Imatinib mesylate is a selective tyrosine receptor kinase inhibitor with activity in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.1-3 There is early evidence that it can reduce the phlebotomy requirements in patients with polycythemia vera.4 Imatinib when given in doses of 400 mg daily is generally well tolerated. Severe hepatotoxicity is rare.1,5 In the phase 3 trial of imatinib for treatment of chronic-phase CML, grades 3 to 4 transaminitis occurred in 5.1% of participants with no related deaths.5 We report here an instance of rapidly progressive, fatal acute hepatic necrosis associated with the use of imatinib.

The patient was a 61-year-old woman with polycythemia vera in spent phase/myelofibrosis. The patient was entered into a phase 2, institutional review board–approved protocol evaluating the efficacy of imatinib in bcr/abl–negative myeloproliferative disorders. Her past medical history included a history of seizures and deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism for which she had been receiving phenytoin and warfarin for more than 3 years. Baseline liver function tests were normal, with the exception of a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase (165 U/L [normal range, 38-126 U/L]). She was initiated on 400 mg per day of imatinib. After 4 weeks, she experienced grade 3 bone pain. Imatinib was held until her pain resolved, then resumed at 300 mg per day. At 3 weeks after resuming, she developed grade 2 transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase [AST], 129 U/L [normal range, 15-46 U/L], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], 145 U/L [normal range, 7-56 U/L]). She presented with abdominal pain 2 days later. Imatinib was held. Transaminases were markedly elevated (AST, 1668 U/L; ALT, 1041 U/L). Complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count (wbc) of 49 × 109/L, hematocrit of .45 (45%), and platelet count of 165 × 109/L (baseline platelet count, 432 × 109/L). Phenytoin level was subtherapeutic. International normalized ratio was 1.7. A computed tomography scan revealed mild hepatosplenomegaly. By hospital-day 2, her liver function deteriorated further (AST, 3961 U/L; ALT, 1741 U/L), and she became hypotensive and acidotic (arterial blood gas, pH 7.10; pCO2, 19 mmHg; and pO2, 122 mmHg). She was intubated and started on antibiotics. Toxicology screens, including an acetaminophen level, were negative. Ultra-sound of the liver revealed normal echotexture, patent portal vein, and normal bile ducts. Studies for bacterial and viral infections were negative. Her liver function continued to deteriorate, and she died on hospital-day 6 of uncontrollable acidosis.

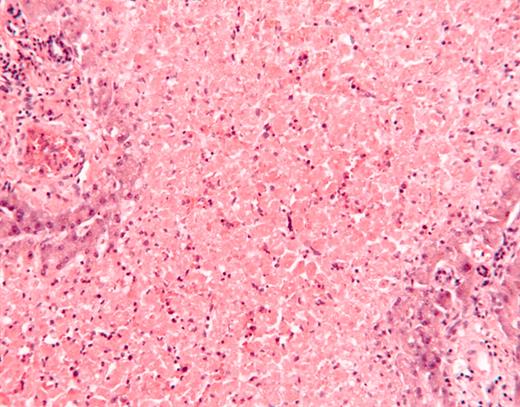

After death, the liver was enlarged (2500 g) with submassive acute hepatic necrosis (Figure 1). Fibrin thrombi were present in hepatic veins, and to a lesser extent within hepatic arterioles, and there was focal extramedullary hematopoiesis. The spleen was also enlarged (800 g) with acute geographic necrosis, rare fibrin thrombi, and extensive extramedullary hematopoiesis. Histologic examination of the lungs revealed multiple organizing microscopic pulmonary emboli. Fibrin thrombi were not detected in the other organs.

Histologic section of liver, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, showing coagulative necrosis of hepatic parenchyma with focal viable hepatocytes in a periportal distribution. Original magnification × 200.

Histologic section of liver, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, showing coagulative necrosis of hepatic parenchyma with focal viable hepatocytes in a periportal distribution. Original magnification × 200.

There has been only one previously reported death due to hepatic failure from imatinib.6 That patient was concomitantly receiving 3000 mg acetaminophen daily. We could not identify concurrent medications that are likely to have caused hepatic damage in our patient. A comprehensive toxicology screen was negative, she denied use of herbs, and her phenytoin level was subtherapeutic. Additionally, though polycythemia vera itself can be associated with hepatic failure, this is usually associated with splenectomy or Budd-Chiari syndrome, neither of which is relevant to our patient.7-10

One other group has described pathologic findings in a patient with imatinib-associated hepatotoxicity. They found focal hepatic necrosis compatible with the regression phase of viral hepatitis.11 In contrast, our patient was found to have hepatic necrosis with microthrombi within the vasculature of the liver, spleen, and lungs. Thrombi were not present in other organs, such as the kidneys, arguing against disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. The microthrombi present were more likely to have been the result of the hepatic necrosis rather than the cause, but the latter cannot be definitively ruled out. Even if the thrombi resulted from hepatic necrosis, however, the number of pulmonary emboli present suggests an underlying prothrombotic state. Notably, the patient had remained free of any new vascular events in the 3 years since treatment with warfarin. The most recent intervention was initiation of imatinib; therefore, we must presume this relates directly to her hepatic failure and subsequent death. We are intrigued by the observation that polycythemia vera, in contrast to CML, is associated with thrombosis of large vessels.12 We speculate that the mechanism by which imatinib caused hepatic necrosis in our patient is related to exacerbation of the underlying prothrombotic tendency of polycythemia vera, which is not present in CML. As the clinical use of imatinib increases, it will be critical to further define the pathophysiology of this life-threatening complication.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal