Major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) expression is regulated by the transcriptional coactivator CIITA. Positive selection of CD4+ T cells is abrogated in mice lacking one of the promoters (pIV) of the Mhc2ta gene. This is entirely due to the absence of MHCII expression in thymic epithelia, as demonstrated by bone marrow transfer experiments between wild-type and pIV−/− mice. Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) are also MHCII− in pIV−/− mice. Bone marrow–derived, professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) retain normal MHCII expression in pIV−/− mice, including those believed to mediate negative selection in the thymic medulla. Endogenous retroviruses thus retain their ability to sustain negative selection of the residual CD4+ thymocytes in pIV−/− mice. Interestingly, the passive acquisition of MHCII molecules by thymocytes is abrogated in pIV−/−mice. This identifies thymic epithelial cells as the source of this passive transfer. In peripheral lymphoid organs, the CD4+T-cell population of pIV−/− mice is quantitatively and qualitatively comparable to that of MHCII-deficient mice. It comprises a high proportion of CD1-restricted natural killer T cells, which results in a bias of the Vβ repertoire of the residual CD4+ T-cell population. We have also addressed the identity of the signal that sustains pIV expression in cortical epithelia. We found that the Jak/STAT pathways activated by the common γ chain (CD132) or common β chain (CDw131) cytokine receptors are not required for MHCII expression in thymic cortical epithelia.

Introduction

Major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) molecules are crucial for the development, survival, and activation of CD4+ T cells. Recognition of self-peptide–MHCII complexes on cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) determines whether or not immature CD4+ thymocytes are positively selected.1 Negative selection, mediated by MHCII+ thymic dendritic cells (DCs),2 results in the deletion of autoreactive CD4+ T cells. In the periphery, peptide-MHCII complexes expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) induce the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of CD4+ T helper cells. The central importance of these functions is illustrated by the phenotype of MHCII-deficient mouse strains,3-5 by the clinical course of patients suffering from bare lymphocyte syndrome (BLS),6-10 and by CIITA and RFX5-deficient mice, 2 murine models of BLS.11-14 Patients with BLS suffer from a severe primary immunodeficiency that is entirely attributable to the nearly complete absence of MHCII expression.6-10 Patients with BLS, as well as mice deficient for MHCII, CIITA, and RFX5, exhibit impaired maturation of CD4+ T cells and are unable to mount efficient CD4+ T helper cell–dependent immune responses.

CIITA is one of the 4 genes affected in BLS.6,7 It now is widely recognized to be the master regulator of MHCII expression. In most instances, it is the expression of CIITA that dictates the tightly controlled pattern of MHCII expression. Only MHCII+ APCs (B cells, DCs, macrophages) express CIITA constitutively. The expression of CIITA, and thus of MHCII genes, can be activated in MHCII− cells by stimulation with interferon γ (IFNγ).15-23 A large and complex regulatory region containing several independent promoters controls transcription of theMhc2ta gene. Of the 4 promoters identified in the human gene, 3 (pI, pIII, and pIV) are strongly conserved in the mouse. Promoter I is highly specific for DCs. Promoter III is used primarily in B cells but is also active in certain human DC preparations.19,24 25 Promoter IV is largely responsible for IFNγ-induced expression.

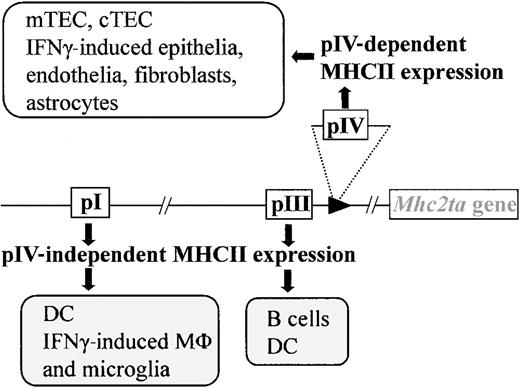

We have recently generated mice carrying a targeted deletion of promoter IV (pIV) (Figure 1). pIV−/− mice were engineered to carry a deletion of approximately 500 base pair (bp), encompassing exon IV and its associated promoter. Transcription from the remaining promoters (pI and pIII) is unaffected by the deletion of pIV.25 This ensures normal levels of basal and activated MHCII expression on B cells, macrophages, and DCs in the thymus and periphery of pIV−/− mice (Figure 1). IFNγ-induced MHCII expression on extrahematopoietic cells is on the other hand completely abrogated in pIV−/− mice.

Selective loss of MHCII expression in pIV−/− mice.

Mice with a targeted deletion of CIITA pIV lack IFNγ-induced MHCII expression on nonhematopoietic cells and constitutive MHCII expression on cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) and mTECs. Professional APCs retain IFNγ-induced CIITA expression via pI (microglia, macrophages) and constitutive expression via pI (DCs) and pIII (B cells, DCs).

Selective loss of MHCII expression in pIV−/− mice.

Mice with a targeted deletion of CIITA pIV lack IFNγ-induced MHCII expression on nonhematopoietic cells and constitutive MHCII expression on cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) and mTECs. Professional APCs retain IFNγ-induced CIITA expression via pI (microglia, macrophages) and constitutive expression via pI (DCs) and pIII (B cells, DCs).

Surprisingly, pIV−/− mice also lack MHCII expression in the thymic cortex.25 This results in a defect in cTEC-mediated positive selection and in drastically reduced numbers of CD4+ T cells in the thymus and periphery. The periphery of pIV−/− mice contains ample numbers of MHCII+ DCs, B cells, and macrophages. Interactions between the T-cell receptor (TCR) of CD4+ T cells and MHCII molecules on peripheral APCs are believed to be crucial for the survival of CD4+ T cells.26 27CD4+ T cells should thus encounter a favorable environment for their survival in pIV−/− mice. These mice therefore represent an unprecedented model in which to study the fate of the residual CD4+ T cells generated in the absence of the “classical” positive selection pathway.

In this study we characterized the residual population of CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice. We further defined MHCII expression in the thymus of pIV−/− mice and analyzed negative selection by endogenous retroviruses. To address the question on the transcription factors required for constitutive MHCII expression on cTECs, we analyzed positive selection of CD4+T cells in mice lacking stromal expression of interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R) or the common gamma chain.

Materials and methods

Mice and generation of bone marrow chimeras

Mice carrying a deletion of pIV of the Mhc2ta gene were generated previously in our laboratory.25I-Aα−/− mice were a generous gift from H. Bluethmann5 (Hoffman La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). IL-7R–deficient mice were previously described.28 To introduce a functional I-E allele in the original Sv129-C57Bl/6 background, pIV−/− mice were backcrossed to B10BR animals. F2 offspring were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to distinguish between the wild-type (primers F1 + r1) and deleted (primers F2 + r2) alleles of pIV: F1, 5′-CCTAGGAGCCACGGAGCTG-3′; r1, 5′-TCCAGAGTCAGAGGTGGTC-3′; f 2, 5′-CAGACTATCCTGAAA-TGCC-3′; r2, 5′-CGAGATCTAGATATCGATAAGCTTG-3′. pIV−/− F2 progeny were tested for I-E expression by fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanner (FACS). All other experiments were performed with CIITA pIV−/− and pIV+/− littermates on a mixed Sv129-C57Bl/6 background. Mice 8 to 12 weeks of age were used to generate bone marrow chimeras. A total of 107 cells depleted of mature CD4+cells (by negative selection using monoclonal anti-CD4 antibodies and magnetic beads [Dynal, Oslo, Norway] according to the manufacturer's instructions) were transferred per recipient (irradiated with 3 Gy). Mixed bone marrow chimeras were reconstituted with an equal number of bone marrow cells derived from CD45.2 pIV−/− mice and CD45.1 congenic C57BL/6 mice.29 All bone marrow transfer experiments involving pIV−/− mice (Table 1; Figures 3 and6) were performed using the congenic markers Ly5.1 and Ly5.2. Reconstitution of the chimeras was allowed for 2 months. The analysis of reconstituted IL-7R–deficient mice did not require the use of congenic markers, because few endogenous CD4+ T cells are produced. The same applies to nude mice reconstituted with c-kit, gamma-c–deficient thymuses (Figure8). c-Kit, γc–deficient thymuses30 were transplanted under the kidney capsule of nude mice. The thymocytes were analyzed 8 weeks later for CD4 and CD8 expression. Animals were housed either under specific pathogen-free conditions at Research and Consulting Company (RCC), Fullinsdorf, Switzerland, or under standard conditions in a conventional mouse facility.

Characterization of bone marrow chimeras

| Group; no. of mice (graft→host) . | % Total thymocytes (% Ly5. within the subset) . | % Total splenocytes (% Ly5. within the subset) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+CD8+ . | CD8+ . | CD4+ . | CD3−CD4− . | CD3+CD4− . | CD4+ . | |

| A; n = 2 | 79, 69 | 3.3, 2.8 | 17, 11 | 61, 60 | 11, 7 | 25, 25 |

| (5.2 wt→5.1 wt) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (21, 12) | (10, 18) |

| B; n = 4 | 81 ± 3 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 11 ± 2 | 67 ± 3 | 6 ± 0.7 | 21 ± 1 |

| (5.2 pIV−/−→5.1 wt) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (< 2) | (17 ± 2) | (12 ± 3) |

| C; n = 4 | 92 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 83 ± 5 | 10 ± 3 | 2 ± 0.4 |

| (5.1 wt→5.2 pIV−/−) | (>98) | (>98) | (>98) | (>98) | (78 ± 6) | (65 ± 3) |

| D; n = 3 | 77 ± 2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 0.3 | 65 ± 3 | 9 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 0.3 |

| (mix→5.1 wt) | (81 ± 4) | (77 ± 2) | (78 ± 2) | (43 ± 9) | (74 ± 10) | (72 ± 10) |

| E; n = 2 | 89, 88.2 | 2.9, 1.9 | 0.9, 0.6 | 83, 77 | 11.1, 10.5 | 2.5, 1.8 |

| (mix→5.2 pIV−/−) | (85, 87) | (84, 82) | (82, 81) | (53, 40) | (64, 55) | (53, 51) |

| F; n = 1 | 92 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 84 | 10 | 2.4 |

| (5.2 pIV−/−→5.2 pIV−/−) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) |

| Group; no. of mice (graft→host) . | % Total thymocytes (% Ly5. within the subset) . | % Total splenocytes (% Ly5. within the subset) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+CD8+ . | CD8+ . | CD4+ . | CD3−CD4− . | CD3+CD4− . | CD4+ . | |

| A; n = 2 | 79, 69 | 3.3, 2.8 | 17, 11 | 61, 60 | 11, 7 | 25, 25 |

| (5.2 wt→5.1 wt) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (21, 12) | (10, 18) |

| B; n = 4 | 81 ± 3 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 11 ± 2 | 67 ± 3 | 6 ± 0.7 | 21 ± 1 |

| (5.2 pIV−/−→5.1 wt) | (<2) | (<2) | (<2) | (< 2) | (17 ± 2) | (12 ± 3) |

| C; n = 4 | 92 ± 2 | 2 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 83 ± 5 | 10 ± 3 | 2 ± 0.4 |

| (5.1 wt→5.2 pIV−/−) | (>98) | (>98) | (>98) | (>98) | (78 ± 6) | (65 ± 3) |

| D; n = 3 | 77 ± 2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 0.3 | 65 ± 3 | 9 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 0.3 |

| (mix→5.1 wt) | (81 ± 4) | (77 ± 2) | (78 ± 2) | (43 ± 9) | (74 ± 10) | (72 ± 10) |

| E; n = 2 | 89, 88.2 | 2.9, 1.9 | 0.9, 0.6 | 83, 77 | 11.1, 10.5 | 2.5, 1.8 |

| (mix→5.2 pIV−/−) | (85, 87) | (84, 82) | (82, 81) | (53, 40) | (64, 55) | (53, 51) |

| F; n = 1 | 92 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 84 | 10 | 2.4 |

| (5.2 pIV−/−→5.2 pIV−/−) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) |

FACS analysis of bone marrow chimeras obtained by grafting Ly 5.1 or Ly 5.2 wild-type (wt) donor cells or Ly 5.2 pIV−/− donor cells into hosts of the indicated phenotype.

Cytofluorimetric analysis

Single-cell suspensions from peripheral lymph nodes, thymus, or spleen were prepared by crushing the tissues between 2 frosted glass slides. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were harvested by tail blood sampling and isolated by centrifugation on a Ficoll gradient. Ice-cooled single-cell suspensions were pretreated with Fc-block (anti-CD16/CD32; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and then incubated with specific antibodies (PharMingen) directed against CD4 (RM4–5), CD8 (53–6.7), I-Ab (AF6–120.1) I-Ed (14-4-4S), Ly5.1 (A20), Ly5.2 (104), NK-1.1 (PK136), CD62L (MEL-14), CD44H (TM-1), CD54 (3E2), TCRβ (H57-597), CD3 (17A2), Vβ3 (KJ25), Vβ4 (KT4), Vβ5.1 and 5.2 (MR9-4), Vβ6 (RR4-7), Vβ7 (TR310), Vβ8 (F23.1), Vβ9 (MR10-2), Vβ10b (B21.5), Vβ11 (RR3-15), Vβ12 (MR11-1), Vβ13 (MR12-3), Vβ14 (14-2). Then 104 (primary cultures) to 105 (suspensions from fresh organs) cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer)–loaded tetramers were a generous gift from M. Kronenberg, San Diego, CA. Detection of CD1-restricted natural killer T (NKT) cells with mCD1 tetramers loaded with α-GalCer were performed as described previously.31 Briefly, cells were pretreated with Fc-block (anti-CD16/CD32; PharMingen) and neutravidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 4°C and then stained for 20 minutes at 23°C with anti-NK1.1 Ab, anti-CD4 Ab, anti-TCRβ Ab and α-GalCer–loaded mCD1 (tetramerized with neutravidin phycoerythrin).

Immunohistochemistry

Sections (8-μm) from frozen adult organs and whole newborn mice were air dried, fixed in ice-cold acetone, blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.6% H2O2, 5% goat serum and 0.1% NaN3, and stained with digoxygenin-conjugated antibody directed against MHCII (M5/114), F4/80 (Serotec no. MCAP497), CD11c (HL3; Pharmingen), and keratin (antipankeratin serum provided by E. Reichmann, Zurich, Switzerland). Staining was revealed using antidigoxygenin peroxidase and 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Sigma-Aldrich) to give a red precipitate. Sections were counterstained with methylene blue.

Immunofluorescence

For detection of MHCII expression by medullary epithelial cells, thymuses were isolated and embedded in cryoembedding media (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek Europe BV, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands). Frozen samples were cut into sections 6 mm thick, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, and exposed to PBS with 1% fetal calf serum 0.1% Tween at pH 7.3 for 10 minutes before incubation with primary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Washing was repeated before incubation with the secondary antibody (20 minutes at room temperature). Isotype controls were used in all experiments. Thymic sections were stained for MTS10 (Pharmingen) and costained against I-Aβ (AF6-120.1; Pharmingen).32 Medullary areas were microscopically localized and analyzed by 2-color immunofluorescence with a confocal microscope (Carl-Zeiss AG, Feldbach, Switzerland).

Results

Positive selection of CD4+ T cells is abrogated in pIV−/− mice

To our surprise, a severe depletion of CD4+ T cells was observed when we examined thymocytes and mature peripheral T cells in pIV−/− mice.25 The single-positive CD4+ T-cell numbers and percentages in pIV−/−thymuses did not exceed those found in MHCII-deficient mice (Figure2A). In contrast, CD8+ and double-positive CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes are present in normal or slightly increased numbers. In the peripheral lymphoid organs, the percentage of CD4+ T cells is reduced to 1%-5% of total lymphocyte numbers (Figure 2B-C), while that of CD8+ T cells is markedly increased. The extent of the CD4+ T-cell deficiency in pIV−/− mice was surprising because MHCII expression is normal on B cells, macrophages, and DCs in all organs, including the thymus.25 Since peripheral MHC/peptide engagements have been shown to be necessary for the survival and homeostatic expansion of CD4+ T cells,26 27 the peripheral MHCII+ environment of pIV−/− mice should permit the survival and accumulation of any positively selected CD4+ T cells. In spite of this, CD4+ T-cell counts are as low as in mice that have a complete lack of MHCII expression, such as CIITA, RFX5, and MHCII-deficient mutants.

The depletion of CD4+ T cells found in pIV−/− mice is comparable to that observed in Aα−/− mice.

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations were analyzed by FACS. Numbers indicate the percentage of CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ cells. (A) Representative FACS analysis of thymocytes from pIV+/−, pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice. (B) % of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations from the lymph nodes, spleen, and PBLs were analyzed for pIV−/− mice and pIV+/− control littermates. (C) Representative FACS analysis showing the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations in lymph nodes from control pIV+/−, pIV−/−, and I-Aα−/−mice.

The depletion of CD4+ T cells found in pIV−/− mice is comparable to that observed in Aα−/− mice.

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations were analyzed by FACS. Numbers indicate the percentage of CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ cells. (A) Representative FACS analysis of thymocytes from pIV+/−, pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice. (B) % of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations from the lymph nodes, spleen, and PBLs were analyzed for pIV−/− mice and pIV+/− control littermates. (C) Representative FACS analysis showing the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations in lymph nodes from control pIV+/−, pIV−/−, and I-Aα−/−mice.

There are 2 explanations that could account for the loss of CD4+ T cells. First, pIV could be essential for MHCII expression in the thymic compartment that drives positive selection of CD4+ T cells. The lack of MCHII expression in pIV−/− thymuses would have to be very tight because MHCII+ DCs, B cells, and macrophages in the periphery of pIV−/− mice should ensure the survival of any positively selected CD4+ T cells. The second possibility is that pIV performs a function that is intrinsically important for T-cell development. For instance, CIITA has been suggested to be involved in the differentiation of peripheral CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells.33 To discriminate between these possibilities we produced radiation bone marrow chimeras with various combinations of recipient and donor phenotypes (Table 1). The development of T cells was examined 2 months after engraftment. The origin of the lymphocytes was assessed by using the congenic markers Ly 5.1 and Ly 5.2.29 Most CD3-negative lymphocytes were of donor origin. In all chimeras, a small fraction of recipient cells persisted in the CD3-positive subset.

When both the recipient and donor phenotypes are wild type, all lymphocyte populations are reconstituted to normal levels (Table 1, group A). This is also true when wild-type mice are reconstituted with pIV−/− donor cells (Table 1, group B). In contrast, pIV−/− mice reconstituted with either wild-type (Table 1, group C) or pIV−/− donor cells (Table 1, group F) had very low CD4+ T-cell counts but normal levels of CD8+ T cells. We also mixed wild-type with pIV−/− donor cells and reconstituted wild-type or pIV−/− mice (Table 1, groups D and E). Again, CD4+ T cells were generated normally if the recipient was wild type (Table 1, group D), whereas pIV−/− recipients were unable to produce normal numbers of CD4+ T cells (Table 1, group E). Taken together these results exclude the possibility that the lack of CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice could be due to an intrinsic defect in bone marrow progenitors.

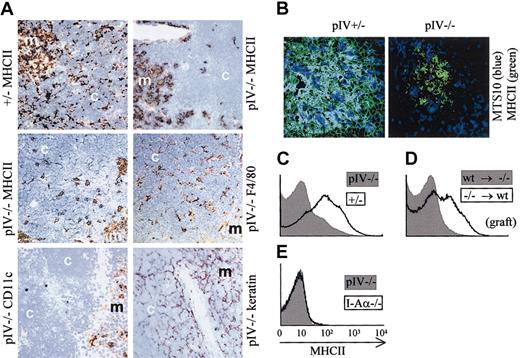

pIV−/− mice specifically lack MHCII expression on thymic epithelial cells

The thymus of pIV−/− mice is characterized by an abnormal pattern of MHCII expression (Figure3A). In wild-type thymuses, the cortex shows a fine reticular pattern of MHCII expression that is characteristic of the epithelial cell matrix. In the medulla, the staining is more diffuse and is attributable to DCs, B cells, macrophages, and medullary epithelial cells. In pIV−/−mice, the cortical reticular staining is absent, indicating that the cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) lack MHCII expression. Only patchy areas of MHCII expression remain in the cortex. In contrast, the diffuse staining of the medulla is similar to wild-type controls. By staining of adjacent sections, the patchy MHCII expression in the cortex was found to colocalize with F4/80 positive macrophages. CD11c-positive cells, on the other hand, were restricted to the medulla and corticomedullary junction, in accordance with previous studies.34 Finally, the fine reticular stain obtained with an antikeratin antibody is consistent with a conserved architecture of the thymic stroma. Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) were analyzed by immunofluorescence for MHCII expression (Figure 3B). In control pIV+/− thymic medulla, the majority of MTS10+ cells (major mTECs) express MHCII. Strikingly, in pIV−/−mice MTS10+ mTECs do not express MHCII. The absence of MHCII expression by mTECs has been confirmed by FACS experiments (data not shown).

pIV−/− mice lack MHCII expression on thymic epithelial cells, and passive transfer of MHCII molecules to T cells is abrogated.

(A) Thymic sections were stained (brown) for MHCII, F4/80, CD11c, and epithelial cells (keratin). The counterstain is methylene blue. The strong reduction in MHCII expression in pIV−/− thymuses is restricted to the cortex (compare upper 2 panels). In pIV−/− thymuses, the residual patchy MHCII expression in the cortex overlaps with F4/80+ thymic macrophages (compare middle 2 panels). CD11c-positive DCs are restricted to the medulla (bottom left panel). The keratin stain indicates a normal architecture of the stroma in both the cortex and the medulla (bottom right panel). m indicates medulla; c, cortex. Original magnification, × 200 for all images in panels A and B. (B) Immunohistology of thymic medullary areas. MTS10+ and MHCII+ medullary cells appear blue and green, respectively. Double-positive cells appear cyan in the thymic medulla from the pIV+/− control. No costaining is observed in the pIV−/− medulla. (C-E) Passive transfer of MHCII molecules to thymocytes does not occur in pIV−/− mice. (C) MHCII expression was analyzed by FACS on double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes from pIV−/−(gray profile) and pIV+/− mice (open profile). (D) Double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes derived from pIV−/− bone marrow progenitors acquire MHCII molecules by passive transfer if they develop in the thymus of an irradiated wild-type recipient (open profile). On the other hand, wild-type thymocytes developing in a pIV−/− recipient do not acquire MHCII molecules (gray profile). pIV−/− donor cells (open profile) were identified by gating on Ly5.2+ cells. Wild-type donor cells (gray profile) were selected within the Ly5.1+ gate. (E) MHCII expression on double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes is compared between pIV−/− mice (gray profile) and I-Aα−/−mice (open profile).

pIV−/− mice lack MHCII expression on thymic epithelial cells, and passive transfer of MHCII molecules to T cells is abrogated.

(A) Thymic sections were stained (brown) for MHCII, F4/80, CD11c, and epithelial cells (keratin). The counterstain is methylene blue. The strong reduction in MHCII expression in pIV−/− thymuses is restricted to the cortex (compare upper 2 panels). In pIV−/− thymuses, the residual patchy MHCII expression in the cortex overlaps with F4/80+ thymic macrophages (compare middle 2 panels). CD11c-positive DCs are restricted to the medulla (bottom left panel). The keratin stain indicates a normal architecture of the stroma in both the cortex and the medulla (bottom right panel). m indicates medulla; c, cortex. Original magnification, × 200 for all images in panels A and B. (B) Immunohistology of thymic medullary areas. MTS10+ and MHCII+ medullary cells appear blue and green, respectively. Double-positive cells appear cyan in the thymic medulla from the pIV+/− control. No costaining is observed in the pIV−/− medulla. (C-E) Passive transfer of MHCII molecules to thymocytes does not occur in pIV−/− mice. (C) MHCII expression was analyzed by FACS on double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes from pIV−/−(gray profile) and pIV+/− mice (open profile). (D) Double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes derived from pIV−/− bone marrow progenitors acquire MHCII molecules by passive transfer if they develop in the thymus of an irradiated wild-type recipient (open profile). On the other hand, wild-type thymocytes developing in a pIV−/− recipient do not acquire MHCII molecules (gray profile). pIV−/− donor cells (open profile) were identified by gating on Ly5.2+ cells. Wild-type donor cells (gray profile) were selected within the Ly5.1+ gate. (E) MHCII expression on double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes is compared between pIV−/− mice (gray profile) and I-Aα−/−mice (open profile).

Thymocytes acquire MHCII molecules by passive transfer from TECs

Mouse T cells do not express significant amounts of CIITA and are consequently devoid of MHCII molecules. However, experiments with radiation chimeras35 have indicated that mouse thymocytes can acquire MHCII molecules in a cell contact–dependent fashion. Thymocytes acquire these MHCII molecules by passive transfer from an unidentified thymic stromal cell.36 Strikingly, the passive transfer of MHCII to CD4+CD8+thymocytes is abrogated in pIV−/− mice (Figure 3C). In irradiated recipients reconstituted with pIV−/− donor cells, the passive MHCII transfer to thymocytes was corrected only if the host thymus is wild type (Figure 3D and data not shown). In contrast, wild-type thymocytes grafted into irradiated pIV−/− hosts remain MHCII−. The lack of MHCII transfer in pIV−/− mice is complete, as shown by the negative control (I-Aα−/− mice) in Figure 3E. These observations confirm that the presence of MHCII molecules at the surface of thymocytes results from a passive transfer from cTECs or mTECs.

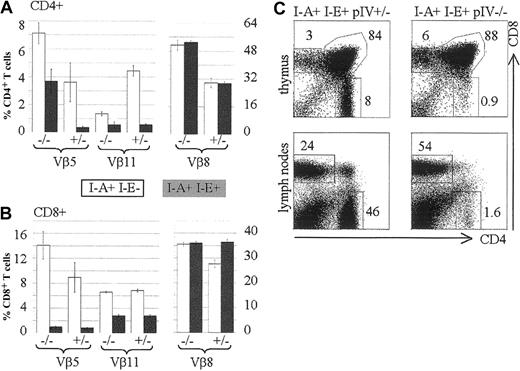

Negative selection by endogenous mtv superantigens is conserved in pIV−/−mice

The data obtained from radiation chimeras and the histologic findings in pIV−/− thymuses strongly argue that the CD4+ T-cell deficiency in pIV−/− mice is entirely attributable to the lack of MHCII expression by cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs). In contrast to other MHCII-deficient mutants, pIV−/− mice retain normal MHCII expression on B cells, DCs, and macrophages in both the thymus and the periphery.25 This provided a unique opportunity to test whether MHCII+ APCs can perform negative selection in the absence of positive selection of CD4+ T cells. With this aim, we examined clonal deletion of T cells in pIV−/−mice. T cells expressing Vβ5 and Vβ11 TCRs are deleted in the thymus of mouse strains that express I-E and retroviral superantigens encoded by mtv-8 and -9.37 Because pIV−/− mice were generated in a mixed B6/129 background (b haplotype), they lack a functional I-Eα gene. To obtain efficient, superantigen-mediated deletion we therefore introduced a functional I-E allele by crossing the pIV−/− mice with B10.BR mice. Figure 4A compares the frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing Vβ5, Vβ11, and Vβ8 in the presence and absence of the I-Eα gene. In wild-type mice and in pIV−/− mice, introduction of the I-Eα gene has no effect on the control Vβ8 family. In wild-type mice, introduction of the I-Eα gene leads to efficient deletion of the susceptible Vβ5 and Vβ11 families. A deletion of the Vβ11 family and, to a lesser extent, of the Vβ5 subset was also observed in the residual CD4+ T-cell population of pIV−/− mice. The fact that deletion in the CD4+ Vβ5 subset is only partial in pIV−/− mice may be explained by the recently described MHCI- and MHCII-independent population of CD4+ T cells.38 This population displays a 6-fold increase in Vβ5 expression, which becomes apparent in the residual CD4+ T-cell compartment of pIV−/− mice. In the CD8+ T-cell compartment, the I-E dependent, superantigen-mediated deletion of the Vβ5 and Vβ11 families was, as expected, similar in pIV−/− and control littermates (Figure 4B). There was again no change in the percentage of Vβ8+ CD4+ T cells after introduction of the I-Eα gene. Taken together, these results establish that superantigen-mediated negative selection of CD4+ T cells occurs normally in pIV−/− mice. The residual CD4+ thymocytes in pIV−/− mice are negatively selected despite the defect in their positive selection. This defect in positive selection is as strong in the B10BR background as it is in the mixed Sv129-C57Bl/6 background (compare Figure 4C to Figure 2).

Negative selection occurs normally in pIV−/− mice.

Vβ5, Vβ11, and Vβ8 subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed by FACS of splenocytes extracted from pIV−/− mice and control pIV+/−littermates. The numbers indicated alongside the bar graphs represent the percentages of the indicated Vβ family relative to the total CD4+ (A) or CD8+ (B) T-cell populations. White and filled bars represent the mean value (2 to 4 mice) for a nondeleting (I-E−) and a deleting (I-E+) background, respectively. (C) Representative FACS analysis showing the CD4 and CD8 populations in B10BR thymuses and lymph nodes. B10BR controls (I-E+ I-A+ pIV+/−, on the left) are compared with B10BR pIV−/− mice (I-E+ I-A+ pIV−/− , on the right).

Negative selection occurs normally in pIV−/− mice.

Vβ5, Vβ11, and Vβ8 subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed by FACS of splenocytes extracted from pIV−/− mice and control pIV+/−littermates. The numbers indicated alongside the bar graphs represent the percentages of the indicated Vβ family relative to the total CD4+ (A) or CD8+ (B) T-cell populations. White and filled bars represent the mean value (2 to 4 mice) for a nondeleting (I-E−) and a deleting (I-E+) background, respectively. (C) Representative FACS analysis showing the CD4 and CD8 populations in B10BR thymuses and lymph nodes. B10BR controls (I-E+ I-A+ pIV+/−, on the left) are compared with B10BR pIV−/− mice (I-E+ I-A+ pIV−/− , on the right).

Thymocytes and peripheral CD4+ T cells exhibit the same activated phenotype in pIV−/− and MHCII-deficient mice

CD4+ T cells in MHCII-deficient mice present typical anomalies in the expression of several cell surface markers. Figure5A shows that CD4+ thymocytes of pIV−/− mice present the same anomalies as their counterparts isolated from animals fully deficient in MHCII molecules. CD4+ thymocytes have reduced TCR levels in both I-Aα−/− and pIV−/− mice. MHCII deficiency also has been reported to have an impact upstream of the CD4+ single-positive stage, leading to elevated CD4 and TCR levels on double-positive CD4+CD8+thymocytes.39 This phenotype is again reproduced in the pIV−/− animals.

Thymocytes and CD4+ T cells from pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice display a similar phenotype.

(A) Double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes from pIV−/− mice express higher levels of TCR and CD4 than controls (top 2 histograms). CD8 levels are similar to controls (data not shown). Single-positive CD4+ T cells display lower TCR levels in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− thymuses compared to control littermates (middle 2 histograms). This is not observed for CD8+ T cells (bottom 2 histograms). (B) CD4+ splenocytes were analyzed by FACS for CD62L, CD54, and TCR expression. CD62L and TCR levels are lower in I-Aα−/− and pIV−/− CD4+ T cells than in controls. CD54 is increased in both mutants. (C) CD8+ T cells from the spleens of I-Aα−/− , pIV−/−, and control littermates are similar with respect to their expression levels of CD62L, CD54, and TCR.

Thymocytes and CD4+ T cells from pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice display a similar phenotype.

(A) Double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes from pIV−/− mice express higher levels of TCR and CD4 than controls (top 2 histograms). CD8 levels are similar to controls (data not shown). Single-positive CD4+ T cells display lower TCR levels in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− thymuses compared to control littermates (middle 2 histograms). This is not observed for CD8+ T cells (bottom 2 histograms). (B) CD4+ splenocytes were analyzed by FACS for CD62L, CD54, and TCR expression. CD62L and TCR levels are lower in I-Aα−/− and pIV−/− CD4+ T cells than in controls. CD54 is increased in both mutants. (C) CD8+ T cells from the spleens of I-Aα−/− , pIV−/−, and control littermates are similar with respect to their expression levels of CD62L, CD54, and TCR.

The similarity between pIV−/− and MHCII-deficient mice extends to the peripheral T-cell compartments. The residual CD4+ T cells in the periphery of pIV−/− mice have the same activated phenotype as the CD4+ T cells of MHCII-deficient mice (Figure 5B). They display a down-regulation of CD62L with a concomitant increase in CD54. Moreover, their TCR levels are markedly reduced. In contrast, CD8+ T cells do not present these anomalies in either the pIV−/−or MHCII-deficient mice (Figure 5C). We conclude that normal MHCII expression in the periphery of pIV−/− mice does not prevent the residual CD4+ T cells from adopting an activated phenotype.

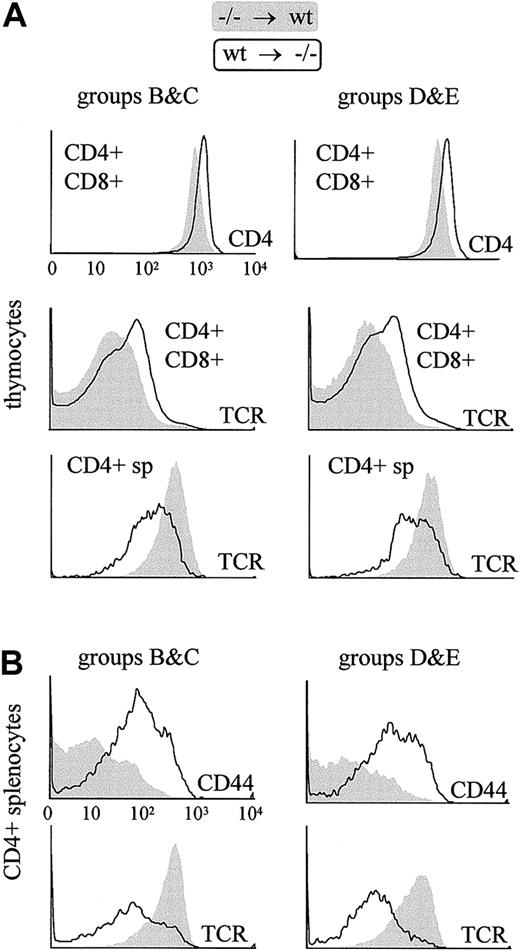

There are 2 explanations that could account for the unusual activated phenotype of the residual CD4+ T cells in the pIV−/− mice. First, the absence of pIV expression in the CD4+ T cells could itself induce an abnormal phenotype. Alternatively, the atypical phenotype could result not from an intrinsic defect in CD4+ T cells but from the development of these cells in the absence of MHCII expression on TEC. The analysis of CD4+ T cells in the radiation chimeras described above (Table 1) is consistent with the latter hypothesis. CD4+ T cells that developed in wild-type hosts display wild-type levels of cell-surface markers even if they are derived from pIV−/−donor cells. On the other hand, wild-type CD4+ T cells that developed in pIV−/− recipients exhibit the same characteristic alterations seen in the pIV−/− and MHCII-deficient mutants (Figure 6). These results rule out the possibility that pIV expression in bone marrow–derived cells is required to obtain a normal phenotype in CD4+ T cells.

The characteristic cell surface phenotype of thymocytes and peripheral CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice is reproduced in bone marrow chimera experiments only if the irradiated recipient is a pIV−/− mouse.

Filled profiles represent T cells derived from pIV−/−progenitors grafted into a wild-type host. Open profiles represent T cells derived from wild-type progenitors grafted into a pIV−/− host. T cells were identified as donor-derived by gating with the appropriate congenic marker (Ly5.1 or Ly5.2). Groups B, C, D, and E refer to the groups of bone marrow chimeras listed in Table1. The 6 histograms in the upper panel reveal that thymocytes derived from wild-type bone marrow progenitors present alterations identical to those described in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/−mice if they develop in a pIV−/− host. The 4 histograms in the lower panel represent a similar analysis of splenic CD4+ T cells. Peripheral pIV−/−CD4+ T cells display a normal surface phenotype when they develop in wild-type hosts, whereas wild-type CD4+ T cells that develop in pIV−/− recipients up-regulate CD44 and express lower levels of TCR.

The characteristic cell surface phenotype of thymocytes and peripheral CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice is reproduced in bone marrow chimera experiments only if the irradiated recipient is a pIV−/− mouse.

Filled profiles represent T cells derived from pIV−/−progenitors grafted into a wild-type host. Open profiles represent T cells derived from wild-type progenitors grafted into a pIV−/− host. T cells were identified as donor-derived by gating with the appropriate congenic marker (Ly5.1 or Ly5.2). Groups B, C, D, and E refer to the groups of bone marrow chimeras listed in Table1. The 6 histograms in the upper panel reveal that thymocytes derived from wild-type bone marrow progenitors present alterations identical to those described in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/−mice if they develop in a pIV−/− host. The 4 histograms in the lower panel represent a similar analysis of splenic CD4+ T cells. Peripheral pIV−/−CD4+ T cells display a normal surface phenotype when they develop in wild-type hosts, whereas wild-type CD4+ T cells that develop in pIV−/− recipients up-regulate CD44 and express lower levels of TCR.

Taken together, our results show that the activated phenotype of CD4+ T cells is a consequence of deficient MHCII expression on cTECs and mTECs. This is consistent with the finding that the residual CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− and MHCII−/− mice share the same atypical phenotype. Moreover, the fact that these 2 mutants exhibit the same phenotype implies that it must arise independently of whether or not peripheral APCs express MHCII molecules.

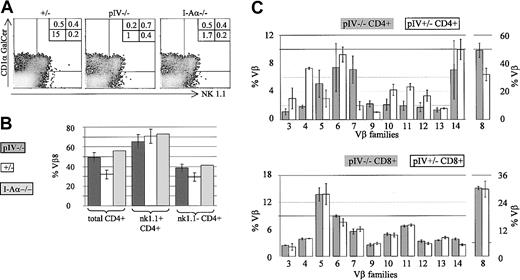

A large proportion of the residual CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice are CD1-restricted NKT cells

In addition to the activated phenotype, the residual CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice contain a higher proportion of Vβ8+ and Vβ7+ cells (see Figure 7). These features are typical of NKT cells.40,41 This led us to suspect that the residual CD4+ T-cell population in pIV−/− mice contains a high proportion of NKT cells. We therefore performed a 4-color FACS analysis with antibodies directed against CD4, TCR-β, and NK1.1, and with CD1 tetramers coupled to αGalCer (Figure 7A). The tetramers allowed us to detect NKT cells that stain negative for the NK1.1 marker.42 CD4+ T cells from pIV−/−, MHCII-deficient, and wild-type mice were found to comprise similar absolute numbers of NK1.1+ and CD1-restricted cells. In contrast, the NK1.1-CD1αGalCer− CD4+ T cells, which comprise the classical MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cells, are much less abundant in the MHCII-deficient and pIV−/−animals. The consequence is a considerably higher proportion of NKT cells in the pIV−/− and MHCII-deficient animals (up to half of the total number of CD4+ T cells).

The proportion of CD1-restricted and NK1.1+ cells is increased in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice.

(A) The density plots show NK1.1 and CD1αGalCer-tetramer staining of CD4+, TCRβ+ T cells from pIV+/−, pIV−/−, and I-Aα−/− mice. Numbers indicate the percentage of CD4+ T cells in each quadrant relative to the total number of cells. NK1.1−, tetramer−, CD4+ T cells (lower left quadrant) are reduced 10- to 15-fold in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice. In contrast, similar percentages of NK1.1+ and tetramer+ cells are detected in the control and mutant mice. (B) The higher proportion of NKT cells in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice leads to an increase in the numbers of Vβ8+ CD4+ T cells. The bar graph shows the mean percentages of Vβ8+ cells for the 3 mouse strains. Total CD4+ T cells comprise a higher proportion of Vβ8+ cells in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice as compared to control pIV+/−littermates (left). NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells exhibit a similar Vβ8 bias in all 3 mouse strains (right). (C) Representation of various Vβ families in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in pIV−/− mice and control pIV+/−littermates. The upper bar graph indicates the mean percentage of the CD4+ T cells belonging to the indicated Vβ families (at least 4 mice for each data point). The higher proportion of NKT cells in the pIV−/− mice leads to an increase in the percentage of Vβ8 and Vβ7 CD4+ T cells. As a result, the representation of most other families is reduced. The distribution of Vβ families in CD8+ T cells is identical between control and pIV−/− mice (lower bar graph).

The proportion of CD1-restricted and NK1.1+ cells is increased in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice.

(A) The density plots show NK1.1 and CD1αGalCer-tetramer staining of CD4+, TCRβ+ T cells from pIV+/−, pIV−/−, and I-Aα−/− mice. Numbers indicate the percentage of CD4+ T cells in each quadrant relative to the total number of cells. NK1.1−, tetramer−, CD4+ T cells (lower left quadrant) are reduced 10- to 15-fold in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice. In contrast, similar percentages of NK1.1+ and tetramer+ cells are detected in the control and mutant mice. (B) The higher proportion of NKT cells in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice leads to an increase in the numbers of Vβ8+ CD4+ T cells. The bar graph shows the mean percentages of Vβ8+ cells for the 3 mouse strains. Total CD4+ T cells comprise a higher proportion of Vβ8+ cells in pIV−/− and I-Aα−/− mice as compared to control pIV+/−littermates (left). NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells exhibit a similar Vβ8 bias in all 3 mouse strains (right). (C) Representation of various Vβ families in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in pIV−/− mice and control pIV+/−littermates. The upper bar graph indicates the mean percentage of the CD4+ T cells belonging to the indicated Vβ families (at least 4 mice for each data point). The higher proportion of NKT cells in the pIV−/− mice leads to an increase in the percentage of Vβ8 and Vβ7 CD4+ T cells. As a result, the representation of most other families is reduced. The distribution of Vβ families in CD8+ T cells is identical between control and pIV−/− mice (lower bar graph).

Since NKT cells display a strong Vβ8 bias in their TCR repertoire,41 Vβ8+ cells are more frequent in the total CD4+ T-cell population of the pIV−/− and MHCII-deficient mice (Figure 7B). Within the CD4+ NK1.1+ population, the same high proportion of Vβ8+ cells is, of course, evident in all strains.

To complete our characterization of the T-cell population in pIV−/− mice, we performed a detailed analysis of the Vβ repertoire of CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes. For each Vβ subset, 4 to 6 pIV−/− mice were compared to an equivalent number of control littermates. No change in the CD8 repertoire was evident in the pIV−/− mice (Figure 7C, lower bar graph). On the other hand, the higher proportion of NKT cells leads to an increase in the representation of Vβ8 and Vβ7 families in the CD4+ T splenocytes of pIV−/− mice (Figure 7C, upper bar graph). The percentages of CD4+Vβ5+ T cells in pIV−/− mice is also marginally increased compared to control mice. This may be explained by the recently described MHCI- and MHCII-independent population of CD4+ T cells.38 This population displays a 6-fold increase in Vβ5 expression and is proportionally increased in pIV−/− mice, given the lack of MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cells. Most of the other Vβ subsets in the CD4+ T-cell compartment of pIV−/− mice are reduced to approximately 50% of the wild-type levels because of the overrepresentation of Vβ families of NKT cells.

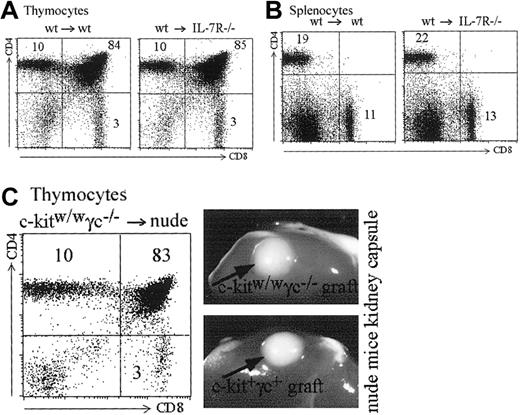

No requirement for IL-7R signaling in MHCII expression by cTECs

The Jak/signal transducers and activators of transription (STAT) pathway is able to activate Mhc2ta transcription through promoter IV. We addressed the question whether the STAT-1,-3,-5 associated cytokine receptors for IL-7 or IL-15 could be implicated in promoter IV activation. It has been previously shown that IL-7 plays an important role in expansion of positively selected T cells.43,44 It has not, however, been shown whether IL-7 or other common gamma chain cytokines are required for MHCII expression in cTECs and hence positive selection of CD4+ T cells. For this purpose, we produced bone marrow chimeras between IL-7R–deficient recipients28 and wild-type bone marrow. In these chimeras, IL-7 production and signaling in thymocytes is normal, but IL-7 cannot induce a signal in cTECs. As shown in Figure8A, such mice show completely normal T-cell development in terms of numbers and CD4/CD8 proportions. Peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cells also are produced in normal numbers and relative frequencies in the spleen (Figure 8B). To address the question of the role of other common gamma chain–associated signals in MHCII expression by cTECs, we analyzed nude mice transplanted with common γ chain, c-kit KO thymuses under the kidney capsule.30 Both type of thymuses developed normally and induced normal selection of CD4+ T cells (Figure 8C). These results rule out an absolute requirement of IL-7R or any of the common gamma chain–associated cytokine signals in cTECs for MHCII expression (see “Discussion”).

IL-7 and common gamma chain–associated signals are dispensable for MHCII expression by cTECs.

(A-B) Bone marrow chimeras were generated with wild-type bone marrow and either wild-type or IL-7R–deficient recipients. (A) Reconstituted thymuses from wild-type or IL-7R–deficient recipients contain the same absolute numbers of thymocytes (4.5 × 107 cells in both thymuses). Thymic subpopulations are strictly identical (compare left and right panels). (B) Total cell counts were identical in the spleens of the wild-type and IL-7R–deficient recipients (5.4 × 107 and 5.5 × 107 cells, respectively). Left and right panels show identical proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the 2 spleens. (C) A c-kit, γc-deficient thymus transplanted under the kidney capsule of a nude mouse generates CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ thymocytes in normal proportions. Photographs show the similar size of wild-type and c-kit, γc-deficient thymuses transplanted into the nude hosts.

IL-7 and common gamma chain–associated signals are dispensable for MHCII expression by cTECs.

(A-B) Bone marrow chimeras were generated with wild-type bone marrow and either wild-type or IL-7R–deficient recipients. (A) Reconstituted thymuses from wild-type or IL-7R–deficient recipients contain the same absolute numbers of thymocytes (4.5 × 107 cells in both thymuses). Thymic subpopulations are strictly identical (compare left and right panels). (B) Total cell counts were identical in the spleens of the wild-type and IL-7R–deficient recipients (5.4 × 107 and 5.5 × 107 cells, respectively). Left and right panels show identical proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the 2 spleens. (C) A c-kit, γc-deficient thymus transplanted under the kidney capsule of a nude mouse generates CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ thymocytes in normal proportions. Photographs show the similar size of wild-type and c-kit, γc-deficient thymuses transplanted into the nude hosts.

Discussion

Expression of pIV in cTECs is controlled by an unknown IFNγ-independent stimulus

Our results with the pIV−/− mice are consistent with previous studies showing that positive selection of CD4+ T cells is driven mainly by MHCII+ cTECs. For instance, positive selection of CD4+ T cells can be restored in an otherwise MHCII negative host if the MHCII molecules are present exclusively on cortical thymic epithelium.45-47 Bone marrow–derived, MHCII+ APCs are largely unable to promote CD4+ T-cell selection. Targeted expression of MHCII in DCs fails to promote positive selection of CD4+ T cells.34 MHCII-deficient mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow also demonstrated that MHCII+ APCs are unable to promote positive selection of CD4+ T cells.48

While MHCII expression is constitutive on cTECs in vivo, this expression is lost when the cells are removed from the thymus and maintained in 2-dimensional cultures in vitro.49 This implies that there is a signal in the thymic microenvironment that maintains MHCII expression turned on in cTECs. The nature of this signal remains unknown. The pathway mediating IFNγ-induced CIITA expression is functional in thymic stromal cell lines and freshly isolated cTECs.50,51 However, MHCII expression on cTECs is maintained in the absence of IFNγ if they are cultured as 3-dimensional reaggregate thymus organ cultures (RTOCs).52In vivo, MHCII expression on cTECs also is independent of IFNγ signaling, as CD4+ T-cell selection is not impaired in IFNγ-deficient or IFNγ receptor–deficient mice.53,54This implies that a signaling pathway distinct from IFNγ drives MHCII expression on cTECs in vivo and in RTOCs. Thymic lobes depleted of thymocytes by deoxyguanosine treatment have been shown to contain MHCII+ cTECs.55 However, both mesenchymal cells and thymocytes are required for differentiation of functional cTECs.52,56 Therefore, there are 3 types of cells that can be responsible for the signals leading to induction of MHCII molecules on cTECs: (1) signals from the mesenchyme, (2) autocrine signals from cTECs, and (3) signals from thymocytes. Both thymocytes and cTECs produce a variety of cytokines and express several cytokine receptors. Since the Jak/STAT and interferon regulatory factor (IRF) pathways have been implicated in promoter IV induction (see next paragraph), the most likely candidates for induction of MHCII expression in cTECs are chemokine receptor signals. Thymic differentiation has been analyzed in many different single- or double-KO mice for cytokines or their receptors (for review, see Ritter and Boyd57 and Rodewald and Fehling58). The most striking effect on thymocytes development was seen in IL-7 knock-out mice, but as shown in Figure 8 this pathway is not required for the induction of MHCII on cTECs. Most other single gene knockouts are also able to sustain positive selection of thymocytes, including IL-1β, IL-1R, interleukin-1 beta–converting enzyme (ICE), IL-2, IL-2Rα or β, IL-3, IL-4, IL-2 + 4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-7R, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, tumor necrosis factors I and II receptor (TNFRI or TNFRII), LT, TNF+LT, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1), granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF), flk-2, and common beta-chain knock-outs. It is thus likely that if cytokines are implicated in MHCII expression by cTECs, then they are redundant.

At the promoter level, 2 transcription factors (STAT1 and IRF1) have been shown to be involved in IFNγ-induced CIITA expression by binding, respectively, to the γ-interferon activating factor (GAS) and interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE)cis-acting elements present in pIV of theMhc2ta gene.19,20 Other members of the STAT and IRF families could potentially also bind to these GAS and ISRE sequences.59-61 However, positive selection of CD4+ T cells is not impaired in any of the STAT and IRF mutants described to date. These comprise mice deficient for STAT1,62,63 STAT2,64 STAT4,65,66STAT5a, STAT5b,67,68 and STAT6.69-71STAT3-deficient mice die early in embryogenesis, but conditional mutants72 lacking STAT3 expression only in the skin and thymic epithelium are viable. The architecture of the thymic cortex is abnormal in these mutants, but they do not display a specific defect in CD4+ T-cell selection pathway.73 The IRF family of genes comprises 9 members that are all potentially able to bind to ISRE sequences. Positive selection of CD4+ T cells is not impaired in any of the available IRF mutants (IRF-1, IRF-2, IRF3, IRF4, IRF5, IRF6, ISGF3γ, and ICSBP; reviewed in Tanaka et al74). IRF-7–deficient mutants have not yet been described, and it will be interesting to determine whether IRF-7–deficient cTECs can express Mhc2ta and MHCII genes. There are 2 explanations that could account for the preservation of CD4+ T-cell selection in IRF and STAT mutants. First, ISRE/GAS binding factors might be dispensable in cTECs. pIV contains other potential binding sites that may be recognized by as-yet-unidentified transcription factors involved in drivingMhc2ta expression in the thymic stroma. Alternatively, cTECs might express 2 or more IRF and/or STAT factors that can compensate for each other's absence in the single- gene knock-outs. In this respect, it is worth mentioning that IRF-1 has been shown to be able to initiate pIV transcription independently of STAT-1.21 The status of CD4+ T-cell selection in IRF-1 and STAT-1 double-deficient animals remains to be determined.

pIV of the Mhc2ta gene drives MHCII expression on mTECs

pIV was demonstrated to be necessary for CIITA and MHCII expression in radio-resistant, nonhematopoietic cells.25In this study, we further demonstrate that mTECs, radio-resistant cell types of epithelial origin,75 also strictly depend on pIV for MHCII expression. The promiscuous expression of peripheral tissue antigens by mTECs has been shown to promote T-cell negative selection or anergy (reviewed in Kyewski et al76). Transcription of genes encoding peripheral antigens is reduced in mTECs of Aire-deficient mice, altering central tolerance and causing autoimmunity.77 Since MHCII expression by mTECs is required for tolerance induction to several autoantigens,77 it could be anticipated that pIV−/− mice would also develop autoimmune disease. Positive selection would first need to be restored in pIV−/− mice, for instance, by re-expressing CIITA under the control of a cTEC-specific promoter.47 Such an experiment would help to address the consequences of the lack of MHCII expression by mTECs in the presence of conserved negative selection by bone marrow–derived APCs.

The residual CD4+ T-cell population in pIV−/− mice

In pIV−/− mice, the phenotype of the residual CD4+ T cells closely matches that of their counterparts in the Αα−/− mouse. They are characterized by lower levels of TCR and an activated phenotype (CD44+CD54+ CD62Llo). These characteristics do not result from the lack of pIV in T cells, as pIV−/− bone marrow–derived progenitors give rise to normal CD4+ T cells when they are selected in a normal thymus.

In MHCII-deficient mice, NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells account for 40%-45% of the residual CD4+ T cells.78 A 4-color stain (αGalCer, NK1.1, CD4, TCRβ) identified similar populations of NKT cells in pIV−/− and Αα−/− mice. Since MHCII-restricted CD4+T-cell counts are strongly reduced in the absence of positive selection, the total CD4+ T-cell population comprises a high proportion of NKT cells. This explains the bias in TCR Vβ usage among the remaining CD4+ T cells in the Αα−/− and pIV−/− mice (skewing toward the Vβ8 and Vβ7 subsets).41

The 4-color staining also allows identification of the αGalCer–−, NK1.1− population that comprises classical MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cells. This population is decreased to the same extent in pIV−/− and Αα−/− mice. Thus, if any residual positive selection occurs in pIV−/− mice, it is not quantitatively greater than in Αα−/− mice. Moreover, αGalCer− NK1.1−CD4+ T cells in pIV−/− mice are likely to contain a significant proportion of the recently described MHCI- and MHCII-independent CD4+ NK1.1− T cells.38 These cells are characterized by a 6-fold increase in Vβ5. In line with this hypothesis, the Vβ5 family is increased in pIV−/−CD4+ T cells. pIV−/− CD4+ T cells bearing other TCR Vβs are unlikely to be MHCII restricted, since they did not expand in the MHCII+ periphery of pIV−/− mice, even in aged mice (data not shown).

New implications concerning the key role of CIITA pIV

The demonstration that pIV of the CIITA gene plays a crucial role in the generation of CD4+ T cells in the mouse has a number of potential implications for human diseases. First, patients with BLS—including those having a deficiency in CIITA—have low CD4+ T-cell counts. This indicates that human cTECs also depend on CIITA to express MHCII and drive positive selection of CD4+ T cells. Second, the 3 CIITA promoters do not show any polymorphism,79 suggesting that there may be a strong selective advantage in maintaining these promoters invariant. For instance, allelic variations of pIV in humans could have pathologic repercussions on positive selection of CD4+ T cells. Given the phenotype of the pIV−/− mouse, it will be interesting to explore whether allelic variants of pIV or more severe mutations of the Mhc2ta regulatory region could lead to CD4+T-cell lymphopenia in humans. Patients diagnosed with a variety of hereditary immunodeficiency syndromes have been reported to have a reduction in the CD4/CD8 ratio. Common variable immunodeficiency is a heterogeneous condition of unknown etiology for which not all responsible genes have been identified (reviewed in Spickett et al80). It is characterized by reduced serum IgG and, in 30% of the cases, by a reduced CD4/CD8 ratio. Recently, 2 cases of hereditary CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia with normal serum levels were also reported.81 Interestingly both patients presented with extensive warts. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) is a heritable syndrome that is also characterized by extensive warts and is often associated with CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia.82 One or more of these conditions could be associated with mutations in the CIITA regulatory region.

pIV is also responsible for the inducible expression of MHCII on extrahematopoietic cells, a widespread phenomenon that is intimately associated with many normal and pathologic immune responses (reviewed in a number of publications83-89). The strict dependence on pIV of both CD4+ T-cell development and inducible MHCII expression suggests that these 2 features of the immune system may have appeared simultaneously. It also suggests that ectopic MHCII expression may play a more important role in the course of acquired immune responses than was previously believed. We intend to address the role of the inducible expression of MHCII genes in the presence of a normal CD4+ T-cell repertoire by crossing the pIV−/−mouse with a transgenic line expressing CIITA under the control of the keratin14 promoter.

We thank E. Reichmann for the antipankeratin serum and M. Kronenberg for CD1αGalCer tetramers. We are very grateful to H. R. MacDonald, A. Fontana, and T. Suter for valuable discussions.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 27, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1855.

Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Gabriella Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation (W.R., H.A.-O.) and by the Ernst and Lucie Schmidheiny Foundation, the National Center for Competence in Research - Neural Plasticity and Repair (NCCR-NEURO), and the Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Foundation (W.R.). J.-M.W. is recipient of the MD/PhD fellowship from the Roche Research Foundation and of a fellowship generously provided by Professor A. F. Junod (Hopital Cantonal, Geneva, Switzerland).

W.R. and H. A.-O. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Walter Reith, Department of Genetics and Microbiology, University of Geneva, Medical School, 1 rue Michel-Servet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland; e-mail:walter.reith@medecine.unige.ch; and Hans Acha-Orbea, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Lausanne Branch, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Lausanne, 155 ch des Boveresses, 1066 Epalinges, Switzerland; e-mail:hans.acha-orbea@ib.unil.ch.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal