Omega-3 fatty acids, which are abundant in fish oil, improve the prognosis of several chronic inflammatory diseases although the mechanism for such effects remains unclear. These fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), are highly polyunsaturated and readily undergo oxidation. We show that oxidized, but not native unoxidized, EPA significantly inhibited human neutrophil and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells in vitro by inhibiting endothelial adhesion receptor expression. In transcriptional coactivation assays, oxidized EPA potently activated the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a member of the nuclear receptor family. In vivo, oxidized, but not native, EPA markedly reduced leukocyte rolling and adhesion to venular endothelium of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–treated mice. This occurred via a PPARα-dependent mechanism because oxidized EPA had no such effect in LPS-treated PPARα-deficient mice. Therefore, the beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids may be explained by a PPARα-mediated anti-inflammatory effect of oxidized EPA.

Introduction

Consumption of omega-3 fatty acids in fish oil has been reported to improve the prognosis of several chronic inflammatory diseases characterized by leukocyte accumulation, including atherosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.1-4 Fish oil is also recommended for treatment of IgA nephropathy, the most common form of primary renal disease worldwide.5,6 Several studies suggest that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation may reduce the inflammatory response by attenuating leukocyte adhesion to the vessel wall.7-9 However, the primary mechanism for the anti-inflammatory effects of fish oil remains unclear.10

Omega-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are highly polyunsaturated and readily undergo oxidation.11 This suggests the possibility that oxidized omega-3 fatty acids may be an important component of the observed anti-inflammatory effects of fish oil. Indeed, Sethi and colleagues showed that oxidized EPA and DHA are more potent than native fatty acids in reducing RNA levels of leukocyte adhesion receptors and the adhesion of leukocyte cell lines to endothelial cells in vitro.12 Polyunsaturated fatty acids may exert their effects in cells by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). PPARs are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate genes important in cell differentiation and various metabolic processes. Known PPAR isoforms include PPARγ, important in lipoprotein metabolism, adipogenesis, and insulin sensitivity; PPARα, implicated in fatty acid metabolism; and PPARδ, about which the least is known.13,14 Synthetic PPARα ligands such as fibrates (eg, fenofibric acid) are used in patients to lower triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Synthetic PPARγ ligands such as thiazolidinediones (eg, rosiglitazone) are insulin-sensitizing drugs used in the treatment of diabetes. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and eicosanoids are known natural ligands of PPARα, γ, and δ although they are required in relatively high concentrations (approximately 100 μM) for PPAR activation and are not selective for PPAR subtypes.15,16On the other hand, derivatives of fatty acids further activate PPAR and can exhibit selectivity for PPARα or PPARγ in in vitro assays. For example, a cyclo-oxygenase product of arachidonic acid, 15d-delta12,14-PGJ2, is a selective PPARγ ligand, whereas its lipoxygenase product 8(S)hydroxy-(5Z,9E, 11Z,14Z)-eicosatetraenoic acid (HETE) is a selective PPARα agonist.17 Recently, both PPARα and PPARγ were identified in endothelial cells.14 Synthetic PPARα agonists decreased the transcription of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and the adhesion of HL60 cells to cytokine-activated endothelial cells.18 Other studies suggest that PPARγ agonists may also inhibit cytokine-induced VCAM-1 expression,19,20although such effects were not seen in vivo.21

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of oxidized versus native omega-3 fatty acid, EPA, on the interaction of human blood leukocytes with endothelial cells in vitro, to examine if PPARs are activated by oxidized EPA and are therefore potential targets of oxidized EPA-mediated effects, and to determine the relevance of the paradigm established in vitro, in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated inflammation in vivo. Our results show that oxidized EPA inhibits the adhesion of freshly isolated human peripheral blood neutrophils and monocytes to an activated endothelial cell monolayer under static and physiologic flow conditions, by reducing the surface expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors. We demonstrate that oxidized EPA potently activates PPARα to levels seen with fenofibric acid, a well-characterized synthetic PPARα agonist. Finally, we demonstrate that oxidized EPA, but not native EPA, significantly decreases leukocyte adhesion to the inflamed endothelium in vivo and that activation of PPARα is essential for this effect.

Materials and methods

Preparation of fatty acids

The EPA was purchased specifically from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). It was relatively unoxidized as assessed by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA)–reactive substances (TBARs) assay using malondialdhyde (MDA) as a standard; this assay is a measure of fatty acid oxidation.22 EPA was dissolved in 100% ethanol and stored as a 100-mM stock under nitrogen to ensure minimal oxidation. Then, 3.3 mM EPA was made up in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 5 μM cupric sulfate and 300 μM ascorbic acid were sequentially added and are referred to as oxidizing reagents. The sample was incubated at 37°C for 12 hours. Extensive oxidation was observed as assessed by TBARs. For treatment of cells, oxidized EPA or native EPA was diluted in media containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) to final concentrations between 10 and 100 μM. The vehicle control for oxidized EPA was media containing PBS plus oxidizing agents.

Adhesion assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) monolayers in 96-well plates were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle control, native EPA (100 μM), or oxidized EPA (10, 50, 100 μM) in standard growth medium. After 1 hour, the HUVECs were washed, the medium was replaced, and the cells were stimulated with LPS (50 ng/mL; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO), human interleukin 1β (IL-1β; 10 U/mL), or human tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α; 10 ng/mL) for 5 hours. Leukocytes were fluorescently labeled with the fluorescent probe bis-carboxyethyl-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-am; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), added to wells (6 × 104/well), and incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C. The wells were washed and filled with media; the plates were sealed, inverted, and spun at 100g for 5 minutes to remove nonadherent leukocytes. Adherence of labeled leukocytes was determined in a plate reader. Control studies indicated that fluorescence was a linear function of leukocytes in the range of 3000 to 60 000 cells/microplate well. Based on the standard curve obtained, the results are reported as the number of neutrophils or monocytes adherent per well of endothelial cells.

Parallel plate flow assay

Confluent HUVECs plated on a coverslip were treated as described for the adhesion assay. The HUVECs were placed in a parallel plate flow chamber under defined laminar flow, and neutrophils (106/mL) were applied at fluid shear stress varying from 2 to 0.25 dynes/cm2 as previously described.23Leukocyte behavior was recorded on videotape and analyzed. The number of rolling and adherent neutrophils were determined in a minimum of 5 high power fields (× 20 magnification; 20 s/field) at each shear stress and averaged.

Fluorescent immunoassay

The HUVEC monolayers in 96-well plates were treated as indicated above. The cells were washed with RPMI with 1% FBS and placed on ice. Primary monoclonal antibodies to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), E-selectin, VCAM-1, endoglin, and HLA class I were diluted in RPMI-1% FBS and added to each well for 1 hour on ice. The cells were washed 3 times with RPMI-1% FBS and fluorescein isothiocyanate F(ab)2 goat antimouse IgG was added to each well. After incubation for 1 hour on ice the cells were washed twice with Dulbecco PBS containing 20% FBS (to quench nonspecific binding) and twice with DPBS. The cells were solubilized with lysis buffer and the fluorescence was read in a fluorescence microplate reader.

Transcriptional coactivation assay

Transient transfection was carried out in primary bovine aortic endothelial cells using the Superfect method (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, cells were plated in 24-well plates at 2.3 × 104 cells/well in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 5% FCS. After 16 hours of growth, cells were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) and transfected with medium containing Superfect/DNA complexes (ratio 5.5:1) for 4 hours. Reporter construct pUASx4-TK-luc and chimeric human PPARα–ligand-binding domain (LBD) constructs have been described previously.24 PCMX-β-galactosidase expression vector was used as a transfection control. Transfected cells were left overnight in medium, followed by treatment with the indicated compounds for 10 hours. Luciferase activity was assayed in a lysis buffer (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) using a reporter assay system (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Activity of β-galactosidase was monitored at 540 nm using chlorophenyl red β-d galactopyranoside (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) as a substrate. Rosiglitazone and fenofibric acid were used at concentrations of 1 μM and 100 μM, respectively.

Intravital microscopy of mesenteric venules

Four-week-old 129SV wild-type and PPARα−/−mice25 (inbred 129SV strain, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected intraperitoneally with 500 μL PBS with oxidation reagents (vehicle), 500 μL 3.3 mM oxidized EPA (to achieve approximately 275 μM concentration in the blood assuming 3 mL blood volume and 3 mL extravascular fluid and equal distribution between these 2 compartments), or with 500 μL 3.3 mM native unoxidized EPA in PBS. One hour later the mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of LPS (1 μg in 100 μL PBS). Five hours later mice were anesthetized and the mesentery was gently exteriorized and prepared for intravital microscopy as previously described.26 Rolling leukocytes were quantitated in venules of 25 to 35 μm in diameter by counting the number of cells passing a given plane perpendicular to the vessel axis in 3 minutes, and the number per minute was calculated. Centerline erythrocyte velocity (Vrbc) was measured using an optical Doppler velocimeter and venular shear rate was calculated as previously described.26 A minimum of 3 venules was studied per animal. Leukocytes adherent to the vessel wall were counted per square millimeter of venular area at the end of every 3 minutes. At the end of the experimental procedure, peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus and total leukocyte counts were determined.26 Experimental procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as average ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by the unpaired Student ttest.

Results

Generation of oxidized EPA

Unoxidized EPA was diluted in media and subjected to oxidation by the addition of cupric sulfate and ascorbic acid as described in “Materials and methods.” Gas chromatography mass spectrometry of the samples revealed a single peak in the unoxidized EPA sample, which was consistent with native EPA, whereas oxidized EPA had less than 1% of the native EPA and a number of additional peaks that likely correspond to EPA oxidation products (data not shown). The extent of EPA oxidation in unoxidized or oxidized EPA is quantitated by measuring the amount of aldehydes present as previously reported.12The aldehyde content of 100 μM unoxidized EPA was less than 0.02 μM MDA. Oxidized EPA was 1.78μM MDA in 100 μM EPA,12which is in the range seen in plasma of humans (1.52-3.45 μM MDA) and animals (1.93 μM MDA) fed fish oil diets.27-31Unoxidized EPA diluted in PBS to 100 μM and exposed to air (but not additional oxidizing agents) for 2 days at 37°C also showed significant oxidation (1.44 μM MDA), which highlights the propensity for this highly polyunsaturated fatty acid to oxidize.

Oxidized EPA inhibits neutrophil and monocyte interaction with the endothelium under static adhesion and fluid shear stress conditions

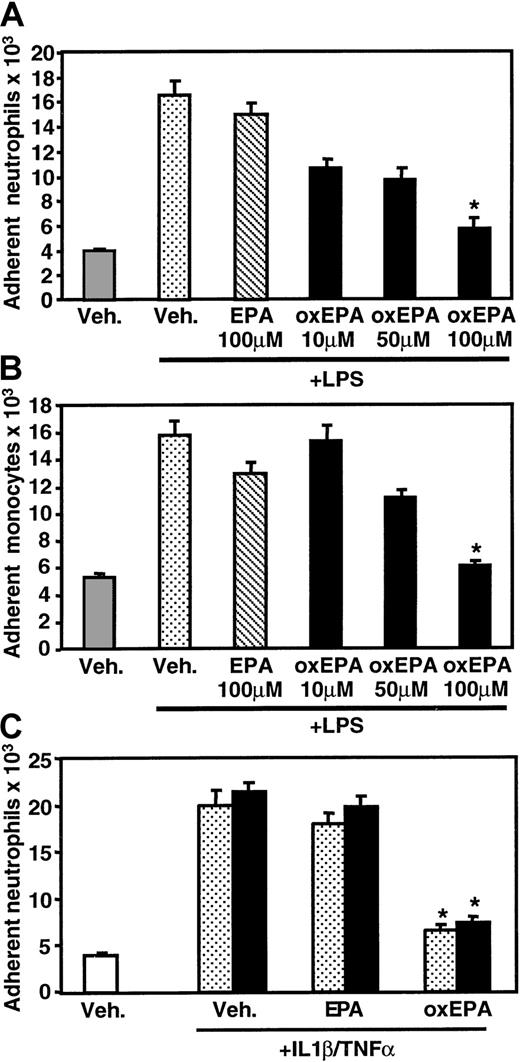

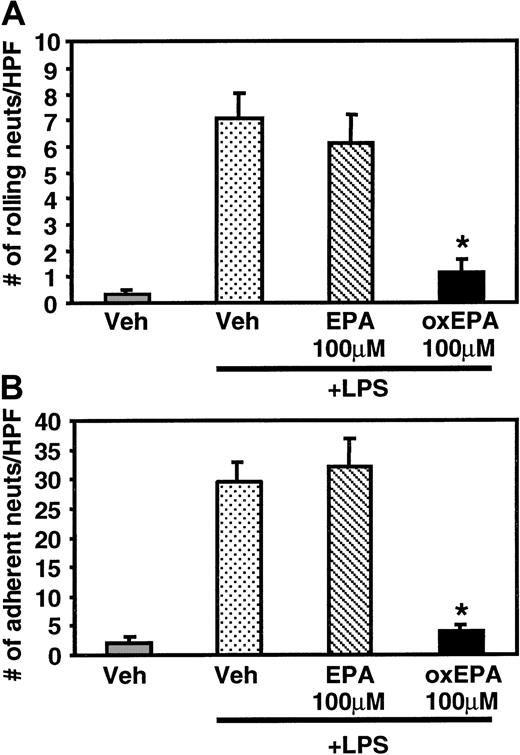

In static adhesion assays, pretreatment of HUVECs with oxidized EPA for 1 hour prior to LPS stimulation significantly inhibited the adhesion of peripheral blood human neutrophils and monocytes, whereas incubation with unoxidized, native EPA had little effect (Figure1A,B). The inhibition of LPS-induced adhesion was dose dependent; 100 μM oxidized EPA reduced leukocyte adhesion to levels close to those seen for unstimulated HUVECs. Oxidized EPA similarly inhibited neutrophil adhesion to HUVECs activated with TNF-α or IL-1β (Figure 1C). The effect of oxidized EPA on leukocyte rolling and firm adhesion to HUVECs under fluid shear stress conditions was assessed using a parallel plate flow chamber.23 HUVECs stimulated with LPS for 5 hours supported significant neutrophil rolling and adhesion under flow (0.5 dynes/cm2). Treatment of HUVECs with oxidized EPA for 1 hour prior to LPS stimulation significantly inhibited both rolling (Figure 2A) and adhesion (Figure 2B), whereas native EPA had no effect.

Effect of oxidized EPA on neutrophil and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells.

HUVECs were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle alone (Veh, PBS plus oxidizing reagents) or native (EPA) or oxidized EPA (oxEPA) at the indicated concentrations. HUVECs were then stimulated with LPS for 5 hours and assayed for human neutrophil (A) or monocyte (B) adhesion. (C) Endothelial cells were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle alone (Veh), 100 μM native (EPA), or oxidized EPA (oxEPA). HUVECs were then incubated with TNF-α (stippled bars) or IL-1β (solid bars) and assayed for neutrophil adhesion. Results are expressed as number of leukocytes attached per well of endothelial cells (± SEM). *P < .00001 compared with EPA + LPS or IL-1β or TNFα, and Veh + LPS or IL-1 or TNF, n = 3.

Effect of oxidized EPA on neutrophil and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells.

HUVECs were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle alone (Veh, PBS plus oxidizing reagents) or native (EPA) or oxidized EPA (oxEPA) at the indicated concentrations. HUVECs were then stimulated with LPS for 5 hours and assayed for human neutrophil (A) or monocyte (B) adhesion. (C) Endothelial cells were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle alone (Veh), 100 μM native (EPA), or oxidized EPA (oxEPA). HUVECs were then incubated with TNF-α (stippled bars) or IL-1β (solid bars) and assayed for neutrophil adhesion. Results are expressed as number of leukocytes attached per well of endothelial cells (± SEM). *P < .00001 compared with EPA + LPS or IL-1β or TNFα, and Veh + LPS or IL-1 or TNF, n = 3.

Effect of oxidized EPA on rolling and adhesion of neutrophils under laminar flow.

HUVECs were treated with vehicle alone or native or oxidized EPA (100 μM) for 1 hour prior to stimulation with LPS for 5 hours. The HUVEC-containing coverslip was placed in a parallel plate flow chamber and resting neutrophils (106/mL) were infused at 0.5 dynes/cm2 wall shear stress. The number of rolling (A) and adherent neutrophils (B) were determined and averaged ± SEM. *P < .00007 compared with Veh + LPS, n = 3.

Effect of oxidized EPA on rolling and adhesion of neutrophils under laminar flow.

HUVECs were treated with vehicle alone or native or oxidized EPA (100 μM) for 1 hour prior to stimulation with LPS for 5 hours. The HUVEC-containing coverslip was placed in a parallel plate flow chamber and resting neutrophils (106/mL) were infused at 0.5 dynes/cm2 wall shear stress. The number of rolling (A) and adherent neutrophils (B) were determined and averaged ± SEM. *P < .00007 compared with Veh + LPS, n = 3.

Oxidized EPA inhibits cytokine-induced surface expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors on endothelial cells

Stimulation of HUVECs with LPS induces expression of adhesion receptors, such as E-selectin, and VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, which support leukocyte tethering and adhesion, respectively. Treatment with oxidized EPA resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in LPS-stimulated surface expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin, whereas treatment with native EPA did not (Table 1). Oxidized EPA had no significant effect on the expression of endoglin, a membrane protein that binds transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and HLA class I molecules, which are constitutively expressed.

Effect of oxidized EPA on expression of endothelial adhesion molecules

| . | Vehicle . | Vehicle + LPS . | EPA (100 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (10 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (50 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (100 μM) + LPS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-1 | 54 ± 5 | 272 ± 40 | 373 ± 36 | 265 ± 71 | 182 ± 50 | 61 ± 15* |

| VCAM-1 | 6 ± 4 | 211 ± 17 | 312 ± 38 | 198 ± 16 | 92 ± 26 | 29 ± 10† |

| E-selectin | ND | 248 ± 11 | 328 ± 75 | 191 ± 27 | 138 ± 36 | 53 ± 6† |

| Endoglin | 911 ± 65 | 736 ± 107 | 907 ± 45 | 781 ± 48 | 840 ± 38 | 743 ± 16 |

| HLA class I | 76 ± 7 | 79 ± 9 | 151 ± 16 | 67 ± 11 | 121 ± 31 | 109 ± 25 |

| . | Vehicle . | Vehicle + LPS . | EPA (100 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (10 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (50 μM) + LPS . | oxEPA (100 μM) + LPS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-1 | 54 ± 5 | 272 ± 40 | 373 ± 36 | 265 ± 71 | 182 ± 50 | 61 ± 15* |

| VCAM-1 | 6 ± 4 | 211 ± 17 | 312 ± 38 | 198 ± 16 | 92 ± 26 | 29 ± 10† |

| E-selectin | ND | 248 ± 11 | 328 ± 75 | 191 ± 27 | 138 ± 36 | 53 ± 6† |

| Endoglin | 911 ± 65 | 736 ± 107 | 907 ± 45 | 781 ± 48 | 840 ± 38 | 743 ± 16 |

| HLA class I | 76 ± 7 | 79 ± 9 | 151 ± 16 | 67 ± 11 | 121 ± 31 | 109 ± 25 |

HUVECs were pretreated for 1 hour with vehicle or native (EPA) or oxidized EPA (oxEPA) prior to stimulation with LPS for 5 hours. Surface expression of adhesion molecules was quantitated by fluorescent immunoassay using appropriate monoclonal antibodies.

ND indicates none detected.

P < .006 and

P< .002 compared to Vehicle + LPS (n = 3).

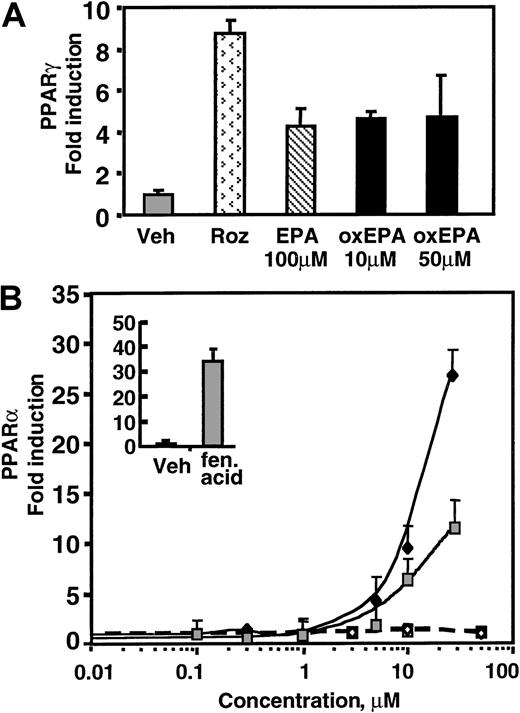

PPARα is activated in endothelial cells treated with oxidized EPA

We tested the possibility that oxidized EPA exerts its effects on endothelial cells through PPARs, hypothesizing that oxidation of EPA might increase its ability to activate PPARs as compared with native EPA. Using 2 hybrid transcriptional coactivation assays in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs),24 we found that both oxidized and native EPA can modestly activate PPARγ in a dose-independent manner (Figure 3A). In contrast, oxidized EPA potently activates PPARα in a dose-dependent manner from 5 to 30 μM and was approximately 2- to 2.5-fold stronger than native EPA at equivalent concentrations. Interestingly, the activity by oxidized EPA was at least as potent as fenofibric acid, a well-documented synthetic PPARα ligand (Figure 3B). The estimated half-maximal activity for oxidized EPA was 10 μM as compared with an EC50 of 30 μM for fenofibric acid.

Oxidized EPA activates PPARα-dependent transcription in BAECs.

PPARγ (A) or PPARα (B) activation was studied in BAECs using a yeast 2-hybrid Gal4 transfection assay for ligand-dependent activation. Cells were transfected with PPARα-LBD or PPARγ-LBD fused to the yeast transcription factor Gal4, or a control Gal4 plasmid. All cells were transfected with a yeast Gal4-binding site luciferase reporter construct. Activation events at the LBD were measured by increased luciferase activity. Gal4 alone is not activated in mammalian cells. Cells were treated with native EPA (EPA), oxidized EPA (oxEPA), or synthetic agonists of PPARα (fen acid: fenofibric acid, 100 μM) or PPARγ (roz: rosiglitazone, 1 μM). (A) Oxidized EPA led to a modest induction of PPARγ activation that was not dose dependent and was comparable to that observed with native EPA. (B) Dose-response curves for PPARα activation by native EPA (closed square) or oxidized EPA (closed diamond) are shown. Native and oxidized EPA treatment of cells transfected with the control Gal4 construct (open symbols) revealed no luciferase activity. Insert shows PPARα activation by fenofibric acid (fen acid; 100 μM), but not by vehicle (Veh) alone.

Oxidized EPA activates PPARα-dependent transcription in BAECs.

PPARγ (A) or PPARα (B) activation was studied in BAECs using a yeast 2-hybrid Gal4 transfection assay for ligand-dependent activation. Cells were transfected with PPARα-LBD or PPARγ-LBD fused to the yeast transcription factor Gal4, or a control Gal4 plasmid. All cells were transfected with a yeast Gal4-binding site luciferase reporter construct. Activation events at the LBD were measured by increased luciferase activity. Gal4 alone is not activated in mammalian cells. Cells were treated with native EPA (EPA), oxidized EPA (oxEPA), or synthetic agonists of PPARα (fen acid: fenofibric acid, 100 μM) or PPARγ (roz: rosiglitazone, 1 μM). (A) Oxidized EPA led to a modest induction of PPARγ activation that was not dose dependent and was comparable to that observed with native EPA. (B) Dose-response curves for PPARα activation by native EPA (closed square) or oxidized EPA (closed diamond) are shown. Native and oxidized EPA treatment of cells transfected with the control Gal4 construct (open symbols) revealed no luciferase activity. Insert shows PPARα activation by fenofibric acid (fen acid; 100 μM), but not by vehicle (Veh) alone.

Analysis of the effects of 100-μM doses of oxidized EPA on PPARγ and PPARα activation was not possible because unlike HUVECs, which were viable and responsive to cytokines at this dose of EPA, this concentration was toxic to the transfected BAECs likely because the transfection protocol or the expression of high levels of the LBD construct is somewhat toxic to the cells. Untransfected BAECs treated with 100 μM EPA remained viable. Thus, oxidized EPA potently activates PPARα in endothelial cells, which may explain the observed reduction in LPS-induced endothelial cell–receptor expression and leukocyte adhesion.

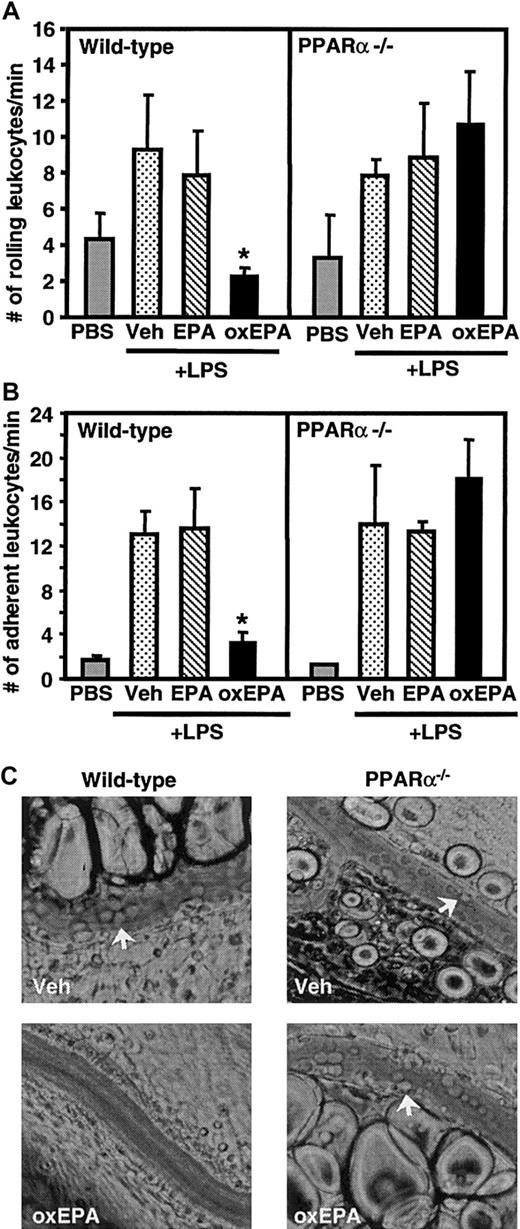

Oxidized EPA reduces leukocyte-endothelial interactions in vivo through activation of PPARα

Next, we determined if oxidized versus native EPA reduced leukocyte adhesion during inflammation in vivo and, if so, whether this occurred through a PPARα-dependent mechanism. Wild-type mice and mice deficient in PPARα were given an intraperitoneal injection of oxidized EPA, native EPA, or vehicle alone. After 1 hour, mice were injected intraperitoneally with LPS and 5 hours later underwent surgery and intravital microscopy of their mesenteric venules. In wild-type mice, LPS induced significant rolling and firm adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium (Figure 4). Similar levels of rolling and adhesion were observed in LPS-treated PPARα-deficient mice suggesting that PPARα does not play a role in LPS-induced leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium. LPS-injected wild-type mice pretreated with oxidized EPA, but not native EPA, had markedly reduced leukocyte rolling (75%) and adhesion (75%) to inflamed venular endothelium compared with LPS-injected wild-type mice pretreated with vehicle alone. Indeed, levels of rolling and adhesion in the LPS- and oxidized EPA-treated mice approached those seen in mice injected with vehicle alone (Figure 4). In contrast, LPS-treated PPARα-deficient mice pretreated with native or oxidized EPA demonstrated no decrease in leukocyte rolling and adhesion compared to wild-type or PPARα-deficient mice treated with LPS alone. Peripheral blood leukocyte counts and venular shear rates were comparable among all the different groups of mice (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that oxidized EPA inhibits leukocyte-endothelial interactions in vivo and that this occurs through a PPARα-dependent mechanism. The much stronger inhibitory effect of oxidized EPA versus native EPA on leukocyte adhesion in wild-type animals correlated well with its more potent activation of PPARα in endothelial cell cultures compared to native EPA (Figure 3B), a difference not seen for PPARγ activation (Figure 3A).

Effect of oxidized EPA on leukocyte rolling and adhesion in mesenteric venules in wild-type and PPARα-deficient mice.

Wild-type or PPARα-deficient mice (PPARα−/−) were given an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (Veh) alone, native EPA, or oxidized EPA (oxEPA) 1 hour prior to injection of LPS. Five hours later mice were anesthetized and mesenteric venules were observed. Rolling (A) and adherent leukocytes (B) were determined; n = 5 to 7 for each group of mice. *P < .03 compared with Veh + LPS (wild type) and oxidized EPA + LPS (PPARα−/−). (C) Representative photographs of leukocytes interacting with the vessel wall (arrows) in LPS-stimulated wild-type and PPARα−/− mice, after indicated treatments, are shown. Pictures were taken with a × 32 objective.

Effect of oxidized EPA on leukocyte rolling and adhesion in mesenteric venules in wild-type and PPARα-deficient mice.

Wild-type or PPARα-deficient mice (PPARα−/−) were given an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (Veh) alone, native EPA, or oxidized EPA (oxEPA) 1 hour prior to injection of LPS. Five hours later mice were anesthetized and mesenteric venules were observed. Rolling (A) and adherent leukocytes (B) were determined; n = 5 to 7 for each group of mice. *P < .03 compared with Veh + LPS (wild type) and oxidized EPA + LPS (PPARα−/−). (C) Representative photographs of leukocytes interacting with the vessel wall (arrows) in LPS-stimulated wild-type and PPARα−/− mice, after indicated treatments, are shown. Pictures were taken with a × 32 objective.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the beneficial effects of fish oil in chronic inflammatory diseases may be due to the oxidative modification of omega-3 fatty acids and its subsequent inhibition of leukocyte adhesion receptor expression and leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Oxidized EPA significantly inhibited LPS-induced leukocyte rolling and adhesion, which are processes mediated by leukocyte adhesion receptors of the selectin, integrin, and IgG superfamily, respectively.32 Native EPA had no effect on leukocyte recruitment in these models. Our proposed mechanism of omega-3 fatty acid actions may also contribute to the decreased atherosclerosis among populations with high intake of fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids.4 The amount of oxidized EPA that yielded a decrease in leukocyte-endothelial interactions in vivo was approximately 275 μM in circulation, which may be achieved in humans with fish oil supplementation (700 μM total EPA)28 or diets rich in salmon.33 34

Oxidation of EPA leads to the generation of a mixture of aldehydes, peroxides, and other oxidation products, which are probably responsible for the observed anti-inflammatory effect.12 Although the structure(s) of the specific aldehyde/peroxide(s) responsible for the anti-inflammatory activity is not currently known, these products are undoubtedly present in humans consuming these fatty acids for the following reasons. Highly polyunsaturated long-chained EPA is readily oxidized at room temperature even in the absence of exogenous oxidizing reagents. More importantly, in vivo, a large increase in tissue and plasma accumulation of fatty acid oxidation products is noted in subjects consuming fish oil7,27,28,35 even after addition of antioxidant supplements to the diet,27,28 which suggests extensive oxidation of omega-3 fatty acids such as EPA in vivo. During inflammation, increased oxidation of dietary omega-3 fatty acids may occur due to increased oxidative stress, and the expression of enzymes (eg, cyclo-oxygenase and lipoxygenase) capable of oxidizing polyunsaturated fatty acids. On the other hand, fish oil consumption does not lead to an increase in oxidation of plasma proteins,28 which is important because protein oxidation can contribute to the development of diseases such as atherosclerosis.36,37 Endothelial cells have also been identified as a source of the omega-3 fatty acid DHA,38 39which suggests the intriguing possibility that during inflammation, this fatty acid could be locally oxidized and serve as a potent natural anti-inflammatory mechanism for limiting the inflammatory response.

Our study provides a mechanism by which oxidized EPA inhibits leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Both oxidized and native EPA modestly activated PPARγ, but oxidized EPA potently activated PPARα in endothelial cells, and to a much greater extent than native EPA. Therefore, oxidation of the omega-3 fatty acid converts it into a stronger PPARα agonist. A recent study suggests that oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and not native LDL dose dependently activates PPARα in endothelial cells and that the oxidized phospholipid component is responsible for this effect.40In particular, oxidized metabolites of linoleic acid, 9- and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (9-HODE and 13-HODE) were potent PPARα ligands in endothelial cells.40 This, along with our study, suggests the possibility that oxidation of lipids may be one of the first steps involved in the generation of potent PPARα agonists in endothelial cells.

Although our studies indicate that native EPA activates PPARα about half as well as oxidized EPA, it had no effect on leukocyte-endothelial interactions in vitro or in vivo. The reasons for this may include the following. The cotranscriptional Gal4 LBD assay is a valuable method of isolating one aspect of ligand-PPAR interaction, namely, the affinity of LBD for ligand. However, this assay excludes other cellular events that have an impact on PPAR-induced cellular transcriptional responses such as phosphorylation of PPARα41 or PPARγ42 and the interaction between coactivators and corepressors with PPAR,43 all of which may differentially affect the ability of oxidized versus native EPA to modulate PPARα-mediated responses. For example, “nonproportional” responses have been seen for PPARγ and the putative ligand 15dPGJ2. This prostaglandin demonstrates much less PPARγ LBD affinity than the potent thiazolidinedione class of PPARγ agonists24 but has comparable biologic effects to these drugs in vitro.24,44 Another explanation for the differential results of oxidized EPA and EPA in the in vivo and transfection assays is that PPARα activation by EPA seen in the cotranscriptional assays might remain beneath a threshold required for seeing a functional effect. These limitations of the cotransfection assay emphasize the importance of obtaining evidence for PPARα activation in in vivo settings. Indeed, we show that oxidized EPA significantly inhibited leukocyte-endothelial interactions in the complex environment of LPS-induced inflammation in mice in vivo, a response that was absent in PPARα-deficient mice. Together, our data demonstrate that oxidized EPA can both activate a PPARα LBD in vitro and exert potent antileukocyte adhesive effects in vivo, which are entirely PPARα dependent. On the other hand, LPS treatment of wild-type and PPARα-deficient mice led to significant leukocyte rolling and adhesion, which was comparable in both genotypes, suggesting that PPARα does not play a role in LPS-induced leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. To our knowledge, ours is the first demonstration that a PPAR agonist (oxidized EPA) has potent inhibitory effects on neutrophil-endothelial interactions in vivo.18-20 Our studies also indicate that unlike the in vitro studies, which report that PPARα activation leads to the down-regulation of select leukocyte adhesion receptors (VCAM-1 but not ICAM-1 or E-selectin),18 in vivo, PPARα is responsible for down-regulating a spectrum of adhesion molecules required for leukocyte rolling and adhesion.

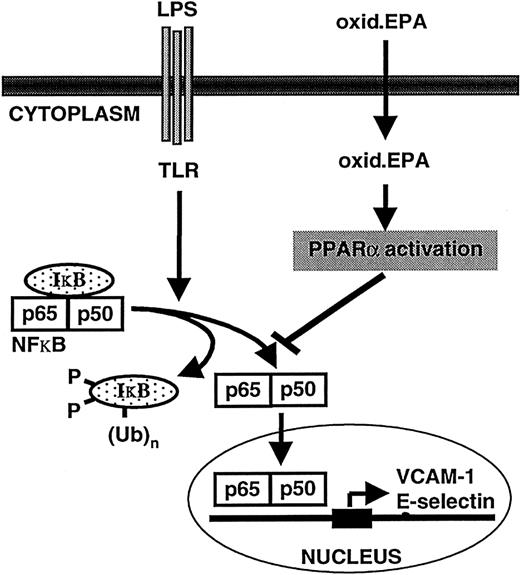

The down-regulatory effects of oxidized EPA-mediated PPARα activation is likely through an inhibition of LPS or cytokine-induced activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NFκB), which stimulates the transcription of several cytokine-inducible adhesion receptors including E-selectin and VCAM-1 (Figure5). Evidence for this comes from studies demonstrating that ligand-activated PPARα can inhibit NFκB activity through as yet partially unknown mechanisms (ie, direct interactions with the p65 subunit of NFκB or increased synthesis of the NFκB inhibitor, IκBα, have been implicated45-47), and previous data showing that oxidized EPA inhibits NFκB activation.12

Model of the mechanism of oxidized EPA-mediated down-regulation of LPS-induced endothelial-leukocyte interactions.

LPS interacts with the toll-like receptor (TLR) on endothelial cells, which ultimately leads to the phosphorylation of the NFκB inhibitor IκB, which is subsequently rapidly polyubiquinated and degraded by the proteosome. Released NFκB subunits (p65/p50) translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where they bind to NFκB response elements on target genes such as E-selectin and VCAM-1 and drive their transcription. Oxidized EPA is taken up by endothelial cells and activates PPARα. PPARα inhibits NFκB activation through partially understood mechanisms and thus abrogates target gene expression. Subsequent down-regulation of LPS-inducible leukocyte adhesion molecule expression at the cell surface leads to a reduction in leukocyte-endothelial interactions.

Model of the mechanism of oxidized EPA-mediated down-regulation of LPS-induced endothelial-leukocyte interactions.

LPS interacts with the toll-like receptor (TLR) on endothelial cells, which ultimately leads to the phosphorylation of the NFκB inhibitor IκB, which is subsequently rapidly polyubiquinated and degraded by the proteosome. Released NFκB subunits (p65/p50) translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where they bind to NFκB response elements on target genes such as E-selectin and VCAM-1 and drive their transcription. Oxidized EPA is taken up by endothelial cells and activates PPARα. PPARα inhibits NFκB activation through partially understood mechanisms and thus abrogates target gene expression. Subsequent down-regulation of LPS-inducible leukocyte adhesion molecule expression at the cell surface leads to a reduction in leukocyte-endothelial interactions.

The oxidized EPA-mediated activation of PPARα may be relevant in biologic responses beyond those that were studied here. It may accelerate fatty acid metabolism, which has implications for obesity, a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. In addition both fish oil and the PPARα agonist, fenofibrate, have cholesterol- and triglyceride-lowering effects, suggesting that oxidized EPA-induced PPARα activation may contribute to the lipid-lowering effect of fish oil, although a recent study in PPARα-deficient mice suggested PPARα and fish oil affect lipoprotein metabolism through different mechanisms.48

In summary, oxidized EPA is a potent inhibitor of leukocyte interactions with the endothelium compared to native EPA, both in vitro and in an in vivo context of inflammation. The effects of oxidized EPA are mediated through activation of PPARα, which is responsible for the down-regulation of leukocyte adhesion receptor expression required for leukocyte-endothelial interactions. We propose that oxidation of EPA and its activation of PPARα is one of the underlying mechanism for the beneficial effects of fish oil. Finally, given the potency of oxidized EPA in activating PPARα, and that its effects were comparable to those seen with the PPARα agonist, fenofibrate, our studies also suggest that oxidized omega-3 fatty acids may represent a class of naturally occurring, low-toxicity, PPARα agonists with potent anti-inflammatory properties.

The authors would like to thank Ms Kay Case for providing HUVECs, and Drs F. W. Luscinskas and Y. C. Lym (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA) for their help with the parallel plate flow chamber.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 17, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0316.

Supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute HL36028 (T.N.M.), HL53756 (D.D.W.), a research award from the American Diabetes Association (J.P.), the LeDucq Center for Cardiovascular Research (J.P.), and the American Heart Association (S.S). H.N. is a research fellow of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. O.Z. and H.N. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Tanya N. Mayadas, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 221 Longwood Ave, Room 404, Boston, MA 02130; e-mail: tmayadas@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal