Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) express functional purinergic type 1 receptors, but the effects of adenosine in these antigen-presenting cells have been only marginally investigated. Here, we further characterized the biologic activity of adenosine in immature DCs (iDCs) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–matured DCs (mDCs). Chronic stimulation with adenosine enhanced the macropinocytotic activity and the membrane expression of CD80, CD86, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, and HLA-DR molecules on iDCs. Adenosine also increased LPS-induced CD54, CD80, MHC class I, and HLA-DR molecule expression in mDCs. In addition, adenosine dose-dependently inhibited tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-12 (IL-12) release, whereas it enhanced the secretion of IL-10 from mDCs. The use of selective receptor agonists revealed that the modulation of the cytokine and cell-surface marker profile was due to activation of A2 adenosine receptor. Functionally, adenosine reduced the allostimulatory capacity of iDCs, but not of mDCs. More important, DCs matured in the presence of adenosine had a reduced capacity to induce T helper 1 (Th1) polarization of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes. Finally, adenosine augmented the release of the chemokine CCL17 and inhibited CXCL10 production by mDCs. In aggregate, the results provide initial evidence that adenosine diminishes the capacity of DCs to initiate and amplify Th1 immune responses.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells specialized in the initiation of immune responses by directing the activation and differentiation of naive T lymphocytes.1,2Immature DCs (iDCs) reside in most tissues in order to uptake antigen and alert for danger signals such as microorganisms, inflammatory cytokines, nucleotides, and cell damage.3 Upon exposure to these factors, DCs lose their phagocytotic capacity, migrate to secondary lymphoid organs, and undergo a maturation process that involves acquisition of high levels of membrane major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and costimulatory molecules, such as CD54, CD80, and CD86, as well as CD83. In addition, mature DCs (mDCs) produce a broad panel of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and IL-12.1In secondary lymphoid organs, mDCs present the captured antigens to T cells and direct the development of immune responses.2Depending on the context of maturation, DCs can stimulate the polarized outgrowth of distinct T-cell subsets. DC-derived IL-12 is the most important factor that drives the polarization toward T helper 1 (Th1) cells.1 Beside cytokines, DCs produce chemokines and thus regulate the traffic of T-cell subsets.4 Immature DCs produce thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC, CCL17), but no interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–inducible protein of 10 kDa (IP-10, CXCL10).4 CCL17 is a preferential type 2 lymphocyte chemotaxin, whereas CXCL10 attracts type 1 lymphocytes.5-7Maturation of DCs is accompanied by up-regulation of both chemokines.4

The nucleoside adenosine is an important modulator in the nervous and cardiovascular system.8-12 Although the mechanisms of adenosine release are not well understood, there is evidence of nonlytic secretion of adenosine during hypoxic conditions.13,14 Moreover, significant amounts of adenosine can be generated extracellularly from adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and adenosine monophosphate (AMP) by membrane bound ectoapyrase and 5′ nucleotidase. Because the intracellular content of ATP is in the 5 to 10 mM range, high extracellular concentrations of nucleotides in the 20 to 100 mM or μM range have been detected in injured tissues.13-16 In addition, about 20% of the intracellular ATP content from eukaryotic cells can be released by type III secretion machinery.17Moreover, there is accumulating evidence that activated neutrophils release AMP in the 10 μM range.18 Extracellular ATP, ADP, and AMP are degraded in tissue instantly to adenosine with a half-time of about 200 ms in the brain and lung.19,20Currently, the local concentration of adenosine at inflammatory sites is not known, but measurements in rat heart and brain indicated that under hypoxia the extracellular adenosine concentration is at least in the 10 to 20 μM range.21,22 Besides action on the cardiovascular and nervous system, an anti-inflammatory activity of adenosine A2 receptor during inflammation and tissue damage has been suggested.23 In addition, effects of adenosine on immune cells such as lymphocytes, neutrophils, and DCs have been reported.24-26 Cell responses to adenosine are provoked through interaction with 4 subtypes of G protein–coupled purinergic type 1 receptors named A1, A2a, A2b, and A3 receptors. Because high extracellular concentration of adenosine can be achieved in vivo, the low affinity of adenosine to its receptors in comparison with chemokines or cytokines is a characteristic feature.27 The adenosine A1 and A3 receptors couple to Gi/o/q proteins and mediate inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and activation of phospholipase C.26,28 The A2a/b receptors interact with Gs proteins, which activate adenylyl cyclase generating the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).14,24,25 Recently, we showed that adenosine is a strong chemotaxin and an activator of Gi protein–coupled signal transduction pathways via A1 and A3 receptors in human iDCs, whereas in mDCs it enhances the cAMP level and reduces IL-12 production via A2a receptors.26 Here, we further characterized the biologic activity of adenosine on human DCs.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Adenosine,N6-[2-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(2-methylphenyl)-ethyl]adenosine (DPMA) and 1-deoxy-1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide (IB-MECA) were obtained from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany); and cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) andcis-N-(2-phenylcyclopentyl)azacyclo-tridec-1-en-2-amine hydrochloride (MDL, 12330A), from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Preparation of human DCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated from buffy coats using Ficoll-Paque gradients (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Mononuclear cells were separated with anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (mAb)–coated MicroBeads using MACS single-use separation columns from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Purified CD14+ cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% glutamine, 50 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany), 1000 U/mL IL-4, 200 ng/mL GM-CSF (Natutec, Frankfurt, Germany), and 1% human plasma. After 6 days of culture, monocyte-derived DCs were more than 95% CD1a+, CD80low, CD86low, CD83low, and CD115high. Further differentiation into mature DCs was induced by treatment with 3 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Escherichia coli, serotype 0111:B4; Sigma) for 48 hours. Mature DCs were more than 95% CD80high, CD86high, CD83high, and CD115low. Monoclonal Abs and their respective isotype controls were from Coulter-Immunotech (Krefeld, Germany).29

Cytokine and chemokine assays

IL-10 was measured in DC supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using matched pair of mAbs from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). IL-12 (p70) was analyzed using the OptiEIA kit from BD PharMingen. Quantikine human TNF-α ELISA was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). CXCL10 and CCL17 were measured in DC supernatants by ELISA using matched pair of mAbs and ELISA kit from BD PharMingen and R&D Systems, respectively. Release of IFN-γ and IL-5 from T cells was detected using matched pair of mAbs and OptEIA kit, respectively (BD PharMingen). Samples were assayed in triplicate for each condition.

Flow cytometric analysis

DCs were treated with or without 3 μg/mL LPS in the presence or the absence of nucleoside or adenosine receptor agonists for 48 hours. Cells were then washed and incubated with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated mAbs for 60 minutes at 4°C. Matched isotype mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) was used in control samples. Results are expressed as net mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), which represents the MFI of mAb-labeled cells subtracted from the MFI of control Ig. To detect DC apoptosis and necrosis, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide using the annexin V–FITC apoptosis detection kit from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). Cells were analyzed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

Macropinocytosis assay

Immature or mature DCs were washed, resuspended in complete medium, and pulsed with 1 mg/mL Texas red–conjugated bovine serum albumin (BSA), and then incubated at 37°C or 4°C for one hour. Thereafter, uptake was stopped by adding cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 0.01% NaN3. Cells were then washed 4 times and analyzed by flow cytometry. Surface binding values obtained by incubating cells at 4°C were subtracted from values measured at 37°C. Results are expressed as net MFI.

Mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) assay

CD4+ T lymphocytes were purified from the heavy density fraction (50%-60%) of Percoll gradients (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech AB) followed by immunomagnetic depletion using a mixture of anti–MHC class II, anti-CD19, and anti-CD8 mAb–conjugated beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). Naive T cells were purified (≥ 93% CD4+CD45RA+) by incubation of CD4+T cells with anti-CD45RO mAb followed by a goat anti–mouse Ig coupled to immunomagnetic beads. Immature DCs or mDCs treated or not with adenosine were washed and then cultured in 96-well microculture plates in serial dilutions (78 to 5 × 103 cells/well) together with purified allogeneic CD4+CD45RA+ T lymphocytes (105 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% human serum. Cocultures were pulsed after 5 days with 1 μCi/well (0.037 MBq/well) 3H-thymidine (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for about 16 hours at 37°C, and then harvested onto fiber-coated 96-well plates (Packard Instruments, Groningen, the Netherlands). Radioactivity was measured in a β-counter (Topcount; Packard Instruments).

T-cell differentiation assay

CD4+CD45RA+ T lymphocytes purified as described by MLR assay were cocultured (106cells/well) with allogeneic DCs (5 × 104 cells/well) in a 24-well plate in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% human serum. After 5 days, IFN-γ and IL-5 release was determined by ELISA. For 2-color intracellular staining, T cells were counted and assessed for cell viability by the Trypan blue exclusion test, and then the same number of viable cells for each condition was stimulated with 10 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 1 μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD PharMingen) to prevent cytokine secretion. After 5 hours, T cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD PharMingen) following the manufacturer's protocol, stained with FITC-conjugated mouse anti–IFN-γ and phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated rat anti–IL-4 Abs (BD PharMingen), and finally analyzed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). In control samples, staining was performed using isotype-matched control Abs. T cells that were not restimulated did not show any lymphokine release or staining.

Statistical analysis

The unpaired 2-tailed Student t test was used to compare differences in DC cytokine and chemokine release, T-cell proliferation, and cytokine release. P values of .05 or less were considered significant.

Results

Adenosine influences the expression of costimulatory and MHC molecules

Immature DCs incubated for 48 hours with 10−4 M adenosine showed significantly enhanced expression of membrane CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and MHC class I molecules (Table1), whereas the levels of CD54 and CD83 were unchanged. In addition, adenosine further increased the LPS-induced expression of CD54, CD80, MHC I, and HLA-DR, but under this condition had no influence on CD83 or CD86.

Influence of adenosine on cell-surface expression of membrane molecules on DCs

| DC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | Adenosine . | LPS . | LPS/adenosine . | |

| CD86 | 42.2 ± 5.6 | 67.5 ± 4.7*,† | 388.9 ± 40.8 | 397.4 ± 28.8 |

| CD83 | 25.0 ± 6.4 | 25.2 ± 1.5 | 70.5 ± 6.0 | 77.0 ± 5.8 |

| CD80 | 34.0 ± 8.0 | 62.6 ± 6.7*,† | 161.2 ± 16.4 | 220.5 ± 18.5‡,1-153 |

| CD54 | 786.0 ± 100.1 | 850.2 ± 25.2 | 3055.3 ± 343.5 | 3905.2 ± 65.9‡,1-153 |

| MHC I | 180.2 ± 50.9 | 291.4 ± 19.5†,‡ | 390.1 ± 38.7 | 615.6 ± 57.01-153,1-155 |

| HLA-DR | 174.4 ± 60.8 | 290.6 ± 26.1†,1-155 | 425.4 ± 29.2 | 549.1 ± 26.7‡,1-153 |

| CD1a | 208.3 ± 14.8 | 86.8 ± 23.7†,1-155 | 62.2 ± 19.5 | 30.3 ± 13.2‡,1-153 |

| DC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | Adenosine . | LPS . | LPS/adenosine . | |

| CD86 | 42.2 ± 5.6 | 67.5 ± 4.7*,† | 388.9 ± 40.8 | 397.4 ± 28.8 |

| CD83 | 25.0 ± 6.4 | 25.2 ± 1.5 | 70.5 ± 6.0 | 77.0 ± 5.8 |

| CD80 | 34.0 ± 8.0 | 62.6 ± 6.7*,† | 161.2 ± 16.4 | 220.5 ± 18.5‡,1-153 |

| CD54 | 786.0 ± 100.1 | 850.2 ± 25.2 | 3055.3 ± 343.5 | 3905.2 ± 65.9‡,1-153 |

| MHC I | 180.2 ± 50.9 | 291.4 ± 19.5†,‡ | 390.1 ± 38.7 | 615.6 ± 57.01-153,1-155 |

| HLA-DR | 174.4 ± 60.8 | 290.6 ± 26.1†,1-155 | 425.4 ± 29.2 | 549.1 ± 26.7‡,1-153 |

| CD1a | 208.3 ± 14.8 | 86.8 ± 23.7†,1-155 | 62.2 ± 19.5 | 30.3 ± 13.2‡,1-153 |

DCs were stimulated with and without 10−4 M adenosine in the presence or the absence of 3 μg/mL LPS for 48 hours. The expression of the indicated molecules or isotype controls was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data indicate the net MFI ± SEM (n = 3). Global differences between groups:P ≤ .0001 (ANOVA);

differences between cells stimulated with adenosine or control medium,

LPS/adenosine-stimulated versus LPS-treated cells:

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001; Tukey multiple comparison test.

The effects of adenosine on CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and MHC I membrane levels were dose dependent. Half-maximal and maximal effects on CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and MHC class I molecules were observed with 10−5 and 10−4 M adenosine, respectively (Table 2).

Dose-dependency of adenosine on cell-surface expression of membrane molecules in iDCs

| iDC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | 10−5 M adenosine . | 10−4 M adenosine . | 10−3 M adenosine . | |

| CD86 | 40.1 ± 4.6 | 51.7 ± 4.7 | 71.8 ± 4.6 | 73.6 ± 5.7 |

| CD80 | 32.8 ± 7.1 | 45.3 ± 8.7 | 64.0 ± 7.4 | 67.9 ± 6.2 |

| MHC I | 176.6 ± 48.3 | 223.4 ± 54.7 | 275.5 ± 33.6 | 288.6 ± 33.7 |

| HLA-DR | 171.6 ± 38.8 | 286.9 ± 38.9 | 529.8 ± 39.7 | 569.3 ± 61.5 |

| iDC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | 10−5 M adenosine . | 10−4 M adenosine . | 10−3 M adenosine . | |

| CD86 | 40.1 ± 4.6 | 51.7 ± 4.7 | 71.8 ± 4.6 | 73.6 ± 5.7 |

| CD80 | 32.8 ± 7.1 | 45.3 ± 8.7 | 64.0 ± 7.4 | 67.9 ± 6.2 |

| MHC I | 176.6 ± 48.3 | 223.4 ± 54.7 | 275.5 ± 33.6 | 288.6 ± 33.7 |

| HLA-DR | 171.6 ± 38.8 | 286.9 ± 38.9 | 529.8 ± 39.7 | 569.3 ± 61.5 |

Immature DCs were stimulated with the indicated concentration of adenosine for 48 hours. The expression of the indicated molecules or isotype control was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data indicate the net MFI ± SEM (n = 3).

To characterize the adenosine receptors involved in these DC responses, studies with optimal concentrations of the A1 receptor agonist CHA, the A2 receptor agonist DPMA, and the A3 receptor agonist IB-MECA were performed (Table3). Thereby we could show that the A2 receptor agonist DPMA induced expression of CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, and MHC class I molecules at the cell surface of DCs, whereas the A1 receptor agonist CHA and the A3 receptor agonist IB-MECA had no significant effect.

Influence of selective adenosine receptor agonists on cell surface expression of membrane molecules in iDCs

| iDC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | CHA . | DPMA . | IB-MECA . | |

| CD86 | 40.1 ± 4.62 | 39.8 ± 5.3 | 71.8 ± 4.633-150 | 73.6 ± 5.7 |

| CD80 | 32.8 ± 7.15 | 34.0 ± 6.1 | 59.8 ± 5.733-150 | 37.5 ± 5.2 |

| MHC I | 176.6 ± 48.3 | 171.4 ± 44.1 | 244.7 ± 22.53-151 | 181.1 ± 23.3 |

| HLA-DR | 171.6 ± 38.8 | 191.9 ± 39.1 | 489.9 ± 43.93-152 | 194.7 ± 43.5 |

| iDC . | Treatment . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None . | CHA . | DPMA . | IB-MECA . | |

| CD86 | 40.1 ± 4.62 | 39.8 ± 5.3 | 71.8 ± 4.633-150 | 73.6 ± 5.7 |

| CD80 | 32.8 ± 7.15 | 34.0 ± 6.1 | 59.8 ± 5.733-150 | 37.5 ± 5.2 |

| MHC I | 176.6 ± 48.3 | 171.4 ± 44.1 | 244.7 ± 22.53-151 | 181.1 ± 23.3 |

| HLA-DR | 171.6 ± 38.8 | 191.9 ± 39.1 | 489.9 ± 43.93-152 | 194.7 ± 43.5 |

Immature DCs were stimulated with 10−6 M CHA (A1 receptor agonist), 10−6 M DPMA (A2 receptor agonist), or 10−6 M IB-MECA (A3 receptor agonist) for 48 hours. The expression of the indicated molecules or isotype control was analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers indicate the net MFI ± SEM (n = 3). Differences between cells stimulated with DPMA and with control medium:

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001; Tukey multiple comparison test.

Adenosine enhances macropinocytosis in iDCs and modulates the production of cytokines and chemokines in mDCs

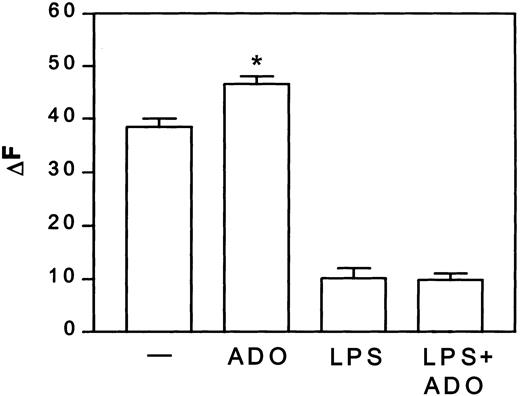

Adenosine enhanced the macropinocytotic activity of iDCs by about 22%, but did not alter the capacity of mDCs to take up albumin (Figure1).

Adenosine increases macropinocytosis in iDCs, but not in mDCs.

DCs were treated with or without 3 μg/mL LPS in the presence or absence of 10−4 M adenosine (ADO) for 24 hours at 37°C. Thereafter, DCs were washed and incubated with 1 mg/mL Texas red–BSA at 37°C. At the indicated time points, cells were stopped with cold PBS, and the Texas red–BSA accumulation was measured by flow cytometry. Fluorescence of cells incubated at 4°C was subtracted from the fluorescence of cells incubated at 37°C and given as ΔF. Data are net MFI ± SEM (n = 4). Differences between iDCs stimulated with and without adenosine, *P < .02.— indicates control.

Adenosine increases macropinocytosis in iDCs, but not in mDCs.

DCs were treated with or without 3 μg/mL LPS in the presence or absence of 10−4 M adenosine (ADO) for 24 hours at 37°C. Thereafter, DCs were washed and incubated with 1 mg/mL Texas red–BSA at 37°C. At the indicated time points, cells were stopped with cold PBS, and the Texas red–BSA accumulation was measured by flow cytometry. Fluorescence of cells incubated at 4°C was subtracted from the fluorescence of cells incubated at 37°C and given as ΔF. Data are net MFI ± SEM (n = 4). Differences between iDCs stimulated with and without adenosine, *P < .02.— indicates control.

Moreover, adenosine had no significant effect on basal cytokine release in iDCs (Figure 2). However, adenosine added together with LPS dose-dependently inhibited the production of IL-12 and TNF-α, whereas it stimulated the release of IL-10. Half-maximal and maximal effects on cytokine secretion were seen in the 10−6 to 10−5 and 10−5 to 10−4 M range, respectively.

Adenosine dose-dependently reduces IL-12 and TNF-α secretion, whereas it augments IL-10 release from mDCs.

DCs were treated with 3 μg/mL LPS in the presence of the indicated concentration of adenosine for 48 hours. Supernatants were harvested and the different cytokines were evaluated by ELISA. The results are expressed as mean pg/mL ± SEM (n = 3). P < .05 between LPS- and LPS + adenosine–treated DCs at concentrations of adenosine more than 10−6 M. Results are representative of 3 different experiments.

Adenosine dose-dependently reduces IL-12 and TNF-α secretion, whereas it augments IL-10 release from mDCs.

DCs were treated with 3 μg/mL LPS in the presence of the indicated concentration of adenosine for 48 hours. Supernatants were harvested and the different cytokines were evaluated by ELISA. The results are expressed as mean pg/mL ± SEM (n = 3). P < .05 between LPS- and LPS + adenosine–treated DCs at concentrations of adenosine more than 10−6 M. Results are representative of 3 different experiments.

The effect of adenosine on mDCs was mimicked by the A2receptor agonist DPMA, whereas optimal doses of the A1receptor agonist CPA and the A3 receptor agonist IB-MECA had no effect (Table 4).

Influence of isotype-selective adenosine receptor agonist on cytokine release by mDCs

| DC . | Control . | CHA . | DPMA* . | IB-MECA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12 | 6327 ± 845 | 6156 ± 932 | 1563 ± 328 | 6547 ± 924 |

| TNF-α | 8552 ± 472 | 8156 ± 672 | 2100 ± 567 | 8295 ± 781 |

| IL-10 | 621 ± 156 | 576 ± 145 | 1872 ± 276 | 645 ± 187 |

| DC . | Control . | CHA . | DPMA* . | IB-MECA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12 | 6327 ± 845 | 6156 ± 932 | 1563 ± 328 | 6547 ± 924 |

| TNF-α | 8552 ± 472 | 8156 ± 672 | 2100 ± 567 | 8295 ± 781 |

| IL-10 | 621 ± 156 | 576 ± 145 | 1872 ± 276 | 645 ± 187 |

DCs were incubated with LPS in the absence or the presence of 10−6 M CHA (A1 receptor agonist), 10−6 M DPMA (A2 receptor agonist), and 10−6 M IB-MECA (A3 receptor agonist) for 48 hours. The release of IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-10 was quantified in the supernatant. Data are given as mean pg/mL/0.2 × 106 cells ± SEM (n = 3). Differences between cells stimulated with DPMA or control medium:P < .01 (*); Tukey multiple comparison test.

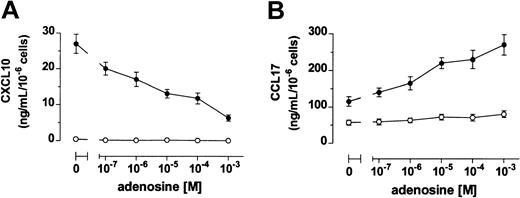

Immature DCs produced high levels of CCL17 and no CXCL10, whereas DCs stimulated with LPS up-regulated the release of both CXCL10 and CCL17 (Figure 3). When DCs where treated with LPS in the presence of adenosine, a dose-dependent reduced secretion of CXCL10 was measured. In contrast, adenosine increased the production of CCL17 in maturing DCs (Figure 3). Again, half-maximal and maximal effects on chemokine release were seen in the 10−6 to 10−5 and 10−5 to 10−4 M range, respectively.

Adenosine inhibits and increases DC release of CXCL10 and CCL17, respectively.

DCs were stimulated (●) or not (○) with 3 μg/mL LPS in the absence or the presence of adenosine. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and CXCL10 (A) and CCL17 (B) were measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ng/mL ± SD of triplicate cultures.P < .02 between LPS- and LPS + adenosine–treated DCs at all the concentrations of adenosine tested. Shown is 1 of 4 experiments performed.

Adenosine inhibits and increases DC release of CXCL10 and CCL17, respectively.

DCs were stimulated (●) or not (○) with 3 μg/mL LPS in the absence or the presence of adenosine. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and CXCL10 (A) and CCL17 (B) were measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ng/mL ± SD of triplicate cultures.P < .02 between LPS- and LPS + adenosine–treated DCs at all the concentrations of adenosine tested. Shown is 1 of 4 experiments performed.

Adenosine influences the T-cell stimulating and polarizing capacity of DCs

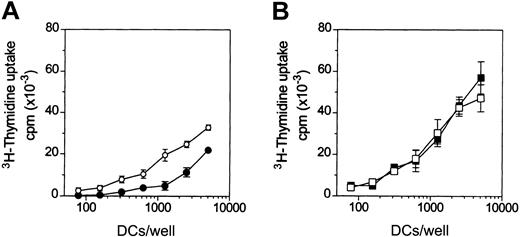

To test the effects of adenosine on the antigen-presenting functions of DCs, the primary MLR assay was used. Adenosine decreased the capacity of iDCs to activate naive (CD45RA+) allogeneic CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A), whereas it had no significant effects on the alloantigen presenting function of mDCs (Figure 4B).

Adenosine reduces the capacity of iDCs to activate allogeneic T cells.

DCs were treated (filled symbols) or not (open symbols) with 10−4 M adenosine in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of 3 μg/mL LPS for 48 hours at 37°C. Thereafter, DCs were washed and cocultured with purified allogeneic CD4+CD45RA+ T cells (105cells/well) in 96-well plates. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured after 5 days. Background T-cell proliferation was less than 1000 counts per minute (cpm). In panel A, differences in T-cell proliferation were significant (P < .02) at more than 312 DCs/well. Results are representative of 4 different experiments. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

Adenosine reduces the capacity of iDCs to activate allogeneic T cells.

DCs were treated (filled symbols) or not (open symbols) with 10−4 M adenosine in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of 3 μg/mL LPS for 48 hours at 37°C. Thereafter, DCs were washed and cocultured with purified allogeneic CD4+CD45RA+ T cells (105cells/well) in 96-well plates. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured after 5 days. Background T-cell proliferation was less than 1000 counts per minute (cpm). In panel A, differences in T-cell proliferation were significant (P < .02) at more than 312 DCs/well. Results are representative of 4 different experiments. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

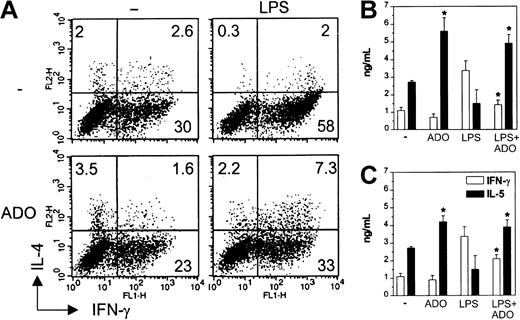

Because IL-12 is the most important factor influencing the differentiation of Th1 cells, we next analyzed the quality of primary T-cell response induced by DCs matured in the presence of adenosine. Naive CD4+CD45RA+ allogeneic T cells primed with iDCs differentiated into Th1, Th2, and Th0 cells, whereas those stimulated with mDCs differentiated mainly into IFN-γ–producing Th1 cells. T cells primed with mDCs exposed to 10−4 M adenosine during maturation displayed an impaired Th1 but enhanced Th0 and Th2 polarization (Figure 5A). These differences could not be attributed to disparities in T-cell viability or number (not shown). In contrast, adenosine had only a minimal effect on T-cell polarization induced by iDCs. The influence on the capacity of DCs to polarize T-cell phenotypes was confirmed measuring the cytokines in the supernatants. Treatment of mDCs with 10−4or 10−5 M adenosine down- and up-regulated IFN-γ and IL-5 release, respectively (Figure 5B-C). T cells stimulated with iDCs showed an unchanged IFN-γ release, but a higher IL-5 secretion.

DCs matured in the presence of adenosine are impaired in their capacity to initiate Th1 responses in vitro.

Immature DCs were left untreated or stimulated with 10−4 M adenosine (A-B) or 10−5 M adenosine (C) or induced to undergo maturation with LPS in the absence or the presence of adenosine for 24 hours. DCs were then used to prime purified allogeneic CD4+CD45RA+ naive T lymphocytes. After 5 days, T cells were restimulated with PMA and ionomycin and then examined for intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 by flow cytometry (A). Only viable cells were gated and analyzed. Numbers indicate the percentage of positive cells in each quadrant. In parallel, supernatants from T cells were evaluated for secreted IFN-γ (■) and IL-5 (▪) (B-C). Results are expressed as mean ng/mL ± SD of triplicate cultures. *P < .02 between cytokines secreted by T cells stimulated with DCs treated or not with adenosine. Experiments were repeated 3 times from different donors with similar results. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

DCs matured in the presence of adenosine are impaired in their capacity to initiate Th1 responses in vitro.

Immature DCs were left untreated or stimulated with 10−4 M adenosine (A-B) or 10−5 M adenosine (C) or induced to undergo maturation with LPS in the absence or the presence of adenosine for 24 hours. DCs were then used to prime purified allogeneic CD4+CD45RA+ naive T lymphocytes. After 5 days, T cells were restimulated with PMA and ionomycin and then examined for intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 by flow cytometry (A). Only viable cells were gated and analyzed. Numbers indicate the percentage of positive cells in each quadrant. In parallel, supernatants from T cells were evaluated for secreted IFN-γ (■) and IL-5 (▪) (B-C). Results are expressed as mean ng/mL ± SD of triplicate cultures. *P < .02 between cytokines secreted by T cells stimulated with DCs treated or not with adenosine. Experiments were repeated 3 times from different donors with similar results. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

Discussion

Recent findings suggest that nucleotides, well-known extracellular mediators in the cardiovascular and nervous systems, play a central role in inflammation and immunomodulation. Because of the elevated intracellular content of ATP, high extracellular concentrations of nucleotides in the 100 mM to μM range have been detected in tissues during organ injury and traumatic shock.13-16Extracellular ATP binds to purinergic type 2 receptors, which are expressed on monocytes/macrophages, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and DCs.30-33 These receptors are coupled to an array of different responses, such as chemotaxis, generation of nitric oxide or superoxide anions, secretion of lysosomal constituents, release of cytokines, and cytotoxicity.30-34 ATP induces a distorted maturation of DCs and inhibits their capacity to initiate a Th1 response.35 Furthermore, DCs exposed to extracellular ATP acquire the migratory properties of mature cells and show a reduced capacity to attract type 1 lymphocytes.4 In the extracellular space, ATP is very rapidly subjected to hydrolysis by ubiquitous ecto-ATPases and ectonucleotidases resulting in final degradation to adenosine.13,14 The half-time degradation of nucleotides to adenosine in the extracellular space is thought to occur in the brain and lung in the 200 ms range.19,20 Moreover, during hypoxic conditions accumulation of adenosine in the extracellular space might also occur by a poorly understood nonlytic secretion mechanism.13,14Therefore, measurements in rat heart and brain indicated that under hypoxia the extracellular adenosine concentration is to be expected in the 10 to 20 μM range.21,22 Cellular response to adenosine is evoked through activation of 4 different G protein–coupled purinergic type 1 receptors, the Giprotein–coupled A1 and A3 receptors as well as Gs protein–coupled A2a and A2b receptors.26,28 Recently, we could link A1 and A3 receptors to chemotaxis response in iDCs, whereas A2a receptor regulates IL-12 production in mDCs.26 Despite increasing observations about the effects of nucleotides on leukocytes, no thorough characterization of adenosine action on DCs has been carried out.

Here we showed that adenosine up-regulated the membrane expression of CD80, CD86, MHC class I, and HLA-DR molecules on iDCs and enhanced CD54, CD80, MHC class I, and HLA-DR expression on mDCs. The use of selective receptor agonists revealed that the modulation of the cell-surface marker profile was due to activation of the A2receptor. This receptor interacts with Gs proteins, which activate adenylyl cyclase and stimulate formation of the second messenger cAMP in mDCs.26 Cholera toxin, which continuously activates adenylyl cyclase via ADP-ribosylation of Gs proteins, has also been reported to promote partial DC maturation with up-regulation of CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR.36,37 Therefore, our data are consistent with the concept that cAMP regulates crucial steps in the process of DC maturation.26,27 However, we observed that adenosine had no influence on the expression of CD83 or on the basal release of IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-10, and it even enhanced the macropinocytotic activity of iDCs. Therefore, adenosine by itself has only a very limited capacity to induce DC maturation. More interestingly, adenosine inhibited TNF-α and IL-12 production and enhanced secretion of IL-10 in mDCs, also through activation of the A2a receptor. Half-maximal and maximal effects of adenosine on cytokine release were seen in the 10−6 to 10−5 and 10−5 to 10−4 M range, respectively. Because under hypoxia extracellular adenosine concentrations are to be expected in the 10 to 20 μM range,21,22 the physiologic relevance of our findings can be postulated. Moreover, this effect is well in accordance with other studies using cholera toxin and Gsprotein–stimulating ligands such as histamine linking adenylyl cyclase activation with the switch of high IL-12 and TNF-α/low IL-10 production toward a low IL-12 and TNF-α/high IL-10 release during DC maturation.36-38

Beside cytokines, DCs produce chemokines and regulate the traffic of T-cell subsets.4 Adenosine also affected the pattern of chemokines released by mDCs, but not iDCs. Adenosine supported an augmented release of CCL17, whereas it inhibited the production of CXCL10 by mDCs. Half-maximal and maximal effects of adenosine on chemokines were comparable with the situation on cytokines. Prostaglandin E2 and other cAMP-elevating agents were reported to have similar modulatory effects on chemokine production by mDCs.36,39 CCL17 and CXCL10 attract preferentially type 2 and type 1 lymphocytes, respectively.4-6 In addition, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express the corresponding chemokine receptors CCR4 and CXCR3 at different levels, and thus CCL17 and CXCR3 are active predominantly on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.40 Therefore, one could assume that DCs exposed to adenosine during maturation attract preferentially CD4+ and type 2 and not CD8+ and type 1 lymphocytes, resulting in a diminished capacity to amplify type 1 immune responses and favoring the outcome of type 2 immune responses.

Functional assays indicated that adenosine did not influence the antigen-presenting capacities of mDCs toward allogeneic naive T cells and reduced the low T-cell–activating capability of iDCs, although it increased the membrane expression of molecules implicated in T-cell activation. Whether this effect of adenosine on iDCs is mediated by unidentified soluble factors or an altered expression of other costimulatory molecules is currently only a matter of speculation. More important, consistent with the capacity of adenosine to inhibit IL-12 release, DCs maturated in the presence of adenosine induced a higher percentage of Th0/Th2 cells compared with the predominant Th1 differentiation promoted by LPS-mDCs. This latter finding might indicate that extracellular adenosine at inflammatory and hypoxic sites limits the amplification of Th1 immune responses. This finding would be well in agreement with a recent report suggesting an anti-inflammatory capacity of adenosine A2 receptor during inflammation and tissue damage.23

In conclusion, our study implicates that adenosine has a broad range of effects on DCs, including regulation of antigen capture, expression of membrane molecules, and cytokine as well as chemokine release; and ultimately adenosine may diminish the capacity of DCs to initiate and amplify Th1 immune responses.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 21, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2113.

E.P. and S.C. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Johannes Norgauer, Department of Experimental Dermatology, Hauptstraße 7, D-79104 Freiburg i Br, Germany; e-mail:norgauer@haut.ukl.uni-freiburg.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal