box 357720, Seattle, WA 98195; e-mail: horwitz@u.washington.edu.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 DK58161 and R01 HL079507.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal