A retrospective survey of patients with pathologically reviewed extragastric mucosa-associated lymphoma tissue (MALT) lymphomas from 20 institutions was performed. A total of 180 patients with histologically confirmed diagnosis of extragastric MALT lymphomas were studied. Their median age was 59 years (range, 21-92 years). Ann Arbor stage I disease was present in 115 patients (64%) and stage II disease in 16 (9%). Most cases were in the low or low-intermediate risk groups according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI). Forty-one (23%) patients had involvement of more than one extranodal site at diagnosis and in 24 cases (13%) the lymphoma presented at multiple mucosal sites (9 of them with only mucosal involvement, without bone marrow or nodal disease). Lymph node involvement was present in 21%. Patients were treated with a variety of therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy in 78 cases. The median overall survival (OS) was not reached; the 5-year OS rate was 90% (95% CI, 82%-94%), the 5-year cause-specific survival (CSS) was 94% (95% CI, 87%-97%), and the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 60% (95% CI, 50%-70%). Multivariate analysis showed that Ann Arbor stage was significantly associated with longer OS, nodal involvement with longer CSS, and favorable IPI score with better PFS. At a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 48 patients (27%; 95% CI, 20%-34%) had a relapse, 6 (3%; 95% CI, 1%-7%) showed histologic transformation, and 18 (10%; 95% CI, 6%-15%) experienced the development of a second tumor. Our data confirm the indolent nature of nongastric MALT lymphomas and the high rate of patients presenting with disseminated disease, which, when limited to mucosal sites, was not associated with a poorer outcome.

Introduction

The group of lymphomas previously classified as low-grade MALT lymphomas includes a number of extranodal B-cell neoplasms defined as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) in the Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL)1 and in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.2

Far from being rare, MALT lymphomas account for approximately 7% to 8% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), being the third most frequent histologic subtype (after diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma).2,3 The stomach is the most common and best-studied site of involvement.4 MALT lymphomas have also been described in various nongastrointestinal sites, such as salivary gland, thyroid, skin, conjunctiva, orbit, larynx, lung, breast, kidney, liver, prostate, and even in the intracranial dura.5-20 Involvement of multiple mucosal sites is often present and disseminated disease appears to be more common in nongastrointestinal MALT lymphomas, in which one fourth of cases has been reported to present with involvement of multiple mucosal sites or nonmucosal sites such as bone marrow.8,9,21,22 It has been postulated that this dissemination may be due to the specific expression of special homing receptors or adhesion molecules on the surface of the B cells of MALT.23-25 Nongastric MALT lymphomas have been difficult to characterize because these tumors, numerous when considered together, are distributed so widely throughout the body that it is difficult to assemble adequate series of any given site. The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) conducted an analysis of a large series of patients who were diagnosed as having nongastric MALT lymphomas with the aim of better characterizing this disease entity.

Patients and methods

We considered eligible for the study the patients with an initial diagnosis of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) according to the REAL/WHO classification criteria and presenting with a clinically dominant nongastric site of localization. The primary site of lymphoma involvement was operationally defined as the clinically dominant extranodal component, which requires diagnostic investigation and to which primary treatment must often be directed.

Standardized forms were submitted to participating institutions to obtain data on age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), disease stage defined according to the Ann Arbor criteria,26 location of extranodal disease, presence of B symptoms, serum lactate dehydrogenases (LDH) and β2-microglobulin levels, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection serology, and association with previous autoimmune disease. The distribution among the International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk groups was defined according to the published criteria.27 Due to the retrospective nature of the study, not all variables were available for each patient. We also obtained data on initial treatment, response to treatment, failure, histologic transformation to a high-grade lymphoma, development of a second tumor, cause of death, and disease status at last follow-up.

All cases were reviewed by a panel of pathologists to confirm the diagnosis and to stratify them according to the percentage of large cells (< 10% versus > 10%). Immunophenotyping was performed whenever required to exclude other small lymphocytic neoplasms. The presence of solid clusters (> 20 cells) or sheetlike proliferations of large cells was considered to indicate transformation into a diffuse large cell lymphoma and was an exclusion criteria. A preliminary analysis of this series has been already presented,28,29including 66 additional patients from a series that underwent separate histology evaluation and had already been published elsewhere.9 In the present analysis, only the cases reviewed by the IELSG pathology panel were included. The databases of the 20 participating centers included 365 eligible patients whose lymphoma diagnosis was made from 1983 to 1999. Adequate pathologic material for histologic revision was available in 243 cases: 52 patients were ineligible on review (20 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with accompanying MALT lymphoma component, 9 with reactive lymphoid proliferation, 9 with mantle cell lymphoma, 8 with follicular lymphoma, 3 with plasmacytoma, 2 with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and 1 with lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma). Of the remaining 191 cases, 2 patients were excluded from the study because of a primary gastric localization and 9 because of incomplete or inadequate follow-up data.

The staging procedures were not standardized but varied depending on different centers and periods and included chest and abdomen imaging investigations (computed tomography [CT] or ultrasound [US] scans), digestive tract endoscopic investigations, and bone marrow biopsy.

All evaluations of clinical stage and response to treatment were based on the original data recorded by local physicians. Complete remission (CR) was defined as the disappearance, for at least 1 month, of all clinical evidence of the disease, including the normalization of all laboratory values and radiographs that were abnormal at presentation including a normalization of bone marrow, if initially involved. A CR to the initial treatment was assigned when patients with stage I disease had no evidence of disease after diagnostic surgical excision with or without subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. Partial remission (PR) was defined as a more than 50% reduction in the largest dimension of involved sites. Stable disease (SD) was defined as a less than 50% regression or less than 50% increase of the known sites of disease. Relapsing or progressive disease (PD) was defined as appearance of any new lesion or increase of at least 50% in the size of the previously involved sites. Statistical analysis was conducted using the STATA 5.0 software package (Computing Resource Centre, Santa Monica, CA). According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) criteria,30 overall survival (OS) was calculated from time of diagnosis to time of death from any cause or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from time of diagnosis to the time of primary treatment failure, relapse/progression, or death from lymphoma. Cause-specific survival (CSS) was measured from time of diagnosis to the time of death from disease or treatment-related causes. The median follow-up was computed by the reverse Kaplan-Meier method.31 Survival probabilities were calculated using the life table method and survival curves were estimated by the method of Kaplan-Meier and differences between curves were analyzed using the log-rank test.32 The binomial exact 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for percentages. The χ2 test was used for testing associations in 2-way tables. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis of OS, CSS, and PFS and estimation of relative risk.33

Results

Pathology review

A total of 180 patients with confirmed histologic diagnosis of nongastric MALT lymphoma were included in the analysis. The percentage of large cells (transformed centroblastlike or immunoblastlike cells) was evaluated. Scattered large cells were a common feature, but in the large majority of cases their number was below 10%; only in 19 cases (11%) was a higher large cell rate (10%-20%) present, always without compact clusters or sheets indicating the emergence of a transformed clone. In no case did the rate of large cells exceed 20%.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the main clinical features at presentation. The median age of the 68 men and 112 women was 59 years (range, 21-92 years). Ann Arbor stage I disease was present in 115 patients (64%); 16 (9%) patients had disease involving locoregional nodes to the primary extranodal site of disease (stage II), whereas 49 (28%) patients presented with stage IV disease. Forty-one (23%) patients presented more than one extranodal site of disease at diagnosis. More than one MALT site of localization was present in 24 cases (13%) at time of clinical onset (9 of them presenting with only mucosal involvement, without bone marrow or nodal disease). Thirty-eight (21%) patients had a nodal involvement. The rate of multiple MALT site localizations was significantly higher in cases with nodal involvement (29% versus 9%; P = .001). B symptoms were documented in 5 patients, whereas 6 patients had an impaired performance status (ie, ECOG PS score > 1). The LDH serum level was elevated in 37 of the 147 patients who had this measured at presentation, and 23 patients of the 66 tested patients had high levels of serum β2-microglobulin. The IPI was applicable to 177 patients; 146 patients ranked in the low/low-intermediate risk group and 31 patients in the intermediate-high/high risk group. In 21 cases a previous autoimmune disease was reported represented in most cases by a Sjögren syndrome, strongly associated with a localization in the salivary glands (P < .001). Serologic evidence of HCV infection was reported in 18 of the 75 patients in whom the information was available and was significantly associated with a primary localization in the parotid gland (P = .022) and in the lachrymal glands (P = .011). The initial dominant lymphoma localizations are indicated in Table2.

Clinical characteristics of patients

| Features . | No. of patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median | 59 y |

| Range | 21-92 y |

| Sex | |

| Male | 68 (38) |

| Female | 112 (62) |

| Performance status | |

| ECOG score 0-1 | 173 (96) |

| ECOG score 2-4 | 6 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Ann Arbor Stage | |

| I | 115 (64) |

| II | 16 (9) |

| IV | 49 (27) |

| B symptoms | |

| Absent | 175 (97) |

| Present | 5 (3) |

| Serum LDH level | |

| Normal | 110 (61) |

| Elevated | 37 (21) |

| Unknown | 33 (18) |

| Serum β2-microglobulin level | |

| Normal | 43 (24) |

| Elevated | 23 (13) |

| Unknown | 114 (63) |

| Number of extranodal sites | |

| 1 | 139 (77) |

| More than 1 | 41 (23) |

| Nodal involvement | |

| Absent | 142 (79) |

| Present | 38 (21) |

| Percentage of blasts | |

| Less than 10% | 161 (89) |

| 10%-20% | 19 (11) |

| Bone marrow involvement | |

| Absent | 155 (86) |

| Present | 25 (14) |

| Autoimmune background | |

| Absent | 159 (88) |

| Present | 21 (12) |

| IPI | |

| Low to low-intermediate risk | 146 (81) |

| Intermediate/high to high risk | 31 (17) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) |

| Features . | No. of patients (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median | 59 y |

| Range | 21-92 y |

| Sex | |

| Male | 68 (38) |

| Female | 112 (62) |

| Performance status | |

| ECOG score 0-1 | 173 (96) |

| ECOG score 2-4 | 6 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Ann Arbor Stage | |

| I | 115 (64) |

| II | 16 (9) |

| IV | 49 (27) |

| B symptoms | |

| Absent | 175 (97) |

| Present | 5 (3) |

| Serum LDH level | |

| Normal | 110 (61) |

| Elevated | 37 (21) |

| Unknown | 33 (18) |

| Serum β2-microglobulin level | |

| Normal | 43 (24) |

| Elevated | 23 (13) |

| Unknown | 114 (63) |

| Number of extranodal sites | |

| 1 | 139 (77) |

| More than 1 | 41 (23) |

| Nodal involvement | |

| Absent | 142 (79) |

| Present | 38 (21) |

| Percentage of blasts | |

| Less than 10% | 161 (89) |

| 10%-20% | 19 (11) |

| Bone marrow involvement | |

| Absent | 155 (86) |

| Present | 25 (14) |

| Autoimmune background | |

| Absent | 159 (88) |

| Present | 21 (12) |

| IPI | |

| Low to low-intermediate risk | 146 (81) |

| Intermediate/high to high risk | 31 (17) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) |

Initial primary extranodal lymphoma locations according to stage

| Extranodal site . | All patients, N (%) . | Stage I, N (%) . | Stage II, N (%) . | Stage IV, N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 180 (100) | 115 (100) | 16 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Skin | 22 (12) | 18 (16) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| Conjunctiva | 18 (10) | 18 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Orbit | 13 (7) | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| Salivary glands | 46 (26) | 39 (34) | 3 (19) | 4 (8) |

| Thyroid | 10 (6) | 6 (5) | 4 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Upper airways (+Waldeyer ring) | 12 (7) | 6 (5) | 2 (12) | 4 (8) |

| Lung | 15 (8) | 9 (8) | 3 (19) | 3 (6) |

| Breast | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Liver | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (12) |

| Bowel | 9 (5) | 5 (4) | 4 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Urinary tract | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multiple mucosal sites | 24 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (49) |

| Extranodal site . | All patients, N (%) . | Stage I, N (%) . | Stage II, N (%) . | Stage IV, N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 180 (100) | 115 (100) | 16 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Skin | 22 (12) | 18 (16) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| Conjunctiva | 18 (10) | 18 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Orbit | 13 (7) | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) |

| Salivary glands | 46 (26) | 39 (34) | 3 (19) | 4 (8) |

| Thyroid | 10 (6) | 6 (5) | 4 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Upper airways (+Waldeyer ring) | 12 (7) | 6 (5) | 2 (12) | 4 (8) |

| Lung | 15 (8) | 9 (8) | 3 (19) | 3 (6) |

| Breast | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Liver | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (12) |

| Bowel | 9 (5) | 5 (4) | 4 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Urinary tract | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Multiple mucosal sites | 24 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (49) |

Treatment and outcome

A total of 174 (97%) patients had lymphoma-directed treatment; in the remaining, a “wait and see” policy was adopted. Primary treatment included chemotherapy in 78 patients (in 36 cases with an anthracycline-based regimen); 12 of them had a combined modality approach (chemoradiotherapy). Forty-one patients had radiotherapy as the sole primary treatment. Sixty-eight patients had a surgical resection, alone (n = 27), followed by chemotherapy (n = 14), radiotherapy (n = 22), or both (n = 5). Four patients received interferon-α therapy and one, with a skin localization, had tumor regression after antibiotic therapy against Borrelia burgdorferi.34 Table 3shows the first-line therapy according to the Ann Arbor stage.

First-line therapy according to the stage of the disease

| Treatment modality . | No. of patients . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) . | Stage I-II . | Stage IV . | |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 78 (43) | 41 | 37 |

| With anthracycline | 36 (20) | 18 | 18 |

| Radiotherapy | 80 (44) | 72 | 8 |

| Alone | 41 (23) | 39 | 2 |

| Combined with chemotherapy | 12 (7) | 8 | 4 |

| Surgery | 68 (38) | 55 | 13 |

| Alone | 27 (15) | 22 | 5 |

| Followed by chemotherapy | 14 (8) | 8 | 6 |

| Followed by radiotherapy | 22 (12) | 21 | 1 |

| Followed by chemoradiotherapy | 5 (3) | 4 | 1 |

| Interferon-α | 4 (2) | 2 | 2 |

| Antibiotics | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 |

| No therapy | 6 (3) | 5 | 1 |

| Treatment modality . | No. of patients . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) . | Stage I-II . | Stage IV . | |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 78 (43) | 41 | 37 |

| With anthracycline | 36 (20) | 18 | 18 |

| Radiotherapy | 80 (44) | 72 | 8 |

| Alone | 41 (23) | 39 | 2 |

| Combined with chemotherapy | 12 (7) | 8 | 4 |

| Surgery | 68 (38) | 55 | 13 |

| Alone | 27 (15) | 22 | 5 |

| Followed by chemotherapy | 14 (8) | 8 | 6 |

| Followed by radiotherapy | 22 (12) | 21 | 1 |

| Followed by chemoradiotherapy | 5 (3) | 4 | 1 |

| Interferon-α | 4 (2) | 2 | 2 |

| Antibiotics | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 |

| No therapy | 6 (3) | 5 | 1 |

A total of 139 patients (77%; 95% CI, 70%-83%) patients achieved a CR and 29 (16%; 95% CI, 11%-22%) a PR after initial therapy with an overall response rate (ORR) of 93% (95% CI, 89%-97%). Among patients with stage IV disease, 28 (57%) had a CR and 17 (35%) a PR with an ORR of 92%. Among the patients receiving chemotherapy, the ORR was 92% with 72% CRs. The use of regimens containing anthracycline did not significantly improve the response rate in comparison with a single alkylating agent or CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone) regimen, neither in localized nor in advanced stage disease. Moreover, a chemotherapy program, with or without anthracycline, had no significant effect on OS, CSS, and PFS, even in disseminated disease.

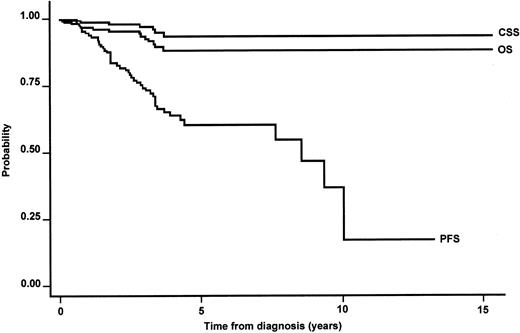

The median follow-up time was 3.4 years with 75% of cases followed for at least 4.9 years. The median OS was not reached. The estimated 5-year OS was 90% (95% CI, 82%-94%) in the whole series (Figure1). Twelve patients died, 6 patients from lymphoma progression and 4 of them after histologic transformation. All the lymphoma-related deaths occurred within 4 years from diagnosis. Table 4 provides information regarding the causes of death and their relationship with the main prognostic factors. The estimated 5-year CSS was 94% (95% CI, 87%-97%; Figure1). The 5-year PFS was 60% (95% CI, 50%-70%), with a median PFS of 8 years (Figure 1). Table 5 shows the outcome according to the primary site of localization, whereas Table6 summarizes the main clinical features at diagnosis according to the primary extranodal localization.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS, CSS, and PFS in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphomas.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS, CSS, and PFS in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphomas.

Causes of death and their relationship with major prognostic factors

| . | Overall . | Elevated LDH level . | Nodal disease . | Stage IV . | B symptoms . | Poor-risk IPI . | Histologic transformation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphoma progression | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Second tumor | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Cardiac disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| . | Overall . | Elevated LDH level . | Nodal disease . | Stage IV . | B symptoms . | Poor-risk IPI . | Histologic transformation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphoma progression | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Second tumor | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Cardiac disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

Outcome according to the primary extranodal site of localization

| Extranodal site . | 5-y survival rates, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OS (95% CI, %) . | CSS (95% CI, %) . | PFS (95% CI, %) . | |

| Skin | 100 | 100 | 53 (22-77) |

| Orbit | 80 (40-95) | 87 (39-98) | 23 (1-62) |

| Conjunctiva | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Salivary gland | 97 (81-100) | 97 (81-100) | 67 (48-81) |

| Upper airways | 46 (7-80) | 67 (5-95) | 0 |

| Lung | 100 | 100 | 75 (41-91) |

| Breast | 100 | 100 | 33 (1-77) |

| Thyroid | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Urinary tract | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bowel | 100 | 100 | 63 (24-87) |

| Multiple sites, all5-150 | 77 (43-93) | 86 (51-97) | 25 (3-58) |

| Multiple MALT organs, only | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| Extranodal site . | 5-y survival rates, % . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OS (95% CI, %) . | CSS (95% CI, %) . | PFS (95% CI, %) . | |

| Skin | 100 | 100 | 53 (22-77) |

| Orbit | 80 (40-95) | 87 (39-98) | 23 (1-62) |

| Conjunctiva | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Salivary gland | 97 (81-100) | 97 (81-100) | 67 (48-81) |

| Upper airways | 46 (7-80) | 67 (5-95) | 0 |

| Lung | 100 | 100 | 75 (41-91) |

| Breast | 100 | 100 | 33 (1-77) |

| Thyroid | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Urinary tract | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bowel | 100 | 100 | 63 (24-87) |

| Multiple sites, all5-150 | 77 (43-93) | 86 (51-97) | 25 (3-58) |

| Multiple MALT organs, only | 100 | 100 | 0 |

Patients with multiple MALT sites with or without nodal or bone marrow (or both) involvement.

Clinical features at diagnosis according to the primary localization

| Extranodal site . | Overall . | Elevated LDH level . | Nodal disease . | Stage IV . | B symptoms . | Poor-risk IPI . | Bone marrow . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 22 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Orbit | 13 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Conjunctiva | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salivary glands | 46 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Lung | 15 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Upper airways | 12 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Breast | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thyroid | 10 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 6 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Bowel | 9 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple MALT sites | 24 | 6 | 11 | 24 | 1 | 16 | 8 |

| Extranodal site . | Overall . | Elevated LDH level . | Nodal disease . | Stage IV . | B symptoms . | Poor-risk IPI . | Bone marrow . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 22 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Orbit | 13 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Conjunctiva | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salivary glands | 46 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Lung | 15 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Upper airways | 12 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Breast | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thyroid | 10 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver | 6 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Bowel | 9 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple MALT sites | 24 | 6 | 11 | 24 | 1 | 16 | 8 |

Analysis of prognostic factors

At univariate analysis, limited stage, a single extranodal site of involvement, absence of nodal involvement, and favorable IPI score were the main clinical features significantly associated with better OS, CSS, and PFS (Table 7). Normal serum LDH levels were associated with longer OS and PFS. An increased number of large cells (ie, ranging between 10% and 20%) displayed no statistically significant association with outcome. However, the cases with less than 10% large cells had a longer median PFS in comparison with those with 10% to 20% large cells (8 years versus 4 years), but this difference was not statistically significant, probably because of the very small number of events.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for OS, CSS, and PFS survival

| Features . | P by log-rank test . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OS . | CSS . | PFS . | |

| Ann Arbor stage IV | .0004 | .0034 | .0009 |

| Poor performance status (ECOG2 or higher) | NS | NS | NS |

| Presence of B symptoms | .007 | NS | NS |

| Elevated LDH level | .0396 | NS | .0027 |

| Extranodal involvement (2 sites or more) | .0051 | .0143 | .0013 |

| Age older than 60 y | NS | NS | NS |

| Elevated β2-microglobulin level | NS | .0357 | NS |

| Presence of nodal involvement | .0034 | .0004 | .0123 |

| Percentage of large cell infiltration (> 10%) | NS | NS | NS |

| IPI intermediate-high/high risk group | .0071 | .0035 | .0013 |

| Anthracycline-based chemotherapy | NS | NS | NS |

| Autoimmune disease | NS | NS | NS |

| HCV infection | NS | NS | NS |

| Bone marrow involvement | NS | NS | NS |

| Pattern of dissemination (multiple MALT sites only versus other stage IV) | .0001 | .0024 | .0038 |

| Features . | P by log-rank test . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OS . | CSS . | PFS . | |

| Ann Arbor stage IV | .0004 | .0034 | .0009 |

| Poor performance status (ECOG2 or higher) | NS | NS | NS |

| Presence of B symptoms | .007 | NS | NS |

| Elevated LDH level | .0396 | NS | .0027 |

| Extranodal involvement (2 sites or more) | .0051 | .0143 | .0013 |

| Age older than 60 y | NS | NS | NS |

| Elevated β2-microglobulin level | NS | .0357 | NS |

| Presence of nodal involvement | .0034 | .0004 | .0123 |

| Percentage of large cell infiltration (> 10%) | NS | NS | NS |

| IPI intermediate-high/high risk group | .0071 | .0035 | .0013 |

| Anthracycline-based chemotherapy | NS | NS | NS |

| Autoimmune disease | NS | NS | NS |

| HCV infection | NS | NS | NS |

| Bone marrow involvement | NS | NS | NS |

| Pattern of dissemination (multiple MALT sites only versus other stage IV) | .0001 | .0024 | .0038 |

NS indicates not significant.

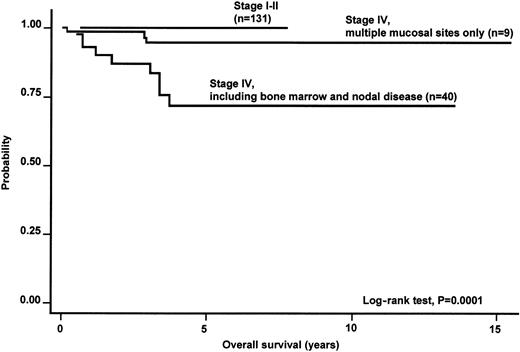

Within the category of stage IV disease, only the subgroup of patients with involvement of multiple MALT sites had a better survival (5-year OS, 100% versus 70%) than the remaining cases with stage IV, comprising those with multiorgan involvement or multifocal involvement of a single organ and additional bone marrow or nodal involvement (Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS according to the Ann Arbor stage of disease in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphoma.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS according to the Ann Arbor stage of disease in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphoma.

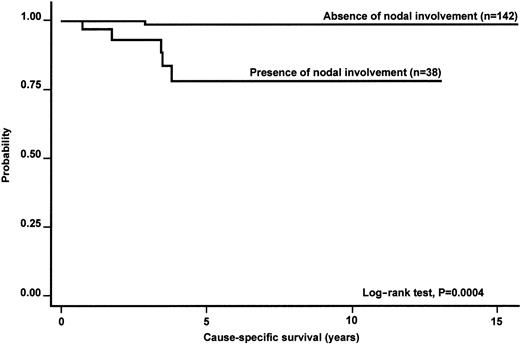

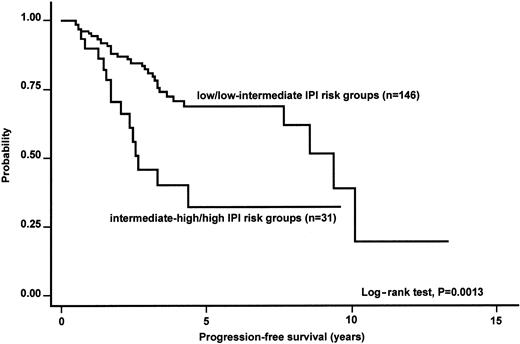

Table 8 summarizes the results of multivariate analysis. Despite the obvious limitations of Cox models with restricted number of events (only 10% death rate at 5 years), Ann Arbor stage retained its prognostic significance at multivariate analysis of OS. Nodal involvement was associated with a significantly higher relative risk of cause-specific death; a favorable IPI score was associated with a better PFS (Figures2-4).

Prognostic factors retaining predictive value at multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazards analysis)

| Survival, no. of patients/failures . | Relative risk . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS, 180/12 | |||

| Ann Arbor stage IV | 9.3 | 1.6-56 | .015 |

| CSS, 180/6 | |||

| Presence of nodal involvement | 11.2 | 1.1-114 | .04 |

| PFS, 177/47 | |||

| IPI intermediate-high/high risk group | 2.2 | 1.1-4.4 | .03 |

| Survival, no. of patients/failures . | Relative risk . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| OS, 180/12 | |||

| Ann Arbor stage IV | 9.3 | 1.6-56 | .015 |

| CSS, 180/6 | |||

| Presence of nodal involvement | 11.2 | 1.1-114 | .04 |

| PFS, 177/47 | |||

| IPI intermediate-high/high risk group | 2.2 | 1.1-4.4 | .03 |

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the CSS according to the presence of nodal involvement in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphomas.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the CSS according to the presence of nodal involvement in the whole series of primary nongastric MALT lymphomas.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the PFS according to the IPI risk groups.

The analysis was applicable to 177 patients.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the PFS according to the IPI risk groups.

The analysis was applicable to 177 patients.

Histologic transformation and development of second tumor

Histologic transformation into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was reported in 6 cases (3%; 95% CI, 1%-7%); notably, all these cases had no excess of large cells in their initial histology. The variables significantly associated with high-grade transformation were primary hepatic localization (P = .005), advanced stage disease (P = .03), and serologic evidence of previous HCV infection (P = .002). Large B-cell transformation was associated with a worse CSS (P < .05).

Eighteen patients (10%; 95% CI, 6%-15%) experienced the development of a second tumor.

Discussion

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is a discrete clinicopathologic entity arising in the MALT. Two types of MALT can be identified in disparate organs that do not correspond to peripheral sites of the immune system. The native type consists of lymphoid tissue physiologically present in the gut (eg, Peyer patches), whereas acquired MALT develops in sites of inflammation in response to either infectious conditions, such as Helicobacter pylorigastritis, or autoimmune processes, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis or myoepithelial sialadenitis associated with Sjögren syndrome.4,35,36 In the context of these prolonged lymphoid reactive proliferations, the growth of a pathologic clone can progressively replace the normal lymphoid population, giving rise to a MALT lymphoma.5,6,37 38

The peculiar pathogenetic features of primary gastric MALT lymphomas, with their implications on the clinical behavior of this entity,4 and data suggesting a distinct pattern of disease relapse and survival of the primary intestinal localizations39 led us to collect a series of primary nongastric MALT lymphomas including primary lymphomas of the small and large bowel.

In our series of cases collected from a variety of cancer centers, most of the patients had the lymphoma primarily localized in the salivary glands, in the ocular adnexa, or in the skin, but primary localizations in the lungs and upper airways were also often reported. The presence of a previous autoimmune disease, most often Sjögren syndrome, was significantly associated with a primary lymphoma of the salivary glands. A primary parotid lymphoma was also significantly associated with evidence of HCV infection. This result supports the possible, but controversial,40,41 role of HCV infection in the pathogenesis of salivary gland lymphomas, a role suggested at the molecular level by a peculiar pattern of rearrangement of the antigen receptor genes of salivary MALT lymphomas,42 analogous to the pattern of other HCV-related NHLs.43 44

A variable rate of large cells represents a common feature in marginal-zone lymphomas1,2; the presence of clusters or sheets of large cells suggests the emergence of a transformed clone and has been indicated as a marker of initial transformation into aggressive histiotypes. Many efforts have been made in identifying reliable criteria for the stratification of the low-grade lesions45 with respect to the percentage of infiltrative large cells, but they are confronted with the scarce reproducibility of the morphologic criteria.8 In the present series of histologically reviewed cases, despite the presence of a trend toward a poorer outcome for cases with an increased large cell rate, the small number of events probably prevented the statistical relevance of the finding.

Stage IV disease was present in more than one fourth of patients and multiple MALT organ localizations were observed at diagnosis in 13% of all patients. This proportion, apparently higher than that observed in primary gastric localizations, is comparable to those reported in other series and contradicts the common opinion of the MALT lymphomas as a typically localized disease,8,9 thus emphasizing the need of complete staging procedures in patients with MALT lymphomas.46 The preferential dissemination within the organs of the MALT system, likely due to the specific expression of special homing receptors or adhesion molecules on the surface of the B cells of MALT,23-25 may reflect an earlier phase of the natural history of the disease. According to this observation, in the group of patients with disseminated disease, the presence of multiple MALT-organ localizations without bone marrow or nodal disease appears to be associated with a better prognosis (Figure 2). On the contrary, the presence of nodal involvement or stage IV disease (characterized by cases with both nodal and extranodal disease and including cases with bone marrow involvement) identifies a group of patients with a worse prognosis (possible expression of a more advanced disease where the distribution of the B cells does not reflect anymore the physiologic lymphocyte traffic). Based on these observations, a 2-stage dissemination of MALT lymphomas could be postulated: one phase in which the disease first disseminates to other MALT sites and a second in which lymph node involvement occurs. The higher rate of multiple extranodal localizations in cases with nodal involvement appears in keeping with this hypothesis at least in a portion of cases.

In this multicentric retrospective survey of cases observed over a long period of time, patients were treated according to the current policy of each institution at the time of diagnosis, and the presence of organ-specific problems presumably had a role in the choice of treatment. At a median follow-up of 3.4 years there was no evidence of a clear advantage for any type of therapy and, despite the high proportion of cases with disseminated disease, which should require a systemic approach, no clear advantage was associated with a chemotherapy program.

In conclusion, as previously reported,46-48 nongastric MALT lymphomas, despite presenting with stage IV disease in approximately one fourth of cases, usually have a quite indolent course regardless of treatment type (5-year survival of 90%). The rate of histologic transformation seems much lower than in follicular lymphomas.49 Patients at high risk according to the IPI and those with lymph node involvement at presentation, but not those with involvement of multiple MALT sites, have a worse prognosis. Localization can be an important factor because of organ-specific problems, which result in particular management strategies. It seems that the incidence of the API2-MALT1 rearrangement or still unknown genetic lesions may be different at different sites.29 50 Whether different sites have a distinct natural history remains an open question; dissimilar prognostic variables at diagnosis might explain the observed differences (Table 6). In this IELSG series the patients with the disease initially presenting in the upper airways appeared to have a slightly poorer outcome (5-year OS, 46%), but their small number prevented any definitive conclusion.

The optimal management of MALT lymphomas has not been yet clearly defined. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy alone or in combination have been used. The treatment choice should be “patient-tailored,” taking into account the site, the stage, and the clinical characteristics of the individual patient. Preliminary data support the activity of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in MALT lymphoma51 and the efficacy of its combination with chemotherapy needs to be explored.

PATHOLOGY REVIEW PANEL

Renzo Barbazza, Servizio di Anatomia e Istologia Patologica, Ospedale Civile di Feltre, Feltre, Italy; Elias Campo, Laboratorio de Anatomia Patologica, Hospital Clı́nic i Provincial de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Carlo Capella, Anatomia e Istologia Patologica, Ospedale di Circolo Fondazione Macchi, Università dell'Insubria Varese, Italy; Roberto Giardini, Anatomia e Istologia Patologica, Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milano, Italy; Fabio Menestrina, Istituto di Anatomia e Istologia Patologica Ospedale Policlinico di Borgo Roma, Università di Verona, Verona, Italy; Teresio Motta, Anatomia Patologica e Citologia, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo, Bergamo, Italy; Domenico Novero, Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Oncologia Umana, Sezione Anatomia Patologica, Università di Torino, Italy; Bruce J. Patterson, Department of Hematopathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; Ennio Pedrinis, Istituto Cantonale di Patologia, Locarno, Switzerland; Stefano Pileri, Servizio di Anatomia Patologica ed Ematopatologia, Policlinico Sant'Orsola, Bologna, Italy; Maurilio Ponzoni, Servizio di Anatomia Patologica, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano, Italy; Giancarlo Pruneri, Divisione di Anatomia Patologica, Istituto Europeo di Oncologia, Milano, Italy; Paolo Rinaldi, Servizio di Anatomia Patologica e Citologia, Ospedale Civile Infermi, Rimini, Italy.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Emanuele Zucca, Annarita Conconi, Enrico Roggero, Franco Cavalli, Divisione di Oncologia Medica, Instituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana, Bellinzona, Switzerland; Sergio Cortelazzo, Tiziano Barbui, Divisione di Ematologia, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo, Bergamo, Italy; Mary K. Gospodarowicz, Department of Radiation Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; Stefania Dell'Oro, Andrés J. M. Ferreri, Servizio di Radiochemioterapia, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano, Italy; Carlo Tondini, Salvatore Grisanti, Liliana Devizzi, Massimo A. Gianni, Divisione di Oncologia Medica, Istituto Nazionale per lo Studio e la Cura dei Tumori, Milano, Italy; Claudio Chini, Leonardo Campiotti, Graziella Pinotti, Servizio di Oncologia Medica, Ospedale di Circolo di Varese, Varese, Italy; Pier Luigi Zinzani, Divisione di Ematologia, Policlinico Sant'Orsola, Bologna, Italy; Armando López-Guillermo, Emilio Monserrat, Clı́nic Servicio de Hematologia, Hospital Universitari, Barcelona, Spain; Claudia Crippa, Achille Ambrosetti, Divisione di Ematologia, Policlinico G. B. Rossi, Verona, Italy; Maria Goldaniga, Stefano Luminari, Luca Baldini, Giorgio Lambertenghi Deliliers, Servizio di Ematologia Ospedale Maggiore IRCCS, Milano, Italy; Michele de Boni, Servizio di Gastroenterologia ed Endoscopia Digestiva, Ospedale Civile di Feltre, Feltre, Italy; Marilena Bertini, Divisione di Ematologia, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Giovanni Battista, Torino, Italy; Monica Balzarotti, Dipartimento di Oncologia Medica ed Ematologia, Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Milano, Italy; Lorenzo Gianni, Giuliana Drudi, Alberto Ravaioli, Divisione di Oncologia Ospedale Civile Infermi, Rimini, Italy; Giovanni Martinelli, Divisione di Ematoncologia Clinica, Istituto Europeo di Oncologia, Milano, Italy; Katia Cagossi, Fabrizio Artioli, Divisione di Medicina Oncologica, Ospedale “Ramazzini,” Carpi, Italy.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 27, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1279.

Supported in part by the Swiss Cancer League/Cancer Research Switzerland (grant no. SKL 652-2-1998).

E.Z. and A.C. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Emanuele Zucca, International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group, c/o Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Ospedale San Giovanni, 6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland; e-mail:ielsg@ticino.com.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal