Comment on Lo-Coco et al, page 1995

In acute promyelocytic leukemia, single-agent caliceamicin-conjugated anti-CD33 (gemtuzumab ozogamicin) is very effective in re-inducing a complete molecular remission (CRm) in almost all patients in first or subsequent molecular relapse.

In this issue, Lo-Coco and colleagues report on using caliceamicin-conjugated anti-CD33 (gemtuzumab ozogamicin [GO]) to target and treat acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), favoring the concept1,2 that APL cells are very sensitive to GO, perhaps more so than other acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtypes. This was elegantly shown in patients in molecular relapse by reducing the number of copies of the APL-specific PML/RARα transcripts using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reinducing them into complete molecular remission (CRm).

Consequent to development of more sensitive methods to identify minimal residual disease, new definitions of remission and relapse have emerged for AML.3 For example, when a disease-specific gene rearrangement is known, it might be desirable to achieve the more profound CRm, such as a negative reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR). Conversely, in a molecular relapse the number of leukemia cells rises to a level detectable by RT-PCR, while the bone marrow is morphologically and cytogenetically normal and the patient is asymptomatic. A molecular relapse has special clinical significance in APL. Most APL patients in durable first CRm are cured; conversion to positive RT-PCR for PML/RARα almost uniformly predicts a clinical relapse within weeks or months.4,5 Thus, CRm has become the therapeutic goal in APL. This is not the case in all AML subtypes; for example, in AML with t(8;21), RT-PCR for the AML1/ETO transcript could remain positive while a patient is in complete remission for years.2

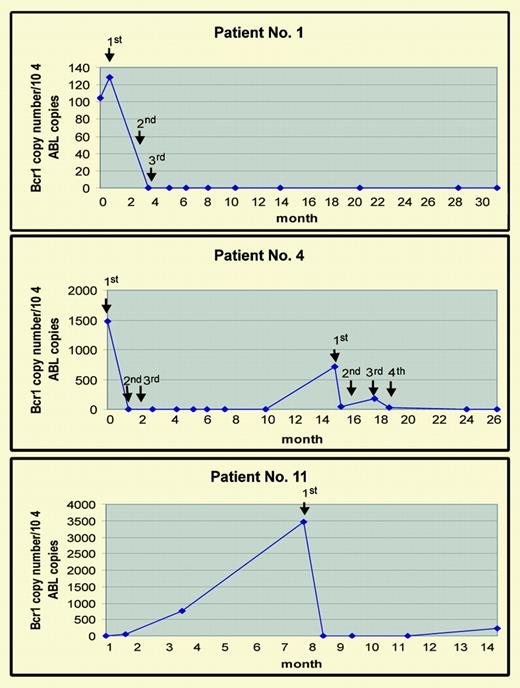

How should clinicians respond to this molecular information in APL? Should we treat a molecular relapse preemptively (as in this paper using GO) and in what way? There are 2 potential advantages to preemptive therapy. First, re-inducing CRm prevents the potentially fatal bleeding seen in APL if treatment is delayed until a clinical relapse. Second, treatment during minimal residual disease may result in a better long-term outcome than treating overt disease with greater disease burden. The paper clearly demonstrates that to the first question: GO is very effective in reinducing CRm in most patients in first or subsequent molecular relapse. Although 1 cycle of GO was effective in 6 of 7 patients, the minimum number of GO cycles is not clear, since most patients were not tested after the firstFIG1 cycle; however, 3 cycles seem to be sufficient. Other approaches acting by other mechanisms may also be effective, for example arsenic trioxide, which induces a very high CRm rate in overt APL relapse without the myelosuppression of GO.6 The second potential advantage is less clear. As opposed to first CRm, only 44% of the patients in this study remained in CRm, yet in comparison to their APL historic results of overt relapse, preemptive treatment provided a survival advantage. However, this could be explained, as the authors suggest, by preventing early death of overt relapse rather than lower disease burden. Thus, GO is probably not sufficient to maintain the remission. Additional therapy such as stem transplantation or other approaches is needed. Regardless, GO is a very active drug in APL and should be further studied in combination with other treatment modalities in this disease.

Results of Rt-Q-PCR studies from 3 patients during the therapy with GO. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 1995.

Results of Rt-Q-PCR studies from 3 patients during the therapy with GO. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 1995.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal