Abstract

Dasatinib (BMS-354825), a novel dual SRC/BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor, exhibits greater potency than imatinib mesylate (IM) and inhibits the majority of kinase mutations in IM-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). We have previously demonstrated that IM reversibly blocks proliferation but does not induce apoptosis of primitive CML cells. Here, we have attempted to overcome this resistance with dasatinib. Primitive IM-resistant CML cells showed only single-copy BCR-ABL but expressed significantly higher BCR-ABL transcript levels and BCR-ABL protein compared with more mature CML cells (P = .031). In addition, CrKL phosphorylation was higher in the primitive CD34+CD38– than in the total CD34+ population (P = .002). In total CD34+ CML cells, IM inhibited phosphorylation of CrKL at 16 but not 72 hours, consistent with enrichment of an IM-resistant primitive population. CD34+CD38– CML cells proved resistant to IM-induced inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation and apoptosis, whereas dasatinib led to significant inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation. Kinase domain mutations were not detectable in either IM or dasatinib-resistant primitive CML cells. These data confirm that dasatinib is more effective than IM within the CML stem cell compartment; however, the most primitive quiescent CML cells appear to be inherently resistant to both drugs.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal hemopoietic disorder that is sustained by a population of primitive and transplantable stem cells.1 These stem cells are Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) and express the oncogenic tyrosine kinase BCR-ABL.2,3 BCR-ABL is central to the pathogenesis of CML, and mutation of critical elements leads to a reduction in transformation potential.4,5 In the malignant clone, BCR-ABL is constitutively active, resulting in autophosphorylation of the kinase domain and of downstream substrates including CrKL.6,7 The specificity of CrKL phosphorylation to BCR-ABL signaling, partnered with stability of the phosphoprotein complex, has led to its acceptance as an excellent method to assess BCR-ABL status.8-10

Imatinib mesylate (IM) has been introduced as first-line targeted therapy for CML. IM is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is relatively specific for BCR-ABL.11 In vitro, in Ph+ cell lines and in bulk cultures of primary CML cells, IM reverses the autophosphorylation of BCR-ABL and inhibits phosphorylation of downstream targets including CrKL.11,12 Within 48 to 72 hours of IM exposure, CML cells undergo apoptosis. More recently, Chu et al13 have confirmed that CrKL phosphorylation is also inhibited by IM in CD34-enriched populations of primary CML cells. However, our own work and that of others confirms that primitive CML cells do not readily undergo apoptosis, even after prolonged in vitro exposure to the drug.14-17 The link between inactivation of BCR-ABL kinase activity and induction of apoptosis in the most primitive CML cells therefore remains unclear.

In vivo, even in chronic phase, clinical responses to IM are quite heterogeneous. IM induces complete cytogenetic response (CCR), which appears durable, in the majority of newly diagnosed patients.18 However, few patients achieve a complete molecular remission, with only 4% achieving consistent reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)–negative status by 30 months in the International Randomized Study of Interferon versus STI571 (IRIS) trial.19,20 Furthermore, some patients exhibit either primary or acquired resistance to IM.19,21 Current knowledge suggests that IM resistance is likely to be multifactorial, with the underlying mechanisms varying depending on stage of disease, duration of exposure to IM, and genetic instability within the malignant clone. For newly diagnosed cases treated with IM and achieving CCR, at least 2 mechanisms may account for minimal residual disease (MRD): genetic resistance induced by tyrosine kinase mutations,12,22,23 which have been shown to exist prior to IM therapy in a subpopulation of patients,24,25 and/or disease persistence, resulting from inherent insensitivity of CML stem cells to IM.14,16,26,27

There is mounting evidence that CML stem cells are not eliminated by IM in vivo, with patients in CCR having easily detectable Ph+ CD34+ cells, colony-forming cells (CFCs), and long-term culture initiating cells (LTC-ICs).16 Given the demonstrated insensitivity of these cells to IM in vitro, it is plausible that they would become the dominant persisting population of CML cells remaining after IM treatment. The rapid relapses observed in some patients who have discontinued IM after a period of PCR negativity would support this.28,29 Whether CML stem cells with wild-type BCR-ABL sequence coexist with clones expressing BCR-ABL kinase mutations in the same patient and both contribute to IM resistance is currently unknown.

The primitive quiescent CML cells that we have previously shown to be insensitive to IM in vitro represent less than one percent of total CD34+ cells present at diagnosis and may explain MRD in patients. In this study, we have investigated underlying mechanisms for IM resistance of primitive CML populations and attempted to overcome IM resistance with the novel drug dasatinib (BMS-354825).

Materials and methods

Reagents

IM was a kind gift from Dr Elisabeth Buchdunger, Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland). Stock solutions (100 mM) were prepared in sterile distilled water and stored at 4°C. Dasatinib was obtained from Dr Francis Lee (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ). A stock solution of 10 mg/mL in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) was prepared and stored in aliquots at –20°C.

Cell lines

The BCR-ABL–expressing K562 and non-BCR-ABL–expressing HL60 human leukemia cell lines were grown in suspension in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich Company, Dorset, United Kingdom) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom), 1% glutamine (100 mM; Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 mM; Invitrogen) (RPMI+) in a humidified incubator at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Every 3 to 4 days, cells were counted using a hemocytometer and set up at 1 × 106 cells per flask with fresh RPMI+.

Primary cell samples

Fresh leukapheresis products from patients (n = 10) with chronic phase CML, at or early postdiagnosis, prior to any exposure to IM in vivo, were enriched for CD34+ cells using a clinical scale method of magnetic-activated cell sorting, CLINIMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Bisley, United Kingdom). The selected cells were then cryopreserved in 10% (vol/vol) DMSO in ALBA (4% [wt/vol] human albumin solution; Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service, Glasgow, United Kingdom) and stored in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen until required. All human cell samples were obtained with informed consent. Ethics approval was obtained for these studies from the North Glasgow University Hospitals NHS Trust review board.

In vitro cell culture

Primary CML cells were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM, Sigma) supplemented with a serum substitute (bovine serum albumin [BSA], insulin, transferrin [BIT]; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and 0.1 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) (serum-free medium [SFM]). SFM was further supplemented with a 5 growth factor (5GF) cocktail comprising 100 ng/mL Flt3-ligand, 100 ng/mL stem cell factor, and 20 ng/mL each of interleukin (IL)–3, IL-6 (all from StemCell Technologies), and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF; Chugai Pharma Europe, London, United Kingdom).

FISH

Aliquots of more than 5000 cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/2% FCS and resuspended in a prewarmed (37°C) hypotonic solution (0.075 M potassium chloride). Aliquots of cells were spotted onto multispot microscope slides (Hendley, Essex, United Kingdom) previously coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature before excess hypotonic solution was gently removed. Cell fixation was performed by addition of 20 μL of freshly prepared methanol–acetic acid (3:1) to each well with incubation at room temperature until dry. This fixation step was repeated, with final fixation in a Coplin jar for 5 minutes before air drying of the slide overnight. Slides were wrapped in parafilm and stored at –20°C until fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed with the LS1 BCR-ABL Dual Colour, Dual Fusion translocation probe according to the manufacturers' instructions (Abbott Diagnostics, Maidenhead, United Kingdom). Interphase nuclei were evaluated using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems UK, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) with a triple-band pass filter for DAPI, Spectrum Orange, and Spectrum Green.

RT-PCR and BCR-ABL kinase mutation analyses

For quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR) analyses, RNA was extracted from a minimum of 1 × 105 sorted cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturers' instructions. cDNA was generated using Random Hexamers (Pharmacia, Tadworth, United Kingdom) and stored at –20°C until analyzed. The Q-PCR was performed as previously described30 but using standard curves created from a plasmid supplied by Jaspal Kaeda, Hammersmith Hospital, London. The Q-PCR was carried out on the ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using a plasmid standard curve and the following BCR-ABL primers and probe (Eurogentec, Belgium)30 : ENF 501 TCCGCTGACCATCAAYAAGGA, ENR 561 CACTCAGACCCTGAGGCTCAA, ENP 541 FAM-CCCTTCAGCGGCCAGTAGCATCTGA-TAMRA. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included in the analyses. The BCR-ABL copy number was normalized to the number of cells used in the analyses, allowing for the comparison between the sorted populations. Five patient samples were analyzed in this way and the data merged with the appropriate errors depicted. The Student t test was used to show statistical significance. Mutation detection within the Abl kinase domain was carried out using a protocol obtained from Susan Branford.31,32 RNA was extracted and cDNA generated as described. The abl kinase domain was PCR amplified using the following PCR primers: forward primer TGACCAACTCGTGTGTGAAACTC and reverse primer TCCACTTCGTCTGAGATACTGGATT and the expand long template PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The PCR product was cleaned using the Qiagen PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen). The sequencing reactions were set up using the above primers and the Beckman Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kit. The sequences were analyzed on the Beckman CEQ 8000 (Beckman Coulter, CA), according to the manufacturers' instructions. Sequence comparisons were carried out using the Blast programs available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), with the ABL sequence M14752.

Flow cytometry, CrKL phosphorylation assay, and enrichment for CD34+CD38– cells

CD34+ cells were recovered from liquid nitrogen, washed once in PBS/2% FCS, an aliquot reserved for FISH, BCR-ABL RT-PCR, and mutation analysis, an aliquot labeled with anti–CD34-PE (BD Pharmingen, Oxford, United Kingdom) and 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma), and an aliquot labeled for phosphorylated CrKL (P-CrKL). HL-60 cells and CD34+ samples from non-CML leukapheresis procedures were used as BCR-ABL–negative controls for K562 cells and primary CD34+ CML cells, respectively. To assess CrKL phosphorylation, at least 1 × 105 CML cells were resuspended in 100 μL fixing reagent from a Fix and Perm kit (Caltag Laboratories, Silverstone, United Kingdom) and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The cells were then washed with 3 mL PBS/0.1% BSA/0.1% azide buffer (PBS/BSA/azide) and centrifuged at 120g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was poured off and 25 μL permeabilizing reagent added. 2.5 μL of P-CrKL antibody (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom) was added directly to this buffer, the cells vortexed, and then incubated at room temperature for 40 minutes. The wash step was then repeated twice and the cells resuspended in 100 μL PBS/BSA/azide. Secondary antibody (anti–rabbit IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]-conjugate) (Sigma) was added directly to this buffer, the cells vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark. The wash step was repeated twice, and the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. The remaining CD34+ cells were split, with more than 50% reserved for enrichment of CD34+CD38– cells, which was performed according to the manufacturers' instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). CD38+ and CD38– cells were separated using biotinylated anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody and anti-biotin MACSibeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD34+CD38– profile of these cells was confirmed by flow cytometry. Total CD34+ and enriched CD34+CD38– cells were then cultured as indicated for 16 and 72 hours in SFM. The resulting FACS data were normalized so that the no-drug control for each patient sample had P-CrKL of 100%, and then the result with each treatment arm was calculated based on a percentage of this. At 16 and 72 hours the cells were harvested and viability assessed by counting in a hemocytometer in a 20% solution of Trypan blue.

Western blotting

We washed 1 × 105 primary CML cells twice in ice-cold PBS and then lysed them in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitor mixture, and phosphatase inhibitors (0.1 M Na3VO4 and 0.1 M NaF [all from Sigma]). Protein lysates from 1 × 105 cells were separated on 4% to 15% Tris-HCl gradient gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Bucks, United Kingdom), and blocked in 5% BSA/PBS-Tween (0.01%) (PBS-T). Membranes were then rinsed in PBS-T and incubated overnight at 4°C with either antibodies against the activated form of CrKL, anti–P-CrKL (1:1000; New England Biolabs) in 5% BSA/PBS-T, c-ABL (1:1000; BD), or phospho-tyrosine primary antibody (P-Tyr; 4G10 clone; 1:1000; Upstate) in 5% milk/PBS-T. Membranes were then washed 5 times in PBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–linked secondary antibodies (1:3000; New England Biolabs) for 1 hour at room temperature. Antibody detection was performed using ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were then stripped in 1 × Re-Blot Plus Strong Antibody Stripping Solution (Chemicon, Hampshire, United Kingdom) for 15 minutes at room temperature and reprobed with anti–pan-actin antibody (1:1000; New England Biolabs) in 5% BSA/PBS-T to confirm equal protein loading, as expression of pan-actin remains constant in response to the different treatment conditions we used. Developed films were scanned with an Epson scanner, and the integrated density of protein bands was determined with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

CFSE tracking of cell division

Following recovery from liquid nitrogen, CD34+ CML cells were stained with 1 μM carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl diester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as described in detail previously.33-35 These cells were then cultured for 6 days in SFM plus 5GF under test conditions. After 3 and 6 days, the cells were harvested, total cell viability assessed, and an aliquot of cells from each condition stained with anti–CD34-PE and PI for flow cytometry analysis. Cells cultured in the presence of 100 ng/mL colcemid (Invitrogen), which arrests cell cycle progression, were used to establish the CFSEmax undivided cell population at both time points.

To measure the overall effect of each test condition on cell survival and number of undivided cells remaining after 3 and 6 days in culture, the percentage recovery of viable (PI–) CD34+ cells in the undivided CFSEmax peak was calculated as previously described14 and expressed as a proportion of the starting CD34+ cell number. This permitted an assessment of test condition efficacy against primitive CML cells. Results were calculated separately for each test condition in all experiments and then averages were calculated (± SEM) for all conditions.

Measurement of intracellular IM levels

To investigate whether there were differences in the drug penetrance of these cells we incubated the CD34+ and CD34+CD38– from 3 CML samples with a range of extracellular concentrations of 14C-IM (0-10 μM; kindly provided by Dr Elisabeth Buchbunger, Novartis). Aliquots of 1 × 105 cells were incubated with the drug for 1 hour, after which the cells were briefly washed and pelleted before measurement of the radioactive drug in the cellular pellets by scintillation counting as previously described.36

Results

The majority of CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells, before and after short-term IM exposure, are BCR-ABL positive and do not show gene amplification

Previous investigators have reported amplification of the BCR-ABL gene in Ph+ cell lines derived from blast crisis CML patients and in primary cells from patients with advanced phase disease.12,37,38 Furthermore, the degree of gene amplification has been shown to increase with prolonged exposure to IM, either in vitro or in vivo.39 However, gene amplification previously has not been reported in early chronic phase. Another critical issue when dealing with more primitive CML cell populations is the coexistence of Ph–/BCR-ABL– cells. Since our previous work had shown that primitive CML cells were insensitive, in terms of apoptosis, to even 10 μM IM,14 it was important to demonstrate whether these highly purified populations showed evidence of gene amplification. As shown in Table 1, for all early chronic phase patients for whom these analyses were possible, only a single copy of the BCR-ABL gene was ever detected. Furthermore the majority of primitive cells, both before and following IM or dasatinib exposure, were BCR-ABL positive. We are therefore confident that neither gene amplification nor enrichment of normal cells is an explanation for their drug resistance.

D-FISH results for CD34+ and CD34+38- cells enriched from CML samples before and after 72 hours of exposure to IM and/or dasatinib

. | . | CD34+ after IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | . | . | CD34+CD38- after IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. . | CD34+ pre-IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | IM . | Dasatinib . | CD34+CD38- before IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | IM . | Dasatinib . | ||

| 1 | 65/78 (83) | 46/72 (64) | 52/78 (67) | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 2 | 443/443 (100) | 73/78 (94) | 86/87 (99) | 132/132 (100) | ND | 87/89 (98) | ||

| 3 | 333/336 (99) | 35/35 (100) | 332/334 (99) | 355/357 (99) | ND | 207/210 (99) | ||

| 4 | 277/314 (88) | ND | ND | 37/39 (95) | 27/28 (96) | 31/32 (97) | ||

| 5 | 221/253 (87) | ND | ND | 357/393 (85) | 91/107 (85) | 28/30 (93) | ||

| 6 | 115/118 (97.5) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 7 | 166/166 (100) | ND | 253/253 (100) | 115/115 (100) | 230/230 (100) | 167/169 (99) | ||

| 8 | 160/176 (90.9) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 9 | 47/47 (100) | ND | ND | 56/58 (97) | 125/126 (99) | ND | ||

| 10 | 501/555 (90.3) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

. | . | CD34+ after IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | . | . | CD34+CD38- after IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. . | CD34+ pre-IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | IM . | Dasatinib . | CD34+CD38- before IM/Das BCR-ABL+ cells/total cells (%) . | IM . | Dasatinib . | ||

| 1 | 65/78 (83) | 46/72 (64) | 52/78 (67) | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 2 | 443/443 (100) | 73/78 (94) | 86/87 (99) | 132/132 (100) | ND | 87/89 (98) | ||

| 3 | 333/336 (99) | 35/35 (100) | 332/334 (99) | 355/357 (99) | ND | 207/210 (99) | ||

| 4 | 277/314 (88) | ND | ND | 37/39 (95) | 27/28 (96) | 31/32 (97) | ||

| 5 | 221/253 (87) | ND | ND | 357/393 (85) | 91/107 (85) | 28/30 (93) | ||

| 6 | 115/118 (97.5) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 7 | 166/166 (100) | ND | 253/253 (100) | 115/115 (100) | 230/230 (100) | 167/169 (99) | ||

| 8 | 160/176 (90.9) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 9 | 47/47 (100) | ND | ND | 56/58 (97) | 125/126 (99) | ND | ||

| 10 | 501/555 (90.3) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

Das indicates dasatinib; ND, not done.

Primitive CML cells express higher levels of BCR-ABL transcripts than their more mature counterparts

There has been controversy regarding whether all Ph+ cells express BCR-ABL transcripts. In 1994, Keating et al40 reported that single colonies analyzed by cytogenetics and RT-PCR could be Ph+ but RT-PCR negative. In addition, Bedi et al41 found that in primitive CML progenitors, there was minimal or absent BCR-ABL expression by RT-PCR, but significant production of the P210 protein by immunoperoxidase assay. Similarly, it has been shown that patients treated with allogeneic transplantation had BCR-ABL–positive cells detected by FISH that were apparently transcriptionally silent.42,43 These data were challenged by Deininger et al44 and by Chase et al,45 with neither study able to detect BCR-ABL–positive cells in patients in stable remission following allografting. Since some of the primitive CML cells we isolated remained quiescent in culture, it was important to determine whether they were transcriptionally silent. Using standard single-round RT-PCR, BCR-ABL was detectable in all enriched populations of CD34+ and CD34+CD38– cells and in the same cells following 72 hours of exposure to IM (data not shown), confirming that these cells were both RT-PCR and FISH positive for BCR-ABL (Table 1). Very recently, Jiang et al46 suggested that BCR-ABL transcript levels may be up to 200-fold greater in the most primitive CML progenitors as compared to their more differentiated counterparts. If confirmed, this might explain the marked insensitivity of such cells to IM. We therefore performed real-time quantitative RT-PCR on RNA extracted from identical starting numbers of MNCs and CD34+ and CD34+CD38– cells from 5 newly diagnosed cases of CML in chronic phase (Figure 1A). As shown, transcript levels were significantly higher for total CD34+ (P = .016) and CD34+CD38– cells (P = .031) than for MNCs.

Comparison of BCR-ABL transcripts and BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL protein expression levels between MNC, CD34+, and CD34+CD38– CML cells. (A) The expression level of BCR-ABL was determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to cell number used in the assay. Five patient samples were tested in this way and the results combined. The figure shows the expression level of BCR-ABL in the sorted cell populations as a product of the MNC population level (P = .016 for MNC versus CD34+ cells and P = .031 for MNC versus CD34+CD38– cells). These results show that the expression levels differ by at least 10-fold between the MNC population and the 2 stem cell populations. There was no significant difference between the CD34+ and the CD 34+CD38– populations. BCR-ABL (B), P-Tyr (C), and P-CrKL (D) protein expression levels in total MNCs and CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells from 3 newly diagnosed chronic phase CML patients were assessed by Western blotting. Protein expression was quantified using relative densitometry (bar charts above blots). These experiments showed that BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL were highest in the most primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation and lowest in the mature total MNC fraction. RD indicates relative density.

Comparison of BCR-ABL transcripts and BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL protein expression levels between MNC, CD34+, and CD34+CD38– CML cells. (A) The expression level of BCR-ABL was determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to cell number used in the assay. Five patient samples were tested in this way and the results combined. The figure shows the expression level of BCR-ABL in the sorted cell populations as a product of the MNC population level (P = .016 for MNC versus CD34+ cells and P = .031 for MNC versus CD34+CD38– cells). These results show that the expression levels differ by at least 10-fold between the MNC population and the 2 stem cell populations. There was no significant difference between the CD34+ and the CD 34+CD38– populations. BCR-ABL (B), P-Tyr (C), and P-CrKL (D) protein expression levels in total MNCs and CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells from 3 newly diagnosed chronic phase CML patients were assessed by Western blotting. Protein expression was quantified using relative densitometry (bar charts above blots). These experiments showed that BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL were highest in the most primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation and lowest in the mature total MNC fraction. RD indicates relative density.

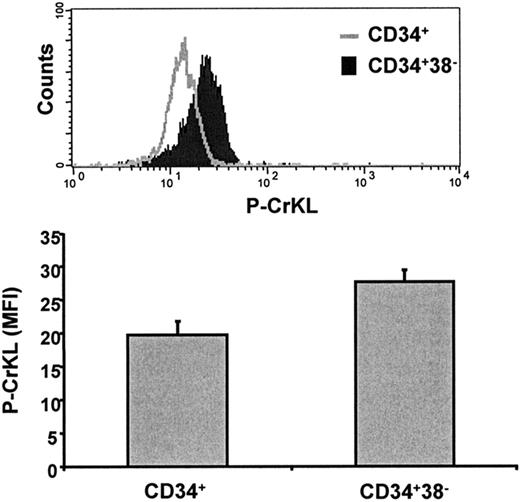

Primitive CML cells have high BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL protein expression

Having shown that BCR-ABL transcripts were high, we went on to assess BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL protein expression in total MNCs, total CD34+ CML cells, and CD34+CD38– CML cells by Western blotting. BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL were highest in the most primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation (Figure 1B-D). In addition, P-CrKL was assessed using a novel intracellular FACS method (described in “Flow cytometry, CrKL phosphorylation assay, and enrichment for CD34+CD38– cells”). This confirmed significantly increased P-CrKL in the primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation (P = .002; Figure 2). This suggests that BCR-ABL is a relevant target in primitive CML stem cells.

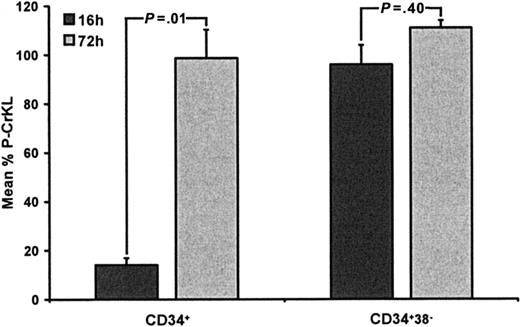

IM-resistant CD34+ cells and IM-naive CD34+CD38– CML cells do not undergo inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation in response to IM

To assess BCR-ABL kinase status in response to IM exposure, in small numbers of CD34+ and CD34+CD38– cells from CML patients, we developed an intracellular flow cytometry assay to measure percentage P-CrKL. In most instances, starting cell numbers were between 1 and 10 × 105, with fewer cells remaining after drug treatment, making Western blotting impossible. The assay was established with HL60 and K562 cell lines, using a 16-hour time point to examine immediate effects on P-CrKL and a 72-hour time point to examine P-CrKL status in those cells that survived drug treatment. IM was used at 5 μM (∼IC90) and added at baseline and again at 60 hours. HL60 cells (BCR-ABL negative) showed no P-CrKL, whereas K562 initially showed high-level P-CrKL that was inhibited by approximately 80% at 16- and 72-hour time points (data not shown). For CD34+ cells, IM induced a mean 86% reduction in P-CrKL at 16 hours, suggesting that the majority of CD34+ cells were IM sensitive (Figure 3). However, despite re-exposure to IM 12 hours before the 72-hour time point, those cells that survived IM showed no reduction in P-CrKL (mean, 1.3%; P = .01 for 16-hour versus 72-hour data), consistent with enrichment, following cell death, of an IM-resistant population. For the more primitive CD34+CD38– cells (< 5% of total CD34+), IM did not reduce P-CrKL at either time point (mean reductions, 4% versus +11% at 16 and 72 hours, P = .40; Figure 3), suggesting that these cells were inherently resistant to IM. At 5 μM, IM induced a 69% reduction in CD34+ cells by 72 hours as compared to only 47% for CD34+CD38– cells (P = .03), in keeping with P-CrKL data. This reduction in total cell numbers is mainly due to the antiproliferative effects of IM, with a modest contribution from increased cell kill. To overcome potentially increased transcripts/tyrosine kinase activity in more primitive cells and in an attempt to increase intracellular drug levels, these experiments were repeated using 10, 25, and 50 μM IM. At these higher concentrations, the drug induced increased cell death in both CML and healthy donor samples with no evidence of enhanced inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation in surviving Ph+ cells (data not shown). In addition, preliminary experiments showed considerable dose-dependent accumulation of 14C-IM after a 1-hour incubation in both CD34+CD38– cells and the less-primitive CD34+ CML cells. However, the concentrations within the 2 groups of cells were very similar, and there was no significant difference at any dose. Incubation with 10 μM 14C-IM resulted in mean values of 575 ng/1 × 105 cells in CD34+ cells and 597 ng/1 × 105 cells in the CD34+CD38– fraction (n = 3 in triplicate). Furthermore, after 72 hours of treatment with IM, cellular concentration in remaining viable cells (P-CrKL+) was maintained or even increased. This suggests that drug influx/efflux is not a major contributory factor to the IM insensitivity seen in these cells.

Assessment of P-CrKL in CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells using a novel intracellular flow cytometry method. P-CrKL status was measured by this intracellular FACS technique using a P-CrKL primary antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. These experiments confirmed significantly increased P-CrKL in the primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation compared with total CD34+ cells (P = .002). MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity.

Assessment of P-CrKL in CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells using a novel intracellular flow cytometry method. P-CrKL status was measured by this intracellular FACS technique using a P-CrKL primary antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. These experiments confirmed significantly increased P-CrKL in the primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation compared with total CD34+ cells (P = .002). MFI indicates mean fluorescence intensity.

P-CrKL in CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM. CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells (n = 8) were cultured with or without IM (5 μM) for 72 hours. Intracellular FACS was used to measure P-CrKL status at 16 and 72 hours. After 16 hours, CD34+ cells treated with IM (5 μM) showed an 86% decrease in P-CrKL, as compared to no-drug control (100%). After re-exposure to IM at 60 hours, the surviving CD34+ cells showed minimal reduction in P-CrKL at 72 hours (–1.3%) (P = .01). CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM (5 μM) showed little dephosphorylation or even hyperphosphorylation of CrKL at either 16-(–4%) or 72-hour (+11%) time points, respectively (P = .40), as compared to no-drug control (100%).

P-CrKL in CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM. CD34+ and CD34+CD38– CML cells (n = 8) were cultured with or without IM (5 μM) for 72 hours. Intracellular FACS was used to measure P-CrKL status at 16 and 72 hours. After 16 hours, CD34+ cells treated with IM (5 μM) showed an 86% decrease in P-CrKL, as compared to no-drug control (100%). After re-exposure to IM at 60 hours, the surviving CD34+ cells showed minimal reduction in P-CrKL at 72 hours (–1.3%) (P = .01). CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM (5 μM) showed little dephosphorylation or even hyperphosphorylation of CrKL at either 16-(–4%) or 72-hour (+11%) time points, respectively (P = .40), as compared to no-drug control (100%).

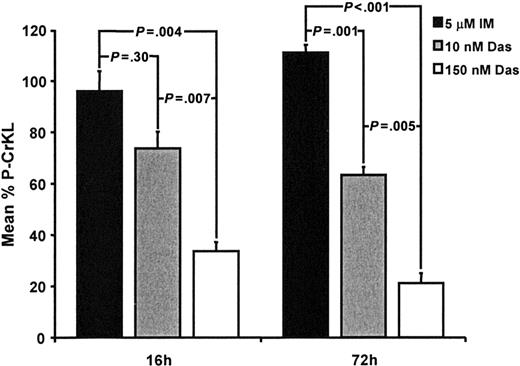

Dasatinib inhibits CrKL phosphorylation and reduces total cell numbers in CD34+CD38– cells at a clinically achievable concentration

Dasatinib, a dual SRC/BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor, has now entered phase 2 clinical trials for patients with Ph+ leukemias. In vitro, dasatinib has been shown to be more potent than IM against BCR-ABL and to inhibit the majority of kinase domain mutants associated with IM resistance.47 Furthermore, conformation of the BCR-ABL kinase domain does not appear to be critical for drug binding as compared to IM.47,48 Dasatinib was therefore compared directly with IM using the P-CrKL assay and cell kill of the CD34+CD38– population. Dasatinib was tested at 10 nM (∼IC50) and 150 nM (below the maximal concentration achievable in phase 1 trials of 180 nM). As shown in Figure 4, even at 10 nM, dasatinib showed a trend toward enhanced inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation as compared to IM at 16 hours. This achieved statistical significance at the 72-hour time point (P = .001). Whereas increasing the concentration of IM to 10 to 50 μM caused nonspecific cell death without inhibiting CrKL phosphorylation, dasatinib at 150 nM retained selectivity for Ph+ cells (data not shown) and induced further significant reductions in P-CrKL by 66% and 79% of control at 16 and 72 hours, respectively (P = .007 and .005 versus dasatinib 10 nM and P = .004 and P < .001 versus IM 5 μM). The reduction in P-CrKL correlated with a reduction in total cell numbers. Dasatinib 10 nM induced a 33% reduction in total cells at 72 hours, increasing to 60% with 150 nM (P = .015 for 10 nM versus 150 nM dasatinib).

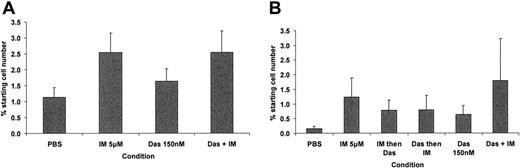

Dasatinib induces a less profound antiproliferative effect than IM against primitive CML cells but does not target the quiescent fraction

Although CD34+CD38– cells represent the more primitive end of the CD34+ compartment (< 5% of total CD34+ cells), our previous work has identified those CD34+ cells that remain quiescent in culture to be most resistant to IM (< 1% of total CD34+ cells).14 CFSE was therefore used to enable high-resolution tracking of cell division, within the CD34+ population, upon exposure to IM and/or dasatinib. Cells that retain maximal CFSE fluorescence (CFSEmax) represent quiescent CD34+ cells that have not yet undergone a first cell division by 3 or 6 days, in the presence of a potent 5GF cocktail. With the addition of antiproliferative agents, the CFSEmax gate comprises 2 cell populations: those that were destined to remain quiescent in culture and that do not undergo apoptosis in response to drug exposure (quiescent stem cells), and those that were destined to enter division in the presence of 5GFs, yet upon drug exposure enter a reversible G1 arrest, resulting in their accumulation within the CFSEmax gate (less immature). To date we have not been able to develop a method that will accurately differentiate these 2 cell fractions (except that G1 arrest does not occur in the no-drug-control arm), nor have we (or others) found a single agent or drug combination that will eliminate the CFSEmax population, or even reduce it significantly below that of the no-drug control.17,49 To compare the antiproliferative properties of IM with those of dasatinib and to assess the net effect of these drugs alone and in combination on total and CFSEmax cells, 6 test conditions were assayed: (1) no drug control, (2) IM alone for 6 days (5 μM), (3) dasatinib alone for 6 days (150 nM), (4) IM for 3 days then dasatinib for 3 days, (5) dasatinib for 3 days then IM for 3 days, and (6) IM plus dasatinib for 6 days. Endpoint analyses included total viable cell counts on days 3 and 6 and a calculation to determine the absolute number of viable CFSEmax cells remaining after 3 and 6 days for each condition. Dasatinib proved slightly less antiproliferative as compared to IM in terms of accumulation of cells in the earlier cell divisions. There was a significant increase in CFSEmax undivided cells (Figure 5A,B) in the IM and IM plus dasatinib arms at 3 days (P = .04 and P = .05, respectively) but not the dasatinib arm (P = .27) in comparison to the no-drug control. At 6 days, the IM-containing arms, taken as a group, had accumulated significantly more undivided cells in comparison to non-IM–containing arms (P = .045). This likely reflected the less-profound antiproliferative effect of dasatinib, causing less accumulation of cells in reversible G1 arrest within the CFSEmax gate. Disappointingly, none of the test arms reduced the CFSEmax population as compared to the no-drug control, suggesting that the most primitive quiescent cell population was not targeted.

P-CrKL in CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with 5 μM IM, 10 nM, and 150 nM dasatinib. As described in Figure 3, CD34+CD38– CML cells were cultured with or without IM (5 μM), 10 or 150 nM dasatinib. CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM showed no significant inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation at either 16 or 72 hours. Dasatinib (10 nM)–treated CD34+CD38– CML cells showed a 26% reduction in P-CrKL at 16 hours, as compared to no-drug control (100%), which was not significantly different to IM-treated cells (P = .30). After 72 hours, the difference between IM and dasatinib 10 nM was significant (P = .001). CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with 150 nM dasatinib showed increasing inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation at 16 and 72 hours (–66% and –79% of control, respectively) (P = .007 and .005 versus dasatinib 10 nM and P = .004 and P < .001 versus IM 5 μM). Das indicates dasatinib.

P-CrKL in CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with 5 μM IM, 10 nM, and 150 nM dasatinib. As described in Figure 3, CD34+CD38– CML cells were cultured with or without IM (5 μM), 10 or 150 nM dasatinib. CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with IM showed no significant inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation at either 16 or 72 hours. Dasatinib (10 nM)–treated CD34+CD38– CML cells showed a 26% reduction in P-CrKL at 16 hours, as compared to no-drug control (100%), which was not significantly different to IM-treated cells (P = .30). After 72 hours, the difference between IM and dasatinib 10 nM was significant (P = .001). CD34+CD38– CML cells treated with 150 nM dasatinib showed increasing inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation at 16 and 72 hours (–66% and –79% of control, respectively) (P = .007 and .005 versus dasatinib 10 nM and P = .004 and P < .001 versus IM 5 μM). Das indicates dasatinib.

IM- and dasatinib-resistant CD34+CD38– cells do not express mutant BCR-ABL

Following isolation of CD34+CD38– cells and their further enrichment for drug-resistant cells during 72 hours of drug exposure, mutant BCR-ABL would be expected to predominate if this represented the underlying mechanism for their drug resistance. RNA was purified from viable CD34+CD38– cells that survived exposure to either IM 5 μM or dasatinib 150 nM. Following PCR, the kinase domain was directly sequenced. In none of the samples with sufficient quality RNA (n = 5) was a mutant sequence detected.

The effect of IM 5 μM and dasatinib 150 nM on recovery of undivided cells using CFSE high-resolution tracking of cell division. Primary CFSE+ CD34+ CML cells were cultured as described with assessment of recovery of undivided CFSEmax CD34+ cells by flow cytometry at 3 and 6 days. (A) Undivided CFSEmax cells (± SEM) remaining after 3 and (B) 6 days of culture. At 3 days, there was a significant accumulation of undivided CFSEmax cells in the IM and IM plus dasatinib arms in comparison to the no-drug control (P = .04 and P = .05, respectively), and after 6 days of culture, there was a significant accumulation of these cells in the IM-containing test arms in comparison to the non-IM–containing arms (P = .045). Das indicates dasatinib.

The effect of IM 5 μM and dasatinib 150 nM on recovery of undivided cells using CFSE high-resolution tracking of cell division. Primary CFSE+ CD34+ CML cells were cultured as described with assessment of recovery of undivided CFSEmax CD34+ cells by flow cytometry at 3 and 6 days. (A) Undivided CFSEmax cells (± SEM) remaining after 3 and (B) 6 days of culture. At 3 days, there was a significant accumulation of undivided CFSEmax cells in the IM and IM plus dasatinib arms in comparison to the no-drug control (P = .04 and P = .05, respectively), and after 6 days of culture, there was a significant accumulation of these cells in the IM-containing test arms in comparison to the non-IM–containing arms (P = .045). Das indicates dasatinib.

Discussion

Resistance to IM can be described as BCR-ABL dependent or independent.12,50-53 For BCR-ABL–dependent resistance, upon exposure to IM the BCR-ABL kinase remains active, with downstream substrates such as CrKL fully phosphorylated.12 The principal mechanism underlying IM resistance in patients is mutation of BCR-ABL,12 leading to a change in conformation and failure of IM binding within the ATP pocket.51 This form of resistance has been shown to be BCR-ABL dependent.

Although it is clear that CML stem cells are relatively resistant to IM,14-17,49 leading to disease persistence even in optimally responding patients,16 the underlying mechanism(s) has not been determined, nor whether the resistance is BCR-ABL dependent or independent elucidated.27 We developed a flow cytometry assay to assess BCR-ABL kinase status indirectly by measuring the percentage of P-CrKL in the presence versus absence of IM or dasatinib. Following validation in K562 and HL60 cells, we were able to confirm that after IM exposure for 72 hours, CrKL remained fully phosphorylated in surviving CD34+ cells, in keeping with BCR-ABL–dependent resistance. This was confirmed by Western blotting. However, other BCR-ABL–independent mechanisms of IM resistance also may be operating in CML stem cells. Possible explanations to explain the BCR-ABL–dependent resistance seen here would include drug levels within the stem cell population that were insufficient to inhibit BCR-ABL kinase activity, either related to the balance between drug influx and efflux36,54,55 or to gene amplification,12 high transcript, or kinase activity levels13,46,56 within this specific cell type. Alternatively, the switch between active and inactive BCR-ABL conformations may differ within the stem cell compartment, resulting in less avid IM binding,48 or cells expressing kinase domain mutations that inhibit or prevent binding may be enriched within this population.51 We therefore attempted to address many of these points in an effort to better understand stem cell persistence.

D-FISH was used to confirm that the IM- or dasatinib-resistant primitive cells were indeed Ph/BCR-ABL+ and to exclude gene amplification as an explanation for their resistance. In these experiments, only low levels of Ph– cells were detected, and no evidence for gene amplification was found. We also are confident that primitive CML cells, including those that remain quiescent in culture, express BCR-ABL transcripts. In keeping with recent data from Jiang et al,46,56 we agree that transcript levels are significantly increased within the most primitive CML cells and that this may contribute to their IM resistance. In addition, we found increased protein expression of BCR-ABL, P-Tyr, and P-CrKL in the most primitive CD34+CD38– subpopulation, confirming the increased BCR-ABL activity in this fraction.

In an effort to overcome this increased BCR-ABL activity in the stem cell pool, we increased IM concentration to 10, 25, and even 50 μM. At these increased concentrations, IM was more toxic but lost selectivity between Ph–/BCR-ABL– CD34+ cells from healthy donor and CML samples. Since IM has a number of targets, such as c-kit, that are active in normal stem cell populations, this result was not surprising and consistent with the literature.11,57

The novel SRC/BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor, dasatinib, is now in clinical trials worldwide.58 Initial results are encouraging and, in vitro, the drug is more potent that IM,47 binds both active and inactive BCR-ABL conformations, and inhibits many of the kinase mutations that lead to IM resistance. This enhanced efficacy is likely mediated via BCR-ABL rather than SRC, which is not thought to contribute a major role to the pathogenesis of early chronic phase CML.59,60 There were therefore several potential reasons dasatinib might overcome IM resistance in the stem cell population. First, the increased potency enabled us to test dasatinib at both IC50 (10 nM) and at 15-fold higher concentrations (150 nM)—this could not be achieved with IM without losing Ph+ selectivity and might be sufficient to overcome the increased transcript/kinase activity within the stem cell population. Second, if the balance between active and inactive BCR-ABL conformations is altered in stem cells, then dasatinib should be active as it binds to both conformations equally. Third, if cells expressing kinase domain mutations are enriched at the stem cell level, most of these would be inhibited by dasatinib. And finally, unlike IM, dasatinib is not a substrate for p-Glycoprotein, which may account for it reaching further into the stem cell compartment.61

Dasatinib, at 10 nM, induced significant inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation in CD34+CD38– CML cells at 72 hours as compared to no effect with IM. The level of inhibition of CrKL phosphorylation was greatly enhanced at the higher 150 nM concentration and, encouragingly, was correlated with cell kill, which was higher for dasatinib 150 nM than for dasatinib 10 nM or IM 5 μM. These results certainly suggested that dasatinib was hitting a relevant target(s) further into the stem cell compartment as compared to IM and would therefore be expected to produce lower levels of MRD in vivo.

For many investigators, the “holy grail” is to eradicate those primitive CML stem cells that remain quiescent in the presence of a potent growth factor combination in vitro using a drug(s) that could be applied safely to patients.17,49 CFSE enables high-resolution tracking of cell division within viable cell populations.33-35 Using this assay we were able to show that dasatinib was less antiproliferative, within the stem cell compartment, than IM and is therefore less likely to induce reversible G1 arrest in vitro and potentially in vivo. This is particularly critical when combining drugs that target actively dividing cells. We were, however, disappointed to find that dasatinib was no better than IM in terms of reducing the population of quiescent stem cells in vitro. Although the CFSEmax population was reduced by dasatinib as compared to other drug combinations that included IM, it did not fall below that of the no-drug control, suggesting that dasatinib was able to inhibit CrKL phosphorylation and kill those cells destined to move from G0 to G1, but unable to effect those destined to remain quiescent in culture.

Overall, our results suggest that dasatinib is very much more potent than IM and inhibits BCR-ABL+ cells that are further back into the stem cell compartment. This would be expected to translate to lower levels of MRD in patients. However, the quiescent fraction of stem cells appears to be inherently resistant to IM and to dasatinib. Whether such cells regain sensitivity as they enter cell division is unknown. It also is possible that in such primitive cells, neither BCR-ABL nor SRC are relevant targets, and we will need to develop new stem cell–directed strategies to effectively eradicate these cells in patients.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 9, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2947.

Supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (G84/6317, M.C.), the Leukaemia Research Fund UK (03/20; 04/034; and 04/012, L.J.E., A.H., N.J., M.B.), the Leukaemia Research Trust for Scotland (M.C.), and the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (E.K.A.).

M.C., L.J.E., J.C.M., and T.L.H. participated in designing the research; M.C., L.J.E., A.H., J.W.B., E.K.A., N.J., and M.B. performed the research; M.C., A.H., and J.W.B. analyzed the data; M.C., A.H., J.W.B., E.K.A., and T.L.H. wrote the paper; and all authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank Dr Elisabeth Buchdunger (Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) and Dr Francis Lee (Bristol-Myers Squibb) for providing imatinib and dasatinib, respectively. We are grateful to Dr Graham Templeton for CD34+ cell selection and Mr Peter Broadley for technical assistance. We are indebted to the United Kingdom hematologists who provided leukapheresis samples from their CML patients. We also thank Dr Jaspal Kaeda, Hammersmith Hospital, London, United Kingdom, for providing the plasmids; Dr Susan Branford, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, Adelaide, South Australia, for providing a detailed method and advice about sequencing the abl kinase domain; Dr Michael Deininger and Professor Brian Druker for allowing L.J.E. to visit their laboratory, leading to development of the CrKL phosphorylation assay technique; Dr John Campbell, Miltenyi Biotech, for assistance with the 34/38 selection technique; and, finally, Drs Connie Eaves, Xiaoyan Jiang, and Ravi Bhatia for useful discussions.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal