Abstract

Bone destruction in multiple myeloma is characterized both by markedly increased osteoclastic bone destruction and severely impaired osteoblast activity. We reported that interleukin-3 (IL-3) levels are increased in bone marrow plasma of myeloma patients compared with healthy controls and that IL-3 stimulates osteoclast formation. However, the effects of IL-3 on osteoblasts are unknown. Therefore, to determine if IL-3 inhibits osteoblast growth and differentiation, we treated primary mouse and human marrow stromal cells with IL-3 and assessed osteoblast differentiation. IL-3 inhibited basal and bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2)-stimulated osteoblast formation in a dose-dependent manner without affecting cell growth. Importantly, marrow plasma from patients with high IL-3 levels inhibited osteoblast differentiation, which could be blocked by anti-IL-3. However, IL-3 did not inhibit osteoblast differentiation of osteoblastlike cell lines. In contrast, IL-3 increased the number of CD45+ hematopoietic cells in stromal-cell cultures. Depletion of the CD45+ cells abolished the inhibitory effects of IL-3 on osteoblasts, and reconstitution of the cultures with CD45+ cells restored the capacity of IL-3 to inhibit osteoblast differentiation. These data suggest that IL-3 plays a dual role in the bone destructive process in myeloma by both stimulating osteoclasts and indirectly inhibiting osteoblast formation. (Blood. 2005;106:1407-1414)

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B-cell malignancy characterized by an accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM). Bone destruction is a major source of morbidity in patients with MM. Symptoms due to bone destruction in MM include bone pain, pathologic fractures, and hypercalcemia.1

In advanced MM, normal bone remodeling is uncoupled, with bone destruction no longer linked to new bone formation.2 Thus, MM bone destruction is caused by both increased osteoclast (OCL) numbers and activity with a concomitant decrease in osteoblastic (OBL) bone formation. In early stages of the disease (stages I and II), an increase in OCL number does result in a proportional increase in OBL number. However, even in early stages, the increase in OBL number is not associated with a relative increase in OBL function. A 3-fold increase in OCL and OBL number is associated with only a 1.5-fold increase in bone formation, leading to net bone loss due to loss of OBL functional capacity. In the advanced stage of disease (stage III), the amount of eroded bone surface is increased, but the number of osteoclasts is not significantly increased compared with stage II disease. This is caused by an uncoupling of bone remodeling such that OBL number and functional capacity are both decreased relative to the increased number of osteoclasts.2

The factors involved in mediating OCL activation in MM have been a subject of intense investigation. Factors such as receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) have been implicated as OCL activators in MM.3 In contrast to OCL stimulators, the basis for the decreased OBL activity in MM bone disease has not been clearly defined. Tian et al recently reported that Dickkopf1 (DKK1), an inhibitor of the WNT signaling pathway that is involved in osteoblastogenesis, is produced by myeloma cells.4 DKK1 gene expression levels correlated with the extent of bone disease in MM. Surprisingly, DKK1 expression was not increased in patients with a more aggressive type of myeloma.4 Other potential OBL inhibitors that have been suggested are IL-11, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 4 (IGF-BP4), and soluble Frizzled related protein-2 (sFRP-2). IL-11, which is increased in a subset of MM patients and may block new bone formation, is thought to be secreted from the osteoblasts themselves.5 IGF-BP4 is also produced by MM cells and may inhibit IGF-1-stimulated OBL growth.6 However, neither of these factors is produced by most MM patients. sFRP-2 and sFRP-3, other inhibitors of the wnt signaling pathway, have also been reported in preliminary studies to be produced by myeloma cells and partially block OBL differentiation in the murine OBL-like cell line, MC3T3-E1.7

We recently reported that IL-3 levels in BM plasma from patients with MM are increased in approximately 70% of patients compared with healthy controls. We demonstrated that IL-3 increased OCL formation and MM cell growth in vitro.8 In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that cytokines overexpressed in the MM marrow microenvironment, which are implicated in OCL bone destruction (eg, RANKL, MIP-1α, and IL-3), may also inhibit OBL differentiation in MM. In this report, we show that IL-3 inhibited OBL differentiation in vitro in both mouse and human primary OBL cultures and that IL-3 blocked differentiation of preosteoblasts to mature osteoblasts in vitro at concentrations comparable to those seen in marrow plasma from patients with MM. Importantly, BM plasma from patients with MM with high levels of IL-3 blocked OBL formation in human cultures, and this inhibition was partially reversed with the addition of a neutralizing antibody to human IL-3. We further found that the inhibitory effects of IL-3 were increased in the presence of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a cytokine induced in the MM marrow microenvironment,3 and that the effects of IL-3 were not through increased expression of TNF-α. Interestingly, we found that the effects of IL-3 were indirect and were mediated by CD45+/CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages in both human and mouse primary culture systems. Taken together, these data support a dual role for IL-3 in MM bone disease, acting as both a stimulator of OCL formation and an inhibitor of OBL differentiation.

Materials and methods

α-Minimum essential medium (α-MEM), trypsin/EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), reverse transcriptase, Taq DNA polymerase, and 10 × PCR Enhancer were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, Triton X-100, Alkaline Phosphatase Yellow (pNPP) Liquid Substrate system for ELISA, Bradford reagent, silver nitrate, and sodium thiosulfate were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Fetal calf serum (FCS) for murine cultures was purchased from JRH Biosciences (Lenexa, KS). RNA-Bee was purchased from Tel-Test (Friendswood, TX). Anti-mouse β-catenin (C-18) and anti-mouse actin (C-11) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). MTT (3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium) assay was from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Recombinant mouse IL-3, recombinant human TNF-α, recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2), goat antimouse neutralizing antibody, and mouse TNF-α ELISA kit were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Antiphycoerythrin (anti-PE) and anti-fluorescein isothiocyanate (anti-FITC) MicroBeads and LD columns were from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). PE-conjugated anti-CD45 and FITC-conjugated anti-CD3, anti-CD11b, and anti-CD19 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). B6D2F1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

Primary human CFU-F and CFU-OB cultures and osteoblast progenitors (pre-OBs)

Human BM mononuclear cells were obtained from healthy subjects by aspiration from the iliac crest and were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density sedimentation. These studies were approved by the Human Studies committee at the Università delgi Studi di Parma and the University of Pittsburgh. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. BM cells were seeded in 6-well plates at the density of 106 per well in 4 mL α-MEM with 15% FCS plus ascorbic acid (50 μg/mL) and dexamethasone (10-8 M) and cultured with or without recombinant human IL-3 (rhIL-3) (Endogen, Woburn, MA) (20 pg/mL to 20 ng/mL) or with BM plasma obtained from MM patients (dilution 1:3) in the presence or absence of blocking anti-IL-3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (1 μg/mL) (R&D Systems). BM cultures were maintained for 14 days for fibroblast colony-forming unit (CFU-F) formation or for 21 days for osteoblast CFUs (CFU-OBs). In CFU-OB cultures, β-glycerophosphate (10 mM) was added to the cultures. Half of the media was replaced with fresh media every 3 days. For CFU-F evaluation, after 14 days of culture, the cells were fixed with cold formalin at 4°C, washed 3 times with PBS, and stained with an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) semiquantitative histochemical kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's procedures. Each colony was defined by the presence of at least 50 ALP-positive cells. Quantification of ALP staining was performed using 1D Image Analysis Software (Kodak Digital Science, Rochester, NY). For CFU-OB evaluation, cells were fixed with a 1:1 mixture (vol/vol) of 37% formaldehyde and ethanol for 5 minutes, washed 3 times with PBS, and stained for 10 minutes with a solution of 2% of Alizarin Red (Sigma Aldrich) at pH 4.2. Colonies were quantified by direct counting of all stained bone nodules positive for Alizarin Red using light microscopy.

Human preosteoblastic cells (pre-OBs) were obtained from primary BM adherent cells after attachment for 3 to 5 days, and then the adherent cells were incubated in α-MEM with 15% FCS and 2 mM glutamine in the presence of ascorbic acid (50 μg/mL) and dexamethasone (10-8M) for 2 weeks. Confluent pre-OBs were incubated in the presence or the absence of rhIL-3 (20 pg/mL to 20 ng/mL) for 1 to 7 days.

Primary mouse stromal-cell cultures

Primary stromal cells were obtained from 4- to 6-week-old B6D2F1 mice. Whole marrow was flushed from hind-limb long bones and plated in α-MEM with 10% FCS. Marrow from 2 mice was plated per 10-cm dish. After 4 days, nonadherent cells were discarded and adherent cells were washed with media and removed with trypsin/EDTA. Cells were split 1:2 and replated for 4 days in α-MEM with 10% FCS. This cell population, which has been reported to be stromal-cell enriched and monocyte depleted,9 was used for further experimentation.

Stromal cells were plated at 104 cells per well in a 48-well plate with 0.5 mL osteogenic media with or without additional cytokines. The osteogenic media were α-MEM with 10% FCS, 50 mg/L ascorbic acid, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. Media were replaced every 3 days with fresh osteogenic media with or without additional cytokines. After 10 days of culture the cells were assayed for ALP activity as described in “Alkaline phosphatase assay.” After 3 weeks in culture, the mineral deposition was determined by the von Kossa method as described in “von Kossa staining.”

Alkaline phosphatase assay

Murine stromal cells cultured for 10 days in osteogenic media were washed 2 times with PBS and lysed with 200 μL 0.1% Triton X-100 using one freeze-thaw cycle (-80°C) to ensure complete cell lysis. The cell lysates were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 15 000g (12 000 rpm) for 3 minutes at 4°C to clear cellular debris. A total of 50 μL cell lysate was transferred to a 96-well plate, and 150 μL room-temperature pNPP was added to each well. Optical density at 405 nm was read at time 0 and 30 minutes afterward and the zero value subtracted from the 30-minute value to assess activity. ALP activity levels were reported as micromoles of pNPP hydrolyzed per minute per well corrected as percent control. ALP in cell lines was corrected for protein and was reported as micromoles of pNPP hydrolyzed per minute per microgram of protein and was corrected as percent control.

von Kossa staining (for mineral deposition)

Murine stromal cells cultured for 3 weeks in osteogenic media were washed with cold PBS and fixed in 10% formalin for 15 minutes. Cells were then washed 3 times with deionized water, leaving the final wash on for 15 minutes; 200 μL of 5% silver nitrate was added to each well. The plates were kept in the dark for 15 minutes and then exposed to room light for 1 to 2 hours until the stained areas turned dark brown/black. Cells were then extensively washed with deionized water; 250 μL of 5% sodium thiosulfate was added for 2 minutes to remove nonspecific staining. Cells were again washed 3 times with deionized water and allowed to air dry. Wells with von Kossa-positive staining were scanned and imported into Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Histogram values were obtained from each well, and background levels were subtracted.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells with the use of RNA-Bee according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNAs were precipitated with isopropanol, and the pellets washed with 70% ethanol, briefly air dried, dissolved in water, and stored at -80°C. Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR analyses were performed using the PerkinElmer (Branchburg, NJ) PCR apparatus. After reverse transcription, the PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C or 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute for 20 to 35 cycles depending on the relative amount of PCR products for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) detected, which was used as an internal control with the same PCR conditions. PCR for IL-3Rα required the addition of 2 × PCR Enhancer. The PCR primers for murine IL-3Rα, ALP (ALP), osteocalcin (OC), and GAPDH are listed in Table 1. PCR primers for human IL-3, IL-3Rα, and GAPDH are listed in Table 2. The PCR products were sequence analyzed to confirm their identity. Bands were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and corrected for GAPDH levels.

Murine PCR primers

Gene . | Sequence . | Size, bp . | Annealing temperature, °C . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-3Rα | 636 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-TGC ACT ACC GGA TGT TCT GG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-ACT TCC TCC ACC ACA GCA GG-3′ | ||

| ALP | 517 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-AAC CCA GAC ACA AGC ATT CC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GAG ACA TTT TCC CGT TCA CC-3′ | ||

| OC | 430 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-GCA GCT TGG TGC ACA CCT AG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GGA GCT GCT GTG ACA TCC ATA C-3′ | ||

| Runx2 | 308 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-CCC AGC CAC CTT TAC CTA CA-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-CAG CGT CAA CAC CAT CAT TC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | 451 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′ |

Gene . | Sequence . | Size, bp . | Annealing temperature, °C . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-3Rα | 636 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-TGC ACT ACC GGA TGT TCT GG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-ACT TCC TCC ACC ACA GCA GG-3′ | ||

| ALP | 517 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-AAC CCA GAC ACA AGC ATT CC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GAG ACA TTT TCC CGT TCA CC-3′ | ||

| OC | 430 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-GCA GCT TGG TGC ACA CCT AG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GGA GCT GCT GTG ACA TCC ATA C-3′ | ||

| Runx2 | 308 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-CCC AGC CAC CTT TAC CTA CA-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-CAG CGT CAA CAC CAT CAT TC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | 451 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′ |

Human PCR primers

Gene . | Sequence . | Size, bp . | Annealing temperature, °C . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-3 | 441 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-CTT CAA CAA CCT CAA TGG GG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-AAT TCA TCT GAT GCC GCA GG-3′ | ||

| IL-3R | 555 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-TCT CCA GCG GTT CTC AAA GTT CCC ACA TCC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-CCC AGA CCA CCA GCT TGT CGT TTT GGA AGC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | 209 | 58 | |

| Sense | 5′-CAA CGG ATT TGG TCG TAT TG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GGA AGA TGG TGA TGG GAT TT-3′ |

Gene . | Sequence . | Size, bp . | Annealing temperature, °C . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-3 | 441 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-CTT CAA CAA CCT CAA TGG GG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-AAT TCA TCT GAT GCC GCA GG-3′ | ||

| IL-3R | 555 | 60 | |

| Sense | 5′-TCT CCA GCG GTT CTC AAA GTT CCC ACA TCC-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-CCC AGA CCA CCA GCT TGT CGT TTT GGA AGC-3′ | ||

| GAPDH | 209 | 58 | |

| Sense | 5′-CAA CGG ATT TGG TCG TAT TG-3′ | ||

| Antisense | 5′-GGA AGA TGG TGA TGG GAT TT-3′ |

Electromobility shift assays (EMSAs)

Human Runx2 gel mobility shift assays were performed using a Nushift AML-3/Runx2 kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, Runx2/Cbfa1 binding consensus oligonucleotide probes (osteoblast-specific element 2 [OSE2]: 5′-AGCTGCAATCACCAACCACAGCA-3′) were annealed by heating to 95°C and cooling to 25°C in 50 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)-HCl (pH 8.2), 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EDTA; end-labeled with [32P]deoxycytidine triphosphate ([32P]dCTP); and purified through a G-25 purification column (Active Motif). Nuclear extracts (20 μg) were incubated on ice for 10 minutes in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid]-HCl, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA], 50 μg/mL poly(dI/dC), and 20% glycerol, pH 7.9) with 10 fmol (2 × 104 cpm) of 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes in a total volume of 20 μL. In competitive binding reactions, unlabeled wild-type oligonucleotide was added before the 32P-labeled probe. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved in 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in Tris-glycine buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3) at 20°C, 25 mA, and 200 V for 1.5 hours. Supershift experiments contained 0.2 μg Runx2/Cbfa1 polyclonal rabbit antibody supplied with the kit. Gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography.

Western blot

For human cultures, nuclear and cytosolic extracts were prepared using the Nuclear Extraction Kit (Active Motif) according to manufacturer's protocol. Protein concentrations were determined using a standard procedure (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After 40 minutes on ice, lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 12 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Proteins (40 to 70 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal anti-β-catenin mAb (1:1000) (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) or β-actin mAb (1:500) (Sigma Aldrich). After washing, membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antimouse Ab (1:10 000) (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) or antigoat Ab (1:30 000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Blots were then developed using the standard ECLplus protocol (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by a 5- to 15-minute exposure (Kodak X-OMAT; Kodak).

For murine cultures, whole cell extracts were prepared by adding 200 μL SDS gel loading buffer to each well of a confluent 6-well plate and separated by SDS-PAGE on 8% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk, blots were incubated with anti-β-catenin (1:100) (C-18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C, followed by antigoat immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to HRP (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and visualized by chemiluminescence on x-ray film. Antiactin-HRP (1:2000) (C-11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as an internal control on the same membrane after stripping the anti-β-catenin Ab.

CD45+ cell depletion

Primary mouse or human BM cells were washed 2 times with PBS. Then 106 cells were resuspended in 45 μL PBS, and 5 μL PE-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody was added. The suspensions were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C and then washed with bead buffer (PBS with 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA). Cells were resuspended in 80 μL, and 20 μL anti-CD45 bound magnetic beads was added. Cells were incubated with the beads for 30 minutes at 4°C. Columns were wetted with buffer and placed under a magnetic field (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec). Cells bound to beads were added to the columns, and 2 column volumes of buffer were added to obtain a flow-through containing CD45-depleted cell population. Nonspecific primary antibody bound beads were used as a control. CD45-depleted cells were counted and plated at 104 cells per well in a 48-well plate as usual with or without cytokines. After 10 days of culture, ALP activity was determined as described in “Alkaline phosphatase assay.” Efficiency of depletion was determined by flow cytometry as described in “Flow cytometry.”

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out as previously described.10 Preparations of 106 or fewer cells were incubated with FITC- or PE-conjugated mAbs or isotype controls for 20 minutes at 4°C and then washed with PBS. Labeled cells were resuspended in PBS for flow analysis. Samples were collected using FACSort (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Four parameters were analyzed: forward scatter, side scatter, and the two parameters of 2-color fluorescence intensity, PE and FITC. Regions were set using forward versus side scatter; 10 000 events were collected for each sample.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation for typical experiments done in 3 or 4 replicate samples and were compared by the Student t test. Results were considered significantly different for P < .05. All experiments were performed at least 3 times to ensure reproducibility of the results.

Results

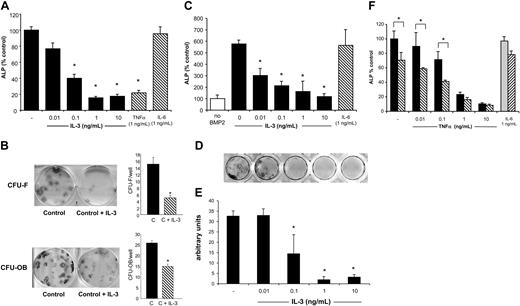

Because the effects of IL-3 are species specific, we determined if IL-3 affected OBL differentiation of both human and murine stromal cells to determine the generalized effects and to eventually assess the effects of IL-3 in murine models of myeloma in vivo. Therefore, to determine if OBL precursors could respond to IL-3, IL-3Rα expression was measured by RT-PCR and flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1, primary murine stromal cells/osteoblasts obtained after 8 days of culture and induced to differentiate along the OBL lineage with the addition of osteogenic media for 10 days expressed IL-3Rα mRNA (Figure 1A). Similarly, both mature human osteoblasts (HOBIT) and human primary marrow cultures after 2 to 3 weeks of differentiation also expressed IL-3Rα mRNA in vitro (Figure 1B). Expression of IL-3R was confirmed at protein level by Western blot analysis and flow cytometry (data not shown). Because OBL cells expressed IL-3R, we determined the effects of IL-3 on the capacity of these cultures to differentiate into osteoblasts. Murine stromal-cell/OBL cultures treated for 10 days with osteogenic media expressed ALP (ALP), a marker of OBL differentiation.11 ALP activity was dose-dependently decreased in murine stromal-cell cultures by the addition of murine IL-3 (Figure 2A). Maximum inhibition of ALP activity was reached in cultures treated with 1 ng/mL IL-3, which inhibited ALP expression by approximately 80%. Importantly, the dose required to significantly inhibit ALP, 100 pg/mL, was the mean level present in BM plasma of patients with MM.8 Another cytokine implicated in myeloma, IL-6,3 had no effect on OBL differentiation, while the known OBL inhibitor, TNF-α,9,12 also inhibited OBL differentiation in these cultures.

IL-3Rα is expressed in primary mouse and human OBL/stromal cells. (A) Murine stromal cells were grown for 10 days in either α-MEM (control) or osteogenic media (OBL induction). RNA was isolated, and expression of murine IL-3Rα was examined by RT-PCR analysis. The identity of the band as IL-3Rα was confirmed by direct sequencing. (B) Human BM adherent cells were cultured for 1, 2, or 3 weeks in osteogenic media as described in “Materials and methods.” Human IL-3Rα and IL-3 mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR using specific primer pairs.

IL-3Rα is expressed in primary mouse and human OBL/stromal cells. (A) Murine stromal cells were grown for 10 days in either α-MEM (control) or osteogenic media (OBL induction). RNA was isolated, and expression of murine IL-3Rα was examined by RT-PCR analysis. The identity of the band as IL-3Rα was confirmed by direct sequencing. (B) Human BM adherent cells were cultured for 1, 2, or 3 weeks in osteogenic media as described in “Materials and methods.” Human IL-3Rα and IL-3 mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR using specific primer pairs.

We then tested the effects of IL-3 on human OBL differentiation. CFU-Fs and CFU-OBs were obtained by culture of human BM aspirates maintained for 14 days or 21 days in OBL differentiation media, respectively. Both CFU-Fs and CFU-OBs were significantly inhibited by IL-3 with a maximal effect at 20 ng/mL (CFU-F versus control: - 70%; CFU-OB versus control: - 40%; P < .05) (Figure 2B).

We then determined if IL-3 could inhibit OBL differentiation in the presence of a potent OBL differentiating agent. The addition of BMP-2 to the osteogenic media in primary murine OBL cultures induced OBL differentiation with an increase in ALP expression at 10 days that was 6-fold greater than osteogenic media alone. IL-3 (0.01 to 10 ng/mL) was still capable of inhibiting OBL differentiation even in the presence of BMP-2 (Figure 2C). After 3 weeks in culture, primary OBL cultures were stained for mineral deposition by the von Kossa method. Mineral deposition by differentiated osteoblasts was also blocked by IL-3 (Figure 2D-E). Mineralization was also decreased in a dose-dependent manner at IL-3 concentrations detectable in marrow plasma from patients with MM.

Differentiation of osteoblasts from immature precursors to mature osteoblasts and finally to osteocytes is characterized by a distinct gene expression profile. Osteoblasts initially express high levels of ALP early and low levels of OC. In contrast, OC is expressed at high levels in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes.11 Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that IL-3 inhibited both ALP and OC mRNA expression in murine stromal-cell cultures (Figure 3A), consistent with our cell-culture results. Interestingly, IL-3 did not inhibit expression of Runx2 mRNA, a transcription factor required for OBL differentiation.13 A functional assay of Runx2 binding to its DNA binding site by electromobility shift assay (EMSA) also showed that IL-3 did not affect Runx2 activity in human pre-OB cells after 1 to 7 days (Figure 3B), indicating that IL-3 does not directly inhibit OBL differentiation through Runx2-induced transcription. DKK1, a mediator of the β-catenin pathway, has been implicated in MM bone disease.4 Protein levels of β-catenin, the downstream effector of DKK1,14 were unchanged by IL-3 treatment of human pre-OB and mouse OBL cultures (Figure 3C), indicating that IL-3 does not block the β-catenin pathway.

To test the potential involvement of IL-3 in the inhibition of OBL bone formation in MM, we determined the effects of BM plasma obtained from MM patients on OBL differentiation. BM plasma with low and higher IL-3 levels (range, less than 5 pg/mL or greater than 80 pg/mL) were tested. BM plasma significantly inhibited CFU-F formation in BM cultures (Figure 4). The addition of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to IL-3 significantly decreased the inhibitory effects of BM plasma from patients with high IL-3 (more than 50 pg/mL) on CFU-F formation but had no effect on BM plasma with low IL-3 levels (Figure 4). A similar effect was observed on CFU-OB formation (data not shown).

To determine if the inhibition of OBL differentiation by IL-3 could be enhanced by other cytokines present at low levels in the myeloma microenvironment, we tested the combination of TNF-α (0.01 to 10 ng/mL) and IL-3 on stromal-cell cultures. As shown in Figure 2E, low concentrations of TNF-α increased the inhibitory effect of IL-3 on OBL differentiation compared with TNF-α alone. We added 100 pg/mL IL-3 to cultures treated with increasing concentrations of TNF-α (0.01 to 10 ng/mL). At low levels of TNF-α (0.01 to 0.1 ng/mL), IL-3 and TNF-α had an additive effect on lowering ALP expression. At higher levels of TNF-α, ALP was fully inhibited, and no additional effects of IL-3 were seen.

Because primary marrow stromal-cell cultures are a mixed cell population, we then determined if IL-3 was directly inhibiting OBL differentiation by testing the effects of IL-3 on preosteoblast cell lines. When MC3T3-E1 cells, which are derived from mouse calvarial osteoblasts,15 or the C2C12 myoblastic cells16 were induced to express ALP with BMP-2, the addition of IL-3 did not block ALP expression (Figure 5A). In contrast, TNF-α inhibits ALP levels in MC3T3-E1 and C2C12 cells (data not shown).

OBL differentiation is inhibited by IL-3. (A) Primary mouse OBL cells were cultured for 10 days in osteogenic media with or without the addition of IL-3 (0.01 to 10 ng/mL), TNF-α (1 ng/mL), or IL-6 (1 ng/mL). ALP activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” ALP activity was decreased in a dose-dependant manner by the presence of IL-3. TNF-α and IL-6 are positive and negative controls, respectively. ALP activity in the untreated control ranged from 40 to 70 mU per 104 cells plated. Inhibition by IL-3 ranged from 50% to 80% of control. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (B) Primary human BM adherent cells were cultured for 10 days (CFU-F) or 21 days (CFU-OB) in osteogenic media and treated with IL-3 (0.02 to 20 ng/mL). Alkaline phosphatase and Alizarin Red staining was performed after that culture period, respectively, and the colonies were counted and quantified. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation of the number of CFU-Fs and CFU-OBs in 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (C) Cells were treated for 10 days with osteogenic media supplemented with BMP-2 (50 ng/mL) with or without IL-3, and ALP activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” BMP-2 alone stimulated ALP expression and was blocked by IL-3. IL-6 is a negative control. (D) Primary murine OBL cells were cultured for 3 weeks in osteogenic media with or without the addition of IL-3 and then stained for mineral deposition by the von Kossa method as described in “Materials and methods.” Mineral deposition was inhibited in response to IL-3. Shown is a representative well from each concentration. (E) The culture plate from panel D was scanned and quantified for relative amount stained using Adobe Photoshop. Quantification of von Kossa staining shows a dose-dependent decrease in amount stained in response to IL-3. (F) IL-3 increases the capacity of TNF-α to inhibit OBL differentiation. Primary murine OBL cultures were treated with osteogenic media and increasing amounts of TNF-α (0.01 to 10 ng/mL) without (▪) or with (▧) IL-3 (100 pg/mL). IL-6 treatment with ( ) or without (▧) IL-3 is a negative control. ALP activity was determined as described in “Materials and methods.” In all panels, data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

) or without (▧) IL-3 is a negative control. ALP activity was determined as described in “Materials and methods.” In all panels, data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

OBL differentiation is inhibited by IL-3. (A) Primary mouse OBL cells were cultured for 10 days in osteogenic media with or without the addition of IL-3 (0.01 to 10 ng/mL), TNF-α (1 ng/mL), or IL-6 (1 ng/mL). ALP activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” ALP activity was decreased in a dose-dependant manner by the presence of IL-3. TNF-α and IL-6 are positive and negative controls, respectively. ALP activity in the untreated control ranged from 40 to 70 mU per 104 cells plated. Inhibition by IL-3 ranged from 50% to 80% of control. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (B) Primary human BM adherent cells were cultured for 10 days (CFU-F) or 21 days (CFU-OB) in osteogenic media and treated with IL-3 (0.02 to 20 ng/mL). Alkaline phosphatase and Alizarin Red staining was performed after that culture period, respectively, and the colonies were counted and quantified. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation of the number of CFU-Fs and CFU-OBs in 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. (C) Cells were treated for 10 days with osteogenic media supplemented with BMP-2 (50 ng/mL) with or without IL-3, and ALP activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” BMP-2 alone stimulated ALP expression and was blocked by IL-3. IL-6 is a negative control. (D) Primary murine OBL cells were cultured for 3 weeks in osteogenic media with or without the addition of IL-3 and then stained for mineral deposition by the von Kossa method as described in “Materials and methods.” Mineral deposition was inhibited in response to IL-3. Shown is a representative well from each concentration. (E) The culture plate from panel D was scanned and quantified for relative amount stained using Adobe Photoshop. Quantification of von Kossa staining shows a dose-dependent decrease in amount stained in response to IL-3. (F) IL-3 increases the capacity of TNF-α to inhibit OBL differentiation. Primary murine OBL cultures were treated with osteogenic media and increasing amounts of TNF-α (0.01 to 10 ng/mL) without (▪) or with (▧) IL-3 (100 pg/mL). IL-6 treatment with ( ) or without (▧) IL-3 is a negative control. ALP activity was determined as described in “Materials and methods.” In all panels, data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

) or without (▧) IL-3 is a negative control. ALP activity was determined as described in “Materials and methods.” In all panels, data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

IL-3 inhibits ALP and OC mRNA expression, early and late markers of OBL differentiation into osteocytes, but the inhibitory effects of IL-3 were not mediated by the Runx2 or β-catenin pathways. (A) RNA was isolated from primary murine stromal cells cultured for 10 days with increasing concentrations of IL-3. RT-PCR was performed with primers specific for murine ALP, OC, and Runx2. IL-6 was a negative control for ALP, OC, and Runx2 response. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (B) Primary human confluent pre-OB cells were treated with IL-3 (20 ng/mL) for 1 to 7 days. After the culture period, cell lysates were obtained and nuclear extracts were separated from the cytosolic fraction. Runx2 activity evaluation was determined by EMSA on nuclear extracts as described in “Materials and methods.” IL-3 did not change Runx2 activity in human cultures. Lysates were obtained after 24 hours or 7 days of IL-3 treatment in human stromal-cell cultures. (C) Whole cell lysates from human stromal-cell cultures treated with IL-3 for 24 hours or 7 days or from murine cultures for 24 hours or 6 days were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis for β-catenin expression. β-actin served as an internal control.

IL-3 inhibits ALP and OC mRNA expression, early and late markers of OBL differentiation into osteocytes, but the inhibitory effects of IL-3 were not mediated by the Runx2 or β-catenin pathways. (A) RNA was isolated from primary murine stromal cells cultured for 10 days with increasing concentrations of IL-3. RT-PCR was performed with primers specific for murine ALP, OC, and Runx2. IL-6 was a negative control for ALP, OC, and Runx2 response. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (B) Primary human confluent pre-OB cells were treated with IL-3 (20 ng/mL) for 1 to 7 days. After the culture period, cell lysates were obtained and nuclear extracts were separated from the cytosolic fraction. Runx2 activity evaluation was determined by EMSA on nuclear extracts as described in “Materials and methods.” IL-3 did not change Runx2 activity in human cultures. Lysates were obtained after 24 hours or 7 days of IL-3 treatment in human stromal-cell cultures. (C) Whole cell lysates from human stromal-cell cultures treated with IL-3 for 24 hours or 7 days or from murine cultures for 24 hours or 6 days were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis for β-catenin expression. β-actin served as an internal control.

OBL inhibition by MM marrow plasma is reversed by anti-IL-3 neutralizing antibody in patients with high IL-3 and unaffected in patients with normal IL-3 in CFU-F cultures. BM stromal-cell cultures were treated with BM plasma from patients with high IL-3 (more than 50 pg/mL; MM1) or normal IL-3 (less than 5 pg/mL; MM2) without (▪) or with (▧) anti-IL-3 mAb (1 μg/mL). After 14 days of culture, ALP staining was performed and quantified by 1D Image Analysis Software (Kodak Digital Science). Data represent the average ± standard deviation of 3 wells for each condition for a typical experiment.

OBL inhibition by MM marrow plasma is reversed by anti-IL-3 neutralizing antibody in patients with high IL-3 and unaffected in patients with normal IL-3 in CFU-F cultures. BM stromal-cell cultures were treated with BM plasma from patients with high IL-3 (more than 50 pg/mL; MM1) or normal IL-3 (less than 5 pg/mL; MM2) without (▪) or with (▧) anti-IL-3 mAb (1 μg/mL). After 14 days of culture, ALP staining was performed and quantified by 1D Image Analysis Software (Kodak Digital Science). Data represent the average ± standard deviation of 3 wells for each condition for a typical experiment.

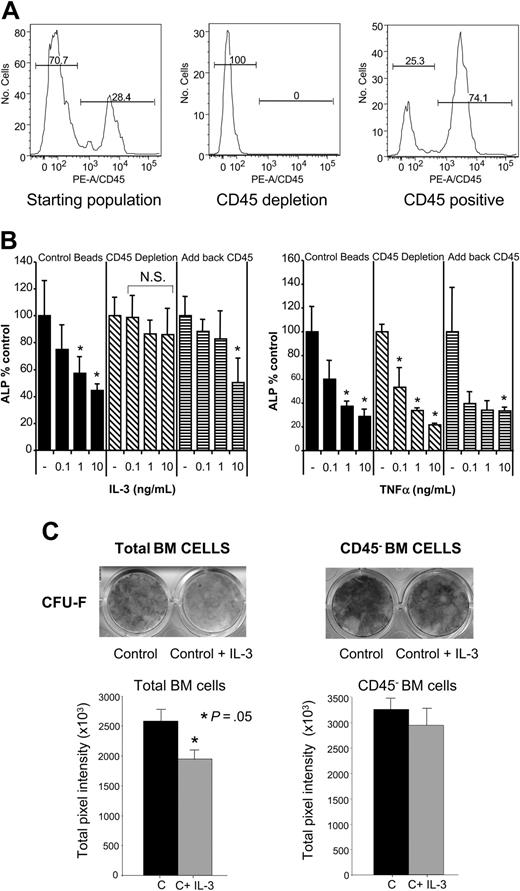

To exclude that IL-3 was simply toxic to the cultures and thus inhibiting OBL differentiation, cell growth was measured by the MTT assay. IL-3 did not induce cell death or block cell growth at low concentrations (Figure 5B) in murine stromal-cell cultures, and at high concentrations (1 to 10 ng/mL) cell number was increased. We then determined if IL-3 was affecting the cell-type distribution in the primary cultures, particularly the percentage of hematopoietic cells because IL-3 stimulates growth of hematopoietic cells.17 Therefore, flow cytometry studies were performed to determine the percentage of CD45+ cells, a marker for hematopoietic cells,18 that is not expressed on OBL cells in the cultures.19,20 As shown in Figure 6A, 30% of the cells in murine stromal-cell/OBL cultures were CD45+ cells.

IL-3 does not inhibit ALP levels in osteoblastlike cell lines MC3T3-E1 and C2C12 and increases cell number in primary murine cultures. (A) MC3T3-E1 or C2C12 cells were treated with 50 ng/mL BMP-2 to stimulate OBL differentiation and increasing concentrations of IL-3 (0.1 to 10 ng/mL). ALP levels measured at 10 days were corrected for protein content, and are represented as percent control cultures (without BMP-2 stimulation). (B) Cell number in primary murine cultures was determined by the MTT assay after a 10-day culture of primary OBL cells with or without the addition of IL-3. Low concentrations of IL-3 (0.01 to 0.1 ng/mL) did not decrease cell number. High concentrations of IL-3 (more than 1 pg/mL) increased cell number. Data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

IL-3 does not inhibit ALP levels in osteoblastlike cell lines MC3T3-E1 and C2C12 and increases cell number in primary murine cultures. (A) MC3T3-E1 or C2C12 cells were treated with 50 ng/mL BMP-2 to stimulate OBL differentiation and increasing concentrations of IL-3 (0.1 to 10 ng/mL). ALP levels measured at 10 days were corrected for protein content, and are represented as percent control cultures (without BMP-2 stimulation). (B) Cell number in primary murine cultures was determined by the MTT assay after a 10-day culture of primary OBL cells with or without the addition of IL-3. Low concentrations of IL-3 (0.01 to 0.1 ng/mL) did not decrease cell number. High concentrations of IL-3 (more than 1 pg/mL) increased cell number. Data are represented as average ± standard deviation for 4 wells for each concentration and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

CD45+-cell depletion from primary OBL cultures blocks the inhibitory effects of IL-3. (A) Murine BM was cultured in α-MEM plus 10% FCS media for 8 days as described in “Materials and methods.” These cells were the starting population for further OBL differentiation studies. Flow cytometry analysis shows a PE-CD45- population of approximately 70% and a PE-CD45+ population of 30%. CD45+ cells were then depleted from the total population by magnetic bead depletion as described in “Materials and methods.” The resulting population was essentially 100% CD45- by flow cytometry. The CD45+-enriched population was recovered after depletion and was approximately 25% CD45- and 75% CD45+. (B) The CD45-depleted or reconstituted cell populations or control cells were plated as usual in osteogenic media with varying concentrations of IL-3 or TNF-α (0.1 to 10 ng/mL), and ALP activity was determined as usual after 10 days in culture. ▪ represents cells depleted with a nonspecific IgG primary antibody; ▧, CD45-depleted cells; and ▤, CD45-depleted cultures reconstituted with CD45+ cells. Depleting CD45+ cells results in a cleaner stromal-cell/OBL population, so the ALP level per well was approximately 2 times control antibody depletion. Data are represented as percent of media alone (without IL-3 treatment) for each group and are mean ± standard deviation for 3 wells for each concentration for a typical experiment. Similar results were seen in 2 independent experiments. *P < .05; N.S. indicates not significant. (C) CD45+ cells were depleted from human BM cell cultures by immunomagnetic method using coated anti-CD45 microbeads and treated with IL-3 (20 ng/mL) for the entire culture period. Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed after 14 days and quantified by 1D Image Analysis Software (Kodak Digital Science). CD45+ cell depletion resulted in loss of the IL-3 inhibitory effects in CFU-F cultures. Data represent the average ± standard deviation of 3 wells for each condition for a typical experiment.

CD45+-cell depletion from primary OBL cultures blocks the inhibitory effects of IL-3. (A) Murine BM was cultured in α-MEM plus 10% FCS media for 8 days as described in “Materials and methods.” These cells were the starting population for further OBL differentiation studies. Flow cytometry analysis shows a PE-CD45- population of approximately 70% and a PE-CD45+ population of 30%. CD45+ cells were then depleted from the total population by magnetic bead depletion as described in “Materials and methods.” The resulting population was essentially 100% CD45- by flow cytometry. The CD45+-enriched population was recovered after depletion and was approximately 25% CD45- and 75% CD45+. (B) The CD45-depleted or reconstituted cell populations or control cells were plated as usual in osteogenic media with varying concentrations of IL-3 or TNF-α (0.1 to 10 ng/mL), and ALP activity was determined as usual after 10 days in culture. ▪ represents cells depleted with a nonspecific IgG primary antibody; ▧, CD45-depleted cells; and ▤, CD45-depleted cultures reconstituted with CD45+ cells. Depleting CD45+ cells results in a cleaner stromal-cell/OBL population, so the ALP level per well was approximately 2 times control antibody depletion. Data are represented as percent of media alone (without IL-3 treatment) for each group and are mean ± standard deviation for 3 wells for each concentration for a typical experiment. Similar results were seen in 2 independent experiments. *P < .05; N.S. indicates not significant. (C) CD45+ cells were depleted from human BM cell cultures by immunomagnetic method using coated anti-CD45 microbeads and treated with IL-3 (20 ng/mL) for the entire culture period. Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed after 14 days and quantified by 1D Image Analysis Software (Kodak Digital Science). CD45+ cell depletion resulted in loss of the IL-3 inhibitory effects in CFU-F cultures. Data represent the average ± standard deviation of 3 wells for each condition for a typical experiment.

To determine if IL-3 acted through hematopoietic cells to inhibit OBL differentiation, CD45+ cells were depleted from both human BM and murine stromal-cell cultures, and their response to IL-3 was determined. CD45+ cells were removed from the stromal-cell cultures by binding the CD45+ cells to a PE-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody and then, using magnetic beads linked to an anti-PE antibody, depleted on cell separation columns. A nonspecific PE-conjugated primary antibody was used as a control. The efficiency of depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry and was essentially 100% efficient (Figure 6A). The CD45+ population was then obtained by washing the remaining cells from the depletion column. This population was approximately 25% CD45- (Figure 6A) and was added back to the CD45-depleted population. The CD45- cell population and the “add back CD45” population were cultured as before in osteogenic media for 10 days with or without the addition of IL-3. As shown in Figure 6B, CD45+ cell depletion from primary murine OBL cultures abrogated the inhibitory effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation. Adding back the CD45+ population reconstituted the inhibitory effects of IL-3. The effect of the known OBL inhibitor, TNF-α, was not changed by the depletion of murine CD45+ cells (Figure 6B). Similarly, CD45+ cell depletion of primary human BM cultures significantly decreased the inhibitory effect of IL-3 on CFU-F formation (Figure 6C).

Finally, flow cytometry was used to determine which hematopoietic subpopulations were represented in the CD45+ population. Markers used were CD3, CD11b, and CD19 for T cells, monocytes/macrophages, and B cells, respectively. Figure 7 shows that the CD45+ cells were CD3-/CD11b+/CD19- and belong to the monocyte/macrophage lineage.

We next examined if IL-3 inhibited osteoblastogenesis by inducing the secretion of a known OBL inhibitory factor such as TNF-α9 by CD45+ cells. ELISA analysis of conditioned media from murine stromal-cell cultures did not detect elevated levels of TNF-α at days 3, 6, and 9 of culture. TNF-α levels were 0 to 20 pg/mL at all time points. These TNF-α levels are lower than required to inhibit osteoblastogenesis in these cultures and were not changed by treatment with IL-3. In addition, neutralization of TNF-α in the cultures by the addition of an antimouse TNF-α antibody did not block the inhibitory effects of IL-3 (data not shown).

Discussion

MM bone disease results from both OCL bone destruction and decreased or absent OBL activity. Both histologic and isotopic scanning studies have demonstrated that OBL activity is decreased or absent at the sites of bone destruction and that bone formation is suppressed in MM patients.21 However, the basis for decreased OBL activity is unknown. In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that cytokines/chemokines produced by MM that increase OCL formation also decrease OBL differentiation. The major mediators of OCL activity in MM that are known include RANKL,3 MIP-1α,3 and IL-3.8 Others have demonstrated that RANKL does not inhibit OBL differentiation but in fact may increase OBL growth and differentiation.22 In preliminary studies, we found that MIP-1α or RANKL by itself did not block OBL differentiation (L.A.E., unpublished results, August 2003) even though stromal cells/osteoblasts express the CCR5 receptor for MIP-1α,23 and CD45+ cells present in the stromal-cell population express RANK.24 Therefore, we focused our studies on IL-3. Lee et al8 reported that 75% of patients with MM have increased IL-3 levels with a median value of 66.4 pg/mL compared with 22.1 pg/mL in healthy controls.

CD45+ cells in murine stromal-cell cultures are CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages by 2-color flow cytometry analysis. Mouse BM adherent cells were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 (A), anti-CD11b (B), or anti-CD19 (C). CD45+ cells were predominately CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages and negative for T- and B-cell markers (CD3 and CD19, respectively). Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant.

CD45+ cells in murine stromal-cell cultures are CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages by 2-color flow cytometry analysis. Mouse BM adherent cells were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 (A), anti-CD11b (B), or anti-CD19 (C). CD45+ cells were predominately CD11b+ monocytes/macrophages and negative for T- and B-cell markers (CD3 and CD19, respectively). Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each quadrant.

To determine the effects of IL-3 on OBL activity, we utilized both primary human and murine stromal-cell systems. Because the IL-3 protein is not homologous between human and murine systems, we used both to determine if the effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation were generalizable between species and if future studies in murine models of myeloma were feasible.

In our studies, OBL differentiation in both human and murine cultures was significantly inhibited in vitro by 100 pg/mL IL-3, comparable to the levels seen in patients with myeloma. Further, BM plasma from patients with MM with high IL-3 inhibited OBL differentiation in human CFU-F cultures. The inhibitory effects of plasma from patients with high IL-3 were partially reversed by the addition of a neutralizing antibody to human IL-3. In contrast, the inhibitory effects of marrow plasma from patients with normal IL-3 levels were unchanged by the addition of anti-IL-3.

Our results show that, unlike other inhibitors of OBL differentiation that act directly on OBL precursors, IL-3 acts indirectly via monocytes/macrophages. As shown in Figure 6A, CD45+/CD11b+ hematopoietic cells were present in these primary stromal-cell cultures. Importantly, depletion of the CD45+ cells in primary OBL cultures blocked the capacity of IL-3 to inhibit OBL differentiation. Importantly, reconstitution of the CD45- cultures with CD45+ cells restored the capacity of IL-3 to inhibit OBL differentiation. Consistent with IL-3 acting indirectly to block OBL differentiation, IL-3 did not inhibit differentiation of the preosteoblast cell lines, MC3T3-E1 or C2C12 (Figure 5A), even though they express IL-3Rα by RT-PCR (data not shown).

Other factors present in the MM marrow microenvironment also can enhance the inhibitory effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation. Low concentrations of TNF-α increased the inhibitory effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation (Figure 2F). TNF-α levels in myeloma have been reported to be increased, but there is no correlation between TNF-α levels and severity of bone disease in MM.25,26 Our results suggest that the low levels of TNF-α found in patients with myeloma that would normally not be sufficient to inhibit OBL differentiation may inhibit OBL differentiation when IL-3 is present. The effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation are not simply a result of increased TNF-α production by monocytes/macrophages responding to IL-3, because TNF-α levels were not increased in vitro by the addition of IL-3, and the inhibitory effects of IL-3 were not blocked by the addition of anti-TNF-α neutralizing antibodies (data not shown).

IL-3 by itself does not fully account for the inhibition in OBL differentiation in MM. As shown by our studies with marrow plasma from MM patients with high IL-3 levels, anti-IL-3 only partially reversed the inhibitory effects of IL-3 on OBL differentiation. Recently we have shown a potential role for IL-7 as an OBL inhibitor in MM.27 These data suggest that other OBL inhibitors, such as DKK1, sFRP-2 or -3, or IL-7, may act in conjunction with IL-3 to suppress OBL activity in MM.

Thus, in MM there appears to be at least 2 classes of OBL inhibitors: one that acts directly on osteoblasts such as DKK1 or sFRP-2 or -3 and one that appears to act indirectly, IL-3. IL-3 may act as a bifunctional mediator of MM bone disease, both increasing OCL formation and suppressing OBL differentiation. The identity of the factor(s) induced by IL-3 or its mechanism of action is as yet unknown. However, IL-3 does not affect Runx2 expression or DNA binding activity, suggesting that it may affect other signaling pathways involved in OBL differentiation. In preliminary experiments, IL-3 treatment, in contrast to DKK1, did not directly affect the wnt signaling pathway in stromal-cell cultures, suggesting that the IL-3-induced inhibitor has a different mechanism of action.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 5, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1080.

Supported by a Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal