Abstract

Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) and proteinase 3 (PRO3) are myeloid tissue-restricted serine proteases, aberrantly expressed by myeloid leukemia cells. PRO3 and HNE share the PR1 peptide sequence that induces HLA-A*0201–restricted cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) with antileukemia reactivity. We studied the entire HNE protein for its ability to induce CTLs. In an 18-hour culture, HNE-loaded monocytes stimulated significant intracellular interferon γ (IFN-γ) production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 12 of 20 and 8 of 20 healthy individuals, respectively. Lymphocytes from 2 HNE responders were pulsed weekly for 4 weeks to generate HNE-specific CTLs. One of 2 HLA-A*0201–negative individuals inhibited the colony formation of HLA-identical chronic myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells (73% inhibition at 50:1 effector-target [E/T] ratio), indicating that peptides other than PR1 can induce leukemia-reactive CTLs. Repetitive stimulations with HNE in 2 of 5 HLA-A*0201+ individuals increased PR1 tetramer-positive CD8+ T-cell frequencies from 0.1% to 0.29% and 0.02% to 0.55%, respectively. These CTLs recognized PR1 peptide or killed HNE-loaded targets. These results indicate that exogenously processed HNE is a source of PR1 peptide as well as other peptide sequences capable of inducing leukemia-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. HNE could, therefore, be used in an HLA-unrestricted manner to induce leukemia-reactive CTLs for adoptive immunotherapy. (Blood. 2004; 103:3076-3083)

Introduction

Neutrophil azurophil granules are rich in the serine proteases proteinase 3 (PRO3) and neutrophil elastase (HNE) that both contain the peptide sequence PR1. This nonameric amino acid sequence is of immunotherapeutic interest because it can induce leukemia-specific cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) in HLA-A2–positive individuals.1-4 The basis of the specificity of CTLs for myeloid leukemias appears to be the aberrant expression of azurophil granule proteins in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) as well as in acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Like PRO3, HNE is a myeloid lineage-restricted protein5,6 and is highly expressed in the cytoplasm of myeloid leukemia cells.7 HNE overproduction in CML may contribute to the leukemic phenotype by reducing growth factor availability to residual normal hematopoietic progenitors.8,9 However, although PRO3 is implicated in the etiology of Wegener granulomatosis (WG),10-14 the ability of HNE to induce autoimmune T-cell responses is less, making it a more attractive candidate for generating leukemia-reactive CTLs.15,16

Although successful HLA class I–restricted immunotherapeutic approaches are possible with the PR1 peptide, they remain unavailable to patients who lack the HLA-A*0201 restriction element and may be poorly sustained in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help.17,18 The use of entire protein sequences, large enough to include a diversity of epitopes, binding to a wide range of HLA class I and II molecules, could overcome the limitations of peptide-based immunotherapy.19,20 However, the applicability of whole protein antigen in adoptive immunotherapy has shortcomings.21,22 Exogenous protein antigens are largely processed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II presentation to CD4+ T cells,23,24 whereas cytotoxic effects require CD8+ T-cell responses to peptides processed through class I pathways.22 Thus, induction of cytotoxic immune responses to soluble protein antigen depends on the degree to which the protein is degraded through a class I presentation pathway or on the ability of APCs to cross-present to CD8+ T cells.25-27

Because purified HNE and PRO3 are available commercially, we used them to model a protein-based immunotherapeutic approach to treat leukemia. Specifically, we looked for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to PRO3 and HNE and sought to determine whether these proteins both serve as parent proteins for the PR1 peptide. Here, we report the induction of leukemia-specific CTLs from healthy individuals by using HNE-pulsed APCs.

Materials and methods

Azurophil granule enzymes

HNE and PRO3 (Elastin Product Company, Owensville, MO) were reconstituted in 1:1 glycerol/0.02 M sodium acetate (NaOAc) and stored at -80°C until use. Their proteolytic activity was confirmed by fibronectin lysis (Biological Technologies, Stoughton, MA). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was reconstituted in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -20°C until use. HNE and PRO3 were enzymatically active and cytotoxic to monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs) during culture in serum-free medium. The enzymes were, therefore, inactivated at 56°C for 1 hour before use. This inactivation inhibited cytotoxicity to the same degree as the PMSF; HLA class I and class II molecule expression on APCs remained intact even after overnight culture in serum-free medium with heat-inactivated enzymes. All experiments described here were performed with heat-inactivated HNE and PRO3.

Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy stem cell transplantation donors and patients with leukemia were obtained from cryopreserved leukophoresis collections. CD3+ T lymphocytes were positively selected by anti-CD3 magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Lake Success, NY). The monocyte-enriched fraction was obtained by negative selection with anti-CD2 and anti-CD19 beads (Dynal Biotech). Freshly elutriated monocytes and lymphocytes from HLA-A*0201+ healthy donors were used to generate DCs with 800 U recombinant human interleukin 4 (rhIL-4) and 1000 U recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ).28 C1R-A2 cells were also used as HLA-A*0201+ APCs.29 For reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection of HNE-mRNA and as targets in the progenitor inhibition assay, CD34+ cells were selected by using anti-CD34 beads (Dynal Biotech) from donor granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–mobilized PBMCs or CML PBMCs. All subjects tested were enrolled in protocols approved by the institutional review board of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and gave written consent for research use of their blood cells.

Intracellular interferon-γ (IC IFN-γ) assay

The procedure was modified from Hensel et al30 and Waldrop et al.31 PBMCs (1 × 106) were cultured with 0 to 5.0 μg/mL HNE or PRO3 in combination with anti-CD28 (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) and anti-CD49d (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) in RPMI-1640 complete medium (RPMI-CM) (10 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid] buffer, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.065 mg/mL gentamicin; GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum (NABS; Gemini Bio-Product, Woodland, CA). After 2 hours of culture, Brefeldin A (Sigma) was added and cultured an additional 16 hours. After harvesting, cells were labeled with anti-CD3 (phycoerythrin [PE]), anti-CD4 (peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]), anti-CD8 (allophycocyanin) for cell surface antigens, and anti–human IFN-γ (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]) antibody (Becton Dickinson) for intracellular antigens as previously described.30 Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB) (Sigma) was used as positive control. Flow cytometric assay was performed by using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). A positive response was defined as follows: frequency (%) of IFN-γ–producing cells responding to enzyme ≥ mean + 3 SD of unstimulated cells.

In a previous study, we defined reproducibility of the assay by replicate testing IFN-γ production by 24 cytomegalovirus (CMV) seropositive subjects stimulated with a CMV-infected fibroblast lysate (AD169; Advanced Biotechnologies. Columbia, MD). The mean standard deviation (SD) of the replicates was ± 0.17% (range, 0.01%-0.65%) for CD8+ cells and ± 0.21% (range, 0.01%-0.69%) for CD4+ cells.30

Cell culture for CTL induction

CD3+ cells were stimulated weekly for up to 4 weeks with HNE- or PRO3-loaded monocytes or DCs at a 1:1 stimulator-responder ratio. For protein loading, monocyte-enriched cell fractions or DCs were cultured with HNE or PRO3 in serum-free RPMI-CM for 2 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. Residual lymphocytes in the monocyte-enriched fraction were removed by adhesion to plastic.32 T cells were cultured in monocyte-coated plates or with 75 Gy irradiated DCs in 10% NABS/RPMI-CM containing 10 ng/mL rhIL-7 and rhIL-12 (Biosource), in addition to 20 U IL-2 (rhIL-2; Tecin; Roche Pharmaceutical, Indianapolis, IN) 1 day after stimulation. After 4 stimulations, cultured cells were nonspecifically expanded with 50 U IL-2 and 30 ng/mL anti-CD3 antibody (Biosource International).

Surface antigen staining

Responder T cells were labeled with anti-CD3–PE, CD4-PerCP, CD8-allophycocyanin, and CD56-FITC antibodies (Becton Dickinson). G-CSF–mobilized normal donor PBMCs and PBMCs from patients with CML were stained with anti-CD34–FITC antibody. Flow cytometric assay and analysis were performed as described earlier.

PR1 tetramer staining

At time zero and after 4 stimulations, responder cells were stained with HLA-A*0201 PR1 tetramer-PE (PR1 peptide, VLQELNVTV) in combination with anti-CD3 (-FITC), anti-CD4 (-PerCP), CD8 (-allophycocyanin) (Becton Dickinson), or CD3 (-FITC), anti-CD8 (PerCP), and HLA-A*0201, WT1 tetramer-APC (WT1 peptide, RMFPNAPYL) to confirm the specificity for PR1 tetramer. Initially, cells were cultured with 1 μg PR1 tetramer for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing with 0.5% bovine serum albumen/phosphate-buffered saline (BSA/PBS), cells were labeled with other antibodies for cell surface markers at room temperature for 15 minutes. After washing once, cells were resuspended in 200 μL 1% paraformaldelyde (PFA)/PBS. Flow cytometric assay and analysis were then performed as described earlier.

CTL assay

CTL assay with Calcein-am (CAM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was performed as published elsewhere.33 This assay produces results comparable with the standard Cr51 release assay but requires fewer cells. In brief, HNE- or PRO3-loaded autologous monocytes were labeled with CAM and used as target cells at various effector-to-target (E/T) ratios. Nonprotein-loaded monocytes, keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; Sigma)–loaded monocytes, and K562 cells were also used as negative controls. HLA class I blocking was performed by using 10 μg/mL anti–class I antibody (clone W6/32; Immunotech, Westbrook, ME). Results were expressed as the mean of 6 replicates.

Cold target inhibition assay

To exclude nonspecific killing of targets by natural killer (NK) cells, unlabeled K562 cells (cold target) were added to CAM-labeled target cells (hot target) in a 10:1 ratio prior to CTL assay. Experiments were performed in 6 replicates.

PCR assay of peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell response

IFN-γ mRNA synthesis in response to PR1 peptide of responder cells was measured by quantitative real-time PCR established in our laboratory.34 In brief, after 4 stimulations with HNE- or PRO3-loaded DCs, mRNA was extracted from responder cells, IFN-γ cDNA and CD8 cDNA were amplified by PCR for 10 minutes at 95°C and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 1 minute. Primer sequences and TaqMan probe sequences (Custom Oligonucleotide Factory, Foster City, CA) were as follows: IFNγ (forward), 5′-AGCTCTGCATCGTTTTGGGTT-3′; IFN-γ (reverse), 5′-GTTCCATTATCCGCTACAT CTGAA-3′; IFN-γ (probe), FAM-TCTTGGCTGTTACTGCCAGGACCCA-TAMRA; CD8 (forward), 5′-CCCTGAGCAACTCCATCATGT-3′; CD8 (reverse), 5′-GTGGGCTTCGCTGGCA-3′; and CD8 (probe), FAM-CAGCCACTTCGTGCCGGTCTTC-TAMRA. Standard curve extrapolation of copy number was performed for both IFN-γ and CD8. Sample data were normalized by dividing the number of copies of IFN-γ transcripts by the number of copies of CD8 transcripts. All PCR assays were performed in duplicate. A 2-fold difference in gene expression was found to be within the discrimination ability of the assay. For the peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell response, at first, 1 × 106 responder cells were cultured for 3 hours with the same number of 0 to 10 μM PR1 peptide-loaded, 75 Gy irradiated CIR-A2 cells. Then responder cells were harvested, and quantitative PCR was performed as described earlier. In each assay, gp100 peptide (209-2M) was used as negative control. Results were shown as stimulation index (SI), dividing the number of IFN-γ transcript/CD8 transcripts following peptide stimulation with the no peptide control. An SI greater than 2.0 was used as the cutoff for significance, determined as the mean + 3 SD of response to the irrelevant negative control peptide gp100.

Colony inhibition assay

We used a granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-GM) colony inhibition assay35 to measure the effect of CTLs on leukemic progenitors, because progenitor inhibition assays best reflect the ability of infused leukemia-specific T cells to induce remissions in patients relapsing with leukemia after stem cell transplantation.36,37 Enriched CML-CD34+ cells were cocultured with CTL cells at various E/T ratios for 4 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. Unstimulated CD3+ cells and CD3 T cells treated with IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody (Biosource) were used as controls. Cells were transferred to 1% methylcellulose medium (Methcult H4230; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) containing 10 ng/mL GM-CSF (Biosource) and cultured in 6-well plates (1000 cells/well) for 10 to 14 days. In addition, anti–class I antibody (10 μg/mL) blocking experiments were performed. Results for triplicate target/responder combinations were expressed as mean ± SD.

Flow cytometric assay of intracytoplasmic HNE and PRO3 staining

Positively selected normal donor G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ cells and CML CD34+ cells (all > 96% positive for CD34+) were intracytoplasmically stained by anti-PRO3 monoclonal antibody (clone CLB12.8; Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY) or anti-HNE monoclonal antibody (clone NP57; Biomeda, Foster City, CA) as first antibodies in combination with goat antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)–FITC (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) as second antibody. Fixation and permeabilization were performed as previously reported.38 The promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL60 and Epstein-Barr virus lymphoblastoid cell lines EBV-LCL, established in our laboratory, were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Flow cytometric assay and analysis were performed as described earlier.

Detection of HNE and PRO3 mRNA in normal cells and CML CD34+ cells

HNE and PRO3 mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR. Each forward and reverse primer combinations were as follows: HNE, 5-CCACCATGACCC CCGCCGACTCGCTGTCTTTTCC-3′ and 5′-GCTCTAGAGAGAGTGGTGTGGGCAGCTGAGGTGACCCG-3′; PRO3, 5′-CTGCCACCATGGCTCACCGCCCC CAGCCCTGCCCTGGCGTC-3′ and 5′-CGTTCAGACAAAGATCCGCCTCGAGGTTTGG GCCAGGCTC-3′. PCR condition included 94°C for 5 minutes, and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. Finally, PCR products were extended at 72°C for 7 minutes.

Results

Healthy individuals have circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells responding to HNE and PRO3

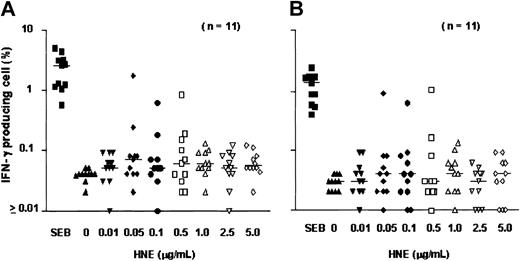

After 18 hours of exposure of PBMCs to HNE or PRO3, low frequencies of IFN-γ–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected. Dose-finding experiments were performed in 11 healthy individuals; responses were observed at doses ranging from 0.05 to 5.0 μg/mL HNE, but without clear dose relationship. T-cell frequencies ranged between 0.01% and 1.73% for CD4+ and between 0.01% and 1.01% for CD8+ T cells (Figure 1). In total, 20 healthy individuals (donors 1-20) were screened against HNE doses of 0.05 to 5.0 μg/mL. Significant responses to tested doses of HNE were seen in 12 and 8 individuals in CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively (Figure 2). By using the same dose range as HNE, T-cell responses to PRO3 were also examined. Significant responses to PRO3 were seen in 12 and 11 individuals in CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively. Responses to PRO3 were generally weaker than those seen with HNE (Figure 3). There was no significant difference by chi-square analysis in the probability of responding to HNE or PRO3 according to HLA type: 11 subjects typed as HLA-A*0201, 4 were responders to HNE and 5 to PRO3. Nine subjects were HLA-A*0201 negative, 4 were responders to HNE and 6 to PRO3. These results suggested that numerous HLA class I and II molecules can present HNE and PRO3 to T cells.

T-cell response to HNE: dose-finding experiments. PBMCs from 11 individuals were tested for IC IFN-γ production after exposure to HNE (0-5.0 μg/mL). (A) CD4 cells. (B) CD8 cells. SEB indicates Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (positive control). Horizontal bars indicate median.

T-cell response to HNE: dose-finding experiments. PBMCs from 11 individuals were tested for IC IFN-γ production after exposure to HNE (0-5.0 μg/mL). (A) CD4 cells. (B) CD8 cells. SEB indicates Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (positive control). Horizontal bars indicate median.

HNE-induced IFN-γ production. Data points represent highest response achieved from HNE concentrations between 0.05 and 5.0 μg/mL in 20 subjects. (A) CD4+ T cells. (B) CD8+ T cells. Horizontal bar indicates median. Dashed line represents the cutoff value for significance (background + 3 SD).

HNE-induced IFN-γ production. Data points represent highest response achieved from HNE concentrations between 0.05 and 5.0 μg/mL in 20 subjects. (A) CD4+ T cells. (B) CD8+ T cells. Horizontal bar indicates median. Dashed line represents the cutoff value for significance (background + 3 SD).

PRO3-induced IFN-γ production. Data points represent highest response achieved from PRO3 concentrations between 0.05 and 5.0 μg/mL in 20 subjects. (A) CD4+ cells. (B) CD8+ cells. Horizontal bar indicates median. Dashed line represents the cutoff value for significance (background + 3 SD).

PRO3-induced IFN-γ production. Data points represent highest response achieved from PRO3 concentrations between 0.05 and 5.0 μg/mL in 20 subjects. (A) CD4+ cells. (B) CD8+ cells. Horizontal bar indicates median. Dashed line represents the cutoff value for significance (background + 3 SD).

IFN-γ production in response to HNE is APC dependent

A representative experiment is shown in Figure 4. This subject (donor 7) was HLA-A*0201 negative, and the highest responses to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells occurred at a dose of 0.05 μg/mL HNE. After depletion of the APC fraction from PBMCs, pure CD4+/CD3+/CD56- and CD3+/CD56- T cells showed only background frequencies of IFN-γ production (< 0.02%) when HNE was added at all tested doses, indicating that the T-cell response to HNE was APC dependent.

Flow cytometric analysis of HNE response in an HLA-A*0201–negative individual (donor 7; HLA A24,30, B38,58, Cw12,7, DRβ1*13,*7, DQβ1*6,*2). (A) HNE response in PBMC samples. (B) Loss of response to HNE in APC-depleted selected T cells.

Flow cytometric analysis of HNE response in an HLA-A*0201–negative individual (donor 7; HLA A24,30, B38,58, Cw12,7, DRβ1*13,*7, DQβ1*6,*2). (A) HNE response in PBMC samples. (B) Loss of response to HNE in APC-depleted selected T cells.

HNE and PRO3 share multiple antigens

Because HNE and PRO3 have 55% homology in their amino acid sequences (Figure 5), we investigated the possibility that the 2 proteins share multiple antigens. In initial experiments with HLA-A*0201-negative subjects, HNE- and PRO3-exposed T cells showed cross-recognition in cytotoxicity assays of PRO3-pulsed targets by HNE-stimulated T cells and vice versa (Table 1). Five HLA-A*0201+ healthy individuals were then examined with the use of a PR1 tetramer to detect amplification of PR1-specific T cells after repeated stimulation with HNE- or PRO3-pulsed DCs (Table 2). After 4 stimulations with HNE, 2 individuals showed a significant increase of PR1 tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells (0.29% and 0.55%, respectively). The same individuals stimulated by PRO3 also induced PR1 tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells (1.17% and 0.40%, respectively). The PR1 peptide-specific response was also identified by quantitative PCR for IFN-γ mRNA (SI, 3.32 with 0.1 μM and 3.54 with 10 μM PR1) in donor 21. Although quantitative PCR failed to show peptide-specific IFN-γ production because of a high background response to C1R-A2 cells in donor 25, the CTL assay demonstrated HNE-specific killing.

Amino acid homology between HNE and PRO3. Top rows are PRO3, and bottom rows are HNE. I indicates identity; a colon (:) indicates 2; and a period (.) indicates 1; all are match display threshold by Gap-Global Alignment. PR1 sequence is underlined.

Amino acid homology between HNE and PRO3. Top rows are PRO3, and bottom rows are HNE. I indicates identity; a colon (:) indicates 2; and a period (.) indicates 1; all are match display threshold by Gap-Global Alignment. PR1 sequence is underlined.

Shared epitopes of HNE and PRO3 revealed by cross-recognition of HNE- and PRO3-specific T cells

. | HNE-primed CD3 . | . | PRO3-primed CD3 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 20:1 E/T ratio . | 5:1 E/T ratio . | 20:1 E/T ratio . | 5:1 E/T ratio . | ||

| HNE/Mo, % | 10.8 | 1.6 | 19.2* | 4.3* | ||

| PRO3/Mo, % | 14.1* | 1.7* | 5.6 | 2.3 | ||

| Mo, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

. | HNE-primed CD3 . | . | PRO3-primed CD3 . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 20:1 E/T ratio . | 5:1 E/T ratio . | 20:1 E/T ratio . | 5:1 E/T ratio . | ||

| HNE/Mo, % | 10.8 | 1.6 | 19.2* | 4.3* | ||

| PRO3/Mo, % | 14.1* | 1.7* | 5.6 | 2.3 | ||

| Mo, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Lymphocytes from donor 12 were stimulated 3 times with HNE- or PRO3-loaded monocytes, and their cytotoxicity against HNE- or PRO3-loaded targets was measured in the Calcein-am release assay.

Significant responses.

PRI peptide is naturally processed from either HNE or PRO3 in HLAA*0201-positive individuals

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | CTL activity, % . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. . | HLA type . | . | . | . | . | Phenotype, % . | . | PR1 tetramer+ cells in CD8, % . | . | . | PR1, μM/mL . | . | . | HNE, μg/mL . | . | KLH, μg/mL . | . | |||||||||||

| . | A . | B . | Cw . | DRβ1 . | DQβ1 . | CD4 . | CD8 . | Before . | HNE . | PRO3 . | 0.1 . | 1.0 . | 10 . | 1.0 . | 1.0 + K562 . | 0 . | 10 . | |||||||||||

| D21 | 0201,30 | 18,44 | 0501,— | 04,13 | 03,06 | 71.3 | 25.7 | 0.1* | 0.29* | 1.17* | 3.32* | — | 3.54* | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||

| D22 | 01,0201 | 08,40 | 03,07 | 0101,0701 | 0501,02 | 22.4 | 76.4 | — | 0.01 | 0.0 | — | NR | NR | 12.4 | 0 | 2.5 | 4.3 | |||||||||||

| D23 | 0201,68 | 07,8101 | 1505,18 | 13,— | 05,06 | 5.3 | 94.4 | — | 0.02 | 0.04 | — | NR | NR | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||

| D24 | 0201,3101 | 07,35 | 04,07 | 0407,1501 | 0301,06 | 13.5 | 86.2 | — | 0.01 | 0.11* | — | NR | NR | 50.4* | 20.4* | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| D25 | 0201,30 | 13,4501 | 0602,1601 | 07,— | 02,— | 23.4 | 77.4 | 0.02* | 0.55* | 0.40* | — | Inc | Inc | 31.4* | 26.3* | 6.0 | 4.0 | |||||||||||

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | CTL activity, % . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case no. . | HLA type . | . | . | . | . | Phenotype, % . | . | PR1 tetramer+ cells in CD8, % . | . | . | PR1, μM/mL . | . | . | HNE, μg/mL . | . | KLH, μg/mL . | . | |||||||||||

| . | A . | B . | Cw . | DRβ1 . | DQβ1 . | CD4 . | CD8 . | Before . | HNE . | PRO3 . | 0.1 . | 1.0 . | 10 . | 1.0 . | 1.0 + K562 . | 0 . | 10 . | |||||||||||

| D21 | 0201,30 | 18,44 | 0501,— | 04,13 | 03,06 | 71.3 | 25.7 | 0.1* | 0.29* | 1.17* | 3.32* | — | 3.54* | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||

| D22 | 01,0201 | 08,40 | 03,07 | 0101,0701 | 0501,02 | 22.4 | 76.4 | — | 0.01 | 0.0 | — | NR | NR | 12.4 | 0 | 2.5 | 4.3 | |||||||||||

| D23 | 0201,68 | 07,8101 | 1505,18 | 13,— | 05,06 | 5.3 | 94.4 | — | 0.02 | 0.04 | — | NR | NR | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||

| D24 | 0201,3101 | 07,35 | 04,07 | 0407,1501 | 0301,06 | 13.5 | 86.2 | — | 0.01 | 0.11* | — | NR | NR | 50.4* | 20.4* | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| D25 | 0201,30 | 13,4501 | 0602,1601 | 07,— | 02,— | 23.4 | 77.4 | 0.02* | 0.55* | 0.40* | — | Inc | Inc | 31.4* | 26.3* | 6.0 | 4.0 | |||||||||||

CD3+ T cells from 5 healthy individuals (donors 21-25) were stimulated 4 times with HNE- or PRO3-loaded DCs. CD8+ T-cell responses to PR1 peptide are shown as stimulation indices (see “Cold target inhibition assay” for details). NR indicates no response;—, not done (because of insufficient cell numbers, not all peptides were tested in all cases); and Inc, high IFN-γ mRNA copy number but inconclusive because of high background to control. CTL assay data were obtained at 10:1 E/T ratio. Representative data are from 3 independent experiments are shown.

Significantly positive results.

Induction of HNE-specific CTLs

Two individuals (donors 7 and 12) with high frequencies of HNE-specific T cells were used to generate HNE-specific CTLs. Both were HLA-A*0201 negative. After 4 stimulations of donor 7 with 0.05 μg/mL HNE-loaded autologous monocytes, CD8+ T cells predominated (CD8+, 63%; CD4+, 37%; CD56+, 0.5%). Unselected T cells showed specific cytotoxicity to 1 μg/mL HNE-pulsed autologous monocytes (24% at 10:1 E/T ratio), with no significant cytotoxicity to 10 μg/mL KLH-pulsed or unpulsed monocytes or K562 cells. Cytotoxicity was blocked by an anti–class I antibody, and cold target inhibition with unlabeled K562 cells confirmed CTL target specificity for HNE (Figure 6A-C). Significant but lower numbers of HNE-specific CTLs were also induced in donor 12 by 4 stimulations with 0.5 μg/mL HNE-pulsed monocytes, because highest responses both to CD4 and CD8 were produced by using 0.5 μg/mL HNE. Effectors were CD8+, 38%; CD4+, 60%; and CD56+, less than 0.1% (Figure 6D-E). These results indicated that HNE-specific CTLs can be induced by repeated stimulation.

Induction of HNE-specific CTLs in 2 donors. (A-C) Donor 7. (A) After 4 stimulations, CD3+ T cells showed dose-dependent cytotoxicity to HNE-loaded autologous monocytes. No response was noted with KLH, unloaded APCs, or K562 cells. Representative data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Cold target inhibition assay to exclude nonspecific killing by NK and NK-T cells confirmed HNE-specific cytotoxicity by CTLs. (C) Abrogation of CTL activity by 10 μg antihuman HLA class I antibody (23.9% versus 3.9%, respectively). Data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Donor 12 (HLA; A03,-, B07,15, Cw03,0702, DRβ1*01,*1001, DQβ1*05,*1). HNE-specific CTLs were induced after 4 stimulations. Representative data are from 3 independent experiments.

Induction of HNE-specific CTLs in 2 donors. (A-C) Donor 7. (A) After 4 stimulations, CD3+ T cells showed dose-dependent cytotoxicity to HNE-loaded autologous monocytes. No response was noted with KLH, unloaded APCs, or K562 cells. Representative data from 3 independent experiments are shown. (B) Cold target inhibition assay to exclude nonspecific killing by NK and NK-T cells confirmed HNE-specific cytotoxicity by CTLs. (C) Abrogation of CTL activity by 10 μg antihuman HLA class I antibody (23.9% versus 3.9%, respectively). Data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Donor 12 (HLA; A03,-, B07,15, Cw03,0702, DRβ1*01,*1001, DQβ1*05,*1). HNE-specific CTLs were induced after 4 stimulations. Representative data are from 3 independent experiments.

CML cells express HNE and are targets for HNE-specific CTLs

We examined intracellular HNE expression in 3 patients with CML by flow cytometry. CD34+ cells were positively selected from CML PBMCs. Samples contained more than 96% CD34+ cells. Compared with the strongly cytoplasmic HNE-expressing myeloid leukemia line HL60, CML-CD34+ cells were weakly positive, whereas EBV-LCL and CD34+ cells from G-CSF–mobilized PBMCs of healthy donors were negative (Figure 7). HNE mRNA was measured by PCR in 2 CML and 2 normal CD34+ cell samples. CML cells and the HL60 line showed clear PCR products, whereas normal CD34+ cells did not. These findings confirm that CML CD34+ cells aberrantly express intracytoplasmic HNE. An HLA-A*0201–negative donor and HLA-identical chronic phase CML sibling recipient was then studied. HNE-reactive CTLs from the donor (donor 7) were generated by repeated pulsing with HNE-loaded autologous monocytes and tested for their ability to inhibit CML CFU-GM. Responder cells stimulated by HNE inhibited CFU-GM formation in a dose-dependent manner (maximum 73% at 50:1 E/T ratio) (Figure 8). Inhibition was abrogated by 10 μg anti–class I antibody (73% versus 31% at 50:1 E/T ratio, P < .001 by 2-tailed t test). Conversely, CD3+ T cells of donor 7 not stimulated with HNE-loaded autologous monocytes did not significantly inhibit CFU-GM colony formation, and control IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody-treated donor CD3+ cells had a modest stimulatory effect on CML CFU-GM. These observations excluded the possibility that CFU-GM inhibition was mediated nonspecifically by LAK cells and confirmed that HNE-primed CTLs inhibit CML progenitor growth.

CMLs, but not normal CD34 cells, express HNE. (A) Intracytoplasmic HNE in CML-CD34+ cells (HLA-identical sibling of donor 7) was identified by flow cytometry. Positive control, HL60 cells; negative controls, LCL and normal G-CSF mobilized PBMC CD34+ cells. Filled histogram indicates IgG1-FITC control. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each sample and IgG1 control is shown in italics and parentheses, respectively. (B) mRNA detection: lanes 1-2, G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ cells from 2 healthy donors; lanes 3-4, CML-CD34+ cells from 2 patients in chronic phase; lane 5, HL60-positive control; lane 6, dH2O, GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) quantitative control for RNA.

CMLs, but not normal CD34 cells, express HNE. (A) Intracytoplasmic HNE in CML-CD34+ cells (HLA-identical sibling of donor 7) was identified by flow cytometry. Positive control, HL60 cells; negative controls, LCL and normal G-CSF mobilized PBMC CD34+ cells. Filled histogram indicates IgG1-FITC control. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each sample and IgG1 control is shown in italics and parentheses, respectively. (B) mRNA detection: lanes 1-2, G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ cells from 2 healthy donors; lanes 3-4, CML-CD34+ cells from 2 patients in chronic phase; lane 5, HL60-positive control; lane 6, dH2O, GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) quantitative control for RNA.

HNE-primed CTLs (donor 7) are cytotoxic to CML progenitor cells. (A) HNE-primed CTLs (CD3+/HNE) significantly inhibited HLA-identical CML CFU-GM colony formation. (B) Abrogation of inhibition by 10 μg antihuman mouse HLA class I antibody *P < .001 (t test). (C) No significant colony inhibition by untreated CD3+ T cells. (D) No inhibition by T cells nonspecifically expanded with IL-2 and anti-CD3 (See “CML cells express HNE and are targets for HNE-specific CTLs” for details).

HNE-primed CTLs (donor 7) are cytotoxic to CML progenitor cells. (A) HNE-primed CTLs (CD3+/HNE) significantly inhibited HLA-identical CML CFU-GM colony formation. (B) Abrogation of inhibition by 10 μg antihuman mouse HLA class I antibody *P < .001 (t test). (C) No significant colony inhibition by untreated CD3+ T cells. (D) No inhibition by T cells nonspecifically expanded with IL-2 and anti-CD3 (See “CML cells express HNE and are targets for HNE-specific CTLs” for details).

Discussion

By using the IC IFN-γ assay, we found that 40% to 60% of healthy individuals have circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognizing HNE and PRO3. Responses were observed with relatively low protein concentrations of 0.05 to 5.0 μg/mL, suggesting high antigen affinity for several protein-derived antigens. Responses occurred in healthy individuals without any history of autoimmune disease and with diverse HLA types. This finding suggests that low frequencies of HNE- and PRO3-specific T cells, probably recognizing a variety of peptide epitopes, are a normal occurrence. The presence of autoreactive T cells in the absence of disease could indicate that in vivo azurophil granule proteins are not normally presented to responding T cells, or that these proteins have induced T-cell tolerance.

HNE and PRO3 share more than 55% identity in their amino acid sequences, and both molecules contain the PR1 peptide sequence that can induce CTLs specific for leukemia cells overexpressing PRO3.1 We, therefore, sought to determine whether both PRO3 and HNE serve as a source of PR1. CD8+ T cells were generated from HLA-A*0201+ healthy individuals stimulated with PRO3- or HNE-loaded DCs. Two of 5 individuals stimulated with HNE showed a PR1 response by tetramer assay, quantitative PCR for IFN-γ, and cytotoxicity against HNE-loaded targets. One had a detectable frequency of PR1-specific CD8+ cells by tetramer assay before stimulation, suggesting that the protein stimulation enhanced a preexisting memory response to PR1. In both cases, PR1-specific responses were induced by HNE and by PRO3. We also found that HNE and PRO3 induced protein-specific CD8+ and CD4+ cells in HLA-A*0201–negative individuals that did not recognize PR1. Our experiments, therefore, demonstrated the existence of HNE and PRO3 peptides other than PR1, capable of inducing both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

To generate HNE-specific CTL for further study, we selected high responders in the IC IFN-γ assay and pulsed their lymphocytes weekly with autologous protein-loaded monocytes. This monocyte-enriched population from PBMCs may retain monocyte-DC precursors responsible for antigen presentation.39 However, it is more likely that the cells responsible for antigen presentation were CD13/CD14+ monocytes that express MHC class I, class II, costimulatory and adhesion molecules CD80, CD54, and CD11a.32 In our study, HNE-loaded monocytes were also a target for HNE-primed CD4+ and CD8+ cells, supporting the possibility that these APCs process exogenous HNE protein. Our results further confirm observations by other investigators that monocytes loaded with exogenous proteins can be used to induce CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses.25,40 After 4 weekly restimulations, we generated an HNE protein-specific CTL line. Cytotoxicity against protein-loaded targets was blocked by an anti–MHC class I antibody, indicating that the effect was most likely mediated through CD8+ MHC class I interaction.

Finally, we carried out experiments to determine whether HNE-specific CTLs could exert cytotoxicity against CML cells. We looked for HNE expression in leukemic progenitor cells by using intracytoplasmic antibody staining and RT-PCR. In contrast to normal CD34 cells, which were universally negative, patients with CML had detectable mRNA for HNE, as well as for PRO3, and weak protein expression of HNE and PRO3 (data not shown). Our results confirm observations that indicate the absence of azurophil granule protein expression in normal CD34+ cells41,42 and the presence of those proteins in CML CD34+ cells.3,7,43,44 An HNE-specific cell line was generated from a healthy individual who was also the HLA identical sibling donor of a patient with CML. This line showed strong inhibition of the CML CFU-GM and to HNE-loaded (but not unloaded) APCs, indicating the induction by HNE of leukemia-reactive CTLs. The generation of CTL in this HLA-A*0201–negative pair indicates that HNE contains more peptide sequences than PR1 capable of inducing leukemia-specific cytotoxicity.

Our studies suggest that HNE, PRO3, and possibly other azurophil granule proteins could be used to induce CTLs against leukemias aberrantly expressing or overexpressing azurophil granule proteins. The use of whole protein rather than defined peptides offers the opportunity to generate leukemia-specific CTLs against multiple peptide epitopes, thus eliminating the constraint of HLA restriction and allowing the generation of CD4+ T cells, which could provide help for CD8+ T-cell expansion. Experience with adoptive T-cell therapy to control EBV-lymphoproliferative disease after stem cell transplantation has shown that CD8+ T-cell clones persist much longer in the presence of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.45

Before using protein-specific T-cell lines in the adoptive therapy of leukemia, it would, however, be necessary to ensure by extensive tissue screening that critical normal tissues are not subject to recognition and damage by the T-cell line. Autoantibodies to HNE are occasionally detected in WG and autoimmune vasculitis. However, unlike PRO3, T cells specific for HNE have not been conclusively found in these conditions, suggesting that HNE might be a safer protein to target than PRO3.11,12,14,15

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 4, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2424.

Supported by grants from MEDIC (Medical Equipment Distribution Information Centre) Foundation. D.A.P. is a Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) Clinician Scientist Fellow.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal