Abstract

Continuous xenografts from 10 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) were established in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice. Relative to primary engrafted cells, negligible changes in growth rates and immunophenotype were observed at second and third passage. Analysis of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangements in 2 xenografts from patients at diagnosis showed that the pattern of clonal variation observed following tertiary transplantation in mice exactly reflected that in bone marrow samples at the time of clinical relapse. Patients experienced diverse treatment outcomes, including 5 who died of disease (median, 13 months; range, 11-76 months, from date of diagnosis), and 5 who remain alive (median, 103 months; range, 56-131 months, following diagnosis). When stratified according to patient outcome, the in vivo sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine and dexamethasone, but not methotrexate, differed significantly (P = .028, P = .029, and P = .56, respectively). The in vitro sensitivity of xenografts to dexamethasone, but not vincristine, correlated significantly with in vivo responses and patient outcome. This study shows, for the first time, that the biologic and genetic characteristics, and patterns of chemosensitivity, of childhood ALL xenografts accurately reflect the clinical disease. As such, they provide powerful experimental models to prioritize new therapeutic strategies for future clinical trials.

Introduction

Over the past 40 years refinements in the multiagent chemotherapy regimens and supportive care for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have led to dramatic improvements in outcome.1 Nevertheless, the treatment options for those patients who suffer early bone marrow relapse are limited,2 and ALL remains one of the most common causes of death from disease in children.1 Furthermore, as increasing numbers of children survive into adulthood the delayed consequences of their therapy are becoming apparent.3,4

Due to the limitations imposed by the number of children eligible for clinical trials relative to the availability of new agents, additional improvements in the therapy of childhood ALL may depend on the use of relevant preclinical experimental models to prioritize novel therapies for future clinical trials. The development of models of childhood ALL that mimic the clinical manifestations of the disease has proven problematic. Historically, the engraftment efficiency of normal and malignant human hematopoietic cells in strains of immune-deficient mice, such as severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, has been low.5,6 Consequently, a renewable source of childhood ALL cells that retain the essential characteristics of the original disease has remained elusive.

More recently, the nonobese diabetic (NOD)/SCID mouse strain was shown to be receptive to engraftment of normal and malignant human hematopoietic cells.7-15 Moreover, several groups have now reported the efficient engraftment of childhood ALL primary biopsy specimens, albeit from predominantly high-risk or poor-outcome patients11,12,15 or exclusively T-lineage ALL.13,14 However, no studies to date have attempted to correlate the chemosensitivity of a series ofALL xenografts with the patients'clinical outcome.

We previously described the engraftment in NOD/SCID mice of 20 childhood ALL biopsies obtained at diagnosis or relapse from patients who encompassed a broad range of disease subtypes and treatment outcomes.16 The relevance of these xenograft models to the clinical disease was highlighted by the preservation of leukemic blast morphology in the murine peripheral blood, sites of organ infiltration, immunophenotype, and the absence of mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene.

The present study reports the development and characterization of 10 continuous xenografts from children who experienced diverse treatment outcomes. The relative sensitivity of these xenografts to drugs used to treat childhood ALL was monitored in real time by sampling murine peripheral blood. The range of xenograft drug responses, and their correlation with patient clinical outcome, indicate that they will provide a valuable resource for the preclinical evaluation of new therapies.

Materials and methods

NOD/SCID mouse model of childhood ALL

All experimental studies were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee and the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the University of New South Wales. Procedures by which we previously engrafted 20 childhood ALL biopsies into NOD/SCID mice have been described in detail.16 Following inoculation with human leukemia cells via the tail vein, mice were monitored every 7 days for engraftment by staining approximately 50 μL peripheral blood taken from the tail vein with anti-CD45 (leukocyte common antigen, Ly-5) antibodies; fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antimurine and allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated antihuman CD45 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) as previously described.16 The rate of engraftment was previously established as the number of days following transplantation for leukemia cells to disseminate and reach a proportion of 1% human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood.16

Continuous xenografts were established by harvesting human leukemia cells from the spleens of engrafted mice, exactly as described previously.16 Preparations of childhood ALL cells used to establish continuous childhood ALL xenografts from mouse spleens routinely consisted of more than 3 × 108 cells per spleen at more than 85% purity.16

Prior to inoculation into secondary or tertiary recipient mice, cells were thawed rapidly in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and processed as previously described.16 For a comparison of rates of secondary and tertiary engraftment with the rate of primary engraftment, equal numbers of human leukemia cells were inoculated into groups of 4 mice in each case.

Expression of a range of lineage-specific and differentiation markers on the surface of cells harvested from the spleens of engrafted mice was analyzed using standard procedures as previously described.16

Identification of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangements

Clonal rearrangements of the immunoglobulin (Ig) or T-cell–receptor (TCR) genes were determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. A total of 25 antigen receptor gene rearrangements including 7 IGH, 5 IGK-Kde (kappa deletion element), 7 TCRG, and 6 TCRD were analyzed using primers and conditions as previously described.17 Clonality of any PCR product identified was determined using heteroduplex analysis.18 Monoclonal products were directly sequenced while oligoclonal products were further amplified by PCR using internal primers. Sequences were compared against germ line sequences to identify and characterize the V-N-(D)-N-J region.

In vivo drug treatments

Our previous report assessed the in vivo responses of 6 xenografts to vincristine.16 The present study describes a more detailed analysis of the responses of a larger panel of xenografts to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. Groups of 4 mice were inoculated with 3 × 106 to 5 × 106 mononuclear cells purified from the spleens of secondary recipient mice, and engraftment was monitored by flow cytometry as described above. When the proportion of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood reached 1%, mice were randomized to receive drug or saline control treatment. All drug administration was intraperitoneal, and consisted of vincristine (0.5 mg/kg every 7 days for 4 weeks), dexamethasone (15 mg/kg Monday-Friday for 4 weeks), or methotrexate (5 mg/kg Monday-Friday every 14 days for 8 weeks). The proportion of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood was monitored throughout and following the course of treatment, and the event-free survival (EFS) was calculated from the initiation of treatment exactly as described previously.16 Mouse EFS was graphically represented by Kaplan-Meier analysis.19 For statistical comparisons between xenografts and drug treatments, the median EFS for control mice was subtracted from the median EFS for drug-treated mice to generate a growth delay factor (GDF).

In vitro cell culture and drug sensitivity assays

In preliminary experiments carried out to determine optimum culture conditions for in vitro chemosensitivity assays, xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage and cultured (1) on a monolayer of human bone marrow fibroblasts in AIM V medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA)20-22 ; (2) on a monolayer of the murine bone marrow stromal (MS-5) cell line in QBSF-60 medium (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) containing 20 ng/mL Flt-3 ligand (QBSF-60/F; Immunex, Seattle, WA)23,24 ; or (3) in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) containing 15% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and l-glutamine (2 mM).25

To assess in vitro drug sensitivity, 1 × 104 MS-5 cells in α–minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Invitrogen Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and l-glutamine (2 mM), were seeded per well of a 96-well tissue-culture plate and allowed to grow to confluence. Xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage, resuspended in QBSF-60/F medium at 2 × 106 cells/mL and 100 μL added to each well. Following overnight incubation, chemotherapeutic drugs were added, as indicated, and the plates were incubated for an additional 3 days. Cells were then harvested, and human CD45+ cells appearing in the viable region by forward- and side-scatter characteristics were enumerated exactly as described in detail elsewhere.20,21 Cell survival at each drug concentration was expressed relative to solvent-treated controls. Experiments were excluded from the analysis if the control cell count on day 4 was less than 50% of day-1 values. Data presented are the mean plus or minus standard error of the mean (SEM) of at least 3 separate experiments, each with duplicate wells per data point. Prior experiments had verified that the drugs used were nontoxic toward MS-5 cells alone.

High-resolution cell division tracking

The methodology adopted for monitoring the proliferation of xenograft cells in short-term culture using the fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), was essentially as described by Nordon et al for hematopoietic cells.26 Freshly thawed xenograft cells in QBSF-60/F medium were incubated with 0.75 μM CFSE for 10 minutes at 37° C in the dark. Cells were resuspended in CFSE-free medium, incubated overnight, and sorted using a FACS-VantageSE with DiVa option (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Sorting gates were set around the central histogram peak at a width of 34 to 40 channels of a total of 1024 on a linear scale, to obtain the most homogenously staining cell populations. Sorted cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in QBSF-60/F medium at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL, and plated on a monolayer of MS-5 cells, as described in the previous section. At daily intervals thereafter cells were harvested by vigorous pipetting and analyzed using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Cells that had divided were identified by halving of fluorescence intensity (relative to colcemid-treated undivided cells) at each generation. Independent experiments verified that 100% of divided cells were human CD45+ and not contaminated with murine cells (data not shown). The proliferation index at each time point was calculated using ModFit LT version 2.0 Proliferation Wizard software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME), as described in detail elsewhere.26

Statistical comparisons

Correlations between quantitative variables were determined by regression analysis using StatView software version 5.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each analysis a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated, and a Fisher r-to-z transformation was carried out to calculate a probability level (P value) for the null hypothesis that the correlation is equal to zero. Quantitative variables were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. For all statistical tests, the level of significance was set to .05.

Results

Establishment of continuous xenografts in NOD/SCID mice

We previously reported the engraftment in NOD/SCID mice of 20 primary childhood ALL samples (14 at initial diagnosis and 6 at relapse) from diverse disease subtypes and treatment outcomes.16 The rate of engraftment of these samples ranged from 19 to 190 days.16 In order to develop xenograft models for in vivo chemosensitivity testing, continuous xenografts were established from the 10 leukemias that exhibited the most rapid rates of engraftment (range, 19-64 days),16 by transplanting cells harvested from the spleens of engrafted animals to secondary and tertiary recipient mice. The relevant disease-specific details of the patients with leukemia are shown in Table 1. Notably, 5 xenografts were derived from patients who relapsed in their bone marrow and subsequently died from their disease, while the other 5 patients remain alive more than 4.5 years (range, 56-131 months) from diagnosis (3 in first complete remission [CR1], 2 in second complete remission [CR2]).

Patient clinical data

Xenograft . | Age at diagnosis, in months/sex . | ALL subtype . | Disease status at biopsy . | Length of CR1, in months . | Site of relapse . | Survival after first relapse, in months . | Current clinical status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL-2 | 65/F | c-ALL | Relapse 3 | 30 | BM/CNS | 46 | DOD |

| ALL-3 | 154/F | Pre-B | Diagnosis | 38 | BM | 93* | CR2 |

| ALL-4 | 105/M | Ph+, c-ALL | Diagnosis | 10 | BM | 1 | DOD |

| ALL-7 | 88/M | Biphen | Diagnosis | 7 | BM | 6 | DOD |

| ALL-8 | 152/M | T-ALL | Relapse 1 | 17 | BM | 1 | DOD |

| ALL-10 | 48/M | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 57* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-11 | 37/F | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 120* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-16 | 122/F | T-ALL | Diagnosis | 103* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-17 | 107/F | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 25 | CNS | 31* | CR2 |

| ALL-19 | 194/M | c-ALL | Relapse 1 | 4 | BM | 7 | DOD |

Xenograft . | Age at diagnosis, in months/sex . | ALL subtype . | Disease status at biopsy . | Length of CR1, in months . | Site of relapse . | Survival after first relapse, in months . | Current clinical status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL-2 | 65/F | c-ALL | Relapse 3 | 30 | BM/CNS | 46 | DOD |

| ALL-3 | 154/F | Pre-B | Diagnosis | 38 | BM | 93* | CR2 |

| ALL-4 | 105/M | Ph+, c-ALL | Diagnosis | 10 | BM | 1 | DOD |

| ALL-7 | 88/M | Biphen | Diagnosis | 7 | BM | 6 | DOD |

| ALL-8 | 152/M | T-ALL | Relapse 1 | 17 | BM | 1 | DOD |

| ALL-10 | 48/M | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 57* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-11 | 37/F | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 120* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-16 | 122/F | T-ALL | Diagnosis | 103* | — | — | CR1 |

| ALL-17 | 107/F | c-ALL | Diagnosis | 25 | CNS | 31* | CR2 |

| ALL-19 | 194/M | c-ALL | Relapse 1 | 4 | BM | 7 | DOD |

Biphen indicates biphenotypic; BM, bone marrow; c-ALL, common (CD10+) ALL; CNS, central nervous system; CR1, alive in first complete remission; CR2 alive in second complete remission; DOD, dead of disease; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome—positive ALL; and —, no relapse.

No event (censored).

When equivalent numbers of cells were inoculated, the rate of engraftment did not differ significantly between primary, secondary, and tertiary passage for 6 xenografts, whereas 3 xenografts accelerated at second and third passage (ALL-2, -4, and -17), and another only at third passage (ALL-16) (Table 2).

Rates of primary, secondary, and tertiary engraftment

. | Time to engraftment, day ± SD . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | Primary . | Secondary . | Tertiary . | ||

| ALL-2 | 53 ± 5 | 44 ± 6* | 32 ± 3* | ||

| ALL-3 | 25 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 | 30 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-4 | 57 ± 5 | 31 ± 3* | 30 ± 2* | ||

| ALL-7 | 19 ± 5 | 20 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | ||

| ALL-8 | 47 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 | 41 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-10 | 31 ± 10 | 37 ± 11 | 31 ± 1 | ||

| ALL-11 | 45 ± 8 | 46 ± 3 | 45 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-16 | 55 ± 11 | 47 ± 3 | 39 ± 5* | ||

| ALL-17 | 64 ± 7 | 33 ± 4* | 38 ± 2* | ||

| ALL-19 | 29 ± 11 | 25 ± 6 | 27 ± 4 | ||

. | Time to engraftment, day ± SD . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | Primary . | Secondary . | Tertiary . | ||

| ALL-2 | 53 ± 5 | 44 ± 6* | 32 ± 3* | ||

| ALL-3 | 25 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 | 30 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-4 | 57 ± 5 | 31 ± 3* | 30 ± 2* | ||

| ALL-7 | 19 ± 5 | 20 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | ||

| ALL-8 | 47 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 | 41 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-10 | 31 ± 10 | 37 ± 11 | 31 ± 1 | ||

| ALL-11 | 45 ± 8 | 46 ± 3 | 45 ± 4 | ||

| ALL-16 | 55 ± 11 | 47 ± 3 | 39 ± 5* | ||

| ALL-17 | 64 ± 7 | 33 ± 4* | 38 ± 2* | ||

| ALL-19 | 29 ± 11 | 25 ± 6 | 27 ± 4 | ||

Significantly different from rate of primary engraftment (P < .05).

Our previous analysis of the immunophenotype of 13 leukemias before and after primary engraftment in NOD/SCID mice revealed that expression of a single cell surface antigen changed in only 4 xenografts.16 The analyses represented in Table 3 indicate that the previously reported increase in the proportion of CD34+ cells in xenografts ALL-2 and ALL-11 (albeit moderate in ALL-11) at first passage was maintained during secondary and tertiary engraftments, as was the decrease in CD13 expression by ALL-7. In addition, staining for the common ALL antigen, CD10, in ALL-16 was low at biopsy (26% of cells) and at first and second passage (42% and 30% of cells, respectively), but had diminished at third passage (< 1% of cells). ALL-19 acquired a minor proportion of cells (49%) staining positive for CD33 at second passage, which was not apparent at biopsy, primary, or tertiary passage.

Immunophenotype of original patient biopsy sample compared with spleen-derived cells following primary, secondary, and tertiary engraftment

Xenograft . | Origin of sample . | Immunophenotype (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| ALL-2 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34- (2) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (86) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (89) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (92) | |

| ALL-3 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10- |

| ALL-4 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+ |

| ALL-7 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34-/11b+/ 33+/13+ (52) |

| NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34-/11b+/ 33+/13- (< 1) | |

| ALL-8 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3+/2+/7+/8+/ 34-/13+ |

| ALL-10 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ |

| ALL-11 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34- (< 1) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (40) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (40) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (33) | |

| ALL-16 | Biopsy | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10- (26) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10+ (42) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10+ (30) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10- (< 1) | |

| ALL-17 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+/33- |

| ALL-19 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33+ (49) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) |

Xenograft . | Origin of sample . | Immunophenotype (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| ALL-2 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34- (2) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (86) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (89) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ (92) | |

| ALL-3 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10- |

| ALL-4 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+ |

| ALL-7 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34-/11b+/ 33+/13+ (52) |

| NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34-/11b+/ 33+/13- (< 1) | |

| ALL-8 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3+/2+/7+/8+/ 34-/13+ |

| ALL-10 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+ |

| ALL-11 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34- (< 1) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (40) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (40) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/33-/34+ (33) | |

| ALL-16 | Biopsy | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10- (26) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10+ (42) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10+ (30) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR-/CD19-/3-/7+/8+/33-/ 13-/10- (< 1) | |

| ALL-17 | Biopsy; NOD/SCID 1°, 2°, 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/10+/34+/33- |

| ALL-19 | Biopsy | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) |

| NOD/SCID 1° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) | |

| NOD/SCID 2° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33+ (49) | |

| NOD/SCID 3° | HLA-DR+/CD19+/3-/22+/10+/34+/ 33- (< 1) |

Boldface denotes differences in expression between biopsy and NOD/SCID engrafted cells, with the proportion of positive cells in parentheses. The cut-off for positivity was set at 30% of cells staining more intensely than the isotype control antibody, consistent with standard hematologic procedures (see “Materials and methods” for details). In the interest of space, complete data are shown only for those xenografts that exhibited any differences in immunophenotype following engraftment.

1° indicates primary engraftment; 2°, secondary engraftment; 3°, tertiary engraftment.

With the exception of the minor differences noted above, the immunophenotype of childhood ALL cells has remained stable for at least 3 passages in NOD/SCID mice. Due to the overall stability of engraftment rates and immunophenotype, all subsequent experiments to assess chemosensitivity used xenograft cells undergoing third passage at the time of drug treatment.

Analysis of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangements

To compare the genotypic characteristics of ALL cells passaged in NOD/SCID mice with their matched counterparts obtained from patients, we determined the clonal pattern of antigen receptor gene rearrangements present in a range of samples. Such rearrangements are unique due to random insertions and/or deletions of nucleotides at the junctional regions of Ig or TCR genes and can thus serve as clonal markers of disease in individual patients. However, despite their utility, rearrangements may also undergo clonal evolution (ie, be lost or altered) in up to a third of patients during the course of their disease. Such clonal evolution may be due to an ongoing rearrangement process or to the selection of a population subclone that was undetectable at time of diagnosis.

ALL-7 and ALL-17 xenografts were examined for clonal rearrangements of antigen receptor genes. Both these xenografts were derived from diagnosis ALL samples of patients who subsequently relapsed. From a total of 25 rearrangements investigated (see “Materials and methods”), 6 clonal sequences were identified for ALL-17 (2 TCRG, 2 IGH, and 2 IGK-Kde) following tertiary engraftment. Identical clonal rearrangements were present in both the patient diagnosis sample from which these leukemic cells were obtained, as well as the subsequent bone marrow sample taken at relapse (data not shown). Thus, the stability of the clonal rearrangements observed in this particular leukemia between diagnosis and clinical relapse was also observed following 3 serial passages in NOD/SCID mice.

The results for ALL-7 are shown in Table 4. For the leukemia sample obtained at diagnosis of the patient, 5 clonal rearrangements were detected, and 3 of these (IGH, and 2 IGK-Kde sequences) were preserved both at the time of clinical relapse and also in the tertiary transplant sample. Interestingly, however, an IGK-intron-Kde rearrangement present at diagnosis was lost in both the relapse and tertiary transplant samples. Moreover, a completely new TCRG rearrangement was identified in the patient sample at the time of relapse, and this identical rearrangement was also detectable in the tertiary transplant sample (Table 4). Thus, for 11 different antigen receptor gene rearrangements, the pattern of clonal variation from the time of diagnosis of the disease was identical after 3 passages in the NOD/SCID mice to that observed following disease progression in the clinic.

Sequence determination of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangements in patient ALL-7 at time of diagnosis, relapse, and following tertiary engraftment in NOD/SCID mice

Rearrangement . | Sequence . |

|---|---|

| IGH | |

| Diagnosis | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| Relapse | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| IGK-Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| Relapse | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| IGK-Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| Relapse | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| IGK-intron Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (VκIntron)CAGCTTTCC...............................GG...............................GGGAGCCCTA (Kde) |

| Relapse | Clonal rearrangement lost |

| NOD/SCID 3° | Clonal rearrangement lost |

| TCRG | |

| Diagnosis | (VγGCGTGGG..................................TTGTC..................................GAATTATTAT (Jγ) |

| Relapse | (VγCTGGGAC...............................TCGCCGAGGGG...............................ATTATAAGAA (Jγ) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (VγCTGGGAC...............................TCGCCGAGGGG...............................ATTATAAGAA (Jγ) |

Rearrangement . | Sequence . |

|---|---|

| IGH | |

| Diagnosis | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| Relapse | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (VH4-39)CGAGAC..................CTCTAGGATATTGTAGTGGTGGTAGCTGCTAGG..................CTGGTTCGAC (JH5) |

| IGK-Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| Relapse | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (Vκ3-20)CTCACCT.................................CC.................................AGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| IGK-Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| Relapse | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (Vκ3-20)AGCTCACCT...............................GCC...............................GGAGCCCTAGT (Kde) |

| IGK-intron Kde | |

| Diagnosis | (VκIntron)CAGCTTTCC...............................GG...............................GGGAGCCCTA (Kde) |

| Relapse | Clonal rearrangement lost |

| NOD/SCID 3° | Clonal rearrangement lost |

| TCRG | |

| Diagnosis | (VγGCGTGGG..................................TTGTC..................................GAATTATTAT (Jγ) |

| Relapse | (VγCTGGGAC...............................TCGCCGAGGGG...............................ATTATAAGAA (Jγ) |

| NOD/SCID 3° | (VγCTGGGAC...............................TCGCCGAGGGG...............................ATTATAAGAA (Jγ) |

Randomly inserted bases are shown in bold. Underlined bases present in the IGH rearranged sequence indicate a D2-15 segment. The particular V and J segments present in each rearrangement are shown in parentheses. VκIntron refers to an intronic segment of kappa light chain between Jκ5 and Cκ. Kde refers to the kappa deleting element.

In vivo responses of xenografts to vincristine, dexamethasone, or methotrexate, and their correlation with clinical outcome

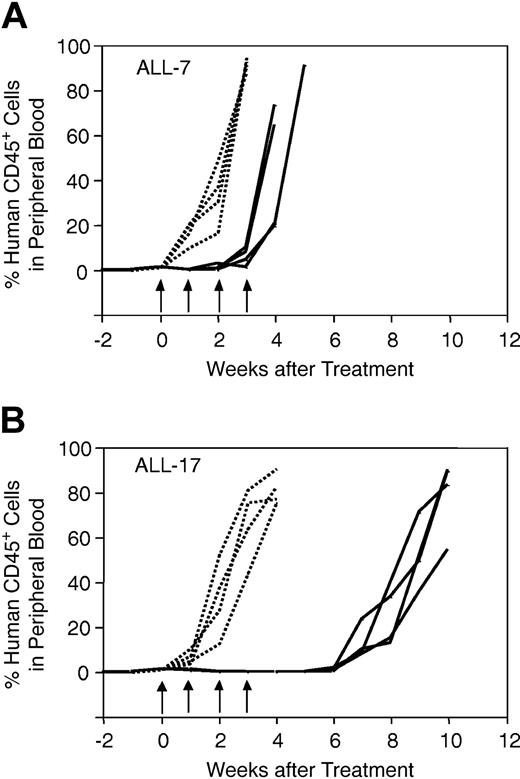

Drug dosing regimens for NOD/SCID mice treated with vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate were designed to mimic those for children with ALL.27,28 Figure 1 shows the results of a representative experiment, in which mice inoculated with ALL-7 (Figure 1A) or ALL-17 (Figure 1B) were treated with saline control (n = 4) or vincristine (n = 4). Each curve is representative of a single mouse, and the data shown in Figure 1 illustrate the high level of reproducibility within each cohort of animals. In addition, the data in Figure 1 indicate that ALL-7 was markedly less sensitive to vincristine than ALL-17. Both ALL-7 and ALL-17 were derived from patients at diagnosis (Table 1). However, patient 7 underwent an early, aggressive, and fatal relapse, while patient 17 remains in CR2 at 56 months from diagnosis despite suffering a central nervous system (CNS) relapse at 25 months.

In vivo responses of xenografts ALL-7 and ALL-17 to vincristine. Mice were inoculated with ALL-7 (A) or ALL-17 (B), monitored for engraftment, and treated with vincristine (solid lines) or saline control (dotted lines) as described in “Materials and methods.” During and following treatment, the leukemic burden was monitored by estimating the proportion of human CD45+ cells in murine peripheral blood. Each line is representative of a single mouse. Whereas saline-treated control xenografts grew at equivalent rates (A-B), ALL-7 reappeared in the peripheral blood before the final vincristine treatment (A), and ALL-17 took approximately 7 weeks from the initiation of treatment to progress (B). Data presented are from a representative experiment. Arrows indicate vincristine or saline treatment times.

In vivo responses of xenografts ALL-7 and ALL-17 to vincristine. Mice were inoculated with ALL-7 (A) or ALL-17 (B), monitored for engraftment, and treated with vincristine (solid lines) or saline control (dotted lines) as described in “Materials and methods.” During and following treatment, the leukemic burden was monitored by estimating the proportion of human CD45+ cells in murine peripheral blood. Each line is representative of a single mouse. Whereas saline-treated control xenografts grew at equivalent rates (A-B), ALL-7 reappeared in the peripheral blood before the final vincristine treatment (A), and ALL-17 took approximately 7 weeks from the initiation of treatment to progress (B). Data presented are from a representative experiment. Arrows indicate vincristine or saline treatment times.

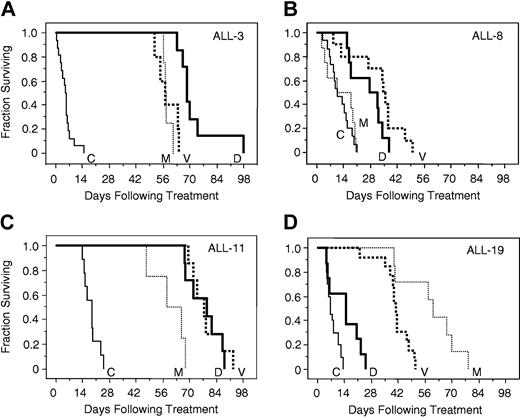

The responses of xenografts to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate were assessed, and the EFS of each mouse was calculated as described in “Materials and methods.” Complete drug response data for representative xenografts ALL-3, -8, -11, and -19, in relation to saline-treated controls, are depicted in Figure 2, which typifies the broad range of drug sensitivity of the entire group of xenografts. ALL-3 (Figure 2A) and ALL-11 (Figure 2C) were highly sensitive to all 3 drugs. In contrast, the growth of ALL-8 (Figure 2B) was unaffected by methotrexate, and only modestly retarded by dexamethasone and vincristine. Dexamethasone was able to retard the progression of ALL-19 only to a limited extent (Figure 2D), whereas this xenograft exhibited intermediate sensitivity to vincristine, and appeared at least as sensitive as ALL-3 and ALL-11 to methotrexate.

In vivo sensitivity of xenografts ALL-3, ALL-8, ALL-11, and ALL-19 to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. Mice were inoculated with ALL-3 (A), ALL-8 (B), ALL-11 (C), or ALL-19 (D), monitored for engraftment, and treated with vincristine (V; bold dotted lines), dexamethasone (D; bold lines), methotrexate (M; thin dotted lines), or saline control (C; thin lines) as described in “Materials and methods.” The EFS of NOD/SCID mice was quantified as the time taken from the initiation of treatment for the leukemic population to reach 25% in the peripheral blood, or for the animals to show evidence of leukemia-related morbidity. Each line represents the proportion of mice remaining event free over time. Xenografts ALL-3 (A) and ALL-11 (C) were highly responsive, and ALL-8 (B) relatively resistant, to all 3 drugs, whereas ALL-19 (D) was resistant to dexamethasone, of intermediate sensitivity to vincristine, and sensitive to methotrexate.

In vivo sensitivity of xenografts ALL-3, ALL-8, ALL-11, and ALL-19 to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. Mice were inoculated with ALL-3 (A), ALL-8 (B), ALL-11 (C), or ALL-19 (D), monitored for engraftment, and treated with vincristine (V; bold dotted lines), dexamethasone (D; bold lines), methotrexate (M; thin dotted lines), or saline control (C; thin lines) as described in “Materials and methods.” The EFS of NOD/SCID mice was quantified as the time taken from the initiation of treatment for the leukemic population to reach 25% in the peripheral blood, or for the animals to show evidence of leukemia-related morbidity. Each line represents the proportion of mice remaining event free over time. Xenografts ALL-3 (A) and ALL-11 (C) were highly responsive, and ALL-8 (B) relatively resistant, to all 3 drugs, whereas ALL-19 (D) was resistant to dexamethasone, of intermediate sensitivity to vincristine, and sensitive to methotrexate.

The median EFS values for mice inoculated with all 10 xenografts and treated with saline control, vincristine, dexamethasone, or methotrexate are shown in Table 5, which again illustrates the broad spectrum of xenograft drug responses.

In vivo xenograft responses to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate

. | Median EFS, d . | . | . | . | GDF value, d . | . | . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | Control . | VCR . | DEX . | MTX . | VCR . | DEX . | MTX . | Patient status . | |||||

| 2 | 18.6 | 46.0 | 50.4 | ND | 27.4 | 31.8 | ND | Deceased | |||||

| 3 | 5.2 | 57.2 | 68.6 | 57.4 | 52.0 | 63.4 | 52.2 | Alive | |||||

| 4 | 3.2 | 34.5 | ND | 56.0 | 31.3 | ND | 52.8 | Deceased | |||||

| 7 | 8.4 | 17.6 | 39.0 | 56.0 | 9.2 | 30.6 | 47.6 | Deceased | |||||

| 8 | 10.9 | 35.3 | 29.6 | 14.3 | 24.4 | 18.7 | 3.4 | Deceased | |||||

| 10 | 9.2 | 44.0 | ND | ND | 34.8 | ND | ND | Alive | |||||

| 11 | 18.8 | 77.3 | 79.0 | 62.0 | 58.5 | 60.2 | 43.2 | Alive | |||||

| 16 | 11.8 | 42.0 | 64.6 | 21.1 | 30.2 | 52.8 | 9.3 | Alive | |||||

| 17 | 6.2 | 56.1 | 38.0 | 58.7 | 49.9 | 31.8 | 52.5 | Alive | |||||

| 19 | 6.7 | 40.6 | 14.8 | 60.2 | 33.9 | 8.1 | 53.5 | Deceased | |||||

. | Median EFS, d . | . | . | . | GDF value, d . | . | . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | Control . | VCR . | DEX . | MTX . | VCR . | DEX . | MTX . | Patient status . | |||||

| 2 | 18.6 | 46.0 | 50.4 | ND | 27.4 | 31.8 | ND | Deceased | |||||

| 3 | 5.2 | 57.2 | 68.6 | 57.4 | 52.0 | 63.4 | 52.2 | Alive | |||||

| 4 | 3.2 | 34.5 | ND | 56.0 | 31.3 | ND | 52.8 | Deceased | |||||

| 7 | 8.4 | 17.6 | 39.0 | 56.0 | 9.2 | 30.6 | 47.6 | Deceased | |||||

| 8 | 10.9 | 35.3 | 29.6 | 14.3 | 24.4 | 18.7 | 3.4 | Deceased | |||||

| 10 | 9.2 | 44.0 | ND | ND | 34.8 | ND | ND | Alive | |||||

| 11 | 18.8 | 77.3 | 79.0 | 62.0 | 58.5 | 60.2 | 43.2 | Alive | |||||

| 16 | 11.8 | 42.0 | 64.6 | 21.1 | 30.2 | 52.8 | 9.3 | Alive | |||||

| 17 | 6.2 | 56.1 | 38.0 | 58.7 | 49.9 | 31.8 | 52.5 | Alive | |||||

| 19 | 6.7 | 40.6 | 14.8 | 60.2 | 33.9 | 8.1 | 53.5 | Deceased | |||||

EFS indicates event-free survival; GDF, growth delay factor; VCR, vincristine; DEX, dexamethasone; MTX, methotrexate; ND, not done.

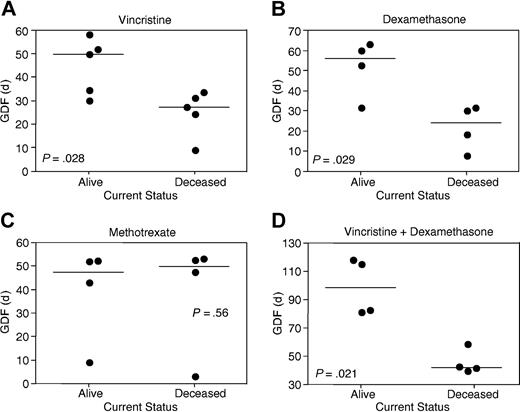

We have previously shown that, for xenografts derived from patients with ALL who had relapsed, the in vivo responses of the xenografts to vincristine correlated with the length of the respective patient's CR1.16 Of the 10 patient biopsies used to establish xenografts for the present study, the proportion of leukemic blasts in the peripheral blood of 8 patients had decreased to less than 2% within 12 days of diagnosis (ALL-8 remained at > 15%, whereas data were not available for ALL-2). For this reason, and in order to assess the relationships between xenograft drug sensitivity and patient outcome in this study, in which 3 patients remained in CR1, the xenografts were stratified into 2 quite disparate groups: those derived from patients at diagnosis who remain alive more than 4.5 years from diagnosis (ALL-3, -10, -11, -16, and -17), and those patients who had relapsed and subsequently died of their disease (ALL-2, -4, -7, -8, and -19) (Table 1). A GDF was calculated for each drug by subtracting the median EFS of saline control groups from that of drug-treated animals (Table 5). GDF values ranged from 9.2 days to 58.5 days for vincristine, 8.1 days to 63.4 days for dexamethasone, and 3.4 days to 53.5 days for methotrexate.

A comparison of GDF values stratified according to patient outcome demonstrated statistically significant differences for vincristine (P = .028; Figure 3A) and dexamethasone (P = .029; Figure 3B), but not methotrexate (P = .56; Figure 3C). Despite these correlations between disease outcome and xenograft sensitivity to vincristine and dexamethasone, there remained overlap between GDF values of the 2 patient subgroups (Figure 3A-B). The sum of vincristine and dexamethasone GDF values for individual xenografts revealed a clear separation according to patient outcome (P = .021; Figure 3D). Methotrexate GDF values for the 2 T-lineage xenografts differed significantly from the 6 B-lineage xenografts (P = .046; Table 5). When xenografts were stratified according to patient outcome, the median EFS of control saline-treated mice was not significantly different (P = .75).

Correlations between patient outcome and in vivo xenograft sensitivity to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. Xenografts were stratified according to whether patients remain alive more than 4.5 years from diagnosis or died of their disease (Tables 1 and 5). GDF values for each drug are taken from Table 5. Each data point represents an individual xenograft, with the horizontal bar depicting the median of each subgroup. Xenografts derived from the good outcome subgroup were significantly more sensitive to vincristine (A) and dexamethasone (B), but not methotrexate (C), than poor outcome cases. In panel C, the relatively resistant xenograft in each subgroup is of T lineage. The sum of vincristine and dexamethasone GDF values provided a clearer separation between patient subgroups (D) than for vincristine (A) or dexamethasone (B) alone.

Correlations between patient outcome and in vivo xenograft sensitivity to vincristine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate. Xenografts were stratified according to whether patients remain alive more than 4.5 years from diagnosis or died of their disease (Tables 1 and 5). GDF values for each drug are taken from Table 5. Each data point represents an individual xenograft, with the horizontal bar depicting the median of each subgroup. Xenografts derived from the good outcome subgroup were significantly more sensitive to vincristine (A) and dexamethasone (B), but not methotrexate (C), than poor outcome cases. In panel C, the relatively resistant xenograft in each subgroup is of T lineage. The sum of vincristine and dexamethasone GDF values provided a clearer separation between patient subgroups (D) than for vincristine (A) or dexamethasone (B) alone.

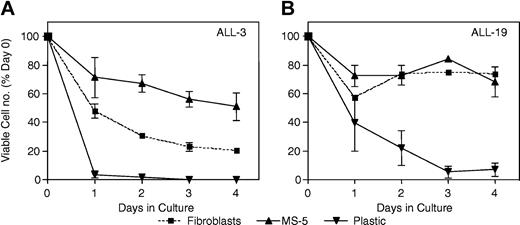

Drug responses of xenografts in vitro

Commonly used assays to estimate primary childhood ALL responses to chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro include culture on human bone marrow stroma followed by flow cytometric enumeration of viable leukemia cells,20,21 as well as nonsupported cultures assessed by the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay of mitochondrial function.25 For the former, bone marrow fibroblasts were subsequently identified as the stromal cell type that supports the survival of childhood ALL cells.22 The MS-5 cell line has also been used to support the in vitro survival of normal and malignant hematopoietic cells.23,24

The above 3 methods were compared for their ability to support the survival of 2 xenografts from separate patient outcome subgroups (ALL-3 and ALL-19). The results shown in Figure 4, in which the number of viable cells was quantified by flow cytometry, demonstrate that MS-5 cells supported the survival of ALL-3 cells more efficiently than human fibroblasts (Figure 4A), whereas the survival of ALL-19 cells was equivalent under both conditions (Figure 4B). For both xenografts, less than 10% of the number of cells originally seeded remained viable following 3 days of culture in the absence of a supporting monolayer. Given these results, MS-5–supported cultures were subsequently used to assess xenograft cell responses to vincristine and dexamethasone. Methotrexate, at concentrations up to 1 mM, was ineffective in killing xenograft cells, in agreement with published data using primary childhood ALL cells29,30 (data not shown).

Ex vivo survival of xenografts cultured under different conditions. Cells from xenograft ALL-3 (A) or ALL-19 (B) were retrieved from cryostorage (day 0) and inoculated onto a monolayer of human bone marrow fibroblasts in AIM V medium (▪), a monolayer of MS-5 cells in QBSF-60/F medium (▴), or directly into RPMI 1640 medium containing 15% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine (▾). At daily intervals thereafter, viable cells per well were enumerated by flow cytometry, as described in “Materials and methods,” and results expressed relative to a day 0 control. Overall, the survival of xenograft cells cultured on MS-5 cells was as good (ALL-19; B) or better (ALL-3; A) than xenograft cells on human fibroblasts, whereas cells without coculture rapidly lost viability. Error bars indicate SEM.

Ex vivo survival of xenografts cultured under different conditions. Cells from xenograft ALL-3 (A) or ALL-19 (B) were retrieved from cryostorage (day 0) and inoculated onto a monolayer of human bone marrow fibroblasts in AIM V medium (▪), a monolayer of MS-5 cells in QBSF-60/F medium (▴), or directly into RPMI 1640 medium containing 15% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine (▾). At daily intervals thereafter, viable cells per well were enumerated by flow cytometry, as described in “Materials and methods,” and results expressed relative to a day 0 control. Overall, the survival of xenograft cells cultured on MS-5 cells was as good (ALL-19; B) or better (ALL-3; A) than xenograft cells on human fibroblasts, whereas cells without coculture rapidly lost viability. Error bars indicate SEM.

The in vitro sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine showed a trend toward stratifying according to patient outcome (Figure 5A). However, the differences between patient outcome subgroups and cell survival at either 10 nM or 100 nM vincristine were not significant (P = .076 and P = .25, respectively; Table 6, and data not shown). Furthermore, in vivo GDF values (Table 5) did not correlate with in vitro sensitivity of the xenografts to either 10 nM vincristine (Table 6; r = 0.23; P = .53) or 100 nM vincristine (data not shown).

In vitro sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine and dexamethasone. Xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage and cultured for cell survival assays exactly as described in “Materials and methods.” Survival at each drug concentration was expressed relative to solvent-treated controls. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least 3 separate experiments. Xenografts were stratified into good (solid lines, open symbols) or poor (dashed lines, closed symbols) patient outcome subgroups, as defined in Tables 1 and 5, the legend to Figure 3, and in “In vivo responses of xenografts to vincristine, dexamethasone, or methotrexate, and their correlation with clinical outcome.” Symbols representing each xenograft are indicated. Whereas the sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine (A) showed a trend toward stratifying according to patient outcome, there were clearly 2 separate groups of dexamethasone responses (B).

In vitro sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine and dexamethasone. Xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage and cultured for cell survival assays exactly as described in “Materials and methods.” Survival at each drug concentration was expressed relative to solvent-treated controls. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of at least 3 separate experiments. Xenografts were stratified into good (solid lines, open symbols) or poor (dashed lines, closed symbols) patient outcome subgroups, as defined in Tables 1 and 5, the legend to Figure 3, and in “In vivo responses of xenografts to vincristine, dexamethasone, or methotrexate, and their correlation with clinical outcome.” Symbols representing each xenograft are indicated. Whereas the sensitivity of xenografts to vincristine (A) showed a trend toward stratifying according to patient outcome, there were clearly 2 separate groups of dexamethasone responses (B).

In vitro sensitivity of xenograft cells to vincristine and dexamethasone

. | Vincristine . | . | Dexamethasone . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | IC50 (nM) . | Cell survival at 10 nM (% of control ± SE) . | IC50 (nM) . | Cell survival at 10 nM (% of control ± SE) . | ||

| ALL-2 | < 1 | 28.7 ± 2.7 | > 1000 | 90.8 ± 1.3 | ||

| ALL-3 | 2.5 | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 9.4 | 49.4 ± 6.7 | ||

| ALL-4 | 6.3 | 42.4 ± 10.9 | 109 | 82.6 ± 1.1 | ||

| ALL-7 | 2.9 | 41.3 ± 6.7 | > 1000 | 78.7 ± 2.5 | ||

| ALL-8 | < 1 | 35.0 ± 0.8 | 105 | 94.4 ± 14.2 | ||

| ALL-10 | 1.7 | 9.8 ± 0.8 | > 1000 | 94.3 ± 2.6 | ||

| ALL-11 | 2.8 | 25.5 ± 6.4 | 3.5 | 33.5 ± 12.9 | ||

| ALL-16 | < 1 | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 4.1 | 27.0 ± 1.8 | ||

| ALL-17 | 6.9 | 48.3 ± 5.2 | 8.9 | 48.8 ± 4.8 | ||

| ALL-19 | 10.8 | 51.5 ± 6.1 | > 1000 | 106 ± 7.3 | ||

. | Vincristine . | . | Dexamethasone . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenograft . | IC50 (nM) . | Cell survival at 10 nM (% of control ± SE) . | IC50 (nM) . | Cell survival at 10 nM (% of control ± SE) . | ||

| ALL-2 | < 1 | 28.7 ± 2.7 | > 1000 | 90.8 ± 1.3 | ||

| ALL-3 | 2.5 | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 9.4 | 49.4 ± 6.7 | ||

| ALL-4 | 6.3 | 42.4 ± 10.9 | 109 | 82.6 ± 1.1 | ||

| ALL-7 | 2.9 | 41.3 ± 6.7 | > 1000 | 78.7 ± 2.5 | ||

| ALL-8 | < 1 | 35.0 ± 0.8 | 105 | 94.4 ± 14.2 | ||

| ALL-10 | 1.7 | 9.8 ± 0.8 | > 1000 | 94.3 ± 2.6 | ||

| ALL-11 | 2.8 | 25.5 ± 6.4 | 3.5 | 33.5 ± 12.9 | ||

| ALL-16 | < 1 | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 4.1 | 27.0 ± 1.8 | ||

| ALL-17 | 6.9 | 48.3 ± 5.2 | 8.9 | 48.8 ± 4.8 | ||

| ALL-19 | 10.8 | 51.5 ± 6.1 | > 1000 | 106 ± 7.3 | ||

In contrast, 2 distinct subgroups of in vitro dexamethasone sensitivity were apparent in this cohort of xenografts (Figure 5B). Moreover, 5 of 6 xenografts in the relatively dexamethasone-resistant subgroup were derived from children who subsequently died from their disease, whereas the patients who gave rise to dexamethasone-sensitive xenografts all remain alive. Relative cell survival at 10 nM (Table 6) and 100 nM (data not shown) dexamethasone differed significantly depending on patient outcome (P = .047 at both dexamethasone concentrations). Furthermore, in vivo GDF values (Table 5) exhibited a significant inverse correlation with in vitro dexamethasone sensitivity at both 10 nM (r = 0.864; P = .0057; Table 6) and 100 nM (r = 0.817; P = .013; data not shown).

The in vitro sensitivity of xenografts to dexamethasone appeared to be stable over at least 3 passages in NOD/SCID mice. Four xenografts were tested at primary, secondary, and tertiary passage and yielded 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of, respectively: 1.8 nM, 4.3 nM, and 9.4 nM (ALL-3); more than 1 μM, more than 1 μM, and more than 1 μM (ALL-7); 4.3 nM, 4.8 nM, and 4.1 nM (ALL-16); and more than 1 μM, more than 1 μM, and more than 1 μM (ALL-19).

High-resolution cell division tracking of xenograft cultures

To explain the finding that the in vitro sensitivity of xenografts correlated with patient outcome and in vivo sensitivity to dexamethasone but not vincristine, we hypothesized that xenografts proliferated to varying degrees when placed in in vitro culture on MS-5 cells. Such differences in proliferation would be expected to present a more confounding influence on the inherent sensitivity of xenografts to cell cycle–dependent agents, such as vincristine, than to drugs that effectively kill both proliferating and nonproliferating leukemia cells (eg, glucocorticoids).31 To test this hypothesis we carried out high-resolution cell division tracking of xenograft cells using the fluorescent dye CFSE.

The histograms shown in Figure 6 represent cell divisions undergone by ALL-7, -11, -17, and -19 cultured on MS-5 cells (shaded area) relative to undivided control cells (solid line). After 3 days of culture approximately 20% and 26% of ALL-7 (Figure 6A) and ALL-11 (Figure 6B) cells, respectively, remained in the undivided fraction, whereas more than 70% of ALL-17 (Figure 6C) and ALL-19 (Figure 6D) cells were undivided. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of ALL-7 (Figure 6A) cells had undergone 2 divisions by day 3, whereas varying proportions of ALL-11, -17, and -19 cells appeared only in the first generation. The net expansion (proliferation index) of xenograft cells over the 3-day incubation is shown in Figure 7, which confirms that ALL-7 and ALL-11 expanded to a considerably greater extent than ALL-17 and ALL-19, both of which underwent negligible proliferation.

High-resolution cell division tracking of xenografts in vitro. Xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage, labeled with CFSE, sorted, and cultured on MS-5 cells. After 3 days, cells were harvested and analyzed (shaded area) in relation to undivided cells equivalent to day 0 (solid line). Peak channels for undivided (U), division 1 (D1), and division 2 (D2) cells were as indicated. A significant proportion of ALL-7 cells (A) had divided twice by day 3, whereas the majority of ALL-11 cells (B) had divided only once. In contrast, only a small proportion of ALL-17 (C) and ALL-19 (D) cells had undergone a single division at this time.

High-resolution cell division tracking of xenografts in vitro. Xenograft cells were retrieved from cryostorage, labeled with CFSE, sorted, and cultured on MS-5 cells. After 3 days, cells were harvested and analyzed (shaded area) in relation to undivided cells equivalent to day 0 (solid line). Peak channels for undivided (U), division 1 (D1), and division 2 (D2) cells were as indicated. A significant proportion of ALL-7 cells (A) had divided twice by day 3, whereas the majority of ALL-11 cells (B) had divided only once. In contrast, only a small proportion of ALL-17 (C) and ALL-19 (D) cells had undergone a single division at this time.

In vitro proliferation of xenograft cells. Cell division tracking of xenograft cells was carried out exactly as described in “Materials and methods' and in the legend to Figure 6. Cells were analyzed daily after being seeded onto MS-5 cells. The proliferation index (y-axis) is plotted on a log2 scale, and represents the fold increase in cell number by proliferation only, and does not account for cell death. ALL-7 (○) underwent the greatest amount of proliferation, followed by ALL-11 (•). ALL-17 (□) and ALL-19 (▪) exhibited only a limited propensity to proliferate during this time course. For comparison, the proliferation index of the exponentially dividing T-lineage ALL CEM cell line was 2.1, 3.3, and 3.8 at 28 hours, 45 hours, and 52 hours after sorting, respectively (data not shown).

In vitro proliferation of xenograft cells. Cell division tracking of xenograft cells was carried out exactly as described in “Materials and methods' and in the legend to Figure 6. Cells were analyzed daily after being seeded onto MS-5 cells. The proliferation index (y-axis) is plotted on a log2 scale, and represents the fold increase in cell number by proliferation only, and does not account for cell death. ALL-7 (○) underwent the greatest amount of proliferation, followed by ALL-11 (•). ALL-17 (□) and ALL-19 (▪) exhibited only a limited propensity to proliferate during this time course. For comparison, the proliferation index of the exponentially dividing T-lineage ALL CEM cell line was 2.1, 3.3, and 3.8 at 28 hours, 45 hours, and 52 hours after sorting, respectively (data not shown).

Discussion

There are several reports in which either ALL cell lines10,32-39 or patient biopsies5,6,11-15,40-46 have been engrafted into immune-deficient mice. A limited number of these models have been used to monitor the efficacy of drugs used in the treatment of childhood ALL,38,40,41,45 or to test novel therapies.33-36,39-41,44-46 Nine of these studies used xenografts established as systemic disease by intravenous or intraperitoneal inoculation of leukemia cells,34-36,38-40,44-46 whereas others used localized leukemia growth following subcutaneous or intraocular injections.33,40,41 The majority of studies carried out to monitor the effects of conventional agents or novel therapies on ALL established as systemic disease used leukemia-related morbidity as the biologic end point.34-36,39,40,44 Reports where serial sampling was used to assess antileukemic effects in “real-time” are rare, and utilized one T-lineage childhood ALL cell line38 or xenografts derived from adults with ALL.45,46 To date, no studies have attempted to correlate drug sensitivity of acute leukemia xenografts with the clinical outcome of the patients from whom they were derived.

The models described herein embrace several characteristics that may be desirable for preclinical testing of new therapies, including (1) the development of a panel of continuous xenografts derived from patients who experienced diverse treatment outcomes; (2) their propagation as models of systemic disease; (3) their retention of the fundamental biologic characteristics of the original disease; (4) the ability to monitor engraftment and response to therapy in “real-time” using serial tail-vein sampling; and (5) their spectrum of sensitivity to established drugs providing an overall reflection of patient outcome.

The significant correlation between patient outcome and in vivo xenograft sensitivity to vincristine and dexamethasone might be considered surprising since treatment regimens for childhood ALL historically involve the use of at least 10 agents.1 Conversely, vincristine and dexamethasone are used in the induction treatment phase, and the initial response to therapy is considered one of the strongest predictors of outcome.1,47 Furthermore, vincristine and dexamethasone (as well as l-asparaginase and the glucocorticoid prednisolone) were the only agents out of 12 tested that predicted treatment outcome in a large series of childhood ALL biopsies subjected to in vitro drug sensitivity testing.25 The observation that the sum of vincristine and dexamethasone GDF values in our study, as well as the combination of in vitro vincristine, dexamethasone, and l-asparaginase sensitivities,25 both strengthened the correlation with clinical outcome, indicates that ex vivo responses to these agents reflect critical biologic determinants of treatment outcome.

The relative resistance of xenografts derived from T-lineage ALL (ALL-8 and ALL-16) to methotrexate compared with those from B-lineage is of interest since, unlike vincristine and dexamethasone, the methotrexate responses of our xenografts showed no stratification according to clinical outcome. Historically, a higher proportion of children with B-lineage ALL have been cured with antimetabolite-based chemotherapy regimens compared with T-lineage ALL,48,49 although comparable cure rates have been achieved with more-intensive therapy.50 This difference can be partly explained by decreased methotrexate polyglutamylation and consequent cellular retention in T-lineage ALL blasts compared with B-lineage.51,52 However, the limited number of T-lineage ALL xenografts analyzed in this study does not preclude the possibility that interindividual, rather than specific lineage, variations account for the differences in methotrexate responses between xenografts.

The in vitro sensitivity of xenografts to dexamethasone correlated significantly with their in vivo responses and clinical outcome of the patients. A similar correlation was not observed between in vitro xenograft sensitivity to vincristine, in vivo responses, and patient clinical outcome. These results are in agreement with published data that demonstrate a stronger correlation between clinical outcome and in vitro sensitivity to glucocorticoids compared with vincristine.25 We hypothesize that this difference is due to the tendency of individual xenografts to proliferate to variable extents when placed in culture. For example, ALL-7, which was the most highly vincristine-resistant xenograft in vivo (Figure 1A and Table 5), was only the fourth most vincristine-resistant xenograft in vitro (Figure 5A and Table 6), yet underwent the greatest degree of proliferation in vitro out of the 4 xenografts tested (Figure 6A and Figure 7). In further support of this hypothesis, the in vitro vincristine sensitivity of a large cohort of primary childhood ALL biopsies showed a significant correlation with proliferation index.53

Alternatively, the significant correlation between clinical outcome and in vitro sensitivity to dexamethasone, but not vincristine, may be explained by the inclusion in our study of xenografts derived from patients at relapse. Klumper et al54 have shown that primary childhood ALL biopsy specimens obtained at relapse are significantly resistant to the glucocorticoids prednisolone and dexamethasone, but not to vincristine, compared with those obtained at presentation. The corollary is that caution should be exerted when interpreting the results of in vitro cytotoxicity assays or investigations into drug resistance mechanisms using compounds that preferentially target proliferating cells, and their clinical relevance requires further verification using in vivo model systems.

An analysis of clonal antigen receptor gene rearrangements in ALL-7 and ALL-17 samples demonstrated an exact match between clonal variation observed in bone marrow samples taken at patient relapse and that seen following tertiary transplantation in mice. The appearance of a new TCRG rearrangement that was identical in both the relapse and tertiary transplant samples of ALL-7 suggests that this clonal marker identifies a subpopulation of cells that was present at low levels at the time of diagnosis. These results therefore provide strong evidence that childhood ALL cells engrafted into NOD/SCID mice afford an accurate representation of the human disease.

In summary, this report describes a highly clinically accurate experimental model for the preclinical evaluation of novel therapies for childhood ALL. The exquisite sensitivity to single-agent therapy of some of our xenografts derived from long-term survivors (eg, ALL-3, -11, -16, and -17) can be used as the benchmark when testing novel agents and therapeutic approaches against other extremely aggressive and drug-resistant xenografts derived from patients who died from their disease (eg, ALL-2, -4, -7, -8, and -19). Ultimately, the use of this experimental model may lead to the more rapid transfer of promising new agents into clinical trials for children with ALL who have relapsed with drug-resistant disease, and improved prospects for the long-term survival of these patients.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 5, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2911.

Supported by The Cancer Council, New South Wales, The Anthony Rothe Memorial Trust, and The National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

The Children's Cancer Institute Australia for Medical Research is affiliated with the University of New South Wales and Sydney Children's Hospital. The authors wish to thank Diana Waldstein for assistance in immunophenotype analysis, Laura Piras and Dr Stephen Laughton for clinical data, Leonie Gaudry for assistance in cell sorting, Prof K. John Mori (Niigata University, Japan) for providing MS-5 cells, and Immunex (Seattle, WA) for Flt-3 ligand.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal