Abstract

In clinical bone marrow transplantation, the severe cytopenias induced by bone marrow ablation translate into high risks of developing fatal infections and bleedings, until transplanted hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells have replaced sufficient myeloerythroid offspring. Although adult long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) are absolutely required and at the single-cell level sufficient for sustained reconstitution of all blood cell lineages, they have been suggested to be less efficient at rapidly reconstituting the hematopoietic system and rescuing myeloablated recipients. Such a function has been proposed to rather be mediated by less well-defined short-term hematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSCs). Herein, we demonstrate that Lin–Sca1+kithiCD34+ short-term reconstituting cells contain 2 phenotypically and functionally distinct subpopulations: Lin–Sca1+kithiCD34+flt3– cells fulfilling all criteria of ST-HSCs, capable of rapidly reconstituting myelopoiesis, rescuing myeloablated mice, and generating Lin–Sca1+kithiCD34+flt3+ cells, responsible primarily for rapid lymphoid reconstitution. Representing the first commitment steps from Lin–Sca1+kithi CD34–flt3– LT-HSCs, their identification will greatly facilitate delineation of regulatory pathways controlling HSC fate decisions and identification of human ST-HSCs responsible for rapid reconstitution following HSC transplantations.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are defined by their unique capacity to self-renew as well as to multilineage differentiate into all blood cell lineages and are therefore crucial for reconstitution of hematopoiesis on transplantation into recipients with bone marrow (BM) ablation.1,2 Although representing only approximately 0.05% to 0.1% of total murine BM cells, virtually all HSC activity has been shown to be contained within the lineage–/lo (Lin–/lo) Sca1+ kithi (LSK) HSC compartment.3-5 However, the LSK HSC compartment is heterogeneous and the prevailing model of hematopoiesis suggests that the HSC pool consists of at least 2 functionally distinct HSC subpopulations, long-term and short-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs, respectively). LT-HSCs have extensive (life-long) self-renewing potential and on commitment give rise to ST-HSCs with more restricted self-renewing capacity.2,6 As a consequence, following transplantation procedures in lethally myeloablated recipients, LT-HSCs are both required and sufficient to secure life-long reconstitution of the entire hematopoietic system. However, because LT-HSCs can reconstitute hematopoiesis long-term at very low numbers (one cell in mice),7,8 the lack of sufficient LT-HSCs is unlikely to represent a significant problem in clinical BM transplantation. Rather, rapid and efficient replacement of short-lived myeloerythroid cell lineages is critical to overcome life-threatening cytopenia following severe insults to the hematopoietic system, as well as in the first weeks after transplantation.9 Multiple studies have suggested that LT-HSCs, in addition to being extremely rare, might also not be the most efficient cells at rapidly reconstituting the hematopoietic system and thereby protecting lethally irradiated (myeloablated) mice, probably reflecting their quiescent nature and their delayed production of mature progeny,7,10-12 although higher doses of LT-HSCs might also be able to rapidly reconstitute ablated recipients.13 In contrast, committed myeloerythroid progenitors are radioprotective, but only if transplanted at very high numbers,9 suggesting that a more primitive ST-HSC population with some, albeit limited, self-renewing potential might be responsible for the short-term and rapid replenishment of myeloerythroid progenitors and thereby for rescuing mice from lethal myeloablation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the LSK HSC pool can be further subdivided using additional markers, of which Thy-1.1 and CD34 have proved particularly useful, because LT-HSCs in adult murine BM are LSKThy-1.1lo and LSKCD34–.3,7,14,15 Recently, LSK cells lacking expression of the cytokine polypeptide deformylase (fms)–like tyrosine kinase receptor 3 (flt3) were shown to completely overlap with the LSKThy-1.1lo phenotype, and therefore to contain all LT-HSCs.16,17 However, in contrast to LT-HSCs, the identity and potential heterogeneity of ST-HSCs remains unclear. Short-term stem and progenitor cell activities have been suggested to reside within the LSKCD34+ as well as LSKflt3+ BM compartments.7,16,17 However, LSKflt3+ cells, although having a prominent short-term reconstitution potential, appear to be predominantly directed toward replenishment of lymphoid rather than myeloid lineages16 and LSKCD34+ cells are likely to be highly heterogeneous.7 In the present studies we demonstrate that the LSK HSC compartment, in addition to LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs, contains LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+, functionally distinct subsets of ST-HSCs, redefining the HSC hierarchy in mice.

Materials and methods

Subfractionation and purification of LSK cells based on expression of CD34 and flt3

Animal procedures were performed with consent from the local ethics committee at Lund University (Lund, Sweden). Lineage-depleted (Lin–) BM cells from 11- to 14-week-old C57Bl/6 (CD45.2) mice were enriched with immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as described.16 Remaining Lin+ cells were visualized with goat antirat-Tricolor (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and incubated with antimouse-CD34 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), -Flt3 phycoerythrin (PE), -Sca1 biotin, and -c-kit allophycocyanin (APC) antibodies or isotype-matched control antibodies (PharMingen, San Jose, CA), followed by illumination of biotinylated antibodies using streptavidin-PE-Texas red (Caltag). Cells were subsequently sorted for indicated phenotypes on either a FACSVantage or a FACSDiva (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA; Figure 1A). Analyses were performed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA).

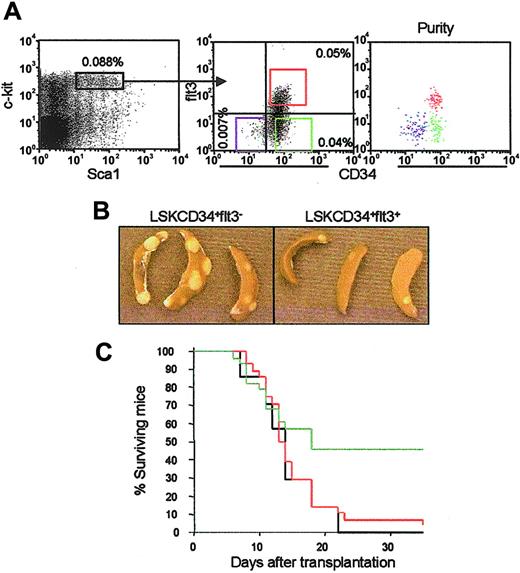

Distinct CFU-S and radioprotective potentials of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ ST-HSCs. (A) Lin– BM cells expressing high levels of c-kit and Sca-1 (left panel) were investigated for expression of CD34 and flt3 (middle panel). Percentages indicate frequencies (mean of 8 independent experiments) within total BM of LSKCD34–flt3– (lower left quadrant), LSKCD34+flt3– (lower right quadrant) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (upper right quadrant) cells. Boxes denote the sorting strategy used for each of the populations. Cells used in these studies were double or triple sorted, always resulting in 98% or higher purity (right panel). (B) Representative appearance of CFU-Sd11 colonies derived from LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Note the reduced number as well as average size of LSKCD34+flt3+-derived CFU-S colonies. Images were obtained with a Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). (C) Lethally irradiated mice were given transplants with 500 LSKCD34+flt3– (green) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (red) cells, and subsequently monitored daily for survival. Mice receiving no cells but injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) served as negative controls (black). Results are from 2 experiments in which a total of 28 mice underwent transplantation in each group.

Distinct CFU-S and radioprotective potentials of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ ST-HSCs. (A) Lin– BM cells expressing high levels of c-kit and Sca-1 (left panel) were investigated for expression of CD34 and flt3 (middle panel). Percentages indicate frequencies (mean of 8 independent experiments) within total BM of LSKCD34–flt3– (lower left quadrant), LSKCD34+flt3– (lower right quadrant) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (upper right quadrant) cells. Boxes denote the sorting strategy used for each of the populations. Cells used in these studies were double or triple sorted, always resulting in 98% or higher purity (right panel). (B) Representative appearance of CFU-Sd11 colonies derived from LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Note the reduced number as well as average size of LSKCD34+flt3+-derived CFU-S colonies. Images were obtained with a Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). (C) Lethally irradiated mice were given transplants with 500 LSKCD34+flt3– (green) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (red) cells, and subsequently monitored daily for survival. Mice receiving no cells but injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) served as negative controls (black). Results are from 2 experiments in which a total of 28 mice underwent transplantation in each group.

In vivo reconstitution in the congenic mouse model

Competitive reconstitution assays using the congenic CD45.1/CD45.2 mouse model was a modification of a previously reported protocol.16 Using this model, LSK subsets can be purified from C57Bl/6 mice expressing one of the CD45 (common leukocyte antigen) isoforms and subsequently specifically identified through their ability to multilineage reconstitute transplanted C57Bl/6 recipients expressing another CD45 isoform, because B (B220+), T (CD4/CD8+), and myeloid (Gr1/Mac-1+) cells all ubiquitously express the CD45 antigen. Briefly, 50 fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) purified LSK cells (CD45.2) of different subfractions and 2 × 105 unfractionated BM cells (CD45.1) were coinjected into lethally irradiated (925 rad) recipient mice (CD45.1/CD45.2). At 3, 5, 7, and 16 weeks after transplantation, peripheral blood (PB) was analyzed to evaluate multilineage reconstitution abilities of test cells. To determine self-renewal potentials of test cells, secondary transplantations were performed as described previously.18 In short-term reconstitution experiments, 500 LSKCD34–flt3– or LSKCD34+flt3– cells and 1 × 105 unfractionated BM cells were transplanted into each recipient. In these experiments, reconstitution of BM, spleens, and PB were analyzed at days 8 and 11. For evaluation of spleen colony-forming unit (CFU-S) abilities, 50 FACS-purified cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients, and 8 or 11 days after transplantation, macroscopic colonies were identified and evaluated after fixation of spleens in Tellesniczky fixative. Radioprotection experiments were performed by transplanting 500 test cells into lethally irradiated mice, with subsequent daily recording of surviving recipients. To investigate the hierarchical relationship between LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells, 1000 CD45.2+ cells of each subset were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. At 14 days after transplantation, spleen and BM cells from recipients were harvested and evaluated by flow cytometry for regeneration of donor-derived cells with LSKflt3–/+ phenotypes.

Phenotypic analysis

Multilineage PB analyses at indicated time points were performed as described.18 To evaluate the distribution of side population (SP) cells within the LSKCD34–/+flt3–/+ compartments, lineage-depleted BM cells were stained with 2.5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) as described,19 followed by cell surface stainings and analysis on a FACSDiva.

In vitro assays

Unless otherwise indicated, all cytokines were used at 20 to 50 ng/mL. Single-cell cultures were performed as described.16 Briefly, single cells were cultured under serum-free conditions and supplemented with indicated individual cytokines or a multicytokine combination including c-kit ligand (KL), the fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand (FL), thrombopoietin (TPO), and interleukin 3 (IL-3). Wells were scored for total and high proliferative (> 50% of well covered with cells) clones after 10 days of incubation (at 37°C, 98% humidity, and 5% CO2). When investigating the survival-promoting activities of individual cytokines, single cells were preincubated with 100 ng/mL of either KL, FL, or TPO (or without any cytokine) for 5 days, before addition of the multicytokine cocktail into each well.20 Scoring was performed after 10 days of additional culture. The myeloid (granulocyte-macrophage) differentiation potential of sorted LSK populations was evaluated at the single-cell level and in cultures initiated with 100 cells each, in both cases using a medium containing fetal calf serum supplemented with KL plus FL plus IL-3 plus IL-6 plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) plus granulocyte colony-stimulating (G-CSF). Following indicated times of culture, cell counts, cytospin preparations, and May-Grünwald-Giemsa stainings were performed. The number of granulocytes produced per initiating cell was calculated by: % granulocytes (within 400 cells/slide) × fold expansion/100.

Results

Fractionation of the LSK HSC pool into distinct CD34–flt3–, CD34+flt3–, and CD34+flt3+ subpopulations

Although representing only 0.05% to 0.1% of total adult BM cells, the LSK compartment contains all LT-HSCs.3-5 Whereas the LSK LT-HSC population lacks CD34 and flt3 expression,7,16,17 more than 90% of LSK cells are CD34+ with short-term repopulating stem and progenitor cell activities.7 However, the potential heterogeneity of the LSKCD34+ ST-HSC pool has not been directly investigated. On costaining with anti-CD34 and anti-flt3 antibodies, 3 rather than 2 distinct LSK populations could be observed in adult BM: LSKCD34–flt3–, LSKCD34+flt3–, and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells, representing 0.007%, 0.04%, and 0.05% of total BM cells, respectively (Figure 1A). LSKCD34–flt3– cells are identical to the previously described LSKCD34– LT-HSCs.7 LSKflt3+ cells (all coexpressing CD34; Figure 1A) have also recently been described and suggested to contain ST-HSCs.16,17 LSKCD34+flt3– cells, representing a novel subpopulation within the CD34+ short-term progenitor/stem cell compartment, were isolated by FACS to high purities (> 98%; Figure 1A) and investigated in a number of assays side by side with the LSKCD34+flt3+ population to establish to what degree they represent functionally distinct or overlapping ST-HSC subpopulations.

Distinct CFU-S and radioprotective abilities of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells

The in vivo clonogenic CFU-S assay detects primitive multipotent progenitor/stem cells capable of rapidly producing myeloerythroid cells in vivo,21 with late-appearing CFU-Sd11-12 cells being derived from more primitive progenitor/stem cell populations than CFU-Sd8 cells.9,22 Thus, the ability to produce CFU-S cells is tightly correlated with the capacity to rapidly reconstitute lethally ablated recipients, and in agreement with this, highly purified LT-HSCs have been demonstrated to have very limited CFU-S (in particular CFU-Sd8) and radioprotective capacities.7,11,12 For instance, highly purified LSKCD34– cells have little CFU-S activity and provide poor radioprotection when transplanted alone.7,10,11 In contrast, a biologically and clinically potent ST-HSC population would be expected to be highly enriched for CFU-Sd11-12 and, in particular, CFU-Sd8 progenitors, and thereby rapidly reconstitute the myeloerythroid progenitors required to rescue ablated recipients from BM failure.9

A striking quantitative and qualitative difference was observed between the CFU-S potentials of LSKCD34+flt3– and LKCD34+flt3+ cells, particularly apparent at day 8, in that as many as 1 of 26 LSKCD34+flt3– cells were able to form macroscopically visible CFU-Sd8 as compared to only 1 of 950 LSKCD34+flt3+ cells (only one colony observed in a total of 19 mice transplanted with 50 cells each; Table 1). Noteworthy, as many as 1 of 9 LSKCD34+flt3– cells produced large CFU-Sd11, the highest frequency reported for any identified progenitor/stem cell population, whereas only 1 of 85 LSKCD34+flt3+ cells had CFU-Sd11 potential (Table 1). Furthermore, CFU-Sd11 colonies derived from LSKCD34+flt3+ cells were found to be considerably smaller than the typical very large CFU-Sd11 colonies from LSKCD34+flt3– cells (Figure 1B).

Frequencies of LSKCD34+flt3- and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells generating CFU-S colonies at days 8 and 11

. | CFU-Sd8 . | CFU-Sd11 . |

|---|---|---|

| LSKCD34+flt3- | 1/26 | 1/9 |

| LSKCD34+flt3+ | 1/950 | 1/85 |

. | CFU-Sd8 . | CFU-Sd11 . |

|---|---|---|

| LSKCD34+flt3- | 1/26 | 1/9 |

| LSKCD34+flt3+ | 1/950 | 1/85 |

Lethally irradiated mice were given transplants of 50 LSKCD34+flt3- or LSKCD34+flt3+ cells each. Results are from 2 experiments with a total of 11 to 20 recipients/group.

Although committed myeloerythroid progenitors are both required and sufficient to radioprotect lethally myeloablated recipients, almost 50 000 common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) must be transplanted to rescue 50% of lethally irradiated recipients,9 suggesting that more primitive progenitor/stem cells are required to continuously replenish these, even in the short term. Whereas LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs have been demonstrated to have poor radioprotective capacity,7,10,11 we here found, in agreement with their prominent CFU-Sd8 and CFU-Sd11 capacities, that as few as 500 LSKCD34+flt3– cells were sufficient to radioprotect 13 of 28 (46%) lethally irradiated mice at day 30 (Figure 1C). In contrast, of 28 recipients given transplants of 500 LSKCD34+flt3+ cells, only 1 (4%) survived. PB analysis of mice surviving for 10 weeks following transplantation of LSKCD34+flt3– cells showed donor-derived lymphoid cells, whereas long-term myeloid reconstitution was exclusively recipient derived (data not shown), demonstrating that the short-term protective effect of LSKCD34+flt3– cells does not depend on the presence of cotransplanted LT-HSCs. Thus, the only cells within the LSK compartment fulfilling the requirements of ST-HSCs to rapidly reconstitute myeloerythropoiesis and radioprotect BM-ablated mice, are LSKCD34+flt3– cells.

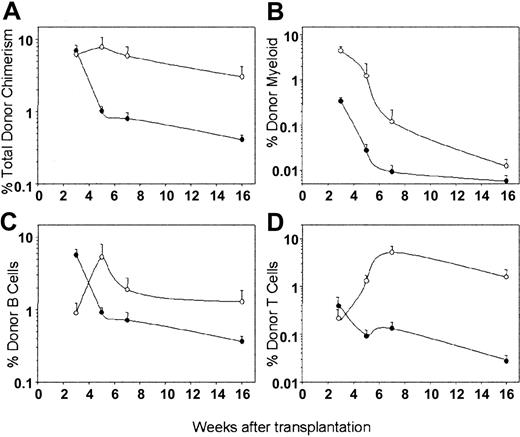

Distinct short-term multilineage reconstituting abilities of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells

To directly evaluate and compare the in vivo multilineage repopulating abilities of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells, we transplanted as few as 50 highly purified (CD45.2) cells of each subpopulation in competition with 200 000 unfractionated BM (CD45.1) cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1/2 mice. PB cells were analyzed for multilineage lymphomyeloid reconstitution 3, 5, 7, and 16 weeks after transplantation. Three weeks after transplantation, mice given 50 LSKCD34+flt3– or LSKCD34+flt3+ cells were reconstituted at high and comparable levels with CD45.2 cells (6%-7%; Figure 2A). However, the contribution of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells to reconstitution of myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis showed striking differences (Figure 2B-D). Whereas in agreement with previous studies,16 LSKCD34+flt3+ cells reconstituted primarily lymphopoiesis at this time (83% B cells, 7% T cells, and 10% myeloid cells), LSKCD34+flt3– cells efficiently reconstituted myeloid (79%) and less efficiently lymphoid lineages (18% B and 3% T cells). By week 5, the total level of LSKCD34+flt3+-derived reconstitution dropped to a mean of only 1% and was restricted to lymphoid reconstitution because significant myeloid cells were no longer detectable (below background of 0.1%; Figure 2A-D). In striking contrast, by week 5, LSKCD34+flt3–-derived reconstitution had further increased, including myeloid, B, and T cells. Subsequent PB analyses at 7 and 16 weeks after transplantation of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells showed decreased total reconstitution levels for both populations with time. This was accompanied with a shift in lineage distribution toward almost exclusively B and T cells (Figure 2B-D), and by week 16, no myeloid reconstitution could be observed from LSKCD34+flt3+ or LSKCD34+flt3– cells, suggesting that neither of these populations contains LT-HSCs. In fact, of a total of 88 mice given transplants with 50 to 500 LSKCD34+flt3– cells (total of 27 350 cells transferred), only 1 recipient demonstrated long-term myeloid reconstitution, and on secondary transplantations performed 16 weeks after the primary transplantations, no recipients showed multilineage reconstitution derived from LSKCD34+flt3+ or LSKCD34+flt3– cells (data not shown).

In vivo multilineage reconstitution by LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ ST-HSCs. Lethally irradiated C57bl/6 CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were given transplants with 50 CD45.2 LSKCD34+flt3– (○) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (•) cells together with 200 000 CD45.1 unfractionated BM cells. Figure shows percent contribution to total PB cells of (A) total, (B) myeloid, (C) B-cell, and (D) T-cell reconstitution derived from transplanted LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells 3, 5, 7, and 16 weeks after transplantation. All data represent the means (SEM) of 16 to 18 mice per group from 3 experiments.

In vivo multilineage reconstitution by LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ ST-HSCs. Lethally irradiated C57bl/6 CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were given transplants with 50 CD45.2 LSKCD34+flt3– (○) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (•) cells together with 200 000 CD45.1 unfractionated BM cells. Figure shows percent contribution to total PB cells of (A) total, (B) myeloid, (C) B-cell, and (D) T-cell reconstitution derived from transplanted LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells 3, 5, 7, and 16 weeks after transplantation. All data represent the means (SEM) of 16 to 18 mice per group from 3 experiments.

Myeloid differentiation potential and stem-cell cytokine responsiveness of LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells

The ability to form CFU-Ss and radioprotect has been demonstrated to primarily reflect a megakaryocyte-erythroid reconstitution potential.9 However, a candidate ST-HSC population must also at the single-cell level possess a granulocyte-macrophage differentiation potential. Virtually all LSKCD34+flt3+ and LSKCD34+flt3– single cells showed a high proliferative potential to a cocktail of early acting and myeloid growth factors (Figure 3A). By day 9 to 10, 97% and 86% of single LSKCD34+flt3– cells and 87% and 95% of LSKCD34+flt3+ cells produced granulocytes and macrophages, respectively (Figure 3B), in agreement with previous studies.16

Myeloid differentiation potential and responsiveness to the stem cell factors c-kit ligand and thrombopoietin. (A) Clonogenic (□; total cloning frequency) and high proliferative (▪; > 50% of well covered by cells) potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Mean (SD) values from 3 experiments. (B) Myeloid potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (□) cells. Data show the frequencies of cells with granulocyte (G) and macrophage (Mϕ) potentials (means [SD] of 3 experiments). May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cultured cells derived from single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells are shown in lower panels. Images were visualized under an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a 100×/1.30 oil objective lens, an Olympus DP70 digital camera, and DP controller 1.1.1.65 software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (C) Frequencies of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (▪) cells surviving in response to the stem cell factors KL, TPO, and FL. Mean values (SD) from 3 experiments.

Myeloid differentiation potential and responsiveness to the stem cell factors c-kit ligand and thrombopoietin. (A) Clonogenic (□; total cloning frequency) and high proliferative (▪; > 50% of well covered by cells) potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Mean (SD) values from 3 experiments. (B) Myeloid potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (□) cells. Data show the frequencies of cells with granulocyte (G) and macrophage (Mϕ) potentials (means [SD] of 3 experiments). May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cultured cells derived from single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells are shown in lower panels. Images were visualized under an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a 100×/1.30 oil objective lens, an Olympus DP70 digital camera, and DP controller 1.1.1.65 software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (C) Frequencies of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (▪) cells surviving in response to the stem cell factors KL, TPO, and FL. Mean values (SD) from 3 experiments.

Both KL and TPO have, through lack of function studies, been demonstrated to be nonredundant regulators of LT-HSC numbers and function, and their receptors are highly expressed on LT-HSCs.23-26 These cytokines have also been demonstrated to play key roles in regulation of early megakaryocyte and erythroid development,23,27 and to act as viability factors for primitive progenitors and HSCs, including LT-HSCs.20,28-30 We therefore hypothesized that candidate ST-HSCs, as LT-HSCs, should respond efficiently to KL and TPO. Noteworthy, KL efficiently promoted survival of LSKCD34+flt3– cells (Figure 3C) as previously demonstrated for LT-HSCs,16,29,30 whereas the effect on LSKCD34+flt3+ cells was much less, despite LSKCD34+flt3+ and LSKCD34+flt3– cells expressing comparable and high levels of c-kit (Figure 1A). Similarly, TPO promoted survival of LSKCD34+flt3– cells, but had absolutely no such effect on LSKCD34+flt3+ cells (Figure 3C). In contrast and as previously shown,16 FL promoted survival of LSKCD34+flt3+ cells but as expected not LSKCD34+flt3– cells. Thus, LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells have distinct TPO and KL response patterns.

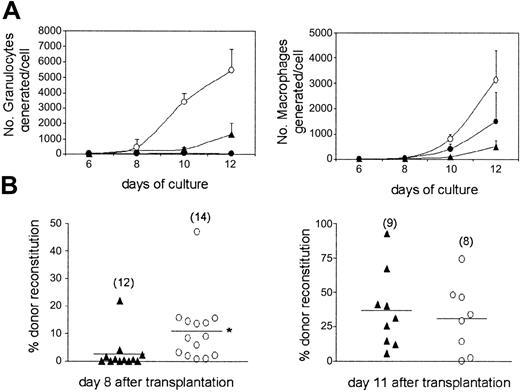

Short-term reconstituting potential of LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs and LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs

Although previous studies of CFU-S and radioprotective abilities have suggested that LT-HSCs are less efficient than ST-HSCs at rapidly reconstituting myelopoiesis,7,11,12 this has not been investigated directly, in part due to the challenge of performing reconstitution analysis only a few days following transplantation. Using optimal conditions for in vitro myeloid differentiation, we first compared the extent and kinetics of granulocyte and macrophage production of LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs and LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs (Figure 4A). Noteworthy, whereas LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs produced large numbers of mature granulocytes by day 8, significant granulocyte production from LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs was first observed at day 10. By day 12 LSKCD34+flt3– cells had generated more than 5000 granulocytes/cell and LSKCD34–flt3– cells only 1000. A similar pattern was observed for macrophage development (Figure 4A). Strikingly, although virtually all LSKCD34+flt3+ and LSKCD34+flt3– cells at the single-cell level have a granulocyte and macrophage potential,16 LSKCD34+flt3+ cells demonstrated a dramatically reduced ability to produce granulocytes when compared to LSKCD34+flt3– cells (30 versus 5000 granulocytes produced per cell at day 12), whereas the macrophage potential was more comparable (Figure 4A).

Accelerated myeloid reconstitution on transplantation of LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs. (A) Number of granulocytes (left) and macrophages (right) generated in vitro per initiating LSKCD34–flt3– (▴), LSKCD34+flt3– (○), or LSKCD34+flt3+ (•) cell over time. Data are from 3 experiments. (B) In vivo competitive reconstituting ability of LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs at day 8 (left) and 11 (right) following transplantation of 500 cells, in competition with 1 × 105 total BM cells. Data are from 8 to 14 mice from 2 experiments, as indicated in parentheses. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. *P < .05.

Accelerated myeloid reconstitution on transplantation of LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs. (A) Number of granulocytes (left) and macrophages (right) generated in vitro per initiating LSKCD34–flt3– (▴), LSKCD34+flt3– (○), or LSKCD34+flt3+ (•) cell over time. Data are from 3 experiments. (B) In vivo competitive reconstituting ability of LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs at day 8 (left) and 11 (right) following transplantation of 500 cells, in competition with 1 × 105 total BM cells. Data are from 8 to 14 mice from 2 experiments, as indicated in parentheses. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. *P < .05.

Next, we compared the in vivo short-term myeloid reconstituting ability of LT LSKCD34–flt3– and ST LSKCD34+flt3– cells. In agreement with the in vitro data, ST LSKCD34+flt3– cells were significantly better at reconstituting at day 8 than LT LSKCD34–flt3– cells (11% and 2.7% reconstitution, respectively, P < .05; Figure 4B). In agreement with this, LSKCD34+flt3– cells were also more than 5-fold enriched for CFU-Sd8 activity when compared to LSKCD34–flt3– cells (Table 2). However, at day 11 the reconstitution levels and CFU-S activities were comparable for the 2 populations (Figure 4B). Thus, ST LSKCD34+flt3– cells are (on a cell-to-cell basis) significantly more efficient than LT LSKCD34–flt3– cells at rapidly reconstituting myelopoiesis in lethally ablated recipients.

Frequencies of cells generating CFU-S colonies

. | CFU-Sd8 . | CFU-Sd11 . |

|---|---|---|

| LSKCD34-flt3- | 1/175 | 1/22 |

| LSKCD34+flt3- | 1/32 | 1/15 |

. | CFU-Sd8 . | CFU-Sd11 . |

|---|---|---|

| LSKCD34-flt3- | 1/175 | 1/22 |

| LSKCD34+flt3- | 1/32 | 1/15 |

CFU-S day-8 and day-11 activities of LSKCD34-flt3- LT-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3- ST-HSCs. Results are from 2 experiments with a total of 14 to 25 recipients given transplants of 50 cells each.

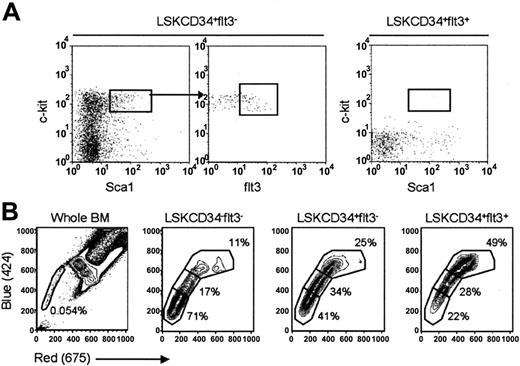

Hierarchical relationship among LSKCD34–flt3–, LSKCD34+flt3–, and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells

Based on their lineage and reconstitution potentials, one could postulate a hierarchical relationship, in which LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs give rise to less primitive LSKCD34+flt3+ multipotent progenitors (MPPs). To test this hypothesis and the ability of each of these populations to self-renew, LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice and subsequently BM (Figure 5A) and spleens (data not shown) were investigated for the presence of donor-derived LSKflt3– and LSKflt3+ cells 2 weeks after transplantation. LSKCD34+flt3– cells regenerated LSKflt3– as well as LSKflt3+ cells (Figure 5A), whereas following 2 weeks no (flt3+ or flt3–) LSK cells were detected in mice given transplants with LSKCD34+flt3+ cells (Figure 5A), confirming the hierarchical relationship between these 2 populations.

Hierarchical relationship and Hoechst efflux capacities of ST- and LT-HSCs. (A) A total of 1000 CD45.2 LSKCD34+flt3– (left) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (right) cells were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients, and 14 days later the BM of recipients was evaluated for regeneration of CD45.2 cells with LSKflt3– and LSKflt3+ phenotypes. Figure depicts BM analysis of one representative recipient of each cell population. Results are from 1 of 2 experiments with 3 recipients receiving LSKCD34+flt3+ cells and 4 recipients receiving LSKCD34+flt3– cells. (B) Lineage-depleted BM cells were stained with Hoechst and antibodies against Sca1, c-kit, CD34, and flt3. Cells were gated as LSKCD34–flt3–, LSKCD34+flt3–, and LSKCD34+flt3+ as indicated, and dual wavelength Hoechst fluorescence investigated for each population. Plots are from 1 representative experiment of 3. Left panel shows Hoechst profile of unfractionated BM cells.

Hierarchical relationship and Hoechst efflux capacities of ST- and LT-HSCs. (A) A total of 1000 CD45.2 LSKCD34+flt3– (left) or LSKCD34+flt3+ (right) cells were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients, and 14 days later the BM of recipients was evaluated for regeneration of CD45.2 cells with LSKflt3– and LSKflt3+ phenotypes. Figure depicts BM analysis of one representative recipient of each cell population. Results are from 1 of 2 experiments with 3 recipients receiving LSKCD34+flt3+ cells and 4 recipients receiving LSKCD34+flt3– cells. (B) Lineage-depleted BM cells were stained with Hoechst and antibodies against Sca1, c-kit, CD34, and flt3. Cells were gated as LSKCD34–flt3–, LSKCD34+flt3–, and LSKCD34+flt3+ as indicated, and dual wavelength Hoechst fluorescence investigated for each population. Plots are from 1 representative experiment of 3. Left panel shows Hoechst profile of unfractionated BM cells.

An alternative way to identify and isolate mouse HSCs is based on their ability to efflux the dye Hoechst 33342, presumably through high levels of multidrug resistance proteins, as evidenced through appearance of a so-called side population (SP).31 If various degrees of “stemcellness” are associated with distinct degrees of dye efflux capabilities, as recently suggested,32 LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs might display different SP profiles. In agreement with previous results,31 in 5 independent experiments we found that 0.06% ± 0.03% of total BM cells have an SP phenotype (Figure 5B) and a reconstitution potential comparable to that of total LSK cells (S.E.W.J. et al, unpublished data, 2001). Noteworthy, whereas the majority of LSKCD34–flt3– cells were SPlo, LSKCD34+flt3– cells were predominantly SPint, and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells mostly SPhi (Figure 5B), supporting that the ability to efflux Hoechst 33342 is sustained, but gradually reduced, through commitment of LT-HSCs (LSKCD34–flt3–) to ST-HSCs (LSKCD34+flt3–) and MPPs (LSKCD34+flt3+).

Discussion

Despite almost 4 decades of successful application in patients with cancer, hematologic disorders, and immunodeficiencies, the treatment-related mortality and morbidity following allogeneic HSC (BM or PB) transplantation remains very high, in part as a consequence of graft-versus-host disease, and in part reflecting the toxic BM conditioning required to ablate recipients of HSC transplants.33,34 The severe cytopenias induced by BM ablation translate into high risks of developing fatal infections and bleedings, until transplanted cells have produced sufficient myeloerythroid offspring. Purified LT-HSCs, although sufficient and crucial for sustaining life-long hematopoiesis, appear to require too long a time to produce the critically needed mature myeloerythroid cells to allow them to efficiently protect mice from lethal irradiation,7,10-12 unless transplanted at high doses.13 On the other hand, committed myeloerythroid progenitors, although ultimately responsible for mediating radioprotection, lack self-renewing potential, and are therefore required at very high numbers,9 suggesting that self-renewing ST-HSCs downstream of LT-HSCs might be crucial for rapid and continuous replenishment of myeloerythroid progenitors.

Although the existence of ST-HSCs has been demonstrated, their exact identity and functional characteristics have remained much less well defined than those of LT-HSCs.7,11,14 In the present studies we identified a distinct LSKCD34+flt3– cell population representing 0.04% of adult BM cells, which fulfills all criteria of ST-HSCs. In contrast to LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs7,10,11 and LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs, LSKCD34+flt3– cells were highly enriched in CFU-Sd8 and radioprotective activities. Approximately 100-fold more committed myeloerythroid progenitors (common myeloid and megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors; CMPs and MEPs, respectively35 ) are required to mediate the same level of protection as LSKCD34+flt3– cells.9 Noteworthy, we also demonstrate for the first time that (LSKCD34+flt3–) ST-HSCs are (on a cell-to-cell basis) also much more efficient than LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs at rapidly reconstituting myelopoiesis. Taking into account also the size of the LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSC, LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSC, LSKCD34+flt3+ MPP, CMP,35 and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP)35 compartments (0.007%, 0.04%, 0.05%, 0.2%, and 0.1%, of total BM nucleated cells, respectively), it is evident that the vast majority of BM short-term reconstituting, radioprotective, and CFU-Sd11-12 activities are derived from LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs.

Despite the fact that both LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells have a combined myeloid and lymphoid differentiation potential and are equally efficient at rapidly reconstituting total blood cell levels in lethally irradiated recipients at 3 weeks after transplantation, their reconstitution pattern differed dramatically, in lineage composition as well as durability. At 3 weeks after transplantation LSKCD34+flt3– cells gave rise, almost exclusively, to high levels of myeloid progeny. In striking contrast, at this time LSKCD34+flt3+ cells produced very limited numbers of myeloid cells but were more efficient at rapidly reconstituting lymphopoiesis than LSKCD34+flt3– cells. At 5 weeks after transplantation the contribution of LSKCD34+flt3– cells (in competition with total BM cells) to total PB reconstitution was further enhanced, whereas LSKCD34+flt3+ reconstitution was reduced almost 10-fold. Furthermore, at this time LSKCD34+flt3– cells contributed 5- to 15-fold more to reconstitution not only of myeloid, but also B and T cells, than LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. The superior ability of LSKCD34+flt3– cells to rapidly reconstitute myelopoiesis on transplantation was also reflected in LSKCD34+flt3– cells much more efficiently and rapidly producing mature granulocytes in vitro, than LSKCD34+flt3+ and LSKCD34–flt3– cells, although all 3 populations possess a granulocyte-macrophage differentiation potential at the single-cell level. Finally, in vivo transplantation experiments demonstrated the hierarchical relationship between LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Thus, within the LSK HSC compartment, only LSKCD34+flt3– cells fulfill the criteria of multipotent ST-HSCs capable of rapidly reconstituting erythromyelopoiesis, and as a consequence, efficiently protecting mice from lethal myeloablation. LSKCD34+flt3+ cells might sustain some ST-HSC potential because they possessed some CFU-Sd11 activity, although much less than LSKCD34+flt3– cells.

Although our data suggest that both LSKCD34+ populations possess a prominent multilineage short-term reconstitution potential, they demonstrate that adult BM LSKCD34+flt3+ cells in contrast to LSKCD34+flt3– cells have little or no true ST-HSC activity, in apparent contrast with previous studies suggesting that LSKflt3+ cells coexpressing Thy1.1 are ST-HSCs.17 Although a fraction of LSKCD34+flt3+ cells (coexpressing Thy1.1) might be ST-HSCs, the data presented herein strongly implicate that most ST-HSCs in adult BM are LSKCD34+flt3–/10. In support of this, LSK(CD34+)flt3– cells are all Thy1.1lo (in C57bl/6 strains expressing Thy1.1,17 and D.B., unpublished data, 2004). In contrast, the LSKCD34+flt3+ population that we define as possessing predominantly multipotent progenitor activity contains both Thy1.1– and Thy1.1lo cells, with the mean expression level of Thy1.1 being down-regulated when compared to LSK(CD34+) flt3– cells.17 Furthermore, whereas most LSKCD34+flt3– cells in addition to a combined B, T, G, and M lineage potential possess a megakaryocyte/erythroid potential, virtually all LSKCD34+ BM cells expressing high levels of flt3 lack the option to adapt a megakaryocyte/erythroid fate (J.A. and S.E.W.J., unpublished observation, 2004). Importantly, in the studies of Christensen et al,17 short- and long-term lymphomyeloid but not megakaryocyte/erythroid reconstitution potentials were evaluated, neither were the radioprotective and CFU-S potentials. Thus, although both LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+ flt3+ cells are capable of rapid and prominent short-term lymphomyeloid reconstitution, only the LSKCD34+flt3– population fulfills the criteria of being highly enriched in pluripotent ST-HSC activity.

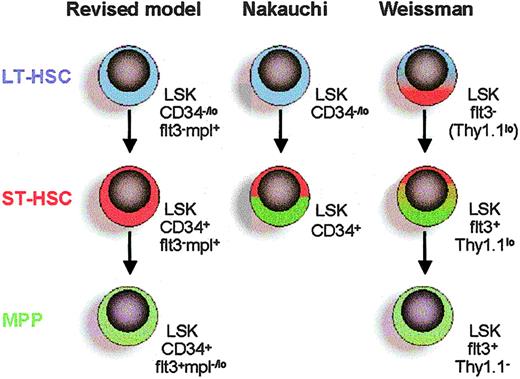

The current studies unequivocally demonstrate that the LSKCD34+ ST-HSC pool identified by Osawa et al7 can be further delineated into LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs with distinct biologic properties (Figure 6). Furthermore, although our data confirm that LT-HSCs are LSKflt3– as defined recently,16,17 they also demonstrate that LSKflt3– HSCs are heterogeneous and contain LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs as well as LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs (Figure 6). Thus, through differential expression of CD34 and flt3, the LSK HSC compartment can be subdivided into 3 functionally distinct and hierarchical-related subpopulations: LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs, LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs, and LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs (Figure 6). Of particular interest, these 3 populations differed markedly in their responsiveness to the ligands for c-kit and c-mpl (TPO receptor). Whereas LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs as LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs (D.B. and S.E.W.J., unpublished observations, 2002) were highly KL responsive, LSKCD34+flt3+ cells showed a reduced KL response. The difference in response to TPO was even more striking because LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs and LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs (D.B. and S.E.W.J., unpublished observations, 2002) were TPO responsive, whereas LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs showed no TPO response (Figure 6).

Revised model of Lin–Sca1+kithi HSC hierarchy based on differential expression of CD34, flt3, and c-mpl. LT-HSCs (blue) differentiate into ST-HSCs (red) with reduced self-renewing capacity but enhanced ability to rapidly reconstitute myelopoiesis. The ST-HSC gives rise to a multipotent progenitor (MPP; green) with sustained lymphomyeloid potential, but that on transplantation rapidly and preferentially reconstitutes lymphopoiesis rather than myelopoiesis. Direct comparisons are made with 2 previous key studies on LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs.7,17 Nakauchi and coworkers7 defined ST-HSCs as LSKCD34+ cells, without further subfractionation. Weissman and coworkers17 defined LT-HSCs as LSKflt3–, which the present studies show can be subfractionated into LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs. In addition, the population of LSKflt3+Thy1.1lo ST-HSCs17 is likely to overlap with the population of LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs. Expression of c-mpl (TPO receptor) of different subpopulations is based on the present studies of TPO responsiveness and previous studies of c-mpl expression on HSCs.25

Revised model of Lin–Sca1+kithi HSC hierarchy based on differential expression of CD34, flt3, and c-mpl. LT-HSCs (blue) differentiate into ST-HSCs (red) with reduced self-renewing capacity but enhanced ability to rapidly reconstitute myelopoiesis. The ST-HSC gives rise to a multipotent progenitor (MPP; green) with sustained lymphomyeloid potential, but that on transplantation rapidly and preferentially reconstitutes lymphopoiesis rather than myelopoiesis. Direct comparisons are made with 2 previous key studies on LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs.7,17 Nakauchi and coworkers7 defined ST-HSCs as LSKCD34+ cells, without further subfractionation. Weissman and coworkers17 defined LT-HSCs as LSKflt3–, which the present studies show can be subfractionated into LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs and LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs. In addition, the population of LSKflt3+Thy1.1lo ST-HSCs17 is likely to overlap with the population of LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs. Expression of c-mpl (TPO receptor) of different subpopulations is based on the present studies of TPO responsiveness and previous studies of c-mpl expression on HSCs.25

Our studies confirm that virtually all SP cells have an LSK HSC phenotype, but also demonstrate, in agreement with recent studies,32 a hierarchical relationship in the SP profiles of LSKCD34–flt3– LT-HSCs, LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSCs, and LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs, suggesting that the ability to efficiently efflux drugs is sustained but gradually reduced through these 3 stages of HSC development.

In conclusion, we have, in adult mouse BM, identified a novel LSKCD34+flt3– ST-HSC population that on transplantation reveals a potent and unique ability to rapidly reconstitute myelopoiesis and rescue lethally ablated recipients and that gives rise to LSKCD34+flt3+ MPPs capable of rapidly reconstituting lymphopoiesis. The biologic significance and clinical potentials of these 2 distinct short-term repopulating cells are obvious, and the ability to prospectively identify and purify these will now facilitate identification of their human counterparts as well as delineation of the genetic pathways regulating succession through these distinct stages of early hematopoietic development.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 30, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2159.

Supported by grants from ALF (Governmental Public Health Grant), Alfred Österlund Foundation, Funds of Lunds Sjukvårdsdistrikt, the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Society of Pediatric Cancer, and the Tobias Foundation. The Lund Stem Cell Center is supported by a Center of Excellence grant from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

L.Y. and D.B. contributed equally to this work.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank L. Wittman and I. Grundström Åstrand for expert technical assistance; A. Fossum and Z. Ma for FACS sorting; L. Thorén for stem cell purifications; and A. Gustafsson for performing in vitro cell differentiation studies. We thank Dr Irv Weissman for helpful discussions.

![Figure 3. Myeloid differentiation potential and responsiveness to the stem cell factors c-kit ligand and thrombopoietin. (A) Clonogenic (□; total cloning frequency) and high proliferative (▪; > 50% of well covered by cells) potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells. Mean (SD) values from 3 experiments. (B) Myeloid potentials of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (□) cells. Data show the frequencies of cells with granulocyte (G) and macrophage (Mϕ) potentials (means [SD] of 3 experiments). May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cultured cells derived from single LSKCD34+flt3– and LSKCD34+flt3+ cells are shown in lower panels. Images were visualized under an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a 100×/1.30 oil objective lens, an Olympus DP70 digital camera, and DP controller 1.1.1.65 software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (C) Frequencies of single LSKCD34+flt3– (▪) and LSKCD34+flt3+ (▪) cells surviving in response to the stem cell factors KL, TPO, and FL. Mean values (SD) from 3 experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/105/7/10.1182_blood-2004-06-2159/6/m_zh80070576280003.jpeg?Expires=1769819754&Signature=iEDH2CZ9a78Jw6qzS7APK2E2psAsXvYET5YFMe8sC-F7oj~~BF03yL9-7sP5kMTBJ3p73lnXuZL027JL~pNKLawn-QY0M8DNYwhms23zfvbZp6XszaOXTnmHoN3GkMf3wqfe4rHPCFcd3NR72zDcCllUsBFWErLkVoFK9PoVsCbkBXvqcu-6iP7Hl55hDNZAxXeY56VdLdpvTo6c3TyfR1Xv19b7c8xDyR-Q~COkWksRszVllCZ4x3d0N3vRW1~8u~Z4gWhLHUdKtfEFoLHBVD1rYqS2ffPqjkxOhO8ThYCOquMNyTFGT9QnuBBhApQfn9fww-8pv6yvsXha~CexTQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal