Abstract

Childhood cancer survivors transfused before 1992 are at risk for chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection. In 1995, St Jude Children's Research Hospital initiated an epidemiologic study of childhood cancer survivors with transfusion-acquired HCV. Of the 148 survivors with HCV confirmed by second-generation enzyme immunoassay, 122 consented to participate in the study. Their current median age is 29 years (range, 9 to 47 years). At enrollment, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing indicated chronic infection in 81.1%; genotype 1 was the most common viral genotype. Liver biopsy in 60 patients at a median of 12.4 years from the diagnosis of malignancy showed mild (28.8%) or moderate (35.6%) fibrosis; 13.6% had cirrhosis. Elevated body mass index was associated with histologic findings of increased steatosis (P = .008). Antimetabolite chemotherapy exposure was associated with early progression of fibrosis. Significant quality-of-life deficits were observed in noncirrhotic adult survivors. Antiviral therapy resulted in clearance of infection in 17 (44%) of 38 patients to date. Six patients have died; 1 patient with decompensated cirrhosis died of variceal bleeding. Despite a young age at HCV infection, the progression of liver disease in childhood cancer survivors is comparable to that seen in adults.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common etiology of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Although the transmission of this disease has declined since the development of blood donor screening tests for the virus, there are many patients surviving with chronic transfusion-acquired infection. The natural history of chronic infection and the role of the immune system in the progression of chronic disease are complex and poorly understood; some patients resolve the infection spontaneously, but most remain chronically infected. In some chronically infected patients, HCV progresses to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Little is known about the natural history of hepatitis C infection in children. The tempo from childhood infection to development of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma has not been established. Young age at infection has been proposed to be a determinant for the lack of progression of HCV infection and hepatocellular damage.1,2 However, others have proposed that the immunocompetence of the host3,4 and the mode of infection5 modify the natural history of infection. Further, the adverse impact of HCV on quality of life (QOL) has been described in adults but not in patients infected during childhood. QOL measurements are thus an important component of natural history studies in conjunction with the endpoints of survival and liver function.

Our goal is to evaluate long-term outcomes in childhood cancer survivors with chronic transfusion-acquired HCV infection.6 This report serves to update the clinical progress of the St Jude HCV seropositive cohort of survivors of childhood cancer. Herein, we correlate our cohort's demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors with liver function, viral genotype and load, clinical and histologic liver disease, QOL, and response to antiviral therapy.

Patients, materials, and methods

Identification and HCV testing of patients who received blood products

We identified all St Jude patients with cancer or aplastic anemia diagnosed before July 1992; these patients were at risk for receiving blood products prior to the initiation of HCV blood donor screening by second-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA-2; Abbott Diagnostic 2.0; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). The institutional HCV testing protocol follows the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) and has been previously described.6,7 Patients were considered to have been infected with HCV if anti-HCV antibodies were detected by both EIA-2 and recombinant immunoblot assay-2 (RIBA-2; Chiron RIBA HCV 2.0 Strip Immunoblot assay; Chiron, Emeryville, CA) or if quantitative or qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Roche Amplicor Monitor HCV; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Somerville, NJ) (sensitivity, 600 IU/mL) testing detected HCV RNA, regardless of EIA-2 or RIBA-2 results.

Protocol enrollment and assessment

Patients with evidence of HCV infection were asked to participate in the long-term epidemiologic study of HCV infection and HCV-related outcomes. Although screening efforts targeted patients diagnosed with cancer or aplastic anemia before July 1992, patients diagnosed after July 1992 with HCV infection were also invited to participate in the study. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained before patients were enrolled. At enrollment, patients self-reported demographic information and divulged any history of drug and alcohol use. Cohort participants undergo comprehensive annual evaluations that include completion of QOL questionnaires, laboratory studies of hematologic and chemical parameters and viral load and genotype, ultrasound evaluation of liver architecture and portal flow, and a clinical assessment of liver function by a hepatologist. Liver biopsies were routinely performed before the initiation of antiviral therapy. A study pathologist reviewed all of the histologic specimens and graded findings in a standard and consistent format using the modified histologic activity index.8 Steatosis was also graded on a scale of 0 to 3 on the basis of the percentage of hepatocytes in the biopsy involved: 0, none; 1, less than 33%; 2, 33% to 66%; and 3, more than 66%.

Treatment decisions with regard to antiviral therapy varied based on physician preference and currently available antiviral agents. Thirty-eight patients received interferon (IFN) alpha (3 million units, 3 times per week) or combination antiviral therapy with IFN and ribavirin (600 mg, twice daily) or pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN; 0.5 μg/kg weekly) and ribavirin (600 mg, twice a day). The decision to begin treatment was based on the presence of persistent viremia and liver dysfunction, as indicated by elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity and a prior liver biopsy indicating chronic, active inflammation with progressive fibrosis. Pathology results, quantitative viral data, and ALT values were obtained before and after treatment for all patients.

Quality-of-life assessment

Selected items from the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised (SCL-90R) questionnaire9 were used to assess psychologic functioning and health status of the cohort. Responses refer to the level of discomfort the problem has caused the patient during the previous week and are rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). To allow a comparison to normative data from 974 healthy adults, only cohort patients aged 18 years or older at the time of their first assessment were included in the QOL analysis. Responses were dichotomized consistent with normative data as a problem (categories 1-4) versus not at all a problem (category 0). Consistent with QOL research in HCV-infected cohorts,10 we excluded patients with cirrhosis from our QOL assessment, because the QOL data from these patients can be unduly influential.

Comparisons were performed using a binomial test considering the normative values as constant, given the large sample size. For these exploratory comparisons, we applied a study-level alpha of 0.1 for statistical significance.11 Applying a sequential multiple-comparison correction12 would require that P values less than .013 for this particular study be considered statistically significant to achieve a study-wise alpha of 0.1 when making 19 comparisons.

Health status was assessed by the survivor's report about how he or she felt or what activities could be performed in the previous week. Responses were graded on a 7-point scale from 1 (felt well, able to carry on daily activities, work, or go to school) being normal to 7 (had severe problems and complaints, was unable to work or attend school, and required assistance for self-care) representing a debilitated state. To correlate health status with biologic parameters, we dichotomized the health status responses (ie, responses 1 or 2, unimpaired; responses 3-7, impaired) and then analyzed them using the Fisher exact test.

Results

Seroprevalence of HCV infection among survivors of childhood cancer

Before July 1992, there were 7348 patients with cancer or aplastic anemia treated at St Jude who were at risk of contracting HCV by blood-product transfusion. Of the 3889 patients alive at study inception (December 1995), 2356 (60.6%) had a history of blood-product transfusion at St Jude or elsewhere. Screening by EIA-2 identified 186 transfused patients who were seropositive for HCV (HCV+) prior to 1992. Of these, 143 cases were confirmed by RIBA or PCR. In addition, 5 HCV+ patients with malignancies diagnosed after July 1992 were confirmed: 3 were international patients transfused before arrival to our institution; one received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant from an HCV+ sibling donor; and one was a 4-year-old girl who had no obvious source of infection other than the blood transfusion provided during treatment for childhood leukemia. Both of her parents tested negative for hepatitis C.

Of the 148 HCV+ patients, 122 are participating in the cohort study as of November 2002 and are the subjects of this report. The median elapsed time between last follow-up of surviving study participants and the preparation of this report is 4.5 months (range, 0.2-25.7 months); 90% of the patients were seen within the last 12 months. Assuming infection at diagnosis of malignancy, which would represent a ceiling, the median duration of infection is 19.5 years (range, 5.5-38.8 years). Details regarding a proportion of this cohort have been previously reported.6,13

Characteristics of the HCV+ population

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort (n = 122) are summarized in Table 1. The cohort was evenly distributed by sex; 62 male patients and 60 female patients participated. The median age at diagnosis of primary malignancy was 5 years (range, 0-20 years), and the median age at the time of this report was 29 years (range, 9-47 years). The race distribution of the cohort is similar to the distribution of patients treated at the institution during the study period with a preponderance of white patients. Leukemia was the most common presenting malignancy. Seven patients in the cohort were survivors of bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

Demographic characteristics of 122 HCV+ childhood cancer survivors

Characteristic . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | 50.8 |

| Female | 60 | 49.2 |

| Race | ||

| White | 100 | 82 |

| Black | 17 | 13.9 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 0.8 |

| Other | 4 | 3.3 |

| Primary cancer | ||

| Leukemia | 94 | 77 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 69 | 73.4 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 23 | 24.5 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 | 2.1 |

| Lymphoma | 4 | 3.3 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 | 75 |

| Hodgkin disease | 1 | 25 |

| Central nervous system tumors | 2 | 1.6 |

| Colon cancer | 1 | 0.8 |

| Sarcoma | 7 | 5.7 |

| Osteosarcoma | 6 | 85.7 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 14.3 |

| Embryonal tumor | 13 | 10.7 |

| Neuroblastoma | 6 | 46.2 |

| Hepatoblastoma | 1 | 7.7 |

| Germ cell tumors | 4 | 30.8 |

| Wilms tumor | 2 | 15.4 |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 | 0.8 |

| Status | ||

| Alive | 116 | 95.1 |

| Dead | 6 | 4.9 |

Characteristic . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 62 | 50.8 |

| Female | 60 | 49.2 |

| Race | ||

| White | 100 | 82 |

| Black | 17 | 13.9 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 0.8 |

| Other | 4 | 3.3 |

| Primary cancer | ||

| Leukemia | 94 | 77 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 69 | 73.4 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 23 | 24.5 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 | 2.1 |

| Lymphoma | 4 | 3.3 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 | 75 |

| Hodgkin disease | 1 | 25 |

| Central nervous system tumors | 2 | 1.6 |

| Colon cancer | 1 | 0.8 |

| Sarcoma | 7 | 5.7 |

| Osteosarcoma | 6 | 85.7 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 14.3 |

| Embryonal tumor | 13 | 10.7 |

| Neuroblastoma | 6 | 46.2 |

| Hepatoblastoma | 1 | 7.7 |

| Germ cell tumors | 4 | 30.8 |

| Wilms tumor | 2 | 15.4 |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 | 0.8 |

| Status | ||

| Alive | 116 | 95.1 |

| Dead | 6 | 4.9 |

The median number of blood donor exposures was 13.5 (range, 1-430 exposures). None of the patients in the cohort were infected with HIV; however, 3 patients were coinfected with HBV.

Clinical evidence of liver disease

PCR testing for HCV was positive in 81.1% (n = 99) at study enrollment; most recent PCR testing indicated that 71.3% (n = 87) remain HCV infected (Table 2). For those patients with positive PCR findings, the median viral load at study entry was 699 258 IU/mL (range, 6129 to > 850 000 IU/mL). At the most recent follow-up, the median viral load of this group was 621 081 IU/mL (range, 18 444 to > 850 000 IU/mL); 43.7% (n = 38) currently have viral loads more than 850 000 IU/mL. At enrollment, a median of 15.9 years (range, 1.9-37.5 years) since primary cancer diagnosis, only 27.1% (n = 32) of the entire cohort had elevated ALT levels (median, 0.7 × upper normal limit (UNL); range, 0.1-8.1 × UNL for the entire cohort). Genotype 1 was the most common (76.8%) viral genotype detected at study entry; genotype 2 was the second most common (18.2%) (Table 2).

Comparison of PCR, ALT, and genotype results at enrollment

PCR results . | No. patients at enrollment (%)† . |

|---|---|

| HCV-PCR+ | 99 (81.1) |

| Normal ALT | 63 |

| Abnormal ALT | 32 |

| ALT not available* | 4 |

| HCV-PCR- | 23 (18.9) |

| Normal ALT | 23 |

| Abnormal ALT | 0 |

| ALT not available* | 0 |

| P value‡ | < .001 |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1 | 76 (76.8) |

| 2 | 18 (18.2) |

| 3 | 4 (4) |

| 4 | 1 (1) |

PCR results . | No. patients at enrollment (%)† . |

|---|---|

| HCV-PCR+ | 99 (81.1) |

| Normal ALT | 63 |

| Abnormal ALT | 32 |

| ALT not available* | 4 |

| HCV-PCR- | 23 (18.9) |

| Normal ALT | 23 |

| Abnormal ALT | 0 |

| ALT not available* | 0 |

| P value‡ | < .001 |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1 | 76 (76.8) |

| 2 | 18 (18.2) |

| 3 | 4 (4) |

| 4 | 1 (1) |

ALT activity was determined within 1 month of PCR analysis

PCR results are reported for 122 patients; of these, HCV genotyping was done in 99 at enrollment

Fisher exact test of association between PCR and ALT

PCR findings were negative at enrollment in 18.9% (n = 23) of the patients in whom EIA and RIBA had detected evidence of HCV infection; these patients represent a subset of the cohort who had resolved infection without treatment (n = 17), had previously received antiviral therapy (n = 5), or had a brief period of undetectable virus (n = 1) (Table 2). ALT was normal in all of the patients who had resolved infection (median, 0.3 × UNL; range, 0.1-1.0 × UNL). Patients with persistent viremia were more likely to have abnormal ALT activity compared with those who had resolved infection (P < .001). Univariate analysis did not identify variables of age at diagnosis, sex, race, tumor type (solid tumor vs leukemia), or number of blood donor exposures as being related to “self-clearance” of virus in the aforementioned patients; however, this analysis was limited by small sample size. BMT survivors represented only 5.7% (n = 7) of the cohort. This small number precludes statistical assessment of differences in long-term liver-related outcomes for this group.

Since enrollment in the study, 6 patients have died. One death was due to variceal bleeding in a patient with decompensated cirrhosis at 19.3 years from cancer diagnosis. Two deaths were caused by accidents. The remaining 3 cohort patients died of aspiration, heart disease, or a second cancer.

Histologic features of chronic hepatitis C

Liver biopsies performed in 60 patients for the evaluation of abnormal serum ALT, or for consideration of antiviral therapy, or both, were included in this analysis; 3 patients who had liver biopsy for cancer staging at diagnosis were excluded. The most recent biopsy was performed a median of 12.4 years (range, 0.2-37.7 years) after diagnosis of primary malignancy. The median age of patients at the time of biopsy was 20 years (range, 4-43 years). Centrally reviewed biopsy results are described in Table 3. Histologic findings in 38 (64%) biopsies showed mild or moderate fibrosis with staging as follows: stage 1 (n = 11), stage 2 (n = 6), stage 3 (n = 19), stage 4 (n = 1), and stage 5 (n = 1). Eight patients had biopsy-confirmed cirrhosis (stage 6); another patient had clinical features of decompensated cirrhosis but a biopsy had not been performed. None of the BMT survivors or patients with cirrhosis was coinfected with HBV.

Results of the most recent liver biopsies performed on 60 HCV-infected childhood cancer survivors

Result* . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Piecemeal necrosis (score) | 55 | |

| Absent (0) | 10 | 18.2 |

| Mild (1) | 19 | 34.5 |

| Moderate (2-3) | 26 | 47.3 |

| Severe (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Staging (score)† | 59 | |

| None (0) | 13 | 22.0 |

| Mild fibrosis (1-2) | 17 | 28.8 |

| Moderate fibrosis (3-5) | 21 | 35.6 |

| Cirrhosis | 8 | 13.6‡ |

| Bile duct lesion | 53 | |

| Absent | 48 | 90.6 |

| Present | 5 | 9.4 |

| Iron storage (score) | 50 | |

| Absent or barely discernable (0) | 32 | 64.0 |

| Discernable 100-400 × (1-2) | 7 | 14.0 |

| Discernable 10-25 × (3-4) | 11 | 22.0 |

| Steatosis (score) | 50 | |

| Absent (0) | 18 | 36.0 |

| Mild (1) | 27 | 54.0 |

| Moderate (2) | 5 | 10.0 |

| Severe (3) | 0 | 0 |

Result* . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| Piecemeal necrosis (score) | 55 | |

| Absent (0) | 10 | 18.2 |

| Mild (1) | 19 | 34.5 |

| Moderate (2-3) | 26 | 47.3 |

| Severe (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Staging (score)† | 59 | |

| None (0) | 13 | 22.0 |

| Mild fibrosis (1-2) | 17 | 28.8 |

| Moderate fibrosis (3-5) | 21 | 35.6 |

| Cirrhosis | 8 | 13.6‡ |

| Bile duct lesion | 53 | |

| Absent | 48 | 90.6 |

| Present | 5 | 9.4 |

| Iron storage (score) | 50 | |

| Absent or barely discernable (0) | 32 | 64.0 |

| Discernable 100-400 × (1-2) | 7 | 14.0 |

| Discernable 10-25 × (3-4) | 11 | 22.0 |

| Steatosis (score) | 50 | |

| Absent (0) | 18 | 36.0 |

| Mild (1) | 27 | 54.0 |

| Moderate (2) | 5 | 10.0 |

| Severe (3) | 0 | 0 |

Not all categories were scored for each patient

Fibrosis was scored using the 6-point scale per Desmet et al.8

Does not include one case of clinically decompensated cirrhosis, not biopsied

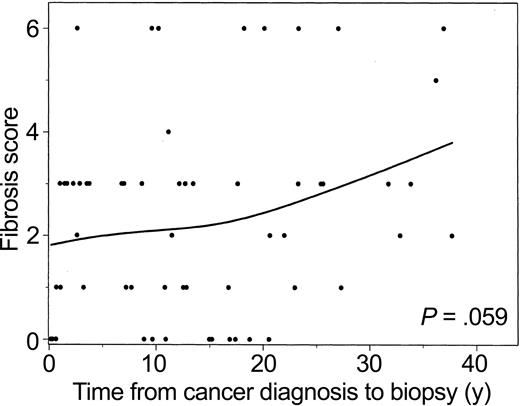

Fibrosis score versus years from cancer diagnosis to biopsy is plotted with a smoothed (spline) line (Figure 1). These data suggest that in this group, fibrosis increases with increasing time from diagnosis. However, when this trend was further investigated using an exact ordinal test for decade since cancer diagnosis versus fibrosis score, the relationship was not significant (P = .059). One influential observation was a patient with cirrhosis 2.6 years after diagnosis; without this observation, the association was stronger (P = .027). There was no detectable correlation between the rate of steatosis and progression to fibrosis in this select group.

Fibrosis score versus years from cancer diagnosis to liver biopsy. Data from 59 patients were analyzed. The P values were determined using the exact ordinal test of linear-by-linear association for decade since cancer diagnosis versus fibrosis score (P = .059). The line was estimated using spline-smoothing techniques.

Fibrosis score versus years from cancer diagnosis to liver biopsy. Data from 59 patients were analyzed. The P values were determined using the exact ordinal test of linear-by-linear association for decade since cancer diagnosis versus fibrosis score (P = .059). The line was estimated using spline-smoothing techniques.

Because of the increased incidence of obesity in childhood cancer survivors, we evaluated the association between body mass index (BMI) and the presence of steatosis, piecemeal necrosis, and fibrosis on liver biopsy. Of those with a BMI at or above the 95th percentile, 92.3% (n = 12/13) had mild-to-moderate steatosis, compared with only 50% (n = 17/34) of those with BMI below the 95th percentile (P = .008). Piecemeal necrosis of the liver was apparent in 100% of obese patients and in 76% of those with a BMI less than 95%, but this association was only suggestive (P = .090). There was no association detected between BMI and fibrosis staging (P = .808).

Influence of cancer treatment variables on histologic outcomes

We evaluated the relationship of hepatotoxic chemotherapy to self-clearance of virus, and to the development of early fibrosis in patients who were biopsied less than 10 years from cancer diagnosis (Table 4). Among the patients who had multiple biopsies, we based analysis and correlation to treatment variables on the biopsy that revealed the highest fibrosis stage. Too few patients received abdominal radiation to include this modality as a variable contributing to hepatotoxicity. A chemotherapy score was assigned on the basis of the number and class (alkylating agents, antimetabolites, tumor antibiotics, other) of chemotherapeutic agents. The median chemotherapy score was 7 (range, 3-12). There was no relationship between chemotherapy score and fibrosis. However, a higher rate of grade 3-6 fibrosis was significantly associated with treatment including a greater number of antimetabolites.

Demographic/medical variables versus fibrosis for patients with biopsies less than 10 years from diagnosis (n = 34 patients)

. | Fibrosis score . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | 0-2 n = 16 (%) . | 3-6 n = 18 (%) . | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Female | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Race* | |||

| White | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | |

| Black | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispancic/other | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| 0-6 | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| 7-20 | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| ALL/AML | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | |

| Other malignancies | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Genotype† | |||

| 1 | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Other | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| No. of alkylating agents | |||

| 0 | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| 1 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| No. of antimetabolites* | |||

| 0 | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| 1 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| 2 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| 3-4‡ | 8 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No. of antibiotics | |||

| 0 | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | |

| 1 | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | |

| 2 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Chemotherapy score§ | |||

| Mean ± SD | 6.7 ± 2.7 | 7.6 ± 2.5 | |

| Median (range) | 6.5 (3-11) | 7 (3-12) | |

. | Fibrosis score . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | 0-2 n = 16 (%) . | 3-6 n = 18 (%) . | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Female | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Race* | |||

| White | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | |

| Black | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispancic/other | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| 0-6 | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| 7-20 | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| ALL/AML | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | |

| Other malignancies | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Genotype† | |||

| 1 | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Other | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| No. of alkylating agents | |||

| 0 | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| 1 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| No. of antimetabolites* | |||

| 0 | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| 1 | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| 2 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| 3-4‡ | 8 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | |

| No. of antibiotics | |||

| 0 | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | |

| 1 | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | |

| 2 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Chemotherapy score§ | |||

| Mean ± SD | 6.7 ± 2.7 | 7.6 ± 2.5 | |

| Median (range) | 6.5 (3-11) | 7 (3-12) | |

No significant differences were detected.

Significant association (P < .05) between variable and fibrosis score. Two categories are presented, but fibrosis score was analyzed as ordinal values ranging from 0 to 6 using exact tests, given the small sample sizes (linear-by-linear association tests for individual chemotherapy agents and Kruskal-Wallis categorical tests for sex through genotype)

Genotype only available on 14 subjects

One patient in the 3-6 fibrosis score group had 4 antimetabolites. The remaining patients had 3

For chemotherapy score, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test and ordinary least squares regression were used

Impact of alcohol and drug use

Alcohol and drug use were abstracted from patient report forms and categorized according to the U.S. Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey.14 By self-report at study enrollment, 60% of patients were lifetime abstainers from alcohol, 13% were former users, 17% admitted to light alcohol intake (12 or more drinks in past year but fewer than 3 drinks per week; < 30 g/d), 7% were moderate drinkers (3-13 drinks per week; 0-49 g/d), and 2% were heavy drinkers (2 or more drinks per day; ≥ 50 g/d). The analysis correlating alcohol use to liver histology was limited by a temporal difference between the time of biopsy and the survey results, that is, 60% had their biopsy before the survey. Fifteen percent of the cohort admitted to a history of drug use, with 7% being limited to marijuana use only. These results simply underscore the fact that substance abuse was not a major contributor to the accelerated course of liver damage in this cohort.

Quality of life

At enrollment, 110 subjects completed QOL assessments using items from the SCL-90R. Responses from 73 adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) without cirrhosis were compared with normative data derived from population controls (Table 5). Notably, the mean age for our sample (29 years) was younger than that for the normative adult sample (46 years). Compared with normative adult respondents, significantly more HCV+ adult patients disclosed a history of feeling low in energy (P = .013), muscle aches or soreness (P < .001), and mind going blank (P < .001) in the preceding week. The significance of this association for the latter 2 items persisted even after accounting for patients' reported alcohol and drug use.

Quality of life (SCL-90R) at first enrollment in HCV study

. | All HCV+ patients . | . | All adult HCV+ patients . | . | Adult HCV+ patients without cirrhosis* . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Normative adult data (N = 974) . | Unadjusted P† . | |||

| Nausea or upset stomach | 108 | 27.8 | 80 | 31.3 | 71 | 25.4 | 22.7 | .679 | |||

| Pains in heart or chest | 110 | 20.9 | 81 | 22.2 | 72 | 22.2 | 16.2 | .225 | |||

| Headaches | 110 | 54.5 | 81 | 55.6 | 72 | 55.6 | 54.8 | .995 | |||

| Pains in lower back | 110 | 47.3 | 81 | 54.3 | 72 | 51.4 | 37.0 | .018 | |||

| Muscle aches or soreness | 110 | 46.4 | 81 | 54.3 | 72 | 52.8 | 29.9 | < .001‡ | |||

| Feeling low in energy | 110 | 62.7 | 81 | 67.9 | 72 | 66.7 | 51.5 | .013‡ | |||

| Trouble concentrating | 110 | 36.4 | 81 | 39.5 | 72 | 34.7 | 27.2 | .197 | |||

| Trouble remembering things | 110 | 53.6 | 81 | 58.0 | 72 | 56.9 | 42.3 | .017 | |||

| Mind going blank | 110 | 37.3 | 81 | 44.4 | 72 | 43.1 | 15.8 | < .001‡ | |||

| Feeling depressed | 110 | 38.2 | 81 | 42.0 | 72 | 40.3 | 32.6 | .209 | |||

| Feeling no interest in things | 110 | 30.0 | 81 | 30.9 | 72 | 27.8 | 19.3 | .103 | |||

| Feeling tense or keyed up | 108 | 46.3 | 79 | 55.7 | 70 | 52.9 | 47.8 | .467 | |||

| Worrying too much about things | 109 | 57.8 | 80 | 65.0 | 71 | 62.0 | 55.7 | .345 | |||

| Crying easily | 109 | 31.2 | 80 | 32.5 | 71 | 26.8 | 16.2 | .032 | |||

| Feeling easily annoyed or irritated | 108 | 49.1 | 79 | 48.1 | 70 | 42.9 | 56.8 | .026 | |||

| Faintness or dizziness | 108 | 20.4 | 79 | 21.5 | 70 | 18.6 | 17.2 | .857 | |||

| Heart pounding or racing | 108 | 19.4 | 79 | 21.5 | 70 | 20.0 | 20.0 | .999 | |||

| Trouble getting breath | 108 | 20.4 | 79 | 17.7 | 70 | 15.7 | 13.9 | .761 | |||

| Decreased interest in sex | 88 | 29.5 | 73 | 34.2 | 65 | 32.3 | 21.1 | .047 | |||

. | All HCV+ patients . | . | All adult HCV+ patients . | . | Adult HCV+ patients without cirrhosis* . | . | . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question . | n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Normative adult data (N = 974) . | Unadjusted P† . | |||

| Nausea or upset stomach | 108 | 27.8 | 80 | 31.3 | 71 | 25.4 | 22.7 | .679 | |||

| Pains in heart or chest | 110 | 20.9 | 81 | 22.2 | 72 | 22.2 | 16.2 | .225 | |||

| Headaches | 110 | 54.5 | 81 | 55.6 | 72 | 55.6 | 54.8 | .995 | |||

| Pains in lower back | 110 | 47.3 | 81 | 54.3 | 72 | 51.4 | 37.0 | .018 | |||

| Muscle aches or soreness | 110 | 46.4 | 81 | 54.3 | 72 | 52.8 | 29.9 | < .001‡ | |||

| Feeling low in energy | 110 | 62.7 | 81 | 67.9 | 72 | 66.7 | 51.5 | .013‡ | |||

| Trouble concentrating | 110 | 36.4 | 81 | 39.5 | 72 | 34.7 | 27.2 | .197 | |||

| Trouble remembering things | 110 | 53.6 | 81 | 58.0 | 72 | 56.9 | 42.3 | .017 | |||

| Mind going blank | 110 | 37.3 | 81 | 44.4 | 72 | 43.1 | 15.8 | < .001‡ | |||

| Feeling depressed | 110 | 38.2 | 81 | 42.0 | 72 | 40.3 | 32.6 | .209 | |||

| Feeling no interest in things | 110 | 30.0 | 81 | 30.9 | 72 | 27.8 | 19.3 | .103 | |||

| Feeling tense or keyed up | 108 | 46.3 | 79 | 55.7 | 70 | 52.9 | 47.8 | .467 | |||

| Worrying too much about things | 109 | 57.8 | 80 | 65.0 | 71 | 62.0 | 55.7 | .345 | |||

| Crying easily | 109 | 31.2 | 80 | 32.5 | 71 | 26.8 | 16.2 | .032 | |||

| Feeling easily annoyed or irritated | 108 | 49.1 | 79 | 48.1 | 70 | 42.9 | 56.8 | .026 | |||

| Faintness or dizziness | 108 | 20.4 | 79 | 21.5 | 70 | 18.6 | 17.2 | .857 | |||

| Heart pounding or racing | 108 | 19.4 | 79 | 21.5 | 70 | 20.0 | 20.0 | .999 | |||

| Trouble getting breath | 108 | 20.4 | 79 | 17.7 | 70 | 15.7 | 13.9 | .761 | |||

| Decreased interest in sex | 88 | 29.5 | 73 | 34.2 | 65 | 32.3 | 21.1 | .047 | |||

Data from 7 patients with cirrhosis confirmed by biopsy and from one patient with clinically decompensated cirrhosis were removed

P values were based on exact binomial tests comparing results for adult HCV+ patients without cirrhosis with normative results considering the normative values as constant

Individual P values less than .013 give a significant .10 study-wise alpha level based on the Holm multiple-comparison procedure

Results of the first health status assessment collected at study entry were correlated with results from ALT assays and PCR analysis. Twenty percent of the cohort reported having problems and complaints so severe that activities of daily living were difficult or impaired some or all of the time. Although impaired health status was more frequently reported by survivors whose HCV PCR analysis was positive and ALT activity was elevated (> 1 XUNL; P = .024), the association disappeared when the 9 patients with cirrhosis were removed from the analysis (P = .301).

Outcome of antiviral therapy

Among the 60 patients who underwent liver biopsy, 21 did not receive antiviral therapy. One patient who received antiviral therapy is excluded from our analysis, because details were not available at the time of this report. Reasons for not pursuing antiviral therapy were as follows: asymptomatic infection with normal liver function (n = 11), medical or psychiatric contraindication for therapy (n = 4), subsequent resolution of infection (n = 2), death prior to initiation of treatment (n = 1), or patient declined therapy (n = 1). Two patients are pending initiation of antiviral therapy.

Antiviral therapy was recommended for 38 study participants who had persistently elevated ALT or biopsy confirmation of fibrosis or cirrhosis; 19 of these had received antiviral treatment prior to or at the time of study entry. The median age at initiation of antiviral therapy was 25 years (range, 4-44 years), and the median time from completion of cancer therapy was 14.7 years (range, 0.7-38.6 years). Therapeutic approaches used over the study period varied with the availability of newer antiviral agents; these included IFN alone, IFN in combination with ribavirin, or PEG-IFN with ribavirin. Response was defined as a persistently negative PCR for 6 months after completion of therapy. Therapy responses are summarized in Table 6. The median duration of IFN therapy was 6 months (range, 2.8-13 months); 6 of 20 (30%) patients responded to IFN.

Antiviral therapy in 38 HCV infected childhood cancer survivors

Treatment . | No. patients . | Responders . | Nonresponders . | On therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN | 20 | 6 | 14* | 0 |

| IFN + ribavirin | 16 | 7 | 9† | 0 |

| Primary therapy | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Secondary therapy | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| PEG-IFN + ribavirin | 11 | 4 | 2‡ | 5 |

| Primary therapy | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Secondary therapy | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Treatment . | No. patients . | Responders . | Nonresponders . | On therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN | 20 | 6 | 14* | 0 |

| IFN + ribavirin | 16 | 7 | 9† | 0 |

| Primary therapy | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Secondary therapy | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| PEG-IFN + ribavirin | 11 | 4 | 2‡ | 5 |

| Primary therapy | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Secondary therapy | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; PEG-IFN, pegylated interferon.

Includes 2 patients unable to complete therapy because of psychosis (1) or depression (1)

Includes 2 patients unable to complete therapy due to severe anemia (1) and hypothyroidism (1)

Includes 1 patient unable to complete therapy due to depression; this patient was also taken off interferon for the same reason

Subsequently, 16 patients, including 4 patients who failed IFN monotherapy, received combination antiviral therapy with IFN and ribavirin. The duration of 2-drug therapy was 7.0 months (range, 0.9-12.8 months). Of these, 7 (44%) have shown persistently HCV-negative PCR. To date, 11 patients in the cohort have received PEG-IFN and ribavirin; 5 of these patients experienced previous treatment failure with other approaches. Four (67%) of 6 patients who completed PEG-IFN/ribavirin therapy have experienced a sustained response, and 5 patients are not yet evaluable for response. Overall, 71% of patients infected with genotype 1 were responders, compared with 36% of those infected with other genotypes (odds ratio = 4.4; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.7-28.0).

Discussion

Although many early investigations of transfusion-acquired HCV in children2 and survivors of childhood cancer 3,15-17 reported a mild clinical course, we now appreciate that a significant number of patients are at risk for adverse outcomes including impaired QOL, cirrhosis, hepatic failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.6,13 This report demonstrates the progressive nature of transfusion-acquired chronic HCV with a median of 19 years of infection in a group who were children at the time of initial infection; the evidence herein challenges the current thought that HCV infection at a younger age is associated with a lower risk of adverse liver outcomes.1,2

Our histologic outcomes are similar to the clinical rates of end-stage liver disease seen in larger adult cohorts with transfusion-associated hepatitis18 and in hemophiliacs with concomitant HCV and HIV infection, some of whom were also coinfected with HBV.19,20 The poor liver outcomes and rapid tempo of clinical and histologic liver disease are especially notable in our young cohort who have a low rate of coinfection with HBV, no coinfection with HIV, and include only a small subgroup of patients who have undergone BMT. These data suggest that either the immunosuppressive effects of cancer chemotherapy or the hepatotoxic effects of chemotherapy have a role in acceleration of liver disease. Treatment with antimetabolite chemotherapy appears to be one of the mitigating factors.

In this follow-up to our initial report on this cohort,6 the estimated seroprevalence of HCV for our pediatric oncology population transfused before 1992 is unchanged. However, this in fact may be an underestimate, as screening did not capture some infected patients who died prior to the inception of this cohort. In addition, it is possible that transfused patients whose EIA-2 analysis was HCV- and who did not have an episode of hepatitis prompting PCR evaluation could have been missed by our screening methods.21,22 The limitation of a prospective study including a survivor cohort also underestimates mortality and morbidity of HCV infection, as an ongoing retrospective study of liver-related mortality at our institution demonstrates 5 additional confirmed HCV-related deaths due to hepatic failure (n = 3) or early evolution to hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 2).13 The 14% rate of viral clearance in the absence of antiviral therapy was equivalent to previous reports of the course of HCV in childhood cancer survivors3,16 and in an adult series.18 Analysis of the demographic and clinical factors of our cohort was limited by the small sample size and failed to reveal clinical predictors of self-resolution of infection. Additionally, it should be noted that in this exploratory setting, P values were often not adjusted for multiple comparisons and that the possibility of finding a significant finding by chance alone is increased.

The impact of HCV on adult QOL noted here is comparable with that seen in noncirrhotic adults infected with HCV, 10,23-25 despite the younger age of our cohort. This finding suggests that QOL and health status are compromised in childhood cancer survivors with chronic HCV. However, the present QOL analysis is limited by the availability of a comparison control group of childhood cancer survivors matched for age, sex, race, and treatment. Future studies will need to address this prospectively by evaluating QOL before and after completion of antiviral therapy. In addition, the impact of chronic infection on QOL of younger patients requires comparison to that of an age-appropriate control population, as this issue has not been characterized in children.

Steatosis, which is often related to alcohol consumption, is thought to be a significant contributor to the progression of liver disease26,27 and to the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected adults.28 In attempting to define clinical predictors for liver disease progression, we identified obesity as a risk factor for non–alcohol-related steatosis in this cohort. An increased rate of obesity has been well characterized in childhood cancer survivors29-31 and represents a comorbid condition that increases the risk for a variety of other health conditions including cardiovascular disease and second malignancy. Accordingly, this is a potential area for more aggressive intervention in HCV-infected cancer survivors. The lack of an association between fibrosis and BMI does not negate the effect of obesity on liver damage, as it may be that with advancing fibrosis and cirrhosis, nutritional status of the survivors is changed.

The response to antiviral therapy observed in our cohort appears to be similar to that of other patients with chronic HCV32-34 and has improved with the advent of combination drug regimens. Our limited patient number prevents ascertainment of host or viral factors predicting response to antiviral therapy at this time. However, the generally good compliance and low incidence of adverse effects to antiviral therapy suggest that aggressive treatment with combination PEG-IFN and ribavirin is a reasonable approach in these young patients. Further, it appears that lack of response to monotherapy does not preclude a trial of combination PEG-IFN and ribavirin in childhood cancer survivors.

The inconsistent use of liver biopsy in patients with chronic infection, especially those with normal levels of ALT activity, has limited our ability to assess a potential correlation between histologic findings and clinical outcomes in all natural history studies of HCV infection. The importance of liver biopsy data in patients with HCV is demonstrated by the high incidence of fibrosis and cirrhosis seen in the present cohort. These data suggest that repeated biopsy once every decade is indicated in many of these patients. Conversely, although biopsy is important to determine severity of disease and hence indications for treatment, clinical severity may at times preclude biopsy, as it has been described in patients with hemophilia and chronic HCV infection.19,20

In conclusion, although many previous cohorts that acquired HCV infection during childhood have indicated minimal morbidity of chronic infection, our experience indicates that HCV+ children with comorbidity, such as childhood malignancy, represent a unique population at risk for hepatic sequelae of chronic HCV infection. Hence, these children benefit from earlier biopsy and therapeutic intervention with antiviral drug regimens. The present follow-up indicates that adverse outcomes do not yet exceed that seen in most adult cohorts, although the tempo of disease does appear accelerated.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 18, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2565.

Supported by grant RO1 CA 85891-05 and Cancer Center Support P30 CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal