Abstract

Liver failure is often accompanied by cognitive impairment and coma, a syndrome known as hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The administration of flumazenil, a benzodiazepine (BZ) antagonist, is effective in reversing the symptoms of HE in many patients. These clinical observations gave rise to notions of an endogenous BZ-like mechanism in HE, but to date no viable candidate compounds have been characterized. We show here that the hemoglobin (Hb) metabolites hemin and protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) interact with the BZ site on the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor and enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission in a manner similar to diazepam and zolpidem. This finding suggests that hemin and PPIX are neuroactive porphyrins capable of acting as endogenous ligands for the central BZ site. The accumulation of these porphyrins under pathophysiologic conditions provides a potentially novel mechanism for the central manifestations of HE.

Introduction

Liver disease and cirrhosis account for more than 6% of deaths for individuals between the ages of 45 to 54 years, making it the fourth leading cause of death within this age group in the United States.1 Associated complications such as hepatic encephalopathy (HE) therefore constitute a significant public health problem. The mechanism of HE is not clear, although it has been known for some time that treatment with benzodiazepine (BZ) antagonists ameliorates symptoms of cognitive impairment in many HE patients.2,3 BZs, which are used clinically as sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics, bind to receptors in the central nervous system (CNS),4,5 where they act at an allosteric site to promote the actions of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Numerous reports have described the presence of BZ-like compounds in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of HE patients,6-10 and in animal models of HE,7,9,11 but these substances have been incompletely characterized. Nevertheless, the successful use of the BZ antagonist flumazenil in HE patients2,3 has promoted the concept that a circulating endogenous BZ-like substance is involved in HE.9,10,12

Certain metabolites of hemoglobin (Hb) have been shown to bind with high affinity to peripheral BZ receptors13 (proteins that share some ligand-binding characteristics with the central BZ receptors). These compounds have never been measured in HE but are known to rise into the low micromolar range in porphyrias, in which similar cognitive deficits are observed.14 In the present study, we report a novel action of the Hb metabolites hemin and protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) on central neurons, and describe in detail their effects on neuronal, synaptic, and recombinant GABAA receptors (GABAA-R).

Materials and methods

Cell culture, transfection, and mutagenesis

Cortical neurons were dissected from day 20 (e20) C57 mouse embryos and maintained as previously outlined.15 Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK) 293 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were passaged weekly and cultured on poly-D-lysine–coated coverslips (Sigma, St Louis, MO).16 The pCIS 2.0-plasmid vector was used for expression of all subunits as previously described,16 and 2.5 μg of each subunit cDNA was used for the transient expression of receptors using the calcium phosphate method.17 (The α1 and γ2s subunits were human cDNA, and the β2 cDNA was of rat origin.) The α1 His101Arg mutation was introduced using the QuickChange Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with commercially generated primers (Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA). Positive clones containing the mutation were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Cornell University DNA Sequencing Service, Ithaca, NY).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch recordings were performed on e20 cultured mouse cortical neurons and on HEK 293 cells.15,16 Miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) of cultured neurons were recorded as described.18

Cells were voltage-clamped at –60 mV with an Axopatch 1-C (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) for all experiments. All compounds were dissolved daily into the appropriate extracellular solution and rapidly applied16 (∼50 ms) to cells.

Flumazenil (Sigma) was prepared as a 10-mM stock solution in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Fluka BioChemika, La Jolla, CA) and coapplied with modulators and agonist. Stock solutions of hemin (Sigma) were prepared in 10 mM Tris-HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) and 10 mM solutions of PPIX (Sigma) in DMSO. GABA was obtained from Sigma.

Concentration-response data were fitted (GraphPad Prism 3; GraphPad, San Diego, CA) using the following equation: I/Imax = 100[L]nH/([L]nH+ (EC50) nH), where I/Imax is the maximum possible response, EC50 is the concentration eliciting half of the maximum response, [L] is the GABA or porphyrin concentration, and nH is the Hill coefficient. Analyses of mIPSCs were carried out using MiniAnalysis 5.5 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) and Prism 3 (GraphPad). Weighted decay time constants (τw) were calculated as follows: τw = (A1 × τ1 + A2 × τ2)/(A1 + A2).18 The relative frequency of mIPSC events was analyzed by randomly selecting events from 5 s bins. Statistical analyses were carried out using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey multiple comparisons test. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Hb metabolites increase GABA responses in neurons

In initial experiments, we studied the actions of hemin and PPIX using whole-cell recordings from cultured mouse cortical neurons. Currents elicited by GABA were of maximal amplitude (Imax)– 1.4 ± 0.2 nanoamps (nA) (n = 121 cells), with a concentration required for 50% of the maximal response (EC50) for GABA of 14.0 ± 0.9 μM (n = 54 cells). Application of low micromolar concentrations of hemin enhanced responses to GABA (Figure 1A), up to a maximum of 70% with an EC50 for hemin of 2.5 ± 0.9 μM (Figure 1B; 10 observations on 8-20 cells). This potentiating effect of hemin was abolished in the presence of 4 μM flumazenil (Figure 1C; 8 observations on 4-7 cells, P < .01). This concentration of the BZ antagonist completely blocked the action of diazepam and zolpidem (0.01-3 μM) (data not shown). PPIX also enhanced responses to GABA (8 observations on 5-12 cells)—and the effect of PPIX was also blocked by flumazenil (Figure 1C; 6 observations on 9-12 cells, P < .02).

Hemin enhances GABA responsiveness in cultured mouse cortical neurons. (A) Hemin (2 and 10 μM) increases the amplitude of submaximal responses to EC20 concentrations of GABA in one neuron. Horizontal bars indicate GABA (short) and modulator (long) application in all figures. Scale bar, 1 nA and 4 s. (B) Concentration-response curve for hemin potentiation of the GABA response. Points (□) are plotted means ± SEM. Where not shown, errors were smaller than the size of the symbols. (C) Effects of hemin (*P < .01) and PPIX (†P < .02) on GABA responses of cultured neurons in the absence and presence of flumazenil. Error bars indicate SEM.

Hemin enhances GABA responsiveness in cultured mouse cortical neurons. (A) Hemin (2 and 10 μM) increases the amplitude of submaximal responses to EC20 concentrations of GABA in one neuron. Horizontal bars indicate GABA (short) and modulator (long) application in all figures. Scale bar, 1 nA and 4 s. (B) Concentration-response curve for hemin potentiation of the GABA response. Points (□) are plotted means ± SEM. Where not shown, errors were smaller than the size of the symbols. (C) Effects of hemin (*P < .01) and PPIX (†P < .02) on GABA responses of cultured neurons in the absence and presence of flumazenil. Error bars indicate SEM.

Hb metabolites enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission

Sedative-hypnotic BZs prolong inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) mediated by synaptic activation of GABAA-R.18,19 We therefore examined the effects of the Hb metabolite hemin on mIPSCs recorded from cultured cortical neurons. In the presence of hemin, we observed an increase in the amplitude and duration of mIPSCs (Figure 2A-B). The decay time (expressed as τw – the weighted decay time constant18 ) for the mIPSCs increased from 22.5 ± 0.8 ms (n = 20 cells) to 41 ± 1 ms (n = 20 cells) in 5 μM hemin (Figure 2C, P < .01). The amplitude of the mIPSCs also increased by approximately 110%, from 58 ± 5 picoamps (pA) (n = 20 cells) under control conditions, to 126 ± 7 pA (n = 20 cells) following exposure to 5 μM hemin (Figure 2D, P < .01). In addition, we observed an apparent increase in the frequency of mIPSCs in the presence of hemin (controls, 1.4 ± 0.1 events/per 5 s epoch [n = 20 cells]; 5 μM hemin, 3.7 ± 0.3 events/per 5 s epoch [n = 20 cells; P < .01]) (Figure 2A,E). These effects are similar to those seen with BZs18,19 and were prevented by pretreatment with 4 μM flumazenil (data not shown).

Hemin enhances synaptic inhibition in cultured mouse cortical neurons. (A) Spontaneous mIPSCs from an individual neuron in the presence (bottom trace) and absence (top trace) of 5 μM hemin. Scale bar, 25 pA and 1 s. (B) Superimposed mIPSC averages from single neurons (10 events), control (black), and 5 μM hemin (red). Scale bar, 10 pA and 40 ms. (C) mIPSCs are prolonged (τw)by 5 μM hemin (▪) (*P < .01). (D) Hemin (▪) increases the amplitude of mIPSCs (*P < .01). (E) Hemin (▪) increases the frequency of mIPSCs (*P < .01). □ indicates control.

Hemin enhances synaptic inhibition in cultured mouse cortical neurons. (A) Spontaneous mIPSCs from an individual neuron in the presence (bottom trace) and absence (top trace) of 5 μM hemin. Scale bar, 25 pA and 1 s. (B) Superimposed mIPSC averages from single neurons (10 events), control (black), and 5 μM hemin (red). Scale bar, 10 pA and 40 ms. (C) mIPSCs are prolonged (τw)by 5 μM hemin (▪) (*P < .01). (D) Hemin (▪) increases the amplitude of mIPSCs (*P < .01). (E) Hemin (▪) increases the frequency of mIPSCs (*P < .01). □ indicates control.

Hb metabolites bind to GABAA-R

In order to investigate the actions of hemin and PPIX on GABAA-R at the molecular level, we studied transiently expressed GABAA-R consisting of α1β2γ2s subunits—the most widely expressed subunit combination found in the mammalian brain.20 The use of recombinant GABAA-R allowed us to analyze the effects of subunit composition and mutagenesis on receptor modulation by these neuroactive porphyrins.

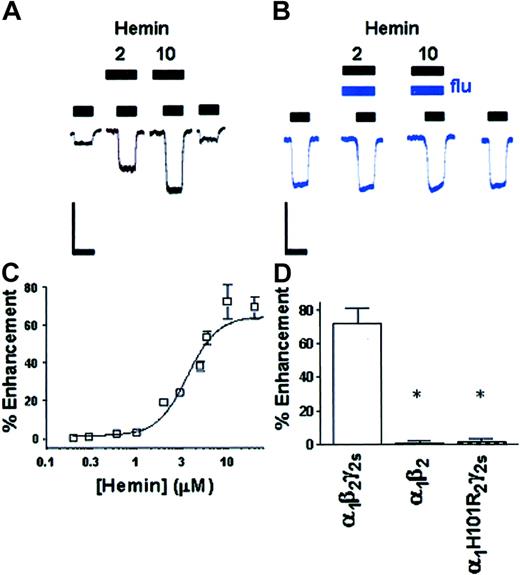

Maximal currents elicited by GABA in recombinant wild-type α1β2γ2s HEK 293 cells were –1.5 ± 0.1 nA (n = 106 cells) in amplitude, with an EC50 for GABA of 17 ± 1 μM (n = 62 cells). In HEK 293 cells expressing the wild-type α1β2γ2s GABAA-R, as with native receptors, hemin enhanced responses to submaximal concentrations of GABA (Figure 3A), an effect that was completely blocked in the presence of 4 μM flumazenil (Figure 3B). Dose-effect curves constructed for hemin revealed a maximal potentiating effect of 72 ± 9% (Figure 3C), an EC50 value for hemin of 3.6 ± 0.1 μM (16 observations on 9-30 cells), and a saturating effect observed near the 10-μM hemin level (Figure 3A). Exposure of these receptors to PPIX yielded similar results to those with hemin, with a maximal potentiating effect of 94 ± 10%, an EC50 value for PPIX of 2.3 ± 0.1 μM, and a saturating effect observed near the 5-μM PPIX level (17 observations on 8-25 cells).

Hemin interacts with the BZ site of the GABAA-R. (A) Hemin (2 and 10 μM) enhances submaximal GABA currents in one HEK 293 cell expressing α1β2γ2s GABAA-R. (B) Potentiation of GABA responses by hemin (2 and 10 μM) in one recombinant α1β2γ2s HEK 293 cell is blocked by coapplication of flumazenil (4 μM). Scale bars, 1 nA and 4 s. (C) Dose dependence of hemin potentiation in α1β2γ2s GABAA-R. Points (□) are plotted as means ± SEM. Where not shown, errors were smaller than the size of the symbols. (D) Enhancement of the GABA response by hemin in recombinant α1β2γ2s, α1β2 (*P < .01), and α1His101Argβ2γ2s (*P < .01) receptors.

Hemin interacts with the BZ site of the GABAA-R. (A) Hemin (2 and 10 μM) enhances submaximal GABA currents in one HEK 293 cell expressing α1β2γ2s GABAA-R. (B) Potentiation of GABA responses by hemin (2 and 10 μM) in one recombinant α1β2γ2s HEK 293 cell is blocked by coapplication of flumazenil (4 μM). Scale bars, 1 nA and 4 s. (C) Dose dependence of hemin potentiation in α1β2γ2s GABAA-R. Points (□) are plotted as means ± SEM. Where not shown, errors were smaller than the size of the symbols. (D) Enhancement of the GABA response by hemin in recombinant α1β2γ2s, α1β2 (*P < .01), and α1His101Argβ2γ2s (*P < .01) receptors.

We next expressed receptors without the γ2s subunit (α1β2), which has been reported to be essential for the actions of BZs at GABAA-R.21 Receptors consisting of only α1β2 subunits responded to GABA by producing an average Imax of –780 ± 59 pA (n = 33 cells) and an EC50 of 15 ± 1 μM (n = 33 cells), but were insensitive to potentiation by the blood porphyrins hemin and PPIX at concentrations up to 100 μM (Figure 3D; 7 observations on 4-11 cells, P < .01). We then studied the effects of a point mutation (in the α1 subunit), His101Arg (α1His101Arg), which has been shown to render GABAA-R insensitive to BZs.22,23 Recombinant α1His101Argβ2γ2s GABAA-R responded to GABA by producing an average Imax of –1.4 ± 0.2 nA (n = 24 cells) and an EC50 of 18 ± 3 μM (n = 24 cells), and as was seen with the α1β2 GABAA-R, the effects of hemin and PPIX were abolished at concentrations up to 100 μM (Figure 3D; 5 observations on 5-12 cells, P < .01).

Hemin contains iron coordinated by 4 pyrrole rings, so we investigated the potential effects of FeCl2 and FeCl3 on the GABAA-R. Application of divalent iron, FeCl2 or trivalent iron, FeCl3 (0.1-100 μM; 7 observations on 4-10 cells) had no effect on GABAA-R function. In contrast, the trivalent ion Gd3+ (Narahashi et al24 ) produced a large enhancement of GABA responses, but this effect was not blocked by flumazenil (data not shown). Hb (1-500 μM) produced no enhancement of the GABA response at recombinant GABAA-R, and since bilirubin levels are increased in HE patients we also applied it within a physiologically relevant concentration range (300-700 μM)25 and observed no potentiation (data not shown).

Discussion

The data presented here show that both metabolites of Hb are neuroactive substances within the micromolar concentration range. The lack of activity of Fe2+ or Fe3+ ions on the GABAA-R indicates that the effects of hemin and PPIX are a property of the porphyrin structure and not solely caused by release of metal ions. In addition, the actions of these porphyrins at the GABAA-R are consistent with a BZ-like depressant action on the CNS.4,5 Porphyrin modulation of the GABAA-R is contingent upon the presence of the γ2s subunit, blocked by flumazenil and abolished by the His101Arg mutation in the α1 subunit, properties that are all consistent with a BZ-like action of these compounds at the GABAA-R.

Several authors have proposed a contribution of endogenous BZ-like compounds to the complex neurologic problems associated with HE,6-10 and flumazenil is often effective in the relief of HE symptoms.2,3 The BZ-like actions of both hemin and PPIX in vitro suggest that these porphyrins may function as endogenous BZs8,26 in vivo, and thus contribute to the neurologic perturbations observed in HE patients. It is of interest to note that not all HE patients respond favorably to treatment with flumazenil,2 but that a large majority of those with considerable gastrointestinal bleeding do so.27 A role for circulating metabolites in the CNS symptoms observed in HE patients is also suggested by the neurologic improvements seen in these patients following dialysis.28,29

An increase in circulating Hb metabolites may occur in HE because of elevated hemolysis30 combined with increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier,31 and this may lead to an accumulation of hemin and PPIX in the CSF. We suggest that such a pathologically high level of porphyrins could produce significant CNS effects. Serum porphyrin levels are normally less than 0.1 μM, but have been reported to exceed 20 μM14 in chronic porphyrias, disorders with strikingly similar hepatocellular pathology and neurologic symptoms to HE.14

The data presented here are consistent with the idea that a significant component of the cognitive symptoms in HE patients may be mediated by neuroactive hb metabolites, via BZ-like modulation of GABAA-R. The measurement of serum porphyrin levels in these patients will aid in the evaluation of this hypothesis regarding the etiology of HE. The BZ-like nature of the porphyrin effect also raises the possibility that flumazenil may be useful in the management of CNS symptoms associated with the porphyrias. The identification of hemin and PPIX as allosteric modulators of the GABAA-R demonstrates a novel neuroactive property of circulating hb metabolites, and adds to the striking diversity of ligands at the central BZ receptor site.4,5 Neuroactive porphyrins may represent a new starting point for the future development of novel sedative, hypnotic, and anxiolytic compounds.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, April 24, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0739.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr Ajay Verma and Dr Andrew Jenkins for helpful discussion, and Jill Kelley for technical assistance.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal