Abstract

Recent reports indicate a broad spectrum of antileukemic activity for arsenic trioxide (As2O3) due to its ability to induce apoptosis via intracellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Despite its potent apoptotic mechanism, As2O3 is not equally effective in all leukemic cells, which has prompted a search for agents enhancing As2O3 efficacy. Recently, evidence has been gathered that the polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) may sensitize tumor cells to ROS-inducing anticancer agents. The aim of our investigation was to evaluate whether DHA enhances As2O3-mediated apoptosis in As2O3-resistant HL-60 cells. While 1 μM As2O3 or 25 μM DHA reduced cell viability to 85.8% ± 2.9% and 69.2% ± 3.6%, combined treatment with As2O3 and DHA reduced viability to 13.0% ± 9.9% with a concomitant increase of apoptosis. Apoptotic cell death was preceded by collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, increased expression of proapoptotic B-cell lymphoma protein-2–associated X protein (Bax), and caspase-3 activation. Importantly, the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA was associated with increased production of intracellular ROS and toxic lipid peroxidation products and was abolished by the antioxidant vitamin E or when oleic acid (a nonperoxidizable fatty acid) was used in place of DHA. Intracellular ROS and toxic lipid peroxidation products most likely constitute the key mediators contributing to the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA. Our data provide the first evidence that DHA may help to extend the therapeutic spectrum of As2O3 and suggest that the combination of As2O3 and DHA could be more broadly applied in leukemia therapy.

Introduction

For centuries, arsenic compounds have been used empirically in the treatment of a wide variety of diseases.1-3 In the 1970s, arsenic trioxide (As2O3) was first introduced into the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) with remarkable clinical success. Clinical complete remission rates following As2O3 therapy were 65.6% to 84%, with approximately 30% of patients surviving more than 10 years. Of particular importance, As2O3 was found to be effective even in patients who relapsed after all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)–induced clinical remission. Moreover, in contrast to patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy, the vast majority of patients showed neither bone marrow depression nor other severe clinical side effects during As2O3 treatment.4-8

In vitro investigations in APL-derived NB-4 cells showed that clinically achievable concentrations of As2O3 (1 to 2 μM) induce apoptosis through a reactive oxygen species (ROS)–dependent pathway: Intracellularly accumulating ROS led to disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome c with consecutive activation of the caspase cascade, and, ultimately, to programmed cell death through apoptosis.9-11 Importantly, it has become evident that the apoptotic effect of As2O3 is not restricted to APL cells but can also be observed in other malignant cells in vitro, including non-APL acute myeloid leukemia cells, myeloma cells, and chronic myeloid leukemia cells, as well as various solid tumor cells.12-26 However, owing to their lower sensitivity, up to 10-fold higher concentrations of As2O3 are required to induce apoptosis in non-APL tumor cells, which is generally unacceptable in the clinic because of toxicity.11,27,28 As a consequence, both clinical use and efficacy of As2O3 have thus far been largely restricted to patients with APL.

In recent years, potential mechanisms to enhance the effects of As2O3 in As2O3-resistant tumor cells have therefore been elucidated, with the aim of extending the therapeutic spectrum of As2O3. Since the cellular glutathione (GSH) oxidation-reduction (redox) system modulates the growth-inhibitory and apoptotic effects of As2O3 with increasing levels of GSH conferring resistance to As2O3, attempts have been made to enhance the effects of As2O3 with the use of agents modulating the GSH redox system.12,29 Furthermore, we and others have shown that ascorbic acid may also synergize with the oxidative effects of As2O3 owing to its capacity to undergo intracellular autooxidation resulting in increased intracellular levels of ROS.17,29,30

Recently, some evidence has been gathered that the incorporation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), that is, fatty acids with more than 2 double bonds, into cellular membranes may sensitize tumor cells to ROS-inducing anticancer agents both in vitro and in vivo.31-36 The ability of PUFAs to undergo lipid peroxidation has been implicated as being of pivotal importance for this effect: In response to oxidative stress induced by ROS-inducing agents, PUFAs undergo free-radical chain reaction breakdown resulting in the formation of toxic lipid peroxidation products which, in turn, synergize with the ROS induced by the oxidative agent to induce tumor cell apoptosis.31 Conversely, incorporation of monounsaturated fatty acids into cellular membranes has been found to result in decreased lipid peroxidation, protecting cells from oxidative stress.37 Because of the enhancing effect of PUFAs, we hypothesized that the ω-3 PUFA docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which contains 6 double bonds (22:6n-3), might be suited to enhance As2O3 efficacy in As2O3-resistant tumor cells. To test our hypothesis, we used the acute myeloid leukemia cell line HL-60, which has been shown to be resistant to clinically achievable concentrations of 1 to 2 μM As2O3.29 To evaluate whether a possible enhancing effect of DHA was PUFA-specific and to define the potential relationship between cellular lipid peroxidation products and increased As2O3 toxicity, we also tested the effect of oleic acid, a nonperoxidizable ω-9 monounsaturated fatty acid (OA) (18:1n-9), on As2O3-mediated apoptosis. The aim of our investigation was to elucidate a possible enhancing effect of DHA and As2O3 in As2O3-resistant tumor cells in order to obtain initial preclinical evidence for the potential efficacy of As2O3/DHA combination therapy in malignancies intrinsically less sensitive to As2O3 monotherapy.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

As2O3, pure (99%) cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-DHA, cis-9-OA, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone, and dl-α-tocopherol (vitamin E) were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO). The 6-carboxy-2′,7′ dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Stock solutions of fatty acids (140 mM) were prepared in 99% ethanol, stored in oxygen-free light-protected vials at –70°C, and further diluted in complete growth medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) before use in such a way that the final concentration of ethanol was less than 0.07% (vol/vol). As2O3 was prepared as a 10 mM aqueous solution and further diluted in complete growth medium to the working concentration of 1 μM before use. Vitamin E was prepared as a 50 mM solution in ethanol and stored at 4°C. The working solution was prepared at a concentration of 20 μM with the use of growth medium.

Cell culture

HL-60, Jurkat, and Namalwa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Daudi and SH-1 cells were a kind gift from Dr M. Shehata, Department of Hematology, University Hospital Vienna (Austria). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with glutamax-I (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Inchinnan, Scotland), gentamicin (50 μg/mL), and 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Normal human skin fibroblasts CCD-32Sk (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection) were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Bio Whittaker, Verviers, Belgium), supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs) (a kind gift from Dr C. Brostjan, Surgical Research Laboratories, University Hospital Vienna, Austria) were cultured in EGM2-MV growth medium (Bio Whittaker). After written informed consent, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from 3 healthy donors with the use of Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient centrifugation. All cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Cell stocks were screened for mycoplasma species by means of the polymerase chain reaction method (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany).

In vitro cell viability assay

HL-60, Jurkat, SH-1, and Namalwa cells (2 × 104 per well) as well as Daudi cells (5 × 103 per well) were cultured in duplicate in 96-well flat-bottomed microplates in growth medium containing 1 μM As2O3 with or without 25 μM DHA or OA in a final volume of 200 μL per well. Cells grown in the presence of medium alone, 25 μM DHA, or 25 μM OA were used as controls. To evaluate the blocking effect of vitamin E, one set of plates received 20 μM vitamin E simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. Human skin fibroblasts were seeded in duplicate in 96-well flat-bottomed microplates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in 200 μL growth medium. After 24 hours, growth medium containing either As2O3, DHA, or a combination of As2O3 and DHA was added. HMECs were seeded in duplicate in 96-well fibronectin-coated microplates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. Cells were grown to confluence and treated as described. Following treatment, cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric Easy for You Assay Kit (EZ4U; Biomedica, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer′s instructions, and absorbance at 450 nm was measured spectrophotometrically by means of a Dynatech Microplate Reader 5000 (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, VA). PBMCs (3 × 105/mL) were cultured in growth medium containing either As2O3, DHA, or a combination of As2O3 and DHA for 48 hours. Thereafter, viability of PBMCs was determined by means of trypan blue exclusion.

Apoptosis assays

Quantification of apoptotic cells was performed by bivariate annexin V/propidium iodide flow cytometry with the use of the Apoptosis Detection Kit from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, MD). The assay was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometry with an Epics Elite XL-MCL flow cytometer and EXPO 32 software (Coulter Immunotech, Marseilles, France). In addition, for analysis of cells with hypodiploid DNA, cells were fixed with ice-cold 80% ethanol for 30 minutes at a cell density of 1 × 106/mL. Subsequently, the cells were stained with a staining solution containing Triton-X 100 (0.1%), 0.1 mM EDTA(Na)2 (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid–(Na)2), 100 μg/mL RNase, and 50 μg/mL propidium iodide. Finally, DNA content of the cells was measured by means of flow cytometry.

Detection of intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS were detected by means of an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe, DCFH-DA. Before and after treatment with 1 μM As2O3, alone or in combination with 25 μM fatty acids, cells (1 × 105/mL) were incubated with 20 μM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes, as described previously.38 After 12 hours of treatment, the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation in cell cultures was measured by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay, which was slightly modified to achieve reproducible results: cells at 1 × 105/mL were seeded in flasks (25 cm2) and treated with As2O3, fatty acids or a combination of As2O3 and fatty acids for 18 hours. To evaluate the blocking effect of vitamin E, one set of flasks received 20 μM vitamin E simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. Thereafter, the cells were washed and resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS. To avoid lipid peroxidation during the assay, butylated hydroxytoluene (0.01% [vol/vol] percentage of a 2% solution in ethanol) and EDTA (final concentration, 1 mM) were added to the sample prior to precipitation with 1 mL TCA-TBA-HCl reagent (15% [wt/vol] TCA [trichloroacetic acid], 0.375% [wt/vol] TBA, and 0.25 N HCl). Subsequently, the samples were heated in a boiling water bath for 15 minutes and centrifuged, and absorbance of the supernatant was measured spectrophotometrically at 535 and 600 nm. Absorbance was converted to picomoles of TBA-reactive substances (TBARS) per 1 × 106 cells.

Assessment of changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

To evaluate Δψm, exponentially growing cells (1 × 105/mL) were incubated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM fatty acids, or their combination for 18 hours. Following treatment, the cells were labeled with DiOC6 (40 nM in culture medium) at 37°C for 30 minutes. After washing in PBS, cellular uptake of DiOC6 was analyzed by flow cytometry. Control experiments were performed in the presence of 50 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone, an uncoupling agent that abolishes the Δψm, for 30 minutes at 37°C.

Flow cytometric evaluation of Bcl-2 and Bax protein

Following treatment, 1 × 106 cells were fixed and permeabilized by the commercially available Fix and Perm Kit (An-der-Grub, Kaumberg, Austria) to allow for cytoplasmic staining using a monoclonal mouse antihuman B-cell lymphoma protein-2–associated X protein (Bax), antibody (clone 4F11; Coulter Immunotech), followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated secondary antibody (An-der-Grub) to detect expression of Bax. For detection of B-cell lymphoma protein-2 (Bcl-2) expression, a FITC-conjugated monoclonal mouse antihuman Bcl-2 antibody was used (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). After washing, the cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS containing 0.5% formaldehyde and subjected to flow cytometric analysis.

Western blot analysis

After 24 hours of treatment with As2O3, DHA, or the combination of both substances, cell extracts were prepared by lysing the cells in TEK-T lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane], 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, and 0.3% Triton, pH 7.9). For detection of caspase-3, 20 μg cell extract was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with bovine serum albumin, the membrane was incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti–caspase-3 antibody (BD Biosciences, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) followed by a horseradish peroxidase–linked secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). To assure equal protein loading, a similar experiment was performed with a monoclonal anti–β-actin antibody (Sigma Chemical) as internal control. The immunocomplexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Results

DHA markedly reduces viability of HL-60 cells when combined with As2O3

First, we tested the effects of As2O3 and the PUFA DHA (22:6n-3), both separately and in combination, on the viability of As2O3-resistant HL-60 cells. Figure 1 shows that after HL-60 cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3 or 25 μM DHA alone, cell viability was moderately reduced to 85.8% ± 2.9% and 69.2% ± 3.6% of control, respectively. However, if the cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination, a nearly 90% reduction of cell viability to 13.0% ± 9.9% of control was observed. In contrast, if the cells were treated with 25 μM of the monounsaturated fatty acid OA (18:1n-9) or the combination of 25 μM OA and 1 μM As2O3, no reduction of cell viability was observed. To elucidate the time point at which As2O3 and DHA start to exert their cytotoxic effect on HL-60 cells, we additionally monitored cell viability after 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours of incubation: While cell viability remained largely unchanged up to 12 hours, a marked reduction of viability was observed after 24 hours of incubation with As2O3 and DHA, indicating that As2O3 and DHA already exert their cytotoxic effect after 24 hours of treatment (data not shown). To test whether the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA was specific for malignant cells, we also tested normal human skin fibroblasts, HMECs, and PBMCs obtained from 3 healthy donors. Importantly, in contrast to HL-60 cells, none of the normal cells tested showed an enhancing effect of DHA on As2O3-mediated cytotoxicity (Table 1).

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation [SD]) of 3 independent experiments.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation [SD]) of 3 independent experiments.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of normal cells

. | Viability, % . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type . | As2O3 . | DHA . | As2O3 and DHA . | ||

| Fibroblasts | 100 ± 3.5 | 100 ± 2.7 | 100 ± 2.6 | ||

| HMECs | 95 ± 6.3 | 91 ± 6.0 | 100 ± 4.8 | ||

| PBMCs | |||||

| Donor 1 | 92 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Donor 2 | 100 | 100 | 96 | ||

| Donor 3 | 78 | 87 | 78 | ||

. | Viability, % . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type . | As2O3 . | DHA . | As2O3 and DHA . | ||

| Fibroblasts | 100 ± 3.5 | 100 ± 2.7 | 100 ± 2.6 | ||

| HMECs | 95 ± 6.3 | 91 ± 6.0 | 100 ± 4.8 | ||

| PBMCs | |||||

| Donor 1 | 92 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Donor 2 | 100 | 100 | 96 | ||

| Donor 3 | 78 | 87 | 78 | ||

Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay (fibroblasts, HMECs) or trypan blue exclusion (PBMCs). Values for fibroblasts and HMECs represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments.

DHA enhances As2O3-mediated apoptosis in HL-60 cells

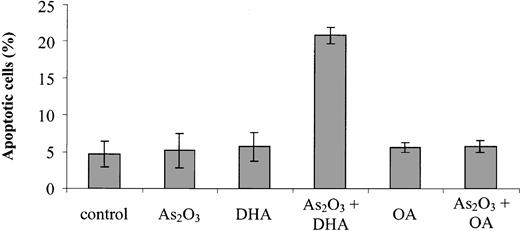

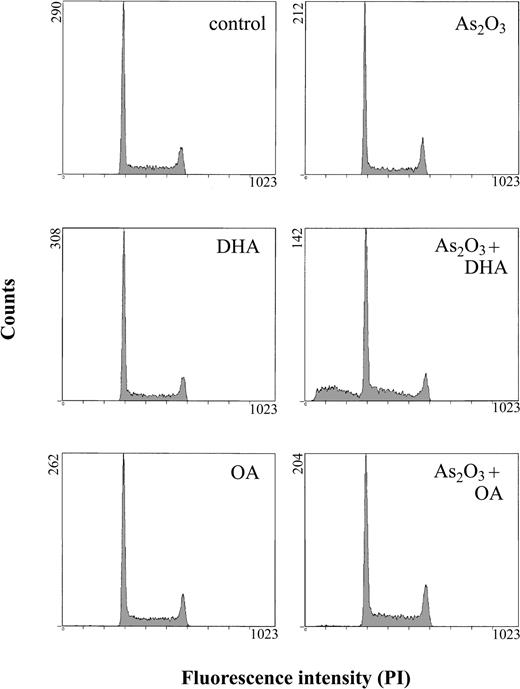

To evaluate whether the growth-inhibitory effect observed upon combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA was due to the induction of apoptosis, cells were treated for 24 hours and subsequently stained with annexin V/propidium iodide and analyzed by means of flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2, untreated cultures contained 4.7% ± 1.7% apoptotic cells. If either 1 μM As2O3 or 25 μM DHA was added to the cultures, the percentage of apoptotic cells remained largely unchanged, amounting to 5.2% ± 2.4% and 5.7% ± 1.9%, respectively. However, if the cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination, a 4-fold increase to 20.8% ± 1.1% apoptotic cells was observed. In contrast, if As2O3 was combined with the monounsaturated fatty acid OA, no enhancing effect was observed. To further confirm the induction of apoptosis by combined treatment with As2O3 and DHA, we also determined the percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA content following treatment with As2O3 and fatty acids, alone or in combination. As shown in Figure 3, only cultures treated with the combination of As2O3 and DHA contained a significant percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA, indicating that only combined treatment with As2O3 and DHA induced apoptosis in HL-60 cells whereas the combination of As2O3 and OA did not result in measurable changes of apoptotic rate.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on apoptosis of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated for 24 hours with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). After treatment, the cells were stained with annexin V/propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values are the mean (± SD) of 3 separate experiments.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on apoptosis of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated for 24 hours with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). After treatment, the cells were stained with annexin V/propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values are the mean (± SD) of 3 separate experiments.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the cell-cycle status and apoptosis. Cells were treated for 24 hours with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Thereafter, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI), and the percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA content, representing the proportion of apoptotic cells, was determined by means of flow cytometry.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the cell-cycle status and apoptosis. Cells were treated for 24 hours with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Thereafter, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI), and the percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA content, representing the proportion of apoptotic cells, was determined by means of flow cytometry.

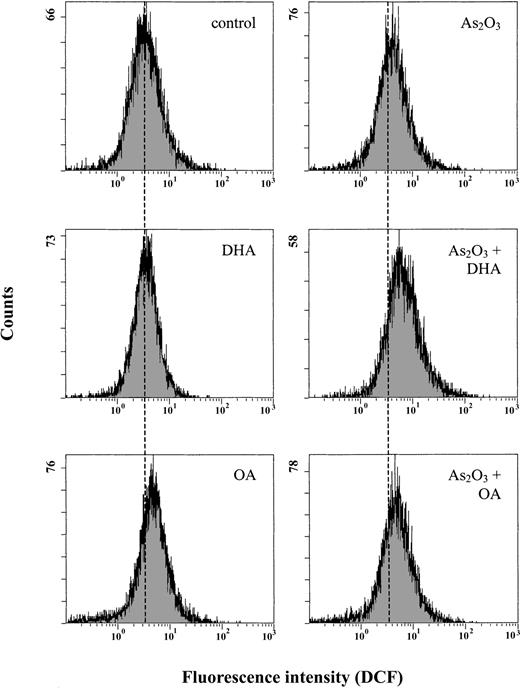

Combined treatment with As2O3 and DHA results in increased intracellular concentrations of ROS

Since As2O3 is known to act via induction of intracellular ROS, we subsequently determined the intracellular ROS content after 12 hours of treatment using the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA, which is oxidized to DCF in the presence of ROS. Figure 4 shows that treatment of the cells with 1 μM As2O3 alone increased mean DCF fluorescence only moderately, from 4.9 to 5.7, whereas combined treatment of the cells with As2O3 and DHA led to an approximately 2-fold increase of mean DCF fluorescence to 9.5. In contrast, if As2O3 was combined with the monounsaturated fatty acid OA, the mean DCF fluorescence remained largely constant at 6.0, equaling the amount of intracellular ROS generated upon treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 alone.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on intracellular accumulation of ROS in HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 12 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Intracellular ROS were measured by flow cytometry using an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe, DCFH-DA, which is oxidized to DCF in the presence of ROS. For improved illustration, a guidance line (dotted line) has been drawn through histograms to be compared.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on intracellular accumulation of ROS in HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 12 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Intracellular ROS were measured by flow cytometry using an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe, DCFH-DA, which is oxidized to DCF in the presence of ROS. For improved illustration, a guidance line (dotted line) has been drawn through histograms to be compared.

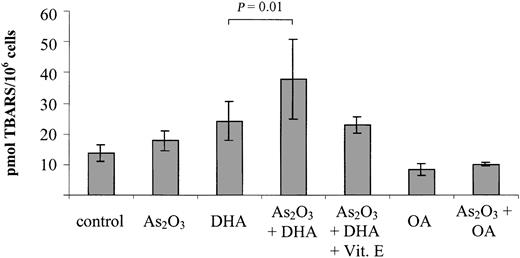

The combination of As2O3 and DHA results in significantly increased intracellular lipid peroxidation

To elucidate the possible involvement of lipid peroxidation products in the induction of growth inhibition/apoptosis by As2O3 and DHA, we further investigated the intracellular TBARS content following 18 hours of treatment with As2O3 and DHA, alone and in combination. As a control, we determined the intracellular TBARS content upon combined treatment of As2O3 with the monounsaturated, nonperoxidizable fatty acid OA. As shown in Figure 5, DHA alone increased intracellular TBARS from 13.8 ± 2.8 pmol/106 cells to 24.2 ± 6.3 pmol/106 cells, suggesting that lipid peroxidation was taking place within the cells. However, if As2O3 and DHA were combined, a further 50% increase of intracellular TBARS to 37.9 ± 13.1 pmol/106 cells was observed (P = .01). In contrast to DHA, neither OA alone nor the combination of OA and As2O3 led to any appreciable increase of intracellular TBARS in comparison with untreated controls.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on lipid peroxidation, as determined by intracellular TBARS content. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 18 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). To demonstrate the blocking effect of the antioxidant vitamin E, one set of cultures received 20 μM vitamin E simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. After treatment, the cells were harvested and analyzed by means of the thiobarbituric acid assay. Values represent the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments and are expressed as picomoles of TBARS per 1 × 106 cells. Statistical comparison of DHA- and As2O3/DHA-treated cultures was performed by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post-hoc analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on lipid peroxidation, as determined by intracellular TBARS content. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 18 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). To demonstrate the blocking effect of the antioxidant vitamin E, one set of cultures received 20 μM vitamin E simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. After treatment, the cells were harvested and analyzed by means of the thiobarbituric acid assay. Values represent the mean ± SD of 6 independent experiments and are expressed as picomoles of TBARS per 1 × 106 cells. Statistical comparison of DHA- and As2O3/DHA-treated cultures was performed by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post-hoc analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

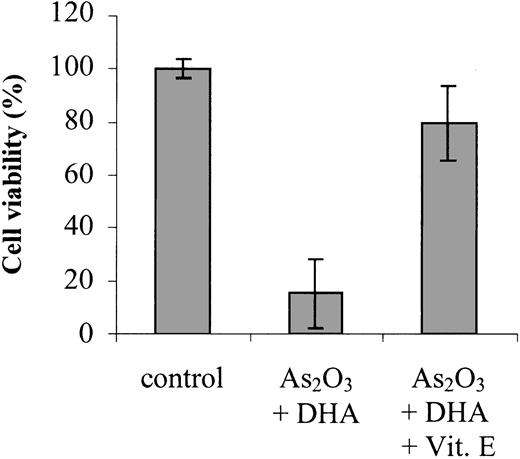

Vitamin E reduces DHA/As2O3-mediated lipid peroxidation and growth inhition

To confirm that enhanced lipid peroxidation is contributing to the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA on cell viability and apoptosis, we studied the ability of the antioxidant vitamin E to counteract the combination of As2O3 and DHA when added to the cultures simultaneously. As shown in Figure 5, addition of 20 μM vitamin E reduced DHA/As2O3-mediated intracellular TBARS by approximately 50%, from 37.9 ± 13.1 pmol/106 cells to 22.9 ± 2.6 pmol/106 cells. Importantly, it also reduced the combined deleterious effect of As2O3 and DHA on cell viability by approximately 80%, suggesting that, along with increased ROS production, enhanced lipid peroxidation of supplemented DHA molecules may constitute a crucial event contributing to the enhancement of As2O3 cytotoxicity by DHA (Figure 6).

Effects of vitamin E on As2O3/DHA-mediated cytotoxicity. Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination or left untreated (control). To demonstrate the blocking effect of vitamin E on As2O3/DHA-mediated cytotoxicity, 20 μM vitamin E was added to the cultures simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments.

Effects of vitamin E on As2O3/DHA-mediated cytotoxicity. Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination or left untreated (control). To demonstrate the blocking effect of vitamin E on As2O3/DHA-mediated cytotoxicity, 20 μM vitamin E was added to the cultures simultaneously with As2O3 and DHA. Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments.

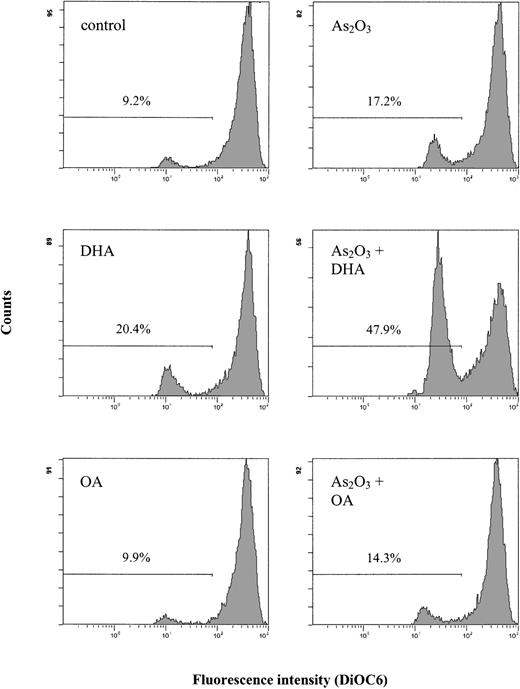

Combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA is associated with a reduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential

It is well known that an increase in intracellular ROS/TBARS concentrations may lead to changes in the mitochondrial metabolism, with subsequent disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential. Since the disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential is a critical step occurring in cells undergoing apoptosis, we evaluated whether combined treatment with As2O3 and DHA had any effect on the mitochondrial membrane potential. Figure 7 shows that after 18 hours of treatment of HL-60 cells with 1 μM As2O3 or 25 μM DHA alone, no substantial changes of the mitochondrial membrane potential as determined by DiOC6 fluorescence were noted. However, if the cells were treated with As2O3 and DHA in combination, a marked increase of cells with reduced DiOC6 fluorescence was observed, indicating disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential in these cells. In contrast, no significant changes of the mitochondrial membrane potential were noted if HL-60 cells were treated with the combination of As2O3 and OA.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the mitochondrial membrane potential of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 18 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). To determine the mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were stained with DiOC6 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values represent percent of cells with reduced mitochondrial membrane potential.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the mitochondrial membrane potential of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 18 hours. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). To determine the mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were stained with DiOC6 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Values represent percent of cells with reduced mitochondrial membrane potential.

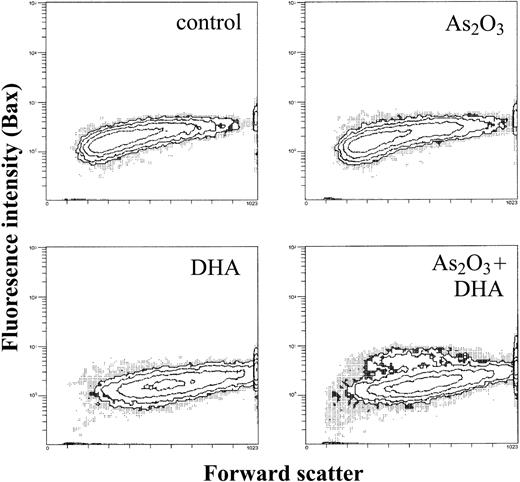

Proapoptotic Bax is upregulated in a subpopulation of As2O3/DHA-treated HL-60 cells

As a next step, we evaluated whether the decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential following treatment with As2O3 and DHA was associated with changes in the expression of mitochondrial proapoptotic and antiapoptotic molecules such as Bax and Bcl-2. Treated cells were permeabilized, stained with Bax or Bcl-2 antibodies, and analyzed by means of flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 8, combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA led to the appearance of a subpopulation of cells in which the mean fluorescence of proapoptotic Bax was increased from 1.9 to 5.1, whereas treatment of HL-60 cells with either As2O3 or DHA alone had no effect on intracellular Bax expression. In contrast, even combined treatment of the cells with As2O3 and DHA did not lead to any appreciable change in the intracellular expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 (data not shown).

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on intracellular Bax expression of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 24 hours. After treatment, cells were washed, permeabilized, and stained with an unconjugated monoclonal anti-Bax antibody, followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Data are expressed as contour plots of the forward scatter image (x-axis) plotted against Bax fluorescence intensity (y-axis) of a representative experiment.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on intracellular Bax expression of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 24 hours. After treatment, cells were washed, permeabilized, and stained with an unconjugated monoclonal anti-Bax antibody, followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Data are expressed as contour plots of the forward scatter image (x-axis) plotted against Bax fluorescence intensity (y-axis) of a representative experiment.

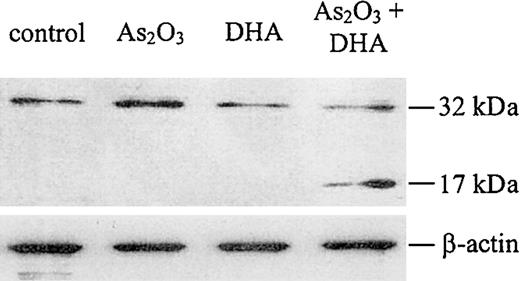

Caspase-3 is activated upon combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA

It is well established that the disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential may result in the activation of the caspase cascade, which has been shown to be a critical step in the apoptosis-signaling pathway. Therefore, to evaluate whether combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA was associated with caspase activation, we performed a Western blot for caspase-3. As shown in Figure 9, we found that caspase-3 was cleaved into its active fragment if HL-60 cells were treated with As2O3 and DHA in combination, whereas no activation of caspase-3 was observed if the cells were treated with either As2O3 or DHA alone.

Western blot analysis for caspase-3 protein. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 24 hours. After treatment, the cells were lysed and analyzed by Western blot, as described in “Materials and methods.” Upper panel: Caspase-3 protein. Note that the antihuman caspase-3 antibody used in our experiments recognizes both the inactive proenzyme of caspase-3 (32 kDa) and its cleaved active fragment (17 kDa). Lower panel: β-actin, as internal control to verify equal protein loading.

Western blot analysis for caspase-3 protein. Cells were treated with 1 μM As2O3, 25 μM DHA, or the combination of both substances for 24 hours. After treatment, the cells were lysed and analyzed by Western blot, as described in “Materials and methods.” Upper panel: Caspase-3 protein. Note that the antihuman caspase-3 antibody used in our experiments recognizes both the inactive proenzyme of caspase-3 (32 kDa) and its cleaved active fragment (17 kDa). Lower panel: β-actin, as internal control to verify equal protein loading.

The combined effect of As2O3 and DHA is also found in other hematologic malignancies

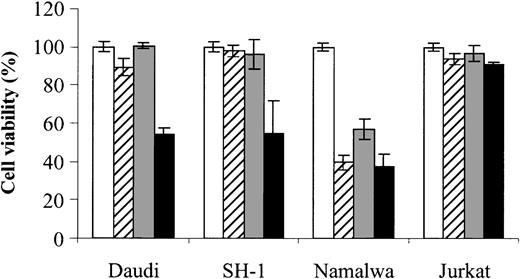

Finally, to assess whether the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA can also be observed in cells derived from other hematologic malignancies, we also tested Daudi (Burkitt lymphoma), SH-1 (hairy-cell leukemia), Namalwa (Burkitt lymphoma), and Jurkat (T-cell leukemia) cells. Notably, in 2 (Daudi and SH-1) of 4 cell lines tested, an enhancing effect of DHA on As2O3-mediated cytotoxicity could be demonstrated, indicating that the combined effect of As2O3 and DHAis not restricted to HL-60 cells. However, no enhancing effect was observed in Namalwa cells, which were already sensitive to either As2O3 or DHA alone, or in Jurkat cells, which were resistant even to the combination of As2O3 and DHA (Figure 10).

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of Daudi, SH-1, Namalwa, and Jurkat cells. Daudi (Burkitt lymphoma), SH-1 (hairy-cell leukemia), Namalwa (Burkitt lymphoma), and Jurkat (T-cell leukemia) cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3 (▨), 25 μM DHA (▦), or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination (▪). For comparison, cells were left untreated (control, □). Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments.

Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of Daudi, SH-1, Namalwa, and Jurkat cells. Daudi (Burkitt lymphoma), SH-1 (hairy-cell leukemia), Namalwa (Burkitt lymphoma), and Jurkat (T-cell leukemia) cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3 (▨), 25 μM DHA (▦), or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination (▪). For comparison, cells were left untreated (control, □). Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

The aim of our investigation was to evaluate whether DHA is able to enhance As2O3-mediated apoptosis in As2O3-resistant tumor cells. We have found that DHA strongly increases As2O3-mediated apoptosis in the acute myeloid leukemia (AML)–derived cell line HL-60, which has been shown to be resistant to clinically achievable concentrations of 1 to 2 μM As2O3. Treatment of HL-60 cells with the combination of As2O3 and DHA was associated with an increase of intracellular ROS and TBARS concentrations, a reduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential, up-regulation of Bax, and activation of caspase-3 with subsequent apoptotic cell death. Notably, the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA was specific for the leukemic cells, since no apoptotic effect was observed in normal human skin fibroblasts, HMECs, or PBMCs derived from healthy donors. Furthermore, the combined effect with As2O3 was specific for the polyunsaturated fatty acid DHA, since no synergistic effect was observed for the combination of As2O3 with the monounsaturated fatty acid OA.

Recent reports indicate a broad spectrum of antileukemic activity for As2O3 due to its ability to trigger leukemic cell apoptosis via intracellular ROS production.2 In As2O3-sensitive cells such as the APL-derived cell line NB-4, increased intracellular levels of ROS lead to collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome c, activation of the caspase cascade, and, finally, apoptosis.11 However, cells displaying well-established intracellular antioxidant defense mechanisms, such as the AML-derived cell line HL-60, have been shown to be As2O3 resistant.29 To render As2O3-resistant tumor cells such as HL-60 cells more susceptible to As2O3-mediated apoptosis, ways to enhance the effects of As2O3 have been investigated. Importantly, agents modulating the GSH redox system as well as agents increasing intracellular ROS concentrations have been shown to increase As2O3 efficacy in cells otherwise resistant to As2O3.29,30

In recent decades, PUFAs have been extensively studied for their anticancer properties.39 Several investigations have shown that micromolar concentrations of PUFAs such as DHA or eicosapentaenoic acid may exert selective cytotoxicity on malignant tumor cells in vitro.40-48 In addition, it has been shown that exogenously added PUFAs may sensitize tumor cells to ROS-inducing anticancer agents both in vitro and in vivo.31,32 For instance, it could be demonstrated that DHA significantly enhances the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin in the human breast tumor cell line MDA-MB-231 whereas no enhancing effect is observed for mitoxantrone, a drug with low ROS-generating potential.31 The ability of PUFAs to undergo lipid peroxidation seems to play a pivotal role for this enhancement of drug efficacy by PUFAs.31,39,49-51 In response to oxidative stress triggered by ROS-inducing agents, PUFAs undergo free-radical chain reaction breakdown, resulting in the formation of fatty acid hydroxides and hydroperoxides as immediate products and aldehydes among other end products. These, in turn, synergize with ROS induced by the oxidative agent to induce tumor cell apoptosis.31

It is well known that clinically achievable concentrations of As2O3 (that is, 1 to 2 μM) induce insufficient amounts of ROS to induce apoptosis of HL-60 cells in vitro. In the present investigation, we have therefore combined As2O3 with the PUFA DHA (22:6n-3), to elucidate whether the exogenously administered PUFA would enhance the apoptotic effect of As2O3. Indeed, we have found that the combined treatment of cells with As2O3 and DHA strongly increases As2O3-mediated cytotoxicity as evidenced by increased intracellular ROS production, collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, up-regulation of the proapoptotic mitochondrial membrane protein Bax, activation of the caspase cascade, and, finally, apoptosis.

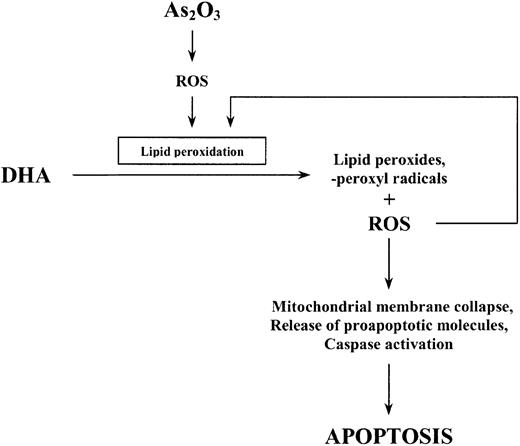

To examine the involvement of lipid peroxidation as a further mechanism by which DHA enhances the effect of As2O3, we also quantified the amount of lipid peroxidation products (TBARS) generated within the cells following combined treatment of HL-60 cells with As2O3 and DHA. Importantly, the increase in As2O3-mediated cell death due to the addition of DHA was concomitant with a significant increase of intracellular TBARS. Conversely, replacement of DHA by monounsaturated, nonperoxidizable OA(18:1n-9) did not result in an increase of intracellular TBARS and was not associated with enhanced cytotoxicity of As2O3. This is in accordance with previous reports showing that PUFAs such as DHA easily undergo lipid peroxidation in response to oxidative stress, resulting in increased cellular cytotoxicity when they are combined with oxidative agents, whereas OA—which has only one double bond—is not a target for free radicals initiating lipid peroxidation and therefore does not lead to enhanced cytotoxicity.37 In our opinion, it is therefore most likely that increased lipid peroxidation along with increased intracellular ROS production mediates the enhancement of As2O3-mediated apoptosis by DHA. We speculate that the initial increase in intracellular ROS observed upon treatment with As2O3 alone subsequently triggers lipid peroxidation of supplemented DHA molecules resulting in increased intracellular TBARS and ROS concentrations, the alteration of mitochondrial membrane metabolism, and, finally, apoptotic cell death (Figure 11).

Schematic representation of the proposed apoptotic pathway induced by As2O3 and DHA in HL-60 cells.

Schematic representation of the proposed apoptotic pathway induced by As2O3 and DHA in HL-60 cells.

To further confirm the involvement of enhanced lipid peroxidation and increased ROS production as potential mechanisms through which DHA modulates As2O3 efficacy, we examined the potency of As2O3 and DHA when the antioxidant vitamin E was added to the cultures.52 Importantly, the addition of vitamin E markedly diminished the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA and caused both intracellular TBARS content and cell viability to return toward baseline level, suggesting an important role for ROS and toxic lipid peroxidation products for the enhancement of As2O3 cytotoxicity by DHA.

Finally, to assess whether the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA can also be observed in other hematologic malignancies, we additionally tested Daudi (Burkitt lymphoma), SH-1 (hairy-cell leukemia), Namalwa (Burkitt lymphoma), and Jurkat (T-cell leukemia) cells. Daudi, SH-1, and Jurkat cells were resistant to either 1 μM As2O3 or 25 μM DHA whereas Namalwa cells were susceptible to treatment with 1 μM As2O3 alone. Importantly, we have found an enhancing effect of DHA on As2O3-mediated cytotoxicity in 2 (Daudi and SH-1) out of the 3 As2O3-resistant cell lines tested, indicating that the combined effect of As2O3 and DHA is not restricted to AML-derived HL-60 cells but may also be observed in other As2O3-resistant hematologic malignancies, including Burkitt lymphoma and hairy-cell leukemia.

However, the lack of a combined effect of As2O3 and DHA in As2O3-resistant Jurkat cells suggests that As2O3 and DHA combination treatment is not equally effective in all malignant cells but that variable sensitivity to the combination may be observed in cells of different origin. This raises important questions with respect to possible determinants of As2O3/DHA sensitivity. Since our data indicate that the combination of As2O3 and DHA exerts its cytotoxic effect through an oxidative mechanism, that is, increased intracellular production of ROS and toxic lipid peroxidation products, the intracellular redox state conceivably plays an important role in the sensitivity of a given cell to As2O3/DHA treatment. Crucial determinants of As2O3/DHA sensitivity might therefore include the intracellular content of GSH and/or antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, glutathione S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, or catalase, which are important scavengers of ROS induced by a variety of agents.11,12,29 Obviously, the knowledge of such determinants of sensitivity would be of particular interest since it would enable screening for malignant hematologic diseases susceptible to As2O3 and DHA combination treatment. Second, the combination of 1 μM As2O3 with 25 μM DHA may constitute a suboptimal dose in certain tumor cells and therefore conceivably explain the lack of a combined effect of As2O3 and DHA in more resistant cells. As a consequence, the determination of an optimal dose of As2O3 and DHA with maximum efficacy and minimal toxicity will be particularly important before further steps toward clinical use of As2O3 and DHA in patients with hematologic malignancies can be taken.

In conclusion, our study illustrates that PUFAs such as DHA might be powerful agents to enhance As2O3-mediated apoptosis in As2O3-resistant leukemia cells. Adding DHA to As2O3 treatment might especially prove useful to treat leukemia patients who are intrinsically resistant to As2O3 as well as to overcome acquired As2O3 resistance in patients with APL. It is noteworthy that the combination of As2O3 and DHA was selectively toxic to the leukemic cells whereas no cytotoxic effect was observed in normal human fibroblasts, HMECs, or PBMCs derived from healthy donors. Thus, it may be possible to use the combination of As2O3 and DHA to selectively induce apoptosis in malignant cells without causing severe side effects in normal tissues. In our opinion, the present data provide for the first time evidence that DHA may help to extend the therapeutic spectrum of As2O3 in leukemia therapy and that, therefore, the combination of As2O3 and DHA could be more broadly applied in the treatment of leukemias other than APL.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 27, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2391.

Supported in part by a research grant from the Jubilee Fund of the National Bank of Austria (project no. 9028) and by research funding from Fresenius Kabi Austria, Graz, Austria.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We wish to thank Heinz Gisslinger and Christine Brostjan for their continuous support.

![Figure 1. Effects of As2O3 and DHA on the viability of HL-60 cells. Cells were treated for 48 hours with 1 μM As2O3,25 μM DHA, or 1 μM As2O3 and 25 μM DHA in combination. For comparison, cells were treated with 25 μM OA ± 1 μM As2O3 or left untreated (control). Cell viability was determined by means of the colorimetric EZ4U viability assay. Values represent the mean (± standard deviation [SD]) of 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/12/10.1182_blood-2002-08-2391/6/m_h81234459001.jpeg?Expires=1769139017&Signature=HJ7QoTlF-83sGfB3UhW2Sv2dSRhX5jRwDcnKQ0SziWZd4Hid5ndFllVLN6VRCJeeqYJ1-xfU~xgh3m~MgsO~-ZmCWx5drZ628ptWvXpA6WE53pzo1dStnVxUlHRI~XovnZDPT6Cd52HPBRzCDsMhlve~Yotne252TLwls9lanYnRGJRG-HwMIdNwWa0HywaM40EwPTaymDUOWjHrEvi7Mwa0W~xShvBTEbEO~2SfztUyVTBHNS3Sz~tx74NklAtMkRVxulvFr0Z9FaowXeYarV0dazYOZP7QOGFtBQuqAN2uSPX80f2Dnq-DiP82BA2nTlG1a0RzYi3r5B5uKgETWg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal