Dying cells, apoptotic or necrotic, are swiftly eliminated by professional phagocytes. We previously reported that CD47 engagement by CD47 mAb or thrombospondin induced caspase-independent cell death of chronic lymphocytic leukemic B cells (B-CLL). Here we show that human immature dendritic cells (iDCs) phagocytosed the CD47 mAb–killed leukemic cells in the absence of caspases 3, 7, 8, and 9 activation in the malignant lymphocytes. Yet the dead cells displayed the cytoplasmic features of apoptosis, including cell shrinkage, phosphatidylserine exposure, and decreased mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm). CD47 mAb–induced cell death also occurred in normal resting and activated lymphocytes, with B-CLL cells demonstrating the highest susceptibility. Importantly, iDCs and CD34+ progenitors were resistant. Structure-function studies in cell lines transfected with various CD47 chimeras demonstrated that killing exclusively required the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the CD47 molecule. Cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, and antimycin A, an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transfer, completely suppressed CD47-induced phosphatidylserine exposure. Interestingly, CD47 ligation failed to induce cell death in mononuclear cells isolated from Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) patients, suggesting the involvement of Cdc42/WAS protein (WASP) signaling pathway. We propose that CD47-induced caspase-independent cell death be mediated by cytoskeleton reorganization. This form of cell death may be relevant to maintenance of homeostasis and as such might be explored for the development of future therapeutic approaches in lymphoid malignancies.

Introduction

Apoptosis is a noninflammatory destruction process essential to the regulation of immune system and homeostasis.1,2 It provides molecular basis for T- and B-cell development,3 induction of immune tolerance, and termination of normal immune response.4 By contrast, necrosis is perceived by the immune system as a danger signal that triggers inflammatory response and acquired immunity. Classically, the activation and function of a set of proteinases, the caspases, is the key event in apoptosis, with mitochondria playing a central role.5,6 A critical event, besides the execution phase of apoptosis, is the engulfment of dying cells by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) before the dead cells disgorge their toxic materials in the surrounding milieu.7

In recent years, cell death other than necrosis was reported to occur in the absence of caspase activation in hematopoietic cells; it included glucocorticoid-induced death of thymocytes, Bax-mediated cell death, and death of cell lines induced by growth factor withdrawal.8-10 A growing number of surface molecules were shown to be involved in the induction of this nonclassical caspase-independent cell death. Engagement of CD2, CD45, CD47, CD99, and MHC (major histocompatibility complex) class II and I activated this death process.11-17Caspase-independent cell death induced by CD47 ligation in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemic (B-CLL) cells was characterized by cell shrinkage, exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS), and mitochondrial matrix swelling in complete absence of nuclear degradation.13

CD47 antigen is ubiquitously expressed on hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells.18 It serves as a receptor for thrombospondin (TSP) and as a ligand for transmembrane signal regulatory protein (SIRP-α), mainly expressed on myeloid and neuronal cells.19,20 Through its association with integrins of β1, β2, and β3 families, it initiated heterotrimeric G-protein signaling and thus modulated cell motility, leukocyte adhesion and migration, phagocytosis, and platelet activation.21 On immune cells, CD47 ligation by soluble mAbs was shown to inhibit cytokine production by APCs and interleukin-12 (IL-12) responsiveness by neonatal and adult T cells.22-25 When immobilized, CD47 mAb costimulated T-cell receptor (TCR)–activated T cells.26,27 Thus, the biologic consequences of CD47 activation seemingly vary according to (1) the way the molecule is engaged, (2) the surface molecules it interacts with, and (3) its conformation and membrane localization, all of which depend on the cell type on which CD47 is expressed.26 28-32

The molecular basis for caspase-independent cell death remains elusive. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), released by mitochondria, induced caspase-independent nuclear degradation.33 In most of the studies, sole PS externalization in the presence of the broad caspase inhibitor Z-VAD.fmk (benzyloxycarbonyl–Val-Ala-Asp–OMe–fluoromethyl ketone) was used to define caspase-independent cell death pathway. Coexistence of caspase-dependent and -independent pathways occurred in various systems, including CD2 and CD95 ligation.11,34,35 For instance, in CD2-mediated apoptosis of T lymphocytes, the mitochondrial release of AIF preceded the dissipation of transmembrane potential (ΔΨm), the release of cytochrome c (cyt c), and the caspase-dependent execution phase of apoptosis.36

Our present findings confirm and extend to other cell populations our previous observations that CD47 ligation exclusively induced the cytoplasmic events of apoptosis in B-CLL cells. We here show that DCs recognized and eliminated B-CLL dead cells and present evidence that cytoskeleton rearrangement was a triggering event in ΔΨm loss and PS exposure after CD47 ligation on human cells.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Diagnosis of B-CLL patients included in this study was based on clinical examination and peripheral blood count. CLL was defined as > 5000/μL lymphocytes expressing CD5, CD20, and CD23. Authorized consent forms for patients were obtained before blood collection. Patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) exhibited typical features, that is, thrombocytopenia with small platelets, eczema, and susceptibility to infections, a severe clinical phenotype. In patient 1, A nucleotide insertion at position 147 in exon 2 of the WAS gene was detected. In patients 2 and 3 there was a C to T missense mutation at nucleotide 631 in exon 7 and 155 in exon 1, respectively. In patient 4, a G to A mutation at position 777 in intron 8 was found. Blood samples were obtained following informed consent of parents according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Centre de Recherche du CHUM and Hôpital Necker.

Cell lines and transfectants

RAJI is a Burkitt lymphoma; RPMI 8226 and RPMI 8866 are B-lymphocytic cell lines; Jurkat is a T-cell hybridoma; KU812 is a granulocytic cell line; U937 and THP-1 are monocytic cell lines; K-562 is a chronic myelogenic leukemia cell; OV10 is an ovarian carcinoma transfected with CD47 cDNA37; and JinB8 is a CD47-negative Jurkat cell line.26 The different cDNAs and constructs used in this study were previously described.26Transfected Jurkat, JinB8, and U937 cells were sorted for high transgene expression using a FACSort (Lysys II Software, Becton Dickinson, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Reagents

Recombinant human IL-4, soluble CD40 ligand, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were kindly provided by Immunex (Seattle, WA) and Dr D. Bron (Institut Bordet, Brussels, Belgium), respectively. Dr R.-P. Sekaly (Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada) kindly provided polyclonal anti–caspase-3 Ab. Anti–human CD3 (UCHT-1) was provided by P. Beverley (University College and Middlesex School of Medicine, London, United Kingdom). Isotype-matched negative control mAb (mouse IgG1) was prepared in our laboratory.

The other antibodies and reagents used in this study were purchased from manufacturers as indicated: anti-CD47 mAbs (clone B6H12), Bioscience (Camarillo, CA); polyclonal anti–caspase-8, Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); polyclonal antibody against caspase-9 and anti–mouse CD8-α (clone 53-6.7), Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); and anti–caspase-7 mAb, Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY).

Cell preparation and culture conditions

B cells were isolated from CLL patients or from tonsils by density gradient centrifugation of heparinized blood or cell suspension, respectively, using Lymphoprep (Nycomed, Olso, Norway) followed by one cycle of rosetting with S-(2 aminoethyl) isothiouronium bromide–treated (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) sheep red blood cells to deplete T cells. B-cell purity was shown to be > 98% by flow cytometry (FACSort, Becton Dickinson). Highly purified T cells were obtained from monocyte-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers by rosetting with aminoethylisothiouronium bromide (AET)–treated sheep red blood cells (SRBC), followed by treatment of rosette-forming cells with Lympho-Kwik T (One Lambda, Los Angeles, CA), following manufacturer's recommendations. Cell purity was assessed by flow cytometry using phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-CD3, anti-CD4, or anti-CD8 mAbs (Ancell, London, ON, Canada) and was shown to be > 98%. CD34+ cells were obtained from heparinized cord blood using the Dynal CD34 progenitor cell selection system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dynal Skøyen, Oslo, Norway). Human monocyte-derived iDCs were prepared exactly as described.28

Highly purified lymphocytes were cultured at 4 × 106/mL, iDC, lines, and transfectants at 2 × 106/mL in 100 μL of HB101 serum-free synthetic medium (Irvine Scientific, Edmonton, AB, Canada) or in special medium when indicated, on flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Nunc, Edmonton, AB, Canada) in the presence of soluble or immobilized mAbs. Plates were precoated with anti-CD47 or anti–CD8-α mAbs at 10 μg/mL in 100 μL 0.1M NaHCO3, pH 9, overnight at 4°C, then washed and blocked with medium. The following inhibitors were added 15 minutes before plating cells when indicated; only cytochalasin D–treated cells were washed before plating: antimycin A (30 μM) (Sigma, St Louis, MO), pertussis toxin (25-100 ng/mL), cytochalasin D (20 μM), rottlerin (5-20 μM) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), cyclosporin A (5 μM), aristolochic acid (50 μM), and bongkrekic acid (50 μM) (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA).

For potassium efflux experiments, cells were cultured in 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) Na+K+-free RPMI medium, supplemented with normal or inverted [Na+]/[K+] ratio as described.38

Phagocytosis assay

Freshly purified B-CLL cells were stained with PKH26 red fluorescent cell linker (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions before induction of apoptosis by culture for 16 hours on immobilized CD47 mAb, hydrocortisone (HC) (5 × 10−4 M), or soluble CD47 mAb as negative control. Cells were washed and given to iDCs (2 × 105/mL) as a phagocytic meal (10 apoptotic cells per iDC) for 3 hours at 37°C. Endocytosis of PKH26-stained B cells was determined by fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanner (FACS) after gating on live iDCs.

Flow cytometry analysis

CD47 and constructs expression was assessed using a 2-step procedure. Briefly, cells were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with biotinylated CD47 mAb (B6H12) or unconjugated anti-CD8α (clone no. 53-6.7) or isotype-matched control mAb (5 μg/mL). After washing, cells were incubated with PE-labeled streptavidin or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antirat mAb (Ancell) and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSort, Becton Dickinson).

Assays for apoptosis

Detection of PS exposure, caspase 3 activity, and decrease in ΔΨm were performed by flow cytometry using a FACSort (Lysys II Software, Becton Dickinson). For detection of PS exposure, cells were double-stained with FITC-labeled annexin-V (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and propidium iodide (PI) at 2 μg/mL (Sigma). Decrease of ΔΨm was assessed using 3,3′–dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) (Molecular Probes, Hornby, ON, Canada). Caspase 3 activity was detected by flow cytometry in unfixed cells using a fluorogenic substrate (PhiPhilux, OncoImmunium, Gaithersburg, MD). Caspases 3, 7, and 9 cleavage products and caspase 8 expression were analyzed by Western blotting. Briefly, 5 × 106 cells were directly lysed in hot sample buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were then boiled for 5 minutes, electrophorezed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred onto polyvinylidenefluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Mississauga, MN). Membranes were probed with indicated antibodies, and immunoreactive products were revealed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Baie d'Urfe, QC, Canada).

CD47-induced cell death was calculated as follows:

Statistical analysis

The Student paired t test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Engulfment by professional phagocytes of CD47 mAb-treated B-CLL cells dying in the absence of caspase activation

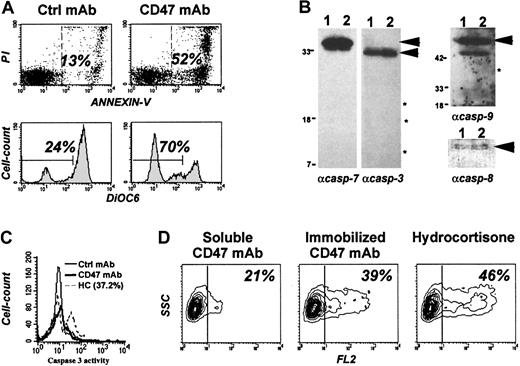

We previously reported that CD47 ligation by immobilized anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies (CD47 mAbs) or its natural ligand, TSP,13 induced caspase-independent cell death in B-CLL cells. This cell death was characterized by the cytoplasmic features of apoptosis. They included cell shrinking, exposure of PS to the outer leaflet membrane and, as shown in Figure1A, a drop in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) as demonstrated by decreased 3,3′–dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) staining. This cell death was considered to be caspase independent since the nucleus of the leukemic dead cells remained intact and PS exposure was not prevented by the presence of the broad caspase inhibitor z-Val-Ala-Asp-(OMe)–fluoromethylketone (zVAD-fmk).13 To formally demonstrate that the caspase remained inactive during this process, we performed Western blot analysis (Figure 1B) to search for the cleavage products of caspases in CD47 mAb-treated leukemic cells. We failed to detect any cleavage products of caspases 3, 7, and 9, and similar amounts of procaspase-8 were found in immobilized CD47 mAb and control mAb-treated B-CLL cells. The absence of caspases 3/7 activity in individual CD47-treated cells was confirmed by flow cytometry using a fluorogenic caspase substrate (Figure 1C). HC-treated B-CLL cells displayed caspase 3 activity. Note that B-CLL cells with a low level of spontaneous apoptosis were selected for these experiments.

Immature dendritic cells efficiently phagocytosed B-CLL cells killed by CD47-induced caspase-independent pathway.

Freshly isolated B-CLL cells were cultured in the presence of soluble or immobilized CD47 mAb (10 μg/mL), control mAb (10 μg/mL), or HC (5 × 10−4 M). (A) Cells were double-stained with FITC-labeled annexin-V and PI (upper graphs) or with DiOC6(lower graphs) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC). (B) Soluble (lane 1) or immobilized (lane 2) CD47 mAb-treated cells were lysed, and Western blot analysis was performed for detection of caspases 3, 7, 8, and 9 cleavage products (as indicated by *). Asterisks indicate “expected molecular weight” of caspase cleavage products; arrowheads, molecular weight of procaspases. (C) Caspase 3 activity was measured after 48 hours by flow cytometry using the cell permeable fluorogenic substrate DEVDase. (D) B-CLL cells were stained in red with PKH26 linker before treatment overnight with soluble or immobilized CD47 mAb or HC. Cells were then cocultured for 3 hours with iDCs at a 10:1 ratio. The mixture was analyzed by flow cytometry for red fluorescence (FL2) after gating on iDCs. Shown are percent of iDCs that have phagocytosed red dead cells. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

Immature dendritic cells efficiently phagocytosed B-CLL cells killed by CD47-induced caspase-independent pathway.

Freshly isolated B-CLL cells were cultured in the presence of soluble or immobilized CD47 mAb (10 μg/mL), control mAb (10 μg/mL), or HC (5 × 10−4 M). (A) Cells were double-stained with FITC-labeled annexin-V and PI (upper graphs) or with DiOC6(lower graphs) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC). (B) Soluble (lane 1) or immobilized (lane 2) CD47 mAb-treated cells were lysed, and Western blot analysis was performed for detection of caspases 3, 7, 8, and 9 cleavage products (as indicated by *). Asterisks indicate “expected molecular weight” of caspase cleavage products; arrowheads, molecular weight of procaspases. (C) Caspase 3 activity was measured after 48 hours by flow cytometry using the cell permeable fluorogenic substrate DEVDase. (D) B-CLL cells were stained in red with PKH26 linker before treatment overnight with soluble or immobilized CD47 mAb or HC. Cells were then cocultured for 3 hours with iDCs at a 10:1 ratio. The mixture was analyzed by flow cytometry for red fluorescence (FL2) after gating on iDCs. Shown are percent of iDCs that have phagocytosed red dead cells. One representative experiment of 3 is shown.

Both caspase activation and PS exposure generally have been considered as prerequisites for recognition and phagocytosis of cells dying by apoptosis.39,40 It was therefore important to determine whether CD47 mAb–killed B-CLL cells could signal their death to phagocytes and be eliminated. To test this hypothesis, we performed a phagocytosis assay using human monocyte-derived iDCs as professional phagocytes.41 B-CLL cells were stained by PKH26, a nontoxic red fluorescent cell-linker, and exposed for 16 hours to immobilized CD47 mAb or HC, a drug that induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in the leukemic cells.42 Soluble CD47 mAb did not induce cell death13 nor Fc-mediated phagocytosis23 and was used as negative control. Treated samples were cocultured with iDCs for 3 hours. Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry by quantifying FL2 fluorescence after gating on iDCs (by size scatter). Results indicated that B-CLL killed by immobilized CD47 mAb were phagocytosed as efficiently as HC-treated cells (39% vs 46% FL2-positive cells) (Figure 1D). Note that each cell preparation was stained separately with FITC-labeled annexin-V to evaluate their percentage of annexin-V–positive cells (39%, 75%, and 83% for soluble, immobilized CD47 mAb, and HC, respectively).

Taken together, these results indicate that the caspase-independent death signal delivered by CD47 ligation to B-CLL cells is sufficient to allow their elimination by iDCs.

Blood cell susceptibility to CD47-induced cell death

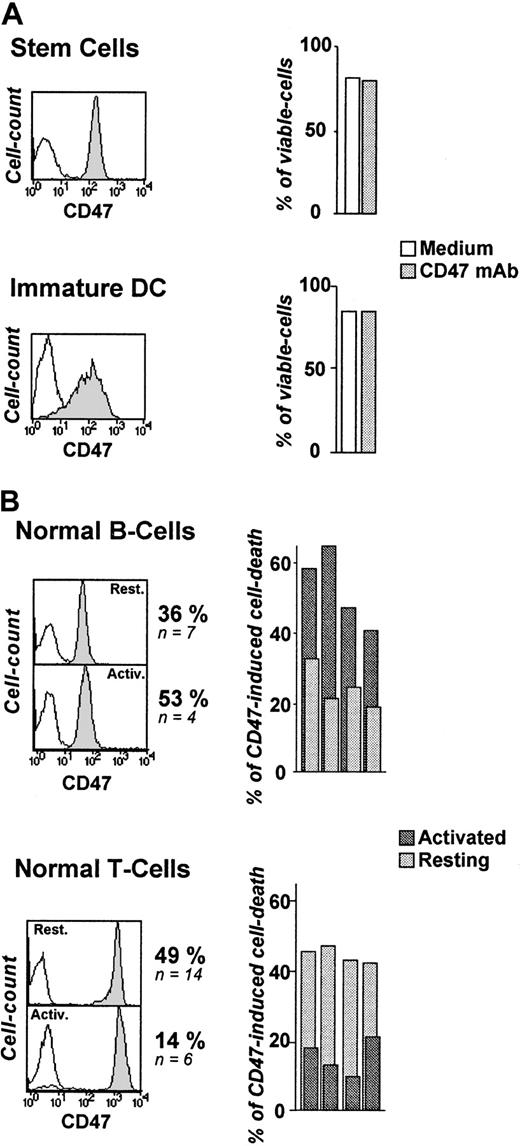

Since CD47 Ag is ubiquitously expressed on hematopoietic cells, we assessed the in vitro sensitivity of normal blood cells to CD47-induced cell death. From the perspective of a potential therapeutic use of this mAb, we first examined CD34+ cells since they represent the pool of hematopoietic progenitors.43 44 As depicted in Figure 2A, CD34+ cells remained totally insensitive to CD47 mAb–induced killing (0% of cell-death induction, n = 6), despite their high level of CD47 expression. Immature DCs are major players in the clearance of apoptotic cells. Like CD34+ cells, they were resistant to CD47-induced cell death (0%, n = 4) (Figure 2A).

Differential susceptibility of normal human blood cells to CD47-induced cell death.

(A-B) Cord-blood CD34+ cells (stem cells) (n = 6), monocyte-derived iDCs (n = 4), resting and activated tonsillar B cells (n = 4), and peripheral T cells (n = 4) were stained for CD47 expression (B6H12 mAb) and analyzed by flow cytometry: isotype-control mAb (open histogram), CD47 mAb (shaded histogram). (A) Stem cells and iDCs were cultured in the absence or presence of immobilized CD47 mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 18 hours and double-stained with FITC-labeled annexin-V and PI. Shown are percent of viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−). (B) Resting T and B cells were left unstimulated or activated for 48 hours with plastic-coated anti-CD3 (3 μg/mL) or sCD40L (1 μg/mL) + IL-4 (10 ng/mL), respectively, and then cultured overnight in the absence or presence of immobilized CD47 mAbs. The mean percent of CD47-induced cell death, calculated as indicated in “Patients, materials, and methods” are shown.

Differential susceptibility of normal human blood cells to CD47-induced cell death.

(A-B) Cord-blood CD34+ cells (stem cells) (n = 6), monocyte-derived iDCs (n = 4), resting and activated tonsillar B cells (n = 4), and peripheral T cells (n = 4) were stained for CD47 expression (B6H12 mAb) and analyzed by flow cytometry: isotype-control mAb (open histogram), CD47 mAb (shaded histogram). (A) Stem cells and iDCs were cultured in the absence or presence of immobilized CD47 mAbs (10 μg/mL) for 18 hours and double-stained with FITC-labeled annexin-V and PI. Shown are percent of viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−). (B) Resting T and B cells were left unstimulated or activated for 48 hours with plastic-coated anti-CD3 (3 μg/mL) or sCD40L (1 μg/mL) + IL-4 (10 ng/mL), respectively, and then cultured overnight in the absence or presence of immobilized CD47 mAbs. The mean percent of CD47-induced cell death, calculated as indicated in “Patients, materials, and methods” are shown.

We next observed a differential induction of cell death in normal resting and activated B and T lymphocytes. The percentage of CD47-induced cell death in normal resting B and T cells was 36% (n = 7, P < .01) and 49% (n = 14,P < .01), respectively (Figure 2B). B-CLL cells displayed the highest susceptibility (64%, n = 10). Unexpectedly, anti–CD3-stimulated T lymphocytes became almost insensitive to CD47 mAb-killing, whereas T-cell–dependent B-cell activation (sCD40L + IL-4) significantly increased the level of death induction (P < .01). Activation did not modulate CD47 expression as detected by CD47 mAb (clone B6H12) (Figure 2B).

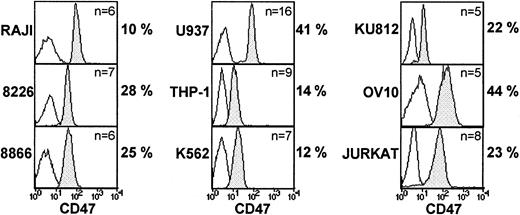

Human cell lines represent the malignant counterpart of lymphoid and myeloid cells at different stages of maturation. In this context, we examined 4 lymphoid cell lines (RAJI, RPMI-8226, 8866, and Jurkat), 3 myeloid cell lines (U937, THP-1, and K-562), one granulocytic cell line (KU812), as well as the ovarian carcinoma cell line, OV10,37 transfected with CD47 cDNA. As shown in Figure3, these cell lines displayed differential sensitivity to CD47 mAb, with no correlation, as in untransformed cells, with the level of CD47 expression. In addition, the level of CD47-induced cell death induction did not discriminate between specific cell lineage, RAJI, THP-1, and K562 being resistant. Of interest, OV10 CD47 transfectants were efficiently killed by CD47 mAb (44% of death induction, n = 5, P < .001), indicating that CD47 expression was sufficient to confer cell death susceptibility in a cell that did not primarily express the CD47 molecule.

Susceptibility of human cell lines to CD47-induced cell death: lack of correlation between CD47 expression and CD47-induced cell death.

Various cell lines were stained for CD47 expression using B6H12 mAb: isotype-control mAb (open histogram) and CD47 mAb (shaded histogram). Cells were cultured overnight on immobilized control or CD47 mAb analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are the mean percents of CD47-induced cell death, calculated as indicated in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

Susceptibility of human cell lines to CD47-induced cell death: lack of correlation between CD47 expression and CD47-induced cell death.

Various cell lines were stained for CD47 expression using B6H12 mAb: isotype-control mAb (open histogram) and CD47 mAb (shaded histogram). Cells were cultured overnight on immobilized control or CD47 mAb analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are the mean percents of CD47-induced cell death, calculated as indicated in “Patients, materials, and methods.”

From this data, we conclude that normal as well as transformed cells display differential susceptibility to CD47-induced cell death. CD34+ cells and immature DCs are resistant, whereas cell activation differentially modulates the intensity of the response, regardless of the level of CD47 expression.

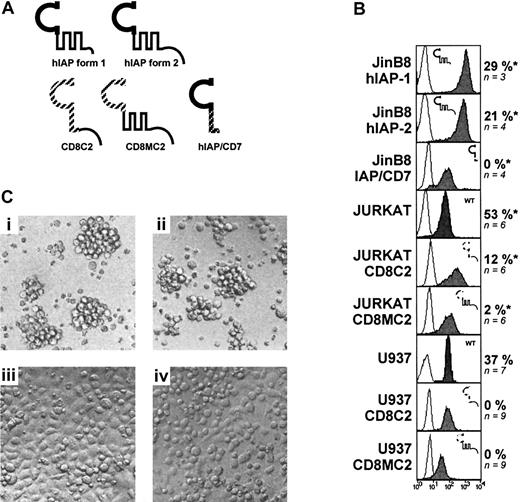

CD47 extracellular and multiply membrane-spanning domains are necessary to signal cell death

As indicated above, Jurkat and U937 cell lines were sensitive to CD47-induced cell death. These cell lines were therefore suitable to perform structure-function studies to determine which portion(s) of the CD47 molecule was dispensable to mediate the cell death signaling. CD47 molecule is made of an extracellular immunoglobulinlike domain (IgV), a 5-membrane spanning domain (multiply membrane spanning [MMS]), and a cytoplasmic tail displaying 4 alternatively spliced isoforms (form 1 to 4 in order of increasing length).18 45 Form 2 of CD47 is predominant in the hematopoietic lineage, while the nearly tailless form 1 (only 3 amino acids) is expressed in keratinocytes and endothelial cells.

We first examined whether the cytoplasmic tail of CD47 was required. We used JinB8 cells, a CD47-negative Jurkat cell line,46 transfected with either of the 2 native splice forms (hIAP-form 1 and 2) or a chimera, CD8C2, made of the extracellular membrane domain of mouse CD8α fused to the cytoplasmic tail of CD47 form 2. Some experiments were performed on a U937 cell line transfected with CD8C2 cDNA. Since we observed that Jurkat sensitivity to CD47-induced cell death was augmented by pretreatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 hours, we used PMA-activated cells in the next experiments. Results shown in Figure 4B indicate that the cytoplasmic tail of CD47 is not required to signal cell death. First, engagement of hIAP-form 1 and 2 molecules, equally expressed on JinB8, by immobilized CD47 mAb induced similar level of cell death (29% vs 21% death induction). Secondly, ligation of the chimera CD8C2 by CD8 mAb did not mediate cell death, either in JinB8, U937 or Jurkat (Figure 4B and data not shown). Of interest, PMA-activated Jurkat-CD8C2 cells did spread when endogenous CD47 or CD8C2 chimera was engaged by immobilized CD47 or anti-CD8 mAb, respectively (Figure 4C), indicating that the failure to induce cell death was not due to inappropriate chimera ligation.

Requirement for both extracellular and transmembrane domains for CD47-induced cell death.

(A) Various constructs or/and chimeras of the CD47 molecule (described in “Patients, materials, and methods”) were transfected into U937, Jurkat, or JinB8 (CD47−/−) cell lines. (B) Expression of the CD47 products (gray histograms) was determined by staining with B6H12 mAb (for hIAP form 1 and 2, IAP/CD7) or antimouse CD8α mAb (for CD8-MC2 and CD8-C2). Expression of endogenous CD47 (Jurkat and U937): cells were cultured overnight on immobilized antimouse CD8-α or CD47 mAb (10 μg/mL). *Jurkat and JinB8 transfectants were pretreated with PMA for 24 hours (2 ng/mL) before killing. CD47-induced cell death was calculated as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” (C) Light microscopy of PMA-activated Jurkat cells transfected with CD8-C2 construct. Untreated cells (i), cells cultured for 18 hours with soluble (ii), immobilized CD47 mAb (iii) or immobilized antimouse CD8α mAb (iv).

Requirement for both extracellular and transmembrane domains for CD47-induced cell death.

(A) Various constructs or/and chimeras of the CD47 molecule (described in “Patients, materials, and methods”) were transfected into U937, Jurkat, or JinB8 (CD47−/−) cell lines. (B) Expression of the CD47 products (gray histograms) was determined by staining with B6H12 mAb (for hIAP form 1 and 2, IAP/CD7) or antimouse CD8α mAb (for CD8-MC2 and CD8-C2). Expression of endogenous CD47 (Jurkat and U937): cells were cultured overnight on immobilized antimouse CD8-α or CD47 mAb (10 μg/mL). *Jurkat and JinB8 transfectants were pretreated with PMA for 24 hours (2 ng/mL) before killing. CD47-induced cell death was calculated as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” (C) Light microscopy of PMA-activated Jurkat cells transfected with CD8-C2 construct. Untreated cells (i), cells cultured for 18 hours with soluble (ii), immobilized CD47 mAb (iii) or immobilized antimouse CD8α mAb (iv).

Previous studies on the CD47 molecule have demonstrated that IgV and MMS domains are generally necessary for CD47-induced cell spreading and costimulation.26,27,46 47 We therefore explored the requirement of the IgV or the MMS domains in CD47-induced cell death. To this end, we used 2 constructs: IAP/CD7, made of the CD47 IgV domain fused to the membrane and cytoplasmic domains of human CD7, and CD8MC2, made of the extracellular domain of mouse CD8α fused to the MMS and cytoplasmic tail of CD47 form 2 (Figure 4A). The following data indicate that neither CD47 IgV nor MMS domain alone was sufficient to mediate cell death signaling. Engagement of CD8MC2 chimera by immobilized anti-CD8 on either U937 or PMA-activated Jurkat transfectants or ligation of IAP/CD7 chimera by CD47 mAb on JinB8 transfectants did not trigger cell death (0%, n = 4 and 2%, n = 6, respectively). Thus, we conclude that CD47-induced cell death signaling requires both the IgV and MMS domains of the molecule, whereas the cytoplasmic tail is not required.

PS externalization in CD47-induced cell death is down-regulated by K+ efflux impairment and antimycin A treatment

Cell shrinkage, PS externalization, and drop in ΔΨm are major hallmarks of apoptosis. Cell volume loss has been demonstrated to result in potassium [K+] and sodium [Na+] efflux.38,48 Furthermore, K+ efflux and drop in ΔΨm are tightly coupled.49,50 To examine whether CD47-induced cell death was dependent on K+ efflux, we performed cell cultures in RPMI medium in which Na+/K+ concentrations had been inverted, resulting in K+ efflux impairment by osmotic forces.38 Under these conditions, CD47-induced PS externalization, together with cell shrinkage, were delayed following CD47 ligation in B-CLL cells and the U937 cell line when compared to that observed in cultures with medium reconstituted with a normal [Na+]/[K+] ratio (Figure5A and not shown). ΔΨm was also slightly decreased (V.M. and M.S., unpublished observations, May 2000).

Down-regulation of CD47-induced PS exposure by K+ efflux or antimycin A treatment: lack of effect of PKC inhibitor rottlerin.

Freshly isolated B-CLL cells and the U937 cell line were cultured with or without immobilized CD47 mAbs. (A) Cultures were performed in RPMI medium containing normal [Na+] or inverted [Na+]/[K+] ratios [K+]. Shown are percent of viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−). (B-C) Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of immobilized CD47 mAbs with or without antimycin A (30 μM) or increasing concentrations of rottlerin. Shown is the percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC cells); one representative experiment of 4 is shown.

Down-regulation of CD47-induced PS exposure by K+ efflux or antimycin A treatment: lack of effect of PKC inhibitor rottlerin.

Freshly isolated B-CLL cells and the U937 cell line were cultured with or without immobilized CD47 mAbs. (A) Cultures were performed in RPMI medium containing normal [Na+] or inverted [Na+]/[K+] ratios [K+]. Shown are percent of viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−). (B-C) Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of immobilized CD47 mAbs with or without antimycin A (30 μM) or increasing concentrations of rottlerin. Shown is the percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC cells); one representative experiment of 4 is shown.

Classically, PS exposure is dependent on caspase activation, and PS externalization can be blocked by antimycin A, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. As depicted in Figure 5B, antimycin A totally prevented PS exposure in CD47-treated cells, whereas it had no effect on decreased ΔΨm, strongly suggesting that these 2 events are uncoupled. Mechanisms involved in PS exposure are rather complex and not entirely understood. For example, in some models of apoptosis, long-term PS exposure has been shown to be the net result of increased scramblase (which has no selectivity for the direction of bilayer lipids movement) and decreased translocase activity (which selectively transports PS from the outer leaflet back to the inner leaflet). Protein kinase C (PKC)δ reportedly activated scramblase in apoptotic cells.51 We observed CD47-induced cell death in the presence of rottlerin, an inhibitor of new PKC family isoforms, notably of PKCδ (Figure 5C). These data exclude a role for PKCδ without ruling out the involvement of other PKC isoforms. Indeed, immobilized CD47 mAb activated PKCθ in T cells.27

These results support the hypothesis that CD47-induced cell death involves cell volume dysregulation, which is partly associated with K+ efflux, and that PS exposure is intimately linked to cell shrinkage but may be uncoupled from decreased ΔΨm and is independent of PKCδ activation.

CD47-induced cell death involves cytoskeleton rearrangement

It was previously reported that T- and B-cell lines46,52 as well as B-CLL cells13 attach to and spread on CD47 mAb-coated surfaces, suggesting that CD47 ligation induces a change in cytoskeleton organization. Moreover, immobilized CD47 mAb reportedly induced F-actin polymerization in activated T cells.27 To assess the role of cytoskeleton in CD47-triggered cell death, we examined the effect of cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization. Treatment with cytochalasin D prevented both PS exposure and ΔΨm loss in CD47 mAb–treated U937 and B-CLL cells (Figure 6A). These data confirm and extend a previous report showing that cytochalasin D inhibited CD47-induced caspase-independent cell death in normal TCR-activated T cells.14

Link between CD47-induced PS exposure and cytoskeleton rearrangement.

(A) Freshly isolated B-CLL cells or the U937 cell line were cultured overnight in the presence or absence of immobilized CD47 mAbs with or without cytochalasin D (Cyto D; 20 μM). Shown is percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC6lowcells); one representative experiment of 4 is shown. (B-D) PBMCs were isolated from 4 WAS patients and cultured in the absence (Bi) or presence (Bii) of immobilized CD47 mAb. Annexin-V/PI and DiOC6 staining (patient no. 3) (B) and CD47 expression of PBMCs from patient no. 3 (B6H12) (C); percent viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−) in PBMCs of 4 WAS patients and 1 control donor (D).

Link between CD47-induced PS exposure and cytoskeleton rearrangement.

(A) Freshly isolated B-CLL cells or the U937 cell line were cultured overnight in the presence or absence of immobilized CD47 mAbs with or without cytochalasin D (Cyto D; 20 μM). Shown is percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC6lowcells); one representative experiment of 4 is shown. (B-D) PBMCs were isolated from 4 WAS patients and cultured in the absence (Bi) or presence (Bii) of immobilized CD47 mAb. Annexin-V/PI and DiOC6 staining (patient no. 3) (B) and CD47 expression of PBMCs from patient no. 3 (B6H12) (C); percent viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−) in PBMCs of 4 WAS patients and 1 control donor (D).

The motility of B-cell lines plated on CD47 mAb–coated surfaces requires the GTPase Cdc42.52 Since the Cdc42/WASP pathway is defective in cells from patients with WAS, we examined the effect of CD47 ligation in PBMCs isolated from WAS patients. We tested PBMCs of 4 characterized patients carrying WAS gene mutations, all leading to impaired WASP expression. As depicted in Figure 6B,D, we consistently failed to observe PS exposure and ΔΨm loss following CD47 ligation in WAS PBMCs, strongly suggesting a role for the Cdc42/WASP signaling pathway in CD47-induced cell death.

Taken together, these data indicate that cytoskeleton rearrangement is a key event in the triggering of CD47-mediated PS externalization and ΔΨm loss.

Discussion

The present findings indicate that caspase-independent cell death induced by CD47 stimulation is sufficient to trigger a signal for phagocytosis in human DCs. The CD47-induced cell death involves PS exposure, disruption of mitochondrial function, and cytoskeleton rearrangement possibly linked to the Cdc42/WAS protein (WASP) signaling pathway. This observation challenges the classical concept that both caspase activation and PS exposure triggered by caspases are prerequisites for phagocytosis. Elimination of dead cells in the absence of caspase activation and nuclear degradation has been previously reported. For instance, constitutive but caspase-independent death of platelets, anucleated blood cells, leads to PS exposure and clearance by phagocytes.53 However, caspase-independent or -dependent PS exposure appears to be a critical event to allow engulfment of dead cells by phagocytic cells.54 A PS receptor was recently identified and cloned, and anti–PS receptor mAb inhibited elimination of apoptotic cells.55Blocking PS exposure without suppression of mitochondrial collapse and nuclear degradation prevented phagocytosis.56 But cells dying by delayed necrosis upon exposure to staurosporine and z-VAD-fmK were eliminated without PS externalization, underlying the potential role of other candidates for recognition and elimination of dead cells by APCs.57

Caspases play a central role in the execution of cell death. These enzymes are recruited and activated by either receptors of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family or by apoptogenic molecules released from the intermembrane space of the mitochondria.58 Nevertheless, apart from CD47, stimulation of several surface antigens resulted in the activation of caspase-independent PS exposure in human cells. This includes CD2, MHC class I, and MHC class II.11,16,17 In contrast to CD47, ligation of these antigens may induce either caspase-dependent or -independent death according to the epitope triggered. So far, CD47 ligation by soluble, immobilized, or cross-linked mAbs recognizing at least 3 different epitopes exclusively induced caspase-independent cell death (Mateo et al,13 Pettersen et al,14 and data not shown).

During apoptosis, mitochondrial changes result in the dissipation of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm). The loss of ΔΨm is generally mediated by opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition (PT) pores and as a consequence, the release of apoptogenic molecules such as AIF and cyt c59with subsequent caspase-independent or -dependent nuclear degradation. The engagement of CD47 results in cell shrinkage and ΔΨm loss, and this occurs in the absence of caspase activation and DNA degradation likely excluding the involvement of AIF and cyt c. Indeed, AIF release ultimately leads to caspase-independent DNA degradation60 and cyt c to caspase activation.61 However, inactivation of cyt c by at least HSP27 binding has been shown to prevent apoptosome formation and caspase activation.62 We therefore postulate that either cyt c is inactivated and translocation of AIF to the nucleus impaired or that there is no release of apoptogenic molecules during CD47 stimulation. Our unpublished observations indicate that inhibitors of permeability transition pore complex (PTPC) opening failed to prevent CD47-induced cell death. They include cyclosporin A in combination with aristolochic acid (which acts on cyclophilin D and PLA2, respectively), bongkrekic acid (inhibitor of adenine nucleotide transfer [ANT]), and Ca++chelators.59 In support of the latter hypothesis, B-cell receptor (BCR)–mediated apoptosis of immature B-cell line resulted in ΔΨm loss but did not induce cyt c release and caspase activation.63 Interestingly, cyt crelease may occur in the absence of ΔΨm loss by a direct effect of the proapoptotic molecule Bid/Bik.64

We also provide evidence that CD47-induced PS exposure may be dissociated from ΔΨm loss but is intimately linked to cell shrinkage. Cell volume decrease during apoptosis is an active mechanism that was shown to be dependent on K+ channels (reviewed in Gomez-Angelats et al48 and Yu and Choi65). Maeno et al66 observed apoptotic volume decrease in the presence of zVAD-fmk, suggesting that K+ efflux is caspase independent. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that this phenomenon may occur upstream of caspase activation. In the present study, mitochondrial inhibitors such as antimycin A inhibited CD47-induced PS exposure but not dissipation of ΔΨm. Similar observations were made by Zhuang et al in ectoposide orN-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)–induced apoptosis of THP-1 monocyte cell line.56 Of interest, antimycin A alone induced ΔΨm in B-CLL and U937 cell lines. In that respect, antimycin A mimicked BH3 cell-death domain and induced mitochondrial swelling and ΔΨm loss.67 Taken together, these results strongly suggest that factors other than cyt c. released by the mitochondria and caspases may directly or indirectly affect PS exposure in CD47-induced cell death.

As described for CD47-mediated cell spreading and costimulation in T-cell lines, both extracellular and multispan transmembrane domains of CD47 molecule were required to induce killing. The short cytoplasmic domain was dispensable. In T cells, ∼ 65% of the CD47 molecule is localized in membrane rafts, where it regulates TCR-dependent and -independent T-cell activation. Immobilized CD47 mAb reportedly controlled the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins and triggered F-actin polymerization and PKCθ translocation.27However, CD47 mAb–induced killing was observed in the presence of G protein inhibitor (that is, pertussis toxin) (V.M. and M.S., data not shown) or new PKC family (δ, ε, η, θ, and μ) inhibitor (ie, rottlerin). PKCθ expression was low in B-cell lines, largely excluding its involvement in CD47-induced cell death.

Yoshida et al previously reported that CD47 regulated human B-cell motility through Cdc42.52 We observed that engagement of CD47 induced spreading of B-CLL cells. Cdc42 belongs to the small Rho GTPases family, which includes Rho and Rac, known to regulate formation of actin structures in many cell types.68 Among others, Cdc42 appears to have a unique role in actin remodeling during T-cell activation and endocytosis of immature DCs. WASP, uniquely expressed on hematopoietic cells,69 is the specific effector of Cdc42. WASP binds Cdc42 and controls actin polymerization by distinct domains.70 WAS-immunodeficiency syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in cytoskeletal function, resulting in abnormal chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and T-cell responses.69

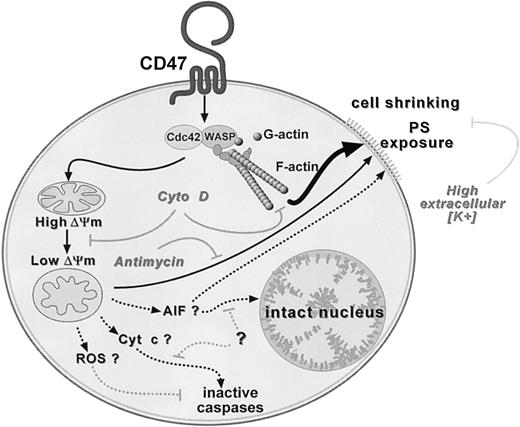

Two observations strongly suggest a direct role of cytoskeleton rearrangement in CD47-induced cell death: (1) inhibition of both PS exposure and ΔΨm loss by cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, and (2) absence of CD47-induced death in PBMCs of WAS patients. As depicted in a schematic model in Figure7, we propose that CD47 ligation induces killing by 2 nonmutually exclusive pathways. The initial and common event would be the triggering of actin polymerization, perhaps via Cdc42/WASP pathway. This will lead to either mitochondrial changes including matrix swelling and ΔΨm loss, followed by PS exposure (pathway #1) and/or to a direct effect on PS externalization, bypassing mitochondria (pathway #2).

Hypothetical model for CD47-induced PS exposure.

Two nonmutually exclusive pathways leading to PS exposure and initiated by a common triggering event: Cdc42/WASP signaling pathway and F-actin polymerization. Inhibition by cytochalasin D (Ctyo D). Pathway no. 1 (thin arrow): loss in ΔΨm followed by PS externalization. Antimycin A inhibits PS but not ΔΨm loss. Pathway no. 2 (thick arrow): bypass of mitochondria and direct induction of PS externalization. Elevated extracellular K+ slows down PS exposure. Absence of caspase activation and nuclear degradation in CD47-induced cell death. Dotted arrows indicate hypothetical inhibitory pathways. ROS indicates reactive oxygen species; AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; Cyt c, cytochrome c.

Hypothetical model for CD47-induced PS exposure.

Two nonmutually exclusive pathways leading to PS exposure and initiated by a common triggering event: Cdc42/WASP signaling pathway and F-actin polymerization. Inhibition by cytochalasin D (Ctyo D). Pathway no. 1 (thin arrow): loss in ΔΨm followed by PS externalization. Antimycin A inhibits PS but not ΔΨm loss. Pathway no. 2 (thick arrow): bypass of mitochondria and direct induction of PS externalization. Elevated extracellular K+ slows down PS exposure. Absence of caspase activation and nuclear degradation in CD47-induced cell death. Dotted arrows indicate hypothetical inhibitory pathways. ROS indicates reactive oxygen species; AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; Cyt c, cytochrome c.

When blood cell susceptibility was examined, immature DCs, activated T cells, and CD34+ precursors appeared to be much less sensitive and virtually resistant to CD47-induced killing. Similar differences in APC susceptibility have been reported in HLA-DR–induced caspase-independent cell death.71 Pettersen et al14 reported that CD47 mAb preferentially induces killing in normal activated but not resting T cells, and this was inhibited by cytochalasin D. We failed to induce cell death in anti-CD3–activated T cells. The use of different mAbs in the 2 studies and the regulation of CD47 conformation during T-cell activation (M.S. and V.M., unpublished data, January 2000) may provide one explanation for this discrepancy.

The role of CD47-induced killing in the regulation of immune response remains poorly understood. One may envision that it at least participates in the maintenance of homeostasis. Indeed, apoptosis is a self-destruction process which, in contrast to necrosis, does not lead to inflammatory response and may be involved in the induction of tolerance. Thrombospondin, the natural ligand of CD47, establishes a molecular bridge between apoptotic cells and APCs, facilitating phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.72 We reported that TSP, like CD47 mAb, induced caspase-independent cell death via CD47 binding but also acted on APCs to down-regulate the production of the proinflammatory molecule IL-12 and prevent DC maturation.23 It is important to mention that additional mechanisms inhibit inflammation during phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. They include induction of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β production by apoptotic cells themselves73 and by APCs upon their interaction with apoptotic cells.74 Also, TSP was found to be the main activator of TGFβ, and, reciprocally, TGFβ induces TSP production.75 76

CD47 was recently reported to be a marker of self on murine cells that prevented clearance of intact red blood and lymphoid cells by CD47+ APCs through the engagement of its counterstructure SIRP-α, selectively expressed on APCs.77 Also, CD47/SIRP-α interactions negatively regulated APC functions.28 However, apoptotic cells (highly expressing CD4778) are known to be efficiently cleared by APCs, and this is not inhibited by CD47 mAb.23 79 Whether CD47 expressed on apoptotic cells has a particular conformation in order not to deliver a negative signal for phagocytosis to APCs via SIRP-α or, conversely, whether SIRP-α/CD47 interactions can induce cell death remain open questions.

Taken together, we propose that TSP-induced/enhanced PS exposure via CD47 on lymphoid cells, followed by their elimination by professional phagocytes, represent a process that continuously takes place in peripheral tissues to ensure the maintenance of tissue and host homeostasis. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory activity of TSP, combined with its ability to facilitate the clearance of apoptotic cells, may further contribute to homeostasis and induction of tolerance by avoiding inappropriate immune response to self-antigens.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 14, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0217.

Supported by grants from Fondation Medic and the Leukemia Research Foundation of Canada.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marika Sarfati, Centre de Recherche du CHUM, Hôpital Notre-Dame, Laboratoire d'Immunorégulation (M4211-K), 1560 Sherbrooke St East, Montréal, QC H2L 4M1, Canada; e-mail: m.sarfati@umontreal.ca.

![Fig. 5. Down-regulation of CD47-induced PS exposure by K+ efflux or antimycin A treatment: lack of effect of PKC inhibitor rottlerin. / Freshly isolated B-CLL cells and the U937 cell line were cultured with or without immobilized CD47 mAbs. (A) Cultures were performed in RPMI medium containing normal [Na+] or inverted [Na+]/[K+] ratios [K+]. Shown are percent of viable cells (annexin-V−/PI−). (B-C) Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of immobilized CD47 mAbs with or without antimycin A (30 μM) or increasing concentrations of rottlerin. Shown is the percent of dead cells (annexin-V+ or DiOC6low cells); one representative experiment of 4 is shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/8/10.1182_blood-2001-12-0217/4/m_h82023277005.jpeg?Expires=1771015399&Signature=k0yhMHq7kXgasK90gihraECd9w5RD6ddcirSftV-gip0Ry5Gvqofqi0HV5h9LEkumS7pQ26dsyNKhVlZJ0tfa-Q2bbrwIakfMQXJQcPuUHTEWbiTwlkaHjPF0KN2Lx817UmjiV9T1e2LoVQxRXH8-eS8VFFFhqBJEKCig-0I3H6lPJASbNAs8muBAofN59fVcrxIVDIs0ZGHHMV1jknn4pgHtr1z5NtS5EwsXsY0n6e9zksYRF~BZup7ReqtqmnMCqPdVqgdhc3FQv6tHCjhp1DTn3I9brlvLG8fCHEbbpjnIbxSyI1mwzkCn~H~Px24P3VN0spS6Ec4BX0RcUK~7g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal