Abstract

p18INK4c is a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor that interferes with the Rb-kinase activity of CDK6/CDK4. Disruption of p18INK4c in mice impairs B-cell terminal differentiation and confers increased susceptibility to tumor development; however, alterations of p18INK4c in human tumors have rarely been described. We used a tissue-microarray approach to analyze p18INK4c expression in 316 Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs). Nearly half of the HL cases showed absence of p18INK4c protein expression by Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells, in contrast with the regular expression of p18INK4c in normal germinal center cells. To investigate the cause of p18INK4c repression in RS cells, the methylation status of the p18INK4c promoter was analyzed by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bisulfite sequencing. Hypermethylation of the p18INK4c promoter was detected in 2 of 4 HL-derived cell lines, but in none of 7 non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)–derived cell lines. We also detected p18INK4c hypermethylation, associated with absence of protein expression, in 5 of 26 HL tumors. The correlation of p18INK4c immunostaining with the follow-up of the patients showed shorter overall survival in negative cases, independent of the International Prognostic Score. These findings suggest that p18INK4c may function as a tumor suppressor gene in HL, and its inactivation may contribute to the cell cycle deregulation and defective terminal differentiation characteristic of the RS cells.

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) are a group of low-molecular-weight proteins that associate with cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), blocking their activity.1,2 The inhibitors of CDK4 (INK4) family of CKIs is composed of p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d, which specifically bind and inhibit CDK4 and CDK6, thereby preventing cyclin D–dependent phosphorylation of Rb.1

Inactivation of the genes comprising the INK4 family of cell-cycle inhibitors is a frequent phenomenon in human cancer, although it seems to be mostly restricted to p16INK4a and p15INK4b silencing through genetic3 and epigenetic4 mechanisms. Alterations of both p16INK4a and p15INK4b have been described in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)5-7 and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).8,9 In these hematologic neoplasias, hypermethylation of the 5′ cytidine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG) island of these genes seems to be a frequent event, whereas the incidence of homozygous deletion and mutations is relatively low.10,11 Unsurprisingly, this hypermethylation status of the promoter region correlates with transcriptional repression of these genes and constitutes an alternative inactivating mechanism.6,12

The human p18INK4c gene was first identified in a yeast interaction screen that searched for CDK6-interacting proteins.13 p18INK4c was demonstrated to interact with CDK6 and more weakly with CDK4 (but not with other CDKs) both in vivo and in vitro, and to inhibit the kinase activity of cyclin D–CDK6 complexes. Ectopic expression of p18INK4c was shown to suppress cell growth in a wild-type Rb-dependent manner.13 p18INK4c has been proposed to function as a tumor suppressor gene, based on the observation that p18INK4c-null mice display an increased susceptibility to developing spontaneous and induced tumors, such as pituitary adenomas and others.14,15 However, alterations in the p18INK4c gene are strikingly less frequent than those affecting p16INK4a or p15INK4b, having been observed in human cancer only sporadically.16-19

Although in normal lymphoid B cells the p18INK4c protein has been implicated in key functions such as cell cycle control and terminal (plasma cell) differentiation,19,20 most studies performed in lymphoid neoplasms have shown preservation of the gene and its expression,21,22 except for myeloma-derived cell lines and, more rarely, tumors, where occasional homozygous deletions have been demonstrated.23,24 These findings could be considered unexpected due to the structural and functional homology of p18INK4c to p16INK4a and p15INK4b, and its key role in cell cycle control. Nevertheless, all of these previous analyses largely ignored HL and HL-derived cell lines.

As the neoplastic Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells in HL constitute a paradigm of cell cycle arrest resistance25 and defective B-cell terminal differentiation,26,27 we hypothesized that inactivation of the p18INK4c gene might contribute to the disruption of the cell cycle control machinery in this neoplasia. Using a tissue microarray (TMA) approach, we examined p18INK4c protein expression in normal lymphoid tissue and in a group of common B-cell lymphomas including follicular center (FCL), mantle cell (MCL), diffuse large B-cell (DLBCL), and Burkitt (BL) lymphomas, and compared the findings with a series of 316 HL tumors. Our results show loss of p18INK4c protein expression in 45.3% of HL tumors compared with a normal expression pattern in the majority of NHLs. Furthermore, this loss of protein expression is frequently related with a hypermethylated status of the promoter region of the p18INK4c gene in both HL-derived cell lines and tumors, as demonstrated by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bisulfite sequencing. Finally, loss of p18INK4c protein in the RS cells of some HL tumors is associated with an unfavorable treatment response and a worse clinical outcome, underlining the biologic and clinical relevance of this phenomenon.

Patients, materials, and methods

Tumor samples and cell lines

There were 316 retrospective cases of HL collected by collaborating members of the Spanish Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group.25 The histologic confirmation of HL and subtype was determined by central review using standard tissue sections, and diagnoses were made according to the criteria of the WHO classification.28 Cases included 171 cases of nodular sclerosis HL, 112 cases of mixed-cellularity HL, 14 cases of lymphocyte-rich classical HL, 9 cases of lymphocyte-depletion HL, and 10 cases of nodular lymphocyte–predominant HL. All of the samples included represent at-diagnosis biopsies and all of the patients were treated following standard protocols: patients with advanced HL were mainly treated with 6 to 10 courses of combination chemotherapy (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine [ABVD] or variants), whereas low-risk patients received extended-field radiotherapy or 2 to 4 courses of chemotherapy plus involved-field radiotherapy.

Paraffin-embedded blocks from reactive lymphoid tissue (reactive lymph nodes and tonsils) and 20 different NHL samples (including 6 FCL, 4 MCL, 6 DLBCL, and 4 BL) were obtained from the tissue archives of the CNIO Tumor Bank. These samples were included as internal controls in all the TMAs.

We obtained 4 HL-derived cell lines (L-540, HDLM-2, KM-H2, and L-428) and 7 NHL-derived cell lines (RAJI and NAMALWA, Burkitt lymphoma; GRANTA-519, mantle cell lymphoma; WSU-NHL, KARPAS-422, and DOHH-2, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with t(14;18); RPMI-8226, multiple myeloma) from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweigh, Germany). All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% to 20% fetal calf serum (GIBCO), glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin.

TMA design and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

We used a Tissue Arrayer device (Beecher Instrument, Sun Prairie, WI) to construct the TMAs as previously described.25,29 Included in each case were 2 selected 1-mm-diameter cylinders from 2 different areas, along with the different controls to ensure the quality, reproducibility, and homogenous staining of the slides. The robustness and reproducibility of this technique for analyzing HL have been previously demonstrated.25,30,31

TMA blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 3 μm and dried for 16 hours at 56°C before being dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antigen retrieval was achieved by heat treatment in a pressure-cooker for 2 minutes in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.5). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked and immunohistochemical staining was performed on these sections using a monoclonal anti-p18INK4c antibody (118.2, sc-9965; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Immunodetection was performed with the LSAB Visualization System (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) using diaminobenzidine chromogen as substrate. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

The pattern of staining was recorded as positive or negative, depending on the expression in RS cells. Any degree of nuclear expression was considered as positive staining, since all p18INK4c-positive cases showed a significant amount of positive RS cells, although the intensity was variable from case to case. We considered as negative cases those without any noticeable p18INK4c nuclear expression in the tumoral cells. Reactive benign lymphocytes and plasma cells served as internal controls of the technique.

IHC techniques for p18INK4c protein expression were also performed on cytospin preparations of the different HL-derived cell lines fixed in ethanol/acetone (vol/vol), using the same procedures described for tissue sections.

Western blot

For extraction of total protein, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl, pH 7.4, 130 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes and cleared by centrifugation. Approximately 80 μg protein was electrophoresed in 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred overnight onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were sequentially incubated with blocking solution (5% nonfat milk in PBS/0.1% Tween 20), the appropriate dilution of the primary antibody (1:100 for p18INK4c and 1:10 000 for α-tubulin), and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (DAKO). Finally, the blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). The antibodies used were anti-p18INK4c (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti–α-tubulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as a loading control.

Bisulfite treatment of DNA and methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

MSP is based on the selective conversion of cytosine, but not methylcytosine, to uracyl by sodium bisulfite, followed by PCR amplification using specific primers that allow the discrimination between methylated and unmethylated modified sequences.32

DNA was extracted from 26 randomly selected HL cases on the basis of the availability of frozen tissue, and from all the cell lines, using standard phenol-chloroform methods. After extraction, 1 μg DNA was denatured in 3 M NaOH at 42°C for 20 minutes and treated with 520 μL of 4.3 M sodium bisulfite, pH 5.0, in the presence of 30 μL of 20 mM hydroquinone at 50°C for 17 hours. DNA was then purified using the Wizard DNA Clean-Up system (Promega, Madison, WI), treated with 3 M NaOH at 37°C for 20 minutes, precipitated with ammonium acetate and ethanol, and resuspended in 40 μLH2O. As an initial positive control, in vitro–methylated DNA was generated by treatment of 5 μg genomic DNA with 20 U SssI-methylase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and 160 μM S-adenosyl-methionine for 4 hours at 37°C.

Primer sequences for the methylated-specific reaction were 5′-GAT TTC GCG GGG TCG AAT TTC G-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACT AAC GCT CGC GCT CGC AA-3′ (antisense), whereas primer sequences for the unmethylated-specific reaction were 5′-GTT GGT AGG AGG GAG TTG GTG TG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAC CCT CCA CCC TAC TAA CAC TCA CA-3′ (antisense). These primer sets were designed according to previously described criteria32 to amplify 165 and 132 base pairs (bp), respectively, from the region immediately upstream of the first transcription start site, coincidental with a peak of maximum density of CpG sites.

The PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μL. Reaction mixtures contained 1X FastStart PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), 10 pmol of each primer, 1.5 U FastStart Taq polymerase (Roche, Milan, Italy), and 75 ng bisulfite-modified DNA. PCR conditions were as follows: 5 minutes at 95°C, 40 to 42 cycles of amplification (30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 61°C, 30 seconds at 72°C), and 10 minutes at 72°C. All reactions were performed with positive and negative controls for both unmethylated and methylated alleles and a no-DNA control. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Positive results for the MSP reactions were considered in those cell lines or HL cases showing detectable bands in the methylated-specific reaction (M) in at least 2 independent experiments.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing

In the bisulfite sequencing technique, the fragment of interest is amplified from bisulfite-modified DNA, cloned, and sequenced, in order to obtain an accurate map of the distribution of CpG methylation.33

A new primer set (5′-TAG GAA TTG GGG TAG TTG GGG-3′ [sense] and 5′-TTT CCT TCA CTC CCT CCC TTA CTA C-3′ [antisense]) was designed to amplify a region of 483 bp surrounding the first transcription start site that contained 44 CpG dinucleotides. PCR conditions were as follows: 5 minutes at 95°C, 42 cycles of amplification (30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 58°C, 75 seconds at 72°C), and finally 10 minutes at 72°C. The PCR mixture contained 1X FastStart PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 20 pmol of each primer, 2 U FastStart Taq polymerase, and 100 ng bisulfite-modified DNA in a final volume of 50 μL. PCR products were gel purified (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (TOPO-TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Clones containing the desired insert were sequenced in an ABI 3700 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany).

Laser capture microdissection and bisulfite sequencing of RS cells

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) was performed to isolate single cells using a SL-Microtest instrument (MMI, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). Pools of RS cells and normal reactive cells were dissected from 10-μm frozen tissue sections immunostained with a commercial anti-CD30 antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom). Approximately 100 RS (large atypical CD30+) cells and 200 to 300 normal (CD30-) cells were isolated in separate vials. DNA was extracted by overnight digestion with proteinase K at 55°C and ethanol precipitation, and a modified bisulfite treatment was performed according to Millar et al.34

For genomic sequencing on microdissected cells, a 165-bp fragment containing 14 CpG dinucleotides was amplified using a seminested PCR. Primers sequences were as follows: 5′-TAG GAA TTG GGG TAG TTG GGG-3′ (sense); 5′-CCC TCA TTC CC(G/A) CCT CC-3′ (external antisense); 5′-TCC C(G/A)C TCT CCA CCT CCT C-3′ (internal antisense). PCR conditions were as previously published34 with slight modifications. The PCR products were gel-purified, cloned, and sequenced as described in “Bisulfate genomic sequencing.”

Statistical study

For the purpose of statistical analysis, the clinical status of the different patients at diagnosis was defined using the Ann Arbor stage and the International Prognostic Score (IPS).35 The Pearson chi-square test was used where appropriate to establish whether there were any relationships between the clinical characteristics of the patients and IHC results.

Survival analyses were performed on all the classic HL cases for which clinical and follow-up information was available (approximately 70%). Actuarial survival curves, in terms of overall survival (OS), were plotted using the Kaplan and Meier method. Statistical significance of associations between individual variables and OS was determined using the log-rank test. A multivariate Cox model was used to compare the predictive performance with the IPS prediction. All statistical analyses addressing the clinical outcome of the patients were restricted to HIV-negative patients with classical HL.

All tests were 2-sided and P values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant. The SPSS (SPSS, Chicago IL: SPSS; 1999) software package was used for these analyses.

Results

The pattern of expression of p18INK4c protein is abnormal in HL tumor samples, compared with normal lymphoid tissue

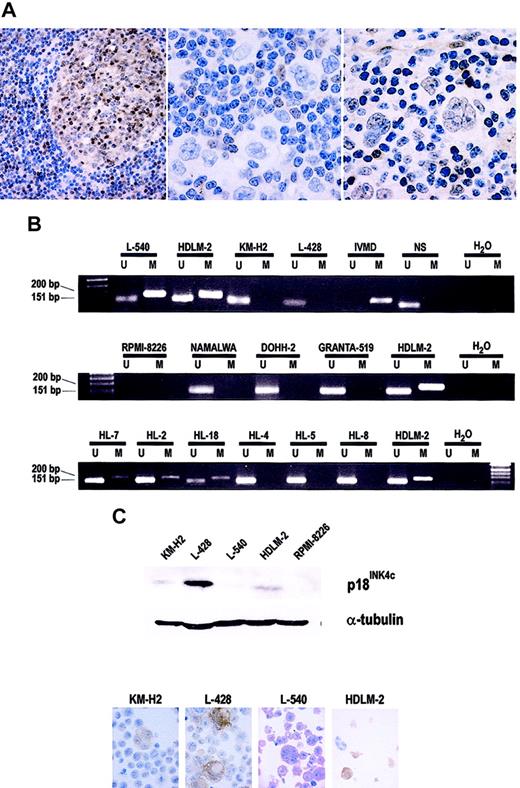

All the samples from reactive lymphoid tissue tested by IHC displayed nuclear (and, to a lesser extent, cytoplasmic) staining by most germinal center lymphocytes (more intensely in mature centrocytes and plasma cells), whereas mantle zone lymphocytes were usually unstained (Figure 1A). The large majority of mature plasma cells in the interfollicular areas was also positive. These differences are consistent with the proposed regulation of p18INK4c protein expression through normal B-cell differentiation.20

Analysis of p18INK4c protein expression and promoter hypermethylation. (A) Immunohistochemical detection of the p18INK4c protein. In reactive lymphoid tissue (left panel: a benign lymph node), p18INK4c is expressed mainly by lymphocytes in germinal centers and interfollicular plasma cells, but not by mantle cells. Middle and right panels: Examples of HL cases showing absence and presence, respectively, of p18INK4c protein expression by RS cells. (B) MSP analysis of the methylation status of the p18INK4c promoter in HL-derived cell lines (top), NHL-derived cell lines (middle), and HL tumors (bottom). IVMD indicates in vitro–methylated DNA; NS, DNA from a sample of normal spleen, used as a negative (unmethylated) control; U, unmethylated; and M, methylated. (C) p18INK4c protein expression in HL-derived cell lines. Top: Western blot analysis of p18INK4c expression in total protein extracts from the HL cell lines. The multiple myeloma cell line RPMI-8226 shows total absence of p18INK4c expression and was included as a negative control. The expression of α-tubulin was analyzed as a loading control. Bottom: Immunohistochemical staining for p18INK4c on cytospin preparations of the HL-derived cell lines. Original magnification × 1000 for all electron microscopy except left panel of A (× 200).

Analysis of p18INK4c protein expression and promoter hypermethylation. (A) Immunohistochemical detection of the p18INK4c protein. In reactive lymphoid tissue (left panel: a benign lymph node), p18INK4c is expressed mainly by lymphocytes in germinal centers and interfollicular plasma cells, but not by mantle cells. Middle and right panels: Examples of HL cases showing absence and presence, respectively, of p18INK4c protein expression by RS cells. (B) MSP analysis of the methylation status of the p18INK4c promoter in HL-derived cell lines (top), NHL-derived cell lines (middle), and HL tumors (bottom). IVMD indicates in vitro–methylated DNA; NS, DNA from a sample of normal spleen, used as a negative (unmethylated) control; U, unmethylated; and M, methylated. (C) p18INK4c protein expression in HL-derived cell lines. Top: Western blot analysis of p18INK4c expression in total protein extracts from the HL cell lines. The multiple myeloma cell line RPMI-8226 shows total absence of p18INK4c expression and was included as a negative control. The expression of α-tubulin was analyzed as a loading control. Bottom: Immunohistochemical staining for p18INK4c on cytospin preparations of the HL-derived cell lines. Original magnification × 1000 for all electron microscopy except left panel of A (× 200).

NHLs recapitulated the differences observed in p18INK4c protein expression in reactive lymphoid tissue: tumors derived from follicular center cells (all the FCL, DLBCL, and BL samples included in the TMAs: 16/20) expressed nuclear reactivity for p18INK4c, whereas all MCL tumors were negative (data not shown).

In contrast, a substantial number of HL samples showed no p18INK4c nuclear staining in the RS cells (143/316 samples, 45.3%; Figure 1A). Samples recorded as p18INK4c-positive always showed a significant amount of positive RS cells, in contrast to the complete absence of tumoral cells with p18INK4c nuclear expression in cases considered as negative. The loss of p18INK4c nuclear expression in the tumoral cells was found in both forms, classical HL (136/306 cases) and nodular lymphocyte–predominant HL (7/10 cases). This observation suggests an abnormal pattern of p18INK4c protein expression, apparently restricted to HL tumors.

p18INK4c gene promoter hypermethylation in HL-derived cell lines

The genomic region containing the promoter and first exon of the p18INK4c gene displays a relatively high density of CpG dinucleotides. Since the most common mechanism of CKI loss in hematologic malignancies is promoter hypermethylation, we investigated by MSP the methylation status of the p18INK4c gene in the HL cell lines and compared it with that of NHL cell lines. We found that KM-H2 and L-428 displayed amplification bands for only the unmethylated reaction, whereas L-540 and HDLM-2 amplified in both the M and U reactions (Figure 1B). Of 7 NHL-derived cell lines, 6 (RAJI, NAMALWA, GRANTA-519, WSU-NHL, KARPAS-422, and DOHH-2) showed only unmethylated bands in the MSP assays (Figure 1B). The multiple myeloma–derived cell line RPMI-8226 failed to amplify either M or U bands, a finding consistent with the previously described sporadic homozygous deletion of the p18INK4c gene in myeloma cell lines.24 The existence of this deletion in RPMI-8226, but not in any of the other cell lines, was confirmed by multiplex PCR using unmodified genomic DNA as a template (data not shown).

As might be expected, this hypermethylated status of the p18INK4c promoter correlated with loss of protein expression as demonstrated by Western blot and IHC (Figure 1C). p18INK4c protein expression was almost completely absent from the L-540 cell line, and clearly reduced in HDLM-2 and KM-H2 compared with the L-428 cell line.

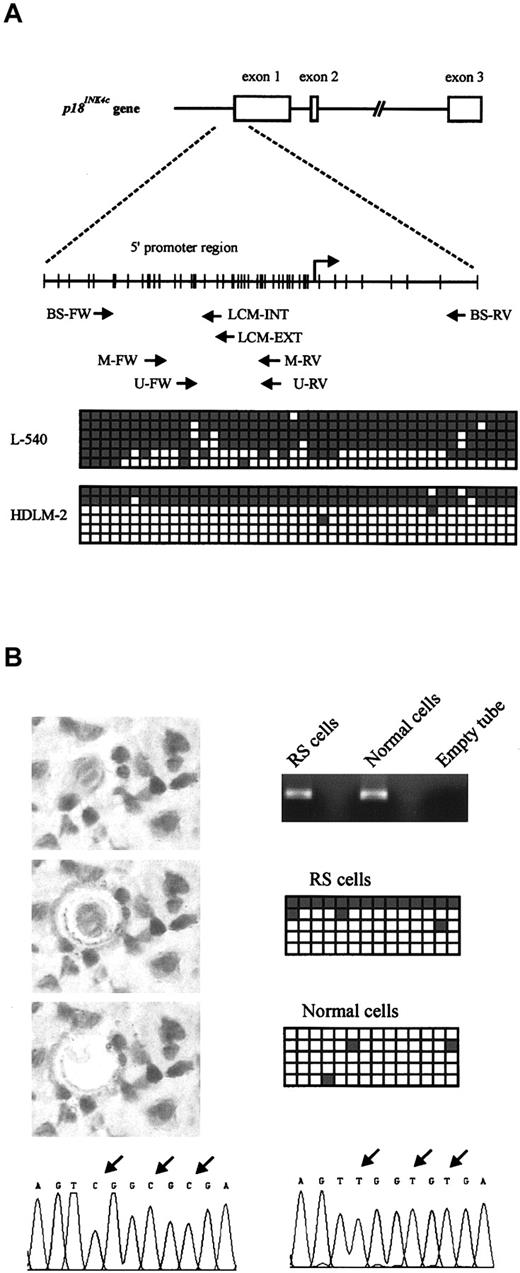

The amplification of U and M bands in some HL-derived cell lines probably reflects interallelic heterogeneity of CpG island methylation. To confirm the methylation-associated silencing of the p18INK4c gene, and to analyze the pattern of CpG island methylation, we performed bisulfite genomic sequencing of a fragment of the promoter region of p18INK4c containing 44 CpG sites (as indicated in Figure 2A) in the L-540 and HDLM-2 cell lines. The L-540 cell line showed a high degree of CpG methylation in most sequenced clones, whereas only 2 clones from HDLM-2 were hypermethylated. These results are consistent with the results obtained by MSP, Western blot, and IHC.

Structure and bisulfite sequencing of the p18INK4c promoter. (A) Top: Genomic structure of the p18INK4c gene. Middle: Distribution of CpG dinucleotides in the promoter region of p18INK4c. Each vertical bar represents a CpG dinucleotide, and the transcription start site is indicated by an arrow. The position of the primer sets used for MSP assays (M-FW, M-RV, U-FW, and U-RV) and bisulfite sequencing (BS-FW and BS-RV for cell lines; BS-FW, LCM-EXT, and LCM-INT for microdissected cells) is also indicated. FW indicates forward; RV, reverse. Bottom: Bisulfite sequencing of the 2 HL-derived cell lines showing p18INK4c promoter hypermethylation (L-540 and HDLM-2). A 483-bp fragment comprising the region immediately upstream of the transcriptional start site and part of exon 1 was amplified and cloned from bisulfite-modified DNA. From each cell line, 6 clones were sequenced. Each row represents 1 clone, and squares represent CpG dinucleotides. Open squares indicate unmethylated CpG sites; gray squares, methylated CpG sites. (B) Bisulfite sequencing of microdissected cell populations. RS and normal cells were isolated by LCM (left). Original magnification × 400. DNA extracted from these cells was treated with sodium bisulfite and used as a template to amplify a 165-bp fragment from thep18INK4c promoter (right), which was cloned and sequenced (5 clones from each reaction are represented as in panel A). Arrows above the electropherograms indicate differences between methylated (bottom, left) and unmethylated (bottom, right) sequences.

Structure and bisulfite sequencing of the p18INK4c promoter. (A) Top: Genomic structure of the p18INK4c gene. Middle: Distribution of CpG dinucleotides in the promoter region of p18INK4c. Each vertical bar represents a CpG dinucleotide, and the transcription start site is indicated by an arrow. The position of the primer sets used for MSP assays (M-FW, M-RV, U-FW, and U-RV) and bisulfite sequencing (BS-FW and BS-RV for cell lines; BS-FW, LCM-EXT, and LCM-INT for microdissected cells) is also indicated. FW indicates forward; RV, reverse. Bottom: Bisulfite sequencing of the 2 HL-derived cell lines showing p18INK4c promoter hypermethylation (L-540 and HDLM-2). A 483-bp fragment comprising the region immediately upstream of the transcriptional start site and part of exon 1 was amplified and cloned from bisulfite-modified DNA. From each cell line, 6 clones were sequenced. Each row represents 1 clone, and squares represent CpG dinucleotides. Open squares indicate unmethylated CpG sites; gray squares, methylated CpG sites. (B) Bisulfite sequencing of microdissected cell populations. RS and normal cells were isolated by LCM (left). Original magnification × 400. DNA extracted from these cells was treated with sodium bisulfite and used as a template to amplify a 165-bp fragment from thep18INK4c promoter (right), which was cloned and sequenced (5 clones from each reaction are represented as in panel A). Arrows above the electropherograms indicate differences between methylated (bottom, left) and unmethylated (bottom, right) sequences.

The expression of p18INK4c protein in RS cells in primary tumors is also abolished by gene promoter hypermethylation

The results obtained in cell lines suggest that this epigenetic silencing of p18INK4c expression may also occur in primary tumors. To determine if the MSP assay was suitable for the detection of small amounts of methylated DNA, such as those probably present in HL samples, a sensitivity study was performed. We were able to consistently detect methylated p18INK4c alleles in dilutions up to 1:1000 (0.1%) of the methylated L-540 cell line in unmethylated DNA (L-428; data not shown).

We analyzed the methylation status of the p18INK4c gene by MSP in DNA extracted from HL-affected tissues. p18INK4c hypermethylation was detected in 19.2% (5/26 of tumoral samples; Figure 1B). As might be expected, all samples also had unmethylated alleles, presumably corresponding to surrounding nonmalignant cells.

Since the loss of p18INK4c protein expression detected by IHC is restricted to the RS cells, we speculated that hypermethylation could most likely be attributed to this tumoral component. To demonstrate that the positive signal in the MSP assay originated from RS cells, we microdissected RS and benign cells from one of the MSP-positive HL cases and performed bisulfite sequencing on DNA isolated from the 2 separate cell populations (Figure 2B). High-density methylation of the analyzed sequence was detected only in DNA from RS cells, although, as in the cell lines, interallelic heterogeneity was observed. None of the analyzed clones from microdissected reactive cells contained hypermethylated DNA.

The comparison with the results for p18INK4c protein expression showed that all hypermethylated cases were negative by IHC (5/5). Cases showing amplification of only U bands by MSP expressed p18INK4c protein in a variable proportion of cases: 9 of 16 cases were p18INK4c-positive and 7 of 16 were negative. These results probably reflect the existence of alternative inactivation mechanisms, but we cannot exclude a number of false-negative results in some HL samples due to the scarcity of RS cells.

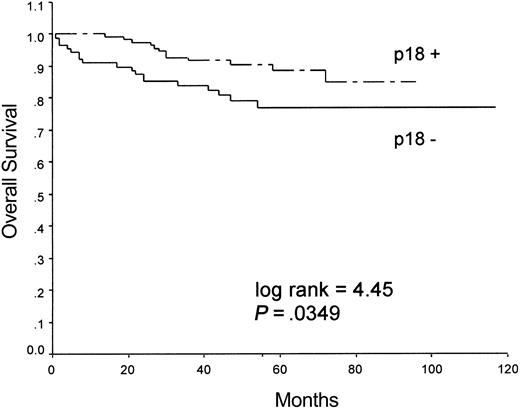

The loss of p18INK4c protein expression in HL tumors is associated with less favorable clinical outcome

To test the clinical relevance of the loss of p18INK4c, we compared some clinical features (stage and IPS) at presentation and follow-up of the HIV-negative, classical HL patients. p18INK4c loss was independent of the clinical presentation and stage at diagnosis, but there was a clear relationship with treatment response, since 61% of p18INK4c-negative cases had a bad treatment response compared with 39% of p18INK4c-positive cases (treatment response was considered unfavorable in patients who either did not achieve complete remission after treatment or had relapsed < 12 months after remission), although the difference just failed to meet the criterion for significance (P = .055).

In agreement with this finding, the 2 groups of p18INK4c-positive and p18INK4c-negative cases had significant differences in the overall survival probability, as indicated by univariate analyses, during the follow-up period (log-rank = 4.45, P = .0349), with the p18INK4c-negative phenotype associated with shorter survival times. Survival curves for the 2 groups are shown in Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with HL grouped according to the expression of p18INK4c.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with HL grouped according to the expression of p18INK4c.

A multivariate Cox model including p18INK4c protein expression in HL tumors and the IPS was fitted (Table 1). The hazard ratios from the multivariate analysis were both significant, thus showing that the prognostic impact of the p18INK4c loss can be regarded as independent of the conventional IPS prognostic system.

Multivariate Cox model including p18INK4c protein expression and IPS

. | B . | SE(B) . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | 1.608 | 0.399 | 4.99 | 2.28-10.92 | .000 |

| p18INK4c | 0.881 | 0.407 | 2.41 | 1.09-5.35 | .030 |

. | B . | SE(B) . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | 1.608 | 0.399 | 4.99 | 2.28-10.92 | .000 |

| p18INK4c | 0.881 | 0.407 | 2.41 | 1.09-5.35 | .030 |

X2 = 24.376; P < .001.

B indicates estimated coefficients; SE(B), standard errors; HR, hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI); and P, P values corresponding to the Wald statistic for each coefficient.

Discussion

HL is a distinct primary lymphoid malignancy, classically associated with an abundance of inflammatory cells that outnumber the recognized tumoral subpopulation of RS cells. Defects in the regulation of the cell cycle, apoptosis, and signaling pathways have been repeatedly demonstrated in these cells.25,31,36 Additionally, the RS cells harbor clonally rearranged and somatically mutated immunoglobulin genes, indicating that they derive from germinal center B cells,37 although they characteristically show a defective B-cell terminal differentiation program.26,27,38

Loss of different CKIs has been demonstrated in HL tumors. Thus, hypermethylation of the 5′ CpG island of the p16INK4a and p15INK4b promoters associated with loss of protein expression seems to constitute a relatively frequent event.8,9 In the majority of cases, p27KIP1 protein is also lost, probably as a consequence of increased degradation mediated by SKP2, a ubiquitin ligase for p27KIP1 that has been found overexpressed in RS cells in most HL cases.25 Absence of p21WAF1 protein expression is detected in only a fraction of cases.25

In addition to these well-characterized alterations in this tumoral model, here we demonstrate a p18INK4c transcriptional repression associated with promoter hypermethylation in some HL-derived cell lines and primary tumors. This finding in human tumors is comparable to previous observations in mouse models,14,15,39 suggesting that p18INK4c functions as a tumor suppressor gene. Although pituitary tumors are the main finding in p18INK4c-null mice, a higher proliferative rate upon mitogenic stimulation of B and T lymphocytes and the development of lymphoproliferative disorders including B-cell and T-cell lymphomas have also been demonstrated in these models.14,40

In addition to the frequent loss of CKIs, among them p18INK4c, the tumoral RS cells are also characterized by the increased expression in a large proportion of cases of cyclins and CDKs involved in G1/S and G2/M transitions, such as cyclin D, cyclin A, cyclin B1, cyclin E, CDK2, and CDK6,25,31 which differs from the observations in reactive lymphoid tissue and other NHLs. Since the activation of CDK6 may induce the transcription of p18INK4c via E2F-1 activation,41 the simultaneous overexpression of CDK6 and p18INK4c inactivation suggest that the loss of this autoregulatory mechanism may be important in these tumors.

Cell cycle arrest is tightly coupled to terminal differentiation of late-stage B cells. Thus, p18INK4c inhibition of CDK6 plays a pivotal role in integrating cell cycle arrest with terminal (plasma cell) differentiation.19,20 The p18INK4c requirement in terminal B-cell differentiation is specific, since p18INK4c deficiency cannot be compensated by other CKIs in vivo, including p19INK4d, p21WAF1, or p27KIP1.20 This link between cell cycle control and terminal differentiation may, at least in part, be related to the defective B-cell differentiation state characteristic of RS cells.26,27,38

The pathogenic relevance of p18INK4c in HL is additionally strengthened by the clearly established clinical relevance to the outcome of HL patients. HIV-negative, classical HL cases featuring loss of p18INK4c protein expression behave significantly worse than p18INK4c-positive cases, display poorer treatment response (lower probability of having sustained complete remission), and show inferior survival. Moreover, the loss of p18INK4c is independent of the clinical stage or clinical extension of the tumors at diagnosis and predicts survival independently of the IPS. It is noteworthy that previous reports failed to demonstrate clear relationships between inactivation of other CKIs and the clinical outcome in HL patients,25 highlighting the biologic relevance of p18INK4c in this specific tumor. However, further studies are needed to clarify these relationships and the exact role of p18INK4c silencing in HL and other tumors, and to investigate the CKI alterations present in p18INK4c-positive cases.

In summary, our results demonstrate a common p18INK4c transcriptional repression due to promoter hypermethylation in HL tumors and HL-derived cell lines. This is the first report of p18INK4c silencing in human tumors due to epigenetic mechanisms, adding p18INK4c to the long list of tumor suppressor genes whose expression can be silenced through promoter methylation. The combination of this and other defects in the cell cycle could not only be related with abnormal cell cycle regulation, but it also seems to couple the abnormalities in cell cycle with defective B-cell differentiation in RS cells.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 26, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2356.

Supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS PI020323 and G03/179) and the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (SAF2001-0060), Spain. A.S.-A. is supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid, Spain, and the European Social Fund. F.I.C. is supported by a grant from the Madrid City Council and the CNIO.

A.S.-A. and J.D. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are indebted to Laura Cereceda (CNIO Tumor Bank) for her excellent assistance with data management, and to María J. Acuña, Ana Díez, and Raquel Pajares for their expertise and excellent technical assistance with TMA technology and immunohistochemical assays. We also thank all the participating members of the Spanish Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group for their collaboration in collecting samples and clinical data.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal