Abstract

Apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand (FasL) interaction with Fas receptor plays a pivotal regulatory role in immune homeostasis, immune privilege, and self-tolerance. FasL, therefore, has been extensively exploited as an immunomodulatory agent to induce tolerance to both autoimmune and foreign antigens with conflicting results. Difficulties associated with the use of FasL as a tolerogenic factor may arise from (1) its complex posttranslational regulation, (2) the opposing functions of different forms of FasL, (3) different modes of expression, systemic versus localized and transient versus continuous, (4) the level and duration of expression, (5) the sensitivity of target tissues to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis and the efficiency of antigen presentation in these tissues, and (6) the types and levels of cytokines, chemokines, and metalloproteinases in the extracellular milieu of the target tissues. Thus, the effective use of FasL as an immunomodulator to achieve durable antigen-specific immune tolerance requires careful consideration of all of these parameters and the design of treatment regimens that maximize tolerogenic efficacy, while minimizing the non-tolerogenic and toxic functions of this molecule. This review summarizes the current status of FasL as a tolerogenic agent, problems associated with its use as an immunomodulator, and new strategies to improve its therapeutic potential.

Fas/FasL system and immune homeostasis

The immune system functions in complex and dynamic microenvironments, where decisions pertaining to the survival and/or physical elimination of antigen-specific T-cell clones are critical to the establishment and maintenance of functional immunity. Activation-induced cell death (AICD) is the primary homeostatic mechanism used by the immune system to control T-cell responses, promote tolerance to self-antigens, and prevent autoimmunity.1-3 Following activation, T cells express Fas and Fas ligand (FasL) and upon repeated antigenic stimulation become sensitive to Fas/FasL-mediated autocrine and paracrine apoptosis (Figure 1).4-6 These 2 modes of apoptotic cell death serve to control the pool size of antigen-activated T-cell clones and regulate immune responses.7 All lymphocytes, including CD4+ and CD8+ T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells as well as dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils are subject to Fas/FasL-regulated immune homeostasis.8-11 Dysregulation of Fas/FasL-mediated AICD is associated with a series of pathophysiologic conditions, including degenerative and autoimmune disorders.12 Mouse strains that lack Fas (lpr) or express a defective FasL molecule (gld) suffer from severe lymphoproliferative disorders and autoimmunity,12,13 arising from the absence of antigen-induced clonal T-cell deletion in the periphery.14,15 Similarly, the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome in humans, an inherited disorder of lymphocyte homeostasis, is associated with the lack of AICD due to defects in Fas, FasL, and effector caspases.16

Physiologic regulation of immune responses by Fas/FasL-induced apoptosis. (A) Activation of T cells by the engagement of T-cell receptors (TCR) with the peptide/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) bimolecular complex in conjunction with the transduction of secondary signals (not shown) leads to the up-regulation of both Fas and FasL expression. (B) Upon repeated antigenic stimulation, T cells become sensitive to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis and undergo activation-induced cell death (AICD) via either autocrine or paracrine apoptosis. (C) Immune privileged tissues, such as the eye and testis, express FasL that triggers apoptosis in lymphocytes expressing Fas as a mechanism to prevent massive exacerbation of inflammatory reactions. Similarly, many tumor cells express FasL during disease progression and eliminate tumor reactive T cells as a means of immune evasion.

Physiologic regulation of immune responses by Fas/FasL-induced apoptosis. (A) Activation of T cells by the engagement of T-cell receptors (TCR) with the peptide/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) bimolecular complex in conjunction with the transduction of secondary signals (not shown) leads to the up-regulation of both Fas and FasL expression. (B) Upon repeated antigenic stimulation, T cells become sensitive to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis and undergo activation-induced cell death (AICD) via either autocrine or paracrine apoptosis. (C) Immune privileged tissues, such as the eye and testis, express FasL that triggers apoptosis in lymphocytes expressing Fas as a mechanism to prevent massive exacerbation of inflammatory reactions. Similarly, many tumor cells express FasL during disease progression and eliminate tumor reactive T cells as a means of immune evasion.

Fas is a 45-kDa, type I cell surface protein with an extracellular domain that binds to FasL and a cytoplasmic domain that transduces the death signal.17 Apoptosis is executed by the engagement and coaggregation of FasL with the Fas receptor on the cell surface followed by a series of intracellular molecular interactions that coordinate the hierarchical activation of caspases and cell death (Figure 2). Oligomerization of Fas following FasL engagement leads to the recruitment of Fas-associated proteins having death domains and the initiator procaspase-8 via its death effector domain into a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC).18-20 Procaspase-8 undergoes autoproteolysis in the DISC complex to generate an active caspase-8, which in turn initiates extrinsic apoptosis by converting inactive effector procaspases-3, -6, and -7 into active enzymes via transproteolysis and intrinsic apoptosis via cleavage of Bid, release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspase-9.18,21 Executioner caspases cleave various vital cellular substrates, which leads to cell death.

Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. (A) Binding of 3 FasL molecules with Fas leads to cell surface oligomerization, recruitment of the adapter protein FADD (Fas-associated protein with death domain), and procaspase-8 via its death effector domain (DED) into a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Activation of procaspase-8 by autocatalysis results in the initiation of extrinsic apoptosis by converting inactive effector procaspases-3, -6, and -7 into active enzymes via transproteolysis and intrinsic apoptosis via cleavage of Bid, release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspase-9 (not shown). (B) FasL is synthesized and stored as a membranous protein in vesicles by selected cell types. Upon activation by various physiologic stimuli, these vesicles are excreted from the cell and cause apoptosis of Fas-positive cells. (C) Wild-type FasL is cleaved from the cell surface by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and accumulates as a soluble protein (sFasL). (D) sFasL may transiently interact with proteins on the cell surface or the extracellular matrix (ECM) to form oligomeric structures with apoptotic activity. (E) sFasL as a soluble homotrimer cannot induce oligomerization of Fas and as such blocks apoptosis by competing with the membranous form for Fas binding.

Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. (A) Binding of 3 FasL molecules with Fas leads to cell surface oligomerization, recruitment of the adapter protein FADD (Fas-associated protein with death domain), and procaspase-8 via its death effector domain (DED) into a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Activation of procaspase-8 by autocatalysis results in the initiation of extrinsic apoptosis by converting inactive effector procaspases-3, -6, and -7 into active enzymes via transproteolysis and intrinsic apoptosis via cleavage of Bid, release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspase-9 (not shown). (B) FasL is synthesized and stored as a membranous protein in vesicles by selected cell types. Upon activation by various physiologic stimuli, these vesicles are excreted from the cell and cause apoptosis of Fas-positive cells. (C) Wild-type FasL is cleaved from the cell surface by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and accumulates as a soluble protein (sFasL). (D) sFasL may transiently interact with proteins on the cell surface or the extracellular matrix (ECM) to form oligomeric structures with apoptotic activity. (E) sFasL as a soluble homotrimer cannot induce oligomerization of Fas and as such blocks apoptosis by competing with the membranous form for Fas binding.

FasL is a 40-kDa, type II cell surface protein that is inducibly expressed in lymphocytes, particularly T cells,22 and constitutively expressed in cells present in immune privileged organs, such as Sertoli cells of the testis and epithelial cells in the eye.23,24 Inasmuch as FasL-mediated apoptosis is critical to peripheral T-cell homeostasis and cytotoxic effector mechanisms, inducible expression of FasL by T cells is tightly controlled at the transcriptional level through intricate interactions among various positive and negative transcriptional regulators. The positive regulators include nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT),25 early growth response gene 2 (Egr2)/Egr3,26 nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), activating protein-1 (AP-1),27 c-Myc,28 stimulating protein 1 (SP1),29 and cyclin B1/Cdk1.30 The negative regulators involve c-Fos31 and MHC class II transactivator (CIITA).32 Some of these regulators function by directly binding to their DNA response elements in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of FasL, while others may exert their effect indirectly by regulating other transcriptional factors. For example, NFAT can bind to the FasL promoter, directly induce expression or up-regulate the expression of Egr2/3, and cooperate with these transcriptional factors to induce the FasL expression.33

FasL expression and function are also regulated after translation. FasL protein is expressed in 3 distinct forms: (1) membranous form on the cell surface, (2) membranous form stored in intracellular microvesicles, which are excreted into the intercellular milieu in response to various physiologic stimuli, and (3) soluble form generated from the cleavage of the membranous molecule by matrix metalloproteinases within minutes of cell surface expression (Figure 2).34,35 With respect to apoptosis and immune regulation, the soluble and membranous forms differ in function. Membranous FasL is the primary mediator of apoptosis through formation of trimers and higher order structures on the cell surface. In contrast, soluble FasL (sFasL) can have proapoptotic, antiapoptotic, and neutrophil chemotactic functions, depending on the nature of other contextual mediators in the microenvironment.34,36-39 The antiapoptotic function is mediated by sFasL that competes with the membranous form for Fas binding. sFasL exists as a homotrimer, which is ineffective in coaggregating Fas. Therefore, its interaction with the receptor results in null signaling and lack of apoptosis.36,37 sFasL, however, can induce apoptosis following association/aggregation with extracellular matrix proteins,36,40 spontaneous aggregation,41,42 or when engineered to form tetramers and higher order structures (Figure 2).43

FasL as a tolerogenic agent to arrest autoimmunity and destructive alloreactive responses

The immune privilege status of various organs, such as eyes and testes, is partially established by their expression of high levels of FasL (Figure 1C).23,24 FasL is constitutively expressed in the thymus where it plays an important role in the ontogenesis and negative selection of T cells,2 in activated lymphocytes where it contributes to the establishment of peripheral tolerance,14 and on various tumor cells to serve as a mechanism of immune evasion by inducing apoptosis of tumor-specific T cells.44 The pivotal role FasL plays in AICD,1-3 immune privilege, tolerance to self antigens,45 and immune evasion by tumors,46,47 has led to intensive efforts to use the Fas/FasL system as an immunomodulatory approach to induce tolerance to auto and transplantation antigens for the treatment/prevention of autoimmunity and graft rejection.

Systemic immunomodulation with FasL

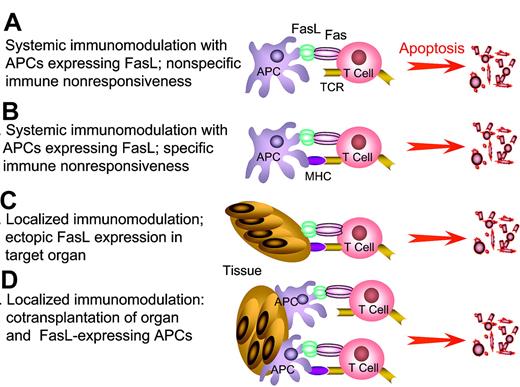

Systemic immunomodulation with cells genetically engineered to express FasL was shown to abrogate autoimmune6,9,11,45,48 and alloimmune responses.16,43,49 Presentation of auto or transplantation antigens in conjunction with FasL leads to the activation of T cells and expression of Fas. Subsequent engagement of Fas with FasL on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) results in apoptosis of T cells (Figure 3A-B). Elimination of key immune cells, such as CD4+ T lymphocytes, disrupts the chain of physiologic immune responses with potential therapeutic consequences.9,45 For example, dendritic cells genetically engineered to overexpress FasL transduce a death signal that results in immune nonresponsiveness to selected alloantigens and prolongs allograft survival.50,51 This immunomodulatory approach benefits from high specificity since only T cells responding to the presented antigens are targeted for elimination, while the remaining T-cell repertoire responsive to unrelated antigens is largely unaltered.48-52

FasL as an immunomodulatory approach to induce tolerance. APCs genetically modified to express FasL or “decorated” with exogenous FasL are injected into hosts with autoimmunity or allograft recipients to eliminate pathogenic, activated T cells by sheer physical close proximity (A) or antigen-mediated interaction (B). This approach has the potential to eliminate a significant repertoire of antigen-specific T cells, and as such generate systemic tolerance. Tolerance may be the end result of physical elimination of antigen-specific T cells and/or induction and expansion of T cells with regulatory functions. (C) Localized immunomodulation with FasL expressed in the target tissues. (D) Localized immunomodulation induced by cotransplantation of APCs expressing FasL with target tissues. The anticipation is that FasL in panels C-D will generate an immune-privileged site that provides the first line of defense and confers protection by keeping pathogenic T cells in check until long-lasting protective immunoregulatory mechanisms are activated. This approach is particularly attractive in transplant settings that allow the manipulation of donor graft, rather than the recipient for tolerance induction, and as such may be associated with minimal adverse side effects in the host compared with host systemic manipulation.

FasL as an immunomodulatory approach to induce tolerance. APCs genetically modified to express FasL or “decorated” with exogenous FasL are injected into hosts with autoimmunity or allograft recipients to eliminate pathogenic, activated T cells by sheer physical close proximity (A) or antigen-mediated interaction (B). This approach has the potential to eliminate a significant repertoire of antigen-specific T cells, and as such generate systemic tolerance. Tolerance may be the end result of physical elimination of antigen-specific T cells and/or induction and expansion of T cells with regulatory functions. (C) Localized immunomodulation with FasL expressed in the target tissues. (D) Localized immunomodulation induced by cotransplantation of APCs expressing FasL with target tissues. The anticipation is that FasL in panels C-D will generate an immune-privileged site that provides the first line of defense and confers protection by keeping pathogenic T cells in check until long-lasting protective immunoregulatory mechanisms are activated. This approach is particularly attractive in transplant settings that allow the manipulation of donor graft, rather than the recipient for tolerance induction, and as such may be associated with minimal adverse side effects in the host compared with host systemic manipulation.

Localized immunomodulation with FasL

Constitutive expression of Fas on selected cells of the body, such as hepatocytes, is associated with significant acute toxicity when agonistic anti-Fas antibodies are used for immunomodulation.53 To override this complication, a series of studies focused on localized expression of FasL in target tissues for immunotherapy (Figure 3C). An initial report showed excellent survival of pancreatic islet allografts cotransplanted with syngeneic myoblasts genetically engineered to express FasL to eliminate alloreactive lymphocytes by sheer physical proximity, rather than antigen-mediated interactions.54 These initial observations were followed by a series of studies using FasL as an immunomodulatory agent with variable results. While some studies reported extended survival of allogeneic grafts, such as liver, kidney, thyroid, pancreatic islets, lung, and cornea,55,56 others noted accelerated rejection of syngeneic and allogeneic grafts.57-59 A common denominator in the latter studies was the presence of massive inflammatory infiltrates, particularly neutrophils, in FasL-expressing tissues and organs, suggesting that rejection was initiated by a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction.

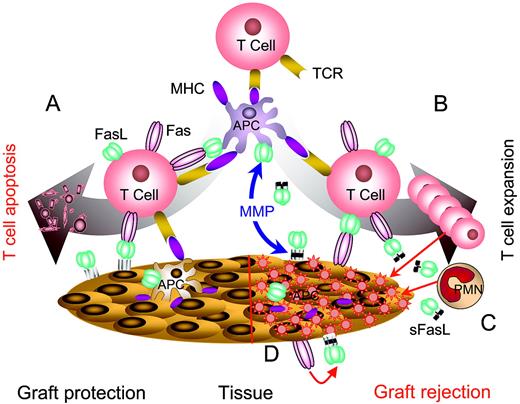

Plausible explanations for these contradictory observations include the use of wild-type FasL for immunomodulation, the nature of cells, tissues, and organs targeted for expression, and the ability of these systems to regulate FasL after translation. FasL accumulates as a soluble protein in the extracellular milieu following the cleavage of the membranous form by matrix metalloproteinases.34,35 Unlike the membranous form that effectively induces apoptosis in Fas-positive cells, sFasL may have either apoptotic or antiapoptotic attributes depending on the characteristics of the extracellular matrix. sFasL can induce apoptosis when it is anchored to the extracellular matrix to form oligomers (Figures 2, 4).36,40 In contrast, if sFasL is released in a milieu where the formation of oligomers is unattainable, it serves as an antiapoptotic factor by competing with the membranous form for binding to Fas.34 Thus, transduction of the apoptotic signal by membranous FasL is blocked in the presence of sFasL and the observed overall effect is inhibition of apoptosis.36,37,41,42 Furthermore, sFasL acts as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils (Figure 4), which may be responsible for the observed acute rejection of grafts in several studies where FasL is used as an immunomodulatory molecule.34,36,38,39 Consistent with this assertion are the acute rejection of allogeneic organs expressing wild-type FasL by T-cell–deficient RAG knock-out mice60 and failure of dendritic cells overexpressing FasL to elicit an immune reaction in animals depleted of granulocytes.51 The apoptotic activity associated with wild-type FasL in a given tissue is determined by the activity of metalloproteinases and the binding capacity of sFasL by the extracellular matrix. Therefore, tissues that facilitate the formation of the apoptotic form of FasL will benefit from the protective attributes of this molecule when used for immunomodulation, whereas tissues that promote the antiapoptotic and chemotactic functions of FasL will suffer from its destructive aspects.

Complexity of FasL-based immunomodulation. (A) Immunomodulation using noncleavable FasL expressed in target tissues or APCs. Noncleavable FasL is primarily apoptotic and effectively eliminates pathogenic T cells, resulting in the protection of target organs from autoimmunity and alloreactive immunity. (B) Wild-type FasL is cleaved from the surface of APCs or target tissues by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and accumulates in intercellular space. sFasL blocks apoptosis by competing for Fas binding with the membranous FasL and serves as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils (C). (D) Destruction of target tissues expressing Fas. Cells in selected tissues, such as myocytes, express Fas and are sensitive to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. Immunomodulation with APCs modified to express FasL or direct expression of FasL in such tissues results in tissue damage induced by the interaction of FasL with Fas.

Complexity of FasL-based immunomodulation. (A) Immunomodulation using noncleavable FasL expressed in target tissues or APCs. Noncleavable FasL is primarily apoptotic and effectively eliminates pathogenic T cells, resulting in the protection of target organs from autoimmunity and alloreactive immunity. (B) Wild-type FasL is cleaved from the surface of APCs or target tissues by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and accumulates in intercellular space. sFasL blocks apoptosis by competing for Fas binding with the membranous FasL and serves as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils (C). (D) Destruction of target tissues expressing Fas. Cells in selected tissues, such as myocytes, express Fas and are sensitive to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. Immunomodulation with APCs modified to express FasL or direct expression of FasL in such tissues results in tissue damage induced by the interaction of FasL with Fas.

In an effort to use FasL as an effective immunomodulator, several groups have generated mutant forms of FasL that lack the putative metalloproteinase cleavage site. These molecules were expected to exist strictly in membranous forms and as such possess only the apoptotic activity of FasL while lacking the antiapoptotic and chemotactic functions of the soluble molecule. The use of such molecules as tolerogenic agents, however, proved controversial. For example, Kang et al have generated a noncleavable FasL molecule by deleting the putative metalloproteinase cleavage site and found that ectopic expression of this molecule in pancreatic islets, as well as auxiliary cells, resulted in acute rejection.61 In contrast, Yolcu et al reported extended survival of allogeneic islets cotransplanted with allogeneic biotinylated splenocytes “decorated” with a metalloproteinase cleavage site–deficient FasL molecule chimeric with streptavidin (SA-FasL).43 The main functional differences between these modified molecules appeared to be their chemotactic effect on neutrophils. Islet allografts in the study of Kang et al were rejected secondary to neutrophilic infiltration, while Yolcu et al did not observe neutrophil infiltration into islet allografts.

Although it is a general consensus that membranous FasL is primarily apoptotic and sFasL antiapoptotic and chemotactic, these functional distinctions do not always apply. Several noncleavable, membranous derivatives of FasL were shown to induce inflammation.42,62 For example, tumors transfected with noncleavable forms of FasL initiated vigorous neutrophil-mediated inflammation and were completely rejected by syngeneic animals, whereas those expressing various soluble forms of FasL failed to trigger inflammation and grew progressively.42,62 The proinflammatory activity of membranous FasL may operate through the in situ death of the infiltrating neutrophils and release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β)63 or direct activation of monocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells to release chemotactic factors, such as IL-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1).64 In tumors, mouse sFasL was found to induce apoptosis.42 It is possible that some of the activities attributed to both membranous and soluble FasL were in fact caused by FasL released in microvesicles from tumors65 and T cells.66 sFasL may differentially interact with the stroma of tumors versus parenchymal tissues, and these interactions may dictate the function of FasL depending on whether it forms oligomers with apoptotic activity. Furthermore, species-specific differences in the behavior of membranous, vesicular, and soluble forms of FasL may contribute to the observed findings. It is well established that human sFasL is apoptotic, whereas the mouse sFasL lacks such activity, and membranous FasL's of both humans and mice are chemotactic for neutrophils.35,37,39,41-43,62

Advantages to FasL-mediated immunomodulation for tolerance induction

Cellular immunity involves a series of cell-to-cell contacts both among different cells of the immune system and between the pathogenic cells and the target tissues. The very nature of this interaction between immune cells and target tissues provides the conceptual basis for localized expression of FasL to achieve peripheral tolerance. There are several advantages to FasL-mediated immunomodulation. First, immune nonresponsiveness induced by tissues or cells expressing FasL has the potential to be antigen specific without major effect on the naive unstimulated T-cell repertoire,67 and as such preserves immunocompetence to unrelated antigens.10,43,50-52 Second, Fas/FasL-mediated immunomodulation primarily affects T helper 1 (Th1) destructive cells and spares immunoregulatory cells of both Th2 type and CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells (Tregs), which may in turn facilitate the development of peripheral tolerance.68,69 This notion is consistent with the observation that CD4+ T cells are important to FasL-mediated immunoregulation since the depletion of these cells abolishes the protection conferred by FasL.56 Particularly, naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ Tregs were recently found to be resistant to apoptosis, possibly owing to their expression of high levels of antiapoptotic genes.70 In transplantation settings, immunomodulation may not only prevent rejection, but also lead to central tolerance due to thymic selection of newly emerging T cells71,72 continuously exposed to circulating donor antigens.73 Third, effective elimination of pathogenic alloreactive T cells early following transplantation may curtail initial injury to the graft and further minimize the incidence and severity of chronic rejection, a pathogenic mechanism that is largely responsible for long-term graft failure in the clinic.74

Problems associated with tissue-specific expression of FasL for immunomodulation

Attempts to use ectopic expression of FasL to achieve peripheral tolerance have highlighted some of the difficulties faced by this approach. As with any procedure involving gene therapy, the introduction of genetic material into cells is controversial, has unpredictable consequences, and involves ethical considerations. Furthermore, clinical applications of gene therapy have been limited by low efficiency of available gene delivery systems, inability to control gene expression, and difficulties in targeting selected tissues.75 To circumvent some of these problems, the majority of experimental studies using FasL as an immunomodulatory agent were performed by ex vivo genetic manipulation of cells, tissues, or organs. There is mounting evidence pointing to the importance of controlled expression of ectopically introduced genes for therapeutic purposes, particularly those that are used for immunomodulation. Inasmuch as the immune response is a dynamic process that needs to be manipulated only at selected stages for a desired outcome, continuous and uncontrolled expression of therapeutic genes are neither necessary nor desirable as they may yield adverse effects. In the case of proteins with pleiotropic effects, such as FasL, the problem may be further accentuated since the target cells, tissues, and organs may lack the mechanisms needed for proper regulation of the proteins (Figure 4). For example, endothelial cells are resistant to FasL-mediated killing because they express high levels of antiapoptotic genes, such as FLIP, whereas myocytes are sensitive to FasL-mediated killing.76

The use of FasL as an immunomodulatory agent to induce peripheral tolerance invokes several considerations. The level of expression of FasL appears to be important to its therapeutic potential,56 and as such needs to be fine-tuned depending on the model system used and the tissue targeted for expression. High levels of FasL may have adverse effects on graft survival,77 particularly if the graft lacks mechanisms required for proper regulation of this molecule. Second, FasL exists in 3 different forms, each manifesting different functions.24-28 Therefore, the use of genetically modified forms of FasL having potent apoptotic functions with none or minimal inflammatory activities may be a critical consideration for its use as an immunomodulatory molecule to down-regulate immune responses. Diminished apoptotic function of membranous FasL following cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase testifies to the advantage of using noncleavable engineered FasL for immunomodulation.43,61 However, the use of genetically engineered FasL lacking the metalloproteinase cleavage site for immunomodulation resulted in conflicting observations.42,43,61,62,78 This controversy may be explained in light of a recent report demonstrating the existence of several putative metalloproteinase sites of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family.79 It is likely that some of the reported “noncleavable” forms may indeed possess unidentified metalloproteinase cleavage sites that facilitate the generation of sFasL with antiapoptotic and chemotactic functions. Third, the activity of FasL in various tissues is modulated by chemokines and cytokines and as such is responsible for both enhancement and reduction of its apoptotic effect.80 For example, cytokine and chemokine signaling cascades involving NF-κB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulate FasL expression, and Fas-mediated activation of caspases stimulates c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase to further up-regulate FasL expression.81 In addition, in rejected allografts the levels of FasL and TNF-α increase sharply, whereas in tolerated allografts these molecules are expressed at low levels.82 In contrast, TNF-α protects the liver from Fas-mediated apoptosis via a mechanism that involves up-regulation of Bcl-xL82 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) expression, both of which antagonize the apoptotic effect of FasL.26,83 Fas/FasL-mediated apoptotic cascade in hematopoietic cells is also inhibited by intracellular factors, such as FLICE/caspase-8–inhibitory protein (FLIP).84 Finally, the expression of FasL has to be sustained for a period of time sufficient for the elimination of the majority of alloreactive lymphocytes, including memory T cells that reside in nonlymphoid tissues and may be accessible to FasL-mediated killing only over an extended period of time.85

Various approaches have been explored to resolve the limitations associated with the use of FasL for immunomodulation. FasL has been transgenically expressed under the control of tissue-specific promoters.57,58 Direct injection of DNA encoding FasL into tissues affected by autoimmunity led to the elimination of autoreactive T cells and abrogation of autoimmune thyroiditis and arthritis.69 Alternatively, selected cells and tissues were genetically modified ex vivo and used as vehicles to carry the FasL molecule to target tissues. An excellent vehicle for this approach is the expression of FasL in APCs, in expectation of antigen-specific autoreactive and alloreactive T-cell elimination.50-52,86,87 In some cases, cotransplanted cells were used to deliver FasL to the site of the donor organ implant to confer peripheral defense.43,54 Of interest to the use of FasL as an immunomodulatory molecule is a recent approach that involves modification of biologic surfaces with biotin followed by decoration with FasL chimeric with core streptavidin.43,78 There are several advantages to this approach. First, the chimeric FasL protein forms tetramers and oligomers and as such has potent apoptotic activity. Second, the chimeric protein can be displayed on the surface of any cell, tissue, or organ in a rapid (∼ one hour) and effective (100% of the target) fashion. Third, the level of chimeric protein on the cell surface is easily adjustable for the desired effect. Fourth, the protein is transient with an in vivo half-life varying from 3.5 to 9 days depending on the target tissue. Therefore, the transient display of FasL may have advantage over its stable expression via gene therapy for immunomodulation to achieve tolerance due to pleiotropic functions of this molecule. The long-term persistence of FasL in vivo may cause undesirable side effects on the target tissue and even interfere with tolerance induction, via elimination of T regulatory cells upon repeated engagement with Fas expressed on these cells.70

Tissue-specific considerations: pancreatic islets

To understand the conflicting results reported by studies attempting to induce tolerance to pancreatic islets using FasL, it is important to analyze the role of Fas and FasL in the pathophysiology of type I diabetes (T1D). Several studies implicated the Fas/FasL interaction in the destruction of β cells and onset of T1D in animal models.88,89 Homozygous Fas-deficient nonobese diabetic (NOD)–lpr/lpr mice do not develop insulitis, whereas wild-type NOD and lpr heterozygote animals develop diabetes, suggesting that Fas-mediated cytotoxicity is crucial to the destruction of β cells.89 Under inflammatory conditions, β cells might express Fas and become sensitive to apoptosis induced by FasL expressed either on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells or under certain conditions on the islets themselves.88 Consistent with this contention was the observation that diabetes could not be induced in NOD-lpr/lpr mice by adoptive transfer of diabetogenic T cells.88 Also, development of insulitis at an accelerated tempo was observed in transgenic mice expressing FasL under the control of the insulin promoter,57,58 presumably due to T-cell–induced expression of Fas in β cells and their apoptosis via the autocrine loop.90 After the onset of insulitis, the inflammatory environment appears to perpetuate the islet sensitivity to FasL. For example, the proinflammatory chemokines IL-1β and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) induce the expression of Fas by pancreatic β cells, thus priming the islets to undergo apoptosis when in contact with reactive infiltrating lymphocytes.91 In corroboration of these experimental data, it was shown that β cells isolated from the pancreata of newly diagnosed T1D patients express high levels of Fas and are sensitive to FasL-mediated killing.91 In experimental transplant settings, islets genetically modified to express FasL were hyperacutely rejected by syngeneic hosts, indicating a detrimental effect of FasL on viability of the graft.57,58

In contrast to the aforementioned reports, a series of recent studies suggest that FasL is not toxic to pancreatic islets and plays a minor role in the pathophysiology of insulitis. Islet mortality did not increase when pancreatic islets were coincubated with membranous FasL, “decorated” with SA-FasL, or cultured in the presence of agonistic anti-Fas antibodies.43 Islets from young NOD mice became sensitive to FasL-mediated killing only when precultured with IL-1β and INF-γ to induce the expression of Fas.92 Furthermore, FasL was detected on the surface of α cells in diabetes-resistant and diabetes-prone mice, suggesting that FasL on the α cells might serve as a shield for the juxtaposed β cells.93 Because the treatment of NOD mice with anti-FasL antibodies did not prevent the accelerated diabetes mediated by adoptive transfer of diabetogenic T cells, it is likely that FasL was not a direct mediator of insulitis.94 Transplantation of neonatal pancreata from NOD-lpr/lpr mice, which lack Fas, into diabetic NOD mice resulted in islet graft rejection, suggesting that the rejection mechanism was Fas/FasL independent.94 The reported resistance of NOD-lpr/lpr to the development of diabetes by diabetogenic lymphocytes from NOD89 was attributed to a subset of T cells in the NOD-lpr/lpr mice that expresses high levels of FasL and presumably eliminates adoptively transferred lymphocytes expressing Fas.94,95 Finally, the expression of Fas was undetectable on β cells from young NOD mice, and present on only 1% to 5% of β cells from older animals.92 Taken together, these data indicate that the role of Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis in the destruction of β cells is complex and may depend on the animal model and experimental settings used.

The plausible role of Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis in the destruction of islets under pathogenic conditions further adds to the complexity of using FasL as an immunomodulatory molecule to curtail pathogenic auto and/or alloreactive reactions against islets. Rejection of genetically modified islets expressing FasL by neutrophil-mediated reactions57,58 versus prevention of islet allograft rejection by cotransplantation of allogeneic splenocytes decorated with a noncleavable isoform of FasL43 and syngeneic myoblasts genetically modified to express FasL54 are examples of just a few studies testifying to the intricate nature of FasL-based immunomodulation. Although immune mechanisms responsible for the protection of allogeneic islets in these models remain unknown, the lack of systemic tolerance was demonstrated by the rejection of a second set of islets transplanted under the contralateral kidney capsule.43,54 Thus, local immunomodulation with FasL may result only in clonal ignorance or in the induction of localized immune privilege.

Immunomodulation with FasL has the potential to prevent both allograft rejection and recurrence of autoimmunity. Such a robust effect may be feasible by systemic immunomodulation of the graft recipients with donor APCs expressing FasL followed by transplantation of islet allografts either genetically modified to express the membranous form of FasL or decorated with FasL to further achieve local protection. In light of recent evidence showing regeneration of pancreatic cells following the arrest of autoimmunity by various means,96 the administration of cytotoxic drugs that abolish tolerogenic mechanisms and the regeneration processes must be used cautiously. Furthermore, new therapeutic approaches using FasL must focus on immunomodulation without immunosuppression.

Endothelium of vascularized organ grafts

The beneficial and detrimental effects of FasL on the survival of vascularized allografts may depend on the isoform of FasL and the inherent sensitivity of the target organ to FasL-mediated apoptosis. Endothelial cells express low levels of FasL, resist FasL-mediated apoptosis, and are efficient in antigen presentation.55 Therefore, targeting these cells for the expression of FasL may hold great potential as an immunomodulatory approach to induce tolerance to vascularized allografts. Selective transgenic expression of FasL in endothelial cells was effective in preventing the development of intimal hyperplasia, transplant atherosclerosis, vasculopathy, and inflammatory cell infiltrates.97 Similarly, direct display of a non-cleavable form of FasL on the cardiac vascular endothelium resulted in significant prolongation of graft survival following transplantation into fully mismatched recipients.78 In contrast, transgenic expression of wild-type FasL under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter in cardiomyocytes resulted in accelerated rejection of heart grafts in syngeneic recipients, secondary to the infiltration of neutrophils.59 This was likely caused by the sensitivity of cardiac myocytes to Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis and the cleavage of membranous form into soluble molecule having neutrophil chemotactic function.64,76 Although it was shown that sFasL released under hypoxic conditions acts to limit apoptosis to endothelial cells,98 this beneficial effect may be compromised by the chemotactic function of this form of the molecule for neutrophils. It is, therefore, important to prevent the release of sFasL into the extracellular milieu to prevent injuries inflicted on the graft by nonspecific inflammatory infiltrates. Effective FasL-based immunomodulatory approaches for the induction of tolerance to cardiac grafts may require selective expression of a noncleavable form of FasL on the vascular endothelium for a period of time sufficient to eliminate the pool of alloreactive cells, provided that endothelial cells express all the donor antigens that provoke rejection. Otherwise, systemic immunomodulation of graft recipients with donor APCs manipulated to express FasL may be needed to induce effective tolerance.

Protection of kidney and liver allografts using FasL as an immunomodulatory molecule is also complex because selected cell types in these organs constitutively express Fas and as such are susceptible to FasL-mediated apoptosis.53,99 For example, systemic administration of agonistic anti-Fas antibodies have been associated with acute hepatic failure in mice.53 Despite this intrinsic sensitivity to FasL-mediated apoptosis, renal and liver allografts have been successfully protected by ectopic expression of FasL in these organs99 or treatment of graft recipients with donor cells expressing FasL, indicating that such an approach is well tolerated.43,86 However, direct ectopic expression of FasL in the liver resulted in opposing outcomes depending on the percentage of cells expressing this molecule.100 Expression of FasL in more than 11% of liver cells resulted in fulminant hepatitis, whereas lower expression was well tolerated. Importantly, transplantation of these livers into allogeneic recipients resulted in long-term graft survival.100 Low levels of FasL expression in hepatocytes do not necessarily induce apoptosis since they express a series of antiapoptotic molecules and survival factors, such as Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL,53 and metalloproteinases that cleave membranous FasL into soluble form having low or undetectable apoptotic activity.37 The liver also secretes hepatocyte growth factor that up-regulates the expression of Bcl-xL.101 In general, the liver is resistant to rejection and can also protect other organs from rejection when used for cotransplantation. For example, cotransplantation of the liver with pancreatic islet allografts leads to prolonged islet survival,102 owing to the ability of liver to serve as an active site for the deletion of alloreactive T cells.103 Although the precise nature of mechanisms mediating the deletion of alloreactive T cells is unknown, the presence of a CD4+ T-cell subset expressing FasL in the liver may provide an explanation.85 Therefore, the nature of target organs for FasL expression and the level and duration of expression in these organs are critical considerations for the effective use of FasL as an immunomodulatory agent.

Bone marrow cells

Expression of Fas and FasL by hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is variable and changes along lineage differentiation. Although a subpopulation of immature CD34+ CD38– human fetal liver cells was shown to express detectable levels of Fas,104 this molecule appears to transduce trophic rather than apoptotic signals in hematopoietic cells. It was demonstrated that FasL significantly promotes the viability of CD34+ CD38– cells in culture105 and enhances Fas-mediated stimulation of colony formation by CD34+ cells in response to a variety of cytokines, including sFasL.106 The physiologic expression of Fas in quiescent human CD34+ stem cells is relatively low, and as a consequence Fas-mediated apoptosis occurs at very low rates.104,107 After transplantation, allogeneic stem cells significantly increase their expression of Fas.108 However, CD34+ stem cells and early precursors of B cells and granulocytes are protected from apoptosis by increased levels of the antiapoptotic protein FLIP.84 Taken together, these data suggest that the most primitive stem cells are protected from Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis, and FasL under these conditions may transduce a stimulatory signal to stem cells before a shift in death responsiveness to Fas/FasL evolves during early differentiation.

FasL also appears to play a role in the “veto” phenomenon observed following bone marrow (BM) transplantation. Donor and host HSCs as well as host BM stroma up-regulate their expression of Fas in response to changes in cytokine milieu induced by transplantation.107,108 Factors shown to up-regulate Fas expression in culture include IFN-γ and TNF-α, which may be released in response to conditioning, the interaction between HSCs and the stroma, and the engraftment process.104,107 Interestingly, engraftment of the myeloid and erythroid lineages remains intact irrespective of donor T-cell–mediated perforin or FasL cytotoxic functions, suggesting that committed progenitors in the marrow are not as vulnerable to FasL and perforin-mediated killing as lymphoid progenitors.109 Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) induced in F1 hosts by the injection of parental splenocytes was associated with up-regulation of Fas on the host hematopoietic cells and their elimination via Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis without a major effect on donor hematopoietic cells, suggesting that Fas/FasL interactions regulate suppression of host stem cells.110 Beneficial effects of FasL on engraftment of HSCs have been demonstrated in experiments relying on ectopic expression of this molecule by gene transfer into quiescent lineage-negative BM cells using lentiviral vectors.86 Engraftment was also improved when FasL protein was expressed on the surface of BM cells (E.S.Y., N.A., and H.S., unpublished data). Although mechanisms of BM engraftment facilitated by FasL remain to be defined, these studies clearly demonstrate that immunomodulation by FasL is effective in preventing the rejection of cellular allografts.

In addition to the role of FasL in the engraftment of HSCs, it may also play a critical role in the induction of GVHD and associated lymphoid hypoplasia and B-cell dysfunction. Transplantation of T cells from FasL-deficient donors, but not perforingranzyme pathway–deficient donors, into lethally irradiated graft recipients in conjunction with T-cell–depleted marrow resulted in the lack of GVHD-associated lymphoid hypoplasia.109 While transplantation of FasL-positive T cells resulted in full chimerism, recipients of FasL-deficient donor T cells exhibited mixed chimerism, suggesting that FasL may play a critical role in the elimination of residual host hematopoietic cells remaining after irradiation.111 It is therefore not surprising that despite T-cell depletion, tolerance to allogeneic grafts could not be induced by means of hematopoietic chimerism using FasL-defective donor hematopoietic cells112 and in Fas-deficient recipients.113 The mechanisms of alloreactive cell depletion by FasL-expressing donor splenocytes and tolerance induction by hematopoietic chimerism are believed to differ, and remain unknown.114 A straightforward interpretation of the Fas/FasL interplay between the host and donor cells would suggest that the incidence and severity of GVHD might be increased in FasL-defective (gld) recipients, as indeed observed in transplant experiments.115 However, the development of GVHD is dependent on a functional Fas/FasL interaction in a more complex way. In the absence of functional FasL (gld) in donor CD4+ T cells116 and in Fas-deficient lpr recipients,117 the GVHD-associated morbidity and mortality were accentuated, arguing against a simple interaction between donor FasL and host Fas as a major pathophysiologic mechanism of GVHD. The potential use of FasL as an immunomodulatory agent to prevent GVHD remains to be explored.

Concluding remarks and future prospects

Apoptosis mediated by death receptors and ligands is critical to immune homeostasis and the establishment of self-tolerance. Particularly, Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis is central to AICD that regulates peripheral immune responses. This aspect of FasL has been extensively exploited for immunomodulation to curtail pathogenic immune reactions, such as those causing autoimmunity and allograft rejection. Irrespective of some reported difficulties, there is general agreement that FasL has the capacity to induce tolerance by eliminating auto and alloreactive cells in an antigen-specific manner. Selective immunomodulation holds great potential toward the development of effective therapies without the use of chronic immunosuppression. Nonspecific, systemic immunosuppressive therapy not only inflicts infections, secondary malignancies, and damage to selected organs, but also might block regenerative and tolerogenic processes. The extensive studies devoted to the use of FasL as a tolerogenic molecule highlight some advantages and difficulties associated with this system and provide insights into the physiologic mechanisms of action of this molecule. However, the use of FasL as an effective immunomodulatory approach will depend on careful consideration of several parameters, including the nature of cells and tissues that are targeted for the expression of FasL, the level and duration of expression, the use of apoptotic (membranous) versus antiapoptotic (soluble) forms of FasL, systemic versus localized expression, and the levels of chemokines, cytokines, and metalloproteinases in the extracellular milieu. The use of FasL as an effective immunomodulatory agent to induce tolerance will most likely require combined therapy with other immunomodulatory agents with synergistic functions to improve the therapeutic specificity, reliability, and efficacy.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 14, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2364.

Supported by grants from the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation (2003276 to N.A., I.Y., H.S., E.S.Y.), the Frankel Trust for Experimental Bone Marrow Transplantation (I.Y.), the Daniel M. Soref Charitable Trust (N.A.), the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (0120396B to E.S.Y.), the National Institutes of Health (R21 DK61333, R01 AI47864, and AI57903 to H.S., E.S.Y.), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (1-2001-328 to H.S.), a Kentucky State Lung Cancer Research grant, and the Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund (H.S.).

N.A. and H.S. contributed equally to this work.

We thank Dr C. Lacelle and D. Franke for critical reading of the manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal