Recently, it has been demonstrated that macrophage inflammatory protein 1- alpha (MIP-1α) is crucially involved in the development of osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma (MM). The current study was designed to determine the direct effects of MIP-1α on MM cells. Thus, we were able to demonstrate that MIP-1α acts as a potent growth, survival, and chemotactic factor in MM cells. MIP-1α–induced signaling involved activation of the AKT/protein kinase B (PKB) and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. In addition, inhibition of AKT activation by phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase (PI3-K) inhibitors did not influence MAPK activation, suggesting that there is no cross talk between MIP-1α–dependent activation of the PI3-K/AKT and extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. Our data suggest that besides its role in development of osteolytic bone destruction, MIP-1α also directly affects cell signaling pathways mediating growth, survival, and migration in MM cells and provide evidence that MIP-1α might play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of MM.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by the clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow. Bone destruction is a common manifestation of the disease and results from increased osteoclastic bone resorption and decreased bone formation. The development of lytic bone lesions occurs only in areas of bone adjacent to myeloma cells,1 suggesting that lytic lesions result from local overproduction of osteoclast stimulatory factors, which are secreted by MM cells, bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), or both. One of these factors responsible for osteoclastic bone resorption might be macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1α), a low molecular weight chemokine that belongs to the RANTES (regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted) family of chemokines and binds to receptors CCR1, CCR5, and CCR9. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that MIP-1α is able to induce osteoclast (OCL) formation in marrow cultures2 and is chemotactic for rat OCLs.3 Choi et al4 have shown that MIP-1α is an OCL-stimulating factor in human marrow cultures and is overexpressed in patients with MM, but not in healthy individuals. Thus, blocking of MIP-1α using neutralizing antibodies inhibits the osteoclast stimulatory factor (OSF) activity in the bone marrow plasma from patients with MM.4 Furthermore, inhibition of MIP-1α using antisense blocks bone destruction in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice.5 These data suggest that MIP-1α may play a major role in the microenvironment by mediating bone destruction in patients with MM.

So far, several cytokines from the bone marrow microenvironment have been implicated in contributing to the development of MM. Especially, interleukin 6 (IL-6) has been frequently suggested to be crucial for the pathogenesis of MM and has been shown to act as an autocrine, paracrine growth, and survival factor.6-8 However, treatment of MM patients with neutralizing anti–IL-6 monoclonal antibody (mab) has only shown marginal effects,9,10leading to the following conclusions: (1) IL-6 levels in bone marrow microenvironment might not be amenable to the blocking effect of the neutralizing mab, (2) other soluble factors might contribute to the pathogenesis of MM, and (3) direct cell-cell interactions11 between MM and BMSCs might be of superior relevance. On the basis of the above-presented evidence that MIP-1α plays an important role in the bone resorption process typical of MM, we addressed the issue whether MIP-1α has direct effects on MM cells. Indeed, we were able to show that not only MIP-1α but also its receptor CCR5 are expressed by MM cells and that MIP-1α triggers activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway leading to proliferation, chemotaxis, and protection against apoptosis, suggesting a major role for MIP-1α in the pathophysiology of MM.

Material and methods

Cells and culture conditions

Dexamethasone (Dex)–sensitive human MM cell line (MM.1S) was kindly provided by Dr Steven Rosen (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). XG-1 cells were obtained from Dr Regis Bataille (University Hospital, Nantes, France), INA6 from Dr Martin Gramatzki (University of Erlangen, Germany), BJAB from Dr Peter Daniel (Max-Delbrück-Centrum [MDC], Berlin, Germany), and OPM2 and H929 from Dr Michael Kuehl (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD).12 ARH77, U266, IM9, and RPMI-8226 myeloma cells were obtained from the American Tissue Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Jurkat, Raji, and Nalm6 were purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). Because extended passaging in culture can affect sensitivity of cells toward drug-induced apoptosis, we also examined the activity of MIP-1α on cells recently isolated from a myeloma patient (pat MM) and growing as a cell line. These patient myeloma cells (96% CD38+, CD45RA−) were purified from patient bone marrow (BM) samples, as previously described13 and were obtained from Dr Kenneth Anderson (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). Surface marker analysis showed the expression of CD38, CD138, CD56, and CD79a.

MM cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mMl-glutamine (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), 25 U/mL penicillin, and 25 ng/mL streptomycin (GIBCO).

Proliferation assays

MM cells were incubated at a concentration of 3 × 105/mL for 48 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2 in 96-well culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in the presence of media supplemented with 2.5% FBS, MIP-1α (0, 10, 100, 500 ng/mL) with or without drug treatment. Drug treatment included 50 μM MEK1 inhibitor PD 98050, 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex), 10 μM melphalan (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and 5 μg/mL recombinant IL-6R antagonist SANT7 expressed in Escherichia coli14 (SANT7 was generously provided by Gennaro Ciliberto and Rocco Savino, IRBM, Rome, Italy). DNA synthesis was measured by [3H]thymidine (NEN Products, Boston, MA) incorporation. Cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine (0.0185 MBq/well [0.5 μCi/well]) during the last 8 hours of culture, harvested onto glass fiber filter mats (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD) with an automatic cell harvester (Tomtec Harvester 96 Mach III, Hamden, CT), and counted using Wallac Trilux Betaplate scintillation counter. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunoblotting

MM.1S or pat MM cells were pretreated with one of the PI3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin (1 μM) or LY 294002 (50 μM) or with the MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) for 1 hour prior to the addition of 100 ng/mL MIP-1α (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were harvested, washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane], 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM Na-pyrophosphate, 1% triton, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and protein inhibitor cocktail; Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). Cell lysates were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to Hybond C super filters (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The blots were probed with the following antibodies: antiphospho-ERK1,2(p44,42), antiphospho-AKT (Ser473), anti-AKT, antiphospho-FKHR (Ser256) (Cell Signaling), and immune complexes were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham).

Analysis of MIP-1α secretion and MIP-1α–induced secretion of other cytokines

Protein expression of MIP-1α was determined by standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Supernatants from the indicated cell lines were collected from equal numbers of cells 1 × 106 cells/mL cultured in 2.5% FBS for 48 hours and analyzed for the presence of MIP-1α by ELISA. MIP-1α concentrations were determined using a human MIP-1α immunoassay (Quantikine; R&D, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

To assess whether MIP-1α is able to induce secretion of other cytokines in MM1.S cells we treated 1 × 106 cells/mL for 48 hours with 100 ng/mL MIP-1α in RPMI medium containing 2.5% FBS. Supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interferon γ (IFN-γ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), and MIP-1β by Bio-Plex Cytokine Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transwell migration assay

MIP-1α–induced cell migration was determined using a modified Boyden chamber with 8-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane separating the 2 chambers (Costar). The cells were starved in media with 5% FBS for 12 hours and then added onto the upper chamber membrane precoated with 10 ng/mL fibronectin. MIP-1α (0.5-500 ng/mL) in RPMI 1640 media with 0% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Five hours later cells, which had migrated into this chamber, were enumerated using a Coulter counter ZBII (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). Fold increase in MIP-1α–specific migration was calculated by comparing the cells in the chamber following MIP-1α treatment, relative to the cells, which had spontaneously migrated in the absence of MIP-1α.

Flow cytometric analysis of CCR1, CCR5, and CCR9 expression

Staining for CCR1, CCR5, and CCR9 expression was performed as recommended by the manufacturer of the anti-CCR1, -CCR5, -CCR9 mabs (Clone 145-P, Clone 182-F, and Clone 179-P; R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, 105 MM1.S cells or pat MM cells were stained with 10 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled CCR1, CCR5, CCR9 mabs or an FITC-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) mab (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Prior to staining cells were pretreated by microwaving in 2% paraformaldehyde. Thereafter, cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Samples were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Analysis of results was done using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Diego, CA).

Detection of MIP-1α mRNA by RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from MM1.S, INA-6, U266, and RPMI-8226 cell lines using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription (RT) of mRNA and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out in Titan One Tube RT-PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The conditions for amplification were as follows: 30 minutes at 50°C, 2 minutes at 94°C, 30 cycles of 10 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 58°C, 45 seconds at 68°C followed by extension for 7 minutes at 68°C. Primer sequences were as follows: MIP-1α, 5′-GCTGACTACTTTGAGACGAGC-3′(sense), 5′-CCAGTCCATAGAAGAGGTAGC-3′(antisense); glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 5′-GACATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAA-3′ (sense), 5′-TGTCATACCAGGAAATGAGC-3′ (antisense). The primer pair GAPDH was used as an internal control. PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gel and photographed.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of differences observed in MIP-1α–treated versus control cultures was determined by means of an unpaired Student t test. P < .05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Expression of MIP-1α and its receptor on MM cell lines

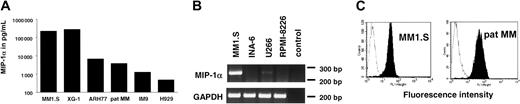

To assess whether different MM cell lines secrete MIP-1α protein, cells were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL in RPMI 1640 with 2.5% FBS. MIP-1α secretion was measured in 48-hour culture supernatants by ELISA. MIP-1α secretion was detectable in XG-1, MM1.S, ARH 77, IM9, H929 cells, and the recently established pat MM cell line. RPMI-8226, U266, and INA6 did not secrete MIP-1α. Secretion of MIP-1α after 48 hours of cell culture ranged from 450 pg/mL in H929 up to very high levels of 262 ng/mL in MM1.S (Figure 1A). To confirm that RPMI-8226, U266, and INA6 did not secrete MIP-1α, we analyzed MIP-1α mRNA expression by RT-PCR. MIP-1α mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR neither in RPMI-8226 nor in INA-6. For U266 we detected only a very faint band. RT-PCR results are shown in Figure 1B.

MM cell lines express MIP-1α and MIP-1α receptor CCR5.

(A) MM1.S, XG-1, ARH77, pat MM, IM9, and H929 cells secrete MIP-1α. Supernatants were collected after 48 hours in culture and analyzed for MIP-1α by ELISA. (B) Equal amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed to generate cDNA that was used for PCR analysis of MIP-1α mRNA expression in cell lines that were negative in MIP-1α ELISA. MM1.S served as a positive control. (C) CCR5 expression was studied by flow cytometry. MM1.S cell line and pat MM cells were stained with an FITC-labeled anti-CCR5 mab (filled histogram) or an FITC-conjugated IgG2b-isotype control mab (open histogram).

MM cell lines express MIP-1α and MIP-1α receptor CCR5.

(A) MM1.S, XG-1, ARH77, pat MM, IM9, and H929 cells secrete MIP-1α. Supernatants were collected after 48 hours in culture and analyzed for MIP-1α by ELISA. (B) Equal amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed to generate cDNA that was used for PCR analysis of MIP-1α mRNA expression in cell lines that were negative in MIP-1α ELISA. MM1.S served as a positive control. (C) CCR5 expression was studied by flow cytometry. MM1.S cell line and pat MM cells were stained with an FITC-labeled anti-CCR5 mab (filled histogram) or an FITC-conjugated IgG2b-isotype control mab (open histogram).

Expression of MIP-1α receptors CCR1, CCR5, and CCR9 was analyzed in MM1.S cell line as well as in pat MM cells by flow cytometry. Expression of CCR5 receptor was detected in both cell lines (Figure1C), whereas we were not able to detect CCR1 and CCR9 receptors (data not shown).

MIP-1α is a growth factor for human MM cells

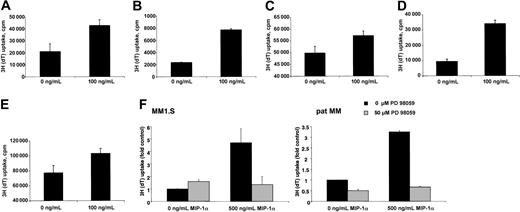

To address the question of whether MIP-1α was biologically significant in terms of tumor cell growth, we analyzed the mitogenic effect of MIP-1α on in vitro growth of MM cell lines. Cells were cultured with 2.5% FBS either in the presence or absence of MIP-1α for 48 hours and then pulsed with [3H]thymidine. Compared with controls, addition of MIP-1α resulted in a statistically significant increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation in MM1.S, pat MM, H929, INA-6, and OPM2 cells (Figure 2A-E).

We further wanted to exclude that effects of MIP-1α on proliferation are not mediated by the induction of other cytokines, for example, IL-6 secretion. Therefore, we treated MM1.S cells for 48 hours with MIP-1α and analyzed supernatants with the Bio-Plex Cytokine Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This assay is able to analyze 17 different cytokines from the same supernatant. Our analyses included IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, G-CSF, MCP-1, and MIP-1β. None of these cytokines were induced by the treatment of MIP-1α. Especially, there was no difference in IL-6 secretion in untreated MM1.S (29.5 pg/mL) and treated MM1.S (34.3 pg/mL) cells.

To assess the signaling pathways contributing to the mitogenic effect of MIP-1α, we studied the effect of MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 on MIP-1α–induced proliferation. Treatment with MEK1 inhibitor significantly inhibited the MIP-1α–induced proliferation in both, MM1.S and pat MM cells (Figure 2F).

MIP-1α induces proliferation of MM cell lines, which can be inhibited by MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059.

(A) MM1.S, (B) pat MM, (C) H929, (D) INA-6, and (E) OPM2 cells were incubated for 48 hours without or with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL). Data represent means ± SDs for at least triplicate samples. Statistical significance is for MM1.S, P = .010; pat MM,P = .000 28; H929, P = .0008; INA-6,P < .01; and OPM2, P = .0007. (F) MM1.S and pat MM cells were incubated for 48 hours with or without MIP-1α (500 ng/mL). Untreated and treated MM cells were incubated with MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM). Incubation with MIP-1α led to a significant increase of proliferation (MM1.S, P = .03; pat MM, P = .0002) that could be abrogated by PD 98059 treatment. Data represent means ± SDs for triplicate samples.

MIP-1α induces proliferation of MM cell lines, which can be inhibited by MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059.

(A) MM1.S, (B) pat MM, (C) H929, (D) INA-6, and (E) OPM2 cells were incubated for 48 hours without or with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL). Data represent means ± SDs for at least triplicate samples. Statistical significance is for MM1.S, P = .010; pat MM,P = .000 28; H929, P = .0008; INA-6,P < .01; and OPM2, P = .0007. (F) MM1.S and pat MM cells were incubated for 48 hours with or without MIP-1α (500 ng/mL). Untreated and treated MM cells were incubated with MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM). Incubation with MIP-1α led to a significant increase of proliferation (MM1.S, P = .03; pat MM, P = .0002) that could be abrogated by PD 98059 treatment. Data represent means ± SDs for triplicate samples.

Because MM1.S is a Dex-sensitive cell line and Moalli et al15 could show that Dex induces apoptosis in MM1.S cells, we examined in a next step whether MIP-1α is able to prevent MM1.S cells from Dex-induced inhibition of proliferation. We confirmed that MM1.S cells are sensitive to Dex with an inhibition of proliferation from 21 197 ± 1767cpm to 5648 ± 472 cpm measured by thymidine incorporation under treatment of 1 μM. Even at very high concentration of MIP-1α up to 500 ng/mL, MIP-1α was not able to overcome Dex-induced effects. MM1.S cells were also sensitive to melphalan. At a concentration of 10 μM we observed an inhibition of proliferation from 21 197 ± 1767 cpm to 193 ± 47 cpm also measured by thymidine incorporation. Concomitant treatment with MIP-1α again at very high concentrations of 500 ng/mL was not able to prevent cells from inhibition of proliferation.

Treatment of MM1.S cells with recombinant IL-6R antagonist SANT7 (5 μg/mL) had no influence on proliferation with or without MIP-1α. This result is in accordance with the fact that MM1.S is completely IL-6 independent.

To assess whether the effects of MIP-1α are unique to myeloma we investigated MIP-1α–induced proliferation in nonmyeloma cells like Nalm 6, Raji, BJAB (B-cell lines), and Jurkat (T-cell line). MIP-1α did not induce proliferation in these cell lines (data not shown).

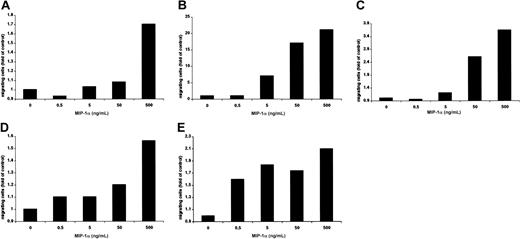

MIP-1α induces migration of MM cells

Using a modified Boyden chamber assay, we analyzed the chemotactic properties of MIP-1α on MM1.S, pat MM, H929, INA-6, and OPM2 cells. MIP-1α–specific migration could be observed in a dose-dependent fashion in MM1.S (1.7-fold), pat MM (21-fold), H929 (3.6-fold), INA-6 (1.4-fold), and OPM2 (2.1-fold) compared with control as shown in Figure 3A-E.

Furthermore, we wanted to investigate whether MIP-1α is able to induce migration of nonmyeloma cell lines like Nalm 6, Raji, BJAB (B-cell lines), and Jurkat (T-cell line). Migration experiments revealed that MIP-1α–dependent migration was not induced in any of these cell lines even at the highest concentration of 500 ng/mL (data not shown).

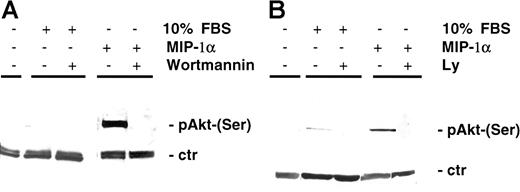

MIP-1α induces AKT phosphorylation

Previously it has been shown that, besides Raf/MEK/MAPK and JAK/STAT3 (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) pathways, which mediate survival and proliferation, AKT-dependent signaling is a major pathway in protection against apoptosis. In our study MIP-1α induced AKT phosphorylation (Ser473) in MM cells MM1.S (Figure 4A) as well as in pat MM (Figure 4B). AKT phosphorylation was inhibited by pretreatment of MM1.S cells with the PI3-K inhibitor LY 294002 (50 μM, 15 minutes) or wortmannin (1 μM, 15 minutes). Time course experiments showed that AKT was induced by MIP-1α starting 5 minutes after incubation and was still detectable up to 90 minutes following activation (data not shown).

MIP-1α induces migration of MM cells.

(A) MM1.S, (B) pat MM, (C) H929, (D) INA-6, and (E) OPM2 cell migration was measured using a modified Boyden chamber in the presence or absence of MIP-1α in media containing 0% FBS. MIP-1α (0.5, 5, 50, and 500 ng/mL) was added into the lower chamber, and cells migrated into the lower chamber were enumerated after 5 hours. Results were expressed in fold migration relative to control. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MIP-1α induces migration of MM cells.

(A) MM1.S, (B) pat MM, (C) H929, (D) INA-6, and (E) OPM2 cell migration was measured using a modified Boyden chamber in the presence or absence of MIP-1α in media containing 0% FBS. MIP-1α (0.5, 5, 50, and 500 ng/mL) was added into the lower chamber, and cells migrated into the lower chamber were enumerated after 5 hours. Results were expressed in fold migration relative to control. These results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

MIP-1α induces AKT phosphorylation in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were incubated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Pretreatment with PI3-K inhibitor wortmannin (1 μM) or LY 294002 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine addition. Pretreatment with either wortmannin or LY 294002 yielded similar results in MM1.S and pat MM cells (data not shown). Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-AKT (Ser473) antibody and AKT antibody as loading control (ctr).

MIP-1α induces AKT phosphorylation in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were incubated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Pretreatment with PI3-K inhibitor wortmannin (1 μM) or LY 294002 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine addition. Pretreatment with either wortmannin or LY 294002 yielded similar results in MM1.S and pat MM cells (data not shown). Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-AKT (Ser473) antibody and AKT antibody as loading control (ctr).

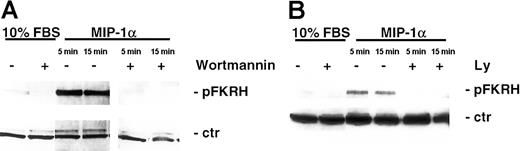

MIP-1α stimulates AKT and its downstream targets via PI3-K activation

To further support our findings that MIP-1α induced AKT activation, we next examined whether MIP-1α also induced phosphorylation of known downstream kinases in the AKT signaling cascade. As can be seen in Figure 5A-B, MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) led to phosphorylation of the transcription factor FKHR (Ser256). This activation by MIP-1α occurred as early as 5 minutes and was still detected after 90 minutes (data not shown). Importantly, this induction of phosphorylation was abrogated by pretreatment of MM1.S cells with the PI3-K–specific inhibitors LY 294002 (50 μM, 15 minutes) or wortmannin (1 μM, 15 minutes). In contrast, the forkhead family member AFX was constitutively expressed in cells and was unaffected by MIP-1α stimulation, and served as control for equal protein loading (Figure 5A-B).

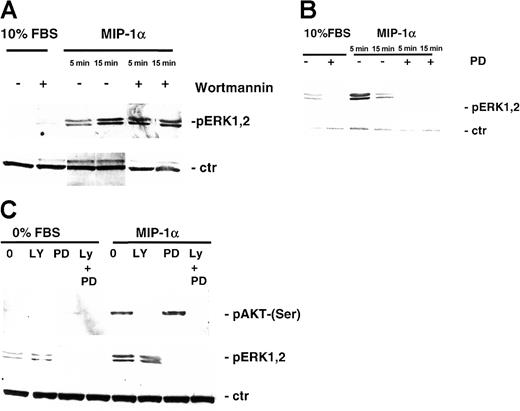

Activation of MAPK pathway by MIP-1α

We further studied the effect of MIP-1α on MEK/MAPK and STAT signaling pathway in MM1.S and pat MM cells by Western blotting with antiphospho-STAT3 and antiphospho-44/42 MAPK antibody with or without PI3-K and MEK1 inhibitor pretreatment. STAT3 was not activated by the treatment with MIP-1α (data not shown), whereas MIP-1α triggered p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation in MM1.S (Figure6A) and pat MM (Figure 6B) cells and could be inhibited by MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM, 15 minutes) (Figure 6B-C).

MIP-1α phosphorylates FKHR, downstream target of AKT/PKB pathway in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were incubated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 5 and 15 minutes. Pretreatment with PI3-K inhibitor wortmannin (1 μM) or LY 294002 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine treatment. Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-FKHR (Ser256) antibody. This mab is cross-reactive with AFX, which is constitutively expressed in MM1.S and pat MM cells and served as a loading control (ctr).

MIP-1α phosphorylates FKHR, downstream target of AKT/PKB pathway in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were incubated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 5 and 15 minutes. Pretreatment with PI3-K inhibitor wortmannin (1 μM) or LY 294002 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine treatment. Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-FKHR (Ser256) antibody. This mab is cross-reactive with AFX, which is constitutively expressed in MM1.S and pat MM cells and served as a loading control (ctr).

Effect of MIP-1α on MEK/MAPK signaling pathways in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were stimulated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 5 and 15 minutes. Pretreatment with 1 μM PI3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin or MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine treatment. Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-ERK1,2 ab. β-Actin antibody served as loading control. (C) MM1.S cells were pretreated with MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM, 1 hour) and/or PI3-K inhibitor LY 294002 (50 μM, 1 hour), stimulated with MIP-K (100 ng/mL, 15 minutes), and subjected to Western blotting using antiphospho-AKT (Ser473) (upper blot) or antiphospho-ERK1,2 antibody (middle panel). β-Actin antibody served as loading control (ctr; lower blot).

Effect of MIP-1α on MEK/MAPK signaling pathways in MM cells.

(A) MM1.S cells and (B) pat MM cells were stimulated with MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) for 5 and 15 minutes. Pretreatment with 1 μM PI3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin or MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM) was performed for 1 hour prior to cytokine treatment. Cells were lysed, electrophoresed, and immunoblotted with antiphospho-ERK1,2 ab. β-Actin antibody served as loading control. (C) MM1.S cells were pretreated with MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (50 μM, 1 hour) and/or PI3-K inhibitor LY 294002 (50 μM, 1 hour), stimulated with MIP-K (100 ng/mL, 15 minutes), and subjected to Western blotting using antiphospho-AKT (Ser473) (upper blot) or antiphospho-ERK1,2 antibody (middle panel). β-Actin antibody served as loading control (ctr; lower blot).

Reports showed that the MAPK pathway might be activated by a PI3-K–stimulated cascade in some cell types16 17; therefore it is conceivable that inhibiting PI3-K activity might prevent cytokine-dependent ERK activation. Thus, we investigated the ability of PI3-K inhibitors to inhibit MIP-1α–dependent ERK phosphorylation and conversely the ability of MEK1 inhibitor to block MIP-1α–induced AKT phosphorylation. MIP-1α (100 ng/mL) triggered p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation, and MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 inhibited phosphorylation. However, treatment with PI3-K inhibitor LY 249002 had no effect on MAPK activation (Figure 6C). Whereas MIP-1α–induced phosphorylation of AKT in MM1.S cells could be inhibited by PI3-K inhibitors (LY 249002 or wortmannin), no effect could be achieved by pretreatment with the MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (Figure 6C).

Discussion

Despite significant progress in understanding the biology of MM and promising advances in the development of treatment strategies, MM remains an incurable disease leading ultimately to death of all patients. Especially, osteolytic bone lesions are still a therapeutic challenge despite the use of bisphosphonates. Recently, Han et al18 clearly demonstrated that MIP-1α is an osteoclastic factor that appears to act directly on human OCL progenitors and also acts at the later stages of OCL differentiation. Antisense-mediated inhibition of MIP-1α was shown to block bone destruction in a SCID myeloma model. In addition to these effects our data show that MIP-1α also has direct effects on MM cells. Our studies suggest that MIP-1α might be an important component in the pathophysiology of MM by stimulating both MM cells and OCLs responsible for the development of lytic bone lesions.

MIP-1α is a member of the CC chemokines and interacts with 3 types of chemokines receptors (CCR1, CCR5, and CCR9).19 In this study we demonstrated that MIP-1α is secreted by several MM cell lines and patient-derived pat MM cells in very high concentrations up to 262 ng/mL. In accordance to our data is the finding that MIP-1α levels are elevated in the bone marrow plasma of 62% of patients with active myeloma.4 Furthermore, expression of MIP-1α receptor CCR5 was observed in MM cells. Despite the constitutively high secretion of MIP-1α in MM cells shown by our own data and others,20 we found that addition of exogenous MIP-1α at a concentration of up to 500 ng/mL increased proliferation of MM cells up to 4.7-fold and triggered migration up to 21-fold. In our experimental setting, proliferation assays were performed after the cells were washed with PBS twice to remove constitutively secreted cytokines and cultured thereafter in RPMI media containing low levels of FBS (2.5%). Therefore, the initial concentration of MIP-1α in proliferation assays of the starved and washed cells is very low, whereas measurement of MIP-1α secretion of MM cells was performed at the end of 48 hours of assay that could explain why MM cells show a response to exogenous MIP-1α. However, it is conceivable that MIP-1α might act indirectly by inducing the expression of a so far unknown factor. Thus, we wanted to investigate whether MIP-1α triggers secretion of IL-6 or other cytokines in MM cells. Therefore, MM1.S cells were treated with 100 ng/mL MIP-1α, and supernatants were collected after 48 hours. Analysis revealed that MIP-1α does not increase the secretion of IL-6 and 16 other cytokines (see “Material and methods”). In addition to that experiment we could show that MIP-1α does not induce STAT3 phosphorylation, whereas we and others have shown that IL-6 leads to STAT321 phosphorylation. Therefore, if MIP-1α acted by IL-6, we would expect to observe phosphorylation of STAT3.

Chauhan et al22,23 described that Dex is able to induce apoptosis in MM1.S cells, and IL-6 is able to prevent Dex-induced apoptosis by inhibition of activation of related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase (RAFTK).22 23 We therefore tested whether MIP-1α is able to block Dex-induced effects in MM1.S cells. In our experiments MIP-1α was not able to overcome Dex-induced growth inhibition, suggesting that the biologic effects of MIP-1α and IL-6 are mediated via different signaling cascades.

Because our data demonstrate that MIP-1α exerts its chemotactic properties on MM cells and that MIP-1α is also secreted by MM cells, these data could allow the hypothesis that homing of MM cells to the bone marrow and MM cluster cell formation in the bone marrow are at least partially mediated by MIP-1α.

Having demonstrated these distinct biologic effects of MIP-1α on MM cells, we began to delineate signaling pathways involved in these processes. To characterize downstream signaling molecules, we first investigated whether MIP-1α activated the MAPK pathway mediating DNA synthesis in MM cells. In time-course experiments, specific phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2 was observed. Phosphorylation was inhibited by pretreatment with MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059, also implicating MEK1 in the MIP-1α signaling cascade of MM cells. To support the importance of the MAPK pathway in mediating MIP-1α–triggered proliferation in MM cells, [3H]thymidine incorporation assays were carried out in MM1.S and pat MM cells in the absence and presence of PD 98059 and showed that MIP-1α–induced proliferation was blocked by PD 98059. Recently, an additional signaling cascade, the PI3-K/AKT pathway, has been described in MM cell, promoting the antiapoptotic survival effect of different cytokines.24,25 We therefore examined whether MIP-1α also induced phosphorylation of AKT/PKB signaling pathway and its downstream targets. MIP-1α induced phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) and the forkhead family member FKHR (Ser256). Notably, this induction of phosphorylation was inhibited by pretreatment with the PI3-K inhibitor LY 294002 (50 μM, 15 minutes) or wortmannin (1 μM, 15 minutes). Because a previous study had shown that IL-6–induced ERK activation and cell proliferation was inhibited by a PI3-K inhibitor, suggesting a cross talk between MAPK and PI3-K pathway,24 we tested whether PI3-K inhibitors were able to inhibit MIP-1α–induced ERK activation. Our results, however, clearly demonstrate in accordance with data from Tu at al25 that PI3-K inhibitors have no effect on ERK, but lead to a complete abrogation of the AKT phosphorylation and its downstream targets. In accordance with these findings, MEK1 inhibitor, which completely abrogates ERK activation, had no effect on AKT phosphorylation, suggesting that in our cell lines MIP-1α–induced activation of ERK and AKT pathways occur separately from each other without any cross talk.

Taken together, these data provide evidence that, in addition to being a stimulating factor for OCL and contributing to the development of lytic bone lesions, MIP-1α also has potent direct stimulating effects on MM cells leading to a dose-dependent increase of proliferation and MIP-1α–directed chemotaxis and, therefore, might contribute to the homing processes of MM cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. Furthermore, MIP-1α–induced signaling involved activation of the MAPK and AKT/PKB signaling pathway in MM cells leading to increased proliferation and survival.

In summary MIP-1α appears to have a major contribution to the pathobiology of MM leading to proliferation, survival, migration of MM cells, and bone destruction. Further studies are currently ongoing to delineate the precise mechanisms underlying the MIP-α–dependent direct effects and to address the issue whether blocking of MIP-1α could be a useful treatment strategy to decrease tumor burden, suppress homing of MM cells, and reduce bone destruction.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 27, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2383.

Supported in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (D.F.G.) KFO 105/1 and Charité research fund (85473209).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Suzanne Lentzsch, University Medical Center Charite, Campus Buch, Robert-Rössle-Klinik, 13125 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: lentzsch@rrk.charite-buch.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal