Abstract

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) evolves from a chronic phase characterized by the Philadelphia chromosome as the sole genetic abnormality into blast crisis, which is often associated with additional chromosomal and molecular secondary changes. Although the pathogenic effects of most CML blast crisis secondary changes are still poorly understood, ample evidence suggests that the phenotype of CML blast crisis cells (enhanced proliferation and survival, differentiation arrest) depends on cooperation of BCR/ABL with genes dysregulated during disease progression. Most genetic abnormalities of CML blast crisis have a direct or indirect effect on p53 or Rb (or both) gene activity, which are primarily required for cell proliferation and survival, but not differentiation. Thus, the differentiation arrest of CML blast crisis cells is a secondary consequence of these abnormalities or is caused by dysregulation of differentiation-regulatory genes (ie, C/EBPα). Validation of the critical role of certain secondary changes (ie, loss of p53 or C/EBPα function) in murine models of CML blast crisis and in in vitro assays of BCR/ABL transformation of human hematopoietic progenitors might lead to the development of novel therapies based on targeting BCR/ABL and inhibiting or restoring the gene activity gained or lost during disease progression (ie, p53 or C/EBPα).

Introduction

Blast crisis is the terminal phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), a clonal myeloproliferative disorder of the hematopoietic stem cell that typically evolves in 3 distinct clinical stages: chronic and accelerated phases and blast crisis.1,2 The chronic phase lasts several years and is characterized by accumulation of myeloid precursors and mature cells in bone marrow, peripheral blood, and extramedullary sites.1,2 The accelerated phase lasts 4 to 6 months and is characterized by an increase in disease burden and in the frequency of progenitor/precursor cells rather than terminally differentiated cells. The blast crisis lasts only a few months and is characterized by the rapid expansion of a population of myeloid or lymphoid differentiation-arrested blast cells.3 CML is consistently associated with an acquired genetic abnormality, the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph1), a shortened chromosome 22 resulting from a reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22.4,5 This translocation generates the BCR/ABL fusion gene, which is translated in the p210BCR/ABL oncoprotein6,7 of almost all patients with CML.

Two other BCR/ABL proteins, p190 and p230, generated by variant fusion genes, are only occasionally detected in classic CML.8 Expression of p210BCR/ABL is necessary and sufficient for malignant transformation, as demonstrated in in vitro assays and leukemogenesis in mice.9-13 Transition to blast crisis is the unavoidable outcome of CML except in a cohort of patients receiving allogeneic bone marrow transplants early in the chronic phase.14 The development of the BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; formerly STI571; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) as the treatment of choice for chronic-phase CML and its remarkable therapeutic effects suggest that blast crisis transition will be postponed for several years in most patients with CML.15,16 However, the persistence of BCR/ABL transcripts in a cohort of patients with complete cytogenetic response raises the possibility that treatment with imatinib mesylate alone might not prevent disease progression.17

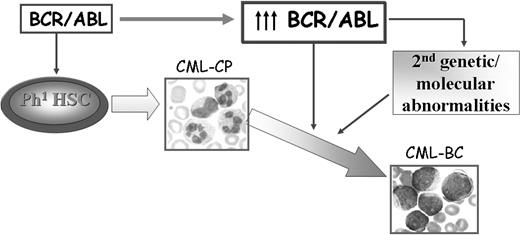

The mechanisms responsible for transition of CML chronic phase into blast crisis remain poorly understood, although a reasonable assumption is that the unrestrained activity of BCR/ABL in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells is the primary determinant of disease progression. No causal relationship has been demonstrated yet between BCR/ABL expression, which specifically increases during disease progression18,19 in hematopoietic stem cells and committed myeloid progenitors,20 and the secondary genetic changes of CML blast crisis (CML-BC). However, a plausible model of disease progression predicts that increased BCR/ABL expression promotes the secondary molecular and chromosomal changes essential for the expansion of cell clones with increasingly malignant characteristics and remains crucial for the malignant phenotype even in advanced stages of the disease (Figure 1).

Possible mechanisms of CML disease progression. BCR/ABL expression is sufficient to transform hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and to induce a CML-like disorder in mice. Increased expression of BCR/ABL, frequently observed in patients with CML-BC, might promote secondary molecular and genetic abnormalities that contribute to the expansion of a cell population characterized by enhanced proliferation, increased resistance to apoptosis, and differentiation arrest.

Possible mechanisms of CML disease progression. BCR/ABL expression is sufficient to transform hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and to induce a CML-like disorder in mice. Increased expression of BCR/ABL, frequently observed in patients with CML-BC, might promote secondary molecular and genetic abnormalities that contribute to the expansion of a cell population characterized by enhanced proliferation, increased resistance to apoptosis, and differentiation arrest.

According to this model, CML-BC would be expected to occur only in patients presenting with disease resistant to imatinib mesylate or in those developing resistance during treatment. Although there is no indication yet that patients resistant to imatinib mesylate have a clinically distinct disease, it is possible that they will present distinct genetic abnormalities, the appearance of which could be influenced by the duration of BCR/ABL-dependent signals. Thus, the biology of CML-BC in the years before imatinib mesylate and in the imatinib mesylate era may be different. With this in mind, we will illustrate the molecular mechanisms underlying transition to CML-BC according to a model of disease progression in which (1) BCR/ABL activity is necessary for the accumulation of secondary genetic abnormalities or changes in gene expression or both, and (2) such secondary events directly or indirectly promote differentiation arrest, the distinctive feature of CML-BC.

Effects of BCR/ABL on proliferation and survival of myeloid progenitor cells

In hematopoietic CML cells carrying the Ph1 chromosome, the BCR/ABL fusion gene encodes p210BCR/ABL, an oncoprotein, which, unlike the normal p145 c-Abl, has constitutive tyrosine kinase activity21 and is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm.22 The tyrosine kinase activity is essential for cell transformation23 and the cytoplasmic localization of BCR/ABL allows the assembly of phosphorylated substrates in multiprotein complexes that transmit mitogenic and antiapoptotic signals.24

Ectopic expression of p210BCR/ABL results in growth factor independence and leukemic transformation of immortal hematopoietic cell lines.10,24,25 Transplantation of BCR/ABL-transduced hematopoietic stem cells or transgenic expression of p210BCR/ABL induces leukemia and myeloproliferative disorders, indicating a direct, causal role of BCR/ABL in CML.11-13 However, most in vitro studies have relied on the use of growth factor–dependent hematopoietic cell lines, whereas most in vivo studies have used BCR/ABL genes linked to strong promoters. Despite the ample literature on the mechanisms of BCR/ABL-induced transformation, the paucity of data in human hematopoietic progenitors and the limitations of the existing murine models leave many open questions regarding the relevant effects of BCR/ABL in hematopoietic cells.

Ectopic expression of BCR/ABL in growth factor–dependent cell lines activates numerous signal transduction pathways responsible for growth factor independence and reduced susceptibility to apoptosis of these cells (Figure 2).

Schematic representation of the main BCR/ABL-activated pathways regulating proliferation and survival of BCR/ABL-transformed hematopoietic cells.

Schematic representation of the main BCR/ABL-activated pathways regulating proliferation and survival of BCR/ABL-transformed hematopoietic cells.

RAS pathway

The RAS pathway becomes constitutively activated by alternative mechanisms involving the interaction of BCR/ABL with the growth factor receptor-binding protein (GRB-2)/Gab2 complex, via the GRB-2–binding site in the BCR portion of BCR/ABL, and the recruitment/phosphorylation of the SHC adaptor.26,27

The interaction of BCR/ABL with GRB-2/Gab2 and the phosphorylation of SHC lead to enhanced activity of the guanosine diphosphate/guanosine triphosphate (GDP/GTP) exchange factor SOS, which promotes the accumulation of the active GTP-bound form of RAS (Figure 2). The importance of RAS-dependent signaling for the phenotype of BCR/ABL-expressing cells is supported by the observation that down-regulation of this pathway by antisense strategies, expression of dominant-negative molecules, or chemical inhibitors suppresses proliferation and sensitizes cells to apoptotic stimuli.28-30 However, it remains unclear whether primary CML cells express increased levels of the GTP-bound, active form of RAS.

PI-3K/Akt pathway

The phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3K) is another important pathway activated by ectopic expression of oncogenic Abl proteins.31,32 BCR/ABL interacts indirectly with the p85 regulatory subunit of PI-3K33 via various docking proteins including GRB-2/Gab2 and c-cbl27,34 (Figure 2). PI-3K activation via the GRB-2/Gab2 interaction appears pathologically relevant because Gab2-deficient marrow cells are resistant to BCR/ABL transformation.27

Activation of the PI-3K pathway triggers an Akt-dependent cascade that has a critical role in BCR/ABL transformation35 by regulating the subcellular localization or activity of several targets such as BAD, MDM2, IκB-kinase-α, and members of the Forkhead family of transcription factors36 (Figure 2). Phosphorylation of BAD suppresses its proapoptotic activity because, when phosphorylated, BAD is sequestered in the cytoplasm in a complex with 14-3-3β.37 In BCR/ABL-expressing cells, BAD is cytoplasmic and heavily phosphorylated.38 Ectopic expression of a mutant form of BAD, which cannot be phosphorylated by Akt, induces massive apoptosis,38 suggesting that inactivation of BAD proapoptotic effects is important for survival of BCR/ABL-expressing cells. Phosphorylation of MDM2 enhances its nucleus-cytoplasm export, potentially inducing a more efficient degradation of p53.39,40 Phosphorylation of the IκB-kinase-α enhances its activity toward IκB, its substrate.41 On phosphorylation, IκB is subjected to ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation, allowing the translocation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) into the nucleus where it functions as a transcription factor.42 Thus, the net effect of IκB-kinase-α phosphorylation is enhanced NF-κB activity, which has been associated with BCR/ABL-dependent transformation of primary mouse marrow cells.43

Phosphorylation of the transcription factor FKHRL1 prevents its translocation into the nucleus and the transactivation of genes promoting apoptosis (ie, TRAIL) or inhibiting cell cycle progression (ie, p27).44-46

The PI-3K/Akt pathway is also involved in down-modulating the expression or the function of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p27.47-49 Akt directly phosphorylates p27 and prevents its nuclear translocation50-52 ; activated mutants of Akt induce down-regulation of p27, which is prevented by proteasome inhibitors, suggesting that Akt modulates p27 stability.47 It is unclear whether phosphorylation by Akt leads to p27 degradation or whether other Akt-dependent mechanisms are involved in this process. Regardless of the mechanisms, BCR/ABL-activated Akt may enhance the proliferative potential of BCR/ABL-expressing cells by disruption of p27 activity.

Consistent with the effects of Akt on such a variety of targets, inhibition of the PI-3K/Akt pathway suppresses in vitro colony formation and in vivo leukemogenesis of BCR/ABL-expressing cells,32,35 and marrow cells defective in PI-3K/Akt activation are resistant to BCR/ABL transformation.27 Moreover, some evidence also indicates that the PI-3K/Akt pathway is constitutively active in primary CML cells.32

STAT5 pathway

Another antiapoptotic pathway activated by BCR/ABL is that dependent on signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5).53-56 STAT5 is activated by BCR/ABL via the Src family hematopoietic cell kinase (HcK).57 On interaction with the SH3 and SH2 domains of BCR/ABL, this kinase is activated and phosphorylates tyrosine 699 of STAT5B, leading to its translocation to the nucleus where it functions as a transcription factor57 (Figure 2). The importance of STAT5 in BCR/ABL leukemogenesis is supported by the following observations: (1) BCR/ABL mutants defective in STAT5 activation were less efficient than the wild-type form in transformation of 32Dcl3 myeloid precursor cells58 ; (2) a constitutively active STAT5 mutant rescued the leukemogenic potential of STAT5 activation-deficient BCR/ABL mutants58 ; and (3) ectopic expression of a dominant-negative STAT5 mutant suppressed BCR/ABL-dependent transformation of primary mouse marrow cells.58 The role of STAT5 in BCR/ABL leukemogenesis is likely to depend on transcriptional activation of its target genes. A STAT5 target gene potentially involved in BCR/ABL leukemogenesis is the antiapoptotic Bcl-XL gene.59 A causal relationship between Bcl-XL expression and the reduced susceptibility to apoptosis of BCR/ABL-expressing cells has not been demonstrated; however, the rapid down-modulation of Bcl-XL levels in imatinib mesylatetreated BCR/ABL-expressing cells59 and the requirement of Bcl-XL for cytokine-dependent antiapoptotic signals60 are consistent with a critical role of Bcl-XL in the apoptosis resistance of BCR/ABL-expressing cells. The activation of 2 other STAT5 targets, A1 and pim1, may be also involved in BCR/ABL leukemogenesis as indicated by the improved survival of mice injected with marrow cells coexpressing BCR/ABL, kinase-deficient pim1 and A1 antisense transcripts.61 Together, these data point to the importance of STAT5 activation in BCR/ABL-dependent transformation, but need to be reconciled with the findings of Sexl et al who used a genetic approach to demonstrate that the absence of STAT5 expression does not prevent BCR/ABL transformation of murine myeloid cells.62 Perhaps, the acute down-regulation of STAT5 activity obtained on ectopic expression of dominant-negative molecules precludes the BCR/ABL-dependent activation of STAT5 targets that may, instead, occur in STAT5-deficient cells by use of alternative pathways. Although 2 STAT5-target genes, CIS and OSM, were not expressed by STAT5-deficient cells,62 it was not tested whether certain STAT5 target genes potentially involved in transformation (ie, Bcl-XL, A1, pim) were activated by BCR/ABL in a STAT5-independent manner, possibly participating in the process of transformation. Evidence also indicates that STAT5 is constitutively active in CML primary samples, both in chronic phase and in blast crisis.63,64

Although most of the data on the antiapoptotic pathways regulated by BCR/ABL have been obtained in established cell lines and may not entirely apply to primary CML cells, it is likely that most, if not all, of these pathways are less efficiently activated in primary CML cells (perhaps as consequence of reduced BCR/ABL levels), but are still involved in their enhanced survival. A causal relationship between BCR/ABL expression and growth factor-independent survival of CML myeloid progenitors and granulocytes has been demonstrated by an antisense approach.65 In that study, proliferative potential and growth factor response of CML progenitors were also tested, but these progenitors were apparently functionally undistinguishable from their normal counterparts.65

Cell cycle regulation by BCR/ABL

The precise effects of BCR/ABL on proliferation of CML progenitors remain unclear; reports of higher than normal frequency of actively cycling progenitors66,67 coexist with studies that failed to find increased cell proliferation rates in CML.68,69 Highly purified subsets of CML progenitors (CD34+ CD38- cells) survive and proliferate in vitro in the absence of exogenous growth factors, whereas their normal counterparts die rapidly under the same conditions.70 By contrast, the CD34- subset appears to lack the capacity for autonomous growth in vitro.71 These data support a model in which expansion of myeloid progenitors is caused by p210bcr/abl expression/activity in stem cells or primitive progenitors; these cells would normally remain quiescent, but BCR/ABL may promote both symmetrical (to maintain the pool of stem cells) and asymmetrical cell divisions (to generate committed late progenitors).72 Primitive CML progenitors appear to have a greater proportion of cycling cells than normal progenitors, whereas the more abundant, committed CML progenitors might even have a lower proliferative potential of their normal counterpart.72

At the molecular level, exit from quiescence induced by BCR/ABL in primitive progenitor cells might depend on its effect on cyclins and Cdk inhibitors. For example, cyclin D2 levels are increased in BCR/ABL-expressing lymphoblasts73 and are required for stimulation of proliferation induced by BCR/ABL in these cells,74 and down-regulation or cytoplasmic relocation of p27 has been demonstrated in mouse and human lymphoid and myeloid BCR/ABL-expressing cells.74,75 In light of the role of the p21 and p27 Cdk inhibitor in maintaining quiescence and regulating the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells and early progenitors,76,77 the ability of BCR/ABL to modulate levels of cyclin and Cdk inhibitors may be the critical mechanism promoting cell cycle entry of primitive hematopoietic cells. Autocrine production of interleukin 3 (IL-3) by primitive Ph1 CML progenitors has been also proposed as a mechanism leading to the initial expansion of these cells78 and would, in turn, increase cyclin D2 and down-regulate p27 levels, possibly allowing CML primitive progenitors to leave quiescence and start cycling.

A possible explanation for the different effects induced by endogenous BCR/ABL in the CD34+ and CD34- subset may rest in its levels of expression; low levels of BCR/ABL expression typically found in most CML cells may be sufficient for antiapoptotic, but not for proliferative signals, whereas higher levels of BCR/ABL expression in the more primitive subsets of CD34+ cells may be sufficient for both antiapoptotic and proliferative signals.

In summary, the molecular signature of BCR/ABL-expressing cells is consistent with the phenotype of these cells and implicates reduced apoptosis susceptibility and enhanced proliferative potential of specific cell subsets in disease progression.

Effect of BCR/ABL on DNA repair

The transition of CML from chronic phase to blast crisis is characterized by the accumulation of molecular and chromosomal abnormalities,79 but the molecular mechanisms underlying this genetic instability are poorly understood. In the past 2 to 3 years, few studies have directly addressed the relationship between BCR/ABL expression and levels/activity of proteins involved in DNA repair, particularly the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs).

In the first study investigating such a relationship, Deutsch et al80 looked at the effects of BCR/ABL on the catalytic subunit, DNA-PKCS, of the DNA-PK complex formed with the heterodimeric Ku protein. The heterodimeric Ku protein consists of the Ku86 and Ku70 subunits and binds in a sequence-nonspecific manner to double-stranded DNA ends including 5′ and 3′ overhangs, blunt ends, duplex DNA ending in stem-loop structures, and telomers.81 The binding of Ku to free DNA ends recruits and activates DNA-PKCS,82,83 which, in turn, recruits a nuclease, Artemis, to help trim damaged DNA ends.84 Ultimately, the rejoining of the DNA DSBs, requires the recruitment of XRCC4, an accessory factor for DNA ligase IV, and DNA ligase IV itself,85 the enzyme responsible for resealing the DNA strands at the site of the DSBs.86

Repair of DSBs by the DNA-PK–dependent pathway (nonhomologous end-joining recombination) is very important because this is the preferred pathway used by human cells.87

In mice, nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) deficiency accelerates lymphoma formation and promotes the development of soft tissue sarcomas that possess clonal amplifications, deletions, and translocations.88,89 In BCR/ABL-expressing cells (including primary CML cells), levels of DNA-PKCS were markedly down-regulated80 and were reversed by proteasome inhibitors, suggesting the activation of a BCR/ABL-dependent pathway leading to enhanced proteasome-dependent protein degradation.80 Down-regulation of DNA-PKCS levels was associated with a higher frequency of chromosomal abnormalities after exposure of BCR/ABL-expressing cells to ionizing radiation (IR) and increased radiosensitivity.80 Such an increase was, however, modest probably due to enhanced survival of BCR/ABL-expressing cells caused by the activation of multiple antiapoptotic pathways.

The same group also reported an association of BCR/ABL expression in primary CML samples and in established cell lines with down-regulation of BRCA-1,90 a protein involved in the surveillance of genome integrity.91,92 Down-regulation of BRCA-1 was more evident in cell lines in which levels of BCR/ABL were more abundant and was correlated with an increased rate of sister chromatid exchange and chromosome aberration after DNA damage. The limitation of these studies is that they have not been yet confirmed in a large cohort of primary samples obtained from patients with CML and that a causal link between decreased repair of DSBs and disease progression has not been demonstrated. The availability of embryonic and somatic cells with targeted disruption of several genes required for the NHEJ repair of DSBs makes possible the development of mouse models in which to investigate whether defects in this pathway of DNA repair are relevant for BCR/ABL leukemogenesis and disease progression.

Another group identified BCR/ABL-dependent pathways leading to enhanced expression/activity of RAD51,93 a protein that participates in homologous recombination repair (HRR).94 Expression of BCR/ABL increased the efficiency of HRR in a RAD51-dependent manner, as well as resistance to apoptosis induced by drugs like mitomycin C and cisplatin, which promote DSBs.93 In light of enhanced high-fidelity HRR promoted by RAD51,94 it seems counterintuitive that the increased expression/activity of RAD51 (and other paralogues) in BCR/ABL-expressing cells might be associated with genomic instability. Yet, such an increase may result in undesired effects such as a higher frequency of intrachromosomal or interchromosomal deletions and chromosomal translocations dependent on recombination between highly homologous members of the Alu sequence repeat family.95,96 HRR-dependent mechanisms have been also associated with loss of heterozygosity by gene conversion mechanisms and with promotion of small mutations or insertions.96

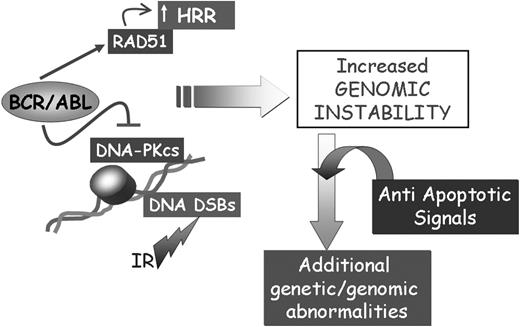

Together, the apparently opposite effects of BCR/ABL on RAD51, DNA-PKCS, and BRCA-1 may not be mutually exclusive and may all be involved in promoting genomic instability associated with defective repair of DSBs (Figure 3). Dysregulation of the DNA repair mechanisms and the acquisition of mutations in genes critically important for the regulation of proliferation is expected to activate control checkpoints (ie, p53 expression), which may lead to the elimination of cells with damaged DNA. However, the ability of BCR/ABL to regulate multiple antiapoptotic pathways, perhaps in a dose-dependent manner and in specific subsets of progenitor cells, is likely to allow survival of cell populations carrying mutations that promote their proliferation and maintenance (Figure 3).

Effect of BCR/ABL on the repair of DSBs. The concomitant effect of BCR/ABL on cell survival and the repair of DSBs might lead to the acquisition of secondary genetic abnormalities contributing to CML disease progression.

Effect of BCR/ABL on the repair of DSBs. The concomitant effect of BCR/ABL on cell survival and the repair of DSBs might lead to the acquisition of secondary genetic abnormalities contributing to CML disease progression.

Mechanisms of disease progression

Mouse models

Although the BCR/ABL oncoprotein plays a central role in the pathogenesis of chronic-phase CML and its continued expression/activity remains important for maintenance of leukemia in mice97 and for proliferation or survival of blast crisis cells in humans,98 the molecular events responsible for the evolution to blast crisis remain unclear. CML–accelerated phase (CML-AP) and CML-BC are characterized by the appearance of various molecular and chromosomal alterations,3 and disease models have been generated to mimic simultaneously the effect of BCR/ABL and of a specific secondary genetic abnormality. This approach has allowed investigators to establish a correlation between disease phenotype and the presence of certain genetic abnormalities, but true models of disease progression are yet to be generated because secondary genetic abnormalities develop in CML only after a long latency. The most common model of BCR/ABL-induced disease relies on transplantation of primary marrow cells isolated from mice treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and transduced with a BCR/ABL retrovirus.99 Transduced cells express BCR/ABL at high levels and induce a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder, which precludes assessment of mechanisms of disease progression.

The leukemogenic potential of the BCR/ABL gene was first tested in transgenic mice using the p190 and p210 BCR/ABL cDNA driven by the metallothionein (MT) enhancer/promoter. MT/p190bcr/abl transgenic lines developed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) with an infiltration of hematopoietic organs by pre-B lymphoblasts,13,100,101 whereas MT/p210bcr/abl transgenic mice developed leukemia with a B- or T-cell, or much less frequently, a myeloid phenotype after a latency of 8 to 44 weeks101,102 (Table 1).

Principal transgenic/“knockin” models of BCR/ABL leukemogenesis

Promoter . | BCR/ABL oncogene . | Disease phenotype . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| MT | p190 | B-ALL/lymphoma | Voncken et al13,101 ; |

| Heisterkamp et al100 | |||

| MT | p210 b3/a2 | T-ALL; B-ALL; myeloblastic leukemia | Voncken et al101 ; |

| Honda et al102 | |||

| Tec | p210 b3/a2 | T-ALL; CML-like | Honda et al103 |

| MMTV-tTA + tet-p210 | p210 b3/a2 | B-ALL | Huettner et al97 |

| CD34-tTA + tet-p210 | p210 b3/a2 | CML-like; thrombocytosis | Huettner et al104 |

| Endogeneous bcr | p190 | B-ALL | Castellanos et al106 |

Promoter . | BCR/ABL oncogene . | Disease phenotype . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| MT | p190 | B-ALL/lymphoma | Voncken et al13,101 ; |

| Heisterkamp et al100 | |||

| MT | p210 b3/a2 | T-ALL; B-ALL; myeloblastic leukemia | Voncken et al101 ; |

| Honda et al102 | |||

| Tec | p210 b3/a2 | T-ALL; CML-like | Honda et al103 |

| MMTV-tTA + tet-p210 | p210 b3/a2 | B-ALL | Huettner et al97 |

| CD34-tTA + tet-p210 | p210 b3/a2 | CML-like; thrombocytosis | Huettner et al104 |

| Endogeneous bcr | p190 | B-ALL | Castellanos et al106 |

Transgenic mice were also generated using the p210bcr/abl cDNA under the control of the Tec promoter103 (Table 1). The Tec gene encodes a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase involved in the control of survival and differentiation fate in immune cells and hematopoietic progenitors of the myeloid and megakaryocyte series. Two of the founder Tec/p210bcr/abl transgenic mice showed excessive proliferation of lymphoblasts shortly after birth and died of leukemia after 3 and 4 months with thymic enlargement, marked splenomegaly, and lymph node swelling. Surface marker analysis of leukemic cells was diagnostic of T-cell leukemia. The progeny of one of these founders revealed a myeloproliferative disorder ensuing at 4 to 8 months after birth and characterized by an increase in megakaryocytes (and platelets) and mature granulocytes and severe anemia, which may have contributed to death of the mice. Mice were usually dead 1 year after birth with marked splenomegaly.

Models of BCR/ABL leukemogenesis have been also obtained by inducible transgenic expression. Using a tetracycline regulatable system in which p210bcr/abl expression was induced in the absence of tetracycline by the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter-driven Tet transactivator, compound transgenic mice developed a B cell-type ALL within 8 to 24 days97 (Table 1). As indicated, this leukemia was highly dependent on continuous BCR/ABL expression.97

Using an inducible model in which p210bcr/abl expression was under the control of human CD34 regulatory elements, the same group showed that transgenic mice all died within 2 to 14 months and the predominant features were chronic thrombocytosis, a marked increase of megakaryocytes in bone marrow and spleen, and the development of splenomegaly accompanied by lymphadenopathy in some mice104 (Table 1).

Altogether, it is clear that the available mouse models of BCR/ABL-induced diseases do not closely mimic CML in humans and that a better understanding of mechanisms of disease progression will require the generation of other transgenic lines (besides the CD34-p210bcr/abl model) in which BCR/ABL-expression is under the control of promoters active only in primitive hematopoietic progenitors.

Additional mouse models of BCR/ABL leukemogenesis could be generated based on pioneering work of Rabbitts and collaborators, who used homologous recombination to target the MLL-AF9 human gene of the t(9;11) translocation to the MLL gene locus105 ; such “knockin” strategy led to the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in chimeric mice.105

This approach was used to fuse p190bcr/abl coding sequences into the endogenous bcr gene.106 By 4 months of age, 95% of chimeric mice expressing one p190bcr/abl allele developed pre-B-ALL106 (Table 1). Because no information is available on the use of this “knockin” strategy to target p210bcr/abl at the bcr locus, it is likely that bcr-regulated expression of p210bcr/abl is toxic for embryonal cells.107 In this regard, the “knockin” approach to generate alleles mimicking the translocation fusion genes was combined with Cre-mediated recombination to prevent the toxic effects for embryonal cells of the AML1-ETO fusion protein of the t(8;21) translocation.108 Activation of AML1-ETO expression resulted in the expansion of myeloid progenitors, but neither blocked differentiation nor promoted leukemia development.108 Treatment of these mice with a single mutagenic dose of the DNA alkylating agent N-ethyl-N-nitroso-urea induced hematopoietic neoplasms 2 to 10 months after treatment.108

These genetic approaches have been elegantly used to obtain a de novo translocation in mice mimicking the t(11;19) that generates the MLL-ENL fusion gene.109 As in humans, the chromosomal translocation between the mouse MLL and ENL genes resulted in the rapid development of leukemia.109

The establishment of disease models of BCR/ABL-induced leukemia with a long myeloproliferative phase would be necessary for assessing mechanisms of disease progression. A highly reproducible model of leukemia is that dependent on transgenic expression of promyelocytic leukemia–retinoic acid receptor α (PML-RARα) under the control of the myeloid precursor-specific cathepsin G promoter.110 This fusion protein causes a myeloproliferative disease in 100% of mice, with only 15% to 20% developing acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) after a latency of 6 to 13 months. Coexpression of the reciprocal RARα-PML fusion protein on crossing cathepsin G-PML-RARα and cathepsin G-RAR α-PML transgenic mice, increased the frequency of APL (55%-60%), but did not shorten latency.110 This model of long-lasting myeloproliferative disorder, which culminates in APL, was used to identify acquired, nonrandom chromosomal abnormalities associated with the development of APL.111 It would be highly beneficial to obtain a BCR/ABL-dependent myeloproliferative disorder in which a relatively long latency precedes the emergence of leukemic clones characteristic of CML-BC. This model could be used to test whether BCR/ABL expression promotes a pattern of genetic changes analogous to that seen in CML-AP/BC patients, the order in which these changes appear, and the consequences of blocking or restoring their effects.

Genetic events

Cytogenetic and molecular changes occur in the vast majority of CML patients during evolution to blast crisis (Table 2). Thus, a recurring question has been whether p210bcr/abl induces genomic instability directly or increasingly frequent genetic abnormalities during disease progression are acquired secondarily. Also, neither situation excludes that genetic instability of CML-BC depends both on increased propensity of BCR/ABL-expressing cells to undergo genetic changes and the probability that one of the mutations induced by BCR/ABL functions as an “amplifier” of a genetically unstable phenotype.

Secondary genetic and molecular abnormalities in CML-BC

Abnormality . | Patients with abnormality, % . |

|---|---|

| Genetic | |

| Double Ph1 chromosome | 38 |

| Trisomy chromosome 8 | 38 |

| i(17q) | 20 |

| Trisomy chromosome 19 | 13 |

| t(3;21)(q26;q22) | 2 |

| t(7;11)(p15;p15) | < 1 |

| Molecular | |

| p53 mutations | 25-30* |

| p16/ARF mutations | 50† |

| Rb mutation/deletion | 18‡ |

| RAS mutation | Rare |

Abnormality . | Patients with abnormality, % . |

|---|---|

| Genetic | |

| Double Ph1 chromosome | 38 |

| Trisomy chromosome 8 | 38 |

| i(17q) | 20 |

| Trisomy chromosome 19 | 13 |

| t(3;21)(q26;q22) | 2 |

| t(7;11)(p15;p15) | < 1 |

| Molecular | |

| p53 mutations | 25-30* |

| p16/ARF mutations | 50† |

| Rb mutation/deletion | 18‡ |

| RAS mutation | Rare |

Abnormalities to watch in the post-imatinib mesylate era include BCR/ABL mutations and BCR/ABL amplifications.

Occurred in 30% of myeloid blas crisis cases

Occurred in 50% of lymphoid blast crisis cases

Occurred in 18% of lymphoid blast crisis cases

Although it is believed that the persistent expression of BCR/ABL, per se, leads to genomic instability, there is also a cohort of patients with CML (10%-15%) presenting with deletions of the derivative chromosome 9 which, ab initio, may be more prone to genomic instability.112 These patients progress to blast crisis much more rapidly than CML patients lacking the deletion and develop identical chromosomal abnormalities, consistent with the proposed explanation of a genetic mechanism (loss of a tumor suppressor/modifier gene?), which accelerates a BCR/ABL-driven disease process.112

The role of BCR/ABL in promoting genetic instability has been investigated in preleukemic transgenic mice expressing p190bcr/abl. Because these mice develop B-cell–type ALL at high frequency, it is unclear whether the findings may also apply to a preleukemic phase induced by p210bcr/abl. Nevertheless, in this mouse model of BCR/ABL-induced leukemia, point mutations, insertions, and deletions were detected with increased frequency in the preleukemic phase113,114 and their occurrence was, in part, blocked by treatment with imatinib mesylate.114

Microsatellite instability, a feature associated with tumor progression, does not seem to be involved in CML disease progression.115,116

Regardless of whether BCR/ABL has a direct or an indirect role in promoting genomic instability, 60% to 80% of patients with CML develop additional nonrandom chromosomal abnormalities involving chromosomes 8, 17, 19, and 22 with duplication of the Ph chromosome or trisomy 8 being the most frequent117 (Table 2).

At the molecular level, mutation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 is detected in approximately 25% to 30% of CML-myeloid blast crisis,118,119 whereas approximately 50% of the patients with lymphoid blast crisis present a homozygous deletion at the INK4A/ARF gene locus located on chromosome 9120 (Table 2). The most common chromosomal changes are trisomy of chromosome 8 (34%), trisomy of chromosome 19 (13%), double Ph chromosome (38%), isochromosome i(17q) (20%); these abnormalities can be also found in various combinations. Based on the frequency of the combinations in all metaphases and subclones, it has been suggested that i(17q) and trisomy of chromosome 8 are early changes, whereas trisomy 19 might occur late during disease progression.121 Some combinations, such as trisomy 8, double Ph chromosome, and i(17q), are more frequent than others; however, neither the presumed order of appearance nor the combination itself seems to have a clear impact on the prognosis of CML-BC.117 Moreover, the frequency of some secondary changes seems to depend on the therapeutic regimen.117

For example, chromosome 8 trisomy is more frequent in CML patients treated with busulfan (44%) than in those receiving hydroxyurea (12%). The frequency of the common CML secondary changes in patients treated with interferon α (IFN-α) and especially after bone marrow transplantation appears to be lower than in the group treated with busulfan,117 suggesting that the treatment with DNA-damaging agents (ie, busulfan) accentuates the genetic instability caused by the unrestrained tyrosine kinase activity of BCR/ABL. It will be interesting to see whether evolution into CML-BC of patients with CML treated with imatinib mesylate is also associated with a subset of the chromosomal abnormalities found in the “historical” group of CML patients predominantly treated with busulfan or hydroxyurea (or both).

Role of chromosomal abnormalities in CML disease progression

Whether and how the most common chromosomal abnormalities of CML-BC are pathogenetically linked to disease progression remains unclear and difficult to prove.

Chromosome 8 trisomy

Because the MYC gene is located at 8q24, it may be expected that chromosome 8 trisomy is associated with c-Myc overexpression and that this is pathogenetically involved in disease progression. Indeed, c-Myc is occasionally amplified and overexpressed in CML-BC,122 but there is no clear-cut correlation between trisomy of chromosome 8 and MYC amplification/overexpression.123 Furthermore, microarray analysis of AML with trisomy 8 as the sole chromosomal abnormality revealed a complex pattern of overexpression of several genes on chromosome 8 and on other chromosomes and down-regulation of others including c-Myc.124 Thus, the pathogenetic effects of chromosome 8 trisomy may not be limited to overexpression of a specific gene subset or a single gene. Nevertheless, expression of dominant-negative c-Myc molecules suppressed BCR/ABL-dependent transformation,125 and treatment of CML-BC cells with c-Myc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides suppressed in vitro colony formation and in vivo leukemogenesis,126 consistent with a role of c-Myc overexpression during disease progression.

Isochromosome i(17q)

A correlation between this genetic abnormality and a molecular mechanism of disease progression has not been established yet. The i(17q) abnormality leads to loss of 17p and has been thought to be associated with mutation of the remaining p53 allele. However, p53 mutations were not found in CML cases with the i(17q),127,128 raising the possibility that the relevant pathogenetic mechanism in CML-BC patients with the i(17q) abnormality is loss of function of yet unidentified genes. It is also possible that genetic inactivation of a p53 allele in combination with BCR/ABL-dependent effects (see “Role of molecular abnormalities in CML disease progression”)on the expression/activity of the remaining one remains the pathogenetically relevant mechanism in CML-BC with this chromosomal abnormality.

Double Ph chromosome

The role of the double Ph chromosome in disease progression is also unclear. Perhaps the presence of this chromosomal abnormality leads to increased expression of BCR/ABL, which has also been reported in advanced disease stages.18-20 However, the relationship between BCR/ABL levels and presence of the second Ph chromosome has not been formally tested. Whether the increased expression of BCR/ABL, per se, is sufficient to induce the phenotype of CML-BC cells is uncertain. For example, expression of BCR/ABL in retrovirus-transduced marrow cells is quite abundant99 and yet mice die because of a myeloproliferative disorder rather than an acute leukemia with accumulation of blast cells.

Perhaps, what matters is an increased and sustained expression of BCR/ABL in a primitive pool of hematopoietic progenitor cells, but a disease model dependent on BCR/ABL expression in these cells has not been established yet. Our group reported that expression of C/EBPα, a member of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family of transcription factors, which is required for myeloid differentiation,129 is down-regulated by BCR/ABL in a dose-dependant manner.130 Moreover, expression of C/EBPα restored granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–induced differentiation of BCR/ABL-expressing cells, suggesting that C/EBPα is a critical target in CML disease progression.130 Few genes up-regulated in CML-BC may be involved in the mechanisms whereby the double Ph chromosome promotes disease progression. One such gene is mdm2, which is activated by BCR/ABL after transcription131 and functions as a negative regulator of p53, thereby disabling the p53-mediated DNA damage response.

Expression of C/EBPα and mdm2 is, in part, regulated by p210BCR/ABL by activation of 2 RNA-binding proteins (hnRNP E2 and La) with a negative or positive effect on c/ebpα and mdm2 mRNA translation, respectively.

Two other genes up-regulated by BCR/ABL in CML-BC are Evi-1 and HOXA9, 2 transcription factors that can cooperate with BCR/ABL in blocking myeloid differentiation and enhancing the proliferative and survival advantage of BCR/ABL-expressing cells.132,133 Perhaps, the cumulative effect of mdm2, Evi-1, HOXA9, and other BCR/ABL targets involved in proliferation, survival, and differentiation coupled with down-regulation of C/EBPα leads incrementally to differentiation arrest, reduced apoptosis susceptibility, and enhanced proliferative potential of CML-BC cells.

That there are BCR/ABL dose-dependent mechanisms of altered gene regulation, clearly not limited to translational control of C/EBPα and mdm2 expression or Evi-1 and HOXA9 increased transcription, might be important to explain the disease process of CML-BC without chromosomal and molecular abnormalities and the relative sensitivity to imatinib mesylate of CML-BC cells. Twenty to 40% of patients with CML-BC do not exhibit chromosomal abnormalities and presumably only a fraction of these patients has molecular inactivation of the p53 gene, and yet their overall survival is only marginally better of those with chromosomal abnormalities.3,117 It is tempting to speculate that the disease burden of patients without chromosomal abnormalities is a consequence of the epigenetic changes (ie, down-modulation of C/EBPα, increased MDM2 levels) induced by BCR/ABL overexpression. The therapeutic response of CML-BC patients to imatinib mesylate may be, in part, also explained by suppression of the dosage-dependent effects of BCR/ABL, which are likely to coexist with the effects of chromosomal and molecular abnormalities. Inhibition of BCR/ABL activity is not expected to reverse the effects of the chromosomal and molecular abnormalities of CML-BC cells, whereas the consequences of BCR/ABL dose-dependent effects on gene expression would be reversed, at least until the emergence of cell subpopulations with mutant BCR/ABL, a process that may be also favored by BCR/ABL overexpression.134

Overexpression of BCR/ABL might be also involved in transcriptional repression by promoting hypermethylation of the regulatory regions of specific genes. One such gene is c-Abl itself, which is hypermethylated and expressed at low levels in CML-BC.135 The c-Abl protein has been implicated in the DNA damage response and in apoptosis136 ; thus, down-modulation of c-Abl expression might further reduce susceptibility to DNA damage-induced apoptosis of BCR/ABL-expressing cells while enhancing their genomic instability, 2 features that can contribute to disease progression. The involvement of c-Abl loss in disease progression remains speculative because it has not been tested yet in any in vitro or in vivo model of BCR/ABL-dependent transformation of hematopoietic cells.

The (3;21)(q26;q22) and (7;11)(p15;p15) translocations

The pathogenic effects of secondary genetic alterations in CML-BC are more clear in t(3;21)(q26;q22) associated with expression of the AML-1/EVI-1 fusion protein137 and t(7;11)(p15;p15) associated with expression of the NUP98/HOXA9 fusion protein.138 The t(3;21)(q26;q22) translocation has been found in approximately 2% of myeloid CML-BC; the t(7;11)(p15;p15) translocation is even less frequent. Coexpression of BCR/ABL and AML-1/EVI-1 in mouse marrow cells induces a disease process characterized by accumulation of differentiation-arrested blast cells.139 This is consistent with the observation that AML-1/EVI-1 suppresses AML-1–dependent transactivation of differentiation-regulatory genes and inhibits G-CSF–induced differentiation of myeloid precursor 32Dcl3 cells.132 Moreover, the chimeric AML-1/EVI-1 protein (and the non-rearranged EVI-1) appears to interact with SMAD3, a nuclear effector of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), thereby suppressing the growth inhibitory effects of TGF-β.140,141

The t(7;11)(p15;p15) translocation is an infrequent secondary abnormality in CML-BC, but the chimeric NUP98/HOXA9 protein appears to be relevant in disease progression. Mice inoculated with marrow cells expressing the NUP98/HOXA9 chimera developed a myeloproliferative disorder that progressed to AML after a latency of 4 to 9 months.142 Coexpression of BCR/ABL and NUP98/HOXA9 caused a much more rapid disease process reminiscent of myeloid CML-BC.143,144 Of note, expression of HOXA9 was more abundant in 3 blast crisis samples compared to the corresponding chronic phase mononuclear fraction,144 suggesting that enhanced HOXA9 expression may be involved in disease progression also in CML-BC patients without the t(7;11)(p15;p15) translocation. Another interesting aspect of these studies relates to the mechanisms whereby NUP98/HOXA9 cooperates with BCR/ABL. NUP98/HOXA9 functions as a potent transcription factor133 and induces a myeloproliferative disorder that appears to depend on increased proliferation and survival of myeloid progenitors.142 The in vivo effects of NUP98/HOXA9 are reminiscent of those of BCR/ABL but are markedly slower, thus allowing us to distinguish a preleukemic and a frank leukemic stage.142

As elegantly proposed by Gilliland and Tallman,145 AML appears to require at least 2 genetic events, one of which, exemplified by activating mutations of the FLT3 receptor, endows cells with a proliferative and survival advantage, whereas the other, exemplified by formation of the PML-RARα chimera of the APL, provides a molecular mechanism for differentiation arrest. Although this model is conceptually useful because it points to the existence of genetic mechanisms responsible for dysregulation of differentiation, often the differentiation arrest of leukemic cells (including CML-BC) is better explained by epigenetic mechanisms (ie, suppression of C/EBPα activity). In mouse models of CML-BC, the disease process induced by coexpression of BCR/ABL and AML-1/EVI-1 fits nicely with the requirement of 2 complementary mutations (one promoting proliferation, the other blocking differentiation), but that induced by BCR/ABL and NUP98/HOXA9 does not seem to depend, at least directly, on 2 clearly distinguishable functions. Arguably, the differentiation arrest of CML-BC cells expressing BCR/ABL and NUP98/HOXA9 is not due to a direct effect of NUP98/HOXA9 on differentiation regulatory pathways because increased proliferation and survival characterizes NUP98/HOXA9-expressing cells.142 The cumulative activity of BCR/ABL and NUP98/HOXA9 is likely to cause the expansion of a stemprogenitor cell population no longer sensitive to differentiation-inducing stimuli.

Role of molecular abnormalities in CML disease progression

The most common gene mutations in CML-BC involve the p53 gene (which is mutated in 25%-30% of myeloid CML-BCs) and the INK4A/ARF exon 2 (which is homozygously deleted in approximately 50% of lymphoid CML-BCs).

The pathogenic role of p53 loss of function in CML disease progression has been tested using 2 different strategies. We showed that mice injected with p53-deficient, BCR/ABL-expressing marrow cells developed a more aggressive disease process than those injected with wild-type p53, BCR/ABL-expressing marrow cells.146 Compared to p53 wild-type cells, p53-deficient BCR/ABL-expressing marrow cells were homogeneously morphologically undifferentiated, more resistant to apoptosis induced by growth factor deprivation, and maintained high clonogenic potential in growth factor-deprived cultures.146

Blastic transformation of marrow cells was also obtained in a transgenic model in which mice expressing p210BCR/ABL under the control of the Tec promoter were crossed with p53-heterozygous (p53+/-) mice.147

The BCR/ABL+/-, p53+/- mice died of acute leukemia, which was preceded by a myeloproliferative disorder resembling human CML. Interestingly, the residual normal p53 allele of BCR/ABL-expressing blast cells was frequently lost, implying the existence of a BCR/ABL-dependent mechanism facilitating loss of the remaining p53 allele. In this transgenic model, all leukemias were clonal T-cell tumors, which is reminiscent of the spontaneously occurring T-cell lymphoma of p53-/- mice.148 One interpretation of these findings is that BCR/ABL accelerates the tumorigenic conversion of cells prone to transformation by inactivation of one p53 allele.

Despite the absence of an ideal in vivo model testing the role of p53 loss of function in myeloid blast crisis, p53 loss can contribute to disease progression in several ways.

Compared to wild-type marrows, p53-/- cells showed a 3- to 4-fold increase in the frequency of multipotent progenitors (Lin-Sca-1+, CD34+) and a greater number of hematopoietic stem cells capable of hematopoietic reconstitution in lethally irradiated mice.149 Moreover, these cells were less susceptible to apoptotic stimuli.149 Lineage commitment and differentiation of p53-/- progenitors were not affected, suggesting that loss of p53, per se, does not cause differentiation arrest.149 Thus, the differentiation arrest of CML-BC cells lacking a functional p53 gene may be due to the effect of BCR/ABL in an expanded pool of hematopoietic progenitors or secondary mutations induced by the cumulative effects of BCR/ABL and p53 loss of function in promoting genomic instability.

A common mutation in CML-BC is homozygous deletion of exon 2 at the INK4A/ARF locus. The frequency of this mutation is approximately 50% in lymphoid blast crisis but is undetectable in myeloid blast crisis.120,150,151 Exon 2 deletion of the INK4A/ARF locus is expected to result in loss of expression of p16 and p14/ARF, 2 proteins that regulate cell cycle progression and the G1/S checkpoint by inhibiting the G1 phase cyclin D-Cdk4/Cdk6 and promoting p53 up-regulation, respectively. Based on tumor susceptibility of p16INK4A or ARF knockout mice, loss of p19/ARF appears to be more important than loss of p16 for tumor formation including lymphomas and lymphoid leukemias. Mice with targeted disruption of both the p16INK4A/p19ARF loci (p16INK4A-/-/p19ARF-/-) developed lymphomas and lymphoid leukemias with low penetrance.152 Homozygous disruption of only the p19ARF alleles (p16INK4A+/+/p19ARF-/-) also resulted in development of lymphomas, and tumors that developed in the heterozygous p19 ARF+/- mice lost the remaining wild-type allele,153,154 suggesting a selective advantage for (pre)malignant lymphoid cells losing both ARF alleles.153,154 Mice with a disruption of both alleles of p16INK4A and an intact p19ARF (p16INK4A-/-/p19ARF+/+) have only a moderately increased cancer susceptibility.155,156 The availability of these models of p16/ARF loss of function should allow one to determine the involvement of each gene in BCR/ABL leukemogenesis because previous evidence of a dominant role of p19 genetic inactivation in v-Abl lymphomagenesis is indirect.157 The involvement of p16 and ARF in the maintenance of adult self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells has recently been suggested by a study in which ectopic expression of p16 or ARF in hematopoietic stem cells (c-Kit+, Sca-1+, Flt3-Lin-) suppressed their proliferation, with ARF being more potent than p16.158 Thus, it is likely that loss of p16 and ARF-dependent p53 activity are both necessary for lymphoid transformation in the subset of CML-BC patients with homozygous deletion of the p16/ARF locus. However, the relative contribution of p16 and ARF is unknown. Based on the relationship between ARF and p53 expression, where ARF induces increased p53 levels by interfering with its MDM2-dependent degradation,159 homozygous deletion at the p16/ARF locus observed in lymphoid blast crisis might represent a functional equivalent of p53 mutation in myeloid blast crisis. However, ARF appears to have also p53-independent effects,160 which could contribute to the phenotype of lymphoid blast crisis cells.

Loss of p16INK4A leads indirectly to abrogation/attenuation of the cell cycle regulatory effects of the p105 retinoblastoma protein (RB); however, the Rb gene itself is inactivated by mutation, deletion, or loss of expression in approximately 18% of accelerated or blast crisis CML cases, especially those associated with a megakaryoblastic or lymphoblastic phenotype.161-163

A unifying mechanism for disease progression in CML

As discussed, CML-BC is characterized by several seemingly incoherent chromosomal and molecular abnormalities. Yet, some generalizations can be attempted: (1) the vast majority of secondary changes involve genes encoding nucleus-localized proteins that directly or indirectly regulate gene transcription; (2) mutations/loss of function of tumor suppressor genes is predominant over mutation/activation of oncogenes; and (3) p53 is genetically or functionally inactivated in a large fraction of CML-BC cases.

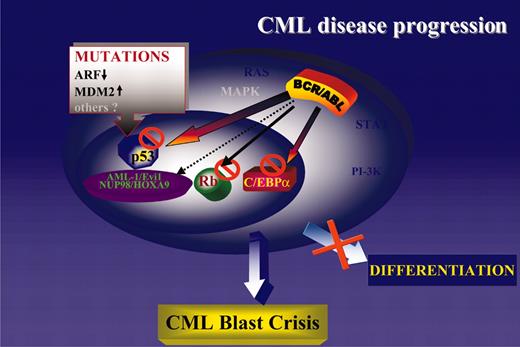

Consistent with the central role of the cytoplasm-localized BCR/ABL in disease initiation and progression, it is not surprising that most secondary changes of CML-BC involve genes encoding nucleus-localized proteins. The BCR/ABL oncoprotein activates several signal transduction pathways regulating cell proliferation and survival, and additional mutations activating these pathways would be of no obvious advantage. Indeed, mutation of K-RAS or N-RAS is a rare event in CML-BC,164,165 and mutation of PTEN, which is frequent in solid tumors and leads to constitutive activation of the PI-3K/Akt pathway, has not been detected in any leukemia sample including CML.166 Thus, mutations of nucleus-localized gene products might complement the effects of the cytoplasm-localized BCR/ABL by (1) activating or repressing transcription directly (NOP98/HOXA9 and AML-1/EVI-1, respectively); (2) generating a nonfunctional transcription factor (ie, p53 mutant); and (3) indirectly modulating the activity of transcription factors involved in DNA synthesis (ie, homozygous deletions of the p16INK4A/ARF locus leading to inactivation of the Rb pathway and enhanced activity of E2F family genes) or in cell cycle checkpoints (ie, homozygous deletions of the p16INK4A/ARF locus leading to MDM2-dependent inactivation/degradation of p53). Regardless of the predominant secondary changes of CML-BC, in any of the above situations the phenotype is remarkably similar and consists of growth factor-independent proliferation and survival coexisting with a severe differentiation arrest. The latter distinguishes blast crisis from chronic-phase CML, but proliferation of CML-BC cells is often exuberant and independent of growth factors.131,167 The most likely interpretation of these findings is that the differentiation arrest of CML-BC cells can be enforced by mutations/down-regulation of differentiation-regulatory genes (ie, generation of the AML-1/EVI-1 chimera or reduced C/EBPα expression), as well as by activation of proliferation-stimulatory pathways (ie, homozygous deletion of the p16INK4A/ARF locus with secondary effects on the RB and p53 pathway; Figure 4).

A unifying model of CML disease progression. Genetic or functional inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (p53 and Rb) is the most common abnormality in CML-BC. Loss of C/EBPα expression is also common and promotes differentiation arrest and proliferative advantage due to inhibition of cell proliferation by wild-type C/EBPα.170

A unifying model of CML disease progression. Genetic or functional inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (p53 and Rb) is the most common abnormality in CML-BC. Loss of C/EBPα expression is also common and promotes differentiation arrest and proliferative advantage due to inhibition of cell proliferation by wild-type C/EBPα.170

In many cell types, differentiation is preceded by reduced proliferation and an abnormally high proliferative rate in a specific stem/progenitor cell subset might lead to expansion of a cell population unfit to differentiate. Most secondary genetic abnormalities in CML-BC directly inactivate genes that function as tumor suppressors (ie, p53 gene mutations) or lead to functional inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (ie, homozygous deletion of ARF leading to p53 loss of function; Figure 4). In this regard, CML disease progression is similar to the transition from a premalignant to a frank neoplastic state in solid tumors, but, in contrast to CML and other hematologic malignancies, in solid tumors the initiating event is often represented by inactivation of a tumor suppressor gene.

Genetic or functional inactivation of p53 seems the most common abnormality in CML-BC because the p53 gene is mutated in 25% to 30% of myeloid CML-BCs; homozygous deletion of the p16INK4A/ARF locus, which indirectly affects p53 function, is detected in approximately 50% of CML lymphoid blast crisis, and expression of MDM2, the principal negative regulator of p53, is often more abundant in CML-BC mononuclear cells, compared to the corresponding chronic-phase cells.131 Other mechanisms potentially leading to functional inactivation of p53 (ie, cytoplasmic sequestration) have not been examined, making difficult a quantitation of the actual involvement of p53 in CML disease progression.

Conclusions and future directions

A legitimate model of disease progression in CML predicts that BCR/ABL activity promotes the accumulation of molecular and chromosomal alterations directly or indirectly responsible for the reduced apoptosis susceptibility and the enhanced proliferative potential and differentiation arrest of CML-BC cells. Although good animal models are not yet available, evidence suggests a mechanism of CML disease progression where alterations in DNA repair processes coupled with enhanced survival of BCR/ABL-expressing cells may allow the propagation of secondary genetic changes that favor the emergence and persistence of increasingly malignant cells. Among the secondary changes, those directly or indirectly affecting the p53 tumor suppressor gene seem to have a central role for frequency and biologic consequences.

At the molecular level, CML-BC remains a heterogeneous disease and yet only few pathways are commonly affected. Of the many issues that need to be investigated for a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms in CML disease progression, some should attract considerable attention.

First, is BCR/ABL overexpression a common feature of CML-BC and is it determined stochastically or by genetic/epigenetic mechanisms?

Recent evidence suggests that expression of BCR/ABL is more abundant in early than in late CML chronic-phase progenitors168 and that CML-BC undifferentiated and committed myeloid progenitors express higher BCR/ABL levels of the corresponding chronicphase progenitors.20 If this is confirmed by additional studies, an obvious question will be whether BCR/ABL overexpression is causally linked or secondary to the expansion of homogeneous populations of blast cells. A molecular characterization of apparently identical subpopulations of CML chronic phase and blast crisis progenitors and their comparison with normal progenitors may prove important in addressing these possibilities. Overexpression of BCR/ABL during disease progression may be the result of stochastic forces or facilitated by genetic/epigenetic mechanisms. Comparison of BCR/ABL levels in CML-BC patients without and with chromosomal/molecular abnormalities could be informative in supporting or disproving either possibility.

Second, are there specific molecular determinants of lymphoid CML-BC and do they interact with BCR/ABL in selectively promoting the expansion of B cell-type blasts?

The high frequency of homozygous deletions at the INK4A/ARF locus suggests that inactivation of the INK4A or ARF gene or both serves as the important molecular determinant of lymphoid blast crisis. Because specific knockout models (INK4A-/-, ARF-/-, and INK4A/ARF-/-) are available, it will be important to test whether INK4A, ARF, or the combination of both mutants cooperates with BCR/ABL to induce the selective expansion of a pool of B cell-type unipotent progenitors. Perhaps, loss of the INK4A or ARF gene or both favors cell cycle entry of B cell-type rather than myeloid progenitors. Loss of p16 and ARF function is required for immortalization of human cells, whereas loss of ARF is sufficient for immortalization and RAS-dependent transformation of mouse cells169 ; thus, the role of ARF and p16 should be also independently tested in in vitro models of BCR/ABL transformation of multipotent and unipotent human progenitor cells.

Third, will disease progression and development of secondary genetic abnormalities be affected by treatment with imatinib mesylate?

If disease progression depends on the constitutive activity of the BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase, suppressing its activity will postpone, if not prevent, the development of CML-BC. Although there is no proof for it, the secondary changes of CML-BC may reflect, in part, the effects of treatment with DNA-damaging agents on the genetically unstable background of BCR/ABL-expressing cells. If so, CML-BC resistant to imatinib mesylate might be characterized by a distinct pattern of secondary changes primarily caused by the constitutive activity of BCR/ABL.

The ultimate goal of BCR/ABL kinase inhibitor-based CML therapy is disease eradication and prevention of transition to blast crisis. Because it is unlikely that this will be achieved in each patient, understanding disease progression in the group resistant to imatinib mesylate will be essential for the development of “rational” therapeutic strategies to be used in conjunction with BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Note added in proof. After this review was accepted for publication, a paper was published171 that investigated the relationship of BCR/ABL expression and DNA double-strand damage after etoposide treatment.

This study by Dierov et al171 reports that BCR/ABL interacts with ATR in the nucleus and suppresses its activity, implicating this mechanism in the increased DNA double-strand breaks after etoposide treatment. It is unclear whether suppression of ATR activity by BCR/ABL contributes to the accumulation of genetic abnormalities in CML-BC, but the study by Dierov et al171 points to the complexity of the relationship between BCR/ABL and DNA repair.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 24, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4111.

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA16058; National Institutes of Health grants RO1 CA095512 (D.P.) and PO1 CA78890 (B.C.); and a Department of the Army CMLRP (DAMD17-03-1-0184) grant (D.P.). The support of the Elsa U. Pardee and the Lauri Strauss Leukemia Foundation is also gratefully acknowledged.

We thank Bice Perussia and Carlo Gambacorti-Passerini for critical reading of the manuscript and Catherine Tomastik for editorial assistance.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal