Abstract

The nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene encodes for a multifunctional nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein that is localized mainly in the nucleolus. NPM1 mutations occur in 50% to 60% of adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype (AML-NK) and generate NPM mutants that localize aberrantly in the leukemic-cell cytoplasm, hence the term NPM-cytoplasmic positive (NPMc+ AML). Cytoplasmic NPM accumulation is caused by the concerted action of 2 alterations at mutant C-terminus, that is, changes of tryptophan(s) 288 and 290 (or only 290) and creation of an additional nuclear export signal (NES) motif. NPMc+ AML shows increased frequency in adults and females, wide morphologic spectrum, multilineage involvement, high frequency of FLT3-ITD, CD34 negativity, and a distinct gene-expression profile. Analysis of mutated NPM has important clinical and pathologic applications. Immunohistochemical detection of cytoplasmic NPM predicts NPM1 mutations and helps rationalize cytogenetic/molecular studies in AML. NPM1 mutations in absence of FLT3-ITD identify a prognostically favorable subgroup in the heterogeneous AML-NK category. Due to their frequency and stability, NPM1 mutations may become a new tool for monitoring minimal residual disease in AML-NK. Future studies should focus on clarifying how NPM mutants promote leukemia, integrating NPMc+ AML in the upcoming World Health Organization leukemia classification, and eventually developing specific antileukemic drugs.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is clinically, cytogenetically, and molecularly heterogeneous.1 About 30% of cases carry recurrent chromosomal abnormalities that identify leukemia entities with distinct clinical and prognostic features,2 and 10% to 15% of AMLs have nonrandom chromosomal abnormalities. In cytogenetic analysis, 40% to 50% of AMLs show normal karyotype (AML-NK) and, biologically and clinically, are the most poorly understood group.1,3,4 Attempts to stratify AML-NK using gene microarrays5,6 succeeded in associating gene-expression patterns with differences in response to treatment, but no specific genetic subgroups emerged. Molecular analyses of AML-NK identified several mutations that target genes encoding for transcription factors (AML1 and CEBPA: 2%-3% and 15%-20% of cases, respectively),7-10 receptor tyrosine kinases (FLT3 and KIT: 25%-30% and 1%, respectively),11-13 and the RAS genes (10%),14 as well as a partial tandem duplication of MLL gene (MLL-PTD: 5%-10%).15-17

We discovered that nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene mutations target 50% to 60% of adult AML-NK.18 This is the most common genetic lesion described to date in adult de novo AML (about one third of patients).18 Since NPM1 mutations dislocate nucleophosmin into cytoplasm, we named this subgroup NPM-cytoplasmic positive (NPMc+) AML,18 and here we review its biologic and clinical features.

Nucleophosmin (NPM1) gene and protein

Structure of gene and protein

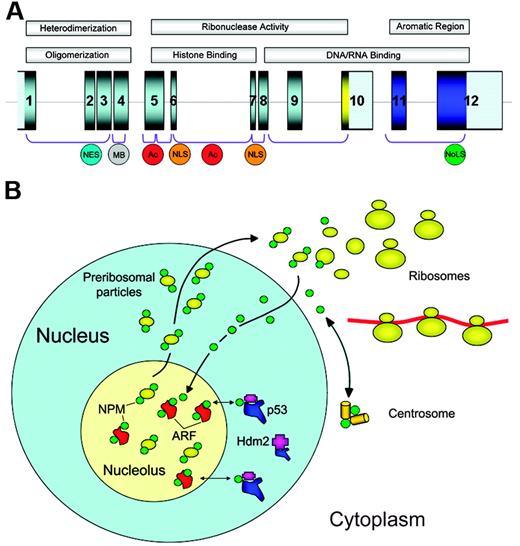

The NPM1 gene, mapping to chromosome 5q35 in humans, contains 12 exons19 (Figure 1A). It encodes for 3 alternatively spliced nucleophosmin isoforms: B23.1 (np_002511), B23.2 (np_954654), and B23.3 (np_001032827).

The NPM1 gene encodes for a protein involved in multiple functions. (A) The NPM1 gene contains 12 exons. NPM1 is translated from exons 1 to 9 and 11 to 12. The portion encoding isoform B23.2 contains exons 1 to 10. In the protein, the N-terminus is characterized by a nonpolar domain responsible for oligomerization and heterodimerization. Functional nuclear export signal (NES) motifs and a metal-binding (MB) domain are present in this region. The central portion of the protein contains 2 acidic stretches (Ac) that are important for binding to histones, and a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS); this region confers ribonuclease activity. The C-terminus of the protein shows ribonuclease activity and contains basic regions involved in nucleic-acid binding. The latter are followed by an aromatic stretch, unique to NPM isoform 1, which contains 2 tryptophan residues (288 and 290), which are required for nucleolar localization of the protein (NoLS). (B) NPM is a nucleolar phosphoprotein that shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Shuttling plays a fundamental role in ribosome biogenesis, since NPM transports preribosomal particles. In cytoplasm, NPM binds to the unduplicated centrosome and regulates its duplication during cell division. Furthermore, NPM interacts with p53 and its regulatory molecules (ARF, Hdm2/Mdm2) influencing the ARF-Hdm2/Mdm2-p53 oncosuppressive pathway.

The NPM1 gene encodes for a protein involved in multiple functions. (A) The NPM1 gene contains 12 exons. NPM1 is translated from exons 1 to 9 and 11 to 12. The portion encoding isoform B23.2 contains exons 1 to 10. In the protein, the N-terminus is characterized by a nonpolar domain responsible for oligomerization and heterodimerization. Functional nuclear export signal (NES) motifs and a metal-binding (MB) domain are present in this region. The central portion of the protein contains 2 acidic stretches (Ac) that are important for binding to histones, and a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS); this region confers ribonuclease activity. The C-terminus of the protein shows ribonuclease activity and contains basic regions involved in nucleic-acid binding. The latter are followed by an aromatic stretch, unique to NPM isoform 1, which contains 2 tryptophan residues (288 and 290), which are required for nucleolar localization of the protein (NoLS). (B) NPM is a nucleolar phosphoprotein that shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Shuttling plays a fundamental role in ribosome biogenesis, since NPM transports preribosomal particles. In cytoplasm, NPM binds to the unduplicated centrosome and regulates its duplication during cell division. Furthermore, NPM interacts with p53 and its regulatory molecules (ARF, Hdm2/Mdm2) influencing the ARF-Hdm2/Mdm2-p53 oncosuppressive pathway.

B23.1, the prevalent isoform,20 is a 294–amino acid protein of about 37 kDa, which shares a conserved N-terminal region with the other nucleophosmin isoforms and has multiple functional domains.21,22 The N-terminus portion contains a hydrophobic region,21,22 regulating self-oligomerization23 and NPM chaperone activity toward proteins, nucleic acids, and histones.24,25 In resting and proliferating cells, more than 95% of NPM is present as an oligomer26 ; both the nonpolar N-terminus region21 and multimeric state of NPM26 appear to be crucial for proper assembly of maturing ribosomes in the nucleolus. The middle portion of NPM contains 2 acidic stretches that are critical for histone binding25 ; the segment between the acidic stretches exerts ribonuclease activity.21 The C-terminal domain, with its basic regions involved in nucleic acid binding and ribonuclease activity,21,22 is followed by an aromatic short stretch encompassing tryptophans 288 and 290, which are critical for NPM binding to nucleolus.27 B23.1 is also equipped with a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS),21,22 leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) motifs,28,29 and several phosphorylation sites regulating its association with centrosomes30 and subnuclear compartments.31,32 In immunocytochemical analysis, B23.1 shows restricted nucleolar localization.20

B23.2, a truncated isoform, lacks the last 35 C-terminal amino acids of B23.1 (containing the nucleolar-binding domain) and is found in tissues at very low levels. In immunocytochemical analysis, B23.2 is located in nucleoplasm.33 Little information is available on the B23.3 isoform, which consists of 259 amino acids.

Expression and functions of NPM protein

Nucleophosmin is a highly conserved phosphoprotein that is ubiquitously expressed in tissues.34 It is one of the most abundant of the approximately 700 proteins identified to date in the nucleolus by proteomics.35,36 Although the bulk of NPM resides in the granular region of the nucleolus,36,37 it shuttles continuously between nucleus and cytoplasm,38,39 as proven by interspecies heterokaryon assays. NPM nucleocytoplasmic traffic is strictly regulated, since important NPM functions, including transport of ribosome components to the cytoplasm and control of centrosome duplication, are closely related to its ability to actively mobilize into distinct subcellular compartments.28,29 Here, we briefly discuss some of the major functions of NPM that have been recognized so far (Figure 1B).

NPM plays a key role in ribosome biogenesis providing the necessary export signals and chaperoning capabilities that are required to transport components of the ribosome from nucleus to cytoplasm. A major role of NPM is to mediate, through a Crm1-dependent mechanism, nuclear export of the ribosomal protein L5/5S rRNA subunit complex.29 Other elements that implicate NPM in the processing and/or assembly of ribosomes are its nucleocytoplasmic shuttling properties and intrinsic RNAse activity,40 and the ability to bind nucleic acids,41 to process pre-RNA molecules,42 and to act as a chaperone,24 thus preventing protein aggregation in the nucleolus during ribosome assembly.23 Because it can directly access maturing ribosomes and potentially regulate the protein translational machinery,29 NPM seems to play a central role in balancing protein synthesis, and cell growth and proliferation. This view concurs with evidence that closely correlates NPM overexpression with cell proliferation43 ; for example, in bone marrow, NPM positivity progressively decreases as cells mature from proerythroblasts to normoblasts and from promyelocytes to neutrophils (B.F., personal observation, January 2005). Moreover, NPM overexpression promotes survival and recovery of hematopoietic stem cells under stress conditions44 ; high NPM levels in malignant cells promote aberrant cell growth by enhancing ribosome machinery. Conversely, inhibition of NPM shuttling or NPM loss block protein translation and produce cell-cycle arrest.29

NPM also maintains genomic stability,45,46 controlling DNA repair47 and centrosome duplication48 during mitosis. NPM associates with the unduplicated centrosome in resting cells and dissociates from it after CDK2-cyclinE–mediated phosphorylation on threonine 199,49 thus enabling proper chromosome duplication. NPM reassociates with centrosomes at the mitotic spindle during mitosis as a result of phosphorylation on serine 4 by PLK150 and NEK2A.51 NPM seems to protect from centrosome hyperamplification as its inactivation causes unrestricted centrosome duplication and genomic instability,45,52 with increased risk of cellular transformation.

Finally, NPM interacts with the oncosuppressors p53 and p19Arf and their partners (ie, Hdm2/Mdm2), thus controlling cell proliferation and apoptosis.53

(1) Interaction with p53.

NPM regulates p53 levels and activity. A functional link exists between nucleolar integrity, NPM, and p53 stability,54,55 since stimuli inducing cellular stress (eg, UV radiation or drugs interfering with rRNA processing) lead to loss of nucleolar integrity, relocation of NPM from nucleolus to nucleoplasm, and p53 activation.55,56 Nucleoplasmic NPM increases p53 stability by binding to, and inhibiting, Hdm2/Mdm257 (a p53 E3-ubiquitin ligase), although “nucleolar stress” can also activate p53 in an Hdm2/Mdm2-independent fashion.58,59 Thus, under stress conditions, the nucleolus functions as a “stress-sensor” with NPM playing a key role in potentiating p53-dependent cell-cycle arrest.57 NPM-p53 cross talk may also involve proteins that are downstream targets of p53 (eg, GADD45α).60

(2) Interaction with ARF.

In cultured unstressed cells, most NPM and ARF colocalize in the nucleolus, in high-molecular-weight complexes containing other nucleolar proteins.61 The NPM-ARF interaction helps stabilize both proteins, since ARF influences NPM polyubiquitination62 and NPM protects ARF from degradation.46,63 The functional significance of NPM and ARF interactions is still in debate.64 There is evidence that ARF targets NPM into nucleoli for degradation,62 that the ARF-NPM complex sequesters Hdm2/Mdm2 into the nucleolus thereby activating p53 in the nucleoplasm,65 that ARF impedes NPM shuttling, thereby producing cell-cycle arrest in a p53-independent fashion,66 and that NPM sequesters ARF into the nucleolus, impairs ARF-Hdm2/Mdm2 association, and inhibits ARF's p53-dependent activation.67 Despite these uncertainties, NPM and ARF activities appear closely coordinated and regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis65 through precise subnuclear compartmentalization.68

In response to cellular stress, NPM and ARF are redistributed to the nucleoplasm.68 Competition between Hdm2/Mdm2 and NPM for ARF binding promotes formation of NPM-Hdm2/Mdm2 and ARF-Hdm2/Mdm2 binary complexes and strongly activates the p53 pathway.69 Thus, through its nucleolar association with NPM, ARF may directly access ribosome function to inhibit cell growth, and via its nucleoplasmic interaction with Hdm2/Mdm2 and ARF-BP1,70 it may regulate the p53 cell-cycle pathway.

Discovery of NPM1 mutations in AML

NPM1 is translocated to several partner genes in various hematopoietic malignancies,71 including CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with t(2;5),72 the rare myelodysplasia/AML with t(3;5),73 and exceptional cases of promyelocytic leukemia with t(5;17).74 Translocations create chimeric genes encoding for fusion proteins (NPM-ALK,72 NPM-MLF1,73 and NPM-RARα74 ), which form heterodimers with wild-type NPM (NPMwt) and promote cellular transformation. Since proper NPM function is closely dependent on its levels in different cell compartments, we wondered whether NPM fusion proteins have a different subcellular distribution to NPMwt and whether this finding could be exploited for diagnostic purposes. In the late 1980s, we generated monoclonal antibodies against fixative-resistant epitopes of NPM protein34 to investigate NPM subcellular expression in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma carrying the NPM-ALK fusion protein compared with normal tissues. We found that, because of NPM-ALK chimeric protein, this lymphoma was associated with NPM expression in cytoplasm75 instead of in the nucleolus as in normal tissues.34 Reasoning that detection of aberrant cytoplasmic NPM might provide a simple way of immunoscreening routine bioptic samples for potential NPM1 gene alterations, we extended our immunohistochemical investigations to a range of human tumors, including leukemias. In 1999, we observed our first AML cases with cytoplasmic NPM but no known NPM fusion proteins, and named them NPMc+ AML to distinguish them from NPMc− AML, which showed the expected nucleus-restricted NPM expression. Subsequently, in 591 AML patients enrolled in the GIMEMA/AML12 EORTC trial, we observed cytoplasmic NPM is mutually exclusive of major chromosomal abnormalities, closely associates with normal karyotype, and has distinctive biologic and clinical features.18 These findings led us to hypothesize that an as-yet-unidentified genetic lesion of NPM1 gene underlayed NPMc+ AML, and indeed gene sequencing revealed mutations at exon 12.18

Characteristics of NPM1 mutations

NPM1 mutations are reliably identified by various molecular biology techniques,76,77 which also allow simultaneous detection of NPM1 and FLT3-ITD or CEBPA mutations78,79 (all prognostically relevant in AML-NK10,80-83 ).

Immunohistochemical detection of cytoplasmic NPM in AML is predictive of NPM1 mutations.84 The main advantages of immunohistochemistry are simplicity, low cost, and ability to correlate cytoplasmic NPM with morphology and topographic distribution of leukemic cells. Moreover, immunohistochemistry is the first-choice technique for detecting NPM1 mutations in cases of dry-tap or small biopsies (eg, skin involvement in myeloid sarcoma85 ), and also helps rationalize cytogenetic/molecular studies in AML.84

The choice of technique for detecting NPM1 mutations at diagnosis may be based on the investigator's experience, costs, available equipment, application of bone marrow trephine for AML diagnosis, among other factors. Immunohistochemistry is not suitable for monitoring minimal residual disease in NPMc+ AML.

Specificity of NPM1 mutations

NPM1 mutations are AML specific since other human neoplasms consistently show nucleus-restricted NPM expression.18 They have been sporadically detected in chronic myeloproliferative disorders (5/200 cases investigated; 2.5%).86,87 All 5 cases were chronic myelomonocytic leukemias and 4 quickly progressed to overt AML in less than 1 year, suggesting they represented M4 or M5 AMLs with marked monocytic differentiation (often targeted by NPM1 mutations18,80 ). NPM1 mutations were found in only 2 (5.2%) of 38 myelodysplastic patients.88 However, caution is needed when defining a case as “NPM1-mutated myelodysplastic syndrome” since NPMc+ AML frequently shows multilineage involvement and dysplastic features.89 NPM1 mutations closely associate with de novo AML, as AML secondary to myeloproliferative disorders/myelodysplasia and therapy-related AML rarely show cytoplasmic NPM.18

Types, frequency, and stability of NPM1 mutations

A polymorphism of nucleotide T deletion at position 1146 in the NPM1 3′-untranslated region has been reported in 60% to 70% of AMLs and in healthy volunteers.81,90 NPM1 mutations are characteristically heterozygous and retain a wild-type allele. In children with AML, their incidence ranges from 2.1% in Taiwan90 to 6.5% in Western countries,91,92 accounting for 9% to 26.9% of all childhood AML-NK.90-92 In about 3000 adult AML patients, the frequency of NPM1 mutations ranged between 25% and 35%,80-83,90,93,94 accounting for 45.7% to 63.8% of adult AML-NK.80-83,90,93,94 This suggests the molecular pathogenesis of AML-NK is different in adults and children.

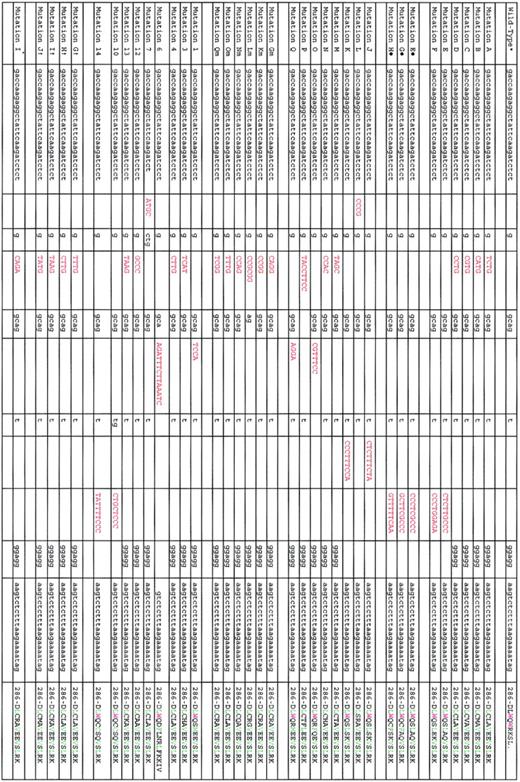

Except for 2 cases involving the splicing donor site of NPM1 exon 995 and exon 11,96 mutations are restricted to exon 1218,80-83,93,94 (Figure 2). The most common NPM1 mutation, which we named mutation A,18 is a duplication of a TCTG tetranucleotide at position 956 to 959 of the reference sequence (GenBank accession number NM_002520) and accounts for 75% to 80% of cases. Mutations B and D are observed in about 10% and 5% of NPMc+ AML; other mutations are very rare (Figure 2).

List of exon 12 NPM1 mutations so far identified in AML patients. Red coloring indicates nucleotides inserted by mutations; green, leucine-rich NES motif; violet, tryptophan (W) residues; L, leucine; C, cysteine; V, valine; M, methionine; and F, phenyl-alanine. Mutations A to F refer to those we originally identified.18 Mutations E to H refer to those we identified in childhood AML.91 Mutations J to Q refer to those subsequently identified in Falini et al.84 Mutations Gm to Qm refer to those we identified in the protocol 99 of the German AML cooperative group.80 Mutations 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, 10, and 14 are according to Dohner et al.81 Mutation I* is according to Verhaak et al.82 *NM_002520. †Mutations G, I, H, and J are according to Suzuki et al.93

List of exon 12 NPM1 mutations so far identified in AML patients. Red coloring indicates nucleotides inserted by mutations; green, leucine-rich NES motif; violet, tryptophan (W) residues; L, leucine; C, cysteine; V, valine; M, methionine; and F, phenyl-alanine. Mutations A to F refer to those we originally identified.18 Mutations E to H refer to those we identified in childhood AML.91 Mutations J to Q refer to those subsequently identified in Falini et al.84 Mutations Gm to Qm refer to those we identified in the protocol 99 of the German AML cooperative group.80 Mutations 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 13, 10, and 14 are according to Dohner et al.81 Mutation I* is according to Verhaak et al.82 *NM_002520. †Mutations G, I, H, and J are according to Suzuki et al.93

Alterations of the NPM1 gene appear more stable than those of FLT3 gene.93 Loss of NPM1 mutations at relapse is rare and may be due either to emergence of a different leukemic clone or inability to detect mutations because few leukemic blasts are infiltrating the marrow.90 In some cases, loss of NPM1 mutations was associated with change from normal to abnormal karyotype.90,93 AML patients with a germ-line NPM1 gene at diagnosis do not appear to acquire NPM1 mutations during the course of disease, suggesting that mutations play a scarce role in disease progression.90

Relationship between NPM1 mutations, karyotype, and other mutations

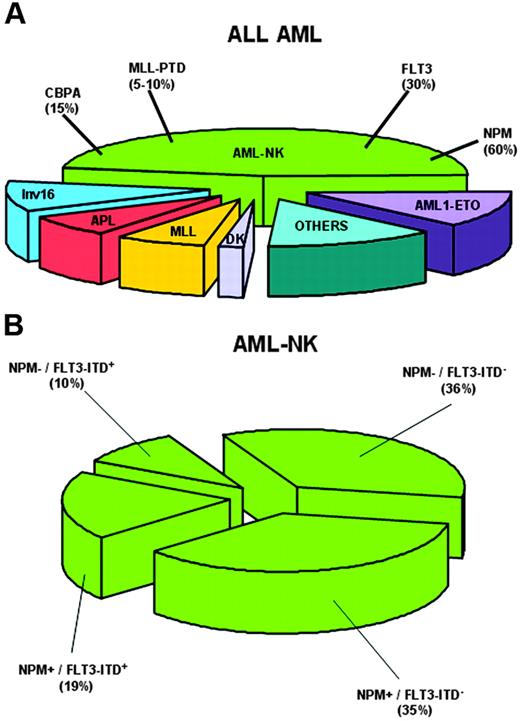

Cytoplasmic NPM closely associates with normal karyotype (Figure 3A) and is mutually exclusive of recurrent genetic abnormalities,18 as confirmed by NPM1 mutational analysis of thousands of AML patients.80-83,91,93,94 Chromosomal abnormalities observed in a minority of NPMc+ AMLs (14%)18 are probably secondary because (1) they are similar, in type and frequency, to secondary chromosomal changes occurring in AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities97 ; (2) cells with an abnormal karyotype represent subclones within the leukemic population with normal karyotype18 ; and (3) these abnormalities occasionally occur at relapse in patients with AML-NK at diagnosis (B.F., unpublished observations, September 2005).

NPM1 mutations closely associate with AML-NK and FLT3-ITD. (A) Pie chart showing cytogenetic alterations in adult AML and frequency of NPM1 gene mutations in AML with normal karyotype (AML-NK). (B) Pie chart showing relationship between NPM1 mutations and FLT3-ITD in AML-NK.

NPM1 mutations closely associate with AML-NK and FLT3-ITD. (A) Pie chart showing cytogenetic alterations in adult AML and frequency of NPM1 gene mutations in AML with normal karyotype (AML-NK). (B) Pie chart showing relationship between NPM1 mutations and FLT3-ITD in AML-NK.

Several studies80-83,93 confirmed our original observation that NPMc+ AML is preferentially targeted by FLT3-ITD18 (Figure 3B). NPM1 and FLT3-TKD correlated in some studies,80,81,93 but not in others.18,82 Thiede et al83 found NPM1 mutations are primary events that precede acquisition of FLT3-ITD or other mutations.

MLL-PTD rarely coincides with cytoplasmic/mutated NPM.18 Some authors80,81 reported no difference in frequency of CEBPA mutations in NPM1-mutated versus NPM1-unmutated AML-NK, while Chou et al90 found a negative correlation between NPM1 and CEBPA mutations. KIT and NRAS mutations were not significantly associated with NPM1 mutations.80,81 KRAS mutations were reported in 5 of 8 AML with NPM1 mutations.82 Unsurprisingly, TP53 mutations rarely occur in NPMc+ AML,93 as they mostly associate with karyotypic abnormalities,98,99 while NPM1 mutations are typical of AML-NK.

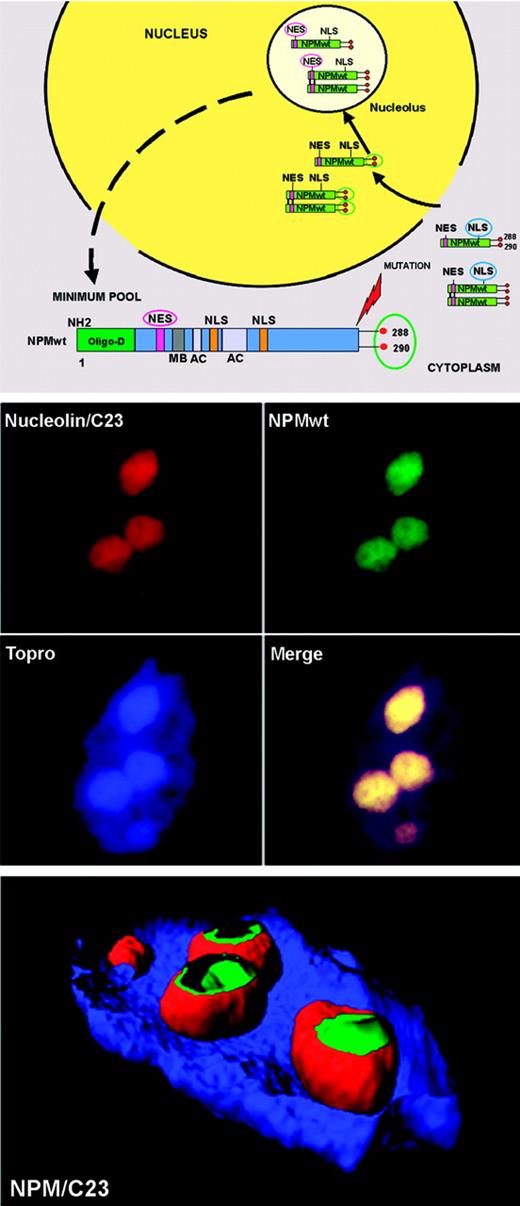

Nucleocytoplasmic traffic of wild-type NPM

Although NPMwt is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein,38 its expression is restricted to the nucleolus.34,37 Explanation comes from analysis of NPM functional domains (Figure 4 top). The NLS signal drives NPM from cytoplasm to nucleoplasm, where it is translocated to the nucleolus through its nucleolar-binding domain, particularly tryptophans 288 and 290.27 Nuclear export of NPM (and of proteins in general) is mediated by the evolution-conserved Crm1 (also called exportin 1),100,101 the export receptor of proteins containing leucine-rich NES motifs with the generally accepted loose consensus L-x(2,3)-(LIVFM)-x(2,3)-L-x-(LI),102 a core of closely spaced leucines or other large hydrophobic amino acids. Two such highly conserved NES motifs have been identified in the NPMwt protein: one with the sequence I-xx-P-xx-L-x-L within residues 94 to 10228 and another at the N-terminus within amino acids 42 to 61, with leucines 42 and 44 as critical nuclear export residues.29 However, despite the NES motifs, NPM remains localized in nucleoli (Figure 4 middle and bottom panels). Thus, in physiologic conditions, nuclear import of NPMwt greatly predominates over export (Figure 4 top panel), since NPMwt's NES motifs exhibit the general property of NES motifs (ie, weak interaction with Crm1).103,104 Knowledge of how NPMwt nucleocytoplasmic traffic is regulated at the steady state is fundamental to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying aberrant cytoplasmic NPM expression in AML.18

NPM, a shuttling protein, is mainly localized in the nucleolus. (Top) Mechanism of nucleocytoplasmic traffic of NPM wild-type (NPMwt). Green boxes indicate NPMwt protein; red circles, tryptophan residues; NES motif, nuclear export signal motif; and NLS, nuclear localization signal. The nuclear import of NPM (arrows) greatly predominates over the nuclear export (dotted arrow). Thus, NPM is mainly localized in the nucleolus. (Middle) Confocal analysis of NIH-3T3 cells expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)–NPMwt fusion protein. The bulk of NPMwt (green) colocalizes in nucleoli with C23/nucleolin (red), as revealed using a specific antibody. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a Plan Apochromat 100×/1.4 NA oil objective and the LSM 5 software (Zeiss) for image acquisition. An Alexa 543-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used for C23/nucleolin staining; nuclei were stained with To-Pro3 (Molecular Probes). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the confocal images and electronic cuts of nucleus and nucleoli to analyze the subcellular distribution of NPMwt (green) and C23 (red) proteins were performed with Imaris software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland).

NPM, a shuttling protein, is mainly localized in the nucleolus. (Top) Mechanism of nucleocytoplasmic traffic of NPM wild-type (NPMwt). Green boxes indicate NPMwt protein; red circles, tryptophan residues; NES motif, nuclear export signal motif; and NLS, nuclear localization signal. The nuclear import of NPM (arrows) greatly predominates over the nuclear export (dotted arrow). Thus, NPM is mainly localized in the nucleolus. (Middle) Confocal analysis of NIH-3T3 cells expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)–NPMwt fusion protein. The bulk of NPMwt (green) colocalizes in nucleoli with C23/nucleolin (red), as revealed using a specific antibody. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a Plan Apochromat 100×/1.4 NA oil objective and the LSM 5 software (Zeiss) for image acquisition. An Alexa 543-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used for C23/nucleolin staining; nuclei were stained with To-Pro3 (Molecular Probes). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the confocal images and electronic cuts of nucleus and nucleoli to analyze the subcellular distribution of NPMwt (green) and C23 (red) proteins were performed with Imaris software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland).

Altered nucleocytoplasmic traffic of nucleophosmin in NPMc+ AML

In NPMc+ AML, aberrant cytoplasmic NPM localization, which is easily detected by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5), is caused by 2 mutation-related alterations at the C-terminus of NPM leukemic mutants105 : (1) generation of an additional leucine-rich NES motif,106 reinforcing Crm1-dependent nuclear export of mutated NPM proteins105 ; and (2) loss of tryptophan residues 288 and 290 (or residue 290 alone)18 , which determine NPM nucleolar localization.27 Both alterations are crucial for perturbing NPM mutant traffic105 (Figure 6).

Cytoplasmic NPM and multilineage involvement in NPMc+ AML. (Top, left) Myeloid sarcoma (skin, paraffin section). Nuclear plus aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in leukemic blasts. Normal residual vessel endothelial cells show the expected nucleus-restricted NPM expression (arrow). Immunostaining with monoclonal antibody 376 that recognizes both wild-type and mutated NPM (alkaline phosphatase anti–alkaline phosphatase [APAAP] technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlanApo 40×0.85 NA objective). (Top, right) NPMc+ AML (bone marrow biopsy, paraffin section). Cytoplasmic-restricted expression of mutant NPM protein in leukemic cells (arrow). A normal residual megakaryocyte is negative (double arrows). Immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody (Sil-A) that recognizes mutated but not wild-type NPM (APAAP technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective). (Bottom, left) NPMc+ AML with multilineage involvement (bone marrow biopsy, image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UplanApo 40×/0.85 NA objective). Double APAAP/immunoperoxidase staining for NPM (blue) and glycophorin (brown). Aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in proerythroblasts (arrow), megakaryocytes (double arrows), and myeloid blasts surrounding a blood vessel (asterisk). (Bottom, right) Higher magnification (image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective) from a different field of the same case. Proerythroblasts are strongly NPMc+ (blue) and weakly positive or negative for glycophorin (brown) (long arrow), while more mature erythroid precursors show nucleus-restricted NPM(blue)/strong surface glycophorin (brown) (short arrow). Double arrows indicate a NPMc+/glycophorin-negative megakaryocyte. A myeloid blast is positive for cytoplasmic NPM (blue) and negative for surface glycophorin (arrowhead).

Cytoplasmic NPM and multilineage involvement in NPMc+ AML. (Top, left) Myeloid sarcoma (skin, paraffin section). Nuclear plus aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in leukemic blasts. Normal residual vessel endothelial cells show the expected nucleus-restricted NPM expression (arrow). Immunostaining with monoclonal antibody 376 that recognizes both wild-type and mutated NPM (alkaline phosphatase anti–alkaline phosphatase [APAAP] technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlanApo 40×0.85 NA objective). (Top, right) NPMc+ AML (bone marrow biopsy, paraffin section). Cytoplasmic-restricted expression of mutant NPM protein in leukemic cells (arrow). A normal residual megakaryocyte is negative (double arrows). Immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody (Sil-A) that recognizes mutated but not wild-type NPM (APAAP technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective). (Bottom, left) NPMc+ AML with multilineage involvement (bone marrow biopsy, image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UplanApo 40×/0.85 NA objective). Double APAAP/immunoperoxidase staining for NPM (blue) and glycophorin (brown). Aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in proerythroblasts (arrow), megakaryocytes (double arrows), and myeloid blasts surrounding a blood vessel (asterisk). (Bottom, right) Higher magnification (image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective) from a different field of the same case. Proerythroblasts are strongly NPMc+ (blue) and weakly positive or negative for glycophorin (brown) (long arrow), while more mature erythroid precursors show nucleus-restricted NPM(blue)/strong surface glycophorin (brown) (short arrow). Double arrows indicate a NPMc+/glycophorin-negative megakaryocyte. A myeloid blast is positive for cytoplasmic NPM (blue) and negative for surface glycophorin (arrowhead).

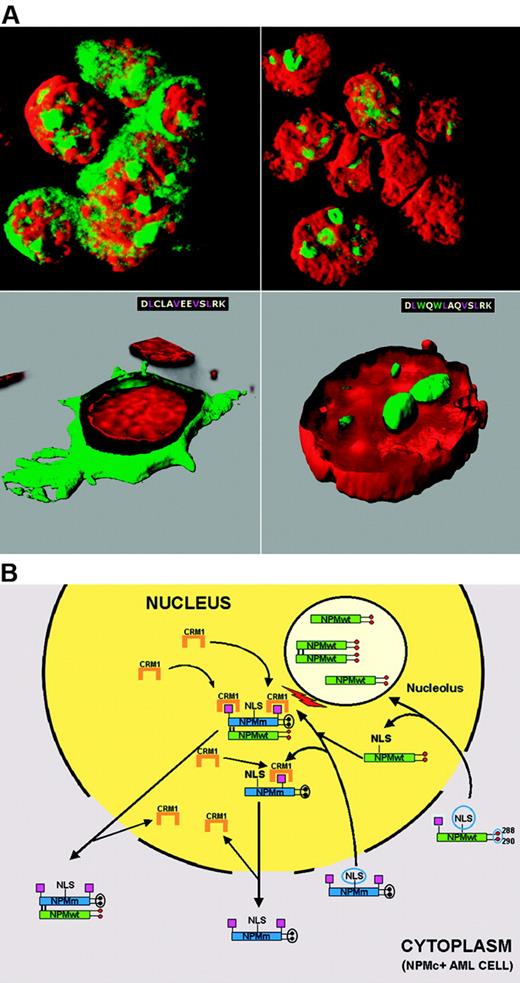

Mechanism of perturbed NPM nucleocytoplasmic traffic in NPMc+ AML. (A) Cytoplasmic accumulation of NPM is NES-dependent. OCI-AML3 cell line carrying the NPM1 mutation A shows cytoplasmic (and nucleolar) positivity for NPM (green) (top, left). NPM is relocated into the nucleus after exposure to the Crm1 inhibitor leptomycin B (top, right). Cytoplasmic accumulation of NPM is tryptophan dependent. In NIH-3T3 cells, NPM mutant A is relocated from cytoplasm (green, bottom, left) into nucleoli (green, bottom right), after the 2 tryptophans (W) are reinserted at positions 288 and 299. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using a Plan Apochromat 100×/1.4 NA oil objective and LSM 5 software for image acquisition. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (Molecular Probes). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the confocal images and electronic cuts of cells were performed with Imaris software. (B) Hypothetical mechanism of altered nucleocytoplasmic traffic of NPM mutant A and NPMwt. Green boxes indicate NPMwt protein; blue boxes, mutated NPM protein; red circles, tryptophan residues; black circles, mutated tryptophans; magenta boxes, NES motif; and NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Mechanism of perturbed NPM nucleocytoplasmic traffic in NPMc+ AML. (A) Cytoplasmic accumulation of NPM is NES-dependent. OCI-AML3 cell line carrying the NPM1 mutation A shows cytoplasmic (and nucleolar) positivity for NPM (green) (top, left). NPM is relocated into the nucleus after exposure to the Crm1 inhibitor leptomycin B (top, right). Cytoplasmic accumulation of NPM is tryptophan dependent. In NIH-3T3 cells, NPM mutant A is relocated from cytoplasm (green, bottom, left) into nucleoli (green, bottom right), after the 2 tryptophans (W) are reinserted at positions 288 and 299. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using a Plan Apochromat 100×/1.4 NA oil objective and LSM 5 software for image acquisition. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (Molecular Probes). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the confocal images and electronic cuts of cells were performed with Imaris software. (B) Hypothetical mechanism of altered nucleocytoplasmic traffic of NPM mutant A and NPMwt. Green boxes indicate NPMwt protein; blue boxes, mutated NPM protein; red circles, tryptophan residues; black circles, mutated tryptophans; magenta boxes, NES motif; and NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Role of the additional C-terminus NES motif

Specific exportin-1/Crm1-inhibitors107 (leptomycin-B and ratjadones) block cytoplasmic NPM accumulation, demonstrating that export of NPM mutants is NES dependent105 (Figure 6A top panels). How can we reconcile this finding with the observation that NPMwt, despite the presence of physiologic NES motifs,28,29 is restricted to nucleolus? Comparative analysis of artificial and leukemic NPM mutants provides the answer. Artificial NPMwt mutants lacking tryptophans 288 and 290 delocalize from nucleolus to nucleoplasm but do not accumulate into cytoplasm,27,28 due to the weak activity of the physiologic NES motifs; a similar picture is observed with the C-terminus truncated B23.2 isoform.33 In contrast, NPM leukemic mutants, which also lack C-terminus tryptophan(s), accumulate in the cytoplasm, since the new C-terminus NES motif acts as the additional force causing their overexport from nucleus to cytoplasm.105

Role of C-terminal tryptophans

The C-terminus NES motif is, however, insufficient in itself, for nuclear export of NPM mutants105 because reinserting residues 288 and 290 (which are both critical for nucleolar binding27 ) relocates NPM mutants to nucleoli (Figure 6A bottom panels).

More than 95% of NPM leukemic mutants lack tryptophans 288 and 290; the others retain tryptophan 288. Despite this difference, all mutants are aberrantly dislocated in the cytoplasm, implying that their nuclear export occurs even when tryptophan 288 is present. The explanation comes from analysis of the relationship between mutated tryptophans and types of NES motif at the C-terminus of leukemic mutants.105 Mutations of both tryptophans are usually associated with the most common NES motif (ie, L-xxx-V-xx-V-x-L); retention of tryptophan 288 is always associated with variants of this NES motif (ie, replacement of valine at the second position with leucine, phenyl-alanine, cysteine, or methionine).105 Therefore, to ensure NPM mutants are dislocated into cytoplasm, variant NES motifs likely need to be more efficient than L-xxx-V-xx-V-x-L, so as to counterbalance the action of tryptophan 288, which drives mutants to the nucleolus.27 That NES motifs may differ in their activity, influencing the ability of a given protein to be exported from the nucleus more or less efficiently, is a known phenomenon,108,109 which may also apply to NPM leukemic mutants.

A hypothetical scheme of NPM nucleocytoplasmic traffic in NPMc+ AML is shown in Figure 6B. NPM mutants retain the NLS and can, therefore, enter the nucleus. Their capability to bind nucleoli is hindered completely (when both tryptophans are mutated) or partially (when only tryptophan 290 is altered). The additional C-terminus NES motif (L-xxx-V-xx-V-x-L if both tryptophans are mutated, or a variant NES motif if tryptophan 288 is retained) probably renders the mutants more available for binding to Crm1 in nucleoplasm. Under these circumstances, the NES-Crm1–mediated nuclear export of NPM mutants is more efficient than nuclear import and they accumulate in cytoplasm.

There is now evidence that NPM mutants recruit NPMwt from nucleoli and delocalize it into nucleoplasm and cytoplasm,105,110 perhaps altering its functions. Recruitment occurs through the N-terminal dimerization domain that is conserved in all NPM mutants, allowing them to form heterodimers with NPMwt, as occurs between NPMwt and NPM fusion proteins.71,111,112 NPM also interacts with ARF and delocalizes it into cytoplasm.110,113

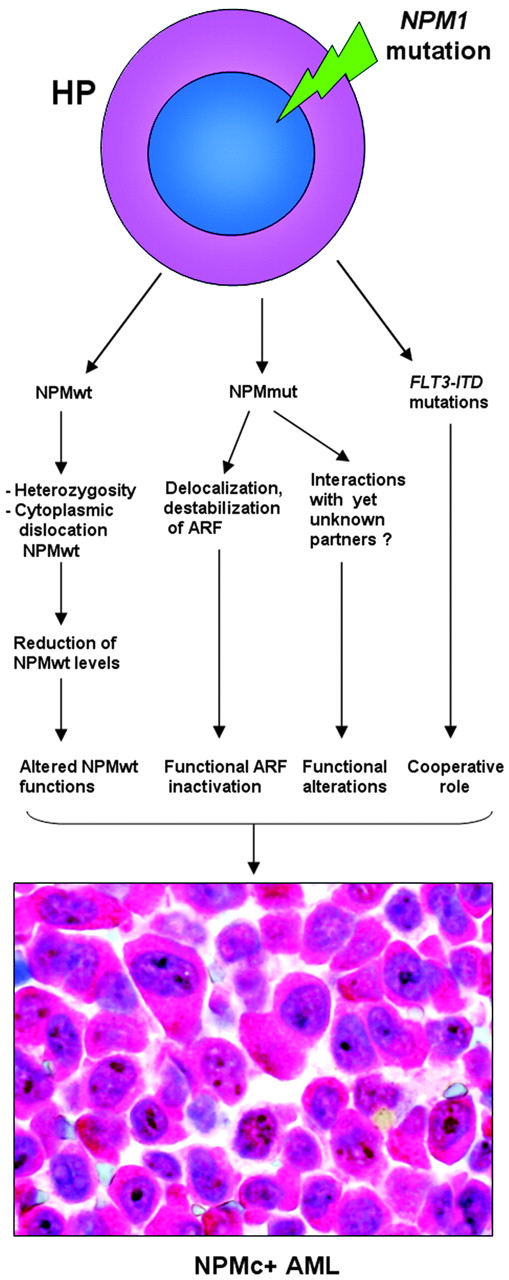

Role of NPM mutants in leukemogenesis

NPM1 belongs to a new category of genes that function both as oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes,114 depending on gene dosage, expression levels, interacting partners, and compartmentalization. NPM1 appears implicated in promoting cell growth, as its expression increases in response to mitogenic stimuli and above-normal amounts are detected in highly proliferating and malignant cells. On the other hand, since NPM contributes to growth-suppressing pathways through its interaction with ARF, loss of NPM expression or function can contribute to tumorigenesis.

At present, no experimental models exist for NPMc+ AML. In NPM knock-out mice, NPM is involved in control of primitive hematopoiesis (especially erythropoiesis), and NPM is haploinsufficient for the control of proper centrosome duplication, resulting in genomic instability and development of a hematologic syndrome reminiscent of human myelodysplasia.45 In NPMc+ AML, since one NPM allele is mutated and NPM mutants dislocate the NPMwt encoded by the uninvolved allele into cytoplasm, one might argue that blasts show a form of NPM haploinsufficiency. However, NPMc+ AML is characterized by normal karyotype as NPM mutants are still effective in binding to, and controlling, centrosome duplication. Furthermore, NPM1 mutations are extremely rare in human myelodysplasia, being characteristically associated with de novo AML.

Therefore, other mechanisms, probably related to inherent NPM mutant properties, may operate in humans to promote leukemic transformation. Cytoplasmic NPM may contribute to AML development by inactivating ARF, a critical antioncogene.115 In NIH-3T3 fibroblasts engineered to produce a zinc-inducible ARF protein, human leukemic NPM mutant A delocalizes NPMwt and ARF from nucleoli to cytoplasm,110 resulting in reduced p53-dependent (Hdm2/Mdm2 and p21cip1 induction) and p53-independent (ARF-induced sumoylation of NPM and Hdm2/Mdm2) ARF activities.110 When complexed with NPM mutant, ARF stability was greatly compromised and the p53-dependent cell-cycle arrest at the G1/S boundary was appreciably lower.113 ARF is only one of the potential targets of NPM mutants, and new molecules are expected to be found that could interact with NPM mutants and contribute to leukemogenesis. A hypothetical scheme of the molecular events underlying NPMc+ AML is shown in Figure 7.

Pathologic and clinical features of NPMc+ AML

NPMc+ AML shows a wide morphologic spectrum.18 However, NPM1 mutations are more frequent in M4 and M5 FAB categories,18,80,81 and in AML with prominent nuclear invaginations (“cuplike” nuclei).116 More than 95% of NPMc+ AMLs are CD34−.18 Involvement of several cell lineages (myeloid, monocytic, erythroid, and megakaryocytic but not lymphoid)89 (Figure 5) is another distinctive, apparently intrinsic feature of NPMc+ AML that is independent of additional genetic alterations, such as FLT3-ITD. High frequency of multilineage involvement is somewhat surprising since NPMc+ AML is usually a de novo leukemia,18 and multilineage involvement is mainly associated with secondary leukemias.117

The blast count is higher in NPM-mutated than NPM–germ-line AML-NK,81,83 and rises with concomitant FLT3-ITD83 and LDH serum levels.81 NPM1 mutations correlate with extramedullary involvement, mainly gingival hyperplasia and lymphadenopathy,81 possibly because this extramedullary dissemination pattern is mostly seen with M4 and M5 AML,2 which are frequently targeted by NPM1 mutations.80,81

Platelet counts are higher in NPM-mutated than NPM–germ-line AML-NK.81,83 Of interest, bone marrow biopsies from NPMc+ AML (especially M4) frequently show increased number of megakaryocytes carrying mutated NPM and exhibiting dysplastic features.89 These findings suggest that megakaryocytes with NPM1 mutations retain a certain capacity for thrombocytic differentiation.

NPM1 mutations are more frequent in female patients,80,81,83 strangely, as AML incidence is higher in males.83 This appears to be specific for NPM1 mutations, as a similar association is not seen for FLT3-ITD,83 which is also common in AML-NK. To date, only the 5q syndrome has been identified as a prevalent genetic alteration in females.118 Therefore, sex-specific differences might underlie the mechanism of NPMc+ AML development.

Clinical impact of NPM1 mutations

Analysis of mutated/cytoplasmic NPM has important clinical applications.

Response to therapy and prognostic value of NPM1 mutations

After induction therapy, AML-NK carrying mutated/cytoplasmic NPM shows a higher complete remission rate than AML-NK without NPM1 mutations.18,80,83,93 Dohner et al81 found NPM1 mutation status is not an independent predictor for responsiveness to chemotherapy, because the best complete remission rate was observed only in the NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD–negative group, while the lowest response rate occurred in AML patients carrying both mutations.

In 4 large European studies80-83 on more than 1000 AML-NKs, NPM1 mutations in the absence of FLT3-ITD identified a subgroup of patients with favorable prognosis. Notably, younger AML patients81 carrying NPM1 mutations without concomitant FLT3-ITD showed approximately 60% probability of survival at 5 years, that is, similar to long-term outcomes in AML carrying core-binding factor (CBF)119,120 or AML-NK with CEBPA mutations.121 In a donor versus no-donor comparison, the favorable prognostic group of NPM-mutated/FLT3-ITD–negative patients did not benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplantation.81

Thus, 2 “dueling” mutations122 act in AML-NK, because NPM1 and FLT3-ITD are, respectively, associated with good and bad prognosis. In patients with both mutations, FLT3-ITD–induced antiapoptotic and proproliferative pathways, especially via STAT5, might dominate the leukemic phenotype,123 explaining why 2 other groups,93,94 which did not stratify patients according to NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutations, could not document differences in survival in NPM1-mutated cases. These studies emphasize the value of comprehensive molecular genetic screening in AML-NK, so as to improve risk stratification.

It is unclear why NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD–negative patients respond reasonably well to therapy. Nucleoplasmic and cytoplasmic recruitment of NPMwt mediated by the NPM mutants might interfere with its functions. NPMwt protects hematopoietic cells from p53-induced apoptosis in conditions of cellular stress124 ; the level of genotoxic stress appears to regulate this effect.56 It is tempting to speculate that NPM mutants fail to protect cells and render them more susceptible to chemotherapy-induced high-level genotoxic stress. Of interest, daunorubicin-induced dislocation of NPMwt into nucleoplasm is associated with increased apoptosis.125

Monitoring of minimal residual disease

Monitoring of minimal residual disease in AML-NK is hampered by the lack of reliable molecular markers. FLT3-ITD can be used for this purpose,11 but is detected in only about 30% of AML-NK.11,12 Since NPM1 mutations appear more stable than FLT3-ITD over the course of disease90,93 and occur in 50% to 60% of AML-NK,18,80-83 they may become a new tool for monitoring minimal residual disease. Preliminary results using a highly-sensitive real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay126 are encouraging but need to be validated in large clinical trials.

Classification of leukemias

Identification of NPMc+ AML impacts on the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AML,2 which encompasses 4 major categories: (1) AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities; (2) AML with multilineage dysplasia; (3) therapy-related AML; and (4) AML “not otherwise characterized.” The latter bin category (currently subclassified according to slightly modified FAB criteria) accounts for 60% to 70% of de novo adult AML, including AML-NK and, therefore, NPMc+ AML. Our observation that the wide morphologic spectrum of NPMc+ AML derives from various combinations, at diverse ratios, of NPMc+ cells of different lineages (all belonging to the leukemic clone)89 question the value of FAB criteria for subclassifying “AML not otherwise characterized.” The frequent finding of multilineage dysplasia in NPMc+ AML89 also raises doubts as to whether dysplasia is a reproducible criterion for assigning a case to WHO category 3. When updating WHO classification, we propose the term “AML not otherwise characterized” should be restricted to AML for which no genetic lesions have as yet been identified, and NPMc+ AML be provisionally considered as a separate entity, because of its high frequency and distinctive clinical and biologic features. Correct definition of the heterogeneous WHO AML categories 3 and 4 and their prognostic significance will require a more genetically oriented approach, including systematic chromosome banding analyses and screening for the prognostically relevant mutations (FLT3, CEBPA, and NPM1).

Future perspectives

In spite of the remarkable progress achieved in biologic, diagnostic, and clinical characterization of NPM1 mutations since their first identification in early 2005,18 several important issues still remain to be explored. Although multilineage involvement points to derivation from a common myeloid or an earlier progenitor without the ability to differentiate into lymphoid lineages,89 the exact cell of origin of NPMc+ AML remains unknown. How does the NPMc+ AML cell of origin correlate with the recently revised road map for adult blood lineage development?127 In NPMc+ AML, how can we reconcile consistent CD34 negativity with up-regulation of HOX genes involved in stem-cell maintenance?82,128 What are the characteristics of leukemic stem cells in NPMc+ AML? These issues need to be addressed by analyzing flow-sorted progenitor populations and their engraftment potential in mice.

How mutated NPM contributes to leukemogenesis still remains elusive. What we know at present could well be only part of the picture since NPM is an extremely eclectic molecule that is involved in multiple functions; others could well be identified in the future. Analysis of rare mutations occurring in NPM1 exons other than 1295,96 and the close relationship between tryptophan mutations and type of NES motif at NPM mutants C-terminus105 suggest the main aim of mutations is to place NPM in cytoplasm. One might infer that aberrant NPM localization in cytoplasm is, in some way, essential for transforming normal hematopoietic cells into leukemic blasts. Since very low levels of NPMwt (due to shuttling activity) are physiologically present in cytoplasm, the amount of NPM mutant that accumulates in cytoplasm may also be crucial for transforming activity. Thus, the goal of NPM1 mutations appears to be to export mutants into cytoplasm at the maximum efficient dose. Interference of the mutants with key functions of NPMwt and oncosuppressor ARF through their recruitment into cytoplasm may play a role in transforming activity, but one cannot discount that mutant NPM may interfere with the functions of other, as yet unidentified, proteins in the nucleus or cytoplasm. Mass spectrometry analysis may help characterize complexes formed by NPM mutants and these putative partners. The role of mutated NPM in leukemogenesis needs to be addressed in experimental models, which, due to close association of FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutations in clinical practice,18,80-83 will also need to investigate whether FLT3-ITD plays a cooperative role (Figure 7).

The NPM1 gene is an appealing target for therapy. Retargeting NPM from cytoplasm to its physiologic site (eg, nucleolus) is challenging because the NES motif and mutated tryptophan(s) at the NPM mutant C-terminus constitute 2 obvious obstacles.105 Analysis of differences in the 3-dimensional structure of the C-terminus of NPM mutants and NPMwt may lead to designing small molecules that can interfere with the abnormal NPM mutant traffic. However, efforts to pharmacologically target NPM might be hindered by the need to tread a very fine line in regulating its function so as to prevent the detrimental consequences of underfunctioning or overfunctioning. In fact, according to expression levels and gene dosage, NPM1 functions both as oncogene and tumor-suppressor gene114 and partial functional loss and aberrant overexpression both lead, through separate mechanisms, to abnormal cell growth.

Several clinical issues yet need to be addressed. Immunohistochemistry (detection of cytoplasmic NPM) should be integrated with cytogenetics/fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)/molecular studies, to achieve maximum rationalization of biologic investigations in AML.84 As NPM1 mutations without FLT3-ITD identify a good prognostic subgroup, mutational studies should, in the future, be used to stratify risk in the heterogeneous category of AML-NK.18,80-83,129 Linking NPM1 mutations to good prognosis raises other clinically important questions. Does the prognostic value of mutated NPM1 apply to AML patients older than 60 years who are recognized as a poor prognostic category? Should adult NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD–negative AML-NK patients be exempted from allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first-line therapy,130 as is current practice for AMLs carrying t(8;21) or Inv(16)? Can we exploit FLT3 inhibitors to reverse NPM1-mutated/FLT3-ITD–positive patients into the more prognostically favorable category of NPM1 mutated/FLT3-ITD negative? Which molecular mechanism underlies the sensitivity of NPMc+ AML to chemotherapy? Does NPMc+ AML show selective sensitivity to any known chemotherapeutic agents? Can we exploit quantitative detection of NPM1-mutated copies126 to predict patients with long-term survival? Future prospective clinical trials and availability of a human cell line (OCI-AML3) carrying cytoplasmic/mutated NPM131 for drug testing should help provide answers.

Authorship

Contribution: B.F. had the original idea, which, inspired by his immunohistochemical studies on ALK-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, led to the discovery of NPM cytoplasmic/mutated acute myeloid leukemia (NPMc+ AML); B.F. is also the head of the project on NPM in acute myeloid leukemia; I.N. carried out the confocal microscopy studies; M.F.M. analyzed clinical data of NPMc+ AML patients; C.M. was involved in the study of NPM1 mutations. All authors contributed to writing the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.F. and C.M. applied for a patent on clinical use of NPM mutants and have a financial interest in the patent.

Correspondence: Brunangelo Falini, Institute of Hematology, Policlinico, Monteluce, 06122 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: faliniem@unipg.it; Cristina Mecucci, Institute of Hematology, Policlinico, Monteluce, 06122 Perugia, Italy; e-mail: crimecux@unipg.it.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC).

We are indebted to Niccolò Bolli, Maria Paola Martelli, Arcangelo Liso, Roberto Rosati, Paolo Gorello, Barbara Bigerna, Alessandra Pucciarini, Roberta, Pacini, Alessia Tabarrini, and Roberta Mannucci for generating some of the data described in the paper. We would also like to thank Claudia Tibidò for her excellent secretarial assistance and Dr Geraldine Anne Boyd for her help in editing this paper.

![Figure 5. Cytoplasmic NPM and multilineage involvement in NPMc+ AML. (Top, left) Myeloid sarcoma (skin, paraffin section). Nuclear plus aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in leukemic blasts. Normal residual vessel endothelial cells show the expected nucleus-restricted NPM expression (arrow). Immunostaining with monoclonal antibody 376 that recognizes both wild-type and mutated NPM (alkaline phosphatase anti–alkaline phosphatase [APAAP] technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlanApo 40×0.85 NA objective). (Top, right) NPMc+ AML (bone marrow biopsy, paraffin section). Cytoplasmic-restricted expression of mutant NPM protein in leukemic cells (arrow). A normal residual megakaryocyte is negative (double arrows). Immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody (Sil-A) that recognizes mutated but not wild-type NPM (APAAP technique; hematoxylin counterstaining; image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective). (Bottom, left) NPMc+ AML with multilineage involvement (bone marrow biopsy, image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UplanApo 40×/0.85 NA objective). Double APAAP/immunoperoxidase staining for NPM (blue) and glycophorin (brown). Aberrant cytoplasmic expression of NPM is seen in proerythroblasts (arrow), megakaryocytes (double arrows), and myeloid blasts surrounding a blood vessel (asterisk). (Bottom, right) Higher magnification (image was collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a UPlan FL 100×/1.3 NA oil objective) from a different field of the same case. Proerythroblasts are strongly NPMc+ (blue) and weakly positive or negative for glycophorin (brown) (long arrow), while more mature erythroid precursors show nucleus-restricted NPM(blue)/strong surface glycophorin (brown) (short arrow). Double arrows indicate a NPMc+/glycophorin-negative megakaryocyte. A myeloid blast is positive for cytoplasmic NPM (blue) and negative for surface glycophorin (arrowhead).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/3/10.1182_blood-2006-07-012252/5/m_zh80030707100005.jpeg?Expires=1764978970&Signature=bgQWU-KBPMAXqfF3OpuB9nebkBnRXzEjmiBw85jumAKsDmh6uWk8CXdFMhVeenNrsfNmYlrZZ3Un~8Nd8gmXh2n4BKZfiaWWuE82NvculRAoTKwUYDdzDKy2WrgKLgQxARZLNeACoGJftFQtQNBKBskcHJ02DRcblRGpfYdVOD9Lh0kL4nkgnCHZJPyA5nW3WahXLqs2z6mvJmA5INVjLkSkKcOuCfPldOEyRNMpttkDH7~jZqt6KWdgpPR~XqXniL3RWzF7GZQrtAnrtb-AOaJpiRI9kkzwxhsitN6OZc9n-BTbC48IJmBxXXbmDk5QcfaUsYBmnzhB~0YsemvwPg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal