Abstract

Substantial evidence indicates that signaling through the CD40 receptor (CD40) is required for germinal center (GC) and memory B-cell formation. However, it is not fully understood at which stages of B-cell development the CD40 pathway is activated in vivo. To address this question, we induced CD40 signaling in human transformed GC B cells in vitro and identified a CD40 gene expression signature by DNA microarray analysis. This signature was then investigated in the gene expression profiles of normal B cells and found in pre- and post-GC B cells (naive and memory) but, surprisingly, not in GC B cells. This finding was validated in lymphoid tissues by showing that the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) transcription factors, which translocate to the nucleus upon CD40 stimulation, are retained in the cytoplasm in most GC B cells, indicating the absence of CD40 signaling. Nevertheless, a subset of centrocytes and B cells in the subepithelium showed nuclear staining of multiple NF-κB subunits, suggesting that a fraction of naive and memory B cells may be subject to CD40 signaling or to other signals that activate NF-κB. Together, these results show that GC expansion occurs in the absence of CD40 signaling, which may act only in the initial and final stages of the GC reaction. (Blood. 2004;104: 4088-4096)

Introduction

CD40 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily that was first identified and characterized in B cells.1-3 Signaling through the CD40 receptor was found to play an important role in multiple events in T-cell-dependent antibody responses, including B-cell survival and proliferation, germinal center (GC) and memory B-cell formation, and immunoglobulin (Ig) isotype switching.4

CD40 signaling occurs in B cells following interaction between the CD40 receptor on B cells and its ligand (CD40L) expressed mainly on activated CD4+ T cells. Patients carrying mutations in the CD40L gene develop a severe form of immunodeficiency, the hyper-IgM (HIGM) syndrome, characterized by elevated levels of IgM; low levels of IgA, IgG, and IgE; the absence of GCs; and the inability to mount T-cell-dependent humoral responses.5-8 CD40- or CD40L-deficient mice revealed a phenotype comparable to that of HIGM patients.9-11 These observations suggest that CD40 is required for T-cell-dependent immunoglobulin class switching and GC formation, but do not explain at which stage(s) of the GC reaction CD40 signaling is operative.

Several studies on CD40 activation of B cells in vitro have suggested a role of CD40 in all stages of mature B-cell physiology. CD40 activation is reportedly involved in proliferation, rescue from apoptosis, differentiation into GC B cells, isotype switching, and maturation into memory B cells, as well as prevention of differentiation of mature B cells into plasma cells.12-17 However, these in vitro studies cannot recapitulate the complexity of the GC reaction, and therefore, the results obtained may be dependent on the particular experimental context used.

CD40 signaling activates different mediators and pathways whose outcome is the regulation of transcription factors. The CD40 signal transduction pathway involves tyrosine kinases (including syk and lyn), serine/threonine kinases (stress-activated protein kinase/c-jun aminoterminal kinase [SAPK/JNK]; p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [p38 MAPK]; extracellular signal-regulated kinase [ERK]) and phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI-3) kinase.18,19 These different pathways lead to activation of transcription factors, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), NF of activated T cells (NF-ATs), and activator protein 1 (AP-1).20,21 Many of the CD40 effects depend on NF-κB activation, which can be considered the main downstream effector of CD40 signaling.20

Thus, the CD40-CD40L interaction has been extensively studied in the past years, and its critical role in B-cell responses has been established. Nonetheless, it is not yet understood at which stages of B-cell development signaling through CD40 occurs. In particular, neither in vivo genetic ablation nor in vitro B-cell stimulation experiments could determine whether CD40 signaling is active at the beginning of, throughout, or at the end of the GC reaction. To address this question, we first identified, using an in vitro system, the CD40 gene expression signature represented by genes that change expression after CD40 activation. This signature was used to investigate the presence of CD40 signaling in purified human B cells corresponding to defined developmental stages of the GC. The results were validated by examining NF-κB activation as well as the induction of CD40-induced genes as a readout of CD40 signaling in normal human lymphoid tissues by immunohistochemical analysis. The data indicate the absence of CD40 signaling in centroblasts (CBs) and in most centrocytes (CCs), while they suggest that it may be active in pre- and post-GC B cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and CD40 stimulation

The Epstein-Barr virus-negative (EBV-) Burkitt lymphoma cell line Ramos was transduced with a retroviral expression vector (PINCO) carrying cDNA coding for the enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP).22 NIH3T3 (murine CD40L [mCD40L]) and NIH3T3 (empty vector), kindly provided by Dr Hilda Ye (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), were cultivated in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Ramos (PINCO) cells were maintained in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech). Ramos (PINCO) cells were cocultivated with NIH3T3 (empty vector) or NIH3T3 (mCD40L) in a 2:1 ratio in 6-well plates at a cell density of 0.75 × 106/mL. BCR signaling was induced by adding 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) to Ramos (PINCO) cocultivated with NIH3T3 (empty vector). The plates were centrifuged at 290 rcf (centrifuge 5810R; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 5 minutes. After 24 hours, cocultivated cells were collected, and Ramos (PINCO) cells, following labeling with CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), were positively selected by magnetic cell separation using the MidiMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec). After magnetic cell separation, the purity of the bound (CD19+) fraction was checked by monitoring the EGFP expression on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Normal B-cell magnetic cell separation and flow cytometry

Tonsils were obtained from routine tonsillectomies performed at the Babies and Children's Hospital of Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center (New York, NY). Informed consent was obtained from the patients or was unnecessary because the material used was residual material following diagnosis, and data have been fully anonymized. Tissue collection was approved by the institutional ethical committee of Presbyterian Medical Center. The specimens were kept on ice immediately after surgical removal. Following mincing, tonsillar mononuclear cells (TMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Isopaque density centrifugation. The 4 B-cell subpopulations were isolated by magnetic cell separation by means of the MidiMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec); for details see Klein et al.23 Briefly, naive B cells were isolated by depletion of GC B cells (CD10, CD27), memory B cells (CD27), plasma cells/blasts (CD27), and T cells (CD3), followed by a positive enrichment of IgD+ cells. CBs were isolated in a single step by magnetically labeling CD77+ cells. To enrich for CCs, TMCs were first depleted for CBs (CD77); naive, memory, and plasma cells/blasts (CD39); and T cells (CD3). In a second step, CCs were enriched by CD10+ cells. Memory B cells were purified by depletion of GC B cells (CD10, CD38), plasma cells/blasts (CD38), and T cells (CD3), followed by a positive enrichment of CD27+ cells. The purity of the isolated fractions was determined on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), and by immunoglobulin variable (V) region gene analysis.23

Generation of gene expression profiles

Total RNA was extracted with the use of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and subsequently purified by RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Double-strand cDNA was generated from 5 μg total RNA by means of the SuperScript Choice System (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and a poly-dT oligonucleotide that contains a T7 RNA polymerase initiation site. The double-strand cDNA was used as template to generate biotinylated cRNA by in vitro transcription with the use of the MEGAscript T7 High Yield Transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) with biotin-11-cytidine triphosphate (biotin-11-CTP) and biotin-11-uridine 5′-triphosphate (biotin-11-UTP) (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The biotinylated cRNA was purified by means of the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) and fragmented according to the Affymetrix protocol (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Then, 15 μg fragmented cRNA was hybridized to U95Av2 microarrays (Affymetrix). The gene expression values were determined by the Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 software, using the Global Scaling option. The primary data are available through http://icg.cpmc.columbia.edu/faculty.htm.

Gene expression data analysis

To perform the supervised gene expression analysis we used the Genes@Work software platform, (downloadable from IBM Research),24 which is a gene expression analysis tool based on pattern discovery ideas.25-27

The dendrogram is generated by means of a hierarchical clustering algorithm based on the average-linkage method.28,29

Binary scoring approaches. In the following discussion, we will be using the logarithm of the average difference as a surrogate for the expression level.

Nomenclature. Given N1 samples of cell type C1 and N2 samples of cell type C2, we are interested in determining if the behavior of cell type C1 relative to C2 is consistent with the behavior of the unstimulated relative to the CD40-stimulated Ramos cells. This consistency is determined in terms of the set of genes that is differentially expressed in the unstimulated versus the CD40-stimulated Ramos cells. Let's denote by Gup (or Gdown) the set of Nup (or Ndown) genes that are up-regulated (or down-regulated) in unstimulated compared with the CD40-stimulated Ramos cells. The total set of differentially expressed genes in the untreated and treated Ramos cells will be denoted by Gtot(Gtot = Gup ∪ Gdown), whose number Ntot is equal to Nup + Ndown. We will say that a gene tracks the CD40 signal in C1/C2, if the difference in the average expression of that gene in C1 and C2 has the same sign as the difference in the average expression of that gene in unstimulated and stimulated Ramos cells. We will quantitatively assess the tracking of the CD40 signature by using 2 methods: the discrete binary score, and the continuous binary score. The former method measures the number of genes tracking the signature, whereas the latter measures the average extent to which the signature is tracked per gene.

Discrete binary scoring. In the discrete scoring method, we count the number νup (or νdown) of genes in set Gup (or Gdown) that track the CD40 signal in C1/C2. We also keep count of the total number νtot (equal to νup + νdown) of genes in set Gtot that track the CD40 signal in C1/C2. If the cell types C1 and C2 were independent of the CD40 signature (the null hypothesis), then each gene in Gtot would have a 0.5 probability of tracking the CD40 signature. In other words, in the null hypothesis, the sign of the difference in the expression average in C1 and C2 for each gene in Gtot would be equally likely to be the same as, or the opposite to, the sign of the difference in expression average for the same gene in the unstimulated versus the stimulated Ramos cells. The P value for νup, νdown, and νtot can be computed by means of a binomial test. For νtot, the corresponding P value is computed as

Continuous binary scoring. In the continuous scoring method, we measure the extent to which the genes that are up-regulated or down-regulated in the CD40 untreated cells as compared with the treated cells show the same differential expression trend in cells of type C1 when compared with cells of type C2. More precisely, let us define the normalized difference in the average expression between C1 and C2 for a given gene as

where

Under the null hypothesis, the quantities Sup, Sdown, and Stot will have zero mean and variance equal to 1/Nup, 1/Ndown and 1/Ntot, respectively. The minus sign in front of the sum over Gdown has no effect under the null hypothesis, but will make these scores positive if the corresponding genes showed a behavior in C1 and C2 that is predominantly consistent with the behavior of the CD40 unstimulated and stimulated cells. Under the null hypothesis, the continuous scores are the sum of independent and similarly distributed variables. Thus, we can invoke the central limit theorem (which can be applied given that both Nup and Ndown are large) and argue that these scores, when normalized by their standard deviations, are normally distributed. The P value for Sup, Sdown, and Stot can then be computed by means of a normality test. For Stot, the corresponding P value is computed as p = 1 - erf (√NtotStot), where erf(x) denotes the cumulative normal distribution, also known as the error function. Similar formulas hold for the computation of the P value for Sup or Sdown. If the actual numbers Sup,Sdown, and Stot are found to be very unlikely under the null hypothesis (low P values), then we can reject the null hypothesis and postulate that the pair C1/C2 track the CD40 signature for the corresponding set of genes.

Immunofluorescence

We performed c-Rel immunofluorescence as follows. First, 2- to 3-μm- thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tonsil sections were dewaxed and antigen retrieved in 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) as described before.30 Following blocking of nonspecific binding with 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)-buffered saline, pH 7.5, slides were incubated overnight with either affinity-purified rabbit anti-cRel antibody at 1 μg/mL (PC139; Oncogene Research Products, Darmstadt, Germany) or pooled nonspecific rabbit immunoglobulins (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The slides were then washed and incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA), followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-avidin (FITC-avidin) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or cyanin 3-avidin (Cy3-avidin) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). The sections were mounted and counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Molecular Probes). Mouse IgG1 antibodies against tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 (TRAF1) (sc-6253; clone H3) and JUNB (sc-8051; clone C-11) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and used at 1 μg/mL. For double immunofluorescent staining, JUNB mouse antibodies were counterstained with a goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor-488-conjugated antibody (Molecular Probes). Development in double immunohistochemistry was performed with a goat anti-mouse IgG1 AP-conjugated secondary antibody (Southern BiotechnologyAssociates) and nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (NBT-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl phosphate p-toluidine salt) color development (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) followed by the second immunostaining sequence with non-cross-reacting series of primary and secondary reagents and peroxidase development. Nuclear JUNB IgG1-stained sections were membrane stained with mouse IgG2a CD20 antibody (Dako-Cytomation), then counterstained with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (Southern Biotechnology Associates) and avidin-horseradish peroxidase (avidin-HRP) (Dako-Cytomation) and then developed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) (Sigma). Membrane TRAF1 IgG1-stained sections were nuclear-stained with rabbit Ki-67 antibody (Dako-Cytomation), and then counterstained with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Southern Biotechnology Associates) and avidin-HRP (Dako-Cytomation) and developed with AEC. The images were acquired as monochromatic jpeg files by means of a Spot2 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) mounted on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and linked to a G4 Apple computer (Apple Computers, Cupertino, CA). The monochromatic images were merged in 3-color images with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Pictures were acquired using magnifications of 10 × /0.25 and 40 × /0.95.

Results

CD40-induced gene expression signature

CD40 signaling was induced in a human Burkitt lymphoma cell line (Ramos; EBV-) by cocultivation with fibroblasts that were stably transfected to express CD40 ligand, or with control fibroblasts. Burkitt lymphoma cells represent the transformed counterpart of GC CBs. Since primary CBs cannot easily be manipulated in vitro, we chose transformed CBs (instead of naive B cells) as more representative of the cell targets to be analyzed. After 24 hours of cocultivation, B cells were purified from fibroblasts by magnetic cell separation. To ensure that the procedure was effective in activating CD40 signaling, the change in expression of the known CD40-responsive genes bfl-1 and BCL-6 was verified by Northern Blot analysis, which confirmed the up-regulation of bfl-1 and the down-regulation of BCL-6 (data not shown).31-33 Flow cytometric analysis confirmed the expected induction of cell surface expression of CD95/fatty acid synthase (FAS) and CD80/B7.1 (data not shown).34,35 Total RNA was isolated from CD40-stimulated and unstimulated (cultivated with fibroblasts not expressing CD40 ligand) Ramos cells from 6 independent experiments, and labeled cRNAs were generated and hybridized to Affymetrix U95Av2 Gene Chips containing oligonucleotides corresponding to approximately 12 000 genes. The gene expression data were analyzed by the Genes@Work software platform.24-27 Genes differentially expressed in the 2 groups of CD40-stimulated and unstimulated samples were identified by supervised analysis using highly stringent criteria (requiring consistency in the expression values across at least 5 of 6 samples in each group).

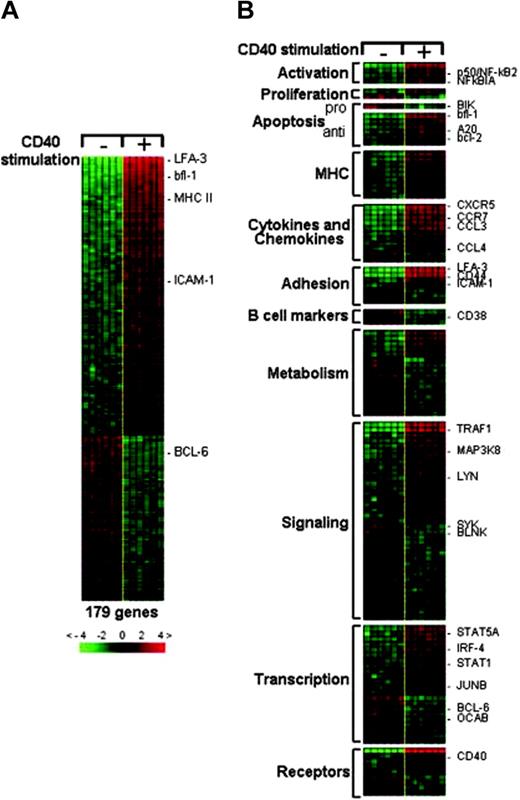

The resulting CD40 gene expression signature comprised 106 up-regulated and 73 down-regulated genes (Figure 1A). To investigate the specificity of the genes identified after CD40 stimulation, we analyzed the expression of the CD40 signature genes in the same cell system upon induction of BCR signaling (see Figure S1, available on the Blood website; click the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Only about 7% of the genes were consistently affected by both the stimuli, suggesting that the CD40 signature genes do not resemble a general “activation” signature that can be generated through another B-cell-activating signal. The CD40 signature genes were assigned to putative functional categories to enable us to better interpret the functional effects of the CD40 signaling (Figure 1B). Consistent with the known role of CD40 signaling in preventing apoptosis of B cells in vitro, the signature contained several genes involved in apoptosis: almost all were antiapoptotic genes and were up-regulated; BIK, a proapoptotic gene, present in the signature, was down-regulated, thus confirming the establishment of an antiapoptotic program. As expected, many transcripts encoding major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II as well as adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule-1 [ICAM-1], lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3 [LFA-3]) were induced, consistent with the involvement of these genes in T-cell-B-cell interactions.36,37 Several chemokines (CC chemokine ligand 3 [CCL3], CCL4, CCL22) that function in attracting T cells, as well as chemokine receptors involved in B-cell homing in secondary lymphoid tissue (CXC chemokine receptor 5 [CXCR5], CC chemokine receptor 7 [CCR7]), showed increased expression.38,39 Lymphotoxin-α and lymphotoxin-β, which play a role in dendritic cell recruitment and GC formation, were up-regulated.40,41 The CD40 receptor gene, as well as the genes coding for proteins involved in CD40 signal transduction (TRAF1, PI-3 kinase, Lyn tyrosine kinase, and p50), were also induced. Overall, the most prominent aspects of the identified CD40 signature were the up-regulation of antiapoptotic and adhesion-related genes.

Generation of the CD40 gene expression signature. Six samples of each type of CD40-stimulated and unstimulated Ramos cells were studied by DNA microarray analysis. Genes differentially expressed in the 2 groups were identified by supervised analysis by means of the Genes@Work software platform. In the matrix, columns represent samples and rows correspond to genes. Red and green indicate up-regulated and down-regulated expression, respectively. Values are quantified by the scale bar, which visualizes the difference in the ζ-score (expression difference/standard deviation) relative to the mean. Genes are ranked based on the z score (mean expression difference of the respective gene in phenotype and control group/standard deviation). (A) The CD40 gene expression signature comprised 106 up-regulated and 73 down-regulated genes. Some of the genes whose expression is known to change upon CD40 activation are indicated. (B) A subset of the CD40 signature genes is shown according to their distribution in functional categories. For the complete list of genes, including GenBank Accession numbers and Affymetrix codes, see Table S1, available on the Blood website (click the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Generation of the CD40 gene expression signature. Six samples of each type of CD40-stimulated and unstimulated Ramos cells were studied by DNA microarray analysis. Genes differentially expressed in the 2 groups were identified by supervised analysis by means of the Genes@Work software platform. In the matrix, columns represent samples and rows correspond to genes. Red and green indicate up-regulated and down-regulated expression, respectively. Values are quantified by the scale bar, which visualizes the difference in the ζ-score (expression difference/standard deviation) relative to the mean. Genes are ranked based on the z score (mean expression difference of the respective gene in phenotype and control group/standard deviation). (A) The CD40 gene expression signature comprised 106 up-regulated and 73 down-regulated genes. Some of the genes whose expression is known to change upon CD40 activation are indicated. (B) A subset of the CD40 signature genes is shown according to their distribution in functional categories. For the complete list of genes, including GenBank Accession numbers and Affymetrix codes, see Table S1, available on the Blood website (click the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

The activation of the NF-κB transcription factors is a main downstream effect of CD40 signaling. Consistently, the CD40 signature included numerous genes that were previously reported to be NF-κB dependent: genes involved in apoptosis (A20, bfl-1, IEX-1, FLIP, bcl-2),32,42-44 cell adhesion (ICAM-1),45 cytokines (IL-1beta, TNF-alpha, TNF-beta, CCL3, CCL4, CXCR5),46-53 and signaling (TRAF1).54 Thus NF-κB emerged once more as a critical mediator of CD40 signaling in our system.

Tracking CD40 signaling in purified normal B-cell subpopulations

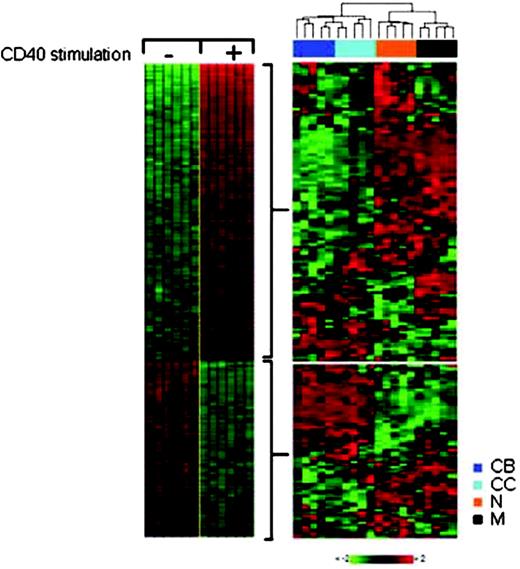

To investigate the activity of CD40 in normal B cells, we interrogated for the presence of the CD40 signature in the gene expression profiles generated from pre-GC naive B cells (IgD+, CD38low, CD27-, CD10-, CD3-, and CD14-); GC B-cell populations (centroblasts, CD77+ and CD38high; centrocytes, CD10+, CD38high, CD77-, CD39-, and CD3-); and post-GC memory B cells (CD27+, CD38low, CD10-, CD3-, and CD14-) purified from human tonsils.23 Details on the purification and gene expression profile analysis of these subpopulations were previously reported.23 The expression of the CD40 signature genes identified in Figure 1 was analyzed in the normal subpopulations by unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Figure 2 shows that the GC and non-GC (naive and memory) B cells readily separated into 2 subgroups, indicating a significantly different pattern of expression of CD40 signature genes. Interestingly, the majority (greater than 70%) of CD40 up-regulated genes on average showed a higher expression in naive and memory B cells than in GC B cells, and the majority (at least 70%) of CD40 down-regulated genes on average showed a lower expression in naive and memory B cells, suggesting the presence of the CD40 signature in these 2 cell types. To quantify the relatedness of any of the individual subpopulation pairs to the CD40 signature, we followed an approach (named binary scoring) that allowed us to determine whether the expression of a gene in a given cell pair (eg, GC versus naive B cells) is consistent with that observed in CD40-unstimulated versus CD40-stimulated cells. The approach was implemented in 2 complementary ways: a discrete score that measures the number of consistent genes, and a continuous approach that measures the average expression difference in the pairs (see “Materials and methods” for the precise definitions). The output of these binary scoring approaches is a significance level that estimates how unlikely it is that the observed consistency occurs merely by chance. Both the discrete and continuous scores demonstrated the presence of the CD40 signature in memory and naive B cells at high significance when compared with GC B cells (P ≤ 10-7). These results suggest that CD40 signaling is not activated in the bulk of the GC B cells, while naive and memory B cells (or subsets of them; see following section) are subjected to CD40 stimulation and/or other signals that can induce a similar pattern of gene expression.

Tracking the CD40 signature in normal B cells. The CD40 gene expression signature (left panel) was used to track the activity of CD40 signaling in normal B cells with the use of the gene expression profiles of pre-GC naive B cells (N), GC B-cell populations (CB and CC), and post-GC memory B cells (M). The expression of the CD40 signature genes in the normal B-cell subpopulations was analyzed by hierarchical clustering with the use of the average linkage method (right panel). The color scale identifies relative gene expression changes normalized by the standard deviation, with 0 representing the mean expression level of a given gene across the panel. The first branching in the dendrogram separates the GC (CB and CC) from the non-GC (N and M) B cells. The majority of the 106 CD40 up-regulated genes showed higher expression in naive and memory B cells compared with CBs and CCs. Reciprocal gene expression patterns were observed for the CD40 down-regulated genes that are mostly expressed at lower levels in naive and memory B cells compared with GC B cells. The expression of the CD40 signature genes in CBs and CCs mimics the expression of those genes in unstimulated cells, suggesting that CD40 signaling is not active in GC B cells. To further quantify the presence of the CD40 signature, we used 2 binary scoring approaches (see “Materials and methods”), showing that the CD40 signature of stimulated cells was absent from GC B cells and detectable in naive and memory B cells at P ≤ 10-7.

Tracking the CD40 signature in normal B cells. The CD40 gene expression signature (left panel) was used to track the activity of CD40 signaling in normal B cells with the use of the gene expression profiles of pre-GC naive B cells (N), GC B-cell populations (CB and CC), and post-GC memory B cells (M). The expression of the CD40 signature genes in the normal B-cell subpopulations was analyzed by hierarchical clustering with the use of the average linkage method (right panel). The color scale identifies relative gene expression changes normalized by the standard deviation, with 0 representing the mean expression level of a given gene across the panel. The first branching in the dendrogram separates the GC (CB and CC) from the non-GC (N and M) B cells. The majority of the 106 CD40 up-regulated genes showed higher expression in naive and memory B cells compared with CBs and CCs. Reciprocal gene expression patterns were observed for the CD40 down-regulated genes that are mostly expressed at lower levels in naive and memory B cells compared with GC B cells. The expression of the CD40 signature genes in CBs and CCs mimics the expression of those genes in unstimulated cells, suggesting that CD40 signaling is not active in GC B cells. To further quantify the presence of the CD40 signature, we used 2 binary scoring approaches (see “Materials and methods”), showing that the CD40 signature of stimulated cells was absent from GC B cells and detectable in naive and memory B cells at P ≤ 10-7.

Validation in normal lymphoid tissues

To validate the gene expression profiling results in vivo, we investigated the status of NF-κB activation as a measure of CD40 signaling in normal human lymphoid tissues by immunohistochemical analysis. Cytoplasmic NF-κB molecules would imply inactivity of NF-κB and thus absence of CD40 signaling, while nuclear NF-κB would imply activation of NF-κB by CD40 or other signals.

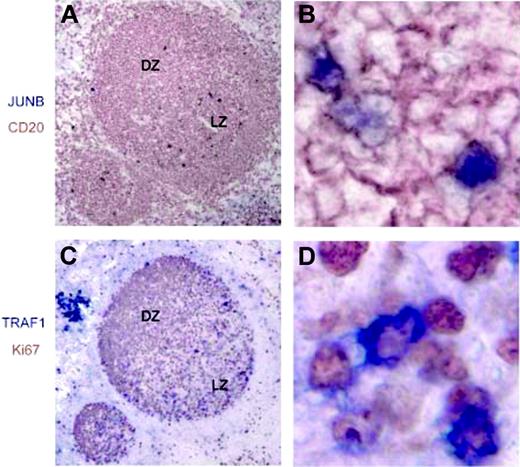

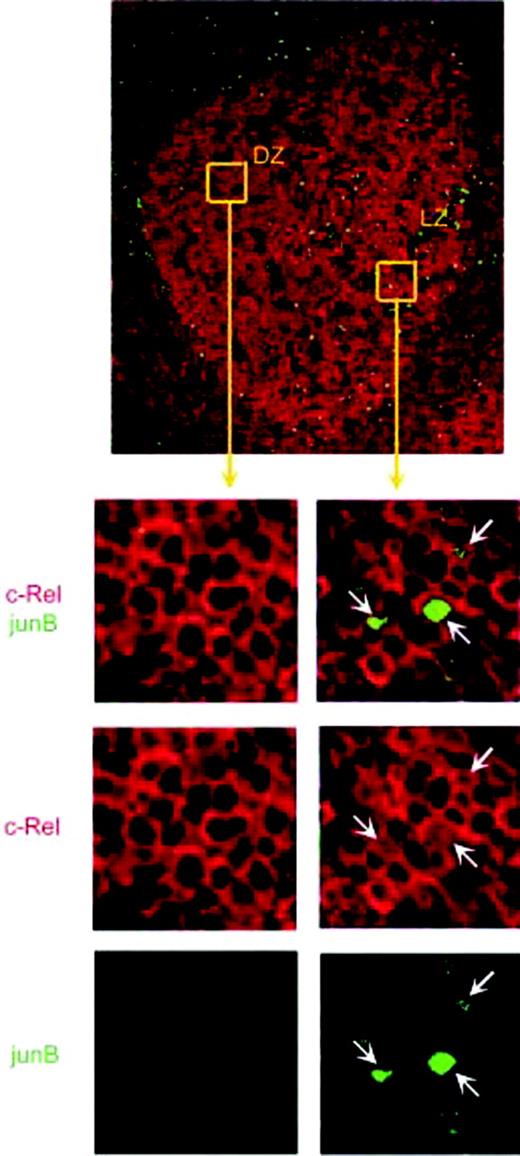

We examined the subcellular localization of the c-Rel (Figure 3) and p65 (data not shown) NF-κB subunits, which are known to be expressed in mature B cells.55 In the majority of GC B cells, notably in all CBs in the dark zone, NF-κB was found to localize in the cytoplasm, indicating the absence of CD40 signaling. A predominant cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB was also found in cells of the mantle zone, although nuclear NF-κB was detectable in rare cells. Conversely, nuclear staining for c-Rel was detectable in a subset of CCs in the GC light zone. Nuclear NF-κB was also present in a fraction of cells in the tonsillar subepithelium and in the tonsillar marginal zone equivalent, where most memory B cells are thought to localize.56 We performed the analysis on at least 5 GCs on each of 7 tonsils, obtaining absolutely consistent results. Coimmunostainings were performed for CD20 and the c-Rel or p65 NF-κB subunits on tonsillar sections, confirming the distribution of nuclear NF-κB in a subset of B cells in the light zone and in the subepithelium (data not shown). Moreover, we performed immunostainings for TRAF1 and JUNB that were identified among the genes induced by CD40 signaling. Both proteins were absent in the GC dark zone, while several positive cells were detected in the light zone, mimicking the distribution of the nuclear c-Rel+ cells (Figure 4). Coimmunostaining for c-Rel and JUNB confirmed JUNB expression in centrocytes displaying NF-κB activation (Figure 5). JUNB can be also expressed by T cells; however, the staining with CD20 (Figure 4) and CD3 (data not shown) showed that the majority of JUNB-expressing cells in the light zone are B cells. Interestingly, the JUNB+ B cells localize close to CD3+ T cells, consistent with the requirement of B-cell/T-cell interaction for the delivery of CD40 signaling. Together, these results are consistent with the gene expression data that indicated the absence of CD40 signaling in most GC B cells. Accordingly, the presence of nuclear NF-κB in a subset of cells in the mantle zone, marginal zone, and subepithelium is consistent with the activity of CD40 in a subset of naive and memory B cells, which are located in these regions. However, an estimation of the actual percentages of cells showing nuclear NF-κB among the naive and memory B cells is impossible as the cells are scattered over different compartments in the lymphoid tissue (T-zone, marginal zone equivalent, subepithelium). In addition, the fact that IgM+IgD+ B cells, which constitute a large fraction of tonsillar B cells, might represent either naive or memory B cells would further complicate an estimation of the respective fractions that receive CD40 stimulation. Finally, although the purified CC subpopulation is likely to contain the GC cells showing activation of NF-κB, we previously observed that this fraction, which was sorted on the basis of the absence of the CD77 antigen, is rather heterogeneous and its gene expression profile strongly resembles that of the CB fraction.23

Subcellular distribution of NF-κB in normal B cells. The main effectors of CD40 signaling are NF-κB transcription factors that translocate to the nucleus upon CD40 stimulation. Immunofluorescence was performed for the c-Rel NF-κB subunit on tonsillar sections to identify the cytoplasmic or nuclear localization of NF-κB in normal lymphoid tissues. The upper panel shows a tonsillar GC (magnification 10×). Dark zone (DZ), light zone (LZ), and the equivalent of the marginal zone in tonsil (“MZ”) are indicated. Green represents c-Rel; red, the nuclear counterstaining. The lower panels shows the 3 indicated GC regions at higher magnification (40 ×). In most GC B cells, NF-κB localizes in the cytoplasm: only a subset of CCs in the LZ shows nuclear staining for c-Rel (yellow arrows). Nuclear NF-κB is present in a fraction of cells in the tonsillar equivalent of the MZ that is populated mostly by memory B cells.

Subcellular distribution of NF-κB in normal B cells. The main effectors of CD40 signaling are NF-κB transcription factors that translocate to the nucleus upon CD40 stimulation. Immunofluorescence was performed for the c-Rel NF-κB subunit on tonsillar sections to identify the cytoplasmic or nuclear localization of NF-κB in normal lymphoid tissues. The upper panel shows a tonsillar GC (magnification 10×). Dark zone (DZ), light zone (LZ), and the equivalent of the marginal zone in tonsil (“MZ”) are indicated. Green represents c-Rel; red, the nuclear counterstaining. The lower panels shows the 3 indicated GC regions at higher magnification (40 ×). In most GC B cells, NF-κB localizes in the cytoplasm: only a subset of CCs in the LZ shows nuclear staining for c-Rel (yellow arrows). Nuclear NF-κB is present in a fraction of cells in the tonsillar equivalent of the MZ that is populated mostly by memory B cells.

JUNB and TRAF1 expression in normal lymphoid tissues. Serial sections of tonsillar GC were stained with JUNB, CD20, TRAF1, and Ki67 (A,C; magnification 10×). The right panels are enlargements from the light zone (magnification 80×). (A,B) Cells displaying nuclear staining for JUNB (blue) localize in the light zone (LZ) and show costaining for CD20 (brown). (C,D) Ki67 staining (brown) identifies the GC DZ (Ki67high) and LZ. GC cells expressing cytoplasmic TRAF1 (blue) are located mainly in the light zone.

JUNB and TRAF1 expression in normal lymphoid tissues. Serial sections of tonsillar GC were stained with JUNB, CD20, TRAF1, and Ki67 (A,C; magnification 10×). The right panels are enlargements from the light zone (magnification 80×). (A,B) Cells displaying nuclear staining for JUNB (blue) localize in the light zone (LZ) and show costaining for CD20 (brown). (C,D) Ki67 staining (brown) identifies the GC DZ (Ki67high) and LZ. GC cells expressing cytoplasmic TRAF1 (blue) are located mainly in the light zone.

JUNB expression and NF-κB activation in normal B cells. Immunofluorescence was performed for the c-Rel NF-κB subunit (red) and JUNB (green) on tonsillar sections. The upper panel shows a tonsillar GC (10 ×). The lower panels show the indicated GC regions at higher magnification (40 ×). In the DZ, B cells display cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB and absence of JUNB. In the LZ, a subset of CCs shows nuclear staining for c-Rel, and some of those cells coexpress JUNB (arrows).

JUNB expression and NF-κB activation in normal B cells. Immunofluorescence was performed for the c-Rel NF-κB subunit (red) and JUNB (green) on tonsillar sections. The upper panel shows a tonsillar GC (10 ×). The lower panels show the indicated GC regions at higher magnification (40 ×). In the DZ, B cells display cytoplasmic localization of NF-κB and absence of JUNB. In the LZ, a subset of CCs shows nuclear staining for c-Rel, and some of those cells coexpress JUNB (arrows).

Discussion

CD40 signature genes

The CD40 signature identified here comprises a substantial number of genes that were already reported as targets of CD40 signaling in various human and murine cell systems.4,57 Despite the difference in cell target (human transformed versus murine naive B cells) and an only partial overlap between the genes on the DNA microarrays used (human versus murine), about 40% of the CD40-regulated genes previously identified by gene expression analysis57 are also present in the CD40 signature reported here. These observations indicate that we have identified a bona fide gene expression response in B cells.

CD40 stimulation induces a rapid activation of NF-κB,20 and many CD40-induced genes are known to be NF-κB target genes. Accordingly, the CD40 signature included many genes previously reported to be NF-κB dependent (see “Results”). We observed up-regulation not only of inhibitor of kappaB alpha (IκB alpha), but also of IκB epsilon as well as of the precursor of the NF-κB subunit p50, confirming in our system the well-known role of NF-κB in the tight transcriptional regulation of its own components.58,59

CD40 signaling is known to activate not only NF-κB transcription factors, but also members of the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) family, in particular STAT3 and STAT6.60 Here we report an effect on the STAT members STAT1 and STAT5a at the transcriptional level. The up-regulation of the latter upon CD40 stimulation was reported to be NF-κB related,57 suggesting that the regulation of several transcription factors involved in CD40 signaling can also be a downstream effect of NF-κB.

Of note, genes that are known to be markers of GC B cells, such as CD38, BCL-6, and OCA-B,61-63 were down-regulated in the CD40 signature, consistent with a role of CD40 signaling at late/exit stages of the GC reaction.

Topographically sparse naive B cells may receive CD40 stimulation

The gene expression analysis showed evidence of CD40 signaling in naive B cells. Nonetheless, the mantle zone, the putative site of most naive B cells, displayed only rare cells expressing nuclear c-Rel staining. Additional B cells, showing NF-κB activation, were detected in the tonsillar epithelial area, which reportedly contains the presence of IgD+CD38- B cells,56 a population that comprises both unmutated naive B cells and somatically mutated memory B cells.64 These data suggest that the fraction of naive B cells receiving CD40 signaling may be large enough to display a CD40 signature in purified populations; yet these cells may be scattered in diverse regions within the lymphoid tissue. Consistent with this hypothesis, several observations suggest a role of CD40 signaling in naive B cells. First, combined CD40 and antigen receptor stimulation of naive B cells induces the expression of GC markers (down-regulation of surface IgM [sIgM] and sIgD, up-regulation of CD38, low expression of CD23).15,65 Second, the strength of the CD40 signal is reportedly a crucial factor in inducing the expression of the CB marker CD77 in naive B cells.66 Third, if CD40 signaling is impaired during early T-dependent immune response (days 1 to 3), GC formation is inhibited.67 Together with our results, these studies suggest a role of CD40 signaling in driving antigen-primed naive B cells to form a GC.

CD40 signaling is absent in GC centroblasts

The CD40 signature was not detectable in CBs and CCs sorted according to the expression of the CD77 marker, suggesting that in vivo CD40 signaling does not occur in the majority of GC B cells. This observation was supported by the immunostaining results of c-Rel, p65, TRAF1, and JUNB in normal tonsil sections, which showed the absence of NF-κB activation as well as CD40-induced genes in virtually all CBs of the dark zone and in most of the CCs of the light zone. In contrast with our results, a role for CD40 signaling in the GC was suggested by in vitro studies, demonstrating that CD40 stimulation was necessary for the survival of isolated GC B cells.68 In vivo the observation of spontaneous involution of established GCs upon block of CD40 signaling suggests an involvement in the maintenance of the GC structure affecting proliferation and/or rescue from apoptosis.67,69 However, GCs can form in the absence of T cells or under conditions that specifically block CD40 signaling, a finding not supporting a role for CD40 activity in the proliferation stage.70 Accordingly, our results indicate that CD40 signaling does not occur during the centroblastic phase of the GC reaction.

The absence of CD40 stimulation in GC B cells is also supported by the characteristic cellular composition of the GC structure. T cells are extremely rare in the dark zone, while they localize in the light zone together with follicular dendritic cells. Thus, consistent with our results, the cells that are able to deliver a CD40 stimulation are absent from the centroblast compartment.71,72 Furthermore, BCL-6, whose expression is known to be down-regulated by CD40 signaling, is highly expressed in CB, supporting the absence of CD40 activity in this population.73 Finally, our data are consistent with the previous observation that a subset of known NF-κB target genes is expressed at low levels in GC B cells.74

Although the gene expression profile data indicate the absence of CD40 signaling in GC B cells, immunohistochemical analysis showed that a small subset of CCs displays nuclear NF-κB and expresses CD40-induced genes (JUNB and TRAF1). It is certainly possible that signals other than CD40 induce NF-κB activation in these cells. However, several observations suggest a role for CD40 signaling in the processes occurring at the centrocytic stage. First, we have previously reported that CCs, isolated on the basis of the absence of the CD77 marker and expression of CD38 and CD10, represent a nonhomogeneous population.23 Thus, the presence of nuclear NF-κB may reflect genuine CD40 signaling in a fraction of cells, whose abundance is too low to be detected by gene expression profiling. Second, consistent with the presence of sparse nuclear NF-κB+ cells, CD40 signaling is a recognized player in the positive selection of B cells expressing high-affinity immunoglobulin occurring at the end of the GC reaction.14,75 Third, CD40 signaling is involved in further differentiation processes such as the immunoglobulin isotype-class switching that occurs specifically in the CCs.76 CD40 signaling induces germ line IH-CH transcription, which increases the accessibility of the targeted S region to the class-switch DNA-recombination machinery.77 Taken together, these observations and our results herein suggest that CD40 signaling may play an important role at the centrocytic stage, committing the cells to differentiate into memory B cells.

CD40 stimulation in memory B cells

We identified the presence of the CD40 signature in the gene expression profiles of normal memory B cells, suggesting an in vivo role of CD40 signaling in the generation and/or maintenance of memory B cells. Consistent with this observation, nuclear c-Rel was detectable in B cells in the subepithelium where most memory B cells localize.56 The presence of nuclear c-Rel suggests that those cells are receiving CD40 signaling and/or other stimuli leading to NF-κB activation. Accordingly, in vitro studies on isolated GC B cells showed that CD40 activation is involved in the generation of memory B cells and inhibits the differentiation into antibody-secreting cells.16,17,78,79 The importance of CD40 signaling in memory B-cell development has been demonstrated in mice by blocking the CD40-CD40L interaction using an antibody against CD40L or a soluble CD40-immunoglobulin fusion protein.80,81 Notably, the use of a soluble CD40-immunoglobulin fusion protein did not affect GC formation, but failed to induce differentiation into memory B cells.81 These observations, together with our results, suggest that CD40 signaling may be critical for the exit of B cells from the GC to become memory B cells, although a role in the maintenance of the memory cell phenotype cannot be excluded.

In summary, the results presented here do not support a role for the CD40 signaling pathway in GC expansion (centroblasts), which was previously suggested on the basis of in vitro experiments. Consistent with previous reports, our results support a model in which CD40 signaling contributes to the induction of the GC reaction and to the development of B cells toward memory B cells. The experimental approach used in this study should also be useful to track the activity of other signaling pathways in normal GC B cells and in B-cell lymphomas.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 26, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4291.

Supported by a fellowship from the American-Italian Cancer Foundation (K.B.), a fellowship from the Human Frontiers Science Program (U.K.), and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA-37295).

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to Vladan Miljkovic and Anamaria Babiac for technical assistance.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal