Abstract

Activation of granulocyte effector functions, such as induction of the respiratory burst and migration, are regulated by a variety of relatively ill-defined signaling pathways. Recently, we identified a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase I-like kinase, CKLiK, which exhibits restricted mRNA expression to human granulocytes. Using a novel antibody generated against the C-terminus of CKLiK, CKLiK was detected in CD34+-derived neutrophils and eosinophils, as well as in mature peripheral blood granulocytes. Activation of human granulocytes by N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) and platelet-activating factor (PAF), but not the phorbol ester PMA (phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate), resulted in induction of CKLiK activity, in parallel with a rise of intracellular Ca2+ [Ca2+]i. To study the functionality of CKLiK in human granulocytes, a cell-permeable CKLiK peptide inhibitor (CKLiK297-321) was generated which was able to inhibit kinase activity in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of this peptide was studied on specific granulocyte effector functions such as phagocytosis, respiratory burst, migration, and adhesion. Phagocytosis of Aspergillus fumigatus particles was reduced in the presence of CKLiK297-321 and fMLP-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was potently inhibited by CKLiK297-321 in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, fMLP-induced neutrophil migration on albumin-coated surfaces was perturbed, as well as β2-integrin-mediated adhesion. These findings suggest a critical role for CKLiK in modulating chemoattractant-induced functional responses in human granulocytes.

Introduction

Human granulocytes, which include neutrophils and eosinophils, play an important role in host defense against invading pathogens.1 During induction of inflammatory reactions, granulocytes in the peripheral blood become primed or preactivated, leave the bloodstream by diapedesis through the endothelium, and migrate toward the site of inflammation.2 At the inflammatory site, granulocytes become highly activated, secrete proteolytic enzymes by degranulation, and form cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) to eliminate invading microorganisms.3 These granulocyte effector functions are initiated by inflammatory mediators, such as chemoattractants, which activate the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). One of the signaling events that occurs after ligand binding to GPCRs, is the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i). Ligand binding to GPCRs initially activates trimeric G-proteins and subsequent dissociation of the Gα and Gβγ subunits. The dissociation of the Gβγ subunit results in activation of phosphatidylinosytol-3-OH kinase (PI3K) and phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ). PLCβ activation in turn leads to the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol4,5phosphate (PIP2), producing diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-3 phosphate (IP3).4 Subsequently, IP3 binds to its receptor on the Ca2+ stores, resulting in Ca2+ release into the cytoplasm. Elevation of [Ca2+]i in granulocytes has been observed during activation of several granulocyte effector functions, for example in N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP)-induced respiratory burst.5,6 Additionally, Ca2+ has been implicated in the regulation of migration, since [Ca2+]i-buffered neutrophils demonstrated an abrogated integrin recycling and rear release.7,8 However, very few specific proteins have been identified that sense changes in [Ca2+]i and transduce these signals, modulating granulocyte functions.

We identified a novel protein kinase, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase I-like kinase (CKLiK), whose mRNA is specifically expressed in human granulocytes.9 CKLiK is highly homologous with CaMKI (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase I), a member of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) family.10 On the basis of the crystal structure of CaMKI, a general model for the activation of CaMKs has been proposed.11 Inactive CaMKs are in a “folded” configuration whereby the autoinhibitory domain acts as a pseudosubstrate by interacting with the N-terminal kinase domain. The calmodulin-binding domain is located on the C-terminus of CaMK. Ca2+-induced calmodulin binding results in “unfolding” and subsequent activation of CaMK.10 For CaMKII this activation has been correlated with autophosphorylation.12 CaMKIV has also been proposed to be autophosphorylated but not in the activation loop, which is the case for CaMKII.13 For CaMKI this remains to be proven. Full activity of CaMKI and CaMKIV is obtained by phosphorylation of a threonine residue by CaMK kinase (CaMKK) in their activation loop.14-16 CKLiK activity is also enhanced by coexpression of CaMKK, and CKLiK indeed has a threonine residue in the activation loop, suggesting regulation by CaMKK.9

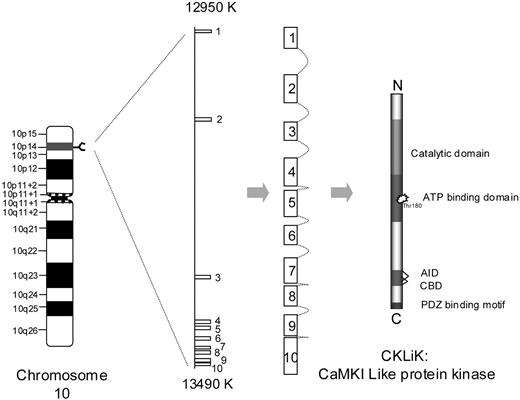

We have previously demonstrated that human neutrophils express abundant CKLiK mRNA but only low levels of CamKI and CamKII mRNA and with no expression of CamKIV.9,17 In this study we characterized the expression, regulation, and function of this novel Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase in human neutrophils and eosinophils. In silico we have identified the CKLiK gene as being located on chromosome 10 (10p14). CKLiK expression was detected in human eosinophils and neutrophils by using a novel antibody raised specifically against this kinase. Furthermore, we demonstrate that CKLiK can be activated specifically by physiologic relevant inflammatory mediators that induce elevations of [Ca2+]i. By the generation of a novel cell permeable inhibitory peptide for CKLiK, we were able to investigate a role of CKLiK in granulocyte effector functions. Addition of this peptide led to inhibition of phagocytosis and stimulus-induced respiratory burst activation. Additionally, an abrogated neutrophil migration and inhibition of β2-integrin activation by fMLP was observed in the presence of this peptide. These data suggest an important role for CKLiK in modulating granulocyte effector functions in response to stimulus-induced increases in [Ca2+]i.

Materials and methods

Cells, reagents, and antibodies

Murine myeloid 32D cells were cultured in RPMI 1640-glutamate supplemented with 8% Hyclone serum (Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) and mouse interleukin 3 (IL-3). Generation of 32D cells stably expressing pBabe-HA_CKLiK has been described previously.9 Stem cell factor and human FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (hFLT-3) ligand were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ), hIL-3 and human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (hG-CSF) were obtained from Strathmann (Hamburg, Germany), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was purchased from Endogen (Woburn, MA), hIL-5 was a kind gift of Dr I. Uings (GlaxoSmithKline, Stevenage, United Kingdom). fMLP was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Calmodulin was a kind gift of Dr R. de Groot (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands). Monoclonal antibodies, 12CA5 against hemagglutinin (HA) epitope were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals (Almere, The Netherlands). Cell permeable CKLiK297-321 was designed by linking it to the 11 amino acid sequence of the HIV tat protein (YGRKKRRQRRRIRKNFAKSKWRQAFNATAVVRHMRK). A scrambled tat-control peptide was used as a negative control (YGRKKRRQRRR-KVTRNAFWRKAKIHRVQMANFRSKA). Aspergillus fumigatus strain 46645 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The fusion protein of intracellular adhesion molecule-I (ICAM-I) crystallizable fragment (Fc), the constant region of an immunoglobulin, was a kind gift from Dr Y. van Kooyk (Free University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Generation of CKLiK antibody

Antibodies against the C-terminal part of CKLiK were generated by immunizing rabbits with an 11-amino-acid-synthesized peptide specific for CKLiK (CAYVAKPESLS), coupled to Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin. Antibody purification was performed by affinity chromatography. In short, the immunogenic peptide was coupled to an agarose carrier support using a SulfoLink kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Antibodies against the CKLiK peptide were allowed to bind to the peptide-coupled beads, washed with 100 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) pH 8 and eluted with glycine pH 3. Purified anti-CKLiK was dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.02% sodium azide and stored at 4°C.

Isolation of human neutrophils and eosinophils

Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers at the donor service of the University Medical Center (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Granulocytes were isolated from 0.4% (wt/vol) trisodium citrate (pH 7.4) treated blood as previously described.18 In short, mononuclear cells were depleted by centrifugation over isotonic Ficoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). After lysis of the erythrocytes in an isotonic ice-cold NH4Cl solution, granulocytes were washed and resuspended in incubation buffer (20 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 132 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.5% HAS [human serum albumin]. Eosinophils were separated from neutrophils by negative immunomagnetic selection with anti-CD16-conjugated microbeads (magnetic cell sorting [MACS]; Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Purity of eosinophils was more than 98%. Cord blood and peripheral blood samples were collected from healthy donors after informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocols were approved by the local ethics committee of the University Medical Center in Utrecht.

Isolation and culture of human CD34+ progenitor cells

CD34+ cells were isolated as previously described.19 In short, mononuclear cells were isolated from umbilical cord blood by density centrifugation over isotonic Ficoll solution (Pharmacia). Immunomagnetic selection with hapten-conjugated antibody against CD34 was used to isolate CD34+ cells (Miltenyi Biotech). CD34+ cells were cultured in Iscoves Modified Dulbecco Medium (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% FCS (fetal calf serum), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 U/mL penicillin, 10 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were differentiated toward neutrophils or eosinophils upon addition of SCF (50 ng/mL), FLT-3 (50 ng/mL), GM-CSF (0.1 nmol/l), IL-3 (0.1 nmol/l), and G-CSF (10 ng/mL) for neutrophils differentiation or IL-5 (0.1 nmol/L) for eosinophil differentiation. Every 3 or 4 days, cells were counted, and fresh medium was added to a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL. After 3 days of differentiation, only IL-3 and G-CSF or IL-5 was added to the cells as appropriate.

Analysis of CKLiK expression

CKLiK expression was analyzed by immune precipitation and Western blotting. For this, cells were stimulated as indicated and washed twice with cold PBS and lysed in a buffer containing, 1% NP-40 (Nonidet P-40, [Octylphenoxy]polyethoxyethanol), 20mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 10 mM MgCl2 supplemented with 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM diisopropyl-phosphorofluoride (DFP). Lysates were precleared for 20 minutes with protein-A Sepharose, and CKLiK was immune precipitated with anti-CKLiK for 1 to 2 hours. Immune precipitates were washed twice in cold PBS and denatured in sample buffer by boiling for 5 minutes. Samples were separated by a 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and analyzed by Western blotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% low-fat milk for 1 hour before hybridizing anti-CKLiK in 0.5% low-fat milk for 2 hours and swine anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated antibody (swarpo) or protein-A peroxidase-conjugated in 0.5% milk for 1 hour.

CKLiK kinase assay

CKLiK kinase assays were performed as previously described.9 In short, cells were stimulated as indicated, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer as described in “Analysis of CKLiK expression.” Lysates were precleared for 20 minutes with protein-A Sepharose beads and immune precipitated with CKLiK polyclonal antibody. Immune precipitates were washed twice in lysis buffer and twice in dilution buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4 and 20 mM MgCl2. Kinase assay was performed in the presence 10 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 50 μM ATP (adenosine triphosphate), 0.1 μL γ-32P-dATP (deoxyadenosine triphosphate) in the presence or absence of 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 μg calmodulin, 5 μg CREMβ (cAMP [cyclic adenosine monophosphate] responsive element modulator β) as substrate.20 After 20 minutes of incubation at room temperature, reactions were stopped by adding Laemli protein sample buffer and boiled for 3 minutes. Samples were separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed by autoradiography.

Detection of [Ca2+]i

Cells (4 × 106 cells) were loaded with 1.25 μM Fura-2AM (fura-2 [fluorescent Ca2+ indicator] acetoxymethyl ester; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 15 minutes, then washed and kept at room temperature. Cells were put in a quartz cuvette (400 μL, 2 × 106/mL) and stimulated with indicated chemoattractants. The fluorescence was measured under stirring conditions at 37°C in a Hitachi F-4500 fluorescent spectrophotometer (Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), using a multiwavelength time scan program. Fura-2 fluorescence was measured by excitation at 340 nm (F1) and 380 nm (F2), and an emission of 510 nm.

Phagocytosis of AfC-FITC by human granulocytes

Formaldehyde-fixed conidia of A fumigatus were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled and used as particles to be phagocytosed. The A fumigatus conidia (AfC) were harvested from a 14-day culture of A fumigatus strain (ATCC 46645) and fixed with 3% formaldehyde for at least 2 hours. FITC labeling of the formaldehyde fixed AfC occurred in 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer pH 9 with 1 mg/mL FITC.

AfC (106) were added to 5 × 105 granulocytes, in the absence or presence of CKLiK297-321 or tat-control peptide. The cell/AfC mixture was centrifuged at 25 g for 30 seconds and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C in the presence of 1% or 10% normal human pooled serum (NHS) to allow opsonization of AfC. After incubation the cell/AfC mixture was washed twice in an ice-cold PBS buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.02% sodium azide. To exclude the nonphagocytosed AfC, extracellular FITC was quenched by the addition of 1 mg/mL ethidium bromide, directly before fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. FACS analysis of phagocytosed AfC FITC was performed on FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Analysis of respiratory burst

Respiratory burst was measured by ROS-induced cytochrome c reduction.21 Assay was performed as previously described.22 In short, granulocytes (4 × 106 cells/mL) were preincubated with CKLiK297-321 or a tat-control peptide for 20 minutes and with GM-CSF (10-10 M) to prime the cells. Cytochrome c (75 μM) was added, and samples were transferred to a microtiter plate and placed in a thermostat-controlled plate reader (340 ATTC; SLT Lab Instruments, Salzburg, Austria). ROS production was induced by stimulation with 1 μM fMLP. Cytochrome c reduction was immediately measured every 12 seconds as an increase in absorbance at 550 nm.

Analysis of neutrophil migration

Migration experiments were performed as described previously.23 In short, glass coverslips were coated with a HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 132 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.5% human serum albumin). Purified neutrophils (106/mL HEPES buffer) were allowed to attach to the coverslip for 10 to 15 minutes at 37°C. Medium was removed, and the cells were washed 2 times with HEPES buffer. The coverslip was inverted in a droplet of medium containing 10-8 M fMLP and sealed with a mixture of beeswax, paraffin, and petroleum jelly (1:1:1, wt/wt/wt). Cell tracking at 37°C was monitored by time-lapse microscopy and analyzed by custom-made macro (A.L.I.) in the image analysis software Optimas 6.1 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Cell migration was followed for 10 minutes, making a picture every 20 seconds. Pictures were taken using a LeitX DXMRE microscope equipped with a PL flustar infinity B 20×/0.17 objective lens (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) and using a Sony XL-75CE CCD camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan).

Fluorescent bead adhesion assay

The fluorescent bead assay was performed as described by Geijtenbeek et al.24 Fluorescent beads (TransFluorSpheres, 488/645 nm, 1.0 μm; Molecular Probes) were coated with ICAM-1 Fc fusion protein. In short, 20 μL streptavidin (5 mg/mL in 50 mM MES (2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonate) buffer) was added to 50 μL TransFluorSpheres, mixed with 30 μL 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDAC; 1.33 mg/mL), and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 2 hours. The reaction was stopped by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 100 mM. Streptavidin-coated beads were washed 3 times with PBS and resuspended in 150 μL PBS, 0.5% BSA (wt/vol). Then, streptavidin-coated beads (15 μL) were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-human anti-Fc Fab2 fragments (6 μg/mL) in 0.3 mL PBS, 0.5% BSA for 2 hours at 37°C. The beads were washed once with PBS, 0.5% BSA and incubated with ICAM-1 Fc supernatant overnight at 4°C. The ligand-coated beads were washed; resuspended in 100 μL PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide; and stored at 4°C.

For the fluorescent bead adhesion assay, neutrophils were resuspended in 20 mM HEPES buffer supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 1.0 mM CaCl2, and 0.5% (wt/vol) HSA. Cells (5 × 104) were preincubated with control anti-HLA-ABC (W6/32) monoclonal antibody (MoAb; 10 μg/mL; ATCC hybridoma, Rockville, MD) or with anti-β2-integrin-blocking MoAb IB4 (10 μg/mL; ATCC hybridoma, Rockville, MD) and 50 μM tat proteins for 10 minutes at 37°C. The ligand-coated beads (40 beads/cell) and fMLP (10-7 M) were added in a 96-well V-shaped-bottom plate. Next, the preincubated neutrophils were added and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The cells were washed and resuspended in HEPES buffer (4°C) and kept on ice until analysis. Binding of the fluorescent beads to the neutrophils was determined by flow cytometry using the FACSvantage (Becton Dickinson). Binding is depicted as the percentage of neutrophils that bind to ICAM-1-coated beads.

Results

Chromosomal localization and expression of CKLiK

The draft sequence of the human genome has been completed,25 and we were able to determine the chromosomal localization and organization of the CKLiK gene. An in silico screen of the genomic sequence (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) identified the CKLiK gene as being located on chromosome 10, at position 10p14 as depicted in Figure 1.

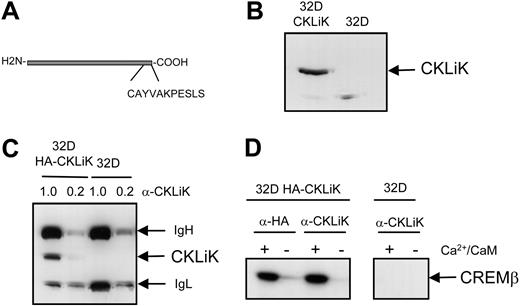

To study the expression of CKLiK in human granulocytes we generated a specific polyclonal antibody. An 11 amino acid peptide derived from the C-terminal part of CKLiK was used to immunize rabbits. This sequence was found to be specific for CKLiK and not for CaMKI or other CaMK family members (Figure 2A). Purification of the antibody was performed by affinity chromatography using the C-terminal CKLiK-peptide coupled to agarose beads. To test the antibody, we used 32D cells stably expressing epitope-tagged CKLiK (HA-CKLiK)9 and determined whether the antisera could be used for Western blotting (Figure 2B), immune precipitations (Figure 2C), and immune-complex kinase assays (Figure 2D). Both CKLiK in whole-cell lysates and immune-precipitated CKLiK could be detected but not in the control 32D cells lacking CKLiK (Figure 2B-C). Additionally, the functional kinase assays performed with the anti-CKLiK were comparable to the results obtained with an antibody against the HA epitope (Figure 2D). Thus, the antibody is specific for CKLiK and can be used for analysis of protein levels and kinase activity in primary granulocytes.

Chromosomal localization of CKLiK. The CKLiK gene is located on chromosome 10 at position 10p14. The gene overlaps a region of 530 000 base pair (bp) and consist of 10 exons, which form the CKLiK mRNA. CKLiK contains a catalytic domain, an ATP-binding domain, an auto inhibitory domain (AID), a calmodulin binding domain (CBD), and a hypothetical PDZ (PSD-95/SAP90, Drosophiliadiscs-large, and ZO-1)-binding motif.

Chromosomal localization of CKLiK. The CKLiK gene is located on chromosome 10 at position 10p14. The gene overlaps a region of 530 000 base pair (bp) and consist of 10 exons, which form the CKLiK mRNA. CKLiK contains a catalytic domain, an ATP-binding domain, an auto inhibitory domain (AID), a calmodulin binding domain (CBD), and a hypothetical PDZ (PSD-95/SAP90, Drosophiliadiscs-large, and ZO-1)-binding motif.

Characterization of CKLiK antibody. (A) An antibody against the C-terminal portion of CKLiK was generated by immunizing rabbits with a Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH)-coupled peptide as indicated. (B) Western blots with CKLiK antisera were performed. 32D cells (106) stably expressing an N-terminal epitope-tagged CKLiK (32D HA-CKLiK) or control cells (32D) were lysed and separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Immune precipitations were performed with CKLiK antibody. 32D cells (107) were lysed, and immune precipitations were performed with 1 μL and 0.2 μL purified CKLiK antibody (α-CKLiK) as indicated. CKLiK, as well as the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) and immunoglobulin light chain (IgL), are indicated. (D) Immune-complex kinase assays were performed with or without Ca2+ and calmodulin, using the CKLiK antibody and an antibody against the epitope-tag (α-HA) as a control. CREMβ was used as a substrate.

Characterization of CKLiK antibody. (A) An antibody against the C-terminal portion of CKLiK was generated by immunizing rabbits with a Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH)-coupled peptide as indicated. (B) Western blots with CKLiK antisera were performed. 32D cells (106) stably expressing an N-terminal epitope-tagged CKLiK (32D HA-CKLiK) or control cells (32D) were lysed and separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting was performed as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Immune precipitations were performed with CKLiK antibody. 32D cells (107) were lysed, and immune precipitations were performed with 1 μL and 0.2 μL purified CKLiK antibody (α-CKLiK) as indicated. CKLiK, as well as the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) and immunoglobulin light chain (IgL), are indicated. (D) Immune-complex kinase assays were performed with or without Ca2+ and calmodulin, using the CKLiK antibody and an antibody against the epitope-tag (α-HA) as a control. CREMβ was used as a substrate.

CKLiK activity in human granulocytes is dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin

We previously demonstrated high mRNA expression of CKLiK in human granulocytes and in neutrophils derived from CD34+ cells.9 Here, we analyzed CKLiK protein expression in neutrophils and eosinophils derived by the differentiation of hematopoietic CD34+ stem cells cultured with G-CSF or IL-5, respectively, and isolated peripheral blood granulocytes. CKLiK was found to be present in both ex vivo-differentiated neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 3A, left), with a higher expression in eosinophils than in neutrophils. In peripheral blood neutrophils a low expression of CKLiK was observed, compared with the expression in eosinophils (Figure 3A, right). To demonstrate whether immune-precipitated CKLiK indeed requires Ca2+ and calmodulin for kinase activity, we differentiated CD34+ progenitor cells to neutrophils and eosinophils and performed immune precipitation using CKLiK antibody. CKLiK kinase assays were performed using CREMβ as a substrate. Indeed, only in the presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin CKLiK kinase activity could be observed (Figure 3B, top). Using peripheral blood eosinophils and neutrophils we also observed elevated CKLiK kinase activity in the presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin (Figure 3B, bottom). A low basal kinase activity was observed in the absence of Ca2+/calmodulin in peripheral neutrophils. It is possible that neutrophils display a constitutively low CKLiK kinase activity; however, we cannot exclude that CKLiK becomes modestly activated during cell isolation.

Inflammatory mediators activate CKLiK in human granulocytes

Granulocytes can be activated by a variety of inflammatory mediators. Since CKLiK is activated by Ca2+ and calmodulin we investigated the induction of CKLiK activity by physiologically relevant agents that induce a rise in [Ca2+]i. We stimulated purified peripheral blood neutrophils with fMLP and eosinophils with platelet-activating factor (PAF) for the times indicated. Subsequently, cells were lysed, and CKLiK kinase assays were performed. Phosphorylation of CREMβ observed in eosinophils reached a maximum of CKLiK activity after 1 minute (Figure 4A), while in neutrophils already after 30 seconds of stimulation with fMLP a maximum was reached (Figure 4B). Incubation with PMA, a potent artificial activator of several neutrophil functions, but not specifically for Ca2+-mediated processes, did not result in activation of CKLiK (Figure 4C). The activity of CKLiK, detected after PAF and fMLP stimulation in eosinophils versus neutrophils, decreased after 2 minutes. This transient activation of CKLiK follows the rise of intracellular Ca2+ normally observed after activation of G-protein-coupled receptors in these cells as demonstrated in Figure 4D.

CKLiK297-321 reduces ROS production and phagocytosis by human granulocytes

While we have demonstrated expression and regulation of CKLiK in human granulocytes, a role for this kinase in regulating granulocyte effector functions remains unclear. To investigate this question we generated an inhibitory, cell permeable CKLiK peptide, (297IRKNFAKSKWRQAFNATAVVRHMRK321) based on previous findings.26 To study the functional role of CKLiK in human granulocytes we linked this peptide to the 11-amino acid portion of the HIV tat protein, generating a peptide capable of transducing primary cells.23,27,28 We first investigated the ability of this peptide, CKLiK297-321, to inhibit the kinase activity of CKLiK. Indeed we could demonstrate a dose-dependent inhibitory effect of CKLiK297-321 on the ability of CKLiK to phosphorylate the substrate CREMβ (Figure 5A). This we also observed using the active truncated form of CKLiK, which lacks the calmodulin binding domain (Figure 5B). No inhibition of kinase activity was observed using a scrambled control peptide. We further investigated the effect of CKLiK297-321 on the production of ROS in human granulocytes, since a role for Ca2+ in the respiratory burst has been proposed.29 For optimal activation of the respiratory burst cells need to be preactivated or “primed.”30 Therefore, cells were first treated with GM-CSF or PAF, and initiation of the respiratory burst was induced by fMLP. ROS production was dramatically inhibited by the CKLiK297-321 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6A), while no inhibition was observed with 50 μM tat-control peptide.

Expression and activation of CKLiK in human eosinophils and neutrophils. (A) CKLiK was immune-precipitated with CKLiK antibody from stem cells differentiated toward neutrophils (neutro; 2.5 × 107 and 1.5 × 107 as indicated) and eosinophils (eo; 1.5 × 107) (left) and from peripheral blood neutrophils (2 × 107) and eosinophils (107) (right, with a longer exposure below) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed with the CKLiK antibody. Heavy and light chains of CKLiK antibody and immune-precipitated CKLiK are indicated. (B) Kinase activity of CKLiK is dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM). Kinase assays were performed in the absence or presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin with CKLiK immune-precipitated from stem cells differentiated toward neutrophils and eosinophils (top) and with CKLiK obtained from peripheral blood eosinophils and neutrophils (bottom). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Expression and activation of CKLiK in human eosinophils and neutrophils. (A) CKLiK was immune-precipitated with CKLiK antibody from stem cells differentiated toward neutrophils (neutro; 2.5 × 107 and 1.5 × 107 as indicated) and eosinophils (eo; 1.5 × 107) (left) and from peripheral blood neutrophils (2 × 107) and eosinophils (107) (right, with a longer exposure below) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed with the CKLiK antibody. Heavy and light chains of CKLiK antibody and immune-precipitated CKLiK are indicated. (B) Kinase activity of CKLiK is dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM). Kinase assays were performed in the absence or presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin with CKLiK immune-precipitated from stem cells differentiated toward neutrophils and eosinophils (top) and with CKLiK obtained from peripheral blood eosinophils and neutrophils (bottom). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

CKLiK activity induced by inflammatory mediators. Peripheral blood eosinophils (A) and neutrophils (B-C) were isolated and stimulated with PAF (10-6 M), fMLP (10-6 M), or PMA (100 ng/mL), respectively. Cells were lysed (3 × 107 cells/point) and immunoprecipitated with CKLiK antibody, and kinase assays were performed without addition of Ca2+ and calmodulin, except for positive controls. (D) Ca2+ response of neutrophils to fMLP. Cells were loaded with Fura-2AM for 15 minutes and washed. Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured at 340 nm (F1) and 380 nm (F2) at 510 emission using a Hitachi F4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Similar Ca2+ responses were obtained after PAF stimulation of eosinophils (data not shown).

CKLiK activity induced by inflammatory mediators. Peripheral blood eosinophils (A) and neutrophils (B-C) were isolated and stimulated with PAF (10-6 M), fMLP (10-6 M), or PMA (100 ng/mL), respectively. Cells were lysed (3 × 107 cells/point) and immunoprecipitated with CKLiK antibody, and kinase assays were performed without addition of Ca2+ and calmodulin, except for positive controls. (D) Ca2+ response of neutrophils to fMLP. Cells were loaded with Fura-2AM for 15 minutes and washed. Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured at 340 nm (F1) and 380 nm (F2) at 510 emission using a Hitachi F4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Similar Ca2+ responses were obtained after PAF stimulation of eosinophils (data not shown).

In addition, the involvement of elevated [Ca2+]i in phagocytosis has been demonstrated.31,32 Therefore, the effect of CKLiK297-321 on phagocytosis, a process preceding activation of the respiratory burst, was studied (Figure 6B). For this we used phagocytosis of A fumigatus conidia by human neutrophils as a physiologically relevant model. NHS was used to opsonize the AfC particles and to allow complement receptor type 3 (CR3) and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis by granulocytes. A maximum percentage of phagocytic cells of 36.4% plus or minus 4.5% in the presence of 1% NHS was reached, and 69.7% plus or minus 0.5% in the presence of 10% NHS. Treatment of 50 μM CKLiK(296-321) demonstrated a significant reduction of granulocytes positive for phagocytosed AfC-FITC particles to 21.8% plus or minus 1.7%, and 54.0% plus or minus 6.9% in the presence of 1% or 10% NHS, respectively. This indicates a partial, but significant, role for CKLiK in regulating phagocytosis together with a role for CKLiK in the regulation of the respiratory burst in human granulocytes.

CKLiK297-321 inhibits CKLiK kinase activity. A cell permeable CKLiK peptide YGRKKRRQRRRIRKNFAKSKWRQAFNATAVVRHMRK was synthesized. (A) 32D cells stably expressing HA-CKLiK were lysed, and CKLiK was immunoprecipitated. CKLiK kinase assays were performed with increasing concentrations of CKLiK297-321 as indicated. CREMβ was used as a substrate. A scrambled tat-control peptide was used a negative control. (B) COS cells were transiently transfected with 100 ng HA-CKLiK-296 or HA-CKLiK-WT (wild type). CKLiK was immune-precipitated with an antibody against the HA-epitope tag, and kinase assays were performed in the absence of Ca2+/calmodulin. Kinase assays with HA-CKLiK-WT were performed in the presence or absence of Ca2+/calmodulin, as positive and negative control, respectively.

CKLiK297-321 inhibits CKLiK kinase activity. A cell permeable CKLiK peptide YGRKKRRQRRRIRKNFAKSKWRQAFNATAVVRHMRK was synthesized. (A) 32D cells stably expressing HA-CKLiK were lysed, and CKLiK was immunoprecipitated. CKLiK kinase assays were performed with increasing concentrations of CKLiK297-321 as indicated. CREMβ was used as a substrate. A scrambled tat-control peptide was used a negative control. (B) COS cells were transiently transfected with 100 ng HA-CKLiK-296 or HA-CKLiK-WT (wild type). CKLiK was immune-precipitated with an antibody against the HA-epitope tag, and kinase assays were performed in the absence of Ca2+/calmodulin. Kinase assays with HA-CKLiK-WT were performed in the presence or absence of Ca2+/calmodulin, as positive and negative control, respectively.

CKLiK297-321 inhibits migration of human granulocytes

Although a specific mechanism by which changes in [Ca2+]i regulate migration has not been defined, some aspects of the migration process have been shown to be at least partially controlled by changes in [Ca2+]i.8,33 We analyzed the effect of CKLiK297-321 on granulocyte migration on albumin-coated coverslips. Migration of fMLP-stimulated neutrophils was measured by time-lapse imaging during 10 minutes. The effect of CKLiK297-321 and tat-control peptides on the fMLP-induced migration was investigated (Figure 7A, top). Migration distance is visualized by showing the tracks of 40 cells (top panels) and the centered tracks (bottom). Upon fMLP stimulation, neutrophil migration was markedly increased compared with the untreated cells, which showed little or no movement (data not shown). fMLP-treated cells migrated with a speed of 6.7 plus or minus 0.5 μm/min (Figure 7B). Preincubation with CKLiK297-321 strongly inhibited fMLP-induced migration, as demonstrated by a reduction of the speed to 1.5 plus or minus 0.4 μm/min. From the tracks in the lower panel of Figure 7A, it can be concluded that most cells incubated with CKLiK297-321 demonstrated a completely abrogated migration. Treatment with the tat-control peptide showed no significant inhibition.

Effect of CKLiK297-321 peptide on respiratory burst and phagocytosis. (A) Granulocytes were isolated and treated with GM-CSF (10-10 M) to prime the cells. Cells were then treated without (-) or with increasing concentrations of CKLiK297-321 or a scrambled tat-control peptide for 20 minutes. Respiratory burst was initiated with fMLP (10-6 M). ROS production was measured by cytochrome c reduction, resulting in a change of optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 550 nm. An average of 3 independent experiments is depicted. (B) Granulocytes and FITC-labeled AfC (ratio 1:2) together with no, 1%, or 10% NHS were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C to allow phagocytosis in the presence or absence of 50 mM CKLiK297-321 or tat-control peptide. The percentage of AfC-phagocytosed neutrophils was detected by FACS analysis. Mean percentage of FITC-positive neutrophils ± SEM of 3 independent experiments is depicted. Student t test demonstrated a significant inhibition with P < .05.

Effect of CKLiK297-321 peptide on respiratory burst and phagocytosis. (A) Granulocytes were isolated and treated with GM-CSF (10-10 M) to prime the cells. Cells were then treated without (-) or with increasing concentrations of CKLiK297-321 or a scrambled tat-control peptide for 20 minutes. Respiratory burst was initiated with fMLP (10-6 M). ROS production was measured by cytochrome c reduction, resulting in a change of optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 550 nm. An average of 3 independent experiments is depicted. (B) Granulocytes and FITC-labeled AfC (ratio 1:2) together with no, 1%, or 10% NHS were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C to allow phagocytosis in the presence or absence of 50 mM CKLiK297-321 or tat-control peptide. The percentage of AfC-phagocytosed neutrophils was detected by FACS analysis. Mean percentage of FITC-positive neutrophils ± SEM of 3 independent experiments is depicted. Student t test demonstrated a significant inhibition with P < .05.

CKLiK297-321 abrogates fMLP-induced migration and inhibits fMLP-induced β2-integrin activation. (A) Migration of granulocytes was monitored by time-lapse analysis. Cells were first allowed to attach on albumin-coated coverslips for 15 minutes. Granulocytes were incubated as indicated with 50 μM CKLiK297-321 or 50 μM scrambled tat control peptide. Neutrophil migration was induced by fMLP (10-8 M) and imaged every 20 seconds for 10 minutes. Migration tracks of individual cells are shown per cell (top row) and centered (bottom row). (B) Average migration speed of at least 3 independent experiments are calculated and expressed as micrometers per minute ± SEM. (C) Granulocytes were preincubated with CKLiK297-321 or with scrambled tat control peptide in the presence of control antibody (W6/32) or blocking antibody against β2-integrins (IB4) as indicated. Preincubated granulocytes were added to wells containing buffer or fMLP (10-8 M) and ICAM-1-coated beads. After 15 minutes at 37°C the cells were washed, and the percentage of cells that were positive for beads was determined by flow cytometry. Depicted is the average of 3 experiments with SEM.

CKLiK297-321 abrogates fMLP-induced migration and inhibits fMLP-induced β2-integrin activation. (A) Migration of granulocytes was monitored by time-lapse analysis. Cells were first allowed to attach on albumin-coated coverslips for 15 minutes. Granulocytes were incubated as indicated with 50 μM CKLiK297-321 or 50 μM scrambled tat control peptide. Neutrophil migration was induced by fMLP (10-8 M) and imaged every 20 seconds for 10 minutes. Migration tracks of individual cells are shown per cell (top row) and centered (bottom row). (B) Average migration speed of at least 3 independent experiments are calculated and expressed as micrometers per minute ± SEM. (C) Granulocytes were preincubated with CKLiK297-321 or with scrambled tat control peptide in the presence of control antibody (W6/32) or blocking antibody against β2-integrins (IB4) as indicated. Preincubated granulocytes were added to wells containing buffer or fMLP (10-8 M) and ICAM-1-coated beads. After 15 minutes at 37°C the cells were washed, and the percentage of cells that were positive for beads was determined by flow cytometry. Depicted is the average of 3 experiments with SEM.

Important receptors for migration of neutrophils are the β2-integrins; therefore, we addressed the role of β2-integrins in ICAM-1 binding using a fluorescent bead adhesion assay. Neutrophils were treated with or without CKLiK297-321 or tat-control peptides, and ICAM-1 binding was analyzed (Figure 7C). The presence of CKLiK297-321 had little effect on ICAM-1 binding in the absence of stimulation. However, when neutrophils were stimulated with fMLP, there was a significant increase in the percentage of ICAM-1-binding cells. Importantly, this was abrogated by addition of CKLiK297-321 but not the control tat-peptide. Adhesion of neutrophils to the ICAM-1 Fc-coated beads was inhibited by blocking β2-integrins (MoAb IB4), demonstrating that ICAM-1 binding was indeed a β2-integrin-dependent process. These data suggest that the inhibition of migration observed by incubating neutrophils with CKLiK297-321 is due to an inhibition of β2-integrin activation.

Discussion

In this report we analyzed the protein expression, regulation, and function of the recently identified protein kinase CKLiK in primary human granulocytes. Comparison of expression levels between peripheral blood neutrophils and eosinophils shows higher CKLiK protein levels in human eosinophils. However, neutrophils derived by differentiation of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors also demonstrate a high CKLiK expression (Figure 3A). Low expression of CKLiK in neutrophils might be due to proteolytic breakdown hampering detection, since these cells contain greater protease activity than peripheral blood eosinophils.34 Immune complex kinase assays of CKLiK in human granulocytes, confirm the Ca2+ and calmodulin dependency expected of this protein kinase (Figure 3B). Furthermore, a higher basal level of CKLiK activity in human neutrophils compared with eosinophils was observed, which could indicate that CKLiK is already activated in unstimulated neutrophils, or that there is a low stimulus-independent activity of CKLiK in human neutrophils. Alternatively, isolation of neutrophils might induce some artificial cellular activation.35 For CaMKII and CaMKV a Ca2+-independent activity has been demonstrated.36 For the closely related CaMKIV it has been suggested that phosphorylation of Thr196 by CaMKK resulted in a Ca2+-independent activity.16 However, for CaMKI this could not be demonstrated.10 Our previous findings with cotransfection studies of CKLiK and CaMKK indeed demonstrated a small Ca2+-independent activity.9 PAF and fMLP are both inflammatory mediators that can trigger a rise in [Ca2+]i, by binding to their respective G-protein-coupled receptors. PAF in eosinophils and fMLP in neutrophils are potent inducers of granulocyte effector functions. Here, we demonstrate that stimulation of granulocytes with these inflammatory mediators results in induction of CKLiK kinase activity (Figure 4). This activation of CKLiK parallels the transient rise of Ca2+ observed upon fMLP stimulation and is in line with the observed Ca2+-dependent CKLiK activation. PMA, a pharmacologic activator protein kinase C (PKC), is also a potent activator of granulocyte function but was unable to induce CKLiK activation (Figure 4C).

Terminally differentiated cells such as granulocytes are difficult to manipulate by conventional transfection methodologies. Thus far, most studies that describe the role of intracellular signaling pathways in granulocyte functioning have been performed using pharmacologic inhibitors. We have demonstrated that eosinophils could be transduced with dominant-negative or constitutively active variants of Ras and Rho, linked to an 11-amino-acid sequence (YGRKKRRQRRR) from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Tat protein.23,28 This sequence has been found to be one of the most efficient domains at allowing proteins to traverse cell membranes, probably in a receptor-independent fashion.37-39 When expressed as a N-terminal peptide linked to an unrelated protein, this sequence renders the fusion protein capable of entering cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner into multiple cell types.25,40,41 To investigate a role for CKLiK, we generated an inhibitory peptide containing amino acids 297 to 321 of CKLiK linked to the tat protein transduction domain. A similar, but distinct, sequence derived from CaMKI and CaMKII has previously been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the kinase activity of CaMKI and CaMKII, respectively.26,42 We were able to demonstrate a potent inhibitory effect of the CKLiK peptide on CKLiK kinase activity (Figure 5A). On the basis of the crystal structure of CaMKI and mutation analysis it has been suggested that, in an inactive state, the autoinhibitory domain of CKLiK acts as a pseudosubstrate by binding to the catalytic domain.11 Indeed, the autoinhibitory domain of CKLiK is located in the sequence of the peptide, suggesting a mechanism by which this peptide can block the catalytic domain of CKLiK. Additionally, the autoinhibitory domain and the calmodulin-binding domain are in critically close proximity and probably are overlapping,26 which indicates that this peptide may also act as a competitor of CKLiK for calmodulin binding. To demonstrate that CKLiK297-321 specifically inhibits the kinase domain of CKLiK, we investigated the ability of this peptide to inhibit the active form of CKLiK (CKLiK-296), which lacks the calmodulin binding domain. We indeed demonstrated that the CKLiK peptide could inhibit the kinase activity of this truncated form of CKLiK, suggesting that the CKLiK297-321 inhibits specifically the kinase domain of CKLiK (Figure 5B).

Phagocytosis and production of reactive oxygen species by the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase are critical granulocyte effector function required for the elimination of invading pathogens. Phagocytosis is a multicomponent-mediated process which involves Fc receptors and complement receptor 3 (Mac-1) present on the surface of human neutrophils. A role for Ca2+ in Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis has been previously demonstrated.31 Recently, by studying single-cell phagocytosis, Dewitt et al32 demonstrated increased [Ca2+]i at the stage of phagocytotic cup formation and a correlation between the onset of oxidative activity and a second elevation of [Ca2+]i. In our study we observe a partial, but significant, reduction of phagocytotic neutrophils containing FITC-labeled A fumigatus conidia, when granulocytes were treated with CKLiK297-321 (Figure 6C). This partial inhibition of CKLiK297-321 can be explained by the complexity of our model. In this model both CR3 and Fc receptors are activated. A Ca2+ independency of CR3-mediated phagocytosis has been proposed,31 and in addition Ca2+-independent Fc γ receptor I (FcγRI)-mediated phagocytosis has been described.43 This suggests that a role for CKLiK is perhaps restricted to the FcγRIIa-, FcγRIIIb-, and FcαRI-mediated phagocytosis. The importance of the NADPH oxidase is demonstrated in patients with chronic granulomatous disease, which is caused by a defect in one of the components of the NADPH oxidase.44 In resting cells, the subunits of NADPH oxidase are localized at the membrane of specific granules (gp91phox and p22phox) and in the cytoplasm (p47phox and p67phox and p40phox).3,41,45 In response to stimulation with inflammatory mediators, such as fMLP, the cytosolic subunits and the small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) p21Rac and p21Rap are activated and interact with the membrane-bound subunits to form an activated enzyme complex. It has been described that formation of ROS in human granulocytes requires intracellular Ca2+.6,29,32 However, the mechanism by which Ca2+ is linked to the regulation of the respiratory burst is still unclear. Here we demonstrate that incubation of granulocytes with CKLiK297-321 resulted in reduced ROS production when stimulated with fMLP but not PMA (Figure 6; data not shown). One of the possible mechanisms by which CKLiK can influence the respiratory burst is via the activation of the small GTPases Rac or Rap1.46,47 Both Rac and Rap1 have been shown to be activated by stimulation with the calcium ionophore ionomycin, or thapsigargin, which both elevate [Ca2+]i,7 although in Ca2+-depleted cells, GTP loading of Rac and Rap1 could still be observed.48,49 For Rap1 it has been described that it can be phosphorylated directly by CaMKIV in vitro, suggesting a link between Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent signaling mechanism and small GTPase signaling.50 Therefore, it might be possible that CKLiK exerts a similar effect toward Rap1 in human granulocytes. Also, several findings support the involvement of Ca2+ in the activation of Rac. For example, in guinea pig neutrophils Rac GTP-loading could be inhibited by calmodulin inhibitors.51 Furthermore, there are some indications that several guanine exchange factors (GEFs), which activate small GTPases by the exchange of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to GTP, can be activated in a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. For Rac, 2 exchange factors have been identified: Vav and Tiam.52,53 Vav is predominantly expressed in hematopoietic cells and is activated by tyrosine phosphorylation, which excludes a direct role for CKLiK. Tiam1, however, has been shown to be phosphorylated by CaMKII, which results in translocation of Tiam1 to the membrane.54,55 It is still not clear which exchange factor is involved in the activation of Rac2 or Rap1 in the NADPH complex in human granulocytes, and there are contradictory findings about the Ca2+-dependent activation of Rac. However, it is still a possibility that CKLiK regulates the activity or the translocation of a GEF involved in small GTPase activation. Another potential role for CKLiK in regulating the respiratory burst involves the phosphorylation of p47phox. Membrane translocation in intact cells is dependent on phosphorylation of multiple serine residues of p47phox..56 p47phox Phosphorylation occurs on multiple serine residues after neutrophil stimulation with fMLP.42,57 These include some potential CKLiK phosphorylation sites for p47phox, as was identified by consensus site comparison (data not shown).

Neutrophils treated with an inhibitor of CKLiK showed a perturbed migration on albumin-coated surfaces (Figure 7A-B). Inhibited movement of neutrophils on a variety of substrates has been shown to be associated with clustering of integrins at the rear of the cell and/or impaired uropod retraction.7,8 This force-mediated retraction in neutrophils was found to be dependent on the phosphorylation of myosin II. Phosphorylation of the myosin light chain can be mediated by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase or the Rho kinase pathway, which acts downstream of Rho.8,23 Both processes are described in granulocytes and could possibly involve CKLiK. Additionally, in motile neutrophils, a Ca2+-dependent endocytotic recycling of integrins back to the leading edge of the migrating cell has been suggested. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that inhibition of CaMKII resulted in induction of a high-affinity state of β1-integrins,58 suggesting a role for CaMKII in β1-detachment. A similar role for CKLiK might be possible; however we observed a reduced adhesion of neutrophils to ICAM-1 in the presence of the CKLiK inhibitor, which rather favors a role for CKLiK in the activation of β2-integrins (Figure 7C). However, detailed analysis is required to unravel the mechanism on how CKLiK activity leads to the activation of β2-integrins in human granulocytes. Preliminary results show that CKLiK does not work on the level of modulating the high activation status of Mac-1 as determined by the binding of the MoAb CBRM1/5 (L.U., unpublished observations, November 2004).

Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that CKLiK is a Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase that couples G-protein-coupled receptor stimulation to granulocyte functionality. This is together with the restricted expression that the kinase might make it an interesting drug target for manipulating granulocyte function in a variety of inflammatory conditions.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 19, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3755.

Supported by a grant of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO; 016.036.051) (L.U.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr T. Geijtenbeek for helpful discussions in setting up the fluorescent bead assay and Claudia van der Velden for technical assistance.

![Figure 4. CKLiK activity induced by inflammatory mediators. Peripheral blood eosinophils (A) and neutrophils (B-C) were isolated and stimulated with PAF (10-6 M), fMLP (10-6 M), or PMA (100 ng/mL), respectively. Cells were lysed (3 × 107 cells/point) and immunoprecipitated with CKLiK antibody, and kinase assays were performed without addition of Ca2+ and calmodulin, except for positive controls. (D) Ca2+ response of neutrophils to fMLP. Cells were loaded with Fura-2AM for 15 minutes and washed. Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured at 340 nm (F1) and 380 nm (F2) at 510 emission using a Hitachi F4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Similar Ca2+ responses were obtained after PAF stimulation of eosinophils (data not shown).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/106/3/10.1182_blood-2004-09-3755/6/m_zh80150581690004.jpeg?Expires=1767709355&Signature=VH3I6V6zgUSrXfM-DvojO9kYqtsqBP~SvGLXzGNs9489WQD93qs6bXJNGzq~RMU~zHqmK~YlG6Q6P9yHQhgBjufhpc9ImzQrG87xUGLy84~6A2aQWmqOoL4SOYUMgT4NKWovIxX1m6eI449NixSnuRLZ-qJEAqUbbah-0NL7Q7tm3V6YYtDRZXZFe~kYIF~Myr~HOojNzKGO5OVBoRyZiHQ24ew9I1c~WOXwYF7~aJx7SBZwP2wWCqfQV7DH~XP1heuif1CsPAHQPI1d6TCTBGgtptJvcfkhsWH936CBGZAobzLpZuO254D55TFCKU-wpxdhQP2fGNpqAQT~WlwJlw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal