Adoptive transfer of allogeneic T cells has unmatched efficacy to eradicate leukemic cells. We therefore sought to evaluate in kinetic terms interactions between T cells and allogeneic leukemic cells. T cells primed against the model B6dom1 minor histocompatibility antigen were adoptively transferred in irradiated B10 (B6dom1-positive) and congenic B10.H7b (B6dom1-negative) recipients, some of which were also injected with EL4 leukemia/lymphoma cells (B6dom1-positive). A key finding was that the tissue distribution of the target epitope dramatically influenced the outcome of adoptive cancer immunotherapy. Widespread expression of B6dom1 in B10 recipients induced apoptosis and dysfunction of antigen-specific T cells. Furthermore, in leukemic B10 and B10.H7b hosts, a massive accumulation of effector/memory B6dom1-specific T cells was detected in the bone marrow, the main site of EL4 cell growth. The accumulation of effector/memory cells in recipient bone marrow was EL4 dependent, and its kinetics was different from that observed in recipient spleen. We conclude that strategies must be devised to prevent apoptosis of adoptively transferred T cells confronted with a high antigen load and that local monitoring of the immune response at the site of tumor growth may be mandatory for a meaningful assessment of the efficacy of adoptive immunotherapy.

Introduction

T-cell immunosurveillance can prevent the development of several malignancies. Nevertheless, the common occurrence of neoplasia shows that cancer immunosurveillance is leaky. Not only are cancer cells commonly ignored by the immune system, they can induce anergy or deletion of tumor-reactive T cells. In addition, it has proven exceedingly difficult to elicit curative immune responses with tumor vaccines.1,2 Several factors explain the disappointing results obtained in tumor vaccine trials: low immunogenicity of tumor-associated epitopes, absence of high-avidity tumor-reactive T cells in the peripheral T-cell repertoire, location of cancer cells outside the secondary lymphoid organs, and microenvironmental features in the tumor cell stroma (physical barriers, cytokines) that hinder productive interactions between T cells and cancer cells.3-7

Many drawbacks of tumor vaccines can be curtailed by the use of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy.8 Indeed, the T-cell repertoire from an allogeneic donor comprises T lymphocytes that can recognize with high avidity non–self-epitopes expressed by recipient cancer cells. Furthermore, these T cells can be primed ex vivo against their target antigen before adoptive transfer. Injected cells can be self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–restricted T lymphocytes that recognize polymorphic MHC-associated peptides—that is, minor histocompatibility antigens (MiHA)—or they can be allo-MHC restricted.9-13 Many clinical studies have shown that a single injection of allogeneic lymphocytes can eradicate up to 1012 hematopoietic malignant cells.14-17 The remarkable efficacy of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy in eradicating leukemia/lymphoma cells probably constitutes the most convincing evidence that T lymphocytes can cure established cancer.15Moreover, recent studies suggest that the efficacy of adoptive immunotherapy can be extended to the treatment of solid tumors.18,19 The use of this approach however, has been limited by the fact that unselected allogeneic T cells can recognize epitopes present on normal host cells, thereby causing graft-versus-host disease. Nevertheless, we recently showed that the injection of T cells that selectively recognize an immunodominant MiHA, B6dom1, expressed at high levels on hematopoietic cells, can eradicate malignant hematopoietic cells without causing graft-versus-host disease.20 B6dom1 is an H2Db-associated immunodominant peptide encoded by theH7 locus at the telomeric end of mouse chromosome 9 that is ubiquitously expressed but is 10 times more abundant on hematopoietic than on nonhematopoietic cells.20-22

The B6dom1 model is an informative paradigm for cancer immunotherapy because the desired outcome, efficient eradication of cancer cells without toxicity to the host, can be achieved relatively easily by targeting this epitope. Furthermore, the conclusions drawn by studying B6dom1-specific T-cell responses may be generally applicable because B6dom1 is a natural MHC-associated peptide expressed at physiological levels rather than, for example, the product of a transfected viral gene. The aim of the present work was to evaluate in kinetic terms the interactions between adoptively transferred CD8 T cells and allogeneic cancer cells using B6dom1 as a model target antigen. More specifically, we asked the following questions: (1) What is the level and duration of B6dom1-specific T-cell expansion following adoptive transfer to cancer-bearing mice? (2) What is the pace of cancer cell eradication? These questions address important issues related to our understanding of how T-lymphocyte responses against cancer cells compare with those against microbial pathogens.

Materials and methods

Mice

B10.C-H7b(47N)/Sn (B10.H7b) and C57BL/10J (B10) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were bred at the Guy-Bernier Research Center.

Tumor cells

The EL4 leukemia/lymphoma cell line (of C57BL/6 origin) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and was cultured in Dulbecco modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% horse serum, penicillin–streptomycin, andl-glutamine. Because they are derived from a C57BL/6 mouse, EL4 cells differ from B10 cells at the H9 locus, which encodes a nondominant MiHA. H9 disparity elicits no detectable anti-EL4 response in vivo.20

Cell transplantation

Recipient mice received 1200 cGy total body irradiation from a cobalt 60 source at a dose rate of 128 cGy/min on day 0, the day of transplantation. Donor bone marrow (BM) cells (1 × 107) mixed with spleen cells (5 × 107) were given as a single intravenous injection through the tail vein. Donor immunization was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 2 × 107splenocytes on day −14.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

MHC class 1 (H2Db)/peptide (B6dom1) tetramers were produced as previously described.20 The following antibodies were obtained from PharMingen (San Diego, CA): fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled anti-Vβ12 T-cell receptor (MR11-1), FITC-labeled anti-CD44 (Pgp-1, Ly-24), phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD90.2 (Thy-1.2), allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD4 (RM4-5), and anti-CD8 (53-6.7). Evaluation of apoptotic cells was performed by staining with FITC–Annexin V (PharMingen) as described.23Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Differences between group means were tested using Student t test.

Cytotoxicity assays

Direct cytotoxic activity was assessed by measuring [3H]thymidine release from EL4 target cells as described by Barry et al.24 Effectors were splenocytes harvested on day 15 after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) and enriched in CD8 T cells by depletion of CD4 and B cells using anti-CD4 and anti-B220 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).

Results

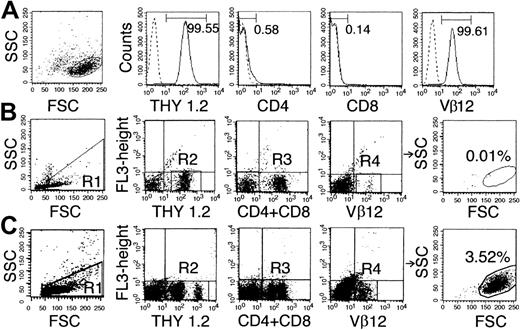

Phenotype of EL4 cells

EL4 cells were observed in vivo by staining with antibodies against Thy1.2, T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ12, CD4, and CD8 because we found that EL4 cells were uniformly Thy1.2+ TCR Vβ12+ CD4−CD8− (Figure1A) and that the proportion of cells with this phenotype in the BM, lymph nodes, and spleen of normal mice was 0.02% or less (Figure 1B).

Phenotype of EL4 cells.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of in vitro–grown EL4 cells stained with monoclonal antibody against Thy1.2, CD4, CD8, and TCR Vβ12. Numbers in graphs correspond to the percentage of positive cells. (B) Negative control showing the virtual absence (0.01%) of Thy1.2+CD4−CD8−Vβ12+cells in normal B10 splenocytes. (C) Detection of cells with the EL4 phenotype (3.52%) in the spleen of a B10 mouse 15 days after injection of 105 EL4. In panels B and C, cells in R1 were stained with antibodies against Thy1.2 (R2), CD4, and CD8 (R3) and Vβ12 (R4). Cells present in R1 + R2 + R3 + R4 are depicted in the rightmost panels.

Phenotype of EL4 cells.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of in vitro–grown EL4 cells stained with monoclonal antibody against Thy1.2, CD4, CD8, and TCR Vβ12. Numbers in graphs correspond to the percentage of positive cells. (B) Negative control showing the virtual absence (0.01%) of Thy1.2+CD4−CD8−Vβ12+cells in normal B10 splenocytes. (C) Detection of cells with the EL4 phenotype (3.52%) in the spleen of a B10 mouse 15 days after injection of 105 EL4. In panels B and C, cells in R1 were stained with antibodies against Thy1.2 (R2), CD4, and CD8 (R3) and Vβ12 (R4). Cells present in R1 + R2 + R3 + R4 are depicted in the rightmost panels.

Expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells following intravenous injection of EL4 cells into naive and preimmunized mice

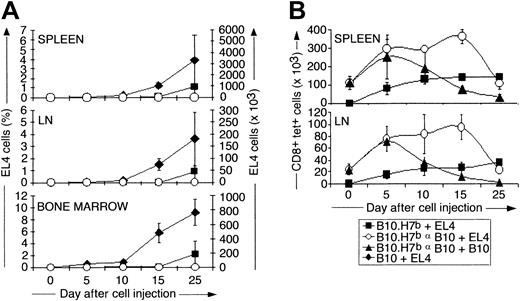

B6dom1 (H7a) is expressed by EL4 and B10 cells but not by congenic B10.H7b cells. We first assessed the accumulation of EL4 cells from day 0 to 25 after intravenous injection in naive B10 and B10.H7b mice and in preimmunized B10.H7b mice (Figure 1C). In this and all further experiments, preimmunization was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 2 × 107 B10 splenocytes on day −14. Previous studies have shown that after the intravenous injection of 5 × 105 EL4 cells, the cancer death rates in naive B10, naive B10.H7b, and preimmunized B10.H7bmice were 100%, 80%, and 0%, respectively. The median time to death was day 25 for B10 mice and day 36 for naive B10.H7bmice.20 After day 10, EL4 expanded rapidly and at a similar pace in the BM, lymph nodes, and spleen of B10 mice (Figure2A). EL4 cells were detected only later and in lesser amounts in naive B10.H7b mice and were undetectable in immunized B10.H7b mice. Thus, anti-B6dom1–specific T-cell responses by naive mice can to some extent mitigate the expansion rate of EL4 cells, but only in B6dom1-immune mice is the accumulation of EL4 cells totally prevented.

Analysis of the expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells after intravenous injection of EL4 cells into naive and immunized mice.

B10 and B10.H7b mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 EL4 cells or B10 splenocytes on day 0 (+EL4 and +B10, respectively). B10.H7b recipients were either naive or preimmunized with 2 × 107 B10 splenocytes (αB10) intraperitoneally on day −14. (A) Number of EL4 cells (Thy1.2+CD4−CD8−Vβ12+) present in the spleen, inguinal lymph nodes, and BM (2 tibiae and femurs). Naive versus preimmunized mice: P = .04 for spleen and lymph node, and P = .007 for bone marrow on day 25. (B) Number of B6dom1-specific T cells (CD8+tet+) in the spleen and inguinal lymph nodes. Primed mice challenged with EL4 versus B10 cells:P = .004 on day 15. Results are depicted as the mean ± SD of 3 mice per group.

Analysis of the expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells after intravenous injection of EL4 cells into naive and immunized mice.

B10 and B10.H7b mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 EL4 cells or B10 splenocytes on day 0 (+EL4 and +B10, respectively). B10.H7b recipients were either naive or preimmunized with 2 × 107 B10 splenocytes (αB10) intraperitoneally on day −14. (A) Number of EL4 cells (Thy1.2+CD4−CD8−Vβ12+) present in the spleen, inguinal lymph nodes, and BM (2 tibiae and femurs). Naive versus preimmunized mice: P = .04 for spleen and lymph node, and P = .007 for bone marrow on day 25. (B) Number of B6dom1-specific T cells (CD8+tet+) in the spleen and inguinal lymph nodes. Primed mice challenged with EL4 versus B10 cells:P = .004 on day 15. Results are depicted as the mean ± SD of 3 mice per group.

We estimated the number of B6dom1-specific CD8 T cells at the same time points in naive and preimmunized B10.H7b mice challenged with EL4 cells (Figure 2B). In addition, a control group of preimmunized mice was reinjected with B10 cells to evaluate whether the type of cells used for challenge, neoplastic or not, influenced the T-cell response. In naive B10.H7b mice injected with EL4 cells, numbers of B6dom1-specific T cells increased slowly in the spleen and lymph nodes during the first 10 days, then remained relatively unchanged to day 25. This kinetics of expansion of antigen-specific CD8 T cells in naive mice was unlike the brisk expansion followed by rapid decline after days 5 to 10 typically seen during the course of acute viral and bacterial infections.25 Expansion of B6dom1-specific T cells was more rapid and extensive in preimmunized than in naive mice. Interestingly, its duration was considerably prolonged when the cells injected on day 0 were EL4 rather than B10. The latter point indicates that the elimination of rapidly proliferating neoplastic cells is more demanding for the immune system than the elimination of normal cells.

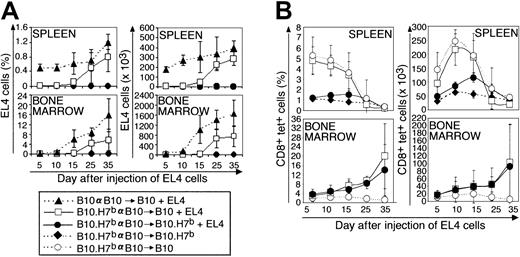

Expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells after adoptive T-cell transfer in B10 and B10.H7bhosts

In the next series of experiments, BM cells and splenocytes from preimmunized B10.H7b donors were injected into irradiated B10 or B10.H7b hosts to address the following questions: (1) Can adoptively transferred T cells respond to EL4 cells with the same efficacy as do normal mouse T cells? (2) How does the tissue distribution of the target antigen, here B6dom1, influence the outcome of adoptive immunotherapy? Previous studies have shown that all B10 recipients of a B10 graft die of leukemia by day 40; in contrast, when the donor is a B10.H7b mouse preimmunized against B6dom1, the leukemia death rate is 40% and 0% for B10 and B10.H7b recipients, respectively.20Consistent with survival data, EL4 cells expanded rapidly in recipients of B10 cells and accumulated more slowly and to lower levels in B10 recipients of a preimmunized B10.H7b donor (Figure3A; P < .05). In contrast, EL4 cells remained undetectable in B10.H7b recipients of a preimmunized B10.H7b donor (P < .005; B10.H7b vs B10 recipients). Of note, the geography of EL4 cell accumulation in irradiated recipients (Figure 3A) was different from the geography observed in mice that did not undergo transplantation (Figure 2A). This can be illustrated by comparing B10 mice that did not undergo transplantation with irradiated B10 recipients of B10 transplanted allogeneic hematopoietic cells. On day 25, the absolute number of EL4 cells in the group that underwent transplantation compared with the group that did not was increased 2 times in BM but decreased 10 times in spleen (Figures 2A, 3A). Lymph nodes of recipients of transplanted cells were too hypocellular for study.

Analysis of the expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells following adoptive T-cell transfer in B10 and B10.H7b hosts.

BM cells (107) and spleen cells (5 × 107) from donors preimmunized with B10 splenocytes on day −14 were injected into irradiated (10 Gy) B10 or B10.H7b recipients on day 0. Some groups were injected with 5 × 105 EL4 cells on day +1 (+EL4). (A) Proportion and absolute number of EL4 cells found in recipient spleen and BM (2 tibiae and femurs). (B) Proportion and absolute number of B6dom1-specific T cells in recipient spleen and BM. Results are depicted as the mean ± SD of 3 mice per group.

Analysis of the expansion kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells and EL4 cells following adoptive T-cell transfer in B10 and B10.H7b hosts.

BM cells (107) and spleen cells (5 × 107) from donors preimmunized with B10 splenocytes on day −14 were injected into irradiated (10 Gy) B10 or B10.H7b recipients on day 0. Some groups were injected with 5 × 105 EL4 cells on day +1 (+EL4). (A) Proportion and absolute number of EL4 cells found in recipient spleen and BM (2 tibiae and femurs). (B) Proportion and absolute number of B6dom1-specific T cells in recipient spleen and BM. Results are depicted as the mean ± SD of 3 mice per group.

The key finding concerned the kinetics of B6dom1-specific T cells in B10 compared with B10.H7b recipients of B10.H7b donors preimmunized with B10 cells. In B10.H7b hosts injected with EL4 cells, the number of B6dom1-specific T cells in the spleen reached a peak of approximately 120 × 103 on day 15 and decreased progressively thereafter (Figure 3B). This was significantly (P < .05), though not exceedingly, superior to the levels observed in B10.H7b controls not receiving EL4 cells and in which the accumulation of B6dom1-specific T cells was attributed solely to homeostatic expansion. Strikingly, expansion of B6dom1-specific T cells was more rapid and extensive in B10 recipients, in which it reached a zenith of approximately 225 × 103/spleen on day 10 (P < .005). However, this accumulation decreased abruptly thereafter so that the number of B6dom1-specific T cells on day 25 was lower in B10 than in B10.H7b recipients.

Because the BM was a preferential site of growth of EL4 cells in mice that underwent irradiation and transplantation, we estimated BM infiltration by B6dom1-specific T cells. Accumulation of tetramer+ cells in the BM did not follow the same course as in the spleen (Figure 3B). Indeed, BM infiltration by B6dom1-specific T cells was seen only in recipients injected with EL4 cells. In the absence of EL4 cells, no accumulation of tetramer+ cells was found in B10 hosts even though B6dom1 expression is practically ubiquitous in these mice. Consistent with this, the genotype of the EL4 injected hosts, B10 versus B10.H7b (that is, bearing B6dom1 or not on nonneoplastic cells), had no influence on the number of B6dom1-specific T cells found in the BM. Moreover, though it started later than it did in the spleen, the accumulation of tetramer+ T cells in the BM increased steadily over the observation period so that by day 35, tetramer+ T cells were more numerous in the BM than in the spleen.

We next assessed by Annexin V staining the rate of apoptosis because it determines, in conjunction with the mitotic rate, the kinetics of T-cell accumulation. At all time points, the proportion of apoptotic B6dom1 tetramer+ T cells showed a dramatic increase in B10 compared with B10.H7b hosts (Figure4A). Thus, on day 15, approximately 34% of tetramer+ CD8 T cells were Annexin V+ in B10 hosts, but the rate was only approximately 10% in B10.H7bhosts (P < .005). B10 recipients also presented a mild but significant increase in the proportion of Annexin V+elements among tetramer− CD8 T cells (P = .01); this is consistent with the previous demonstration that host-reactive CD8 T cells that undergo activation-induced cell death (AICD) also induce bystander apoptosis of other (non–host-reactive) donor-derived T cells.23Activated T cells down-modulate their TCR. The extent of this down-modulation is correlated with the strength of the TCR signal and is most pronounced in T cells confronted with a highly abundant epitope.25 In accordance with this, mean fluorescence intensity of B6dom1 tetramer labeling was remarkably decreased in B10 compared with B10.H7b hosts (Figure 4B); this was true for both Annexin V–positive and –negative tetramer+ T cells (Table 1).

Apoptosis rate and cytotoxic activity of B6dom1-specific T cells in B10 versus B10.H7b hosts.

BM cells (107) and spleen cells (5 × 107) from B10.H7b donors preimmunized with B10 splenocytes on day −14 were injected into irradiated (10 Gy) B10 or B10.H7b recipients on day 0. Recipients were injected with 5 × 104 EL4 cells on day +1. (A) Proportion of Annexin V+ cells among tetramer+ and tetramer− CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7brecipients. (B) Tetramer staining of CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7b mice; numbers indicate the mean fluorescence intensity of tetramer+ cells. (C) Direct cytotoxic activity of CD8 T cells harvested on day 15 after AHCT. Spleen CD8 T cells were enriched by negative depletion of B and CD4 lymphocytes and were cultured for 6 hours at various effector-to-target ratios with [3H]thymidine–labeled EL4 cells (3 mice per group).

Apoptosis rate and cytotoxic activity of B6dom1-specific T cells in B10 versus B10.H7b hosts.

BM cells (107) and spleen cells (5 × 107) from B10.H7b donors preimmunized with B10 splenocytes on day −14 were injected into irradiated (10 Gy) B10 or B10.H7b recipients on day 0. Recipients were injected with 5 × 104 EL4 cells on day +1. (A) Proportion of Annexin V+ cells among tetramer+ and tetramer− CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7brecipients. (B) Tetramer staining of CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7b mice; numbers indicate the mean fluorescence intensity of tetramer+ cells. (C) Direct cytotoxic activity of CD8 T cells harvested on day 15 after AHCT. Spleen CD8 T cells were enriched by negative depletion of B and CD4 lymphocytes and were cultured for 6 hours at various effector-to-target ratios with [3H]thymidine–labeled EL4 cells (3 mice per group).

Mean tetramer staining intensity of Annexin V+and Annexin V− tetramer+ CD8 T cells

| Recipient . | Annexin V . | Days after injection of EL4 cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | ||

| B10 | Positive | 61 ± 9 | 57 ± 8 | 43 ± 3 |

| Negative | 104 ± 9 | 74 ± 4 | 70 ± 7 | |

| B10.H7b | Positive | 81 ± 15 | 105 ± 15 | 67 ± 8 |

| Negative | 193 ± 60 | 150 ± 38 | 104 ± 8 | |

| Recipient . | Annexin V . | Days after injection of EL4 cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 . | 10 . | 15 . | ||

| B10 | Positive | 61 ± 9 | 57 ± 8 | 43 ± 3 |

| Negative | 104 ± 9 | 74 ± 4 | 70 ± 7 | |

| B10.H7b | Positive | 81 ± 15 | 105 ± 15 | 67 ± 8 |

| Negative | 193 ± 60 | 150 ± 38 | 104 ± 8 | |

Antigen-driven T-cell expansion is not synonymous with protective immunity. Accumulating evidence indicates that antigen-specific CD8 T cells may expand considerably in vivo yet show defective effector activity.26 We therefore compared the cytotoxic activity of freshly harvested CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7brecipients. On day 15, CD8 splenocytes were directly assayed for cytotoxic activity ([3H]thymidine release) against EL4 cells (Figure 4C). The nature of the host had a dramatic influence on anti-EL4 effector function: strong cytotoxicity was observed with CD8 T cells from B10.H7b hosts but not from B10 hosts (P = .02).

Discussion

The crucial point emerging from this work is that the tissue distribution of target antigen, here B6dom1, has a profound influence on the outcome of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy. When B6dom1-primed T cells were injected into recipients (B10.H7b) in which B6dom1 was present only on EL4 cancer cells, B6dom1-specific T cells expanded to reach a peak in host spleen on day 15 and progressively declined thereafter, displayed direct cytotoxic activity, and completely eliminated EL4 cells. In contrast, when B6dom1 was ubiquitously expressed (B10 hosts), B6dom1-specific T cells proliferated more extensively but showed poor effector function, underwent major AICD, and were less effective at eradicating EL4 cells. These data explain why the EL4 cure rate is 100% in B10.H7b hosts but only 60% in B10 hosts.20 Moreover, this correlation between antigen load and the fate of injected T cells is strikingly similar to what is observed with T-cell response to the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.25 Thus, the risk for AICD after adoptive immunotherapy must be taken into account whether the target antigen is a viral epitope or an endogenous host MHC class 1–associated peptide (the immunodominant B6dom1 MiHA in our model). As a corollary, our finding that overstimulated donor-derived T cells can become dysfunctional implies that assessing the level of protection afforded by adoptive cancer immunotherapy will probably require combined phenotypic and functional analyses of antigen-specific T cells.

Our data demonstrate that in cancer treatment, the pitfalls inherent in adoptive immunotherapy differ from those associated with vaccination. Thus, following vaccination with tumor-associated antigens, the strength of the immune response increases in parallel with antigen dose, and AICD is not an issue.27 Because tumor-associated antigens elicit mainly low-avidity T cells, the efficacy of tumor vaccines is limited by poor immunogenicity rather than AICD. The notion that AICD is a possible outcome of adoptive cancer immunotherapy has several implications. Thus, the fact that alloreactive T cells can become hyporesponsive and disappear subsequent to AICD would explain a well-recognized paradox: malignancies relapsing after AHCT remain sensitive to donor anti-host CTLs in vitro and can be successfully treated with reinjection of lymphocytes from the original donor.14,17,28 Based on our work, we speculate that most leukemic relapses are caused by the disappearance of effector/memory T cells rather than by the emergence of resistant neoplastic cells. How long adoptively transferred T cells must persist to achieve cancer cure has yet to be determined.28,29 Nevertheless, because some cancers relapse months to years after AHCT, continuous remission may require long-term persistence of memory T cells. Further studies will be required to assess the expression profile of immunodominant human MiHAs and to what extent these antigens can induce AICD of adoptively transferred T cells. One inference from the present work is that when adoptive immunotherapy is targeted to an abundant and widely expressed antigen, strategies will have to be developed to prolong the survival of donor T cells. In additional studies we intend to evaluate whether this might be achieved by increasing the supply of cytokines such as interleukin-7 (IL-7) or IL-15.30-33 When possible, it may be preferable to target epitopes with a limited tissue distribution.

Although EL4 cells accumulated chiefly in the secondary lymphoid organs in mice that did not undergo transplantation, the main site of EL4 cell growth was the BM in mice that underwent transplantation and irradiation. A plausible explanation is that because irradiation induces damage to the stroma of secondary lymphoid organs (for example, microvascular occlusions) that impede the homing of lymphoid cells to the lymph nodes,34 EL4 cells seed and proliferate in the BM of irradiated hosts. We therefore asked whether significant numbers of adoptively transferred B6dom1-specific T cells would be able to reach the site harboring the greatest cancer burden, the BM. The key findings in BM were that B6dom1-specific T cells accumulated to unexpectedly high levels, with kinetics entirely different from kinetics in the spleen, and that, surprisingly, this accumulation was EL4 dependent. It has been shown that after viral infection, effector/memory CD8 T cells emigrate from secondary lymphoid organs and disseminate widely in nonlymphoid organs, such as the BM, in which the virus does not replicate.35,36 Could the presence of high numbers of B6dom1-specific T cells in the BM of irradiated leukemic recipients result solely from random migration of effector/memory T cells? Two findings strongly argue against this. First, when T cells primed in secondary lymphoid organs accumulate in other organs simply because of random dissemination, the kinetics of T-cell accumulation and disappearance is similar in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs.36,37 This was clearly not the case in our study. Here the accumulation of B6dom1-specific T cells in the BM started later but lasted longer than in the spleen (Figure 3B). Second, and of special significance, though B6dom1 is expressed by hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells of all tissues and organs of B10 mice,20 21 only when these recipients were injected with EL4 cells did B6dom1-specific T cells accumulate in the BM (Figure 3B). This is notably different from what was seen in the spleen, where the expansion of B6dom1-specific T cells was influenced more by the presence of B6dom1 on normal host cells than by the presence or absence of EL4 cells. These data strongly suggest that T cells expanded in the BM because EL4 cells, which accumulated chiefly there, induced in situ proliferation of B6dom1-specific T cells that had migrated to the BM.

In the BM of leukemic mice that underwent transplantation, the number of B6dom1-specific T cells increased over the entire observation period (35 days) without evidence of attrition. This suggests that after adoptive immunotherapy, the primary sites of tumor growth (rather than the classical secondary lymphoid organs) are the main repositories of effector/memory T cells. It will be important to determine the cause of this. Indeed, assuming its generality, this paradigm would imply that local monitoring of the immune response at the site of tumor growth may be mandatory for a meaningful assessment of the efficacy of adoptive immunotherapy.

We thank Marie-Ève Blais and Sylvie Brochu for insightful comments and Ms J. Kashul for editorial assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 22, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1032.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Canadian Network for Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics of Cancer and Chronic Viral Diseases (CANVAC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Claude Perreault, Guy-Bernier Research Center, Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, 5415 de l'Assomption Blvd, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H1T 2M4; e-mail:c.perreault@videotron.ca.

![Fig. 4. Apoptosis rate and cytotoxic activity of B6dom1-specific T cells in B10 versus B10.H7b hosts. / BM cells (107) and spleen cells (5 × 107) from B10.H7b donors preimmunized with B10 splenocytes on day −14 were injected into irradiated (10 Gy) B10 or B10.H7b recipients on day 0. Recipients were injected with 5 × 104 EL4 cells on day +1. (A) Proportion of Annexin V+ cells among tetramer+ and tetramer− CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7brecipients. (B) Tetramer staining of CD8 T cells from B10 and B10.H7b mice; numbers indicate the mean fluorescence intensity of tetramer+ cells. (C) Direct cytotoxic activity of CD8 T cells harvested on day 15 after AHCT. Spleen CD8 T cells were enriched by negative depletion of B and CD4 lymphocytes and were cultured for 6 hours at various effector-to-target ratios with [3H]thymidine–labeled EL4 cells (3 mice per group).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/2/10.1182_blood-2002-04-1032/4/m_h80233707004.jpeg?Expires=1769164102&Signature=DZ2h7iVeMPQBO-b-TBYQTjXb9n9bz6gpb-zompgnvSaRhwsYb1iHLIvMj9~FMUq0INHLuFM9uZUN4XdE0d48D18~7~Gy9MpBo6h~xpH1IJGTh3Fglf2qraj--SepqcToG9ZYqrAXrkvsjqjNe~EY-nn~AiKTKCCWB7IFJam~vn3CLP~O0jYb5zAqemVmYWX6D-oWBnguwnsP9eFhnSrI7vH2PeBxWozWog-mx7ZdUqvNdO2-erUIsIofD7tZfCRubvVQaO5-WOQT-W~a0vht-6r8cGEoVP9DDCiVfusvO6uSs79m64MF7PbOZlaFhg18vCTyHkW1Oabb2UUXUywOWA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal