The sideroblastic anemias are characterized by ring sideroblasts, that is, red cell precursors with mitochondrial iron accumulation. We therefore studied the expression of mitochondrial ferritin (MtF) in these conditions. Erythroid cells from 13 patients with refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) and 3 patients with X-linked sideroblastic anemia (XLSA) were analyzed for the distribution of cytoplasmic H ferritin (HF) and MtF using immunocytochemical methods. We also studied 11 healthy controls, 5 patients with refractory anemia without ring sideroblasts (RA), and 7 patients with RA with excess of blasts (RAEB). About one fourth of normal immature red cells, mostly proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts, showed diffuse cytoplasmic positivity for HF, but very few were positive for MtF (0%-10%). Similar patterns were found in anemic patients without ring sideroblasts. In contrast, many erythroblasts from patients with sideroblastic anemia (82%-90% in XLSA and 36%-84% in RARS) were positive for MtF, which regularly appeared as granules ringing the nucleus. Double immunocytochemical staining confirmed the different cellular distribution of HF and MtF. There was a highly significant relationship between the percentage of MtF+ erythroblasts and that of ring sideroblasts (SpearmanR = 0.90; P < .0001). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction studies demonstrated the presence of MtF mRNA in circulating reticulocytes of 2 patients with XLSA but not in controls. These findings suggest that most of the iron deposited in perinuclear mitochondria of ring sideroblasts is present in the form of MtF and that this latter might be a specific marker of sideroblastic anemia.

Introduction

The sideroblastic anemias are a heterogeneous group of disorders that have in common the presence of ring sideroblasts in more than 10% to 15% of nucleated red cells.1 After Prussian blue staining of iron deposited in individual erythroblasts (Perls stain), ring sideroblasts are identified as immature red cells in which 10 or more blue granules representing iron-loaded mitochondria form a ring around the nucleus. The sideroblastic anemias display remarkable clinical and hematologic heterogeneity,2,3 but share this mitochondrial iron loading. Despite recent advances in our understanding of iron metabolism,4 the abnormal mitochondrial iron metabolism that characterizes these conditions is poorly understood.

Using an immunocytochemical approach we have previously shown that much of the extra cytosolic iron in normal bone marrow and peripheral blood cells is incorporated into ferritin.5Ferritin is a ubiquitous protein that plays a critical role in regulating intracellular iron homeostasis by storing iron inside its multimeric shell.6 It also plays an important role in detoxifying potentially harmful free ferrous iron to the less soluble ferric iron by virtue of the ferroxidase activity of the H subunit.7 Little is yet known about how iron is detoxified in mitochondria or about the forms of iron in iron-loaded mitochondria in different disorders.

Some of us have recently described an intronless ferritin gene that encodes a mitochondrial ferritin (MtF) with ferroxidase activity.8 Because overexpression of MtF in HeLa cells reduces the cytosolic ferritin and induces transferrin receptor expression, this protein might play an important role in regulating mitochondrial iron homeostasis and heme synthesis.9Northern blot analysis indicated that the gene is highly expressed in the testis, and preliminary immunocytochemical studies showed the presence of MtF in a patient with sideroblastic anemia.8Here we present a comprehensive analysis of the expression of this protein in patients with inherited or acquired sideroblastic anemia and in patients with other refractory anemias of unknown etiology. These studies provide evidence that MtF is almost exclusively expressed in ring sideroblasts and may represent a specific marker of sideroblastic anemia.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and healthy controls

We studied 25 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and 3 patients with X-linked sideroblastic anemia (XLSA) followed at the Department of Hematology and Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Therapy, University of Pavia Medical School and IRCCS Policlinico S Matteo, Pavia, Italy. Based on the World Health Organization criteria,10 MDS patients were categorized as having refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS, n = 13), refractory anemia without ring sideroblasts (RA, n = 5), or refractory anemia with excess of blasts (RAEB, n = 7). After Perls staining, sideroblasts were classified as follows: (a) type 1 sideroblasts, that is, cells showing few (≤ 5) small iron-containing granules; (b) type 2 sideroblasts, that is, cells showing more numerous (6-9) rather large granules, diffusely scattered in the cytoplasm; and (c) type 3 or ring sideroblasts, that is, erythroblasts characterized by many granules (≥ 10) surrounding at least one third of the circumference of the nucleus.

Patients with MDS categorized as having RARS showed 19% to 87% ring sideroblasts in their bone marrow. Patients with XLSA had a microcytic congenital anemia associated with the presence of ringed sideroblasts in the bone marrow. In all of them, missense mutations in the erythroid-specific 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS2)gene were demonstrated using previously described methods.11

The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Immunocytochemical studies were performed on peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirates performed exclusively for diagnostic purposes. In some instances, bone marrow smears prepared with fresh material were cryopreserved at −20°C before these immunocytochemical investigations. In a few patients, RNA was obtained from peripheral blood (about 30 mL); informed consent was obtained from each subject, although in patients with XLSA these investigations were performed during venesection treatment of secondary iron overload.12

Normal bone marrow aspirates were obtained from marrow donors (Bone Marrow Transplantation Center, Division of Hematology, University of Pavia Medical School and IRCCS Policlinico S Matteo, Pavia, Italy) and from nonanemic patients showing no marrow involvement through routine diagnostic investigations. As far as bone marrow donations are concerned, each bone marrow is routinely immunophenotyped according to the Center's policy. In this study, pellets remaining after flow cytometry investigations were used to prepare bone marrow smears.

Immunocytochemical investigations

Erythroid cells on formalin-fixed bone marrow smears were analyzed for the distribution of cytoplasmic H ferritin (HF) using a monoclonal mouse antibody (rH02) as before,5 and for MtF with a polyclonal antibody raised in rabbits and mice against and specific for MtF.8 Bound antibody was detected by an immuno-alkaline phosphatase method (streptavidin-biotin complex, LSAB2 kit; Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark). Negative controls were performed by replacing the primary antibody with nonimmune mouse or rabbit serum. In each case the percentage of positive erythroblasts was recorded.

A double-labeling, 2-color technique to detect HF and MtF simultaneously was performed on bone marrow smears from a patient with XLSA and 2 with RARS. An immuno-alkaline phosphatase reaction was used for HF staining; then, on the same slides, MtF was detected by an immuno-β-galactosidase reaction. Finally, slides were counterstained with Mayer hemalum.

Expression of MtF mRNA in peripheral blood reticulocytes

Reticulocyte RNA was isolated from the peripheral red cells as described in detail by Goossens and Kan.13 MtF mRNA was reverse transcribed and amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using 250 ng random hexamers with 200 U superscript II (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) in a final volume of 20 μL and was amplified with PCR. The method used primers T1 TATTTCCTTCACCAGTCCCGG and T4R AGAGCGTGCAATTCCAGCAAC, which generated a fragment of 204 base pair (bp). Cycling conditions were as follows: 2 minutes at 94°C, 45 cycles (30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 57°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C), followed by 7 minutes at 72°C. For higher sensitivity, in some samples we used a seminested PCR in which the PCR was preceded by a first step that used primers Ft1M CCCGGGACCTACCGGGCCCG and T4R AGAGCGTGCAATTCCAGCAAC, which generated a fragment of 385 bp. Cycling conditions were as follows: 2 minutes at 94°C, 45 cycles (30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 57°C, and 40 seconds at 72°C), followed by 7 minutes at 72°C. PCR was performed in 50 μL containing the following: 25 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 × PCR buffer (Sigma, Milan, Italy), 200 μM of each dNTPs (Roche, Monza, Italy), and 1 UTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma). Amplification products were then evaluated by electrophoresis. Analyses were run in parallel with controls without reverse transcriptase (RT), which always gave negative results.

Results

In normal erythroblasts, HF positivity was observed in about one fourth of the elements, mostly in proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts (Table 1; Figure1A). It should be noted that the monoclonal antibody anti-HF reacts strongly with ferritins containing H subunits but has little if any reactivity to MtF. The reactivity pattern was generally diffuse, but positivity was sometimes more intense in small areas of the cytoplasm. In these cases, the staining pattern of H-ferritin proteins was similar to the particulate Perls pattern, suggesting that much of the iron was associated with these ferritin shells.

Mitochondrial and H ferritin expression, and Perls Prussian blue stain of iron in immature red cells from healthy individuals and anemic patients

| . | MtF+erythroblasts, % . | HF+ erythroblasts, % . | Perls Prussian blue stain, % positive erythroblasts . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring sideroblasts . | Type 1 and 2 ferritin sideroblasts . | |||

| Healthy controls (n = 11) | 4 (0-10) | 24 (8-64) | 0 | 32 (16-52) |

| XLSA (n = 3) | 84, 82, 90 | 6, 33, 36 | 88, 77, 89 | 10, 15, 11 |

| RARS (n = 13) | 60 (36-84) | 30 (12-80) | 45 (19-87) | 27 (8-51) |

| RA (n = 5) | 7 (6-20) | 26 (16-62) | 1 (0-6) | 68 (60-90) |

| RAEB (n = 7) | 7 (0-24) | 24 (4-51) | 2 (0-14) | 25 (8-74) |

| . | MtF+erythroblasts, % . | HF+ erythroblasts, % . | Perls Prussian blue stain, % positive erythroblasts . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring sideroblasts . | Type 1 and 2 ferritin sideroblasts . | |||

| Healthy controls (n = 11) | 4 (0-10) | 24 (8-64) | 0 | 32 (16-52) |

| XLSA (n = 3) | 84, 82, 90 | 6, 33, 36 | 88, 77, 89 | 10, 15, 11 |

| RARS (n = 13) | 60 (36-84) | 30 (12-80) | 45 (19-87) | 27 (8-51) |

| RA (n = 5) | 7 (6-20) | 26 (16-62) | 1 (0-6) | 68 (60-90) |

| RAEB (n = 7) | 7 (0-24) | 24 (4-51) | 2 (0-14) | 25 (8-74) |

Median values are given, with ranges in parentheses. For the 3 patients with XLSA, their individual values are listed.

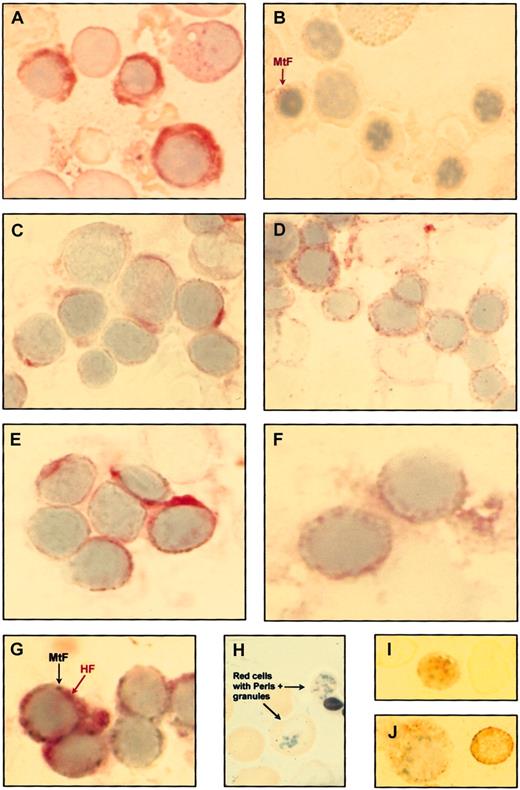

Immunocytochemical studies on bone marrow and peripheral blood smears from healthy controls and patients with sideroblastic anemia.

(A) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from a healthy control using the monoclonal antibody rH02 specific for the H subunit of ferritin shows strong diffuse positivity in the cytoplasm of some erythroblasts. (B) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from the previous healthy control using a polyclonal antibody raised against the MtF. Most erythroblasts are negative; the erythroblast on the left (arrow) shows weak positivity. (C) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from a patient with XLSA using the anti-HF monoclonal antibody shows diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in a few erythroblasts. (D) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from the previous XLSA patient. Many erythroblasts are positive with granules ringing the nucleus. (E) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for HF of bone marrow cells from a patient with RARS. Diffuse cytoplasmic positivity is present in some erythroblasts. (F) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from the previous patient with RARS. Positivity with granules surrounding the nucleus is present in 2 erythroblasts. (G) Double immunocytochemical staining for HF (immuno-alkaline phosphatase reaction) and MtF (immuno-β–galactosidase reaction) on a bone marrow smear from a patient with XLSA. The cellular distributions of HF and MtF are quite different, HF being diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (red staining) and MtF localized in perinuclear granules (turquoise staining). (H) Perls Prussian blue staining of a peripheral blood smear from a patient with RARS; positive granules are visible in 2 red cells. (I) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of peripheral blood smear from a patient with RARS; unequivocal positivity is observable in a circulating red cell. (J) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from a patient with XLSA; a positive erythroblast (on the left) and a positive red cell (on the right) are shown. Original magnification, × 1250.

Immunocytochemical studies on bone marrow and peripheral blood smears from healthy controls and patients with sideroblastic anemia.

(A) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from a healthy control using the monoclonal antibody rH02 specific for the H subunit of ferritin shows strong diffuse positivity in the cytoplasm of some erythroblasts. (B) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from the previous healthy control using a polyclonal antibody raised against the MtF. Most erythroblasts are negative; the erythroblast on the left (arrow) shows weak positivity. (C) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining of bone marrow cells from a patient with XLSA using the anti-HF monoclonal antibody shows diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in a few erythroblasts. (D) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from the previous XLSA patient. Many erythroblasts are positive with granules ringing the nucleus. (E) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for HF of bone marrow cells from a patient with RARS. Diffuse cytoplasmic positivity is present in some erythroblasts. (F) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from the previous patient with RARS. Positivity with granules surrounding the nucleus is present in 2 erythroblasts. (G) Double immunocytochemical staining for HF (immuno-alkaline phosphatase reaction) and MtF (immuno-β–galactosidase reaction) on a bone marrow smear from a patient with XLSA. The cellular distributions of HF and MtF are quite different, HF being diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (red staining) and MtF localized in perinuclear granules (turquoise staining). (H) Perls Prussian blue staining of a peripheral blood smear from a patient with RARS; positive granules are visible in 2 red cells. (I) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of peripheral blood smear from a patient with RARS; unequivocal positivity is observable in a circulating red cell. (J) Immuno-alkaline phosphatase staining for MtF of bone marrow cells from a patient with XLSA; a positive erythroblast (on the left) and a positive red cell (on the right) are shown. Original magnification, × 1250.

Similar analyses were performed with an antiserum directed against MtF that reacts strongly with MtF but has little if any cross-reactivity with cytosolic H and L ferritins. These analyses (Figure 1B) showed that fewer normal erythroblasts stained for MtF than for Perls stain or cytosolic HF (range, 0%-10%; median value, 4%). No specific staining for HF or MtF was observed in circulating red cells from healthy individuals.

Studies of iron, HF, and MtF distribution were then performed in anemic patients. Some of these individuals had ring sideroblasts, whereas others had a refractory anemia with no ring sideroblasts in their marrow (Table 1). Variable proportions of marrow erythroblasts from anemic patients were found to be positive for HF (Table 1), as previously reported,5 but no specific pattern was observed in different disease groups. In particular, there was no significant difference in HF levels between sideroblastic anemias and the remaining refractory anemias without ring sideroblasts.

More discernible differences in staining patterns were observed when bone marrow smears from anemic patients were examined for MtF expression (Figure 1C-F). In patients with RA, a small proportion (0%-24%) of marrow erythroblasts were positive. By contrast, in patients with sideroblastic anemia many erythroblasts (82%-90% in XLSA and 36%-82% in RARS) were positive for MtF. One-way analysis of variance showed a significant difference in the percentage of MtF+ immature red cells between anemic patients with ring sideroblasts (median value, 70%; range, 36%-90%) and anemic patients without ring sideroblasts (median value, 7%; range, 0%-24%; F = 79; P < .00001). In patients with sideroblastic anemia, MtF was detected in immature red cells at all stages of maturation, and in all cases the positivity presented granules ringing the nucleus (Figure 1D,F). By contrast, HF was detected in only some of these erythroblasts, and it had a diffuse rather than a particulate distribution (Figure 1C,E). As shown in Figure 1G, double immunocytochemical staining confirmed the different cellular distribution of HF and MtF in immature red cells from patients with sideroblastic anemia.

In a few patients with sideroblastic anemia we were able to identify the so-called siderocytes after Perls staining of peripheral blood smears (Figure 1H). These individuals also showed occasional red cells that stained positive for MtF but not for HF (Figure 1I-J).

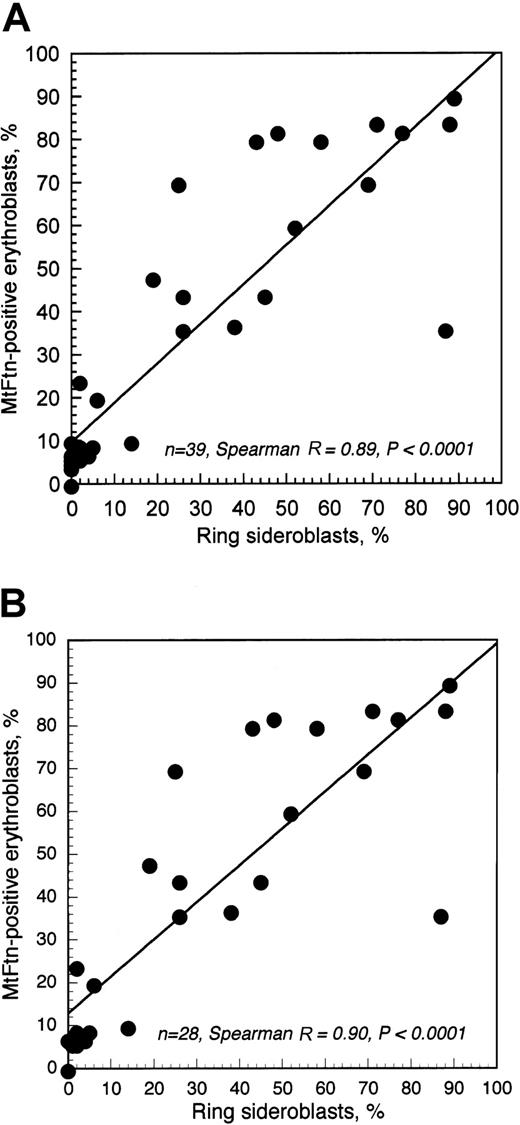

Rank correlation analysis showed a close relationship between the percentage of ring sideroblasts and that of MtF+erythroblasts (Figure 2). This was observed both when healthy controls were (SpearmanR = 0.89; P < .0001) or were not (SpearmanR = 0.90; P < .0001) included in the analysis. In any case, about 80% of variation in the percentage of MtF+ erythroblasts was explained by variation in ring sideroblasts, again indicating that MtF was almost exclusively expressed in these latter.

Relationship between percentage of ring sideroblasts and that of MtF+ erythroblasts.

(A) Relationship in healthy controls and anemic patients; (B) relationship in anemic patients only.

Relationship between percentage of ring sideroblasts and that of MtF+ erythroblasts.

(A) Relationship in healthy controls and anemic patients; (B) relationship in anemic patients only.

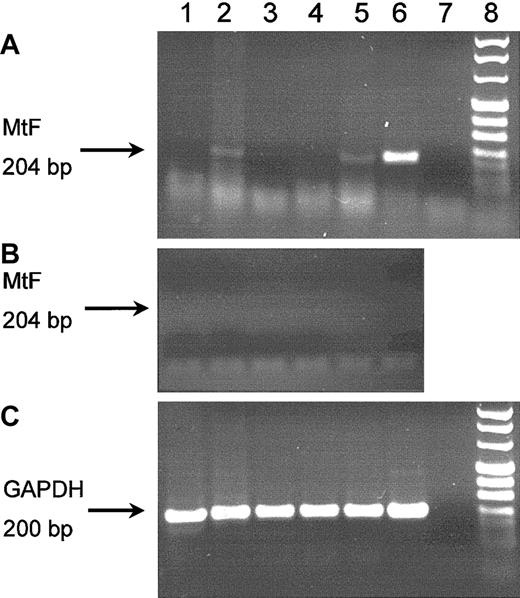

Because preliminary experiments showed that MtF mRNA was undetectable in normal bone marrow by Northern blot analysis (data not shown), we used a more sensitive RT-PCR technique to detect it in the peripheral blood reticulocytes. MtF mRNA expression was studied in subjects with mutations in the ALAS2 gene that can cause XLSA and in 3 individuals with acquired sideroblastic anemia of unknown etiology. The former patients included: (a) a hemizygous man with clinically manifest XLSA from the ALAS2 Cys395Tyr mutation12; (b) 2 nonanemic women who are heterozygous for ALAS2 Cys395Tyr; and (c) 2 hemizygous men with the ALAS2 Arg560His mutation, of whom only one has the clinical features of XLSA.14This analysis showed that MtF mRNA was present in both hemizygous men (Figure 3 lanes 2 and 5) with overt clinical symptoms, that is, microcytic anemia with iron overload.17 By contrast, no MtF mRNA amplimer was detected in peripheral blood reticulocytes from the nonanemic heterozygous women (Figure 3, lanes 1 and 3), or from the nonanemic hemizygous man with the ALAS2 Arg560His mutation (Figure 3, lane 4). A similar analysis on peripheral blood reticulocytes from 3 patients with acquired sideroblastic anemia who had consented to these investigations failed to detect any MtF mRNA even when a more sensitive seminested RT-PCR method was used (data not shown).

RT-PCR evaluation of MtF mRNA expression in peripheral blood reticulocytes.

DNAase-treated mRNA preparations were reverse transcribed and PCR amplified, and amplification products were then evaluated by electrophoresis. Panel A shows an RT-PCR study using MtF specific-oligonucleotides (45 cycles); in lanes 2, 5, and 6, a fragment of 204 bp (indicated by the arrow) is clearly observable. The fragment was digested by BamHI to confirm the identity of the product as MtF. Panel B shows the negative findings of the control study without RT treatment. The arrow indicates the expected position of the 204-bp amplicon. Panel C shows an RT-PCR study using oligonucleotides specific for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); in all lanes but one (the negative control), a band of 200 bp (indicated by the arrow) is visible. Lanes 1 and 3: heterozygous women with the ALAS2 Cys395Tyr mutation.12 Lane 2: hemizygous man with the ALAS2 Cys395Tyr mutation and clinically manifest XLSA.12 Lanes 4 and 5: hemizygous men (brothers) with the ALAS2 Arg560His mutation and absent phenotypic expression of the disease (lane 4) or clinically manifest XLSA (lane 5).14 Lane 6: HeLa cells expressing the MtF gene after transfection. Lane 7: water. Lane 8: molecular markers.

RT-PCR evaluation of MtF mRNA expression in peripheral blood reticulocytes.

DNAase-treated mRNA preparations were reverse transcribed and PCR amplified, and amplification products were then evaluated by electrophoresis. Panel A shows an RT-PCR study using MtF specific-oligonucleotides (45 cycles); in lanes 2, 5, and 6, a fragment of 204 bp (indicated by the arrow) is clearly observable. The fragment was digested by BamHI to confirm the identity of the product as MtF. Panel B shows the negative findings of the control study without RT treatment. The arrow indicates the expected position of the 204-bp amplicon. Panel C shows an RT-PCR study using oligonucleotides specific for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); in all lanes but one (the negative control), a band of 200 bp (indicated by the arrow) is visible. Lanes 1 and 3: heterozygous women with the ALAS2 Cys395Tyr mutation.12 Lane 2: hemizygous man with the ALAS2 Cys395Tyr mutation and clinically manifest XLSA.12 Lanes 4 and 5: hemizygous men (brothers) with the ALAS2 Arg560His mutation and absent phenotypic expression of the disease (lane 4) or clinically manifest XLSA (lane 5).14 Lane 6: HeLa cells expressing the MtF gene after transfection. Lane 7: water. Lane 8: molecular markers.

Discussion

In this study we have compared the distribution of stainable iron with cytosolic and mitochondrial ferritins in erythroblasts from patients with different forms of anemia and have shown that MtF is almost exclusively expressed in sideroblastic anemia. In addition to these results, these studies provide new insights into the metabolism of iron and ferritins in erythroid cells.

Most of the iron used in erythroblasts for hemoglobin synthesis is thought to come from transferrin internalized on the transferrin receptor (for a more comprehensive discussion of this topic, see the excellent review by Ponka15). Within erythroid cells, the excess iron is stored in ferritin molecules that partially aggregate within specific endosomes called siderosomes.16 These latter are stained by the Perls reaction in about one third of normal immature red cells, and these erythroblasts with few Perls-positive granules scattered in the cytoplasm are defined as “ferritin sideroblasts.”1 The number of these ferritin-type sideroblasts typically increases in iron-loading anemias, such as thalassemia intermedia, and more generally whenever the iron supply to the erythroid marrow exceeds the amount required for hemoglobin synthesis.1 Ring sideroblasts differ from the ferritin-type ones in 2 features: (a) Perls-positive granules tend to form a ring surrounding the nucleus, and(b) more important, the stained granules are iron-loaded mitochondria rather than cytoplasmic siderosomes.

The nature of the excess mitochondrial iron of ring sideroblasts has remained an enigma for many years but has now been clarified by our present findings that most of the iron is very likely present as MtF. We have shown, in fact, that most immature red cells with mitochondrial iron granules, and exclusively these cells, express MtF; since MtF is highly efficient in incorporating iron,9 it can be safely inferred that the iron is deposited inside these protein shells. This observation has considerable pathophysiologic and clinical implications.

XLSA is caused by mutations (primarily missense) in theALAS2 gene.17 Altered substrate interaction, reduced affinity for pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP), reduced apoenzyme stability, or inappropriate/absent mitochondrial processing may account for the defective ALAS2 activity in bone marrow erythroblasts of patients with XLSA.18 All of these can result in insufficient protoporphyrin IX synthesis. Because iron uptake in these cells has already been switched on by increases in transferrin receptor expression,15 massive amounts of iron accumulate inside these cells. For reasons yet unknown, much of this iron goes to the mitochondria. Our studies indicate that in sideroblastic anemia much of this excess iron is present as MtF rather than as insoluble aggregates of inorganic iron; this is an intriguing finding for MtF expression and for mitochondrial iron homeostasis.

In most cells, the level of cytoplasmic ferritin is mainly controlled by the levels of free iron through translational control of H and L ferritin synthesis by an iron responsive element (IRE) in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA.19,20 However, normal immature red cells contain very little ferritin in their cytosol or mitochondria despite a massive influx of iron for heme synthesis (Figure 1A-B). This finding suggests that the large amount of iron entering these cells does not appreciably increase levels of free iron in their cytosol.15 If so, most of the transferrin iron that has been internalized on the transferrin receptor may be preferentially targeted to the mitochondrion rather than released into the cytosol, and be immediately used for heme synthesis.15On the other hand, the levels of cytosolic and mitochondrial ferritins both increase when heme synthesis is disrupted in sideroblastic anemia. The increase in cytosol ferritins is probably due to increased translation because of an increase in the free iron in the cytosol. However, the gene for MtF lacks a recognizable IRE for translational control8; other mechanisms may, therefore, be responsible for the dramatic increases in MtF levels associated with ring sideroblasts.

Although the increased MtF level might be caused by iron-induced stabilization of the protein, this seems unlikely because protein degradation in the experimental cellular model was slow and not affected by cellular iron loading.9 Transcriptional control of MtF by iron is possible as has been indicated in HeLa cells,9 and our RT-PCR findings would be more consistent with this hypothesis. Feedback inhibition of MtF gene expression by protoporphyrin IX synthesis, as occurs with frataxin and protoporphyrin IX,21 might account for the differences in MtF expression in normal erythroblasts and ring sideroblasts. This might explain why we found MtF mRNA expression (Figure 3) only in cases of XLSA, in which protoporphyrin IX synthesis is markedly reduced and a significant portion of circulating reticulocytes represent the progeny of nucleated red cells expressing MtF.17 By contrast, none of the 3 patients with RARS who were investigated had evidence of MtF mRNA in their reticulocytes, despite the fact that their bone marrow erythroblasts stained positive for the protein. In such patients, most of the abnormal erythroid precursors undergo apoptosis and die prematurely in the bone marrow; because very few of them escape apoptosis, only very few circulating reticulocytes, if any, contain residual MtF mRNA.

Our findings may also be relevant to the pathophysiology of RARS because they support the hypothesis that a primary defect in this condition may be an abnormality of mitochondrial iron metabolism.22 On the contrary, the fact that MtF gene maps on chromosome 5q23.1 does not appear to have implications for the pathogenesis of the so-called 5q− syndrome. In fact, the present evidence suggests that it will not be involved in this syndrome because the deletions appear to involve mainly 5q21 or 5q31.23

Finally, this study might have practical implications. Specific immunodetection of MtF should allow the development of diagnostic tools for sideroblastic anemias. Immunophenotyping should be more specific and reliable than the conventional Perls reaction, because it is often difficult to differentiate ring sideroblasts from ferritin sideroblasts.24 We25 and others26 have shown that RARS may present as a pure erythroid disorder or an MDS with multilineage defects, and that these conditions differ considerably in terms of morbidity, risk of leukemic transformation, and survival. Should evaluation of MtF expression allow the 2 conditions to be distinguished at clinical onset, this approach would represent a valuable tool for determining the diagnosis and prognosis of MDSs.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 24, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2006.

Supported by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, Research Project entitled “Functional and molecular profiling of hematopoietic stem cells in myelodysplastic syndromes”), Milan, Fondazione Ferrata Storti, Pavia, and IRCCS Policlinico S Matteo, Pavia (M.C.); from Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR), Rome, Italy (Cofin 2000 and 2002; M.C., P.A.); and from Telethon, Milan, Italy (grant no. GP0075Y01; S.L.).

M.C. and R.I. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mario Cazzola, Division of Hematology, IRCCS Policlinico S Matteo, 27100 Pavia, Italy; e-mail:mario.cazzola@unipv.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal