Abstract

Although heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a known complication of intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH), its incidence in medical patients treated with subcutaneous UFH is less well defined. To determine the incidence of HIT in this category of patients, the platelet count was performed at baseline and then every 3 ± 1 days in 598 consecutive patients admitted to 2 medical wards and treated with subcutaneous UFH for prophylactic (n = 360) or therapeutic (n = 238) indications. The diagnosis of HIT was accepted in the case of a platelet drop of 50% or more and either the demonstration of heparin-dependent antibodies or (when this search could not be performed) the combination of the following features: (1) the absence of any other obvious clinical explanation for thrombocytopenia, (2) the occurrence of thrombocytopenia at least 5 days after heparin start, and (3) either the normalization of the platelet count within 10 days after heparin discontinuation or the earlier patient's death due to an unexpected thromboembolic complication. HIT developed in 5 patients (0.8%; 95% CI, 0.1%-1.6%); all of them belonged to the subgroup of patients who received heparin for prophylactic indications. The prevalence of thromboembolic complications in patients with HIT (60%) was remarkably higher than that observed in the remaining 593 patients (3.5%), leading to an odds ratio of 40.8 (95% CI, 5.2-162.8). Although the frequency of HIT in hospitalized medical patients treated with subcutaneous heparin is lower than that observed in other clinical settings, this complication is associated with a similarly high rate of thromboembolic events.

Introduction

After bleeding complications, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is the most important complication of unfractionated heparin (UFH).1-5 It develops in up to 3% of patients treated with UFH as a consequence of an antibody-mediated reaction against the complex heparin/platelet factor 46-9and is associated with a high rate of venous or arterial thrombotic events.1-5,8,10 11

Although considerable progress has been made in our understanding of HIT, it is still unclear whether this complication occurs in all patients treated with UFH, or it is at least partially dependent on patient category and modality of heparin administration.4By reviewing prospective clinical trials on the incidence of HIT in patients receiving UFH, Chong showed a frequency of HIT ranging from 1% to 30% among patients receiving high-dose intravenous heparin, whereas the incidence was lower than 2% in patients receiving low-dose subcutaneous heparin.12 In a pooled analysis of a series of prospective studies evaluating the incidence of HIT, Schmitt and Adelman estimated an incidence of 1.1% and 2.9% with the use of intravenous porcine and bovine heparin, respectively, whereas no cases were observed in patients treated with subcutaneous heparin.13 By contrast, in a substudy of a recent randomized clinical trial on the prevention of postoperative deep vein thrombosis in orthopedic patients, HIT as confirmed by heparin-dependent IgG antibodies developed in 2.7% of patients treated with subcutaneous UFH,3 a rate that is fully consistent with that reported in studies using intravenous heparin. Because the frequency of HIT-IgG formation and the risk of HIT is highly dependent on patient population,4 the results of this substudy do not necessarily translate to other categories of patients.

To estimate the incidence and timing of HIT in hospitalized medical patients requiring the administration of subcutaneous heparin for various indications, we performed a prospective cohort study in 598 consecutive patients admitted to 2 departments of internal medicine. All patients recruited for this investigation were followed for the occurrence of HIT and overt clinical events.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a prospective cohort follow-up study performed to determine the incidence of HIT in hospitalized medical patients receiving subcutaneous UFH, as well as the occurrence of arterial or venous thrombotic events related to this complication. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Padua Unversity. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inception cohort

Consecutive patients admitted to 2 departments of internal medicine of the University Hospital of Padua between November 1997 and July 2000 were eligible for the study provided that they had indications to receive subcutaneous unfractionated calcium heparin for prophylaxis or treatment of arterial or venous thromboembolic diseases. Patients who had received heparin in the previous 3 months were excluded, as were those who had an abnormal baseline platelet count (< 150 × 109/L or > 450 × 109/L), had a myeloproliferative disorder, were receiving radiotherapy or chemotherapy, or had clinical or laboratory findings compatible with disseminated intravascular coagulation, sepsis, liver cirrhosis, hypersplenism, or severe renal insufficiency.

At referral, all patients included in the study had a thorough medical history obtained and underwent a physical examination with particular attention to the presence of an underlying malignancy and any previous exposure to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin.

In patients with medical diseases requiring the prevention of thromboembolism, prophylactic doses of heparin (ranging between 10 000 and 20 000 IU/d) were programmed for variable periods of time, usually covering the entire period of hospitalization. In most patients with acute thromboembolic disorders UFH was administered in doses able to prolong the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 1.5 to 3.0 times the control value, whereas in a minority of patients lower (fixed) doses were used. In most patients UFH was given in combination with oral anticoagulant therapy, the heparin treatment being interrupted when the international normalized ratio reached a value of 2.0 or higher in 2 consecutive determinations. In a minority of patients a longer course of heparin, not followed by oral anticoagulants, was programmed.

Development of HIT

A platelet count was performed at baseline and thereafter every 3 ± 1 days. The diagnosis of HIT was suspected in all cases of a platelet drop of 50% or more of the pretreatment value or any further platelet count during heparin therapy, provided that this was confirmed by a second determination. When possible, a blood sample was obtained for the subsequent determination of heparin-dependent IgG antibodies. The diagnosis of HIT was accepted in the case of either the demonstration of heparin-dependent antibodies or (when this search could not be performed) the combination of the following features: (1) the absence of any other obvious clinical explanation for thrombocytopenia, (2) the occurrence of thrombocytopenia at least 5 days after heparin start, and (3) either the normalization of the platelet count within 10 days after heparin discontinuation or the earlier patient's death due to an unexpected thromboembolic complication. The first day of heparin use was calculated as day 1, and the first day that the platelet count was shown to have fallen by at least 50% was assumed to be the day of HIT occurrence.

Laboratory determination of heparin-dependent antibodies

Blood samples were collected from a brachial vein with a fine needle in sodium citrate 1:10, centrifuged at 10 000g for 3 minutes and stored at −70°C. Both an antigen and an activation assay were performed according to previously described methods.14,15 We used an antigen assay that detects IgG antibodies against platelet factor 4 bound to polyvinylsulfonate (Genetic Testing Institute, Brookfield, WI).14 Visual evaluation of heparin-induced platelet activation (HIPA) was done with the use of the HIPA assay at the Institute for Immunology and Transfusion Medicine of Greifswald (Germany). Heat-inactivated patient serum was incubated in a magnetic stirrer with 2 steel spheres with washed platelets together with heparin in low and high concentration, the transparency of the suspension being considered as a positive result.15

Thromboembolic complications

All included patients were followed until discontinuation of heparin or hospital discharge. The clinical suspicion of venous or arterial thromboembolism was confirmed by the following objective tests: compression ultrasound or venography in case of suspected deep vein thrombosis, ventilation/perfusion lung scanning, spiral computed tomography (CT) or pulmonary angiography in case of suspected pulmonary embolism, electrocardiography with enzymatic support in case of suspected myocardial infarction, and cerebral CT in case of suspected stroke. In case of death, the cause of death was either investigated by autopsy or adjudicated according to the opinion of a physician unaware of the study aims.

Analysis

First, we evaluated the proportion (and its 95% confidence interval [CI]) of patients who developed HIT among all those who were treated with subcutaneous UFH. Then, the cumulative frequency of HIT over time was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier technique. For this purpose, patients were censored at the third day following heparin withdrawal. Patients receiving heparin for the whole period of hospitalization were censored on the day of hospital discharge. In case of an unusual prolongation of heparin treatment, patients were censored after the completion of 45 days of observation.

Odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% CIs were used to describe the association between thromboembolic complications and HIT. An OR was considered to be statistically significant when the lower limit of the 95% CI was more than 1.0.

Results

Patients

Of 949 eligible patients, 351 (37%) were excluded because of recent heparin administration (n = 140), an abnormal platelet count at baseline (n = 131), an oncohematologic disease (n = 58), liver cirrhosis (n = 11), septicemia (n = 5), concomitant chemotherapy (n = 4), or disseminated intravascular coagulation (n = 2).

Therefore, 598 patients were included in the study. The main demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients are shown in Table 1. More than 60% of included patients (360 of 598) received heparin for prophylactic indications. When considering the dosage administered in the first 2 days, 87 patients (14%) received 10 000 IU daily, 303 patients (51%) 15 000 IU daily, and the remaining 208 (35%) a dosage higher than 15 000 IU daily. Of the 598 patients, 195 patients (32.6%) had previous (at least 3 months earlier) administration of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin.

Main characteristics of the patients included in the study

| Features . | Prophylaxis group, n = 360* . | Treatment group, n = 238† . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of men | 148 (41.1%) | 118 (49.6%) |

| Age, y, median (range) | 76 (18-96) | 73 (25-95) |

| Active cancer | 59 (16.4%) | 13 (5.5%) |

| Previous heparin treatment‡ | 105 (29.2%) | 90 (37.8%) |

| Daily heparin dosage, IU, median (range) | 15 000 (10 000-20 000) | 25 000 (15 000-40 000) |

| Heparin duration, d, median (range) | 14 (5-45) | 10 (5-32) |

| Features . | Prophylaxis group, n = 360* . | Treatment group, n = 238† . |

|---|---|---|

| No. of men | 148 (41.1%) | 118 (49.6%) |

| Age, y, median (range) | 76 (18-96) | 73 (25-95) |

| Active cancer | 59 (16.4%) | 13 (5.5%) |

| Previous heparin treatment‡ | 105 (29.2%) | 90 (37.8%) |

| Daily heparin dosage, IU, median (range) | 15 000 (10 000-20 000) | 25 000 (15 000-40 000) |

| Heparin duration, d, median (range) | 14 (5-45) | 10 (5-32) |

Indications for heparin administration: immobilization in 160, heart diseases in 75, rheumatic diseases in 55, respiratory failure in 38, infectious diseases in 19, and recent minor surgery in 13.

Indications for heparin administration: venous thromboembolism in 153 (deep vein thrombosis alone or associated with pulmonary embolism in 116, pulmonary embolism alone in 22, superficial thrombophlebitis in 15); arterial thromboembolism in 85 (acute myocardial infarction in 13, unstable angina in 32, arterial embolism in 40).

More than 3 months earlier.

HIT

During hospitalization, 11 patients (1.8%) developed a platelet drop of at least 50%, confirmed by a second determination. Either the antigenic or the functional assay was positive in 3 of the 9 patients tested for the presence of heparin-dependent antibodies. The diagnosis of HIT was accepted also in the 2 patients in whom the antibody determination could not be done. Indeed, thrombocytopenia occurred more than 5 days after heparin start; all conditions potentially responsible for nonimmune thrombocytopenia (hemodilution from fluids/blood, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, other drug reactions, etc) could be excluded; in one patient the platelet count normalized within 1 week, and the other died in temporal association with the acute platelet fall because of an unexpected ischemic stroke. Thus, according to the predefined criteria, the rate of HIT in our cohort was 5 of 598 (0.8%; 95% CI, 0.1%-1.6%).

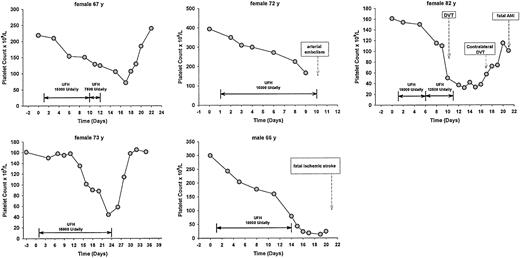

All patients who developed HIT belonged to the group of 360 (1.4%; 95% CI, 0.5%-3.2%) who had been given heparin for prophylactic indications. The main features of these 5 patients are shown in Table 2 and Figure1. HIT developed in 1 of the 87 patients (1.1%) who received an initial dose of UFH of 10 000 IU daily, 4 of the 303 (1.3%) who received 15 000 IU daily, and in none of the 208 (0.0%) who received an initial dose higher than 15 000 IU daily. Previous exposure to heparin (> 3 months earlier), which was identified in 195 patients, did not increase the frequency of developing HIT: 0 of 195 (0.0%) versus 5 of 403 (1.2%).

Main features of the 5 patients with HIT

| IN . | Age, y . | Sex . | Indication for UFH . | Initial daily dose, IU . | Previous heparin . | Time to HIT, d . | Antibody assay . | Platelet count, × 109/L, base/nadir . | Thromboembolism . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 14 | Positive | 219/72 | No |

| 2 | 72 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 8 | Positive | 394/166 | Arterial embolism |

| 3 | 82 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 9 | Positive | 161/32 | Bilateral deep vein thrombosis, fatal myocardial infarction |

| 4 | 66 | M | Prophylaxis | 10 000 | No | 13 | Not performed | 300/13 | Fatal stroke |

| 5 | 73 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 22 | Not performed | 161/44 | No |

| IN . | Age, y . | Sex . | Indication for UFH . | Initial daily dose, IU . | Previous heparin . | Time to HIT, d . | Antibody assay . | Platelet count, × 109/L, base/nadir . | Thromboembolism . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 14 | Positive | 219/72 | No |

| 2 | 72 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 8 | Positive | 394/166 | Arterial embolism |

| 3 | 82 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 9 | Positive | 161/32 | Bilateral deep vein thrombosis, fatal myocardial infarction |

| 4 | 66 | M | Prophylaxis | 10 000 | No | 13 | Not performed | 300/13 | Fatal stroke |

| 5 | 73 | F | Prophylaxis | 15 000 | No | 22 | Not performed | 161/44 | No |

Clinical course of the 5 patients who developed HIT.

DVT indicates deep vein thrombosis; and AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

Clinical course of the 5 patients who developed HIT.

DVT indicates deep vein thrombosis; and AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

No patient developed HIT within the first week. The cumulative incidence of HIT was 0.38% (95% CI, 0%-0.95%) after 10 days, 1.04% (95% CI, 0%-2.36%) after 15 days, 1.04% (95% CI, 0%-2.87%) after 20 days, 2.12% (95% CI, 0%-6.12%) after 1 month, and then remained stable (Figure 2).

Symptomatic thromboembolic complications

Three of the 5 patients who developed HIT (60%) experienced clinically symptomatic thromboembolic complications in temporal association with the occurrence of HIT (fatal ischemic stroke, bilateral deep venous thrombosis followed by fatal acute myocardial infarction, and acute lower limb arterial occlusion, respectively). Thromboembolic complications were recorded also in 21 patients who did not develop HIT (venous thromboembolism in 17, ischemic stroke in 2, acute myocardial infarction in 1, arterial embolism in 1), and were fatal in 2.

The incidence of thromboembolic events in patients who developed HIT was remarkably higher than that observed in patients who did not (21 of 593, 3.5%; OR = 40.8; 95% CI, 5.2%-162.8%). In no patients belonging to the latter group did the platelet count decrease during or following the thromboembolic complication.

Discussion

Despite the growing availability of low-molecular-weight heparins, UFH is still widely used for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombotic disorders, especially in the United States.16-18 The results of our study show that the incidence of HIT in hospitalized medical patients treated with subcutaneous UFH (0.8%; 95% CI, 0.1%-1.6%) is lower than that observed in other settings, that is, patients treated with intravenous heparin,12,13,18 and patients treated with subcutaneous heparin for prevention of postoperative deep vein thrombosis in orthopedic surgery.3 However, it is associated with a similarly high rate of thromboembolic events.

This complication peculiarly affected patients requiring a subcutaneous heparin course longer than 1 week, and its rate increased according to the duration of treatment. Noteworthy, all cases of HIT belonged to the cohort of patients who had been given heparin for prophylactic indications, whereas no cases of HIT were observed among patients requiring shorter courses of heparin for therapeutic indications. Because in recent years concern about the risk for late venous thromboembolic complications has led investigators and clinicians to consider extending the duration of prophylaxis beyond the first week in a broad spectrum of indications,16 operators should be alerted about the risk of this potentially serious complication whenever UFH is scheduled.

As expected, the risk of thrombotic complications in patients developing HIT was high. Three of the 5 patients who developed HIT experienced one or more episodes of either arterial or venous thrombotic complications, which were fatal in 2. This frequency was far higher than that observed in the remaining patients of our cohort. Our data are fully consistent with those recently reported by Warkentin and associates in a surgical field3 and strongly suggest that even in hospitalized medical patients the occurrence of threatening arterial or venous thrombotic complications is to be expected in a substantial proportion of all patients who develop immune HIT.

A number of methodologic issues require careful analysis. First, because we did not perform a search for heparin-dependent antibodies in all patients, we cannot exclude that the formation of IgG occurred in a proportion of patients higher than that identified. However, the purpose of our investigation was to make an estimate of the risk of clinically relevant HIT in medical inpatients receiving subcutaneous UFH. The formation of antibodies does not necessarily predict the development of this clinical syndrome.4 Second, because we labeled as having HIT also 2 patients in whom the antibody determination could not be performed, the rate of this complication might have been overestimated. However, the stringent clinical criteria we adopted in the substitution for the antibody determination makes it very likely to label these 2 patients as having HIT. Third, because at the time of planning and performing our study we were unaware of the possible delayed onset of HIT and thrombosis,19,20patients had no further clinical and laboratory surveillance after the third day following heparin discontinuation, nor were they followed after hospital discharge. Accordingly, the rate of HIT following the administration of subcutaneous HIT in medical inpatients could be higher than that reported in the current investigation. Our study results are likely to reflect the true risk of clinically important HIT exhibited by hospitalized medical patients during the administration of subcutaneous UFH or soon after its discontinuation. The validity of our approach is confirmed by the high prevalence of unexpected thromboembolic complications among patients labeled as affected by HIT, which fully compares with that recorded in literature,1-5,8,10 11 but contrasts with that observed in the remaining patients of our cohort.

We believe that the results of our study are widely applicable because consecutive patients with a broad spectrum of medical diseases requiring prophylactic or therapeutic administration of heparin were included and prospectively followed until hospital discharge. Confounding factors were minimized by excluding patients recently exposed to heparin as well as those suffering from diseases potentially responsible for nonimmune thrombocytopenia. For the definition of HIT, sensitive and specific criteria were adopted. The determination of heparin-dependent IgG antibodies was performed with the use of validated activation and antigen assays. Finally, all suspected thromboembolic events were objectively confirmed.

In conclusion, our study suggests that HIT and HIT-related thromboembolic complications are relatively common adverse effects of subcutaneous UFH treatment in medical patients and are to be expected in all patients in whom heparin administration persists beyond the first week of treatment. Because this approach has become regular clinical practice in a broad spectrum of conditions essentially for prophylactic indications, we recommend close clinical and laboratory surveillance in all patients who are candidates for long courses of UFH. As an alternative, in clinical practice it is advisable to replace UFH with low-molecular-weight heparins because these compounds have been shown, at least in surgical patients, to be associated with a lower incidence of this complication, while still retaining at least a similar thromboprophylactic effect.3 We think, however, that proper clinical investigations should be done to assess the true risk of HIT in medical patients requiring long-term courses of these drugs for prophylactic indications.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 12, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2201.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Paolo Prandoni, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, 2nd Chair of Internal Medicine, Via Ospedale Civile, 105 35128 Padua, Italy; e-mail: paoprand@tin.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal