Abstract

During inflammation, monocytes roll on activated endothelium and arrest after stimulation by proteoglycan-bound chemokines and other chemoattractants. We investigated signaling pathways downstream of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are relevant to α4β1 integrin affinity up-regulation using formyl peptide receptor-transfected U937 cells stimulated with fMLP or stromal-derived factor-1α and human peripheral blood monocytes stimulated with multiple chemokines or chemoattractants. The up-regulation of soluble LDV peptide or vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) binding by these stimuli was critically dependent on activation of phospholipase C (PLC), inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors, increased intracellular calcium, influx of extracellular calcium, and calmodulin, suggesting that this signaling pathway is required for α4 integrins to assume a high-affinity conformation. In fact, a rise in intracellular calcium following treatment with thapsigargin or ionomycin was sufficient to induce binding of ligand. Blockade of p44/42 and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, or protein kinase C (PKC) signaling did not inhibit chemoattractant-induced LDV or VCAM-1 binding. However, activation of PKC by phorbol ester up-regulated α4β1 affinity with kinetics distinct from those of GPCR signaling. A critical role for PLC and calmodulin was also established for leukocyte arrest and adhesion strengthening.

Introduction

During emigration, integrin activation by chemoattractants or chemokines is a key step resulting in the arrest of rolling leukocytes.1,2 This activation step results in the recruitment of specific leukocytes from the blood and is important for both inflammatory and homeostatic physiology. Two models have been proposed to explain integrin activation: affinity and valency.3,4 Alterations in integrin conformation can increase the intrinsic affinity of each molecule for its cognate ligands and result in stable or persistent binding.5,6 Binding of monomeric soluble ligand is dependent on individual integrin-ligand interactions and can be used to assess integrin affinity.7 Thus far, several integrins in the β1, β2, β3, and β7 families have been shown to modulate their affinity in response to inside-out signals. 8-10 In contrast, the ability of a cell to increase the number of cotemporaneous integrin-ligand bonds is multivalent ligand binding.11 This can be the result of increased integrin lateral mobility in the plasma membrane or clustering and cannot be detected by soluble monomeric ligand. In this model, lateral mobility of integrins within the plasma membrane directly correlates with increased cell-substrate adhesion.12,13 It is unlikely that these 2 modes of modulating integrin-ligand binding are mutually exclusive, and indeed they may be interdependent,14 because studies suggest that integrin microclustering is dependent on affinity up-regulation and ligand binding.15

Studies have indicated that rapid up-regulation of α4β1 and αLβ2 integrin affinity is required for monocyte arrest on vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and T-lymphocyte arrest on intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), respectively,16-18 although multivalent binding also may be involved.17,19 Signaling molecules downstream of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are involved in the up-regulation of integrin affinity by chemoattractants and chemokines remain unclear. Previous studies have evaluated the role of signaling pathways in the adhesion and/or migration of different leukocyte types involving various integrins. However, cell adhesion and migration can involve changes in integrin affinity, valency of binding, as well as major remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, each of which may involve distinct or overlapping signaling molecules. A direct evaluation of individual signaling pathways in the regulation of α4β1 integrin affinity has not been described.

Conflicting results regarding the role of individual signaling pathways in leukocyte adhesion have been described depending on the assay and the stimulus used. For example, inhibition of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)–blocked T-cell adhesion but not binding of soluble fibronectin or HUTS-21 antibody,20 and PI3K and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) were implicated in the migration or arrest of myeloid cells.21,22 However, in another study, stromal cell–derived factor-1α (SDF-1)–stimulated tethering and arrest of peripheral blood T cells on VCAM-1 was independent of PI3K.19 Thus, although various signaling pathways have been implicated, in many instances it is not clear how they modulate integrin function and how this relates to a biologic response such as adhesion.

We investigated the proximal intracellular signaling pathways initiated by chemoattractant and chemokine GPCRs that are involved in regulating monocyte α4 integrin affinity. This is a very rapid and transient response that is relevant to the arrest of rolling leukocytes on activated endothelium. Stimulation of GPCR induced binding of LDV peptide and VCAM-1 and leukocyte arrest, which were critically dependent on the activation of phospholipase C (PLC), influx of extracellular calcium, and activation of calmodulin.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The myelomonocytic U937 cell line transfected with human formyl peptide receptor (U937-FPR) was obtained from Dr Gregory P. Downey (University of Toronto).16 Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 500 μg/mL geneticin.

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were purchased from Clonetics (East Rutherford, NJ). HAECs were grown in Endothelial Cell Medium-2 supplemented with 5% FBS, hydrocortisone, vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, heparin, epidermal growth factor, gentamicin, amphotericin B, R3-IGF-1, and ascorbic acid (Clonetics). HAECs were grown to confluence in tissue culture flasks (Corning, Corning, NY), passaged every 4 to 5 days and used for experiments between the third and sixth passage.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. Collection of blood samples from human volunteers was approved by the Research Ethics Board at University Health Network. Briefly, venous blood anticoagulated with heparin was obtained from healthy volunteers, a buffy coat was collected and layered over Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and mononuclear leukocytes were separated by centrifugation at 300g for 20 minutes. Monocytes were purified from PBMCs by negative depletion using a magnetic particle kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and used immediately. The purity of monocytes was determined by immunostaining for CD14 and analysis of forward and side scatter. Viability was determined by propidium iodide exclusion, and activation status was monitored by L-selectin shedding. Samples were used if purity was greater than 90%, and L-selectin shedding was not detected.

Inhibitors

Leukocytes were incubated with the following inhibitors at 37°C for 30 minutes unless otherwise indicated: U0126 (10 μM) and LY294002 (20-50 μM) from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA); U73122 (300-1000 nM) and 2-APB (3-100 μM) from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); GF109203X (1 μM), SB203580 (10 μM), wortmannin (100 nm), W7 (10-100 nM), and SKF96365 (100 μM) from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA); BAPTA-AM (12 μM) from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR); PTx (100 ng/mL, 6 hours) or vehicle control (DMSO) from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Ligand-binding assays

Real-time LDV-FITC binding assay.

FITC-conjugated peptide 4-((N′-2-methylphenyl)ureido)-phenylacetyl-l-leucyl-l-α-aspartyl-l-valyl-l-prolyl-l-alanyl-l-alanyl-l-lysine (LDV-FITC)23 was synthesized by Commonwealth Biotechnologies (Richmond, VA). LDV-FITC binding was determined in real time using a Coulter EPICS-XL (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL), as previously described.23 Leukocytes at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/mL in HBSS (with 1 mM Ca2+/Mg2+) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) and 0.5% FBS (assay buffer) were pretreated with inhibitors as indicated in individual experiments. Leukocytes were preincubated with LDV-FITC (3 nM) for 15 minutes. Basal binding of LDV-FITC was measured for 30 to 60 seconds prior to sample removal, addition of stimulus, and resumption of data acquisition within 5 to 10 seconds. Dead cells were omitted by gating out cells that stained with propidium iodide. Mean channel fluorescence was calculated at each time interval. LDV-FITC fluorescence in the presence of 5 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) was used as a negative control and was subtracted from each treatment.

Soluble ligand–binding assay.

Recombinant human VCAM-1 monomers were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and human VCAM-1/Fc chimeric protein was provided by Dr D. Staunton (ICOS, Bothwell, WA).24 U937-FPR cells pretreated with pharmacologic inhibitors were suspended at 1 × 107/mL in assay buffer and incubated with VCAM-1 (20 μg/mL), VCAM-1/Fc (20 μg/mL), or LDV-FITC (3 nM) for 15 min-utes at 22°C prior to stimulation with Mn2+ (1 mM, 5 minutes) or fMLP (100 nM, 1-20 minutes). At appropriate time points, 100-μL aliquots were removed, diluted with 1 mL HBSS, and fixed by adding 1 mL 2% paraformaldehyde at 22°C. Cells were washed with HBSS, and bound ligand was detected using anti–human VCAM-1 (Hu8/4 tissue culture supernatant generated by minimum inhibitory concentration [M.I.C.]) followed by fluorochrome-conjugated anti–mouse IgG or biotin-conjugated anti-FITC followed by streptavidin-fluorochrome (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Intracellular signaling assays

Measurement of intracellular free Ca2+.

Intracellular free Ca2+ was measured fluorometrically with Fura-2 (Molecular Probes) loaded leukocytes as previously described.25 Ratio fluorescence was monitored using a Delta-RAM dual wavelength illumination and recording system from Photon Technology International (Birmingham, NJ) (excitation 340/380 nm; emission 510 nm), driven by Felix software (Photon Technology International).

Measurement of intracellular pH.

Intracellular pH was determined fluorometrically in 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-AM (BCFEF; Molecular Probes) loaded cells as previously described.25 Ratio fluorescence was continuously monitored using excitation at 440/490 nm and emission at 510 nm.

Calcium analysis by flow cytometry.

Fluo-3 (Molecular Probes) fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described.26 Data are expressed as mean channel fluorescence.

Parallel plate flow chamber assays

VCAM-1/Fc and SDF-1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) were immobilized to 35-mm polystyrene tissue culture dishes as previously described.16 Briefly, goat anti–human IgG F(ab′)2 was incubated at 10 μg/mL (60 minutes at 22°C) followed by SDF-1 at 20 μg/mL (120 minutes at 22°C). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% FBS, and the coated area was incubated with VCAM-1/Fc at 5 μg/mL for 60 minutes. The density of VCAM-1/Fc was determined using I125-human IgG as a human Fc-containing protein. The anti–Fc-coated surface supported a maximum density of 272 Fc-containing molecules/mm2 (544 VCAM-1 molecules, because VCAM-1 is a dimer in VCAM-1/Fc). The density of immobilized VCAM-1/Fc was modulated in some experiments using an equal volume of equimolar human IgG and VCAM-1/Fc to attain 50% coating density of VCAM-1.

HAECs were grown to confluence on gelatin (2%)–pretreated 35-mm tissue culture dishes. IL-1β (30 U/mL) was added to the culture media 24 hours prior to experiments and removed by washing 3 times. Where indicated, confluent monolayers were superfused and incubated for 10 minutes with SDF-1 (100 ng/mL), prior to infusion of leukocytes.

Leukocyte arrest and detachment assays were performed using parallel plate flow chambers (Glycotech, Rockville, MD) as previously described.16 Adhesion molecule–coated dishes or confluent HAEC monolayers served as the bottom surface, and a silicone gasket formed a 0.254-mm high and 2.5-mm wide flow path. Flow chambers were maintained at 37°C with an infrared heat lamp. Cells were observed with a Diaphot 300 inverted phase-contrast microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY), recorded with a Sony (San Diego, CA) DXC-151A video camera and Sony SVT-S3100 time-lapse video cassette recorder and analyzed offline using Scion Image 4.0.2 (Scion, Frederick, MD).

For arrest assays, U937-FPR cells in assay buffer were infused with a programmable syringe pump (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) at a wall shear stress of 1.0 to 1.25 dyne/cm2. The number of arrested leukocytes (stationary for > 5 seconds) was determined in 6 nonoverlapping high-power fields after 2 minutes of flow. It was unusual for arrested cells to release subsequently.

For detachment assays U937-FPR cells were injected via the outflow port into inverted flow chambers and allowed to settle for 2 minutes under static conditions once overturned. Following static adhesion, shear stress of 2, 4, 10, and 20 dynes/cm2 was applied by pulling assay buffer through chambers with a programmable syringe pump with shear stress increasing at 20-second intervals. The number of cells remaining attached after each interval was expressed as a percentage of input cells.

Results

PLC, but not p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK, or PI3K, is critical for chemoattractant-induced up-regulation of LDV peptide binding by α4 integrins

Stimulation of leukocytes by chemokines or chemoattractants induces a rapid and transient increase in α4 integrin affinity that can be detected by soluble ligand binding.16,23 We used flow cytometry to monitor α4 integrin affinity in real time using a modified fluorescent peptide, LDV-FITC, which contains the minimal consensus binding sequence for α4 integrin.23 Like monocytes, U937-FPR cells have low basal α4 integrin affinity, which can be up-regulated by either fMLP or SDF-1.16,23 Prior to stimulation, LDV-FITC binding to U937-FPR cells was low (Figure 1A). Binding increased following treatment with 0.5 mM Mn2+, a positive control that increases α4 integrin affinity for ligand by association with divalent cation binding sites.27,28 Treatment with either fMLP or SDF-1 resulted in a rapid increase in LDV-FITC binding (Figure 1A), indicative of inside-out signaling that increases α4 integrin affinity. Similar responses were observed over broad dose ranges and were maximal at 100 nM fMLP and 12.5 nM SDF-1 (Figure 1A). U937-FPR cells did not respond to other chemokines, including MCP-1 and SLC (J.R.C., unpublished data, August 2002). fMLP- and SDF-1–induced responses were dependent on G protein–signaling pathways, because they were completely inhibited by pertussis toxin.16

Inhibition of PLC abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding in U937-FPR cells. (A) Flow cytometry was used to determine LDV-FITC binding in real time to U937-FPR cells stimulated with 0.5 mM Mn2+, fMLP, SDF-1, or buffer (at time 0). One of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Free intracellular calcium levels were measured by fluorimetry in Fura2-loaded U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO or U73122 and stimulated with fMLP (100 nM), SDF-1 (12.5 nM), thapsigargin (1 μM), or buffer. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. A U73122 dose response is shown in the right panel. Data are expressed as ratios of the peak fMLP-induced calcium flux in cells treated with varying concentrations of U73122 relative to DMSO-treated cells. (C) Flow cytometry was used to determine LDV-FITC binding in real time to U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO (0.1%, vehicle control) or U73122 prior to addition of fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or buffer at time 0. One of at least 4 independent experiments is shown.

Inhibition of PLC abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding in U937-FPR cells. (A) Flow cytometry was used to determine LDV-FITC binding in real time to U937-FPR cells stimulated with 0.5 mM Mn2+, fMLP, SDF-1, or buffer (at time 0). One of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Free intracellular calcium levels were measured by fluorimetry in Fura2-loaded U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO or U73122 and stimulated with fMLP (100 nM), SDF-1 (12.5 nM), thapsigargin (1 μM), or buffer. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. A U73122 dose response is shown in the right panel. Data are expressed as ratios of the peak fMLP-induced calcium flux in cells treated with varying concentrations of U73122 relative to DMSO-treated cells. (C) Flow cytometry was used to determine LDV-FITC binding in real time to U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO (0.1%, vehicle control) or U73122 prior to addition of fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or buffer at time 0. One of at least 4 independent experiments is shown.

Treatment of U937 cells with fMLP and SDF-1 induced a rapid activation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK pathways, determined by Western blotting for phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK and MAPKAP2, respectively. These experiments also demonstrated complete inhibition of the respective MAPK pathways by U0126 (Figure S1A, available at the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) or PD98059 (S.J.H., unpublished data, November 2002) and SB203580 (Figure S1A). Inhibition of either MAPK pathway did not attenuate fMLP-, SDF-1–, or Mn2+-induced LDV-FITC binding (Figure S1B).

PI3K signaling was also rapidly activated by treatment of U937 cells with fMLP and SDF-1 and was inhibited by LY294002 and wortmannin, as was determined by Western blotting for phospho-AKT, a kinase downstream of PI3K (Figure S1C). LY294002 did not inhibit either fMLP- or SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding, whereas wortmannin decreased SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding slightly and fMLP-stimulated binding returned to baseline more rapidly (Figure S1D).

Treatment of U937 cells with fMLP or SDF-1 resulted in a very rapid and transient increase in [Ca2+]i when compared with thapsigargin (Sigma), an inhibitor of SERCA pumps, that caused a gradual and prolonged increase (Figure 1B). U73122, an inhibitor of PLC, blocked the fMLP-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (Figure 1B) but had no effect on the response to thapsigargin (J.R.C. and M.H., unpublished data, December 2002). U73122 also inhibited fMLP-induced LDV-FITC binding in a dose-dependent fashion and at 1 μM completely abrogated both fMLP- and SDF-1–stimulated binding of LDV-FITC (Figure 1C). As expected, U73122 did not affect Mn2+-induced LDV-FITC binding.

IP3, but not PKC, is a mediator of chemoattractant-induced LDV binding

PLC catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG).29 Binding of IP3 to its receptor on the endoplasmic reticulum results in release of calcium from intracellular stores,30 whereas DAG can activate both conventional and novel isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC).31 To determine which of these pathways may be involved in the regulation of α4 integrin affinity, U937-FPR cells were pretreated with 2-APB, an inhibitor of IP3 receptor–mediated calcium release, or GF109203X, a PKC inhibitor. In the presence of 2-APB, there was a dose-dependent reduction of both [Ca2+]i flux and LDV-FITC fluorescence in response to fMLP (Figure 2A). stimulated LDV-FITC binding was also inhibited by 2-APB, but Mn2+-induced binding was unaffected. Regulation of α4 integrin affinity by PMA-induced activation of PKC has been described.32 PMA (Sigma) induced a gradual increase in LDV-FITC binding that persisted at 20 minutes (Figure 2B) and at 60 minutes (not shown). In contrast, LDV-FITC binding induced by GPCR signaling was transient and returned to baseline levels by 20 minutes (Figure 2B). Inhibition of PKC by GF109203X, overnight incubation with PMA (Figure 2B), or chelerythrine chloride (J.R.C., unpublished data, November 2002) abrogated PMA-induced, but not fMLP-induced, LDV-FITC binding.

Inhibition of IP3, but not PKC, abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. (A) LDV-FITC binding to U937-FPR cells pretreated with 2-APB and stimulated at time 0 with fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or buffer was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. Dose responses for inhibition of fMLP-induced peak intracellular calcium flux (determined by fluorimetry) and LDV-FITC binding by 2-APB are shown. (B) U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO (0.1%, 30 minutes), GFX109203X (1 μM, 30 minutes), or PMA (50 nM, 18 hours) were stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, fMLP, or PMA, and LDV-FITC binding was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Inhibition of IP3, but not PKC, abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. (A) LDV-FITC binding to U937-FPR cells pretreated with 2-APB and stimulated at time 0 with fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or buffer was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. Dose responses for inhibition of fMLP-induced peak intracellular calcium flux (determined by fluorimetry) and LDV-FITC binding by 2-APB are shown. (B) U937-FPR cells pretreated with DMSO (0.1%, 30 minutes), GFX109203X (1 μM, 30 minutes), or PMA (50 nM, 18 hours) were stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, fMLP, or PMA, and LDV-FITC binding was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Role of intracellular and extracellular calcium

Stimulation of U937-FPR cells with either fMLP or SDF-1 triggered an increase in [Ca2+]i that was inhibited by pertussis toxin and thus dependent on Gαi-coupled signaling (J.R.C., unpublished data, March 2001) and could be inhibited by chelating [Ca2+]i with BAPTA (Figure 3A) Chelation of intracellular calcium with BAPTA also inhibited fMLP- and SDF-1–induced, but not Mn2+-induced, LDV-FITC binding (Figure 3B). A typical response to fMLP in BAPTA-loaded cells consisted of a gradual, relatively slow and markedly blunted increase in LDV-FITC binding. Responses to SDF-1 were below the detection limit in BAPTA-loaded cells. Treatment with thapsigargin induced a gradual increase in [Ca2+]i, as well as LDV-FITC binding, both of which were inhibited by BAPTA. Stimulation of U937 cells with ionomycin (Sigma) induced a rapid and relatively large increase in [Ca2+]i (not shown) and a dose-dependent increase in LDV-FITC binding that was maximal at 1 μM but lower in magnitude than the fMLP-induced response (Figure 3C). Calcium released from intracellular stores can open calcium-permeable plasma membrane channels, leading to an influx of extracellular calcium. Measurement of cytosolic calcium in individual U937-FPR cells following stimulation with fMLP or SDF-1 revealed a biphasic increase in [Ca2+]i, and inhibition of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels with SKF96365 produced [Ca2+]i fluxes with a shorter duration that were similar to those when extracellular calcium was chelated with EGTA (Figure 3D). The opening of plasma membrane channels following stimulation with fMLP was verified by adding Mn2+ to the assay buffer, which quenched Fura-2 fluorescence signals (J.R.C., unpublished data, June 2001). Pretreatment of U937-FPR cells with SKF96365 (Figure 3E) resulted in complete inhibition of both fMLP- and SDF-1–stimulated LDV-FITC binding, suggesting that an influx of extracellular calcium is a necessary step in α4 integrin affinity up-regulation. Replacing Ca2+ in the assay buffer with Mg2+-reconstituted basal LDV-FITC binding (Figure 3F, left), yet under assay conditions of 1 mM Mg2+, stimulation with fMLP or SDF-1 did not increase LDV-FITC binding (Figure 3F, right). Inhibition of fMLP and SDF-1–stimulated LDV-FITC binding was also observed when the calcium concentration in the assay buffer was clamped at 100 nM by EGTA (J.R.C., unpublished data, May 2001). These data indicate that an influx of extracellular calcium is required for up-regulation of α4 integrin affinity by fMLP and SDF-1.

Role of intracellular and extracellular calcium in fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. U937-FPR cells pretreated with either DMSO (0.1%, 30 minutes) or BAPTA-AM (12 μM, 30 minutes) were stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, thapsigargin (Tg; 1 μM), fMLP, or SDF-1. Intracellular calcium levels (Fluo-3 fluorescence; A) and LDV-FITC binding (B) were analyzed in real time by flow cytometry. One of 4 independent experiments is shown. (C) Illustrates LDV-FITC binding induced by ionomycin (0.1 and 1 μM) compared with Mn2+, fMLP, and buffer control. (D) Single-cell calcium imaging of Fura-2–loaded U937-FPR cells stimulated with fMLP in the presence of DMSO (control), SKF96365 (100 μM), or EGTA (5 mM). (E) LDV-FITC binding to U937-FPR cells pretreated with SKF96365 prior to stimulation (arrow) with fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or thapsigargin. One of 4 independent experiments is shown. (F) Basal LDV-FITC binding (mean ± SEM) to U937-FPR cells in assay buffer containing the indicated concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ (left). U937-FPR cells were stimulated (arrow) with fMLP, SDF-1, or Mn2+ and analyzed for LDV-FITC binding in a calcium-free assay buffer containing 1 mM Mg2+ (right). One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Role of intracellular and extracellular calcium in fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. U937-FPR cells pretreated with either DMSO (0.1%, 30 minutes) or BAPTA-AM (12 μM, 30 minutes) were stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, thapsigargin (Tg; 1 μM), fMLP, or SDF-1. Intracellular calcium levels (Fluo-3 fluorescence; A) and LDV-FITC binding (B) were analyzed in real time by flow cytometry. One of 4 independent experiments is shown. (C) Illustrates LDV-FITC binding induced by ionomycin (0.1 and 1 μM) compared with Mn2+, fMLP, and buffer control. (D) Single-cell calcium imaging of Fura-2–loaded U937-FPR cells stimulated with fMLP in the presence of DMSO (control), SKF96365 (100 μM), or EGTA (5 mM). (E) LDV-FITC binding to U937-FPR cells pretreated with SKF96365 prior to stimulation (arrow) with fMLP, SDF-1, Mn2+, or thapsigargin. One of 4 independent experiments is shown. (F) Basal LDV-FITC binding (mean ± SEM) to U937-FPR cells in assay buffer containing the indicated concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ (left). U937-FPR cells were stimulated (arrow) with fMLP, SDF-1, or Mn2+ and analyzed for LDV-FITC binding in a calcium-free assay buffer containing 1 mM Mg2+ (right). One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Calmodulin-dependent processes regulate LDV binding

Calmodulin is a relatively small protein that binds 4 calcium ions, resulting in marked changes in its conformation that enable it to bind and influence the function of a large number of proteins.33 Because calmodulin senses intracellular calcium levels and relays signals to various enzymes, ion channels and other proteins, we investigated whether calmodulin is relevant to GPCR-induced LDV binding. Treatment of U937-FPR cells with W7, an inhibitor of calmodulin, blocked fMLP- and SDF-1–induced increases in LDV-FITC binding (Figure 4A) but had no effect on Mn2+-induced binding. Optimal W7 concentration was determined by performing dose-response experiments that assessed calmodulin-dependent activation of the sodium-hydrogen pump (Figure 4B). Treatment of U937 cells with ionomycin caused a drop in intracellular pH that gradually recovered. The recovery of intracellular pH was dependent on the sodium-hydrogen pump, as was demonstrated by pretreatment of cells with amiloride, an inhibitor of Na+/H+ exchange. Inhibition of calmodulin by W7 also inhibited the recovery of intracellular pH in a dose-dependent fashion. Other inhibitors of calmodulin, including TFP were used to confirm the specificity of W7 action (J.R.C., unpublished data, October 2002).

Inhibition of calmodulin abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. (A) U937-FPR cells were pretreated with DMSO or W7 and stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, fMLP, or SDF-1. LDV-FITC binding was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Ionomycin-induced pH changes in BCECF-loaded U937-FPR cells were determined using a fluorometer. Cells were pretreated with DMSO, ethylisopropyl amiloride (EIPA; 10 μM), a Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor, or W7 and stimulated with ionomycin at time 0.

Inhibition of calmodulin abrogates fMLP- and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding. (A) U937-FPR cells were pretreated with DMSO or W7 and stimulated at time 0 with Mn2+, buffer, fMLP, or SDF-1. LDV-FITC binding was analyzed in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) Ionomycin-induced pH changes in BCECF-loaded U937-FPR cells were determined using a fluorometer. Cells were pretreated with DMSO, ethylisopropyl amiloride (EIPA; 10 μM), a Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor, or W7 and stimulated with ionomycin at time 0.

Regulation of LDV-FITC binding in human peripheral blood monocytes

To test whether our observations with U937-FPR cells were relevant to primary human leukocytes, we isolated peripheral blood monocytes and stimulated them with fMLP, SDF-1, or RANTES in the presence of pharmacologic inhibitors. Both fMLP and SDF-1 up-regulated LDV-FITC binding with kinetics similar to U937-FPR cells (Figure 5), and blockade of phospholipase C and intracellular calcium inhibited both fMLP and SDF-1–stimulated LDV-FITC binding, consistent with U937-FPR cells. Neither the inhibition of p44/42 MAPK nor PI3K had a significant effect on induced LDV-FITC binding. We also tested the capacity of various chemokines and chemoattractants to up-regulate the affinity of peripheral blood monocyte α4 integrins. These stimuli induced rapid and transient increases in LDV-FITC binding (Table S1). Even ATP, which is not chemotactic for monocytes, but induces a [Ca2+]i flux through activation of purinergic receptors, up-regulated LDV-FITC binding. This suggests that LDV-peptide binding to monocyte α4 integrin can be induced by multiple stimuli that trigger a flux in [Ca2+]i.

Inhibition of PLC and calcium, but not p44/42 MAPK or PI3K, abrogates RANTES-, fMLP-, and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding to human peripheral blood monocytes. Purified blood monocytes were pretreated with DMSO, U0126 (10 μM), wortmannin (100 nM), U73122 (1 μM), BAPTA-AM (12 μM), or SKF96365 (100 μM) and then stimulated with RANTES (12.5 nM), fMLP (100 nM), or SDF-1 (12.5 nM). LDV-FITC binding was measured by flow cytometry in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Inhibition of PLC and calcium, but not p44/42 MAPK or PI3K, abrogates RANTES-, fMLP-, and SDF-1–induced LDV-FITC binding to human peripheral blood monocytes. Purified blood monocytes were pretreated with DMSO, U0126 (10 μM), wortmannin (100 nM), U73122 (1 μM), BAPTA-AM (12 μM), or SKF96365 (100 μM) and then stimulated with RANTES (12.5 nM), fMLP (100 nM), or SDF-1 (12.5 nM). LDV-FITC binding was measured by flow cytometry in real time. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Regulation of VCAM-1 binding

A key natural ligand for monocyte α4 integrins is VCAM-1, whose expression is induced on vascular endothelial cells by inflammatory cytokines. To verify whether the signaling pathway identified herein regulates chemoattractant-induced binding of soluble VCAM-1, assays were performed using recombinant human monomeric VCAM-1. Basal VCAM-1 binding to U937-FPR cells was low, but increased 4-fold in the presence of 0.5 mM Mn2+ and 2-fold following a 30-minute treatment with PMA (S.J.H., unpublished data, July 2005). The time course of VCAM-1 binding to fMLP-stimulated cells closely mirrored that of LDV-FITC. Binding increased rapidly, gradually declined after 5 minutes and approached baseline levels by 10 to 20 minutes (Figure 6A) A similar time course and magnitude of stimulation was observed with dimeric VCAM-1/Fc (S.J.H., unpublished data, July 2005).

fMLP-induced binding of VCAM-1 and LDV-FITC to U937-FPR cells is similar. (A) A time course of VCAM-1 monomer binding stimulated with fMLP is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3). Asterisks indicate values that differ significantly (P < .05) from the control (0 time point). (B) The effects of inhibitors on fMLP-induced binding of LDV-FITC, VCAM-1, and VCAM-1/Fc were compared. U937-FPR cells were pretreated with various inhibitors used at the same concentrations as in previous figures or with vehicle. For each ligand and inhibitor, the increase in ligand binding to cells stimulated for 3 minutes with fMLP (100 nM) relative to unstimulated cells was determined, and data were normalized to cells pretreated in parallel with vehicle or buffer.

fMLP-induced binding of VCAM-1 and LDV-FITC to U937-FPR cells is similar. (A) A time course of VCAM-1 monomer binding stimulated with fMLP is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3). Asterisks indicate values that differ significantly (P < .05) from the control (0 time point). (B) The effects of inhibitors on fMLP-induced binding of LDV-FITC, VCAM-1, and VCAM-1/Fc were compared. U937-FPR cells were pretreated with various inhibitors used at the same concentrations as in previous figures or with vehicle. For each ligand and inhibitor, the increase in ligand binding to cells stimulated for 3 minutes with fMLP (100 nM) relative to unstimulated cells was determined, and data were normalized to cells pretreated in parallel with vehicle or buffer.

The same pharmacologic inhibitors that were used to assess LDV-FITC binding in real time were used in the soluble ligand binding assay to directly compare fMLP-induced binding of LDV-FITC, monomeric VCAM-1, and VCAM-1/Fc (Figure 6B). Inhibitors of p44/42 MAPK did not block fMLP-induced binding of any ligand. Inhibition of PLC, IP3 receptors, plasma membrane calcium channels, and calmodulin activation and chelation of intracellular calcium attenuated binding of VCAM-1 and LDV-FITC. Treatment of U937-FPR cells with ionomycin (1 μM) increased VCAM-1 binding by 1.6-fold (unpublished data, August 2005), which is consistent with its effect on LDV-FITC binding (Figure 3).

Leukocyte arrest is dependent on PLC, extracellular calcium entry, and activation of calmodulin

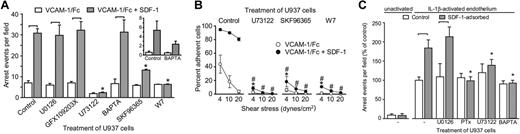

We investigated whether the signaling pathways that regulate α4 integrin affinity participate in chemokine-triggered leukocyte arrest on plates coated with VCAM-1 with or without SDF-1. U937 adhesion in these assays was robust, highly reproducible, and dependent solely on α4 integrins, as was assessed by a function-blocking antibody (S.J.H., unpublished data, August 2005). SDF-1–induced arrest on VCAM-1–coated surfaces is critically dependent on PLC, entry of extracellular calcium, and calmodulin signaling (Figure 7A) In these studies, BAPTA was unable to inhibit arrest at a dose that caused a significant inhibition of α4 integrin affinity modulation. However, on plates coated at 50% VCAM-1 density, BAPTA inhibited SDF-1–induced arrest, which suggests that the residual high-affinity integrins present following BAPTA treatment are mediating arrest at higher densities of VCAM-1 (Figure 7A, inset). The number of interacting cells was not inhibited by any of the pharmacologic inhibitors used. When inhibition of arrest was observed, a concomitant increase in the number of tethering and rolling cells was seen (G.C.D., unpublished data, August 2005). PLC, influx of extracellular calcium, and calmodulin signaling were also essential for monocyte adhesion strengthening on VCAM-1 induced by SDF-1 (Figure 7B). These data indicate that the PLC-calcium-calmodulin signaling pathway induces a conformation in α4 integrins that is critical for arrest on VCAM-1 and mediates the strengthening of monocyte adhesion to VCAM-1.

Leukocyte arrest and adhesion strengthening is critically dependent on PLC, calcium influx, and calmodulin. (A) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were infused at 1 dyne/cm2 into parallel plate flow chambers coated with VCAM-1 ± SDF-1. The number of cells arrested after 2 minutes is shown. Significant differences within groups (± SDF-1) are indicated with brackets (P < .05). U73122, SKF96365, and W7 inhibited the response to SDF-1 (asterisks, P < .05). The inset shows data from assays in which the adhesion surface was coated with VCAM-1 at 50% density. (B) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were allowed to adhere for 2 minutes under static conditions to parallel plate flow chambers coated with VCAM-1 ± SDF prior to the introduction of flow at incrementally increasing shear rates. The percentage of cells remaining attached at each shear rate is shown. U73122, SKF96365, and W7 significantly inhibited adhesion strengthening to VCAM-1 alone (*), or in combination with SDF-1 (#) (P < .05). (C) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were infused for 6 minutes at 1 dyne/cm2 into parallel plate flow chambers containing monolayers of human aortic endothelial cells. Monolayers were unactivated or treated with IL-1β (30 U/mL) for 24 hours. SDF-1 was adsorbed onto some of the monolayers immediately prior to infusion of leukocytes. The number of leukocytes arrested on the endothelial monolayers is shown (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 independent experiments). PTx, U73122, and BAPTA-AM, but not U0126, treatment of U937 cells induced significant differences (asterisks, P < .05) in arrest on monolayers with adsorbed SDF-1.

Leukocyte arrest and adhesion strengthening is critically dependent on PLC, calcium influx, and calmodulin. (A) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were infused at 1 dyne/cm2 into parallel plate flow chambers coated with VCAM-1 ± SDF-1. The number of cells arrested after 2 minutes is shown. Significant differences within groups (± SDF-1) are indicated with brackets (P < .05). U73122, SKF96365, and W7 inhibited the response to SDF-1 (asterisks, P < .05). The inset shows data from assays in which the adhesion surface was coated with VCAM-1 at 50% density. (B) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were allowed to adhere for 2 minutes under static conditions to parallel plate flow chambers coated with VCAM-1 ± SDF prior to the introduction of flow at incrementally increasing shear rates. The percentage of cells remaining attached at each shear rate is shown. U73122, SKF96365, and W7 significantly inhibited adhesion strengthening to VCAM-1 alone (*), or in combination with SDF-1 (#) (P < .05). (C) U937-FPR cells pretreated with the indicated inhibitors were infused for 6 minutes at 1 dyne/cm2 into parallel plate flow chambers containing monolayers of human aortic endothelial cells. Monolayers were unactivated or treated with IL-1β (30 U/mL) for 24 hours. SDF-1 was adsorbed onto some of the monolayers immediately prior to infusion of leukocytes. The number of leukocytes arrested on the endothelial monolayers is shown (mean ± SEM, n ≥ 3 independent experiments). PTx, U73122, and BAPTA-AM, but not U0126, treatment of U937 cells induced significant differences (asterisks, P < .05) in arrest on monolayers with adsorbed SDF-1.

Leukocyte arrest on cytokine-activated human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) was also investigated. HAEC monolayers were treated with IL-1β or TNFα, mounted in parallel plate flow chambers, and superfused with SDF-1 (100 nM) prior to infusion of U937 cells. SDF-1 significantly increased U937 arrest on IL1β- (Figure 7C) or TNFα-activated HAECs (M.D.P., unpublished data, May 2004) but not on unactivated endothelium. SDF-1–induced arrest was attenuated by pertussis toxin, U73122, and BAPTA but not U0126.

Discussion

Binding of ligands to chemokine or chemoattractant receptors activates numerous signal transduction cascades and regulates diverse leukocyte functions, including adhesion, emigration, and chemotaxis.34,35 Numerous signaling events contribute to leukocyte adhesion and migration through the regulation of integrin function, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and cell motility. During emigration from blood into tissues, leukocyte integrins must be rapidly activated to mediate arrest,36 and this process is largely regulated by chemokine signaling through GPCRs. The contribution of integrin affinity and valency modulation to chemokine-induced arrest is not clear. We and others have demonstrated that high-affinity integrins contribute to arrest under flow.16,17,37 The contribution of individual signaling pathways to the rapid up-regulation of integrin affinity by chemoattractants and chemokines has not been elucidated and was the focus of the current study.

PI3K, p44/42 MAPK, and p38 MAPK appear to play an important role in leukocyte chemotaxis. Neutrophils from PI3Kγ-deficient mice have impaired chemotactic responses to fMLP, C5a, and IL-8.38 Similarly, SDF-1–induced activation of PI3K and p44/42 MAPK regulates chemotaxis of Jurkat and peripheral blood T lymphocytes.39 p38 MAPK is important for neutrophil emigration and chemotaxis, but it does not regulate integrin-mediated adhesion during these processes.40 In the current study, inhibition of p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK, or PI3K did not prevent α4 integrin affinity up-regulation by fMLP or SDF-1. Inhibition of p44/42 MAPK did not affect leukocyte arrest or adhesion, although a role in chemotaxis has been described. Chemokine triggering of high-affinity αLβ2 integrins on lymphocytes and αMβ2 integrins on neutrophils is also independent of PI3K activity.17,41,42 LDV-FITC binding returned to baseline more rapidly following wortmannin treatment, suggesting that PI3K may function to prolong or stabilize the high-affinity conformation of α4β1 integrin. However, LY294002, a structurally distinct PI3K inhibitor, did not inhibit LDV-FITC binding at concentrations that inhibited fMLP- and SDF-1–induced phosphorylation of AKT. The depression of LDV-FITC binding in the presence of wortmannin may therefore be attributed to previously described off-target effects on other kinases such as myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and PI4-kinase or phospholipase D.43 A previous report demonstrated that PI3Kα was necessary for MCP-1–mediated arrest and firm adhesion of rolling monocytes on ICAM-1 and VCAM-1.22 We confirmed a role for PI3K in the arrest and firm adhesion of U937 cells and human monocytes using LY294002 (S.J.H. and M.D.P., unpublished data, May 2004). These data suggest that PI3K mediates monocyte adhesion by a mechanism that is independent or downstream of α4 integrin affinity modulation. In contrast to monocytes, SDF-1–stimulated α4 integrin-mediated tethering and arrest of peripheral blood T cells was independent of PI3K.19

Other signaling pathways have been implicated in the regulation of α4 integrin affinity. The src kinase p56lck participates in the maintenance of high-affinity α4β1 integrin in T lymphocytes and SDF-1–induced arrest.44 However, in preliminary studies using a src kinase family inhibitor (PP2), no effect on LDV-FITC binding was observed, suggesting that src kinases are not involved in chemoattractant- or chemokine-mediated up-regulation of monocyte α4 integrin affinity (J.R.C., unpublished data, November 2002).

SDF-1– and fMLP-induced up-regulation of binding of VCAM-1 and LDV peptide and monocyte arrest was dependent on activation of PLC. Chemoattractants and chemokines act through PLC to hydrolyze PIP2 to IP3 and diacylglycerol, which mobilize intracellular calcium and activate protein kinase C, respectively.45 Blockade of IP3 receptors, but not of PKC, eliminated fMLP- and SDF-1–stimulated ligand binding and arrest. PKC has been implicated in both affinity and valency regulation of numerous integrins. In fact, phorbol esters have been used for many years as a method to induce integrin activation. In agreement with other recent studies,32 we have demonstrated a phorbol ester–inducible up-regulation of α4β1 integin affinity for peptide (Figure 2) and VCAM-1 (S.J.H., unpublished data, August 2005), but the PKC-induced up-regulation of α4β1 integrin affinity has kinetics distinct from those induced by GPCR, and chemokine-induced affinity changes were not dependent on PKC signaling. Similarly, affinity regulation of β2 integrins by chemokines is independent of PKC activity,18 although LFA-1 affinity for ICAM-1 is also regulated by PMA. Arrest of SDF-1–stimulated peripheral blood leukocytes on ICAM-1 is unaffected by inhibitors of PKC.37 Recent data suggest that PMA induces an intermediate-affinity conformation of LFA-1 that is extended but has a closed headpiece.15

A role for elevated [Ca2+]i was established by chelating intracellular calcium with BAPTA. In addition, treatment with ionomycin or thapsigargin, which increase [Ca2+]i in the absence of GPCR-signaling, was sufficient to induce LDV-FITC and VCAM-1 binding, although the magnitude of these responses was lower than for fMLP. Shear stress also increases α4β1 integrin affinity for LDV peptide in a calcium-dependent manner.46 In addition, Rap1-induced α4β1 integrin-mediated adhesion is dependent on calcium signaling but not p44/42 MAPK.47 A rapid increase in [Ca2+]i within seconds of chemoattractant stimulation is consistent with the rapid activation of integrins necessary for triggering of arrest. Intracellular calcium is a ubiquitous and pleiotropic signaling molecule capable of binding to many proteins. Our data suggest that entry of extracellular calcium is a key element regulating chemoattractant and chemokine stimulation of α4 integrin affinity. The coupling of chemoattractant receptors with a plasma membrane calcium channel may provide a mechanism by which chemoattractants stimulate only those integrins in close apposition to the chemoattractant receptor to restrict and localize integrin activation. The mechanisms linking increased [Ca2+]i to integrin activation have yet to be elucidated; however, our data suggest that calmodulin is a major effector of the calcium mediated α4β1 affinity up-regulation. Calcium binding to calmodulin results in marked changes in its conformation that enable it to bind and influence the function of a large number of proteins, including calcineurin, MLCK, and calmodulin kinase II.33 Additionally, Rap1-mediated integrin adhesion is dependent on calmodulin.47 Whether these or other pathways regulate α4β1 integrin affinity is a topic for future study.

The LDV-FITC peptide ligand can be used to detect different affinity states of α4β1 integrin in real time.23,48 Affinity of α4β1 for LDV peptide is regulated by changes in the dissociation constant, with decreased off rates primarily contributing to higher affinity.23 Similarly, affinity of α4β1 for VCAM-1 is also regulated by the off rate.48 Although there is a strong correlation between the dissociation constants for LDV-FITC and for FITC-conjugated VCAM-1 the dissociation constants for LDV-FITC were 2 orders of magnitude lower than those for VCAM-1.48 In our assays, the kinetics and relative magnitude of VCAM-1 and LDV-FITC binding induced by fMLP and Ca2+-mobilizing agents thapsigargin and ionomycin were comparable. In addition, Mn2+ and phorbol ester stimulation induce parallel increases in binding of LDV peptide and VCAM-1 by α4β1 integrins. Thus, changes in α4β1 integrin affinity induced by chemoattractant stimulation of GPCRs are reflected by binding of FITC-conjugated LDV peptide and soluble VCAM-1. Additionally, our studies with pharmacologic inhibitors revealed concordant signaling pathways regulating binding of peptide and native ligands. Binding of LDV peptide, monomeric and dimeric VCAM-1 was dependent on signaling via PLC, IP3 receptors, extracellular calcium entry, and calmodulin. Incomplete inhibition of up-regulated LDV binding by calcium chelation with BAPTA may be because some cytoplasmic calcium-binding proteins have a higher affinity for calcium than BAPTA.

We and others have demonstrated that arrest of rolling leukocytes is dependent on high-affinity integrins.16-18 The current data support this. Activation of PLC, influx of extracellular calcium, and activation of calmodulin regulate chemokine-induced α4β1 integrin affinity regulation and arrest on VCAM-1. Arrest on endothelial monolayers, which express adhesion molecules other than VCAM-1, is also dependent on PLC and intracellular calcium underscoring the importance of integrin affinity in leukocyte arrest.

Modulation of integrin binding to ligand can occur without changes in affinity or conformation. Integrin valency is regulated by the density of ligand, the geometric arrangement of integrins, and the ability of integrins to move into the region of adhesion.11 Several studies have suggested that chemokines rapidly modulate integrin valency.19,49 However, recent studies suggest that LFA-1 microclustering is dependent on affinity up-regulation and ligand binding.15 Thus, understanding the signaling pathways that regulate integrin affinity has implications not only for arrest but also for modulation of other integrin-dependent processes such as adhesion and migration.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: S.J.H. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; J.R.C. and S.T.D. designed and performed the research and analyzed data; M.C., M.D.P., G.C.D., and K.S. performed the research; T.K.W. contributed reagents; A.K. designed the research and contributed reagents; and M.I.C. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

S.J.H. and J.R.C. contributed equally to this study.

We thank Dr David Isenman (University of Toronto) for providing 125-I–labeled human IgG and assisting with the determination of VCAM-1 density.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP-14151). M.I.C. is a recipient of a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. J.R.C. is a recipient of a Doctoral Research Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. S.T.D. is a recipient of the Post-graduate Traveling Fellowship in Surgery, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal