Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) may arise during long-term follow- up of aplastic anemia (AA), and many AA patients have minor glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor–deficient clones, even at presentation. PIG-A gene mutations in AA/PNH and hemolytic PNH are thought to be similar, but studies on AA/PNH have been limited to individual cases and a few small series. We have studied a large series of AA patients with a GPI anchor–deficient clone (AA/PNH), including patients with minor clones, to determine whether their pattern of PIG-A mutations was identical to the reported spectrum in hemolytic PNH. AA patients with GPI anchor–deficient clones were identified by flow cytometry and minor clones were enriched by immunomagnetic selection. A variety of methods was used to analyzePIG-A mutations, and 57 mutations were identified in 40 patients. The majority were similar to those commonly reported, but insertions in the range of 30 to 88 bp, due to tandem duplication of PIG-A sequences, and deletions of more than 10 bp were also seen. In 3 patients we identified identical 5-bp deletions by conventional methods. This prompted the design of mutation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers, which were used to demonstrate the presence of the same mutation in an additional 12 patients, identifying this as a mutational hot spot in thePIG-A gene. Multiple PIG-A mutations have been reported in 10% to 20% of PNH patients. Our results suggest that the large majority of AA/PNH patients have multiple mutations. These data may suggest a process of hypermutation in the PIG-A gene in AA stem cells.

Introduction

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired clonal stem-cell disorder characterized by hemoglobinuria, intravascular hemolysis, and venous thrombosis.1 A subset of cell-surface proteins are attached to the plasma membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. In PNH, due to somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, the biosynthesis of the GPI anchor is deficient in affected cells and GPI-anchored proteins are absent from the cell surface.2 3

A strong connection between aplastic anemia (AA) and PNH was first commented on by Dacie and Lewis.4,5 Patients with AA may be observed to develop PNH, often accompanied by improvements in their peripheral blood counts, whereas PNH patients sometimes develop AA with loss of the PNH clone. With the introduction of routine Ham testing of AA patients, it was discovered that many AA patients developed a PNH clone even in the absence of clinically observable hemolytic disease, leading to a distinction between hemolytic PNH and AA/PNH. Large-scale studies have observed an incidence of PNH clones in AA patients surviving after antilymphocyte globulin (ALG) of 10% to 25% at 15 years after presentation.6 7

The introduction of flow cytometry to detect the absence of GPI-anchored proteins on PNH cells has led to further revelations. We and others have observed that many AA patients already have a detectable PNH clone at presentation, but usually at low level and detectable in granulocytes or monocytes but often not in erythrocytes.8-11

It is now clear that most, if not all, PNH clones arise because of somatic mutation in the PIG-A gene.12 A variety of mutations have been reported, mostly base substitutions and small deletions and insertions leading to frameshifts.3 Previous studies have concentrated on primary hemolytic PNH patients, although occasional patients with AA/PNH have been described, and 2 small studies have specifically looked at AA/PNH patients.13,14Overall, the AA/PNH population previously studied is likely to have an ascertainment bias toward patients with a positive Ham test and patients who have evolved a large population of affected cells, whereas many AA patients have a small clone detectable in their granulocytes but often not in their red cells.8,10,11 As part of a European Community study on the pathophysiology of AA, we wished to examine the spectrum of mutations specifically in AA patients developing a PNH clone. Patients were identified by flow cytometric screening and GPI anchor–negative cells were enriched by immunomagnetic separation, so as not to exclude patients with only a small clone. We report here that in this large series (40 patients) the spectrum of mutations resembled, but had some distinct differences from, that published for primary PNH, and that it included a major mutational hot spot. Although a significant minority of PNH patients are known to carry more than one clone,15 our results imply that in patients with AA/PNH the large majority have more than one PNH clone.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Patients with an initial diagnosis of acquired AA were screened in participating centers for the presence of GPI anchor–deficient cells. There were 40 patients who showed evidence of deficient cells, either at presentation or after variable periods of follow-up, and were referred to this study. Blood samples were obtained after informed consent under the auspices of the institutional review board at the University of Ulm, and boards at each participating center. Patient characteristics are listed in Table1.

Patient details

| Patient no. . | Sex . | Diagnosis . | FBC at diagnosis . | Time to study, y . | FBC at study . | Thrombosis, Y/N . | Treatment . | Response . | Transfusion, Y/N . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb . | Neut . | Plts . | Hb . | Neut . | Plts . | ||||||||

| 1 | M | SAA | 4.5 | 2.2 | 5.0 | < 0.1 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 5.0 | N | csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 2 | M | nSAA | 8.7 | 2.0 | 21.0 | 6 | 10.4 | 7.3 | 67.0 | Y* | ALG, csa | PR | N |

| 3 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 2 | 11.4 | 0.8 | 23.0 | N | ALG, csa | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 4 | F | SAA | 9.1 | 0.8 | 17.0 | 9 | 9.1 | 1.0 | 54.0 | N | ATG, csa | PR | N |

| 5 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 6 | M | vSAA | na | na | na | 0.2 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 7 | M | vSAA | na | na | na | 0.4 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 8 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 9 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 10 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 3 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 11 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 5 | 10.4 | 4.0 | 159.0 | N | csa | PR | N |

| 12 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 13 | F | SAA | na | na | na | 0.2 | na | na | na | na | ALG, csa, G-CSF | na | na |

| 14 | F | SAA | na | na | na | 4 | 11.4 | 3.6 | 84.0 | N | ALG, csa | PR | N |

| 15 | F | vSAA | 7.7 | 0.1 | 10.0 | 3 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 31.0 | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR† | Y (red + plts) |

| 16 | F | nSAA | 10.0 | 1.2 | 20.0 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 1.5 | 90.0 | ?‡ | csa | na | Y (red + plts) |

| 17 | F | nSAA | 8.5 | 0.8 | 28.0 | 0.7 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 47.0 | N | ALG, csa | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 18 | F | SAA | 8.1 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.9 | 10.0 | N | ALG, csa | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 19 | F | nSAA | 6.9 | 0.6 | 12.0 | 14 | 8.4 | 1.1 | 27.0 | N | Metenolon | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 20 | M | AA | 9.9 | 0.7 | 28 | 5 | 13.4 | 5.2 | 165 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | CR | N |

| 21 | M | AA | 7 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 2.6 | 56 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | PR | N |

| 22 | M | AA | 8 | 0.6 | 13 | 3 | 12.9 | 2.2 | 75 | Y | ALGx2, csa | PR | N |

| 23 | F | AA | 10.5 | 0.9 | 10 | 15 | 10.4 | 0.6 | 39 | N | ALG, oxy | PR | N |

| 24 | M | AA | na | na | na | 10 | 11.9 | 2 | 64 | Y | ALGx2, oxy | N/A | N |

| 25 | M | AA | 11.8 | 1.3 | 36 | 7 | 15.1 | 2.4 | 119 | N | ALGx2, csa | PR | N |

| 26 | M | AA | 6 | < 0.1 | 10 | 1.2 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 26 | N | ALG, GCSF, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 27 | M | AA | 7.1 | 0.8 | 7 | 3 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 10 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 28 | M | AA | 6.1 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 22 | N | ALGx2, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 29 | F | AA | 10 | 1.1 | 30 | 4 | 11.4 | 1.8 | 89 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | N |

| 30 | F | AA | 5.1 | 0.3 | 9 | 26 | 10.7 | 0.5 | 20 | N | pred, oxy | NR | Y(red) |

| 31 | F | AA | 4.5 | 0.5 | 18 | 3 | 8.7 | 3.6 | 197 | N | ALG, csa | PR | Y(red) |

| 32 | M | AA | 6 | 0.4 | 13 | 7 | 13.1 | 2.4 | 125 | N | ALG, oxy | PR | N |

| 33 | F | AA | 8.2 | 2.5 | 50 | 10 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 17 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | Y(red) |

| 34 | F | AA | na | na | na | 13 | 8.8 | 1 | 95 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | PR | Y(red) |

| 35 | M | AA | 5.8 | 0.5 | 14 | 0.2 | 10 | 1.1 | 74 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | Y(red + plts) |

| 36 | M | AA | 8.7 | na | 40 | 34 | 13 | 2.9 | 115 | N | csa | PR | N |

| 37 | M | AA | na | na | na | 5 | 7.8 | 0.4 | 41 | N | csa | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 38 | F | AA | 5.7 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.3 | 14 | 6.3 | 15 | N | ALG, G-CSF | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 39 | M | AA | na | na | na | 2 | 10 | 0.3 | 4 | N | ALG, csa | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 40 | F | AA | na | na | na | 5 | 11 | 1.7 | 223 | N | ALGx2, csa | R | N |

| Patient no. . | Sex . | Diagnosis . | FBC at diagnosis . | Time to study, y . | FBC at study . | Thrombosis, Y/N . | Treatment . | Response . | Transfusion, Y/N . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb . | Neut . | Plts . | Hb . | Neut . | Plts . | ||||||||

| 1 | M | SAA | 4.5 | 2.2 | 5.0 | < 0.1 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 5.0 | N | csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 2 | M | nSAA | 8.7 | 2.0 | 21.0 | 6 | 10.4 | 7.3 | 67.0 | Y* | ALG, csa | PR | N |

| 3 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 2 | 11.4 | 0.8 | 23.0 | N | ALG, csa | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 4 | F | SAA | 9.1 | 0.8 | 17.0 | 9 | 9.1 | 1.0 | 54.0 | N | ATG, csa | PR | N |

| 5 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 6 | M | vSAA | na | na | na | 0.2 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | PR | Y (red + plts) |

| 7 | M | vSAA | na | na | na | 0.4 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 8 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 9 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 10 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 3 | na | na | na | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR | N |

| 11 | M | SAA | na | na | na | 5 | 10.4 | 4.0 | 159.0 | N | csa | PR | N |

| 12 | F | SAA | na | na | na | < 0.1 | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 13 | F | SAA | na | na | na | 0.2 | na | na | na | na | ALG, csa, G-CSF | na | na |

| 14 | F | SAA | na | na | na | 4 | 11.4 | 3.6 | 84.0 | N | ALG, csa | PR | N |

| 15 | F | vSAA | 7.7 | 0.1 | 10.0 | 3 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 31.0 | N | ALG, csa, G-CSF | CR† | Y (red + plts) |

| 16 | F | nSAA | 10.0 | 1.2 | 20.0 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 1.5 | 90.0 | ?‡ | csa | na | Y (red + plts) |

| 17 | F | nSAA | 8.5 | 0.8 | 28.0 | 0.7 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 47.0 | N | ALG, csa | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 18 | F | SAA | 8.1 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.9 | 10.0 | N | ALG, csa | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 19 | F | nSAA | 6.9 | 0.6 | 12.0 | 14 | 8.4 | 1.1 | 27.0 | N | Metenolon | CR | Y (red + plts) |

| 20 | M | AA | 9.9 | 0.7 | 28 | 5 | 13.4 | 5.2 | 165 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | CR | N |

| 21 | M | AA | 7 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 2.6 | 56 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | PR | N |

| 22 | M | AA | 8 | 0.6 | 13 | 3 | 12.9 | 2.2 | 75 | Y | ALGx2, csa | PR | N |

| 23 | F | AA | 10.5 | 0.9 | 10 | 15 | 10.4 | 0.6 | 39 | N | ALG, oxy | PR | N |

| 24 | M | AA | na | na | na | 10 | 11.9 | 2 | 64 | Y | ALGx2, oxy | N/A | N |

| 25 | M | AA | 11.8 | 1.3 | 36 | 7 | 15.1 | 2.4 | 119 | N | ALGx2, csa | PR | N |

| 26 | M | AA | 6 | < 0.1 | 10 | 1.2 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 26 | N | ALG, GCSF, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 27 | M | AA | 7.1 | 0.8 | 7 | 3 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 10 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 28 | M | AA | 6.1 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 22 | N | ALGx2, csa | NR | Y (red + plts) |

| 29 | F | AA | 10 | 1.1 | 30 | 4 | 11.4 | 1.8 | 89 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | N |

| 30 | F | AA | 5.1 | 0.3 | 9 | 26 | 10.7 | 0.5 | 20 | N | pred, oxy | NR | Y(red) |

| 31 | F | AA | 4.5 | 0.5 | 18 | 3 | 8.7 | 3.6 | 197 | N | ALG, csa | PR | Y(red) |

| 32 | M | AA | 6 | 0.4 | 13 | 7 | 13.1 | 2.4 | 125 | N | ALG, oxy | PR | N |

| 33 | F | AA | 8.2 | 2.5 | 50 | 10 | 8.3 | 1.6 | 17 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | Y(red) |

| 34 | F | AA | na | na | na | 13 | 8.8 | 1 | 95 | N | ALGx2, oxy, csa | PR | Y(red) |

| 35 | M | AA | 5.8 | 0.5 | 14 | 0.2 | 10 | 1.1 | 74 | N | Nil | N/A1-153 | Y(red + plts) |

| 36 | M | AA | 8.7 | na | 40 | 34 | 13 | 2.9 | 115 | N | csa | PR | N |

| 37 | M | AA | na | na | na | 5 | 7.8 | 0.4 | 41 | N | csa | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 38 | F | AA | 5.7 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.3 | 14 | 6.3 | 15 | N | ALG, G-CSF | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 39 | M | AA | na | na | na | 2 | 10 | 0.3 | 4 | N | ALG, csa | NR | Y(red + plts) |

| 40 | F | AA | na | na | na | 5 | 11 | 1.7 | 223 | N | ALGx2, csa | R | N |

FBC indicates full blood count; Hb, hemoglogin levels; Neut, neutrophil counts; Plts, platelets; AA, aplastic anemia; SAA, severe AA; csa, cyclosporin; PR, partial response (response defined as per Consensus Conference on Treatment of Aplastic Anaemia); red, red-cell transfusions; nSAA, nonsevere AA; na, not available; vSAA, very severe AA; CR, complete response; oxy, oxymetholone; pred, prednisolone; N/A, not applicable; and NR, no response.

Portal vein thrombosis.

Relapsed at time of study, retreated with ATG, csa, G-CSF and achieved PR.

? Abdominal pain crises, possibly due to mesenterial vessel thrombosis.

Studied before treatment started.

Cell separation and DNA and RNA extraction

Peripheral blood granulocytes and mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated on Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) by gradient centrifugation. Erythrocytes were separated from granulocytes by sedimentation using 5% dextran. DNA and RNA were extracted from the fractionated white cells using Tri Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom), following the manufacturer's protocol.

Acidified serum lysis (Ham) test

The Ham test was performed using a standard protocol.16 Briefly, erythrocytes were incubated with acidified normal human AB serum at pH levels of 6.6 to 7.0 for one hour at 37°C. Higher than 2% lysis was scored as positive. Normal erythrocytes and aminoethylisothiouronium bromide (AET)-treated erythrocytes were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Quantification of GPI-linked surface proteins

Analysis of the GPI-anchored membrane proteins on granulocytes, MNCs, and red blood cells (RBCs) was performed by flow cytometry, using monoclonal antibodies specific to CD55, CD59, and CD66b. In brief, 5 μL of appropriate monoclonal antibody was added to 1 × 106 white cells and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were given 2 washes and incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). After final washes the cells were fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom). Quantitation of the expression of surface GPI-anchored proteins was carried out using LYSYS II version 1.1 software (BD Biosciences).

Immunomagnetic enrichment of PNH cells

GPI anchor–positive cells were depleted with immunomagnetic beads. Granulocytes (or lymphocytes) were labeled with anti-CD59 antibody. Sensitized cells were bound to goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) by incubation and gentle mixing at 4°C. Initial experiments used 30 minutes incubation, but better results were obtained with longer incubation, and for most experiments overnight incubation was used. Bead-positive cells were depleted using a magnetic particle concentrator, leaving the CD59− cells enriched in the supernatant. The results of enrichment were assessed by flow cytometry after relabeling cells with anti-CD59 antibody.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), subcloning, and sequencing

DNA was amplified with the proofreading polymerase Pfu using the primers shown in Table 2 (“Primers used for cloning and sequencing of exon 2”), which generated 2 overlapping fragments for exon 2.

PCR primers

| Primers/primer ID . | Sequence 5′ → 3′ . | Location . | Annealing temperature, °C . | Product size, bp . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers used for cloning and sequencing of exon 2 | ||||

| S-2A | TGA GCT GAG ATC CTG TTT TAC TCT | Intron 1 | 55 | 474 |

| AS-2A | TGA ATG GAT TAT CGT GAC TCT CTC | Exon 2 | 55 | |

| S-2B | TGC CAT TGC TCA GGT ACA TAT TT | Exon 2 | 55 | 445 |

| AS-2B | TCA ACA GCT TTC TAT AGG GAA AAA | Intron 2 | 55 | |

| Primers used for PCR, SSCP, and direct sequencing of exons 2 to 6 | ||||

| S-21 | GTGTTTTTGTTTCTGAGCTGAGAT | Intron 1 | 60 | 251 |

| AS-22 | CGCCTCCCATATTTGGGTAG | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-23 | AGAACCCGTACCCATAATATATG | Exon 2 | 60 | 311 |

| AS-11 | GAAAAAGAACTATGTGAATGGAT | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-24 | GCTCAGGTACATATTTGTTCGGG | Exon 2 | 60 | 269 |

| AS-25 | TTTCAGGATTCAGTGCTGCTC | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-26 | TGTGATACAAACCACATCATTTG | Exon 2 | 60 | 274 |

| AS-13 | GCCAAACAATCATTATATACAAG | Intron 2 | 60 | |

| S-17* | TGGATTCTCAGTCGTTCTGGTGA | Intron 2 | 60 | 244 |

| AS-18 | CTTCTCCCTCAAGACAACATGAA | Intron 3 | 60 | |

| S-5 | TCACTCCTTTCTTCCCCTCTC | Intron 3 | 58 | 267 |

| AS-14 | AATCCCAACCATGAATGCCCTC | Intron 4 | 58 | |

| S-15 | TCTTCCTGAGGTATGATTATGGTG | Intron 4 | 57 | 298 |

| AS-16 | AAGAGTTCAGACACAATCTTTTCTC | Intron 5 | 57 | |

| S-19* | GGTCATTGTTATCATGGGACAG | Intron 5 | 58 | 361 |

| AS-20 | TCTTACAATCTAGGCTTCCTTC | Intron 6 | 58 | |

| Primers used for RT-PCR of PIG-A fragments for SSCP | ||||

| S-35 | CTC TAA GAA CTG ATG TCT AAA CCG | NA | NA | 176 |

| As-22 | C GCC TCC CAT ATT TGG GTA G | NA | NA | |

| S-23 | AGA ACC CGT ACC CAT AAT ATA TG | NA | NA | 311 |

| As-11 | GAA AAA GAA CTA TGT GAA TGG AT | NA | NA | |

| S-24 | GCT CAG GTA CAT ATT TGT TCG GG | NA | NA | 269 |

| As-25 | TTT CAG GAT TCA GTG CTG CTC | NA | NA | |

| S-26 | TGT GAT ACA AAC CAC ATC ATT TG | NA | NA | 242 |

| As-36 | TCT GGA TAT TTC TGA CAG AGT TCA G | NA | NA | |

| S-38 | ATT GTT GTT GTC AGC AGA CTT G | NA | NA | 333 |

| AsPIG-Ae | CTC AGG AAT TCC ACC AAC TCT | NA | NA | |

| S-40 | GCA TGG CGA TCG TGG AAG CAG | NA | NA | 293 |

| As-41 | TCG TTT GTC CAT TGG CAA CAC AGC | NA | NA | |

| S-30 | CTG AAG TCA GGG ACA TTG CC | NA | NA | 381 |

| As-20 | TCT TAC AAT CTA GGC TTC CTT C | NA | NA | |

| Primers for 1st and 2nd round mutation-specific PCR | ||||

| SD-1 | GTA AGG AAA ATA CTA AG | Exon 2 | 48 | 188 |

| ASD-1 | AGT CTA CAA TGC AAT TA | Intron 2 | 48 | |

| SD-2 | GTA AGG AAA ATA CTA AG | Exon 2 | 48 | 168 |

| ASD-2 | CTA TCA TTT CAT TAC CT | Intron 2 | 48 |

| Primers/primer ID . | Sequence 5′ → 3′ . | Location . | Annealing temperature, °C . | Product size, bp . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers used for cloning and sequencing of exon 2 | ||||

| S-2A | TGA GCT GAG ATC CTG TTT TAC TCT | Intron 1 | 55 | 474 |

| AS-2A | TGA ATG GAT TAT CGT GAC TCT CTC | Exon 2 | 55 | |

| S-2B | TGC CAT TGC TCA GGT ACA TAT TT | Exon 2 | 55 | 445 |

| AS-2B | TCA ACA GCT TTC TAT AGG GAA AAA | Intron 2 | 55 | |

| Primers used for PCR, SSCP, and direct sequencing of exons 2 to 6 | ||||

| S-21 | GTGTTTTTGTTTCTGAGCTGAGAT | Intron 1 | 60 | 251 |

| AS-22 | CGCCTCCCATATTTGGGTAG | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-23 | AGAACCCGTACCCATAATATATG | Exon 2 | 60 | 311 |

| AS-11 | GAAAAAGAACTATGTGAATGGAT | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-24 | GCTCAGGTACATATTTGTTCGGG | Exon 2 | 60 | 269 |

| AS-25 | TTTCAGGATTCAGTGCTGCTC | Exon 2 | 60 | |

| S-26 | TGTGATACAAACCACATCATTTG | Exon 2 | 60 | 274 |

| AS-13 | GCCAAACAATCATTATATACAAG | Intron 2 | 60 | |

| S-17* | TGGATTCTCAGTCGTTCTGGTGA | Intron 2 | 60 | 244 |

| AS-18 | CTTCTCCCTCAAGACAACATGAA | Intron 3 | 60 | |

| S-5 | TCACTCCTTTCTTCCCCTCTC | Intron 3 | 58 | 267 |

| AS-14 | AATCCCAACCATGAATGCCCTC | Intron 4 | 58 | |

| S-15 | TCTTCCTGAGGTATGATTATGGTG | Intron 4 | 57 | 298 |

| AS-16 | AAGAGTTCAGACACAATCTTTTCTC | Intron 5 | 57 | |

| S-19* | GGTCATTGTTATCATGGGACAG | Intron 5 | 58 | 361 |

| AS-20 | TCTTACAATCTAGGCTTCCTTC | Intron 6 | 58 | |

| Primers used for RT-PCR of PIG-A fragments for SSCP | ||||

| S-35 | CTC TAA GAA CTG ATG TCT AAA CCG | NA | NA | 176 |

| As-22 | C GCC TCC CAT ATT TGG GTA G | NA | NA | |

| S-23 | AGA ACC CGT ACC CAT AAT ATA TG | NA | NA | 311 |

| As-11 | GAA AAA GAA CTA TGT GAA TGG AT | NA | NA | |

| S-24 | GCT CAG GTA CAT ATT TGT TCG GG | NA | NA | 269 |

| As-25 | TTT CAG GAT TCA GTG CTG CTC | NA | NA | |

| S-26 | TGT GAT ACA AAC CAC ATC ATT TG | NA | NA | 242 |

| As-36 | TCT GGA TAT TTC TGA CAG AGT TCA G | NA | NA | |

| S-38 | ATT GTT GTT GTC AGC AGA CTT G | NA | NA | 333 |

| AsPIG-Ae | CTC AGG AAT TCC ACC AAC TCT | NA | NA | |

| S-40 | GCA TGG CGA TCG TGG AAG CAG | NA | NA | 293 |

| As-41 | TCG TTT GTC CAT TGG CAA CAC AGC | NA | NA | |

| S-30 | CTG AAG TCA GGG ACA TTG CC | NA | NA | 381 |

| As-20 | TCT TAC AAT CTA GGC TTC CTT C | NA | NA | |

| Primers for 1st and 2nd round mutation-specific PCR | ||||

| SD-1 | GTA AGG AAA ATA CTA AG | Exon 2 | 48 | 188 |

| ASD-1 | AGT CTA CAA TGC AAT TA | Intron 2 | 48 | |

| SD-2 | GTA AGG AAA ATA CTA AG | Exon 2 | 48 | 168 |

| ASD-2 | CTA TCA TTT CAT TAC CT | Intron 2 | 48 |

Primers S17 and S19 are derived from Iida et al.17

NA indicates not applicable.

Genomic DNA (100 ng) was used in a reaction containing 1 × manufacturer's buffer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP), 15 pmol each of sense and antisense primer, and 1U Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) in a total volume of 50 μL. Amplification was carried out for 35 cycles of 40 seconds at 95°C, 1 minute at 55°C, and 1 minute 30 seconds at 75°C, with a final extension for 10 minutes at 75°C. In some experiments these fragments were used for preliminary heteroduplex analysis, but the size of the larger fragments did not allow successful single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide. The products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), cloned into pCR2.1 vector by blunt-end cloning using the ZeroBlunt-Kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and transformed into TOP10F′ One Shot cells (Invitrogen). Transformed cells were seeded onto Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and grown overnight. A reaction mix was made up to 57 μL final volume containing 500 nM of reverse M13 primer and T7 primer, 50 mM KCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, and 200 μM of each dNTP. A minimum of 10 colonies were picked from each plate and boiled in the reaction mixture for 15 minutes at 95°C. Then 0.3 U Taq DNA polymerase was added and amplification was performed for 35 cycles of 1 minute at 96°C, 1 minute at 55°C, 1 minute 30 seconds at 73°C, and a final extension time of 10 minutes at 73°C.

The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide. Products of the expected length were purified for nucleotide sequencing using the QIAquick purification kit.

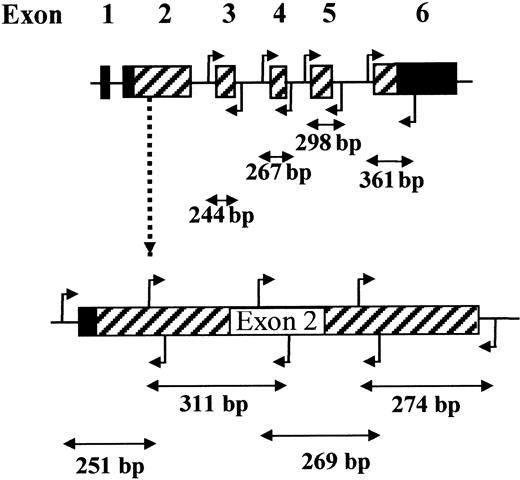

PCR for SSCP and direct sequencing

In some experiments, PCR fragments were digested with restriction enzymes to obtain optimum size bands for SSCP, as described.18 As an alternative, we designed primers to amplify the entire coding regions of the PIG-A gene in 8 overlapping fragments of suitable size for PCR and SSCP without further digestion (Figure 1; Table 2, “Primers used for PCR, SSCP, and direct sequencing of exons 2 to 6”). These primers amplify the exons and 5′ and 3′ intron/exon boundaries, but the extent of intron sequences was minimized to reduce the size of the fragments and to avoid irrelevant positive results due to intron polymorphisms. Because of its size, exon 2 was amplified in 4 overlapping fragments with appropriate primer pairs. For PCR, 100 ng genomic DNA was used in a reaction containing 1 × standard buffer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), 100 μM each dNTP, 15 pmol each of sense and antisense primer, and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold; Applied Biosystems), in a total volume of 50 μL. Amplification was carried out for 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 57° to 60°C (as specified for each exon in Table 2, “Primers used for PCR, SSCP, and direct sequencing of exons 2 to 6”), and 1 minute at 72°C, preceded by 1 cycle of 12 minutes at 95°C to activate the polymerase and followed by 1 cycle of 5 minutes at 72°C.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

A maximum 2 μg total cellular RNA from either granulocytes or lymphocytes was heated to 70°C for 3 minutes and then chilled on ice. The RNA was made up to a total volume of 20.2 μL containing 0.4 μg random primers (Promega), 1 × manufacturer's First Strand Buffer, 25 U RNasin, and 250 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Gibco Life Sciences). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes followed by 42°C for 1 hour. cDNA (2 μL) was used to amplify the entire coding region of the PIG-A gene using different sets of primers as is shown in Table 2 (“Primers used for RT-PCR ofPIG-A fragments for SSCP”). PCR conditions were as stated above.

Single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP)

Formamide loading buffer (10 μL; 95% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 0.25% bromophenol blue and 0.25% xylene cyanol) was added to 3 to 5 μL PCR products. Samples were denatured by incubation at 95°C for 2 to 3 minutes and transferred immediately onto an ice slurry. Of each sample, 5 μL was loaded onto a 1 × mutation detection-enhanced (MDE) (FMC BioProducts, Wokingham, United Kingdom) polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed at 300 V for 17 to 24 hours under conditions optimized for each fragment.

Heteroduplex analysis (HA)

Equivalent quantities of PCR-amplified wild-type and mutant DNA were mixed, except for samples from female patients, which contain normal sequences derived from the inactive X-chromosome, and from males who had more than 30% normal cells in the sample. Of each DNA mixture, 5 μL was heat denatured at 95°C for 2 to 3 minutes, then allowed to slowly cool to room temperature for 1 hour for duplex formation. Immediately before loading, 2 μL of 30% glycerol loading buffer was added to each sample. Samples were electrophoresed at 250 V at 4°C for 12 hours or longer.

Silver staining

Acrylamide gels were fixed in 10% ethanol 0.5% acetic acid. For staining, gels were incubated for 15 minutes in 0.1% silver nitrate, rinsed with water, and then developed for 20 minutes in 0.15% formaldehyde 1.5% NaOH and fixed for 10 minutes in 0.75% sodium carbonate.

Isolation and purification of DNA fragments from agarose or silver-stained polyacrylamide gels

Bands were excised from the gel, and incubated with 4 to 6 V QX1 buffer (Qiagen) at 65°C for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing. DNA was isolated on QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen) and eluted in 30 μL 10 mM Tris 1 mM EDTA. The eluted DNA (2 μL) was used for reamplification.

Mutation-specific PCR

DNA containing the 5 nucleotide (nt) deletion at nucleotides 662 to 666 was specifically amplified by seminested PCR. In the first round, DNA was amplified with the mutation-specific primer muk/s and antisense primer muk/as (Table 2, “Primers used for RT-PCR of PIG-A fragments for SSCP”) for 35 cycles consisting of 95°C for 40 seconds, 48°C for 1 minute, 75°C for 1 minute 30 seconds, with a final extension of 10 minutes at 75°C. The first-round product (1 μL) was then reamplified with the mutation-specific primer muk/s and antisense primer muk/2as for an additional 35 cycles. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide. Products of the expected length were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit and the nucleotide sequence was determined.

DNA sequencing

Sequencing was carried out either manually using a Thermo Sequenase 33P radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences), or by fluorescent sequencing using an ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit using fragment-specific primers; fragments were analyzed using an automated sequencer ABI PRISM model 310 (Applied Biosystems). Abnormal sequences were confirmed by analysis of the opposite strand. All mutations were confirmed by reanalysis of the original patient material.

Results

Quantitation of the expression of GPI-linked surface proteins

Granulocytes and lymphocytes were separated from the peripheral blood of AA patients, and the expression of GPI-anchored proteins on granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence and flow cytometry. Results are summarized in Table3.

Percentages of cells negative for GPI-anchored proteins

| Patient no. . | Neutrophils . | Monocytes . | Lymphocytes . | RBCs . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %CD59− . | %CD66b− . | %CD55− . | %CD59− . | %CD55− . | %CD59− . | |

| 1 | 72.9 | 71.1 | 16.9 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 74.9 | 71.0 | 66.5 | 42.3 | 35.8 | 0.3 |

| 3 | NA | 31.7 | 37.3 | 34.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 4 | NA | 65.8 | NA | NA | 60.9 | NA |

| 5 | 92.9 | 57.7 | 48.9 | 13.6 | 9.5 | 3.4 |

| 6 | 15.4 | 22.4 | 8.1 | 13.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| 7 | 12.4 | 5.3 | NA | 14.2 | 11.8 | 0.2 |

| 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.1 | 21.9 |

| 9 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 23.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 2.1 |

| 10 | 6.7 | 13.1 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| 11 | 10.4 | NA | 48.1 | 7.0 | 19.4 | 18.4 |

| 12 | 46.5 | 48.6 | NA | 3.0 | NA | 2.4 |

| 13 | 13.3 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 0.3 |

| 14 | 80.2 | 69.3 | 16.8 | 14.5 | 27.5 | 17.1 |

| 15 | 19.8 | 20.9 | 15.1 | 4.5 | 40.2 | 9.6 |

| 16 | 32.6 | 28.2 | 29.4 | 10.5 | 3.1 | 1.2 |

| 17 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 2.9 |

| 18 | 9.1 | 7.2 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

| 19 | 72.1 | 68.6 | 58.2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 20 | 50 | 57 | 54 | 5 | 59 | 53 |

| 21 | 16 | 18 | 99 | 3 | 9 | 18 |

| 22 | 59 | 30 | 73 | 3 | 9 | 78 |

| 23 | 69 | 85 | 53 | 11 | 9 | 41 |

| 24 | 87 | 85 | 39 | 17 | 42 | 44 |

| 25 | 17 | 17 | 83 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| 26 | 90 | 90 | NA | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| 27 | 61 | 65 | 31 | 6 | 19 | 0 |

| 28 | 54 | 62 | 60 | 14 | 4 | 4 |

| 29 | 24 | 71 | 84 | 10 | 42 | 4 |

| 30 | 75 | 88 | NA | 0 | 16 | 12 |

| 31 | 74 | 85 | 42 | 4 | 35 | 28 |

| 32 | 18 | 17 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | 51 | 51 | 60 | 0 | 20 | 3 |

| 34 | 84 | 94 | 27 | 7 | 45 | 20 |

| 35 | 16 | 17 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 36 | 23 | 25 | 77 | 4 | 14 | 21 |

| 37 | 32 | 38 | 72 | 7 | 13 | 8 |

| 38 | 11 | 20 | 87 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 39 | 62 | 50 | 61 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 40 | 65 | 61 | 60 | 9 | 13 | 51 |

| Patient no. . | Neutrophils . | Monocytes . | Lymphocytes . | RBCs . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %CD59− . | %CD66b− . | %CD55− . | %CD59− . | %CD55− . | %CD59− . | |

| 1 | 72.9 | 71.1 | 16.9 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 74.9 | 71.0 | 66.5 | 42.3 | 35.8 | 0.3 |

| 3 | NA | 31.7 | 37.3 | 34.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 4 | NA | 65.8 | NA | NA | 60.9 | NA |

| 5 | 92.9 | 57.7 | 48.9 | 13.6 | 9.5 | 3.4 |

| 6 | 15.4 | 22.4 | 8.1 | 13.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| 7 | 12.4 | 5.3 | NA | 14.2 | 11.8 | 0.2 |

| 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.1 | 21.9 |

| 9 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 23.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 2.1 |

| 10 | 6.7 | 13.1 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| 11 | 10.4 | NA | 48.1 | 7.0 | 19.4 | 18.4 |

| 12 | 46.5 | 48.6 | NA | 3.0 | NA | 2.4 |

| 13 | 13.3 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 0.3 |

| 14 | 80.2 | 69.3 | 16.8 | 14.5 | 27.5 | 17.1 |

| 15 | 19.8 | 20.9 | 15.1 | 4.5 | 40.2 | 9.6 |

| 16 | 32.6 | 28.2 | 29.4 | 10.5 | 3.1 | 1.2 |

| 17 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 2.9 |

| 18 | 9.1 | 7.2 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

| 19 | 72.1 | 68.6 | 58.2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 20 | 50 | 57 | 54 | 5 | 59 | 53 |

| 21 | 16 | 18 | 99 | 3 | 9 | 18 |

| 22 | 59 | 30 | 73 | 3 | 9 | 78 |

| 23 | 69 | 85 | 53 | 11 | 9 | 41 |

| 24 | 87 | 85 | 39 | 17 | 42 | 44 |

| 25 | 17 | 17 | 83 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| 26 | 90 | 90 | NA | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| 27 | 61 | 65 | 31 | 6 | 19 | 0 |

| 28 | 54 | 62 | 60 | 14 | 4 | 4 |

| 29 | 24 | 71 | 84 | 10 | 42 | 4 |

| 30 | 75 | 88 | NA | 0 | 16 | 12 |

| 31 | 74 | 85 | 42 | 4 | 35 | 28 |

| 32 | 18 | 17 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | 51 | 51 | 60 | 0 | 20 | 3 |

| 34 | 84 | 94 | 27 | 7 | 45 | 20 |

| 35 | 16 | 17 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 36 | 23 | 25 | 77 | 4 | 14 | 21 |

| 37 | 32 | 38 | 72 | 7 | 13 | 8 |

| 38 | 11 | 20 | 87 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 39 | 62 | 50 | 61 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 40 | 65 | 61 | 60 | 9 | 13 | 51 |

NA indicates not available.

The size of the PNH clone varied greatly among patients and among cell types. In all cases, the deficient cells were detectable in neutrophils, but in a number of cases deficient cells were undetectable in RBCs. In most patients, lymphocytes had at most a small degree of CD59 deficiency.

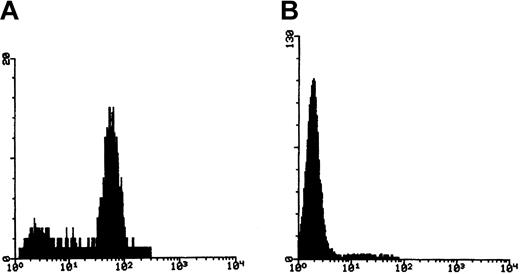

Immunomagnetic enrichment of minor PNH clones

In order to avoid biasing our results toward mutations associated with only major PNH clones, granulocytes from patients with only a small percentage of GPI-negative cells were enriched by immunomagnetic depletion of CD59+ cells. Enriched cells were relabeled with CD59 and rabbit antimouse FITC (RAM-FITC) for flow cytometric evaluation. More than 90% purity was obtained in most cases (Figure 2).

Enrichment of CD59− granulocytes with immunomagnetic beads.

(A) Fluorescence histogram of CD59 staining of granulocytes before separation, showing a minor negative population. (B) Fluorescence histogram after depletion of CD59+ cells.

Enrichment of CD59− granulocytes with immunomagnetic beads.

(A) Fluorescence histogram of CD59 staining of granulocytes before separation, showing a minor negative population. (B) Fluorescence histogram after depletion of CD59+ cells.

Detection of PIG-A mutations

The PIG-A exon 2 coding sequences of DNA from affected granulocytes of 11 patients (nos. 1-11) were amplified in a series of overlapping fragments using the primers described in Table 2(“Primers used for cloning and sequencing of exon 2”). PCR products were subcloned into the vector pCR2.1. Lysates of individual colonies were reamplified by PCR and the sequence determined. In 19 patients, 24 mutations were detected. One is probably a constitutive polymorphism, as it does not give rise to any change in the protein sequence. Results of the mutation analyses are summarized in Table4.

Details of PIG-A gene mutations

| Patient no. . | Exon . | Codon . | Position . | Mutation . | Consequence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 58 | 257 | C>T | STOP |

| 2 | 2 | 113 | 423 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 3 | 2 | 168/221 | 588/748 | A>G/A>C | Asn→Ser/Arg→Ser |

| 3 | 2 | 193 | 663 | 64 bp ins | Frameshift |

| 3 | 2 | 176-177 | 612-616 | del GTGAT | Frameshift |

| 4 | 2 | 77 | 316 | del A | Frameshift |

| 5 | 2 | 234-235 | 786-788 | del TTG | del Val |

| 6 | 2 | 235-236 | 788-793 | del GTTTAC>TTT | Val-Tyr→Phe |

| 7 | 2 | 122 | 450-451 | del TC | Frameshift |

| 7 | 2 | 125 | 460 | C>T | Ile→Ile |

| 8 | 2 | 128-131 | 468-476 | del ATAGTTCTT | Frameshift |

| 8 | 2 | 122 | 450-451 | del TC | Frameshift |

| 9 | 2 | 90 | 354 | ins T | Frameshift |

| 10 | 2 | 229 | 770-772 | del GTT | del Val |

| 11 | 2 | 171-176 | 596-613 | del 18 bp | del 6 aa |

| 11 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 12 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 13 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 14 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 15 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 16 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 17 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 18 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 19 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 20 | 2 | 175 | 609-610 | del TT | Frameshift |

| 21 | 2 | 188 | 648 | ins AC | Frameshift |

| 22 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTA CT | Frameshift |

| 23 | 2 | 232 | 781 | ins 88 bp | Stop |

| 24 | 5 | 354 | 1145 | ins 31 bp | Frameshift |

| 24 | 2 | 56 | 252 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 23 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 24 | 2 | 86 | 342 | G>A | Gly→Asp |

| 24 | 2 | 106 | 402 | T>G | Leu→Arg |

| 25 | 6 | 438-439 | 1397-1402 | del TTCCTC | 2 aa del |

| 25 | 2 | 152 | 540 | C>G | Thr→Arg |

| 25 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 26 | 6 | 448-454 | 1428-1447 | del 19 bp | Frameshift |

| 26 | 2 | 92 | 359 | T>G | Leu→Val |

| 27 | 6 | 407 | 1305 | T>A | Stop codon |

| 28 | 6 | 456 | 1451 | G>A | Asp→Asn |

| 28 | 6 | 448 | 1429 | T del | Frameshift |

| 28 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 29 | 6 | 428 | 1368-1369 | TT del | Frameshift |

| 29 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 30 | 2 | 188 | 649 | del T | Frameshift |

| 31 | 2 | 130 | 474 | del C | Frameshift |

| 32 | 2 | 206 | 701 | ins T | Frameshift |

| 32 | 4 | 306 | 1002 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 32 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 33 | 2 | 145-146 | 518-523 | del 6 bp | Met Gly del |

| 34 | 2 | 233 | 776-778 | del GTC | Val del |

| 35 | 5 | 353 | 1142 | A>T | Stop |

| 36 | 2 | Intron 2 | G>A | Splice acceptor | |

| 36 | 5 | 351-355 | 1138-1149 | del 12 bp | Val, Lys, Ser, Leu |

| 37 | 2 | 164 | 577 | del G | Frameshift |

| 38 | 5 | 353 | 1142 | A>T | Stop |

| 39 | 2 | 159 | 562 | del T | Frameshift |

| 40 | 2 | 109-113 | 412-422 | del 11 bp | Frameshift |

| Patient no. . | Exon . | Codon . | Position . | Mutation . | Consequence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 58 | 257 | C>T | STOP |

| 2 | 2 | 113 | 423 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 3 | 2 | 168/221 | 588/748 | A>G/A>C | Asn→Ser/Arg→Ser |

| 3 | 2 | 193 | 663 | 64 bp ins | Frameshift |

| 3 | 2 | 176-177 | 612-616 | del GTGAT | Frameshift |

| 4 | 2 | 77 | 316 | del A | Frameshift |

| 5 | 2 | 234-235 | 786-788 | del TTG | del Val |

| 6 | 2 | 235-236 | 788-793 | del GTTTAC>TTT | Val-Tyr→Phe |

| 7 | 2 | 122 | 450-451 | del TC | Frameshift |

| 7 | 2 | 125 | 460 | C>T | Ile→Ile |

| 8 | 2 | 128-131 | 468-476 | del ATAGTTCTT | Frameshift |

| 8 | 2 | 122 | 450-451 | del TC | Frameshift |

| 9 | 2 | 90 | 354 | ins T | Frameshift |

| 10 | 2 | 229 | 770-772 | del GTT | del Val |

| 11 | 2 | 171-176 | 596-613 | del 18 bp | del 6 aa |

| 11 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 12 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 13 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 14 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 15 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 16 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 17 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 18 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 19 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 20 | 2 | 175 | 609-610 | del TT | Frameshift |

| 21 | 2 | 188 | 648 | ins AC | Frameshift |

| 22 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTA CT | Frameshift |

| 23 | 2 | 232 | 781 | ins 88 bp | Stop |

| 24 | 5 | 354 | 1145 | ins 31 bp | Frameshift |

| 24 | 2 | 56 | 252 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 23 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 24 | 2 | 86 | 342 | G>A | Gly→Asp |

| 24 | 2 | 106 | 402 | T>G | Leu→Arg |

| 25 | 6 | 438-439 | 1397-1402 | del TTCCTC | 2 aa del |

| 25 | 2 | 152 | 540 | C>G | Thr→Arg |

| 25 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 26 | 6 | 448-454 | 1428-1447 | del 19 bp | Frameshift |

| 26 | 2 | 92 | 359 | T>G | Leu→Val |

| 27 | 6 | 407 | 1305 | T>A | Stop codon |

| 28 | 6 | 456 | 1451 | G>A | Asp→Asn |

| 28 | 6 | 448 | 1429 | T del | Frameshift |

| 28 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 29 | 6 | 428 | 1368-1369 | TT del | Frameshift |

| 29 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 30 | 2 | 188 | 649 | del T | Frameshift |

| 31 | 2 | 130 | 474 | del C | Frameshift |

| 32 | 2 | 206 | 701 | ins T | Frameshift |

| 32 | 4 | 306 | 1002 | T>C | Leu→Pro |

| 32 | 2 | 193-194 | 662-666 | del GTACT | Frameshift |

| 33 | 2 | 145-146 | 518-523 | del 6 bp | Met Gly del |

| 34 | 2 | 233 | 776-778 | del GTC | Val del |

| 35 | 5 | 353 | 1142 | A>T | Stop |

| 36 | 2 | Intron 2 | G>A | Splice acceptor | |

| 36 | 5 | 351-355 | 1138-1149 | del 12 bp | Val, Lys, Ser, Leu |

| 37 | 2 | 164 | 577 | del G | Frameshift |

| 38 | 5 | 353 | 1142 | A>T | Stop |

| 39 | 2 | 159 | 562 | del T | Frameshift |

| 40 | 2 | 109-113 | 412-422 | del 11 bp | Frameshift |

del indicates deletion; ins, insertion.

As an alternative strategy, samples nos. 20 to 40 were analyzed by SSCP or HA and direct sequencing without subcloning. The primers shown in Table 2 (“Primers used for PCR, SSCP, and direct sequencing of exons 2 to 6”) were designed to amplify fragments of optimal size for SSCP, without requiring restriction enzyme digestion. The extent of intron sequences in the PCR product was minimized to allow identification of splice site mutations, but to minimize fragment sizes and to avoid positive bands due to intron polymorphisms.

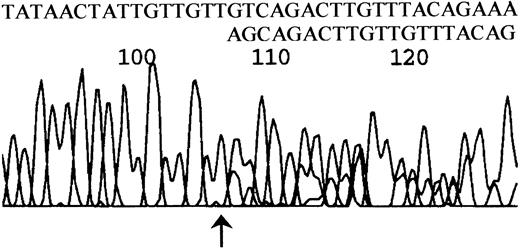

Abnormal SSCP bands were extracted from the gel and reamplified. The purity of the abnormal bands was examined on an SSCP gel, and the DNA was then used for direct sequencing. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing the complementary strand. When the abnormal band could not be separated by SSCP, either the unseparated PCR product or a purified heteroduplex band was used for direct sequencing. This frequently resulted in ambiguous overlapping of normal and mutant sequences. However, frameshifts could be clearly interpreted by examination of the sequence at the point of divergence where unambiguous sequence gave way to overlapping sequence, and single base substitutions could be clearly read in many, but not all, cases. An example of sequence derived from a heteroduplex band is shown in Figure 3. All mutations were confirmed by reamplification and sequencing to exclude the possibility that mutations were introduced during the PCR reaction. By these techniques 33 sequence variations, 3 of which proved to be constitutional polymorphisms, were localized in 21 patients.

DNA sequence derived from a heteroduplex fragment.

A heteroduplex band from patient no. 34 was isolated, reamplified, and sequenced. Note unambiguous sequence up to the arrowed nucleotide (T at nt 775 on the PIG-A cDNA sequence), then ambiguous sequence. By subtracting the normal sequence 775-GTCAGCAGACTTGTT from the observed sequence the alternative peaks can be clearly read as 778-AGCAGACTTGTTAC showing deletion of 3 nucleotides.

DNA sequence derived from a heteroduplex fragment.

A heteroduplex band from patient no. 34 was isolated, reamplified, and sequenced. Note unambiguous sequence up to the arrowed nucleotide (T at nt 775 on the PIG-A cDNA sequence), then ambiguous sequence. By subtracting the normal sequence 775-GTCAGCAGACTTGTT from the observed sequence the alternative peaks can be clearly read as 778-AGCAGACTTGTTAC showing deletion of 3 nucleotides.

Large insertions and deletions in 4 patients

PCR products from 21 patients were examined by high-resolution electrophoresis on 4% NuSeive agarose gels (FMC BioProducts). Minor abnormal bands were observed, and in some cases these were identified as heteroduplex bands. Electrophoresis of products from patients nos. 23, 24, and 26 showed extra abnormal bands in exons 2, 5, and 6, respectively, in addition to the normal-sized band for that particular DNA fragment, suggesting the presence of insertions or deletions. We were concerned as to whether these minor bands might be PCR artefacts. Repeat of PCR using fresh DNA again showed the same bands, and restriction analysis confirmed that these abnormal bands were related to the expected PCR product (data not shown). RNA from granulocytes or lymphocytes of these patients was subjected to RT-PCR, and in each case the presence of the abnormal band was confirmed. Abnormal bands were excised from the gels and were used for direct sequencing after reamplification.

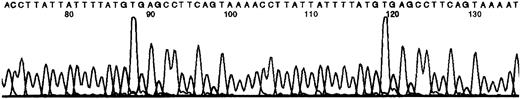

Sequencing results for female patient no. 23 showed an 88-bp insertion starting at nt 781, as previously reported.19 This insertion was a direct tandem repeat of the PIG-A gene sequence and resulted in a frameshift producing a premature stop codon (TAA) 5 codons after the start of the insertion. Nucleotide sequencing for patient no. 24 confirmed a 31-bp insertion/duplication in exon 5 (Figure 4).

DNA sequence showing a 31-nt duplication.

An abnormal band from patient no. 24 was isolated, reamplified, and sequenced. The duplicated sequence is shown overlined.

DNA sequence showing a 31-nt duplication.

An abnormal band from patient no. 24 was isolated, reamplified, and sequenced. The duplicated sequence is shown overlined.

This mutation resulted in a frameshift and created a TGA stop codon 6 codons after the start of the insertion. Patient no. 3, studied by subcloning and sequencing of PCR products, showed a similar 64-bp insertion due to tandem duplication, resulting in a stop codon 5 codons after the start of the insertion. For patient no. 26, sequencing revealed that 19 nt (from nt 1428-1447) were deleted from the abnormal fragment in exon 6, causing a frameshift and a TAG stop codon immediately one codon after the deletion.

A common mutation detected in 15 patients

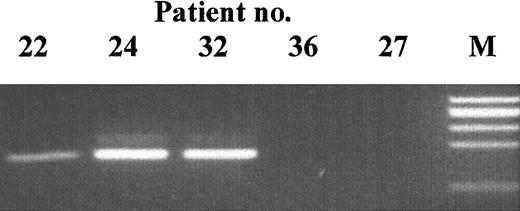

During the above studies we observed the same 5-bp deletion mutation (GTACT at 662-666 in exon 2) in 3 patients (nos. 11, 22, and 24). An identical deletion has already been reported.20 To confirm these mutations, and to analyze whether the same mutation might occur in other patients, we designed PCR primers to specifically amplify the mutant but not the normal sequence (Figure 5).

Mutation-specific PCR products.

Patient DNA was amplified with primers specific for the 5-bp deletion at nt 662 to 666. The identity of the bands at 163 bp was confirmed by DNA sequencing. M indicates size marker.

Mutation-specific PCR products.

Patient DNA was amplified with primers specific for the 5-bp deletion at nt 662 to 666. The identity of the bands at 163 bp was confirmed by DNA sequencing. M indicates size marker.

Screened were 38 patients in 2 different laboratories. A PCR product could be amplified by seminested PCR from 15 patients (including the 3 original probands above), but not from any of 26 healthy controls. Patients nos. 12 to 19 were studied by PCR alone and may carry additional mutations. The identity of the mutant PCR fragments was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Although this mutation was prominent in some patients, in others it is clearly present at a low level and does not account for all of the GPI anchor–negative cells.

Multiple mutations in individual patients

Initial screening by both the cloning and the electrophoretic/SSCP methods identified a number of patients with more than one mutation. The electrophoretic/SSCP methods allow an approximate estimate of the size of a given mutant clone in relation to the percentage of CD59− cells. For instance, in patient no. 24, about 85% of granulocytes were GPI negative, whereas the insertion in exon 5 appeared to represent about 10% of the DNA. Therefore another mutation was expected within the PIG-A gene of this patient. SSCP and HA were carried out for the entire PIG-A coding region, and we were able to identify a 5-bp (GTACT) deletion in exon 2. In patients nos. 23 and 26 there was an equally clear discrepancy between the intensity of the mutant band identified and the overall percentage of GPI anchor–negative cells, implying the existence of another mutation, even though we have not yet managed to localize this. In 2 other patients, nos. 21 and 29, there was evidence for an additional mutation based on the intensity of bands in the HA and SSCP gels, and the presence of overlapping sequence in DNA from cells that had been enriched to more than 95% CD59−.

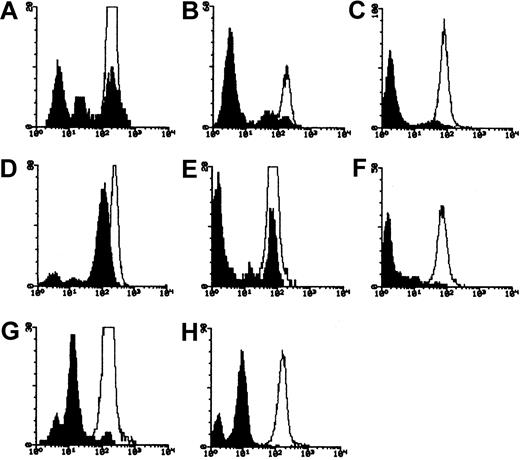

Evidence for 2 clones based on flow cytometry

In 5 of 21 patients, flow cytometric analysis of granulocytes for CD59 revealed 3 peaks: 1 coincident with the healthy control, 1 with the negative control, and 1 representing around 10% of normal CD59 expression (Figure 6). We presume this peak represents the equivalent of the PNH II populations reported in red cells. In 2 cases, nos. 25 and 28, we have identified mutations that may account for the partially positive cells, but in the other 4 patients only null mutations have so far been identified.

PNH Type I, II, and III populations in granulocytes.

Fluorescence histograms of CD59-stained granulocytes from patients (A) no. 22, (B) and (C) no. 23, (D) no. 25, (E) and (F) no. 28, (G) and (H) no. 29, before (A-B,D-E,G) and after (C,F,H) immunomagnetic depletion of CD59+ cells. Unfilled histogram indicates healthy control; filled histogram, patient.

PNH Type I, II, and III populations in granulocytes.

Fluorescence histograms of CD59-stained granulocytes from patients (A) no. 22, (B) and (C) no. 23, (D) no. 25, (E) and (F) no. 28, (G) and (H) no. 29, before (A-B,D-E,G) and after (C,F,H) immunomagnetic depletion of CD59+ cells. Unfilled histogram indicates healthy control; filled histogram, patient.

Discussion

Mutations in the PIG-A gene

PIG-A gene mutation was studied in 40 patients with a history of aplastic anemia. Within the coding sequences of this gene, 43 different somatic mutations were found. Of the mutations, there were 19 different small deletions between 1 to 9 bp, and 3 small insertions between 1 to 2 bp. There were 4 mutations that caused larger deletions of 11 to 19 bp, and 3 others caused larger insertions of 31, 64, and 88 bp. These 3 insertions were each due to tandem duplication of a segment of the PIG-A gene. There were 13 mutations that caused single base pair substitutions: 8 missense, 4 nonsense, and 1 involving a splice junction.

In addition to somatic mutations, a constitutional mutation was found in 2 females and 1 male. The mutation 55C>T (codon 19), which is reported to be a variant polymorphism,13,21 22 does not cause PNH as it was present in normal cells of the same patient (data not shown). We also observed a neutral substitution at position 460 in patient no. 7, which may also be an inherited polymorphism.

In a number of patients we have clear evidence that the mutations found do not represent the whole of the GPI-negative population. In addition, we have a total of 6 patients for whom no mutation has been identified. These patients were extensively screened, although, due to lack of material, all techniques have not been applied to every single patient. It is known that SSCP and HA cannot pick up all mutations, and these results suggest that other sensitive mutation screening techniques need to be considered. Another possibility is that the mutation is not within the PIG-A gene. However, this seems less likely, because the PIG-A gene is X-linked,23 and requires only one mutation in a stem cell to generate the PNH phenotype, whereas other genes involved in GPI-anchor biosynthesis are located on the autosomal chromosomes and 2 mutations would be needed to cause a GPI-anchor deficiency.24 Alternatively, it is possible that some mutations are in noncoding PIG-Asequences, such as promoter mutations or activation of cryptic splice sites in the introns.

Distribution of mutations

In cases where the whole of the coding sequence was screened by SSCP and HA, 19 of 30 mutations were found to be in exon 2. This may not be surprising as this exon encompasses about one half of the whole coding region. One mutation was found for exon 4, 4 for exon 5, and 6 other mutations were localized to exon 6, which has a relatively large coding sequence. Of 20 patients who were screened for exon 2 only, all had at least one mutation in exon 2. At that time we were not deliberately screening for multiple mutations in the same patient. We believe that some of these patients are likely to have mutations in other exons, but the combination of the frequency of exon 2 mutations and the incidence of multiple mutations resulted in all of this series being positive for exon 2.

Mutational hot spots within the PIG-A gene

More than 100 somatic mutations have been reported in thePIG-A gene in different PNH patients. The mutations are distributed throughout the PIG-A sequence, suggesting that they occurred at random sites and that there is no particular mutation hot spot. From 85 different mutations reviewed in Rosse,35 mutations were found twice and 2 were found 3 times. Of our patients, 3 showed a 5-bp GTACT deletion in exon 2 at nt 662 to 666. The same mutation has also been reported in 1 patient20 and we have described the same deletion in 2 patients following immunotherapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.25 This led us to hypothesize that this site might represent a mutational hot spot within the PIG-A gene, and indeed a mutation-specific nested PCR reaction has found this mutation in 15 of 31 patients screened. It should be noted that the deletion is not detectable in the majority of patients by conventional methods, and it may be present in only a minor fraction of the cells.

There are type II and III granulocytes in the circulation

The Ham test can identify 3 distinct cell populations of RBCs with different sensitivities to complement-mediated lysis. PNH type I RBCs have normal expression of GPI-linked proteins, whereas PNH II (intermediate) cells have a partial and PNH III cells have a complete deficiency of GPI-linked proteins.26-28 In many cases, PNH types II and III erythrocytes coexist in the blood cells of the same patient. It is likely that each type of abnormal RBC is caused by a different somatic mutation in the PIG-A gene,29although gain of GPI-anchored proteins from positive cells30,31 and selective loss of GPI-anchored proteins during RBC maturation32 cannot be excluded.

There have been occasional reports on different types of deficient granulocytes. In this study, for 5 of 15 patients we have observed 3 different populations of granulocytes by flow cytometry: 1 population showing normal expression of CD59 (type I), 1 population showing a weak expression (type II), and another population having completely deficient cells (type III). These results correlated with the existence of a type II population in RBCs of the same patients analyzed by flow cytometry. For 2 patients, nos. 25 and 28, who showed type II and type III populations in granulocytes and erythrocytes, base substitution mutations were found in addition to null mutations (Table 4). The null mutations are clearly responsible for the type III populations. We suggest that the base substitutions may account for the type II populations, but further experiments are needed to confirm this.

Most patients have more than one mutation

There are a number of reports of PNH patients with more than one mutation within the PIG-A gene.21,33,34 A recent paper35 has shown that PIG-A mutations can be detected in healthy individuals, albeit at an extremely low level. These results support the hypothesis that a PNH clone has a growth or proliferative advantage over the normal clone in the background of aplasia. In 11 of our patients, more than one mutation was identified. We presume that they have originated from 2 different clones, but we have not formally proved this, except where both mutations are covered by the same PCR fragment.

The electrophoretic methods of analysis allow us to estimate the proportion of a mutation in the total DNA. In 5 patients, the mutation found clearly did not account for the size of the CD59−population. For instance in one patient, no. 26, a 19-bp deletion was detected in a small proportion of granulocytes. Since more than 90% of his granulocytes were CD59 deficient another mutation is expected to be present. In 7 patients, we observed both a CD59− and a CD59lo cell population, but in 4 of these we have identified only null mutations, implying the existence of further mutations. Considering only the patients who have been analyzed by all of these methods, we have clear evidence for more than one mutation in 14 of 18 cases.

Advantages and disadvantages of mutation detection methods

A number of approaches have been used in the past for identifyingPIG-A mutations, including the generation of transformed B-cell and T-cell lines to purify the mutant clone, SSCP to localize mutations, and/or generation and sequencing of multiple plasmid clones. We have identified many of our mutations by direct cloning and sequencing of PCR products, without preliminary localization of the mutations. Given the increasing efficiency and decreasing cost of automated sequencing, this is an effective method for identifying the major mutation in a sample. Since mutations can be introduced into the DNA during PCR, results need to be confirmed by sequencing multiple clones from the same patient, although the problem can be minimized by the use of a proofreading polymerase. Although we have identified more than one mutation in some cases, a potential drawback of this approach is that minor mutations may be missed.

Electrophoretic methods including HA and SSCP may still pick up mutations even when they are present in a small proportion of cells. We designed primer pairs for the efficient amplification ofPIG-A coding sequence from cellular DNA and RNA, with amplified fragments of an appropriate size for efficient SSCP and HA without requiring restriction enzyme digestion. Use of intron-derived primers allows detection of mutations in the splice junctions, but intron sequences were minimized to avoid false-positive SSCP/HA results due to intron polymorphisms. Using exonic primers, 2 of the fragments from exon 2 were amplified. In theory these primers could also amplify sequences from the pseudogene, but we have never observed this in practice. When a minor abnormal band was observed in the silver-stained gels, it was excised, purified, and reamplified. Original PCR products and purified mutant fragments were analyzed by direct sequencing of the PCR product without subcloning. PCR may introduce mutations into a significant proportion of amplified molecules, and these are revealed after subcloning. However, unless amplification is initiated from a single cell, each individual mutation is present in only a minute proportion of the PCR product molecules, and is therefore not seen by direct sequencing.

The strategy of enriching the CD59− cells, followed by PCR, electrophoretic analysis, and direct sequencing of PCR products, has proved very effective in identifying multiple and minor mutations, and in demonstrating in particular cases that there must be more than one clone present, even when the additional mutations have not been identified. Using other strategies, it is very easy to assume that the first mutation detected is the only mutation in that patient, and therefore easy to miss the presence of additional mutations.

Comparison of the mutations found in primary PNH and AA/PNH

Most of the mutations observed in PNH patients have been small deletions (1-14 bp), small insertions (1-8 bp), and base substitutions (see Rosse3 for a recent review). Several studies have included patients with AA/PNH13,14,21,36,37 and found similar mutations to those in primary PNH. In our study, most of the mutations were similar to those previously described, but 3 distinct classes of mutations were also identified. We observed 3 insertions, of 31, 64, and 88 bp. Before we described one of these mutations, published as a case report in 1997,19 no similar mutations had been described. Since then, 4 examples have been reported, with insertions of 34,38 31, 25,39and 19 bp.40 Interestingly, like all 3 of our mutations, these insertions were all due to tandem duplications. Of these 7 mutations, 2 were found in hemolytic AA patients, so they do not appear to be specific to AA/PNH. Our 4 deletions, of 11, 12, 18, and 19 bp, also seem to differ from most previous publications, but 2 similar deletions have been reported by Nafa et al41and 3 others elsewhere. We suspect that the failure to find such insertions and deletions in the majority of studies is related to the particular techniques used. The 5-bp deletion that we have observed in a high proportion of our patients has again been previously reported, but only in a single PNH patient.20

A major difference in the mutational spectrum we have observed is the incidence of multiple mutations in a majority of patients. Although patients with up to 4 different mutations have been previously reported,15,42 multiple mutations have been reported in less than 20% overall of cases of PNH. Our results raise the question of whether this is specific to AA/PNH as opposed to de novo hemolytic PNH. The mutations in question are null mutations, and are not therefore subject to differential selection. It is possible that we may be observing a different mutational process in AA/PNH with a possibly increased mutation rate.43 44 In order to examine these hypotheses, it is necessary to reinvestigate the mutational spectrum in de novo PNH to determine whether the preponderance of multiple mutations we have observed is indeed unique to AA/PNH.

Principal Investigators for the BIOMED II Pathophysiology and Treatment of Aplastic Anaemia Study Group were Andrea Bacigalupo, Ospedale San Martino, Divisione Ematologia II, Genova, Italy; Ben Bradley and Jill Hows, University of Bristol, Department of Transplantation Sciences, Bristol, United Kingdom; and H. Schrezenmeier, Institute for Clinical Transfusion Medicine and Immungenetics, Department of Transfusion Medicine, University of Ulm, Germany.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 7, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2095.

Supported by grants from the European Community (BIOMED II Project no. BMH4-CT96-1031) (H.S.) and from the United Kingdom Leukaemia Research Fund (T.R.R.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Tim Rutherford, Department of Haematology, St George's Hospital Medical School, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, United Kingdom; e-mail: trutherf@sghms.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal