Abstract

During ontogenesis and the entire adult life hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells have the capability to migrate. In comparison to the process of peripheral leukocyte migration in inflammatory responses, the molecular and cellular mechanisms governing the migration of these cells remain poorly understood. A common feature of migrating cells is that they need to become polarized before they migrate. Here we have investigated the issue of cell polarity of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in detail. We found that human CD34+ hematopoietic cells (1) acquire a polarized cell shape upon cultivation, with the formation of a leading edge at the front pole and a uropod at the rear pole; (2) exhibit an amoeboid movement, which is similar to the one described for migrating peripheral leukocytes; and (3) redistribute several lipid raft markers including cholesterol-binding protein prominin-1 (CD133) in specialized plasma membrane domains. Furthermore, polarization of CD34+ cells is stimulated by early acting cytokines and requires the activity of phosphoinositol-3-kinase as previously reported for peripheral leukocyte polarization. Together, our data reveal a strong correlation between polarization and migration of peripheral leukocytes and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and suggest that they are governed by similar mechanisms.

Introduction

During ontogenesis the earliest progenitors of the mammalian adult hematopoietic system are initially formed in the intraembryonic aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) and it seems very likely that such AGM-derived hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) emigrate and colonize the fetal liver, the main site of embryonic hematopoiesis. During neonatal stages, HSCs migrate again; they leave the fetal liver to enter the blood stream and home to the bone marrow (BM), the main side of adult hematopoiesis.1 More than 30 years of clinical experience as well as several animal models have demonstrated that neonatal and adult HSCs retain their ability to migrate into the BM and the capacity to reconstitute the entire hematopoietic system.2 It appears that the homing process of transplanted HSCs is based on a naturally occurring process in which adult HSCs and progenitors travel from BM to blood and back to functional niches in BM and maybe into other organs.3 Remarkably, despite the central role of these phenomena in hematopoietic stem cell biology and their therapeutic relevance, the molecular and cellular mechanisms, which involve chemokines for navigation, and adhesive proteins for interactions, to guide them to their appropriate niche, remain poorly understood.4-8

In contrast, more is known about the migration process of peripheral leukocytes in inflammatory responses in which they are attracted to leave the blood stream and enter tissues by crossing the vascular endothelium. As reviewed by Sanchez-Madrid and del Pozo,9 the first requirement for cells that initiate migration is the acquisition of a polarized morphology that enables them to turn intracellularly generated forces into net cell locomotion. In this context it has been shown that chemokines trigger processes that induce changes in the organization of the cytoskeleton, resulting in an observable switch from a spherical into a polarized cell shape. It is established that this polarization requires the activity of phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), an enzyme involved in signal transduction events.10,11 Polarized leukocytes form lamellipodia-like structures at the front side (ie, the leading edge) and contain a pseudopod-like projection at the rear pole called a uropod, a leukocyte-specific structure that plays an important role in cell motility and adhesion.9 These morphologic changes are accompanied not only by the redistribution of several intracellular but also transmembrane proteins (eg, chemokine receptors become localized at the leading edge while other intercellular cell adhesion molecules, including intercellular adhesion molecules [ICAMs], CD43, and CD44, concentrate at the uropod).9

In our current studies we have observed that human CD34+ cells acquire a polarized cell shape resembling the morphologic phenotype of migrating peripheral leukocytes when they are cultured ex vivo. Since the human CD34+ cell fraction is highly enriched for HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs),12 we wondered whether there are parallels between the polarization and migration processes of HSCs/HPCs and peripheral leukocytes. Here we have investigated this issue by immunochemistry and green fluorescent protein (GFP)–based approaches using a panel of uropod and leading-edge protein and lipid markers as well as the new hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell marker prominin-1/CD133 (human AC133 antigen)13-15 (for review see Bhatia16 and Corbeil et al17 ).

Materials and methods

Cell preparation and culture conditions

Umbilical cord blood (CB), BM, and peripheral blood (PB) of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–treated stem cell donors were obtained from unrelated donors after informed consent. Approval for BM and PB was obtained from the ethics commission of the Heinrich-Heine University, and approval for CB was obtained from the Paul-Ehrlich Institute. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Mononuclear cells were isolated from individual sources by Ficoll (Biocoll Separating Solution; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) density gradient centrifugation. Remaining red blood cells were lysed at 4° C in 0.83% ammonium chloride with 0.1% potassium hydrogen carbonate, followed by a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washing step. CD34+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell separation using the MidiMacs technique according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), yielding CD34+ cells of 65.5% ± 14.3% purity.

Freshly enriched CD34+ cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37° C and 5% CO2 at a density of approximately 1 × 105 cells/mL in serum-free (Stemspan H3000; Stemcell Technologies Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada) or serum-containing tissue culture medium (Myelocult H5100; Stemcell Technologies Inc) in the absence or presence of early acting cytokines (fetal liver tyrosine kinase 3 ligand [FLT3L], stem cell factor [SCF], thrombopoietin [TPO]; each at 10 ng/mL final concentration; PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ). To inhibit the PI3K activity of isolated cells we have added Ly294002 (Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany) at a final concentration of 50 μM to serum-free or serum-containing media supplemented with early acting cytokines.

Migration assays

Migratory potential of cultivated cells was analyzed by transmigration assays using 3-μm pore filters (Costar Transwell, 6.5-mm diameter; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY). CB-derived CD34+ cells were cultured for 2 days in Myelocult H5100 supplemented with early acting cytokines as described under “cell preparation and culture conditions.” The Transwell filters were washed with Myelocult H5100 before they were loaded with 100-μL cell suspension of cultivated cells. Afterward they were carefully transferred to another well containing 600 μL Myelocult H5100 supplemented with early acting cytokines and 100 ng/mL stromal cell–derived factor-1α (SDF-1α; R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN) and cultured overnight in a humidified atmosphere at 37° C and 5% CO2. To study the influence of PI3K activity on cell migration, the same assays were performed and Ly294002 was added at a final concentration of 100 μM to both to the top cell suspension and to the medium in the bottom chambers. The cultivation of the same amount of cells in 600 μL Myelocult H5100 supplemented with early acting cytokines and 100 ng/mL SDF-1α in the absence or presence of Ly294002 (100 μM) served as controls. Following overnight incubation, filters were carefully removed and the percentage of cells recovered in the bottom compartment was evaluated.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

CD34+ cells were generally cultured for 2 days in the presence of early acting cytokines in Myelocult H5100 medium before immunostaining. To conserve their polarized morphology, the CD34+ cells were prefixed for 5 minutes at room temperature with paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Taufkirchen, Germany) at a final concentration of 0.2% in the medium. Cells were then incubated with the AC133-phycoerythrin (PE) antibody (1:10; AC133/1; Miltenyi Biotec) diluted in PBS containing 10% donkey serum (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for at least 10 minutes at 4° C and postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at 4° C. Because PE is not a suitable fluorochrome for immunofluorescence microscopy, we counterstained the AC133-labeled cells with cyanin 3 (Cy3)–conjugated AffiniPure Fab fragment donkey antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:50; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories) diluted in PBS containing 10% donkey serum for at least 10 minutes at 4° C. Remaining mouse epitopes were saturated with unconjugated AffiniPure Fab fragment rabbit antimouse IgG (1:10; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories). Cells were divided in different aliquots and stained with one of the following primary mouse antibodies: anti-CD34–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; HPCA-2; BD PharMingen, Heidelberg, Germany), anti-CD43 (1G10; BD PharMingen), anti-CD44–FITC (J173; Immunotech, Marseille, France), anti-CD45–FITC (2D1; BD PharMingen), anti-CD50 (TU41; BD PharMingen), anti-CD54–FITC (84H10; Immunotech), anti-GM3 IgM (GMR6; Seikagaku America, East Falmouth, MA), or rat anti-CXCR4 (1D9; BD PharMingen). These antibodies were counter-stained using Cy2-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat antimouse IgG, donkey antimouse IgM, and goat antirat IgG + IgM; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories). Labeled cells were mounted in 75% glycerin containing propylgallat (50 mg/mL) and DAPI (4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole; 200 ng/mL; Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Cells were observed with an Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Goettingen, Germany) using a ×20 dry (Figure 2A-B) or a ×100 oil immersion objective (Figures 2Ci-2Dii, 3), respectively. In general, analyses of living cells were performed at 37° C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere using a DMIRB inverse fluorescence microscope equipped with a CO2 incubator chamber and a ×20 dry objective (Figures 1,4) (Leica, Bensheim, Germany). All pictures and videos were taken with an Axiocam digital camera and processed using Axiovision 3.1 Software (Carl Zeiss).

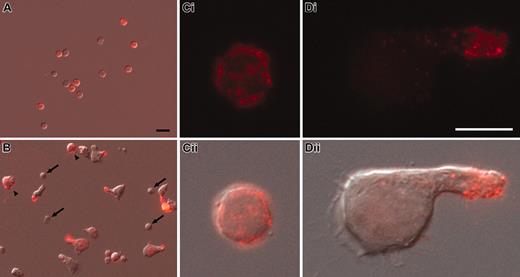

Cell surface redistribution of CD133 into the uropod of polarized CD34+ cells. (A-D) Human CD34+ cells, freshly isolated from umbilical cord blood (A,Ci-ii) or cultured for 2 days in the presence of early acting cytokines (B,Di-ii), were labeled with AC133 antibody (anti-CD133; red) and observed by immunofluorescence (Ci,Di). The overlays with the corresponding differential interference contrast images are shown (A-B,Cii,Dii). Note that the cultured CD133– cells remain small and round (arrows in B), whereas cultured CD133+ cells increase in size and CD133 becomes localized into the uropod of polarized cells (B,Di-ii) but remains distributed all over the surface of nonpolarized CD133+ cells (arrowheads in B). Same magnification was used in panels A and B (scale bar = 10 μm; A) or in panels Ci and Di (scale bar = 5 μm; Di), respectively.

Cell surface redistribution of CD133 into the uropod of polarized CD34+ cells. (A-D) Human CD34+ cells, freshly isolated from umbilical cord blood (A,Ci-ii) or cultured for 2 days in the presence of early acting cytokines (B,Di-ii), were labeled with AC133 antibody (anti-CD133; red) and observed by immunofluorescence (Ci,Di). The overlays with the corresponding differential interference contrast images are shown (A-B,Cii,Dii). Note that the cultured CD133– cells remain small and round (arrows in B), whereas cultured CD133+ cells increase in size and CD133 becomes localized into the uropod of polarized cells (B,Di-ii) but remains distributed all over the surface of nonpolarized CD133+ cells (arrowheads in B). Same magnification was used in panels A and B (scale bar = 10 μm; A) or in panels Ci and Di (scale bar = 5 μm; Di), respectively.

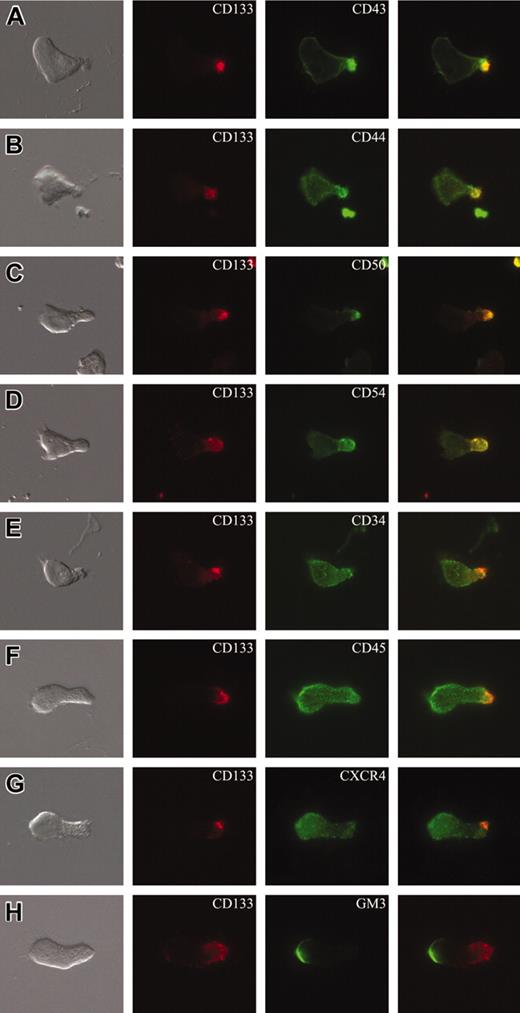

Cell surface distribution of plasma membrane markers in polarized CD34+ cells. (A-H) CD34+ cells isolated from umbilical cord blood and cultured for 2 days in serum-containing medium supplemented with early acting cytokines were subjected to double labeling using AC133 antibody (anti-CD133) and an antibody directed against another cell surface antigen, as indicated, and analyzed by double immunofluorescence. The CD133 immunofluorescence (red) is shown in the second column, the immunofluorescence of various cell surface antigens (green) in the third column, and the corresponding differential interference contrast image as well as the merge are shown in the first and the fourth column, respectively. Note that the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (G) and the ganglioside GM3 (H) are concentrated in the leading edge of the front pole, whereas CD43 (A), CD44 (B), ICAM3/CD50 (C), and ICAM1/CD54 (D) are enriched in the uropod of the polarized cells and colocalized with CD133. All panels are shown at the same magnification.

Cell surface distribution of plasma membrane markers in polarized CD34+ cells. (A-H) CD34+ cells isolated from umbilical cord blood and cultured for 2 days in serum-containing medium supplemented with early acting cytokines were subjected to double labeling using AC133 antibody (anti-CD133) and an antibody directed against another cell surface antigen, as indicated, and analyzed by double immunofluorescence. The CD133 immunofluorescence (red) is shown in the second column, the immunofluorescence of various cell surface antigens (green) in the third column, and the corresponding differential interference contrast image as well as the merge are shown in the first and the fourth column, respectively. Note that the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (G) and the ganglioside GM3 (H) are concentrated in the leading edge of the front pole, whereas CD43 (A), CD44 (B), ICAM3/CD50 (C), and ICAM1/CD54 (D) are enriched in the uropod of the polarized cells and colocalized with CD133. All panels are shown at the same magnification.

The human CD34+ cells acquire a morphologic polarity upon in vitro cultivation. (A-C) Light micrographs of human CD34+ cells freshly isolated from the umbilical cord blood (A) or cultured for 1 day (d1) in serum-free medium in the presence (B) or absence (C) of early acting cytokines as growth factors (GF). (D) The human CD34+ cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the presence of early acting cytokines and PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 (Ly). All panels are shown at the same magnification. Note, CD34+ cells that were cultured for 1 day in the presence of early acting cytokines (B) increase in size and acquire a polarized cell shape forming a leading edge at the front (arrowheads) and a uropod at the rear pole (arrows). Even in the absence of early acting cytokines, CD34+ cells can acquire a polarized cell shape, although they do not increase in size (C). The cell polarization and the growth process are inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor (D).

The human CD34+ cells acquire a morphologic polarity upon in vitro cultivation. (A-C) Light micrographs of human CD34+ cells freshly isolated from the umbilical cord blood (A) or cultured for 1 day (d1) in serum-free medium in the presence (B) or absence (C) of early acting cytokines as growth factors (GF). (D) The human CD34+ cells were cultured in serum-free medium in the presence of early acting cytokines and PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 (Ly). All panels are shown at the same magnification. Note, CD34+ cells that were cultured for 1 day in the presence of early acting cytokines (B) increase in size and acquire a polarized cell shape forming a leading edge at the front (arrowheads) and a uropod at the rear pole (arrows). Even in the absence of early acting cytokines, CD34+ cells can acquire a polarized cell shape, although they do not increase in size (C). The cell polarization and the growth process are inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor (D).

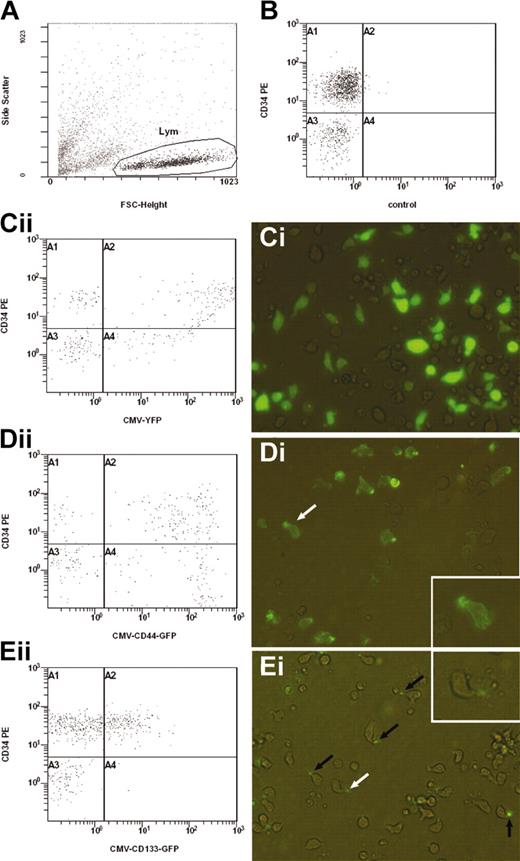

Subcellular localization of CD44-GFP and CD133-GFP fusion proteins in transfected CD34+ cells. Using the new Amaxa nucleofection technology, human CD34+ cells enriched from umbilical cord blood were transfected with the expression plasmid encoding either for YFP (Ci), CD44-GFP (Di-ii) or CD133-GFP (Ei-ii) under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Transfected cells and, as negative control, untransfected cells (B) were cultivated for 1 day in serum-containing medium supplemented with early acting cytokines and were analyzed by flow cytometry (A-B,Cii,Dii,Eii) and fluorescence microscopy (Ci,Di,Ei). (A-B,Cii,Dii,Eii) A representative experiment (n = 5) of the CB-derived cells untransfected (B) or transfected with different expression plasmids (Cii,Dii,Eii) was stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD34 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells analyzed in panels B, Cii, Dii, and Eii were gated according to the morphology depicted on a forward scatter/side scatter plot (A). Note, cells shown in panel Cii are extremely positive for YFP; most of them stick to the right border of the plot. (Ci,Di,Ei). Differential interference contrast image shows fluorescence overlay of YFP (Ci), CD44-GFP (Di), or CD133-GFP (Ei) in living transfected CD34+-enriched cells. The YFP is strongly expressed throughout the cytoplasm of the cells, whereas CD44-GFP and CD133-GFP are concentrated in the uropod of the migrating cells (arrows in Di and Ei). The white arrows indicate the cells shown in the insets (high magnification).

Subcellular localization of CD44-GFP and CD133-GFP fusion proteins in transfected CD34+ cells. Using the new Amaxa nucleofection technology, human CD34+ cells enriched from umbilical cord blood were transfected with the expression plasmid encoding either for YFP (Ci), CD44-GFP (Di-ii) or CD133-GFP (Ei-ii) under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Transfected cells and, as negative control, untransfected cells (B) were cultivated for 1 day in serum-containing medium supplemented with early acting cytokines and were analyzed by flow cytometry (A-B,Cii,Dii,Eii) and fluorescence microscopy (Ci,Di,Ei). (A-B,Cii,Dii,Eii) A representative experiment (n = 5) of the CB-derived cells untransfected (B) or transfected with different expression plasmids (Cii,Dii,Eii) was stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD34 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells analyzed in panels B, Cii, Dii, and Eii were gated according to the morphology depicted on a forward scatter/side scatter plot (A). Note, cells shown in panel Cii are extremely positive for YFP; most of them stick to the right border of the plot. (Ci,Di,Ei). Differential interference contrast image shows fluorescence overlay of YFP (Ci), CD44-GFP (Di), or CD133-GFP (Ei) in living transfected CD34+-enriched cells. The YFP is strongly expressed throughout the cytoplasm of the cells, whereas CD44-GFP and CD133-GFP are concentrated in the uropod of the migrating cells (arrows in Di and Ei). The white arrows indicate the cells shown in the insets (high magnification).

To analyze the degree of cell polarization, the living cells were photographed and their structure was evaluated. Cells with a commashaped morphology or with a recognizable tip (uropod) were determined as being polarized, whereas round and oval cells were determined as being nonpolarized. The percentage of viable cells was evaluated by trypan blue staining (0.4% solution; Sigma-Aldrich).

Plasmid construction and transfection of CD34+ cells

The eukaryotic expression vector plasmid enhanced GFP (pEGFP)–N1-CD133, containing the entire coding sequence of human CD133 fused in-frame to the N-terminus of GFP, was constructed by selective polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the corresponding cDNA (GenBank accession no. AF027208) using the oligonucleotides 5′-TTGGAGTTTCTCGAGCTATGGCCCTCGTACT-3′ and 5′-TTCAACATCAGCTCGAGATGTTGTGATGG-3′ as 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with XhoI and cloned into the corresponding site of pEGFP-N1 vector (BD Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany). The pEGFP-N1-CD44 plasmid encoding for human CD44 fused in-frame to the N-terminus of GFP was obtained by selective PCR amplification of the corresponding cDNA (GenBank accession no. AY101192) with the oligonucleotides 5′-CGCCTCGAGATCCTCCAGCTCCTTT-3′ and 5′-ATGGTGTAGAATTCGCACCCCAATC-3′ as 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with XhoI and EcoRI and cloned into the corresponding sites of pEGFP-N1 vector. In both constructs, GFP is fused in-frame to the cytosolic C-terminal domain of the CD marker and their expression is under control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter.

CB-derived CD34+ cells (1.5 × 105 to 3 × 105 cells) were transfected with 10 μg of plasmid DNA using the new Amaxa Nucleofection technology according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). As effectors we have used the pEGFP-N1-CD133 or pEGFP-N1-CD44 plasmids and, as a control, the plasmid yellow fluorescent protein–N1 (pEYFP-N1) or pEGFP-N1 vector, respectively. Following transfection, cells were immediately transferred into Myelocult H5100 supplemented with early acting cytokines. The efficiency of individual transfections was evaluated by staining the transfected cells 24 hours after the DNA incorporation with an anti-CD34–PE antibody (8G12; BD PharMingen) and analyzed by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy (see “Immunofluorescence and microscopy”).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a Cytomics FC 500 flow cytometer equipped with the RXP software (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany).

Results

Morphologic polarization of human CD34+ cells

Human CD34+ cells freshly isolated from different sources (CB, BM, and PB) are small (ie, 5-6 μm), round, and without any morphologic sign of cell polarity (Figure 1A). Remarkably, a high proportion of these cells increase in size and acquire a polarized cell shape when grown on uncoated plastic dishes in the presence of early acting cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3L; 10 ng/mL each) in either serum-supplemented or serum-free tissue culture medium (Table 1; Figure 1B). It should be mentioned that these early acting cytokines have been reported to preserve the multipotency and engraftment potential of human HSCs/HPCs in short-term cultures.18 Although the number of cells possessing a polarized shape is high and comparable between individual donor samples under serum-containing conditions, it is more variable under serum-free conditions (Table 1). Cells acquiring a polarized morphology form a leading-edge–like structure at one end and a uropod-like structure at the opposite side (Figure 1B, arrowheads and arrows, respectively). Even in the absence of any growth factor, some cells acquire a polarized cell shape in serum-containing or serum-free medium (Table 1), but they neither increase in size (Figure 1C) nor proliferate (data not shown). Although we did not add SDF-1 or any other chemokine, the cultivated cells were highly dynamic and exhibited an amoeboid movement that is very similar to the one described for migrating peripheral leukocytes9 (see the time-lapse videomicroscopy imaging in supplemented material). Additionally, we have observed that flow cytometrically sorted lin–CD34+CD38low/– cells as well as lin–CD34+CD38+ cells acquire a polarized cell shape upon cultivation in cytokine-containing media (data not shown).

Polarization and migration of CD34+ cells depend on PI3K activity

. | % polarized cells . | n . | % living cells . | n . | % migrated cells . | n . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture condition d0-d1; values d1 | ||||||

| Serum-free + GF | 64.90 ± 18.70 | 7 | 97.37 ± 1.84 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum-free | 37.75 ± 19.91 | 7 | 90.91 ± 1.91 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum-free + GF + Ly294002 | 3.91 ± 1.47 | 3 | 92.55 ± 1.11 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum + GF | 82.86 ± 5.84 | 7 | 96.74 ± 2.02 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum | 42.84 ± 25.61 | 3 | 83.53 ± 16.22 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum + GF + Ly294002 | 9.73 ± 3.20 | 3 | 91.05 ± 1.41 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Culture condition d2-d3; values d3 | ||||||

| Serum + GF + SDF-1α | 73.10 ± 3.85 | 3 | 94.48 ± 1.51 | 3 | 15.6 ± 4.20 | 3 |

| Serum + GF + SDF-1α + Ly294002 | 14.60 ± 7.12 | 3 | 87.39 ± 4.74 | 3 | 3.3 ± 0.25 | 3 |

. | % polarized cells . | n . | % living cells . | n . | % migrated cells . | n . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture condition d0-d1; values d1 | ||||||

| Serum-free + GF | 64.90 ± 18.70 | 7 | 97.37 ± 1.84 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum-free | 37.75 ± 19.91 | 7 | 90.91 ± 1.91 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum-free + GF + Ly294002 | 3.91 ± 1.47 | 3 | 92.55 ± 1.11 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum + GF | 82.86 ± 5.84 | 7 | 96.74 ± 2.02 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum | 42.84 ± 25.61 | 3 | 83.53 ± 16.22 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Serum + GF + Ly294002 | 9.73 ± 3.20 | 3 | 91.05 ± 1.41 | 3 | NE | 0 |

| Culture condition d2-d3; values d3 | ||||||

| Serum + GF + SDF-1α | 73.10 ± 3.85 | 3 | 94.48 ± 1.51 | 3 | 15.6 ± 4.20 | 3 |

| Serum + GF + SDF-1α + Ly294002 | 14.60 ± 7.12 | 3 | 87.39 ± 4.74 | 3 | 3.3 ± 0.25 | 3 |

Data are for CB-derived CD34+ cells; mean ± SD.

n indicates number of independent experiments; d0, freshly isolated cells; GF, growth factors (SCF, TPO, FLT3L); and NE, not estimated.

Polarization and migration of CD34+ cells depends on PI3K activity

When PI3K activity is inhibited by addition of Ly294002, peripheral leukocytes lose their polarized shape and round up.10 To investigate if PI3K activity is also required for the polarization of CD34+ cells we have cultured CB-derived CD34+ cells in early acting cytokine-supplemented media, in the presence or absence of Ly294002. While most of the CD34+ cells present in the control group acquired a polarized cell shape after 1 day (Table 1; Figure 1B), treated cells remained round (Table 1; Figure 1D) and viable (Table 1). Furthermore, when adding Ly294002 to polarized CD34+ cells cultured for 2 days in serum and early acting cytokine-containing medium, many of them lose their polarized morphology and round up but remain viable (Table 1). Taken together these data suggest that the PI3K pathway is involved in the polarization process of CD34+ cells.

Because cell polarity is an essential prerequisite for the migration process of several cell types,9 we have tested whether CD34+ cells that lose their polarized cell shape have a reduced migration capacity. Therefore, we have examined the migration rate of CB-derived CD34+ cells, which were originally cultured for 2 days in serum and early acting cytokine-containing medium, in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 using a transmigration assay. In the absence of Ly294002, 15.6% ± 4.20% of the CD34+ cells migrated through 3-μm pores of Transwell filters, whereas only 3.3% ± 0.25% of the cells treated with this PI3K inhibitor passed through the pores (Table 1).

The hematopoietic stem cell marker CD133 is redistributed to the uropod-like structure of migrating human CD34+ cells

A hallmark of the polarization of migrating peripheral leukocytes is an asymmetric redistribution of certain cell surface proteins into the well-defined architectural structures, the uropod and the leading edge.9 This prompted us to examine, by immunochemistry, the distribution of hematopoietic stem and progenitor marker CD133 in nonpolarized and polarized (ie, migrating) CD34+ cells. In our hands more than 90% of CD34+ cells isolated from CB, PB, or BM express CD133 (data not shown). Interestingly, we found that CD133, which is distributed over the entire cell surface of freshly isolated CB-derived CD34+ cells (Figure 2A,Ci-ii), is redistributed into the tip of the uropod-like structure in polarized CD34+ cells (Figure 2B,Di-ii). Under the same conditions, the cell surface redistribution of CD133 is not observed in nonpolarized cells (Figure 2B arrowhead). The same phenomenon is observed with CD34+ cells isolated from BM and PB (data not shown).

Segregation of several plasma membrane markers in polarized human CD34+ cells

Given the high similarity observed between the migrating CD34+ cells and peripheral leukocytes we decided to investigate the subcellular distribution of several membrane protein markers, including adhesion molecules and one membrane receptor, known to be enriched either in the uropod or at the leading edge of migrating peripheral leukocytes.9 Immunochemistry revealed that CD markers previously reported to be concentrated into the uropod of migrating peripheral leukocytes,9 including CD43, CD44, CD50 (ICAM3), and CD54 (ICAM1), are also enriched in the uropod-like structure of CB-derived CD34+ cells and colocalized with CD133 (Figure 3A-D). Similar data were obtained with PB-derived CD34+ cells (data not shown).

In contrast, we found that the CXCR4 chemokine receptor, which has been reported to be redistributed at the leading edge of B and T lymphocytes upon exposure to chemokines,19-21 appeared as a gradient with its highest expression in the leading edge of CD34+ cells (Figure 3G). Finally, the segregation of CD markers observed here is not a common characteristic shared by all of them since CD34 and CD45 are found equally distributed all over the surface of polarized CD34+ cells (Figure 3E and F, respectively).

Recently, it has been demonstrated that during polarization of T cells the monosi θ aloganglioside GM3, a raft-associated lipid, redistributes to the leading edge of activated leukocytes.22 To corroborate further the similarity underlying the polarization process between CD34+ cells and activated leukocytes, we analyzed the distribution of GM3 in CD34+ cells by immunochemistry. Remarkably, we found that GM3 is localized at the leading edge of polarized CD34+ cells (Figure 3H).

CD44-GFP and CD133-GFP fusion proteins are localized in the uropod of transfected human CD34+ cells

The morphologic data strongly suggest that certain plasma membrane markers are partitioned into specialized regions or domains of migrating human CD34+ cells. To rule out that the compartmentalization observed is generated by the use of antibodies creating an artificial cluster of a given membrane marker, we monitored the distribution of the protein markers CD44 and CD133 fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) in living CB-derived CD34+ cells. Under the specific and new nonviral transfection conditions described here (see “Plasmid construction and transfection of CD34 cells” in “Materials and methods”), up to 80% of CB transfected cells expressed the fluorescence protein reporter gene (Figure 4Cii quadrants A2 and A4), which is distributed into the entire cytoplasm (Figure 4Ci). No fluorescence is observed with untransfected cells (Figure 4B quadrants A2 and A4). Interestingly, fluorescence microscopy revealed that CD44-GFP fusion protein, which is expressed in more than 75% of transfected cells (Figure 4Dii quadrants A2 and A4), is associated with the entire plasma membrane being enriched in the uropod of the CB-derived cells (Figure 4Di). Likewise, CD133-GFP is selectively concentrated at the tip of the uropod of polarized CD34+ cells (Figure 4Ei), as previously observed by immunochemistry for the endogenous CD133 (Figures 2-3). It should be mentioned that in comparison to fluorescence protein alone and CD44-GFP, CD133-GFP is detected only in a specific subpopulation of CB-derived cells (ie, CD34+ cells; Figure 4Ei quadrant A2).

Discussion

Here we report 4 major observations. First, HSCs/HPCs acquire a polarized cell shape by a molecular mechanism dependent on the PI3K pathway. Second, polarized HSCs/HPCs exhibit an amoeboid movement, which is similar to the one described for migrating peripheral leukocytes. Third, the polarization of HSC/HPC plasma membrane leads to a redistribution of a particular set of markers from which several of them have been previously reported to be associated with lipid microdomains (lipid rafts). Fourth, the stem cell marker CD133 is selectively concentrated in the uropod of polarized HSCs/HPCs.

It is well established that HSCs/HPCs have the ability to migrate.1-3 Despite the evidence that SDF-1 triggers migration of HSCs/HPCs,4-8 the current knowledge of the mechanisms governing stem cell migration remains limited. For other cell types it has been shown that the acquisition of cell polarity is an essential prerequisite for the migration process.9 Although it has been noticed that some CD34+ cells acquire a polarized cell shape upon adhesion to fibronectin23 or when migrating under the influence of SDF-1 through a fibronectin-coated Transwell filter or a 3-dimensional meshwork of extracellular matrix components,5,24 the issue of cell polarity in HSCs/HPCs has not been analyzed in detail.

We were able to document that the CD34+ cells grown in suspension cultures in the presence of early acting cytokines acquire a polarized cell shape with a defined leading edge at the front pole and a uropod at the rear pole. This morphologic phenotype is highly related to the one described for polarized, migrating peripheral leukocytes. Since the polarization of peripheral leukocytes depends on the activity of chemokines,20,25,26 it is very suggestive that similar factors are not only involved in the migration process of HSCs but also required for the polarization of these cells. However, our data show that chemokines, including SDF-1, do not appear essential for the polarization of CD34+ cells. Moreover, although it is not known yet which factor triggers such polarization, we provide evidence that the activation of the PI3K pathway is crucial for this process, being consistent with results obtained for peripheral leukocytes.10,11 It is interesting to note that SCF, which was added to most of our cultures, has been reported to activate the PI3K signaling pathway similarly to SDF-1.10,11,27-29 SCF also has the capability to act as a chemoattractant for human HPCs,8 arguing that other factors than chemokines can induce polarization and migration of CD34+ cells. Finally, it is important to point out that the serum-free culture medium used in our assays contains insulin, which is another potential activator of the PI3K.30 Therefore, insulin might be responsible for the polarization of CD34+ cells under serum-free conditions in the absence of cytokines.

As mentioned in “Introduction,” the polarization process seems to be a prerequisite for cell migration. Indeed we show that CD34+ cells treated with a PI3K inhibitor lose not only their polarized morphology but also their ability to migrate, suggesting that polarization and migration are closely connected to each other in CD34+ cells, as they are in other cell types. The inhibition of these cellular processes may explain why the homing of CD34+ cells is disturbed when PI3K signaling is perturbed.31

In addition to the importance of the PI3K signaling, we have demonstrated that polarization of CD34+ cells is accompanied by the redistribution of certain transmembrane proteins. As in other leukocytes, CD43, CD44, CD50 (ICAM3), and CD54 (ICAM1) become concentrated into the uropod of CD34+ cells, whereas other molecules such as CD34 or CD45 remain distributed all over the plasma membrane.

The phenotypic similarity between polarized progenitor cells and other leukocytes is not restricted to their morphology and the distribution of uropod markers. We show that the chemokine receptor CXCR4, which is known to be enriched in the leading edge of migrating lymphocytes, is distributed in a gradient-like fashion with its maximal concentration in the leading edge of polarized CD34+ cells. In agreement with this finding, van Buul and colleagues32 have reported recently that a CXCR4-GFP fusion protein redistributes to the leading edge of the KG1a cells, an acute myeloid leukemia (AML)–derived cell line.

There is growing evidence that many membrane proteins are associated with certain lipids (eg, sphingolipid or cholesterol-based lipids). Such lipids are often clustered in special microdomains, in so-called lipid rafts.33 Depending on the lipids that form a special raft, lipid rafts traffic to certain plasma membrane domains (eg, the apical or basal plasma membrane). In this context they seem to function as platforms that are important to govern the subcellular distribution of associated membrane proteins.33 Indeed, it has been shown that polarization of peripheral leukocytes depends on the controlled redistribution of such specialized lipid rafts.22,34 In activated T cells for example, the monosialoganglioside GM3-enriched lipid rafts traffic to the leading edge, while others redistribute to the uropod pole, concentrating a specific set of membrane proteins, such as ICAM3, CD43, and CD44, there.22,34 The observation that these raft-associated markers are also concentrated at the uropod pole and GM3 at the leading edge of CD34+ cells further reinforces existing parallels in the polarization process of HSCs/HPCs with peripheral leukocytes and suggests that lipid rafts are also important for the polarization of HSCs/HPCs. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that cues and mechanisms underlying the polarization and migration of precursors and more mature hematopoietic cells appear common to all of them.

Interestingly, we found that the stem cell marker CD133, a cholesterol-binding protein,35 is also redistributed into the uropod of migrating CD34+ cells. Since CD133 is preferentially associated with plasma membrane protrusions in all cell types where it is expressed,35-38 and is incorporated into lipid rafts,35 it seems very likely that special lipid rafts organize the delivery and/or retention of CD133 in the uropod. As CD133 is selectively associated with microvilli and other plasma membrane protrusions within the apical plasma membrane in different epithelia of embryonic and adult tissues,37,38 it might be possible that epithelial cells and HSCs/HPCs use a similar mechanism to distribute CD133. In agreement with the postulation that the targeting and retention of proteins into a specialized plasma membrane domain of distinct cell types are mediated by a common intracellular machinery,39 the uropod of polarized HSCs/HPCs and therefore of other leukocytes would correspond to the apical domain of polarized epithelial cells.

In conclusion, our data show for the first time that the polarization and migration processes of CD34+ cells are highly related to those reported for migrating peripheral leukocytes. The comprehensive knowledge about these mechanisms in peripheral leukocyte biology should increase our understanding about HSC/HPC traffic during normal and malignant hematopoiesis and should help to improve the process of homing and engraftment of stem cells in clinical trials.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 1, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0511.

Supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SPP1109 GI 336/1-1, B.G. and P.W.; CO298/2-1, D.C.) as well as from the Forschungskommission of the Heinrich-Heine-Universität-Düsseldorf and the Stem Cell Network Nordrhein-Westfalen.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Michael Punzel for general discussion, comments on the manuscript, and providing us with PB and BM samples.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal